#emilio.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@mortemoppetere from here

[pm] Don't thank me. [del: Please.] I should have gotten there sooner. I'm sorry.

[pm] What? You didn't know. It's okay. You came. No apology

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

@mortemoppetere replied to your post “Whose the worst person in town?”:

Funny. Forgot to say yourself.

The question wasn't 'who is the best person in town' though.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIMING: Recent, late march PARTIES: Emilio @mortemoppetere & Inge @nightmaretist LOCATION: Near/in a tree in Worm Row SUMMARY: Perro sniffs Inge and chases her into a tree. She's stuck there and so a conversation between Emilio and her follows. It soon spirals. CONTENT WARNINGS: Parental death, sibling death, child death (all mentions), physical torture (threats, mentions of past events), alcoholism (implied), animal abuse (implied vaguely)

Despite living in a much nicer neighborhood now, courtesy of Teddy, Emilio still tended to feel more comfortable in the seedier parts of town. He felt much more at home in Worm Row than he did in Teddy’s neighborhood, even now. He got less odd looks, less people who seemed intent on letting him know just how little he belonged. So, when walking Perro, he tended to gravitate back to Worm Row. He checked up on his apartment, made sure Jeff was alive, kept an eye out for any threats that might need taking care of. Perro seemed to enjoy it, at least; Emilio got the feeling that the dog felt more at home in Worm Row, too.

So it was a little bit of a surprise when the little bundle of fur puffed up as they walked down the street. Perro’s sudden defensiveness was accompanied by a familiar shiver down Emilio’s spine, and he grit his teeth. Something undead. Perro usually preferred nonhuman companions, so it probably wasn’t a vampire or a zombie. Could have been a nonsentient variety of undead, or…

The answer occurred to him about the same time he spotted it. The mare. The one from the factory, the one who’d known his mother, the one who’d tortured his brother for days, the one he was bound not to kill. Emilio grit his teeth, grip tightening on the leash. But Perro, for his part, wasn’t any more a fan of backing down than his owner was. He was scared; Emilio knew that. Mares had that effect on animals. And Perro didn’t cower when he was scared anymore.

With surprising strength, the terrier dragged his owner towards the mare, barking and snapping his teeth and doing all he could to look vicious instead of small.

—

She didn’t stretch her legs a whole lot these days. With the muscles the slayer had ruptured on the mend, most movements ached mercilessly, constantly reminding her of her failure, of those dark days in the factory. Inge despised it. She despised herself. She despised the hunters and Siobhan and felt herself grow rotted with hatred, embracing it with glowering eyes.

Today she was on the move. She’d driven up to the casino but was taking a walk from Dis’ underbelly domain towards one of the shadier pawn shops. She had some things to sell, an itch to buy something silly and obscure, an endless craving for a small materialistic win. But of course something as simple as that could not be done without a complication. Perhaps she should have waited until after sundown before braving the streets (ironic, as the darkness was so often considered dangerous in places like this), but alas. It was too late.

Her attention was pulled by the initial bark of a small dog. Not this, not again. Inge wondered what it was about her that made dogs in particular so angry at her existence — why couldn’t it be an animal with less sharp teeth and no instinct to kill? As her head whipped towards the sound and took in the depth of the situation an expression of anger and what she’d refuse to call fear washed over her. Cortez.

Of course that fucker had a stupid little dog.

Inge increased her pace, starting to run to the best of her ability as pain shot from her back and gut to her legs with every beat of her feet against the pavement. She wasn’t going to be able to outrun them. Not with her injuries. Not in general.

But the sky wasn’t dark yet though it was early in the evening, so there was nowhere to go. Inside a store? God knew that this Cortez might back her into a corner there. She did what she’d done before: she laid her eyes on a place the dog couldn’t reach and climbed. Lucky her, that she was somehow in one of the few streets in Worm Row that had a fucking tree. Letting out a groan of pain, she pulled herself onto a branch, watching as the dog continued to pull on his leash.

“Control your beast!”

—

Perro pulled against the leash in a way he usually didn’t, desperately barking and growling. Emilio wondered if the dog was reminded of the mare that had broken into his apartment months ago, the one he’d stuck a knife in and sent on his way. Was what the dog felt now similar to what Emilio had felt when being fed on by that mare, or the one before it? That icy fear, that stutter step of his desperate heartbeat? Or was it something closer to what the detective felt in that factory, with his brother’s blood coating the floor and a different kind of terror clawing at his throat?

Either way, Emilio couldn’t fault Perro for his reaction, couldn’t deny him the release of venting his frustrations through his tiny, vicious squeals. His leg ached as he picked up the pace to follow, to let Perro take chase, but the pain was worth it. Inge seemed uncomfortable, he thought; she was running, was moving as quickly as she could, and he liked that the same way he’d liked seeing her pinned to the wall with a sword in her gut. It didn’t undo anything that had been done, didn’t sew Rhett’s leg back to his body or stop the long-dead corpses from swimming into view in the corner of Emilio’s eye, but there was something satisfying about seeing one of the people responsible suffer, even if she wasn’t suffering much.

He watched her retreat, wondering absently where she’d go. Would she run into a store, breathlessly accepting the humiliation of being chased by a dog that didn’t even come up to her knees? Would she climb a fence in an alley, knowing that Emilio likely wouldn’t be able to follow? He noted the hunched way she ran, thought with some quiet vindication that she must still be feeling the effects of that blade he’d put through her gut. He wished he’d put it through her throat instead, but if he’d done that, he might not have gotten Rhett out of that factory at all.

(Would it have mattered much? Emilio and his brother would likely both be dead at the hand of the banshee’s scream if he’d killed the mare then, but what would it matter?)

The mare scrambled up a tree, and Emilio let out a sharp laugh. Like an animal, he thought absently. He thought it felt right, then thought he should feel bad for thinking that. The guilt might come later, when he thought of Ariadne and Wynne and how they loved her, but it was absent now. Instead, there was only a dull satisfaction as the mare pulled herself onto a branch in a way that sounded painful.

Emilio eyed her for a moment, leaning down without breaking eye contact. He put a hand on Perro’s head, scratched him behind the ear even as he continued to bark and growl and place his lone front paw against the base of the trunk. “Good dog,” he said slowly, deliberately. Reaching into his pocket, he retrieved a treat and dropped it into Perro’s mouth. “Bueno.”

—

She’d been staying inside during the daytime hours ever since the factory. Inge wasn’t the reclusive type — she preferred to take the world by storm. Whenever she was alone, she tended to work on her art or broaden her mind, but those activities had felt short for her as her body proved still as frail as that of a mortal. She’d become something restless, something too paranoid and in too much pain to go out as often as she had before. During the night, she ventured out, as during the night she was free. Then, she could access the astral where her body wasn’t this corporeal, weak thing. Then, she could be whatever she wished to be in another person’s dreams.

She should have stayed inside today too, that much was clear. This was a small town. This was bound to happen, them meeting again. She’d hoped it would be somewhere at night or somewhere more public – a grocery store, in line with their products of the evening or, perhaps more in line with their past meetings, in a bar.

Inge pulled her legs up, her features strained with pain as her body folded up on the branch. She wasn’t sure what it was, this effect she seemed to have on dogs in particular, but she was very much over it. Especially if those dogs had owners with personal vendettas against her. The stupid thing had put his paw against the tree, was still barking and growling despite the praise it received. She wanted to kick it, but knew better than to get down.

“Vete a la mierda,” she cursed, “Y tu perro.” The dog’s stupid ears pricked up at those words, as if it was used to expletives. Inge clutched the trees trunk, considered climbing up higher. If she had a heart that worked, it would be beating faster with adrenaline (not fear) now. She pushed herself a little higher, reaching up. It didn’t seem like the hunter had an axe with him, but she doubted he was unarmed. Her back hurt, her gut hurt — but she was damned if her body became marred once more by a Cortez’s blade.

—

He had a knife in his pocket. Actually, that wasn’t quite true. He had several knives in his pocket, bumping and clanging up against one another in a way that was comforting to him and unnoticeable to anyone else. He could reach for one now, could toss it at her in that tree. He knew how to spin the blade just right so that it would sink into her skin when it got to her, knew how to make sure it hurt. He could put one in the joint of her shoulder. It’d probably knock her down from the tree, send her sprawling onto the ground.

But then what? If he knocked her out of that tree and Perro went in for a bite, odds were she’d lash out. Kick him, hit him, throw him away from her. He was a small dog; it wouldn’t take much to hurt him. And if she did, Emilio knew what his instinct would be. He couldn’t kill the mare without breaking the promise, and he couldn’t break the promise without killing himself. And while he might not particularly want to live, he didn’t want to die like that, either. He didn’t want to give the mare or the banshee the goddamn satisfaction.

