#eirik cod

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A little bit about me:

✭ I'm Maxine or Jason, whatever you want to call me, both are valid.

✭ He, She and They

───────────────────≫•◦ ❈ ◦.

Catalog of my comics

.◦ ❈ ◦•≪ ──────────────────

─LOVE BLOSSOMED IN THE LIGHT OF OUR SINCERITY

❝Same tastes? LOVE IT!❞

❝I love to see your messages❞

❝It's okay to be happy❞

❝Our date, our love❞

❝Sen benim beşinci yıldızım, her gece gökyüzümde parlıyorsun❞

─BLOOD TO SPILL (NIKTO X EINAR)

❝Loving with madness❞ Pilot

❝The sky is not blue and the world is not pink❞ Page 1

❝Sin City❞ Page 2

─THE FLOWERS ARE FRESH AND THEIR FACES WET

❝The Death of souls❞ Page 1

❝Dreams sometimes hurt❞ Page 2

─HISTORY OF VILHJALMUR AND EIRIK

❝New life❞ The endless beginning of an eternal love

❝Happy birthday Eirik!!❞ Surprise my king!

❝Sticker❞ It is the best gift

જ⁀➴

─THE DREAMS OF VILHJALMUR

❝My inner child❞ Everything is going to happen

─HISTORY OF NIKTO AND EINAR

❝Between life and death❞ One Star Relapses

❝University days❞ (1/?) The reality of this couple at university

❝Football game❞ I invite you to watch the soccer game with me

❝Memories in Melody❞ Our first song ˚ ༘♡ ·˚ ₊˚ˑ༄ؘ

Ko-fi Each donation will receive a doodle if it is from the COD or if you specify it to me!! ˙ ͜ʟ˙

──────────≫•◦ ❈ ◦.

Oc's

.◦ ❈ ◦•≪ ──────────

Death

Life

Dennyx

Marshall

Fresita

Einar

Skaperen

Tetnig

Andy ( Comic 1 )

Koer

Vilhjalmur

Eirik

Ezz

Ariad

║▌│█║▌│ █║▌│█│║▌║

Over time I am updating and publishing all the comics I made ☝️😌

In my profile you have the option to ask me questions in case you want to ask me questions about me or about the comics.

tags:

#my art#cod#call of duty#ocs#fusion#konig cod#krueger cod#cod nikto#cod einar#vilhjalmur cod#eirik cod#cod au#vilhjalmur x eirik#nikto x einar

1 note

·

View note

Note

what do you think of the whole actor in shrine situation? is this why you're moving away from s/h//l?

lol

A medieval fisherman is said to have hauled up a three-foot-long cod, which was common enough at the time. And the fact that the cod could talk was not especially surprising. But what was astonishing was that it spoke an unknown language. It spoke Basque.

This Basque folktale shows not only the Basque attachment to their orphan language, indecipherable to the rest of the world, but also their tie to the Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua, a fish that has never been found in Basque or even Spanish waters.

The Basques are enigmatic. They have lived in what is now the northwest corner of Spain and a nick of the French southwest for longer than history records, and not only is the origin of their language unknown, but the origin of the people themselves remains a mystery also. According to one theory, these rosy-cheeked, dark-haired, long-nosed people were the original Iberians, driven by invaders to this mountainous corner between the Pyrenees, the Cantabrian Sierra, and the Bay of Biscay. Or they may be indigenous to this area.

They graze sheep on impossibly steep, green slopes of mountains that are thrilling in their rare, rugged beauty. They sing their own songs and write their own literature in their own language, Euskera. Possibly Europe’s oldest living language, Euskera is one of only four European languages—along with Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian—not in the Indo-European family. They also have their own sports, most notably jai alai, and even their own hat, the Basque beret, which is bigger than any other beret.

Though their lands currently reside in three provinces of France and four of Spain, Basques have always insisted that they have a country, and they call it Euskadi. All the powerful peoples around them—the Celts and Romans, the royal houses of Aquitaine, Navarra, Aragon, and Castile; later Spanish and French monarchies, dictatorships, and republics—have tried to subdue and assimilate them, and all have failed. In the 1960s, at a time when their ancient language was only whispered, having been outlawed by the dictator Francisco Franco, they secretly modernized it to broaden its usage, and today, with only 800,000 Basque speakers in the world, almost 1,000 titles a year are published in Euskera, nearly a third by Basque writers and the rest translations.

