#envisioned it with like a cinematic ratio and all

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

most heart wrenching line from the finale

#my art#fanart#art#mcyt#evbo#tabi#pvp civ#this is pretty much like a screenshot redraw#envisioned it with like a cinematic ratio and all#evbo definitely being teary sayin all that#pvp civilization#pvp civilization fanart#finale#screenshot redraw#tavbo

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Best Live Action Short Film Nominees for the 92nd Academy Awards (2020, listed in order of appearance in the shorts package)

Since 2013 on this blog, I have been reviewing the Oscar-nominated short films for the respective Academy Awards ceremony. Normally, the Oscars are held on the last Sunday in February and we, the moviegoing public, are given more than a few weeks to seek out the nominated films. Not this year, as the ceremony was held at the earliest date ever (it reverts back to its usual starting date, the last Sunday in February, for the next two years starting in 2021).

There’s already been a winner in this category, but nevertheless here are the five nominated films for Best Live Action Short Film. Congratulations to Tunisia for two of the five entries, but all these shorts reflect the cinematic democracy that are the short film categories.

A Sister (2018, Belgium)

Also known by its original French title, Une soeur, A Sister is directed by Delphine Girard. It is the only piece among its fellow nominees that could be envisioned only as a short film. As such, its sixteen-minute runtime requires succinctness, the filmmaking as tightly wound as a clock. Late at night, a woman named Alie (Selma Alaoui) is sitting in the passenger seat asking the man (Guillaume Duhesme) for a cell phone so she can call her sister. We hear the first few seconds of this phone call. The screen cuts to black; next, we see a bustling room with numerous people gazing into computer screens, speaking to various people over headsets. We soon realize that Alie is dialing for an emergency call center. She is being kidnapped, and does not recognize the highway they are driving on. The operator (Veerle Baetens), confused by Alie’s coded language at first, eventually intuits what exactly is going on.

Alie and the operator exercise caution during these precarious minutes, as A Sister unravels in its teeth-grinding escalation of tension. Girard notes that the inspiration for A Sister came when she heard of a story of a young American woman calling 911, pretending that she was calling her sister – “it was the story of building a story of empathy and sorority that inspired [Girard].” Through meticulous research about protocols during emergency services calls that included interviews with said operators (who also made suggestions about draft screenplays), A Sister accomplishes a dramatic urgency that films with similar goals but last far longer never reach. The clever chronological edit in the film’s opening minutes contribute to that escalation; so too the decision to shoot from the backseat, obscuring Alie’s face to make the audience rely almost entirely on vocal delivery to understand her desperation and his paranoia (although the darkness of the surroundings can leave audiences confused in the opening minutes about who or what we are looking at). Not a second of A Sister is a wasted one.

My rating: 9/10

Brotherhood (2018, Tunisia/Canada/Qatar/Sweden)

Having made its rounds across the international film festival circuit, Meryam Joobeur’s Brotherhood is an international cross-stitch of a short film serving as an expression of Joobeur’s Tunisian roots. The film’s tragic outcome and dour tone throughout make is akin to Greek drama, where the ending feels predetermined and the characters – in what makes them essential – barely evolve. In a coastal, rural Tunisian town, a married couple and their two youngest sons make their living as sheep farmers. The landscape is rugged, their lives simple. One day, the eldest son – who has been missing for more than a year – returns home. With him is his teenage wife, wearing a full niqab, pregnant, and instantly attracting suspicion from the father. The eldest son and his wife met in Syria, where the former joined the so-called Islamic State (referred to by everyone else in the family by its acronym, Daesh – considered an insult to those affiliated with ISIS) out of desperation to flee his implicitly abusive father.