So, he settled for watching. Perro barked and growled and pretended to be a bigger thing than he was, and Emilio crossed his arms over his chest and tilted his chin up and did the same. Neither one of them could present a real threat here. Neither one of them could do shit for the respective pounding in their chests. But there was some comfort in baring your teeth, even when they’d never find anyone’s throat.

“Your pronunciación is bad,” he said flatly. “I thought you spent time in Mexico. Isn’t that where you met my mother?” He pretended the word didn’t burn on his tongue. Her Spanish was fine, really; better than most people who didn’t speak it as their first language, even if it wasn’t quite perfect. But Emilio needed something to say, and insulting her was the only route that made him feel decent, the only thing that kept his mind from dragging him back to that factory with the stench of blood clinging to his nostrils. “How’s the tree? Maybe you can try jumping over to the next one. Get yourself home like una ardilla. Maybe you won’t fall on your ass.”

—

She would like to think she had cornered the market in making people afraid. It was something she had made into an art, something she’d honed her skills in over the past years. She was the monster under the bed, the scary clown at the circus, the birds that pecked out eyes, the water in which loved ones drowned — she didn’t get scared. But Inge was, at the end of the day, nothing but a survivor. A raging thing, refusing to give into the notion that perhaps she should be dead.

And Emilio Cortez – just as his mother and all those like him – put that in danger. Even if his dog was small. Even if he’d had the opportunity to kill her thrice now and hadn’t. Even if he was bound to Siobhan to never kill her. Still, she felt unsure of her unlife when across from him and though she refused to call it fear, it came close to it. Like a nasty cousin. Discomfort, anxiety, a thread of unease with what the slayer represented and what, in turn, she was made to be.

Ingeborg could not do anything from where she was in the tree. She could not reach into the astral and to get down was to be in an even less comfortable position than she was in now. The dog might bite and then there’d be glittery blood and people flocking to them and seeing something they shouldn’t. There was the hunter with God knew what weapons. She felt herself simmer with rage and that other feeling too, that unease. She’d felt it in that factory too — the lack of control, of things being turned against her. She no longer in control, the way she was in dreams.

“Yeah,” Inge said, remembering what Mona had said, “That’s where I fucked your mother.” It was said with conviction, lies were an easy enough comfort and she needed something to wield. She dug her fingers into the branch holding her up, nails pressing into the bark. “Nah, I’m going to stay right here, it’s right comfortable. What are you gonna do, just stare? Kind of perverse, you know, to just be staring at women stuck in unfortunate positions.” She readjusted, grimaced. “Your dog is horrid.”

—

Did this make him feel better? Genuinely, he wasn’t sure. It had been a long time since he’d felt the way he had in that factory, where she’d tortured the only family he had left for days on end and thought herself righteous for doing so. The desperation that had clawed at his chest then had been the sort he hadn’t felt in a long time, had taken him back years and miles until he was right back in that living room with the blood on the floor. Wasn’t that what it came back to every goddamn time? Emilio would never leave that fucking room. His corpse was still rotting on those floorboards with his daughter’s. He could pretend he was somewhere else for a while, could haunt Teddy’s house or Xó’s apartment, but people like Ingeborg would send him back to that room time and time again with little more than a word or a look or a leg on the concrete floor.

So what was the point of this, then? Trapping her in a tree for however long it took for the sun to sink low enough in the sky to allow her to access the astral and scamper away wouldn’t put his soul to rest. Her taunts didn’t serve as an exorcism that might free his restless spirit from that living room floor, and the barking dog wasn’t a priest who might speak the last rites over his cooling corpse. A ghost was still a ghost, even when it fought back. Even when its heart still beat.

He didn’t feel much more alive standing at the base of this tree than he had in that factory, where he’d begged to die for his brother’s sins. He didn’t feel in control here, didn’t feel powerful. He hadn’t felt powerful in a long time, since the day the world ended two years prior with a too-small corpse on a bloody floor. Was this what it meant to rage against the dying of the light, then? It was so much quieter than he thought it would be.

“You must have been very bad in bed,” he said dryly, “if she wanted to cut your head off after. Not sure I’d brag about this.” The idea of his mother sleeping with anyone undead was somewhat laughable. Elena Cortez had always been strong in her convictions; that was why she’d felt killing her son was the best option available to her the moment he stepped out of line, after all. Emilio felt far more discomfort at that thought than he did at any of Inge’s taunting. “I could run to the general store across the street and pick up some salt, if you’re tired of me staring. Nice circle around the base of the tree. Since you’re so comfortable, I’m sure you wouldn’t mind staying the night there.” Did he mean it? He wasn’t entirely sure. It wasn’t as if he could do much against her. At best, he could serve as an irritation. But… Emilio was good at being irritating.

Glancing to Perro, he hummed fondly. “Es un buen perro,” he corrected. Perro looked back to him, tail wagging in spite of his fear at the mention of his name. Emilio offered him an encouraging nod in return, and the little dog went back to barking and growling at the base of the tree.

—

Was she becoming a sentimental woman now, who didn’t know what was good for her? She should have left this town behind that time Rhett had put her in the basement, should have given into the instincts that had done her good all her undead life so far. But in stead she had stayed, giving into the human urge to be around people that made her feel good. In stead she had attempted to exact revenge against that same very hunter and failed miserably. And after that too, she had stayed. She had stayed after what had happened with the ghost tours.

And now here she was, stuck in a tree, looking down at the offspring of a hunter whom she had run from. Had she been wiser, then? What was it that had muddled her mind that she was in a position like this? Inge did not think herself so weak, that she’d risk herself like this for others. For sentimentality, for affection.

She called it pride, then. Pride was what had kept her in town. A refusal to be run from a place she enjoyed living in. It was her right to be here. It was strong of her to remain, wasn’t it? Not weakness, but strength. Certainly, her affections for Dīs and others played a role in that refusal to leave, but it was a sign of character. That was how it was. (But how strong could that character be, if she ended up stuck in a tree? If she was glaring down at a dog that was barely as big as her torso, tense at the sight of a Cortez cornering her.)

She checked the time. Sundown couldn’t come fast enough, but it wasn’t there yet. Damned spring. If it was winter, it’d be dark already and there would be no problem. No inner turmoil, no unraveling, no need to keep listening to that grating voice and the even more grating barking.

“I was excellent. I’d tell you to ask her, but …” She lifted one hand, gesturing vaguely. “I guess she’s dead.” She hoped the words could be like a knife between the ribs, but she doubted it. Her lie was paper thin. She was cornered — and if Cortez was serious about what he’d said next, she might even become stuck. “And leave your dog with me? I doubt you’d be so stupid.” Inge had no intention to hurt the dog, but she didn’t mind making it seem like she was that brand of cruel. “You’ve seen my handiwork, haven’t you? How’s Rhett doing, anyway? Sleeping well?”

She was a fool, staying in the same town as the both of them. But perhaps so was Emilio, or at least, perhaps she could make it seem that way. “Es un perro muy apestoso.” She could barely smell the thing. “Igual que tú.”

—

Exhaustion clung to every inch of him, though not the kind that could be resolved with a nap or a cup of coffee. Sure, his body was tired — he couldn’t remember the last time he’d even attempted to sleep through the night — but that wasn’t what made his bones ache. There was a different kind of exhaustion, one far harder to combat, and it had been hanging over Emilio’s head like a cloud for years now. He tried to find ways to ease it. He killed people who were a part of the group that brought on that apocalypse in Mexico that only he had noticed, and he did it slowly. He made them hurt for hours or days and he pretended it could be compared to the way he’d been hurting for years now. And it used to come with a jolt of energy, like the kick of caffeine in the early mornings, but it was so muted now. Everything was.

He could make the mare miserable, if he tried. He could take a page out of Rhett’s book, could trap her someplace with bright lights and no access to food and see what happened. The thought of it made his stomach churn, made him think of Wynne’s face outside that van or the way Ariadne had been so sure that he was there to finish the damn job. Had Rhett felt good about it after, he wondered? Had he felt anything at all? Was it Emilio who was broken, Emilio who was wrong? His mother had thought so. Rhett had, too, sometimes. And maybe they were right, but they were no longer here to say it. Did that count for something?

“Yeah,” he replied to Inge’s statement, though he felt a sensation as if he was watching the conversation from the outside. His mother was dead. It ached the same way it always had, and he wondered if that was normal. Should he feel differently about her now? Should he grieve less with the knowledge that, had she survived, it would be Emilio rotting in the ground somewhere now? How did you mourn someone who you’d loved when they hadn’t loved you back? How did you wrap your head around a grief that was only ever going to be one-sided? “You’re dead, too,” he said flatly, because it was easier to antagonize than it was to unpack the questions that haunted him now. “So I guess you don’t get any bragging rights.”