“Nire aitaren etxea / defendituko dut. / Otsoen kontra” (I will defend / the house of my father. / Against the wolves) are the opening lines of a famous poem in modern Euskera by Gabriel Aresti, one of the fathers of the modernized tongue. Basques have been able to maintain this stubborn independence, despite repression and wars, because they have managed to preserve a strong economy throughout the centuries. Not only are Basques shepherds, but they are also a seafaring people, noted for their successes in commerce. During the Middle Ages, when Europeans ate great quantities of whale meat, the Basques traveled to distant unknown waters and brought back whale. They were able to travel such distances because they had found huge schools of cod and salted their catch, giving them a nutritious food supply that would not spoil on long voyages.

Basques were not the first to cure cod. Centuries earlier, the Vikings had traveled from Norway to Iceland to Greenland to Canada, and it is not a coincidence that this is the exact range of the Atlantic cod. In the tenth century, Thorwald and his wayward son, Erik the Red, having been thrown out of Norway for murder, traveled to Iceland, where they killed more people and were again expelled. About the year 985, they put to sea from the black lava shore of Iceland with a small crew on a little open ship. Even in midsummer, when the days are almost without nightfall, the sea there is gray and kicks up whitecaps. But with sails and oars, the small band made it to a land of glaciers and rocks, where the water was treacherous with icebergs that glowed robin’s-egg blue. In the spring and summer, chunks broke off the glaciers, crashed into the sea with a sound like thunder that echoed in the fjords, and sent out huge waves. Eirik, hoping to colonize this land, tried to enhance its appeal by naming it Greenland.

Almost 1,000 years later, New England whalers would sing: “Oh, Greenland is a barren place / a place that bears no green / Where there’s ice and snow / and the whale fishes blow / But daylight’s seldom seen.”

Eirik colonized this inhospitable land and then tried to push on to new discoveries. But he injured his foot and had to be left behind. His son, Leifur, later known as Leif Eiriksson, sailed on to a place he called Stoneland, which was probably the rocky, barren Labrador coast. “I saw not one cartload of earth, though I landed many places,” Jacques Cartier would write of this coast six centuries later. From there, Leif’s men turned south to “Woodland” and then “Vineland.” The identity of these places is not certain. Woodland could have been Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, or Maine, all three of which are wooded. But in Vineland they found wild grapes, which no one else has discovered in any of these places.

The remains of a Viking camp have been found in Newfoundland. It is perhaps in that gentler land that the Vikings were greeted by inhabitants they found so violent and hostile that they deemed settlement impossible, a striking assessment to come from a people who had been regularly banished for the habit of murdering people. More than 500 years later the Beothuk tribe of Newfoundland would prevent John Cabot from exploring beyond crossbow range of his ship. The Beothuk apparently did not misjudge Europeans, since soon after Cabot, they were enslaved by the Portuguese, driven inland, hunted by the French and English, and exterminated in a matter of decades.

How did the Vikings survive in greenless Greenland and earthless Stoneland? How did they have enough provisions to push on to Woodland and Vineland, where they dared not go inland to gather food, and yet they still had enough food to get back? What did these Norsemen eat on the five expeditions to America between 985 and 1011 that have been recorded in the Icelandic sagas? They were able to travel to all these distant, barren shores because they had learned to preserve codfish by hanging it in the frosty winter air until it lost four-fifths of its weight and became a durable woodlike plank. They could break off pieces and chew them, eating it like hardtack. Even earlier than Eirik’s day, in the ninth century, Norsemen had already established plants for processing dried cod in Iceland and Norway and were trading the surplus in northern Europe.

The Basques, unlike the Vikings, had salt, and because fish that was salted before drying lasted longer, the Basques could travel even farther than the Vikings. They had another advantage: The more durable a product, the easier it is to trade. By the year 1000, the Basques had greatly expanded the cod markets to a truly international trade that reached far from the cod’s northern habitat.