Brotherhood is indulgent in its languor, sometimes hanging onto certain shots well beyond necessary. Long cuts are welcome in cinema to allow the audience to meditate about what has just occurred; their emotional and philosophical implementation in Brotherhood is inconsistent. A constant use of close-ups and the film’s 4:3 screen aspect ratio reflect each parents’ stubbornness that their opinions about their situation is correct, that the eldest son’s belief that he is morally unblemished (he professes not to have killed, nor having been an accessory to killing another). The near-complete use of natural lighting - the overcast skies, the orange hues of older electric lights – lends the film authenticity. Joobeur, a Montreal-based filmmaker, has stated that she made Brotherhood to reclaim the humanity that the Muslim world has lost to the West since 9/11. From the red hair of the brothers, the ambiguity of the eldest son’s time in Syria, to the dramatic irony that closes the film, Brotherhood always challenges those views that Joobeur wishes to reclaim.

My rating: 7.5/10

The Neighbors’ Window (2019)

Marshall Curry is principally a documentary feature producer (2005′s Street Fight, 2017′s A Night in the Garden). The Neighbors’ Window, which he directed, is only his third narrative short film and, unfortunately, the final product is indicative of that – he has directed a handful of documentary features and shorts, but the techniques and lessons learned there are not always congruent to narrative short films. Here, mother Alli (Maria Dizzia) and father Jacob (Greg Keller) are New Yorkers with young children (early grade school and preschool age) who have settled into what they both feel has become a monotonous lifestyle. One evening, they see through their apartment window that, across the street, a younger couple have just taken up residence. Without pulling down any blinds and in their erotic euphoria, the younger couple start unpackaging (and this has nothing to do with moving boxes). Like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window (1954) but without the murder, Jacob and especially Alli will occasionally peer into their new neighbors’ apartment to voyeuristically observe.

The Neighbors’ Window has little to say beyond its assertion the grass is always greener on the other side – it pains me to have written such a cliché. Other than basic editing, this is a film devoid of any aesthetic experimentation or narrative interest. The film’s plot twist, inspired by a true story heard on the podcast Love + Radio, is not strengthened by the lackluster acting. The supposed emotional catharsis that should emerge in the film’s final moments is simplistic – redeemed neither by said acting or the film’s questionable screenplay. It is, at worst, tasteless. The premise of The Neighbors’ Window is indeed worthy of cinematic treatment – perhaps even as a feature – but Curry is not up to the task.

My rating: 6/10

Saria (2019)

It is a fine line between politically-tinged narrative/documentary filmmaking and agitprop. Bryan Buckley’s Saria, a dramatization of the events that led to the deaths of 41 girls between fourteen and seventeen years old in a 2017 Guatemala orphanage fire, almost becomes exactly that. Saria (Estefanía Tellez) and her elder sister Ximena (Gabriela Ramírez) are orphans at the La Asunción Safe Home. It is a safe home only in name, as Saria, Ximena, and the many other girls housed in the orphanage are victims of staff abuse or human trafficking. Saria and Ximena dream of a life far from the girls’ dormitory at the orphanage, and there have been mumblings about a joint plan between the boys and girls at the orphanage to cause a diversion in order to begin an escape, en masse, on foot, to the United States. Given that Saria is based on a tragedy, there is only one resolution possible.

However, despite being confined to that horrific ending, the film endows its two central characters with distinct personalities and aspiration to the extent that it can. In its twenty-two minutes, Saria not only depicts the squalor and prison-like conditions of the safe home, but the desperate humanity of its subjects – as if taking a page from Italian neorealism, this film has orphaned children playing orphaned children, but the direction and writing behind their performances can be frustrating. Saria is somewhat hampered by its editing, as the emotional impact of the escape scene to the film’s final minutes feel rushed. The film’s pre-closing credits reveal – that Saria is indeed based on actual events and no one has ever been held accountable for the deaths of the forty-one girls – is harmed because of the film’s prosaic editing.