She made a good point, though Emilio wouldn’t admit it. To walk to the store would mean either bringing Perro along and allowing the mare a chance to escape or to leave him alone with her, and neither option got him what he wanted. The very idea of leaving his dog with the woman who’d spent days torturing his brother, who had removed his leg from his body and found it a funny game to play, made his breath catch in his throat. She wouldn’t hesitate to hurt the dog, would she? She wouldn’t think anything of it at all. And Emilio couldn’t stand the thought of failing something else that relied on him, couldn’t live with it.

So he shrugged, shifting to sit down on the sidewalk with his bad leg stretched in front of him. “Guess we wait, then.” When the sun went down, she’d be gone. He couldn’t do much to stop that. But he could inconvenience her until then, could piss her off and ruin her day and pretend it made any kind of a difference.

The mention of Rhett brought the acidic taste of acid to his tongue, though he showed no external sign of this discomfort. He’d made sure Rhett was safe from her, had begged a promise out of Siobhan in a way that had made no difference in the end. Perhaps he should have found some way to include more in that, should have tested his luck to see if he could protect everyone he cared about from the pair of monsters with blades and nightmares to spare. If Inge wanted any sort of vengeance now, he hoped she’d just take it out on him. At least he’d earned it. “Maybe I’ll pick up where he left off before, hm? Bright lights, salt. How many swords do you think I could put through you before you passed out? Got plenty more of them. Could pin you to the wall like a poster again, see how long it takes for you to get free just so I can do it again.”

He couldn’t kill her. He had to remind himself of it, had to force himself to remember the promise he’d made. But Siobhan never said he couldn’t make her wish she was dead. That was enough to keep him going, at least.

She insulted the dog, insulted him, and Emilio huffed and rolled his eyes. Maybe if he were more present, he would have taken more offense to it all, but it felt like a scene from a movie. He was watching it happen from that living room floor he’d never get away from, seeing it all play out against the backdrop of a bloodstained wall. “Maybe you’re smelling yourself. You’re the rotting corpse here.”

—

For a moment she wondered, why the slayer wasn’t dead. The rumors had spread about the eradication of that clan of slayers (clan, because referring to them with vampiric terms was a mental powerplay) and yet here he stood. Alive and kicking, with an annoying dog and a reluctance to kill her that he’d had to pay for. Inge wondered how it could be, that he still lived, how his mother had died, how many people he’d lost. She felt no pity, just a numb kind of interest to press her thumb on the sore spot until it bruised even darker.

She hoped whoever killed his mother had made her suffer. Her fingers trailed over the jagged skin of her neck. Would she be proud of her son, for having marred her gut as he had? For having pinned her to a wall and leaving her there? Or would she just be disappointed that he hadn’t stuck the sword in her neck and cleaved until her head had rolled off and she’d become dust? It was an ugly train of thought, one that served to justify Inge and not do much else. To think of such things was to forget her own transgressions, to paint the others as villains and vindicate her. Not that she felt particularly victorious, up in this tree.

As Cortez pointed out that she was dead she let out a sound of frustration, though it could also be one of boredom. She didn’t think of herself as dead. If she was dead, her body wouldn’t hurt as it did. If she was dead, she would not be feeling that anxiety crawl through her body, wouldn’t have known euphoria and love and rage. She’d seen death, the permanent and definitive state of it. She was between. No, better: she was above. Above mortality, above finality. “That’s just your wrong opinion,” she quipped back, pressing a hand in her side. There was no blood underneath that skin, perhaps not even functioning organs — but she was here. She was vulnerable – and didn’t that in and of itself make her alive? “Did she suffer? Did they hack her head off? Stab her with a stake in the heart?”

She wouldn’t penetrate his nightmares, she wouldn’t meet him on the ground, but she’d do this. Turn words into daggers and hope some of them would land. If he’d trap her here, she’d make it a miserable time, that was what she vowed to herself as she watched him sit down.

But it seemed it was a two way street of miserability and as the slayer talked of ways to make her life worse Inge found her muscles growing tight with that thing she refused to call fear. Even now. She was lucky, wasn’t she? That he didn’t have the salt to trap her. That he didn’t have that van his brother had used to lock Ariadne away. That his dog was part of the equation, a weakness that she could hypothetically exploit. That he had no family to call to come assist him in trapping a mare and doing to her what had been done to his brother.

Even with all those things in her favor, she felt unsafe. The threat hung in the air, unanswered, and she had no reply for a moment. She remembered the bright lights, Rhett’s gruff voice, his hand in her neck as she was immobilized. She remembered Italy and starving. She remembered being stuck on the wall. She remembered Hendrik.

Perhaps that stirred her most, the way her mind went to her ex-husband. Not Sanne and her head chopped off, but that marital rage that had loomed over her days as a woman bound to the home. Inge stared darkly at the slayer, gritting her teeth. There was a quick remark hiding behind those, she knew it — something clever and unaffected, something that told Cortez she still had the upper hand, even if he held the proverbial knives. Literal too, probably. “Empty threats,” she said, “You could have killed me months ago. Look at you.” She felt her hand dig for her own switchblade. “Sitting there. Waiting me out. You pose no threat if all you do is speak.” Why did it sound like she was egging him on? She grit her teeth again, hating the words that came out. They hardly rationalized the situation.

She carved a star in the tree’s bark. She didn’t care about the insult, saw no use in attempting to dissuade the others opinion on undead. His mind had been made before he was born. She stared at her watch and wondered what time the sun would go down and if he’d stay where he was until it did. She still refused to call what she felt fear.

—

She let out a sound he couldn’t pinpoint, a noise he didn’t have the social aptitude to unpack. Had he hit a sore spot, reminding her of her own demise? The undead didn’t sleep, he knew that. But if they did, would she have been plagued with nightmares like the ones that had led to her death? Did she still think of it, the way she’d suffered and died? Victor had confided in him once that he felt pity for the things they killed. They were people once, weren’t they? He’d asked in a conspiratorial whisper, terrified by the prospect of being overheard. They were people, and they died. It’s not their fault they came back. It must be scary. I think we’re doing them a favor, Milio. I think that’s why we do it.

There were certainly other slayers who thought that way, though Emilio knew Elena would have disapproved. To their mother, the undead were little more than threats to be eradicated. Protection of humanity, she said, was the duty their name carried. They had no obligation towards the dead, no responsibility to free souls that were already lost.

(Emilio wondered, sometimes, if that was why his mother had been able to move on so easily from Victor’s demise. If they had no obligation towards the dead, was she freed of her motherly duties the moment Victor’s heart stopped? Why, then, did Emilio cling so tightly to his?)

Of course, any pity he might have felt towards the mare in the tree had died in that factory. She was a person once, but she wasn’t one now. And if he was being honest, it had little to do with her unbeating heart or the way she’d barely bled when he’d stuck a sword through her gut. He liked Metzli, thought of them as a person even when they struggled to apply the word to themself. He thought of Zane as a good man, even though he was a dead one. Ariadne loved Wynne the way only a person could.

No, if Inge had forfeited her humanity, it hadn’t happened with her death. It had happened, at least in Emilio’s mind, on that factory floor. It had happened with his brother, who had perhaps forfeited his own humanity with the locked door of a van, left in a heap with pieces removed. Wasn’t it a person’s actions, after all, that made them something else? A monster wasn’t a monster because it had sharp teeth. A monster was only a monster when it used them.

Inge was a cornered animal now, too far away to bite but not prevented from bearing those teeth in his direction. She asked about his mother, and Emilio remembered the brightness of her blood, how strange it had seemed. When he’d wandered the streets during that massacre, every color had been dulled except the red.

He didn’t answer the question, though he suspected Inge would have reveled in knowing the truth. Had she been there, would she have celebrated? Emilio thought of his mother’s corpse, the way it was in pieces by the time he found it, spread across the street like celebratory confetti. He thought of Rhett in that factory, his leg in one place and the rest of him somewhere else. Had he come in later, would he have found his brother in the same state he’d found his mother in in the midst of that massacre? Would the red have been just as bright, just as terrible?

“I don’t have to kill you,” he said, and he pretended that he couldn’t didn’t burn. Should he have killed her the first time he met her, in that bar? Should he have followed her out and sawed through the scar his mother left on her throat, finished the job Elena had started? If he had, would Rhett be whole now instead of broken? Or would that cycle of vengeance have found Emilio rather than his brother? He imagined a world where it was him on that factory floor, where pieces were removed from him one by one. Would anyone have come for him the way he’d come for Rhett? Who would have stood where he stood if he were in his brother’s place, who would have offered their life for his? No one who deserved such a fate the way he had, he knew. No one who should have.

Even so, he couldn’t help but think that that world might have been a better one. Given the choice, Emilio would always prefer to be the one in pain rather than the one left to stand by and watch. He’d have given his own leg to sew Rhett’s back onto his body, would have given his life to get his brother from that factory with his heart still beating. But things like that weren’t options awarded to him. Emilio had never been able to save anyone he loved. All he could ever do was avenge them after he failed.