In the Mediterranean world, where there were not only salt deposits but a strong enough sun to dry sea salt, salting to preserve food was not a new idea. In preclassical times, Egyptians and Romans had salted fish and developed a thriving trade. Salted meats were popular, and Roman Gaul had been famous for salted and smoked hams. Before they turned to cod, the Basques had sometimes salted whale meat; salt whale was found to be good with peas, and the most prized part of the whale, the tongue, was also often salted.

Until the twentieth-century refrigerator, spoiled food had been a chronic curse and severely limited trade in many products, especially fish. When the Basque whalers applied to cod the salting techniques they were using on whale, they discovered a particularly good marriage because the cod is virtually without fat, and so if salted and dried well, would rarely spoil. It would outlast whale, which is red meat, and it would outlast herring, a fatty fish that became a popular salted item of the northern countries in the Middle Ages.

Even dried salted cod will turn if kept long enough in hot humid weather. But for the Middle Ages it was remarkably long-lasting—a miracle comparable to the discovery of the fast-freezing process in the twentieth century, which also debuted with cod. Not only did cod last longer than other salted fish, but it tasted better too. Once dried or salted—or both—and then properly restored through soaking, this fish presents a flaky flesh that to many tastes, even in the modern age of refrigeration, is far superior to the bland white meat of fresh cod. For the poor who could rarely afford fresh fish, it was cheap, high-quality nutrition.

In 1606, Gudbrandur Thorláksson, an Icelandic bishop, made this line drawing of the North Atlantic in which Greenland is represented in the shape of a dragon with a fierce, toothy mouth. Modern maps show that this is not at all the shape of Greenland, but it is exactly what it looks like from the southern fjords, which cut jagged gashes miles deep into the high mountains. (Royal Library, Copenhagen)

Catholicism gave the Basques their great opportunity. The medieval church imposed fast days on which sexual intercourse and the eating of flesh were forbidden, but eating “cold” foods was permitted. Because fish came from water, it was deemed cold, as were waterfowl and whale, but meat was considered hot food. The Basques were already selling whale meat to Catholics on “lean days,” which, since Friday was the day of Christ’s crucifixion, included all Fridays, the forty days of Lent, and various other days of note on the religious calendar. In total, meat was forbidden for almost half the days of the year, and those lean days eventually became salt cod days. Cod became almost a religious icon—a mythological crusader for Christian observance.

The Basques were getting richer every Friday. But where was all this cod coming from? The Basques, who had never even said where they came from, kept their secret. By the fifteenth century, this was no longer easy to do, because cod had become widely recognized as a highly profitable commodity and commercial interests around Europe were looking for new cod grounds. There were cod off of Iceland and in the North Sea, but the Scandinavians, who had been fishing cod in those waters for thousands of years, had not seen the Basques. The British, who had been fishing for cod well offshore since Roman times, did not run across Basque fishermen even in the fourteenth century, when British fishermen began venturing up to Icelandic waters. The Bretons, who tried to follow the Basques, began talking of a land across the sea.

Bench ends from St. Nicolas’ Chapel in a town by the North Sea, King’s Lynn, Norfolk, England, carved circa 1415, depict the cod fishery. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

In the 1480s, a conflict was brewing between Bristol merchants and the Hanseatic League. The league had been formed in thirteenth-century Lübeck to regulate trade and stand up for the interests of the merchant class in northern German towns. Hanse means “fellowship” in Middle High German. This fellowship organized town by town and spread throughout northern Europe, including London. By controlling the mouths of all the major rivers that ran north from central Europe, from the Rhine to the Vistula, the league was able to control much of European trade and especially Baltic trade. By the fourteenth century, it had chapters as far north as Iceland, as far east as Riga, south to the Ukraine, and west to Venice.

For many years, the league was seen as a positive force in northern Europe. It stood up against the abuses of monarchs, stopped piracy, dredged channels, and built lighthouses. In England, league members were called Easterlings because they came from the east, and their good reputation is reflected in the word sterling, which comes from Easterling and means “of assured value.”