My rating: 8/10

Nefta Football Club (2018, Tunisia/France/Algeria)

On its face, Yves Piat’s Nefta Football Club – another transnational production set in Tunisia – has all the hallmarks of a film that spirals into a disastrous conclusion. Yet what instead transpires is a witty comedy that mostly adopts the point of view of its two child protagonists. Near the Tunisian-Algerian border, Mohamed (Eltayef Dhaoui) and Abdallah (Mohamed Ali Ayari) are soccer-obsessed brothers bickering over who is the best player in the world: Lionel Messi or Riyad Mahrez (personally, I have never heard Mahrez in that conversation, but noting that he is Algerian and almost certainly the greatest Middle Eastern or North African player in history, this sounds like a realistic conversation). While heading home, the boys encounter a donkey wearing headphones and carrying bags of white powder. They take the “laundry detergent” home for their mother, with the intention to sell the rest to their neighbors. Somewhere in the desert, two men are waiting for their delivery donkey to arrive.

Don’t worry, those two men will never have a clue whatever became of their delivery. Piat came up with the idea for Nefta Football Club while recalling childhood memories of him and his friend sneaking out of their house at night, finding white powders that they believed to be illicit materials, and dumping all of this into a body of water. Nefta Football Club showcases a loving, hilarious relationship between elder and younger brother, as well as the perspective divides of the eldest brother’s teenage calculation and the younger brother’s innocence. Their life station is never fully explored, nor is it ignored by Piat. Piat’s screenplay – based on believable misunderstandings that are based on the characters’ personalities – is well-executed, as evidenced by its fantastic final punchline.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb ratings. Half-points are always rounded down.

From previous years: 85th Academy Awards (2013), 87th (2015), 88th (2016), 89th (2017), 90th (2018), and 91st (2019).

#A Sister#Brotherhood#The Neighbors' Window#Saria#Nefta Football Club#Delphine Girard#Meryam Joobeur#Marshall Curry#Bryan Buckley#Yves Piat#92nd Academy Awards#Oscars#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SEVENTEEN’s Happy Ending:

DIRECTING OUR DAYDREAMS [choreography]

Summary: The choreography in this song shows how we play out our fantasies in our minds, inventing the happy endings we don’t always seek out in real life.

A/N: My first real attempt at analyzing and explaining choreography -- so naturally it’s for Seventeen!

For lack of a better word (and lack of knowledge on dance), I’ve used the term “centre” to refer to whoever is currently singing/rapping in the song even if they are technically off-centre choreography-wise.

With the announcement of the tracklist of Seventeen’s 3rd full length album, An Ode, I found myself revisiting the Japanese version of Happy Ending from earlier this year. Here, I found an interesting pattern running through the choreography that adds to the message of the song and makes the ending... less than happy.

In this song the lyrics talk about the members imagining themselves as the main character in their own movie where they get their happy ending with their love interest. The lyrics make many references to movies, describing scenes like the fights they’ll win and the slow-motion moment they’ll have when seeing their love for the first time. In the video we get complementary shots that show our men in the hero’s role of classic movie genres -- with boxing rings, fast cars, and special forces scenarios all playing out in a very cinematic, wide-angle aspect ratio.

However, the lyrics and video also make a point of zooming out and placing us behind the scenes of these movies. For example, in the lyrics we get references to the end credits, as well as Wonwoo calling out the commands of the director (stand by, one two, and Action). Similarly, in the music video we see various members outside the idealized scenes -- Joshua as an author, Mingyu inspecting film, S.Coups in a sound booth with a car scene happening behind him, as well as many other shots of the members surrounded by A/V equipment.

Additionally, across many of the scenes we see digital effects added on top as if we’re watching someone editing the video in real time. All of these elements converge in the chaotic groups scenes that show all the movies coming together, with digital overlays, and lighting equipment in plain view. By doing this, Happy Ending draws our attention to the fact that these ideal endings are being crafted instead of coming true naturally.

On top of this, driving home the sense of fantasy and feelings of fabrication, many of the movie-like scenes either take place inside a warehouse -- looking very much like a set -- or in a dream-like abyss, where nothing exists beyond the victory moment.