And what an empty vengeance it was, standing at the foot of this tree. How meaningless it felt. “I’d rather do to you what you did to him,” he said darkly. “Cut you apart piece by piece. Legs, arms, ears. Maybe I carve into your chest, see what state your heart is in. I don’t think you use it much, anyway. Shouldn’t matter if I take it out. You curious what it looks like? If it started rotting when you died?”

It was probably an empty threat. He could hardly pretend he was able to climb the tree and grab her, after all, not when his leg ached just sitting here. He could try to knock her down, but not without risking Perro getting caught in the crossfire. He could track her down later, find out where she lived and turn her living room into a nightmare the same way his had been in Mexico, make it so she never left her bloodstained carpet even when she was a whole damn country away from it. But he was so fucking tired. Just talking to her made him feel heavy, made his stomach churn. If he tortured her until she begged him to stop, would it make him feel better? Would anything?

So maybe the threat was empty, but so was he. That was just the way things went.

—

What she had one to Rhett – or had attempted to do – she had never done before. It wasn’t like Inge didn’t bite back, it was just that she didn’t tend to do it after the fact. Not like this, not under the guise of revenge. There had been a hunter she’d killed once with the bang of a gun and a body dropping to the floor, but that been in a moment of self-defense, in the heat of the moment.

To track down a man, to take him down and then bring him someplace else to elongate his suffering before snuffing out the life within — that had been new. But there was plenty else that was new, wasn’t there? There was this cursed town that had dug its claws into her, keeping her from turning around and running. There was something within her that cared about a young, naive mare, a part in her that had been filled with a rage at the notion that she should have to leave once more because of one warden. There was Dis.

There had been Siobhan, willing to help a hand because of her sadistic nature (one she never should have trusted, that much was clear now) and there was that rare touch or bravery. There was not much left of it now.

And maybe it had been a little too late. She had never struck back at any of the people who had slighted her before, had she? Not in a way like this, not this violently and bloody and coldly. Sure, she had left Hendrik and disappeared on him, but never had she hurt him the way he’d hurt her. Never had she been brave enough to do such a thing. And then there was Sanne, who had given her so much – this new life, these powers, this endless source of creativity – but who had taken so much at the same time. What had Inge done, besides watch as she was murdered? Was that the retribution she had claimed for herself? Watching the woman who had killed her die at the hands of others? She had thought about it, at times. She had thought of ways to scare a woman who fed off fear and had not succeeded, had never let herself get her pay back until that day. Sanne had screamed for her and she’d abandoned her maker so she could live.

There were things stolen from hunters, messes created in their houses or other significant places. Little jabs or payback for her having to run. But there had never been something like this. She had placed herself above proper revenge, valuing her own life more than exchanging eyes for eyes and she had thought herself wise. She had wanted to kill Rhett. She had thought herself more entitled than hunters did when it came to killing her kin. She had thought it just. Her time. She had thought it would have felt good.

And she still thought now that it would have felt good if she had succeeded. If all that carnage had ended with a dead body and a chapter closed. But in stead everything had gone to shit. In stead Elena Cortez’ son had come in and had done something, somehow to convince the banshee to take the hunter with him.

So the point — it was lost on her. Even if now she still imagined slamming a knife in Rhett’s throat. Even now, she thought of that factory with its stained floor and thought of an alternate reality where Siobhan had undone both the men’s lives in one fell swoop, as she was certain the other was capable of. But these would remain fantasies, as her thoughts of revenge had often done.

In Emilio Cortez’ head, there were also fantasies. He spoke of them now, weaving an image of a long process of pain, searching how far he damage her body without killing her. Inge was all tight muscles in the tree, staring down at him and wondering when he’d get up, when he’d blind her with some kind of light or pin her to the wood she was clinging to. When he’d start. If he ever would, or if he would just let the threat exist between them, like the promise he’d made Siobhan. I may not be able to kill you but I can make you wish I could.

Fine, she admitted it to herself. She was afraid. She had been afraid in the factory. She had been stirred by the sight of the blood and the toes and the leg. She had looked at herself in the mirror in the days after, wondering what kind of woman she even was any more. Someone who created horrors in dreams but winced when presented with them in front of her? She turned her fear into art, paintings of red and gore that jumped off the canvas. She was afraid now, like she had been afraid in the bunker, like she had been afraid sleeping as a human.

She climbed a branch higher, her face scrunched up with pain. She stared at him and knew that one day, a scene like this would plague one of her sleepers. But that was to be then, and this was now.

“I didn’t do it,” she bit. “I gave him dreams. If you want to return the favor of that stolen limb, you’ll have to find the fae who bound you. She took him, nail by nail, toe by toe, then the foot and then the leg. She.” Inge knew there was no use in it. She’d watched. She’d taken away Rhett’s ability to flee into slumber, turning all the furniture in his already rattled brain upside down, endlessly taking and given the way someone once had with her. “You could never recreate the things I made him dream, though I suppose I could give you a taste. Your mother wasn’t immune to my touch, so I reckon you won’t be either. Do you dream, Cortez? Do you want to see my dreams?”

The goading was pointless, as it all was. Rhett was still not dead and it was not yet time to beg, to make the fear wash over her face and make it apparent. The slayer remained on the ground, after all, even if his threats now sat in the tree with her.

—

When he thought of Rhett in that factory in the days before Emilio arrived too late to save most of him, he’d never spent much time wondering who had done what. He’d never bothered trying to imagine whether the blade fit better in Siobhan’s hand or in Inge’s, never stopped to think about who’d tied him up or who’d gripped his hair or who’d sawed away at the bones in his leg. What did it matter, in the end? What difference did it make? His brother had started one way and ended another, and two people had forced him on the journey that made it so. Did Inge think herself blameless for not dirtying her hands with the blade? Did she think there was no blood staining her fingers because of it?

He thought of Lucio, on the day of the massacre. He thought of the apology in his eyes, the way he’d choked on it as it rose from his throat. It wasn’t his uncle’s teeth that tore through Juliana’s throat. It wasn’t Lucio’s hands that snapped Flora’s neck. It wasn’t Lucio who left those corpses to rot in the floor of a house where they should have been safe. It wasn’t even Lucio who’d killed Elena, though her death had been the goal that started the whole ordeal. But when he’d apologized, when he’d pleaded with Emilio to forgive him, what had it mattered where his hands had been? His daughter’s blood was on Lucio’s hands just as much as it was on the vampire’s who’d killed her. Rhett’s blood was on Inge’s hands just as much as it was on Siobhan’s.

And both, he thought, stained his own hands, too. Rhett’s blood was still caked beneath his fingernails, Flora’s was still seeping into his skin. Juliana, Rosa, Edgar, his mother, even Victor… Emilio carried at least some responsibility for what had happened to all of them. He loved the people he loved, and every last one of them bled for it. He could point a finger at Inge and it was deserved, but there was always a second pointing inwards as well. Siobhan held the knife, but Inge was still to blame. And so was Emilio. So, always, was Emilio.

“You think this means anything to me?” It was the same thing he’d said to his uncle once, when Lucio’s apologies formed a noose meant to strangle them both. This quiet street in Maine, lined with shops and trees, flickered into that chaotic scene in Mexico now, with bodies on the concrete and blood in the air. Emilio’s nostrils flared and he swore he could smell it, swore he was choking on it. Inge was Lucio was Emilio was everyone who’d ever sported the blood of someone he loved on their hands like a pair of bright red gloves that went up to the elbow. “You think it matters? You were there. You made it happen. I’ll do what I like to you, to her. I’ll make sure you feel it.”

He wished it were truer than it was. He wished there was some way to take this feeling in his gut and remove it, to pluck it from its home within his ribcage and shove it down her throat instead. If she felt what he felt, if she knew a fraction of it, would it change the look on her face? Would it change anything at all?

He let out a sour laugh at her threat. Did she think nightmares scared him now, when he’d walked in on a waking one in that factory? Did she think there was anything she could show him while he slept that would ever compare to a factory floor coated with his brother’s blood, to a living room slaughterhouse where his daughter’s corpse had already begun to stiffen? What could she show him in his dreams that was worse than what reality had given him? She’d made a mistake, he thought, in that factory. She’d played her cards too early. She should have known better.

“Do it, then,” he goaded, calling her on the bluff. “Come into my bedroom, climb inside my head. Try to make yourself into something worth being afraid of. I sleep with a knife under my pillow. All you’ll be doing is saving me the trouble of tracking you down later, making it easier for me to do to you what was done to him. You watched, didn’t you? You sat there, you enjoyed the show. You can do the same this time, too. I’ll set up mirrors so you can watch me cut into you, yeah? Let you see while I pull your guts out. One at a time, I think. Lungs, liver, kidneys. You think they grow back? Probably not, huh?”