But the league grew increasingly abusive of its power and ruthless in defense of trade monopolies. In 1381, mobs rose up in England and hunted down Hanseatics, killing anyone who could not say bread and cheese with an English accent.

The Hanseatics monopolized the Baltic herring trade and in the fifteenth century attempted to do the same with dried cod. By then, dried cod had become an important product in Bristol. Bristol’s well-protected but difficult-to-navigate harbor had greatly expanded as a trade center because of its location between Iceland and the Mediterranean. It had become a leading port for dried cod from Iceland and wine, especially sherry, from Spain. But in 1475, the Hanseatic League cut off Bristol merchants from buying Icelandic cod.

Thomas Croft, a wealthy Bristol customs official, trying to find a new source of cod, went into partnership with John Jay, a Bristol merchant who had what was at the time a Bristol obsession: He believed that somewhere in the Atlantic was an island called Hy-Brasil. In 1480, Jay sent his first ship in search of this island, which he hoped would offer a new fishing base for cod. In 1481, Jay and Croft outfitted two more ships, the Trinity and the George. No record exists of the result of this enterprise. Croft and Jay were as silent as the Basques. They made no announcement of the discovery of Hy-Brasil, and history has written off the voyage as a failure. But they did find enough cod so that in 1490, when the Hanseatic League offered to negotiate to reopen the Iceland trade, Croft and Jay simply weren’t interested anymore.

Where was their cod coming from? It arrived in Bristol dried, and drying cannot be done on a ship deck. Since their ships sailed out of the Bristol Channel and traveled far west of Ireland and there was no land for drying fish west of Ireland—Jay had still not found Hy-Brasil—it was suppposed that Croft and Jay were buying the fish somewhere. Since it was illegal for a customs official to engage in foreign trade, Croft was prosecuted. Claiming that he had gotten the cod far out in the Atlantic, he was acquitted without any secrets being revealed.

To the glee of the British press, a letter has recently been discovered. The letter had been sent to Christopher Columbus, a decade after the Croft affair in Bristol, while Columbus was taking bows for his discovery of America. The letter, from Bristol merchants, alleged that he knew perfectly well that they had been to America already. It is not known if Columbus ever replied. He didn’t need to. Fishermen were keeping their secrets, while explorers were telling the world. Columbus had claimed the entire new world for Spain.

Then, in 1497, five years after Columbus first stumbled across the Caribbean while searching for a westward route to the spice-producing lands of Asia, Giovanni Caboto sailed from Bristol, not in search of the Bristol secret but in the hopes of finding the route to Asia that Columbus had missed. Caboto was a Genovese who is remembered by the English name John Cabot, because he undertook this voyage for Henry VII of England. The English, being in the North, were far from the spice route and so paid exceptionally high prices for spices. Cabot reasoned correctly that the British Crown and the Bristol merchants would be willing to finance a search for a northern spice route. In June, after only thirty-five days at sea, Cabot found land, though it wasn’t Asia. It was a vast, rocky coastline that was ideal for salting and drying fish, by a sea that was teeming with cod. Cabot reported on the cod as evidence of the wealth of this new land,

New Found Land, which he claimed for England. Thirty-seven years later, Jacques Cartier arrived, was credited with “discovering” the mouth of the St. Lawrence, planted a cross on the Gaspé Peninsula, and claimed it all for France. He also noted the presence of 1,000 Basque fishing vessels. But the Basques, wanting to keep a good secret, had never claimed it for anyone.