The lyrics and music video create a cohesive vision of the daydreams we orchestrate in our minds and identify with on screen. Something that isn’t so easy to see in the music video is how the choreography for this song plays into the theme of directing our own fantasies.

Seventeen is well known for the performance component of their music. For many (myself included), it’s hard to find another K-pop group that holds a candle to the dancing that this group does on stage. Along with incredible physical skill, Seventeen has also shown great thoughtfulness in their choreography and how it can connect with the lyrical content of their music. A clear example of this is the Korean sign language that has been woven into the choreography for their song, Thanks.

In the case of Happy Ending there are the obvious references to the lyrical content, like The8 turning the pages in a book to the get to the ending, Mingyu and Seungkwan following the scrolling credits with their fingers, and Wonwoo making the gesture of a movie slate closing when calling out Action. But Seventeen has also thrown in a more subtle sense of story-telling that runs throughout.

Commonly in stage performances that involve vocals, whoever it is that is singing is usually centred on the stage, doing actions slightly differently from those around them, and often dancing a little less intensely. All of these things serve to draw attention to whomever is meant to be highlighted, while also making singing easier for that particular member. We certainly get that singling-out in this choreography as well, but Seventeen has managed to incorporate another element into the way that they use their centred member.

Sprinkled throughout the choreography we get moments where whoever is singing is also directing the members who are dancing around them. This is done in a few different ways in this song. Sometimes, like in the beginning of each pre-chorus, we see our centre perform a movement alone before being matched by everyone else

Other times we have the centre directing the movements of others like a conductor -- using hand and body gestures to draw the other members into the right patterns.

All over this choreography we have whoever is singing being somehow separated from the others and leading the motions as the rest of the group mirrors or follows them. In general, this technique isn’t especially uncommon in choreography. It serves to both highlight the singer, and add a bit of dynamism to how a group of dancers relates to each other. However, I rarely encounter it being used so many times in a single dance, and given the themes of the song, it seems much more likely that it is being used a tool to communicate the song’s message. By including this element running through the choreography, Seventeen is using their numbers to show how we play out our fantasies in our minds. It’s as if the person centering is the dreamer and the other members are acting out the story that brings them to their happy ending.

We can see this very literally in the way that the members backing Wonwoo begin to dance with fervor only after he calls Action.

With this theme in mind it’s fitting that it’s the person who is singing that gets this role of power. By being the one singing, they are the one responsible for telling the story and describing the fantasy they wish would play out. They are effectively narrating their daydream, which then comes to life through the other dancers. As the reins get handed off to the next vocalist or rapper, the one who is telling the story of the song switches over as well, and so our narrator changes identities.

Happy Ending makes it’s focus (in the lyrics, music video, and choreography) the way in which we fantasize about who we could be and what we could have if we were the ones calling the shots. The members of the group then embody this dream of making your own world through the way they have a single member directing the choreography. On top of that, many of the movements included in the choreography are quite powerful, playing into the fantasy of being a hero, and very energetic, reflecting their inevitable triumph.

With a title like Happy Ending and so much talk about being the hero and saving the day, it would make sense to expect some grand and glorious finale to this song...

And yet, this choreography ends on a note that may feel a touch out of place. Despite the upbeat music and the victory dance (the dabs) that we keep getting attached to the chorus’ happy ending / happy ending, the final moment of the song is somewhat reserved and brings the emotional tone of everything down. As the song comes to a close, Jeonghan charges to the front of the stage and the other members file in behind him, obscuring themselves from view. Finally, Jeonghan dips his head, breaking eye contact with the camera, and the music fades.