Despite the content of the threats, his voice remained flat. He got no joy out of it, no reprieve. Would following through make any difference? He thought of all the vampires he’d killed, the ones he’d tracked all the way from Mexico. He’d done it slow, more often than not. He’d killed them in pieces, done far worse than what Inge had watched Siobhan do to his brother. Had any of it ever filled that bottomless chasm in the pit of his stomach? Had any of it ever made him feel like a person again? Had any of it served to peel him off the living room floor, to wash the blood from his hands? He doubted taking Inge apart piece by piece would make him feel any different than he felt now. Saying it certainly had little effect, but what more was there for him? What else did he have? This was all he was now. This was all he’d ever be. He knew that.

The sun was sinking now, and he knew it was a matter of time before it was low enough for her to hop away into the astral where he couldn’t follow. He couldn’t tell if the thought was a disappointment or a relief. He wanted this to be over, but he didn’t know how he wanted it to end. At the foot of the tree, Perro barked and growled. Emilio watched him, wondered if the display made him feel any better or if he, too, was just putting on a show.

—

She had known guilt before. When she was younger and she was human or when she’d been newly transformed. She’d be bogged down by shame and remorse about things, because that was how she was taught. On Sundays the pastor would go on and on about the inherent sin of all the people in his congregation. Shame and guilt were taught and Inge had been an excellent student. Hendrik, of course, had always known how to make these feelings grow tenfold. And then she had died and come back as a creature of consumption. If humans were born in sin, then mares were most certainly sinful creatures in nature — and with every meal she’d take, she’d feel her guilt grow.

But four decades had passed since then. She had divorced the man who’d humiliated and shamed her. She had grown distant from the church, even if she had not severed herself. She had learned to enjoy feeding, to find a purpose and a passion in it. She had lost Sanne. She had lost Vera.

She understood that guilt was a wasted emotion, like a bitter aftertaste. It was best not felt but when it was, let it be for the situations that actually demanded it. Like those losses — the gruesome axe to Sanne’s neck and the slow death of her daughter. Those were situations where guilt was warranted and perhaps served some kind of cruel purpose. Those were situations where she couldn’t not feel the guilt, even if she could try to suppress it or maneuvre around it.

When it came to Rhett and that factory? The only regret she had was that she hadn’t slit his throat sooner. She didn’t feel any guilt for the severed leg, even if she had been put off by it initially. She didn’t feel any guilt for the repeated nightmares, the constant intrusion and mental anguish she’d delivered so effortlessly. She didn’t feel any guilt towards Emilio, who had found his brother chopped up and disoriented. She didn’t feel any guilt for the vitriol spilling from her lips.

And maybe there was a part of her that struggled with what Siobhan had done. How she hadn’t discussed it, this mutilation, how Inge had come back to the earthly plane and had seen blood gushing. How strange it was to see such suffering in reality, rather than in her handcrafted nightmares. She grappled with it, sure. She had been afraid of the sight, shocked and disturbed in a way she wasn’t often — but she didn’t feel guilty. It would be a wasted emotion, especially on a man still alive.

A man who’d intended to slowly starve one of her ilk, who would have kept her in that bunker until she’d started convulsing or something of the sort. Guilt was wasted on people like. And Emilio, who went into detail of how he’d dissect her? He didn’t deserve her guilt either. Her guilt wouldn’t undo what had been done, would not make the slayer below her forgive her and would only serve to make her feel worse.

Inge stared down at him. He was right. It didn’t matter, what she had or hadn’t done, “I watched. I let it happen. And whenever he reached unconsciousness I made sure he would have no peace, either. I watched him as he watched me, as he watched all the others he must have harmed and killed in his lifetime.” She clung to one of the branches. “You’re not doing anything now, Cortez, besides saying a whole lot of nothing.” As was she. But she was only a predator when the sun was down.

She didn’t doubt it, though, the reality that one day Emilio Cortez would come for her and make her suffer like Rhett had. An endless tango of vengeance, suffering for suffering, eyes for eyes and legs for legs. There was another regret she had, actually: she regretted having debased herself to a creature of revenge. For having squandered her position in this town with nothing to actually show for it but a bad taste in her mouth.

She should have just brought down the knife in Rhett’s chest the first night she met him, that time she’d fed on him in his van. She should have put him to sleep and murdered him before she could even know more intimately what things he was capable of. She should have vanished and left no trace. What eye was Emilio going to take then? Would he know to hunt and threaten her, if she’d been more subtle and more decisive, if she had just delivered a defensive but fatal blow and had disappeared?

Perhaps. If she felt guilt, she felt it for herself.

“You assume I’d be so foolish to give you the luxury of waking up aware enough to come for me,” she bit back in return, “I do appreciate the inspiration you’re giving me. Maybe I’ll have you dream of that factory and have you watch as Siobhan and I continue our work on your brother. I can immobilize you in your sleep, you know? Make you more powerless than you are now. Make you a spectator.” Inge spoke and spoke, clinging to her bravado as if it was the one thing keeping her upright. She shivered at the thought of his threats — knew that whatever damage he’d do would be more permanent than her nightmares. “I’d make you hold the bone saw. Make you lick the blood of your fingers. How about that?”

—

There had been a period once, when he was young and stupid and so much softer than he should have been, where Emilio was uncertain about the things his mother expected of him. Killing spawn and wights wa sa simple thing, a thing that made sense; they were monsters who looked like monsters, and there was a mindlessness to the way they attacked that was undeniable. But the first time he’d seen a higher vampire, he’d hesitated. It hadn’t looked like a monster, hadn’t looked scary. It looked like his mother, like his uncle, like his siblings and his cousins. It looked like someone instead of something, and it threw him off.

It had been a moment of doubt that he was ashamed of later, and it hadn’t gone unnoticed. Not by his mother, and not by the vampire, either. It was one she’d captured for training purposes, locked in the shed to show him, and it had begged. It had called him mijo, had pleaded for its life, and Emilio’s hand shook in a way it never had before. Nothing he was expected to kill had ever spoken to him before that moment.

His mother had been unable to let it slide, of course. Killing spawn and wights and mindless things was a part of a slayer’s job, but it wasn’t all of it. You had to kill the others, too. The ones that talked, spinning lies to better catch their prey off guard. The ones that would drain someone dry and go home to sleep in a soft bed after, the ones who were dangerous in ways that had nothing to do with their fangs or dietary habits. Emilio needed to learn that lesson, and his mother had been more than willing to teach it to him. Monsters didn’t always look like monsters; it was a hard thing for little boys to understand.

So, she’d taught him. She’d locked him in that shed with that vampire, still chained. And it had begged for the first day and pleaded for the second but on the third, when it was starving, it had snapped like a wild dog. It had thrashed against the chains, it had strained against them in hopes of reaching his neck. By the time those chains snapped, by the time the weight landed on his chest and the teeth found the arm he’d thrown up to protect his throat, he understood what his mother wanted him to learn. The stake went in, and the hand holding it didn’t tremble. A day later, when the bleeding stopped and the door opened, she held her hands behind her back and looked down at him with an unreadable expression on her face. Things like this can pretend to feel, she’d told him, but they can’t really experience it. They’re good liars. You need to remember that.

He wasn’t sure how right she’d been. It seemed blasphemous to say, but Emilio had seen more evidence of the undead feeling than his mother had ever meant for him to. He’d seen it in Metzli, in Zane, in Ariadne. He saw their grief, their guilt, their love.

He saw nothing of it in Inge.

When his mother spoke of monsters, he thought, this was what she had been referring to. This thing that would lock his brother in a factory, would torture him in his own mind while her companion tortured him in the physical realm. There was something particularly sinister about that, about taking away even the limited escape that existed in the unconscious mind. Siobhan was a monster, but Inge was one, too. Worse still, she was a monster like the one in that shed; the kind that pretended to be something else at first.

Was she proud of it? Did she tell the story with a smile, brag about the damage she’d done? Even in hunters, Emilio often found such behavior distasteful. It was why he didn’t spend much time at the hunter bars, why he preferred drinking among humans. He didn’t care for war stories. His nostrils flared as she recounted hers, shameless in the way she spoke of what she’d done. “If you weren’t a coward in a tree, I’d show you what I can do.” But she didn’t care to be called a coward; he knew that. It didn’t bother her the way it would have bothered others. Monsters didn’t mind being insulted; they cared about what they could sink their teeth into when the talking was finished.

Was he worried, then, that she would sink her teeth into him? That she’d make good on her threats and find him in his dreams, make him relive that day in the factory from a different position? He felt a little sick at the thought, though he was careful not to let it show on his face. He’d had nightmares before, without help. He’d continue having them just the same, whether she invaded his sleep or not. “What would you do, then?” He sneered, baring his teeth like an animal. “Keep me asleep and in dreams until my body gives out? Not unless you want me to wake up like you. No hiding in the astral then.” The thought made his stomach churn, but he knew enough to know that Inge would hate it more. “You’d have to let me wake up sooner or later. And when I did, then what? I’m very good at finding people. I found you in that factory. I’d find you again. You can be in control while I sleep, when it doesn’t matter. But here, I think I have you beat.”

It was a bluff, though it was a good one. Any loss of control made Emilio feel a little too much like that kid in that shed, with a locked door sitting between himself and the night sky and so little room to move. But he was good at hiding his anxiety, good at swallowing it. It was one of the first lessons that shed had taught him.

The sun sank lower, and it was almost a relief, though he never would have admitted it aloud. He wanted this to be over, one way or another; if Inge departed, he could tell himself he’d won, could pretend he’d come out on top. He could go home and drink until he couldn’t see straight, could put a salt circle around the couch he planned to pass out on, could subject himself to nightmares that were his and his alone. And it wouldn’t be good, but it would be better than this. Anything had to be, didn’t it?

—

It was not hard to imagine the kind of dreams she could make Emilio Cortez dream. Inge’s imagination was a dark and endless well, inspiration gathered from the nightmares she’d endured decades ago and all the horrors that had followed since. She was an artist and fear was her dearest muse and there was so much of it in these corners, in these conversations.

There was her own fear for what Cortez might do to her, should he actually get his hands on her. How long her suffering at his hands would stretch out before she’d either get away or die. There was fear for even the stupid little dog, though that was instinct and less rational than her fear of the slayer. She could imagine making art based off his threats, a sculpture of organs picked apart and served, of mirrors showing distorted reflections of a mutilated self.

She had made dreams based off the way his mother had chased her, that feeling of imminent death nipping at your heels. An axe head slamming against your windpipe and neck, slowly attempting to undo your head from your shoulders. Coming down and down again and never severing it fully, always coming back to crush those tendons again. Blood gushing but life continuing, the glint of the silver in the air before it reaches down and then, perhaps, getting away and being chased again.

She made dreams of angry husbands and hospital rooms, of mental institutions that had once been and would hopefully never be. She could make Emilio Cortez dream horrible things. She could make him saw through the bone of his brother and have that stupid dog of his devour the flesh, have him coat himself in the blood of his kin. She could prod and poke in his subconscious, try and figure out a way to exploit the massacre that had undone his family and twist that into the dreams. She could make him get chased how she was chased by his mother, stick him to a wall, put him in a van, tie him to a chair, starve him and make him fall endlessly as around him horrors unfolded.

She could, but she wouldn’t. Inge didn’t give people nightmares to exact revenge. She didn’t pick her sleepers for reasons like that. She picked them at random, she picked them because she liked their bedrooms or how they slept, because she had encountered them once in public. She broadened their minds, stretching them by making them fear something that was only and purely in their head — the way her mind had been stretched ones. She inspired. She fed. She didn’t do it out of maliciousness.

Her talents would be wasted on this slayer.

“Would you? If you really wanted to, you’d come up here,” she retorted. They were at an impasse. Neither of them was going to close the distance between them, neither of them was going to bring out a knife or a drowsy touch tonight. Maybe later, he’d find her. Maybe then, he’d pin her down again and do what he had been threatening her with. But tonight it seemed neither was making the first move and in stead their weapons were carefully crafted words, shaped like daggers made of threats. And they burrowed, didn’t they? At least, Emilio’s words were nagging her, itching under her skin, making her grow tense and afraid in that stupid tree.

“I’d have you wake but be gone whenever you were truly awake,” she said, “As I always do.” Save for that one time with Rhett. And time time a slayer had been in the room with her as she disconnected from her sleeper. And… there was probably another time. Inge narrowed her eyes at him, which were growing more red as the sun grew closer to being gone. “Would you? Find me again? Your mother never did. You forget how easily I can move. I could be in Mexico like that. In Canada in the same time. You could track me down, but could you keep up? No.”

That was, if she left town. If she put miles and miles between herself and Cortez, but also between herself and all the things she’d grown to love and care for in this town. Inge hoped, selfishly and cowardly, that they could remain at this impasse, though she felt it was wishful thinking.

At least there was something she’d been hoping for that she could count on. The sundown. It always grew dark and it was a comfort whenever it did, especially these days. There was no doubt about what she would do once it was dark. Sure, she could hop into the astral and appear in front of Emilio, put him to sleep and drag him into some kind of horror show — but that wasn’t her intent and most likely never would be.

No, Inge wanted to leave. To go home and sit with herself and the conversation. With what had happened at the factory, what had happened with Elena, with the healing wound in her stomach. She wanted a bottle of wine and perhaps even a second and to then float around her astral until the sun rose.

And so when the sun was fully gone, so was she, not wasting a moment before leaving the earthly plane where she was a humanoid creature that could be picked apart, verbally and hypothetically physically. She left, gone from the yapping dog and the angry slayer, the threats of mutual destruction that might never come to be. But it would be in the uncertainty of what if that she’d have to sit with — not just for the night, but perhaps for all of Emilio Cortez’ hopefully short rest of his life.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[pm] I'm done arguing about this.

I am not paying for your shitty advice.

Nope, somehow they're even more annoying than you are. Kind finds kind.

[pm] I didn't get you the first singing toothbrush. You're really stuck on this. Kind of embarrassing for you.

I don't think asking someone to pay for your help is the same as extorting.

My partner is amazing. And funnier than you. And not annoying. [user frequently calls his partner annoying to his face, but is the only one allowed to think this.]

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obsessed with stories that preface their own tragedies. They stare you dead in the eye and tell you it will end badly. You watch the characters hurdle towards their doom, unable to do anything but watch. They'll give you hope that this time everyone will make it out, that just this once everything will be okay, only to snatch it away at the last moment. and when you're left grieving the end, you have no one to blame but yourself because they *told* you this was going to happen. there was no other way this could have ended

#gnawing on this#this is about uhhhh#moby dick#don't laugh.#but also#hadestown#the sparrow#do you know how hard it is to get obsessed with a random sci fi book from the 90's#who am i going to talk to it about.#emilio is rapidly approaching blorbo territory but that's for another post#gweh

824 notes

·

View notes

Text

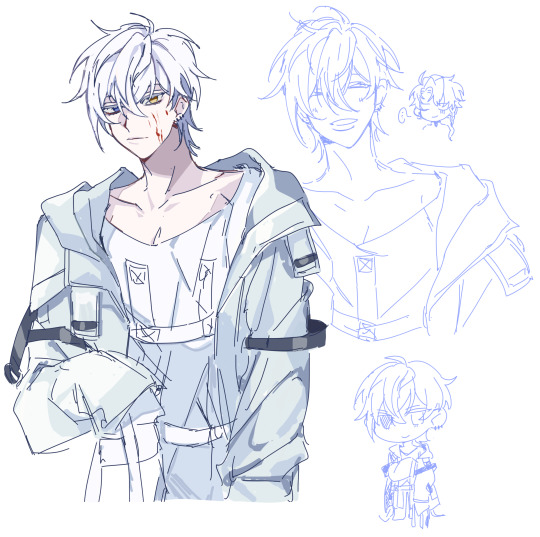

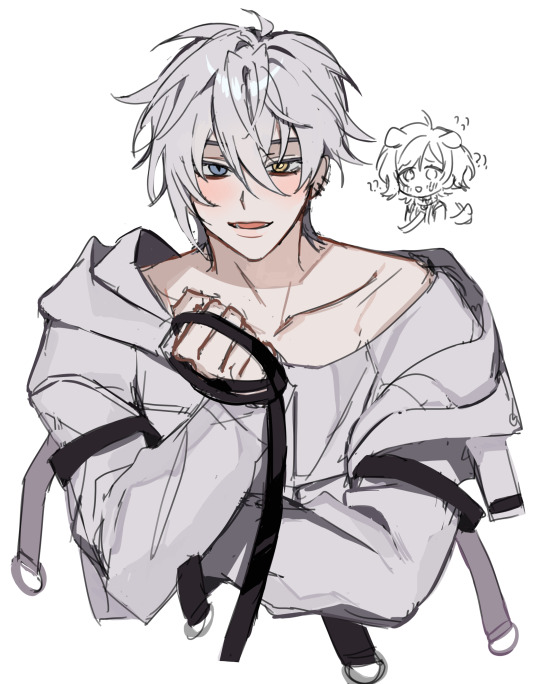

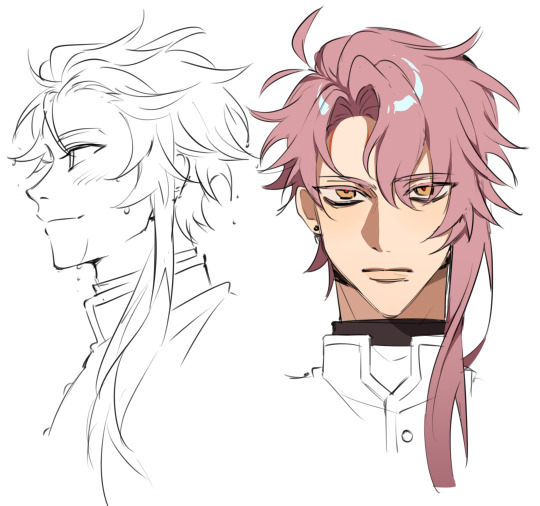

misc ymkr doodles frm 2023/4

#yumekuro#my art#realised i neva posted all of these here oopzzzzz#i hate this game so much <- was destroyed in february w the triple emilio cuit nanashi banners#im joking. this is literally the only game i gaf ab