Though this feels very different from the rest of the song and choreography, this almost sad moment fits in very cleanly with the idea of him being our (current) daydreamer. This final moment feels like the return to reality. The music ends, bringing the daydream to a close, and our centre is reduced to just himself without his fantasies. To illustrate this, the choreography has the other members, who played the characters in his dream, disappear behind him, leaving us with an almost empty stage and a lonely individual. Along with this return to reality we also see a change in posture that has our strong hero fading into a mere man.

Throughout this song, the choreography places an emphasis on the behind the scenes aspect of the lyrics. We get references to books and movies that go hand in hand with the visuals chosen for the music video. We also get a repeated pattern of someone orchestrating their daydream through the control of the other members’ movements in the choreography. Despite the song and choreography maintaining a lively energy, and despite the final line of the song being, happy ending, ultimately Seventeen has chosen to end their performance with the return to reality. This final moment feels like a reminder that no matter how vivid the movie you’ve played out in your mind is, the happy ending you’ve envisioned doesn’t hold much weight if you don’t make it real.

thanks for reading!

MUSINGS MASTERLIST

#my.musings#seventeen#svt#happy ending#an ode#choreography#musings#kpop essays#explained#analysis#not.bts#this is one of the shortest essays i've writing on this site i think#well done me! they were getting out hand there for a while haha#my.svt

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music for Introverts: An Interview with Shuze Ren

Whenever the Composer and Sound Designer Shuze Ren sees an artwork—moving image, photo or painting—he immediately envisions its soundtrack. It makes sense, as Ren is a film composer who has scored films that have premiered everywhere from Telluride to the Clermont Ferrand Film Festival, and his projects have been featured in Variety.

Ren, who has lived in Japan, New York, China and Switzerland, studied film scoring at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, followed by graduate film studies at Columbia University. He was also invited to the 2018 Globes de Cristal, the French equivalent to the Golden Globes, for his outstanding work in cinema. A powerhouse with equal understanding for image and sound, Ren equally brings moods and landscapes to the cinematic language, which alters the rhythms of film and is a master at creating cinematic illusions. With influences that range from Johnny Greenwood to John Cage, Brian Eno, Bach in Tarkvosky and Zbignew Preisner, his trademark sound—for films and in music—is a kind of aural richness, rich with synth tones.

In his own words, Ren says: “I think what I lean towards is an aural richness, created by something for example, of falling water with a nostalgic synth tone, or a muted piano against the sound of thick whispering dialogue against the creek of footsteps on an old wooden floor. A combination of things that creates an image despite the medium being cinema. Think synesthesia.”

As Ren gears up for the release of his debut album coming out next year on the Maia record label, and is working on the score for a film directed by Swedish-Costa Rican director Nathalie Alvarez Mesen, he took some time to chat about nostalgic piano sonatas and Squarepusher, as well as composing beyond Hollywood.

Where does the real magic happen when scoring for films?

Shuze Ren: I score films rather untraditionally, I’ve been trained to do it the classic Hollywood thematic way. But for me what feels most natural is to get into the mood of the music that needs to be written. This is something that comes naturally, but the hard part is focusing or fine-tuning the appropriate resonance of emotion needed, once this happens. The real magic I suppose comes, as my compass/center has been realigned to the scene and I essentially select what’s needed whilst I play until the feeling releases, bit similar to finding something that is cathartic to the feeling. I’m not sure sometimes if I’m merely just someone who is sensitive to sounds and music that recognizes what’s needed like a stylist. Except I’m both playing and selecting at the same time.

What is your typical instrument of choice to begin with for scoring?

A synthesizer of some sort, a prophet 08 is good to create digital warmth for a diegetic score of an ‘indie mannered film,’ whilst a prophet 06 is ideal for a non-diegetic score for what I do. I use a synthesizer as a test to see what’s needed, I often tell people I work with, that I have a feeling that the model of a camera dictates the music more than you think or would like to think, and that the instrument is often acting as a color variant to the image. Sometimes I use digital signal processing of diegetic sounds to test this as well, when no keyboard is available.

How do you know what music fits for certain scenes?