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

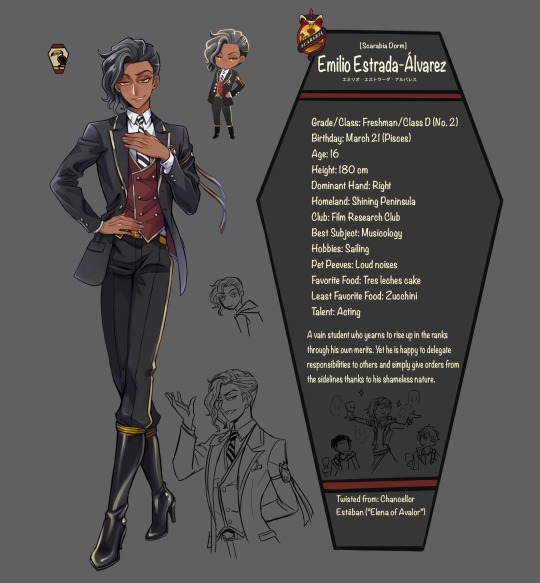

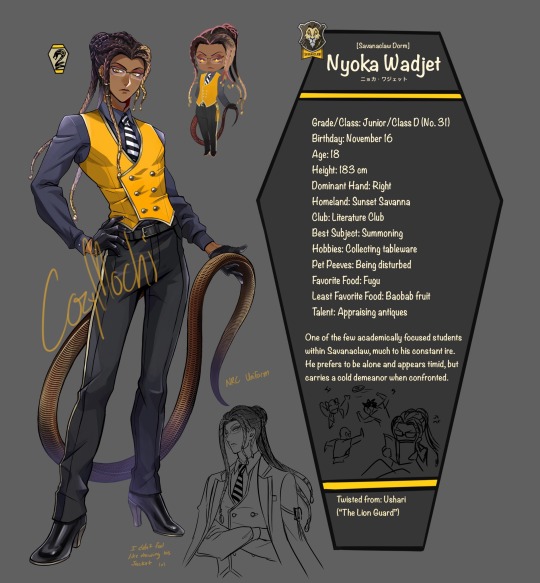

I had a bad day, so I compiled the few NRC boys I have. Also corrections were made on all three both visually (because I made too many errors before that I missed🤦) and info wise because I made minor changes (so if there’s contradictions, that’s why.) I should have updated Emilio’s render altogether because it’s pretty old compared to the latter two, but I don’t feel like it.

But, I’ll link Emilio, Cecil, and Nyoka’s original posts anyway, since they include a bunch of expressions I still like and convey the vibes™️ better. That, and for my own self-reference. Okay, I will no longer spam or clog up the dash with these things. Also credit to @oddberryshortcake cuz the boys are also semi collaborative 🤭 uhh, that’s it.

Ko-fi

#my art#twst oc#emilio estrada alvarez#cecil mugwort#nyoka wadjet#twstposting#emi’s homeland is still made up as no twst rep for an LatAm equivalent exists. …Yet.#When that happens it’ll probably not change his homeland but it will be within that area.#AS FOR EVERYONE it’s hard to explain how much dumb lore they have beyond those two sentences.#They got families and statuses and signature unique spell magics — all kinds of nonsense#twisted wonderland

788 notes

·

View notes

Text

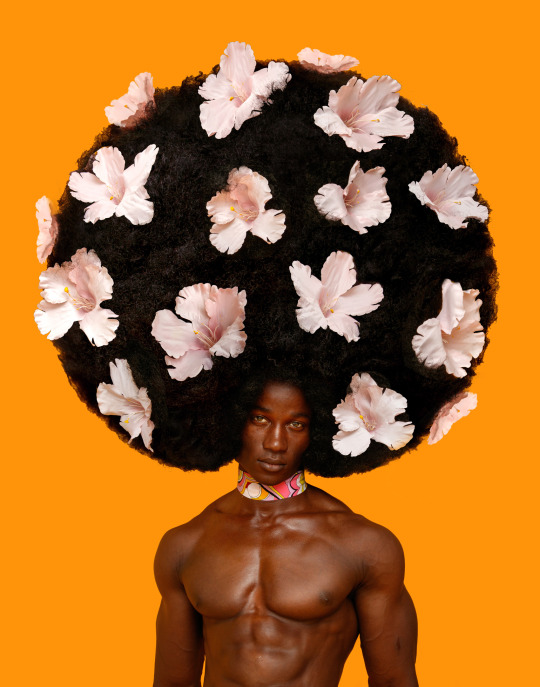

the higher the hair, the closer to God - Hamidou Banor by Baldovino Barani x FACTORY Fanzine

#flowers#diana ross#pucci#emilio pucci#baldovino barani#hamidiu banor#hamidou banor#factory fanzine#hair#muscle#big hair#beauty#pam grier#vintage

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS TOOK FOREVERRRRR 😫

but anyway my twst ocs :3

#my ocs#twst#twisted wonderland#ocs names from left to right —>#emilio cruz#sinn saelee#amphai saelee#toma kaimana#coquin#LITERALLY STARTED THIS IN THE BEGINNING OF SEPTEMBER#twst oc

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

EMILIO SAKRAYA

via Instagram Stories (12/26/2024)

344 notes

·

View notes

Text

@mortemoppetere replied to your post “[pm] Hey, kid. Are you okay? [....] Ariadne told...”:

[pm] It never really does, I think. [...] You need to look after you, too, Wynne.

[pm] I don't feel it yet. I'm seeing a lot of people crying but it's hard. You know? Also, she was Ariadne's best friend. So it is harder for her. And I don't mind looking after her in stead.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIMING: Current LOCATION: Outside the Keep PARTIES: Emilio @mortemoppetere and Daiyu @bountyhaunter SUMMARY: Emilio bumps into Daiyu while investigating. CONTENT WARNINGS: Abuse (hunter), sibling death (past), lots of talk about inhumane imprisonment

If he was going to break into a facility full of supernatural prisoners and stage a prison break, he was going to make sure he didn’t get anyone who didn’t deserve to bleed out killed in the process. That was a fairly important aspect to this whole ordeal, the kind of thing that Emilio wanted to be sure of. He’d fucked up with this kind of thing before, had freed Joy’s supernatural captives without thinking, and it hadn’t ended particularly well for anyone involved. So… he was going to do it right this time. He was going to… research, or whatever. He was, at the very least, going to plan his way in before actually doing the breaking and entering part.

The blueprints the necromancer had given him were a good start, but Emilio knew he needed to see the place in person. He needed to observe the shift changes, needed to determine when the best time to stage a break-in might be. He was quiet as he strolled the perimeter, forcing himself to take strides that were uncomfortable with his bad leg but quieter than dragging it behind him the way he normally did. Four steps this way. Guard at the door, but he’s on his phone. Looks like he’s got a radio — need to take him down before he can use it. Nonlethal — he might not know what he’s doing.

It was a quiet narration, an echo in his mind. He was into it, but not so much that he lost sight of the area around him. If anything, he was hyperaware of his surroundings when he was like this. Aware enough, it turned out, to recognize the strides of the person moving towards the building from just outside the shadow where he was standing.

He hesitated a moment. If he’d seen her a while ago, when all they did was bicker online without any real understanding, he would have just let her go in unbothered. But now, after their last interaction… He snaked out a hand to stop her. “Daiyu,” he whispered, trying to catch her attention without catching anyone else’s. “Hey.”

—

It had been a fair while since she’d moved up in the Good Neighbors and was now part of Winnifred’s inner circle. Daiyu did not try to think too much about what it meant, what it made of her. When she did think of it, she thought of it in terms of how those around – and still away – from her would think of it. Her father would think Winnifred a foolish woman with a heart that bled in a way he could exploit, and so would her sister. They’d think keeping the creatures alive just to lock them away a waste — would suggest further action. Experimentation. Selling parts. Selling whole things. Pitting them against each other.

They’d call her a bleeding heart, too. A stupid little girl, for falling in with something like the Good Neighbors. Enticed by that notion, by the idea of goodness. Hunters were born to protect, but the Volkovs knew better than that. You didn’t get rich through protection. And though Daiyu was making a buck off her work, it was nowhere near what she could be earning.

But she kept at it. There was always conflict to find in anything she did, so this was no different. She went out into town and the forest and took out the creatures, shifters and monsters that plagued the town. She tried to remember she was savings lives. Only taking out those that should be. That had earned it. She collected her money and didn’t worry about rent any more. She slept in a soft bed with a new duvet. She was fine.

Sometimes, when she went to the Keep to do a shift there, she brought along a bit of brain or blood she’d gotten off a kill she’d done for another bounty. She slipped the gore to angry vampires or zombies and did not think about the implications.

She was scheduled again today. Scheduled, as if she had a fucking job. And in a way, that was what it was, wasn’t it? Some people worked for mega corporations. She worked for Winnifred, who made really good hot chocolate and who was doing something good. Daiyu moved to the Keep with a backpack slung over one shoulder, her car abandoned a few miles back in the name of security. She was unsuspecting and not thinking about the implications of the ziplock bag with an aufhocker brain and so when someone’s hand appeared from a dark corner.

Daiyu responded as she was trained to, smacking the hand aside with a flat palm and getting ready to pounce. But it was just a whisper, and a familiar face. Emilio Cortez. A liar, a slayer, a dog owner, a saver of her life, but only on a technicality. “What. The. Fuck.” She pushed him back into the shadow. “What are you doing here?”

—

She slapped his hand aside, and he’d been expecting that. He pulled back before she could slap anything else, before she could do any kind of damage. He studied her carefully, tried to work out why she was here. At first, he thought she might have the same goal he did, but it was a notion he quickly pushed aside. Since his tenure in Wicked’s Rest, since his softening, he’d met only a handful of other hunters who thought the way he thought. Kaden, whose philosophy seemed close to Emilio’s even if they still disagreed on parts of it. Andy, who gave up hunting altogether and didn’t seem to regret it in the slightest. But other than that? Jade still thought of the undead in much the same way Emilio had prior to the massacre and his uncle’s hand in it, even if she was more open to supernatural creatures with beating hearts. Rhett probably would have ended up killing him if Ophelia hadn’t come along and shifted things just enough for him to make an exception for Emilio’s failures. Parker, Owen… every other hunter in this town seemed to be, at least on some level, what a hunter ought to be.

He didn’t know Daiyu well enough to think she was much different. He’d met her twice now, in two different scenarios, and he trusted her only a hair more than he might a complete stranger. But he knew she didn’t hunt indiscriminately. He knew she took bounties, and didn’t have much interest in things outside of them. He knew he’d never seen her hunting a sentient beast, never heard her talk about them in a way that sent up red flags. He knew that he didn’t have a lot of allies here, and that the information the necromancer gave him was good but not enough. He knew that Daiyu was walking towards the Keep with a purpose, and not being stealthy enough for that purpose to feasibly be the same as his. He knew that Daiyu could be swayed, too. She was stubborn — maybe even as stubborn as he was — but not immovable. If money was what she was after, Emilio could get that. He still had a fairly sizable chunk of the cash Levi had given him stuffed into his mattress, and it wasn’t like he was using it. He could buy Daiyu out, if it came down to it.

So… either he’d gain an ally here, or he’d get himself killed. It was a coin toss. But Emilio had never minded gambling so long as his own life was the thing on the table.

“Thought I’d go for a walk,” he replied dryly. “See the town, visit the prison for supernaturals. Real tourist destination, you know. On all the maps.” He kept his voice low and quiet, careful not to attract any attention from anyone else. Meeting her eye, he grimaced slightly. Heads or tails. Fifty fifty. Here we go. “Caught a case. Client has a friend who got grabbed outside her apartment. Tracked her here.” He nodded towards the building. “I looked into it. I didn’t like what I found.” He paused, tapping his finger against his knee. “I’m breaking it open. And I could use some help.”

—

The Good Neighbors practiced in the shadows. This was a no-brainer that even Daiyu could get behind. It was how hunters operated too, after all. Flaunt your position as a human who chased and killed creatures with supernatural powers and you might as well paint a target on your back. (She was not very good at not doing this — though she understood the need for secrecy she was a very bad practitioner of it, in part because she was a horrible liar and in another part because she had little impulse control.)

It was troubling that Emilio was here. That he was lurking in a shadow around the Keep when he was decidedly not involved with the organization it housed. She’d know if he was, right? Someone would have told her. Right? It wouldn’t be unprecedented that she was left in the dark about something, but in this case she would have been told, if another hunter had been added to the team. Yes. Certainly. Winnifred would have informed her of it. So then why was Emilio here, if he wasn’t part of the team? Her face was filled with suspicion that only got affirmed when the slayer spoke.

Daiyu wanted to knee him in the groin for a short moment and run away. It would be a good temporary solution to this problem he was throwing her way — the knowledge that he was planning on causing trouble for the Keep and the organization that kept it filled. The judgment he passed against the place he called a prison. It was the latter she grappled with most, the moral conundrum that Emilio was offering her by pointing out the flaws of the place. He was going to make her think about the implications with words like these and Daiyu didn’t want to.

“Your client’s friend probably grabbed or bit or ate a few people herself,” she said coolly. Or at least, she tried to sound cool. Like she wasn’t going to have a long think about whatever was about to transpire. Like she never ever lost sleep over kills or kidnappings. “What, you don’t like dangerous supernatural individuals being separated from the people in our town so they can’t eat, drain or bite ‘em? Weird. I think I remember you killing a vampire not too long ago.” She moved her weight from one leg to the other. “Breaking … it … open … yes, sure, explain to me why that’s a good idea, wiseass.”

—

Emilio wasn’t much of a planner. For most of his life, he’d let other people do that. His mother called the shots when she was alive, pointing him in whatever direction she believed he needed to go. As they got older, Rosa did much of the same, primed to take over as head of the family when it was her turn. (It would never be her turn now.) The only planning Emilio had ever really attempted was his desperate hope to get Flora away from a life he didn’t want for her, and how had that ended? His only real attempt at a plan had ended with everyone he’d ever loved dead. Didn’t that say all that needed saying about his skills there?

But… He wanted to be better. He wanted to plan something that worked, wanted to help people instead of hurting them. He didn’t always have to be a blade, did he? He could be something else, something better. For Nora, who needed that now more than ever. For Wynne, who’d always been given so much less than what they deserved. For Teddy, who was never as happy as they pretended to be. They all wanted him to be better for himself, and he knew that. But if he couldn’t manage it, if he still couldn’t quite see himself as a person instead of a thing, wasn’t it all right if he tried to be better for them instead? Wasn’t being better the thing that mattered more?

This could be a step, he thought. A step towards something that was more than a weapon, even if it was still something less than a man. He could help people here. He thought of Zane, who’d really only needed a steadying hand. He thought of Metzli, who’d been good the moment they had the choice to do so. Some of these people might belong here, but from what he could tell, Raisa’s friend didn’t. That had to mean there were others who didn’t, too.

“Come on, Daiyu,” he said lowly. “Even if she did, is this the way to deal with it? If someone’s a problem, you take them out. I support that. I do that. But sticking them in a cage…” The thought made his throat go dry, made his mind go back to that goddamn shed, made his palms sweat. “It’s fucked up. What’s the endgame here?” Human prisons were fucked enough, but at least they maintained the illusion of attempting to reintegrate prisoners into society, even if that wasn’t the reality. Emilio had a feeling this particular prison didn’t share the same views. Letting someone rot in a cage for the rest of their days was so much worse than just killing them. “Explain to me why it’s a good idea to keep them locked up. You really believe it’s right?” He paused for a moment, eyes darting to her duffel. “What’s in there?” There was no reason for her to bring a lot of supplies here. Emilio had a feeling whatever she had was for something she thought was important inside. He was going out on a limb here, but he hoped it’d pay off.

—

When she’d been ten, her father had taken her down the back of the estate, where spare and broken down cars were stored and there was a place like the Keep. Not as big, not as well-hidden (and yet just as protected), but made with a similar purpose. A holding place. Never for long, but it was the same. Barred rooms, locks that clicked and humanoid creatures that looked enraged, desperate, exhausted or all three at once. Daiyu did not remember a lot of her youth, but she remembered that day. His hand on her shoulder, almost paternal, and then in her neck as her eyes trailed away. Fingers digging in the soft skin behind her ears, palm pressing against the vertebrae in her neck. He’d reminded her: they are not human. He barely had to say it for her to remember that lesson. He’d filled her hands with buckets, had made her carry them down to the wild wolves. They had been heavy, but she’d been training for years by then. She managed. She placed the buckets down. Water. Raw meat. They are not human.

They called themselves hunters, her family, but they were more like poachers or smugglers at times. Cutting deals with researchers and magic users that lift on the fray of morality, selling them parts of if not full shifter corpses. There were the fights, the vicious displays of beast on beast violence. Not as organized as the fighting ring she’d visited – or so she guessed, at least – but similar. Similar enough to turn a profit.