Watching a lot of films, from all different genres etc. (4000 films is a good mark) and realizing that some great films have music that unintentionally distort the narrative or vice versa for better and for worse but most importantly knowing why. Having music in your ears at all times during your daily routines and different environments helps you create a gauge of how the same music works differently under different soundscapes and visual stimuli, a soft nostalgic piano piece can

be beautiful with the sound of autumn leaves whistling against the wind but at the same time feel piercingly provocative with the sound of rain and traffic.

How do you approach composition and orchestration?

I am a huge fan of Joni Mitchell, the singer songwriter. She’s also a painter. I approach orchestration as sound, like a paint palette each stroke adds something to the painting. They weave in and out, they clash, they resolve. I suppose you have to an understanding of theory to not think about the technicalities. But Instead of doing this with an orchestra, I create texture with the layering of sounds, effectively by obeying the principles of orchestration but towards all sounds and qualities of the instruments and not just in tonal notes. Another reason why doing post-production audio work as well as music can coincide together to create something unique to the medium of motion pictures.

While most people might not realize, sound is as equally as important as visuals in film and TV. Why is scoring so overlooked?

I read an old school audio book in the Cinémathèque Française, it was written: “You do not go to the cinema to listen to music.” I think this is true for me, as I think the epicenter is in Cinematic language and is what is the most magnetic. For me in the most beautiful instances, film music leaves you a vivid painting of a scene that makes you linger between dream and memory. As what you saw on the screen is what you picture, but the music paints the tone on top of it so well that it fits like a vivid painting that you can’t stop looking at after.

What is your approach to naturally and seamlessly connect audio with film?

Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa said: “For a scene to work with music and visuals, the scene must be shot in a way that depletes 50% of the visuals so that 50% of the music can fit.” Too pretty of a visual with music, and vice versa, will cause imbalance. Knowing this helps tremendously. However, there is a way where this ratio can be changed by incorporating carefully-selected sounds to the tonality, instrumentation, and sonics of the music. This in my opinion is what creates mood and complex emotions, an illusion. Just like in LOST IN TRANSLATION, actress Scarlett Johansson stares outside the hotel window in silence, as the music of Squarepusher comes in, this scene creates a feeling of longing. If the scene had sounds of the streets outside the hotel, or of the cleaning maid outside vacuuming, with the same music, this would create a feeling of sadness or passing, of some sorts; two very different adjectives in the cinematic world.

What is the focus of your forthcoming album coming out 2018/19?

My focus on my album will be to see how far this translation of senses from visual to sound and music will go. Some friends have been taking me to gallery’s/exhibitions of photographers and painters, and often when I see an artwork, I hear the music that could fit with it instantly. The focus of my album will be to try and translate accurately what I want to say musically so a specific color is perceived with the music, giving people a clear visual to the different moods/ vivid images I have felt in the recent years. Like the pianist and the book reader in a room. It will be music for introverts.

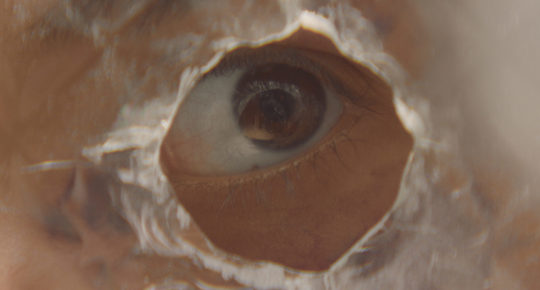

Image stills from “Shelter” by Natalie Alvarez (Gothenburg Film Festival 2018), Tear Of The Peony by Yuxi Li (Telluride Film Festival 2016), “Kiko” by Jamil Munoz, “Deux Assiettes Pour Trois” by Noe Dosen (Clermont Ferrand Film Festival 2017) and “Tail End Of The Year” by Chieh Yang (Taipei Film

Festival 2018).

Interview by Nadja Sayej.

0 notes