17 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hillary Clinton visited Norway last week, an event that brought to my mind, anyway, the fact that, adjusting for population, no country has been more generous to her family’s stupendously sordid con operation than has the land of the fjords. The numbers are scandalous. Between 2007 and 2016, the Norwegian government transferred no less than 640 million kroner in taxpayer money to the Clinton Foundation. Given the average exchange rate during that period, that sum would’ve been roughly equivalent to $100 million. This means that each and every Norwegian citizen, without being asked, put about twenty dollars into the pockets of that crooked enterprise. The official reason for these massive payouts was that the Norwegian government wanted to help mothers and children in Africa. In 2016, Norway’s purported newspaper of record, Aftenposten, ran an article in which Stephen Gillers, an expert on legal ethics at NYU, said that the real motive was to buy influence for Norway in the corridors of American power. Well, that’s one reason, but there are others. One is this: Top-level Norwegian politicians are as ambitious as politicians anywhere. For many of them, becoming a member of parliament or cabinet official or even prime minister in a country of six million people isn’t quite enough to satisfy the old ego. How to solve this problem? Fortunately, a solution is already in place. Norway has long paid a hell of a lot more into major world organizations, from the UN on down, than other countries of its size. In fact, it spends more per capita on international development than any nation on Earth. Yes, this means that Norwegian citizens are getting ripped off. On the other hand, it also means that Norwegian political leaders have a terrific leg up when it comes to getting cushy sinecures at international bodies, especially those purportedly dedicated to humanitarian aid. So it is that former Prime Minister Thorbjørn Jagland is now secretary general of the Council of Europe. Gro Harlem Brundtland, another ex-PM, went on to become director-general of the World Health Organization. Jan Egeland left a top post in the Norwegian Foreign Ministry to become the head UN guy for humanitarian affairs and emergency relief. The attractiveness of the Clinton Foundation as a place to throw hard-working Norwegians’ dough at can be explained by the fact that, during the years when those payouts were taking place, Hillary was, in turn, a U.S. senator and leading presidential candidate, the U.S. secretary of State, and, again, a leading presidential candidate. To funnel cash to her was to buy a personal “in” with the most powerful woman on Earth. Not to mention that Norwegian politicians have always had a thing for the Clintons. Bill and Hillary always did a good job of presenting themselves as the kind of American politicians that they can relate to -- you know, loads of lofty talk about international interdependence and common humanity and standing up for the marginalized and how women’s rights are human rights and how it takes a village to raise a child. Still, given the findings set out in Peter Schweizer’s 2015 book and 2016 documentary Clinton Cash -- which revealed in excruciating detail that the Clinton Foundation was little more than a sleazy money-making operation for a couple of shameless grifters whose avarice apparently knows no bounds -- you’d think that the Norwegian bigwigs who’d handed over all those kroner to Bill and Hill would feel like fools, dupes, patsies, saps, suckers. You’d think they’d be leading the chorus of “Lock her up!” Nope. Last Friday -- International Women’s Day -- she was invited to a cozy family dinner at the home of Jonas Gahr Støre, Norway’s current Labour Party leader, who served as foreign minister at the same time that Hillary was secretary of State. VG, Norway’s largest paper, covered the evening’s repast as a charming reunion between old pals. In his not quite hard-hitting account, reporter Eirik Mosveen focused on a fan letter that was written to Hillary by three 14-year-old Oslo girls that deputy party leader Hadia Tajik handed to her over dinner. The girls appear to have been brainwashed into thinking that Hillary is a heroine of the #MeToo movement, and Mosveen, instead of reminding readers that this is the woman who tried her best to destroy Monica Lewinsky and other victims of her rapist husband, went along with this pretty fiction. In an interview with Tajik about the dinner (they had cod and wine), the closest Mosveen apparently came to asking a tough question was this: “Did she have any good jokes about Donald Trump?” No surprise there. In the Norwegian news media, as in their American counterparts, Trump -- who in January of last year famously paid the nation a fine compliment by wondering why the U.S. can’t take fewer immigrants from “shithole countries” and more from places like Norway -- is always the joke, the clown, the bad guy, while the Clintons, even though they royally bilked the Norwegian public, still get the royal treatment. I suppose Gahr Støre, who plans to be Norway’s next prime minister, feels that the chances of Hillary becoming president, while looking pretty slim at the moment, are sizable enough to make it worth his while to have her over for supper. After all, he and his cronies already made her and Bill $100 million richer at the expense of Norway’s deplorables. Compared to that, what’s the cost of another meal? Who knows, she may yet be in a position to give a career boost to Gahr Støre -- and Tajik, too -- once their time at the top of the Norwegian heap is over.

0 notes

Text

18 Norwegian foods you’ve probably never heard of

(CNN)“We have products, history here that you don’t find anywhere else in the world,” says Esben Holmboe Bang, the Danish head chef of Oslo’s three-Michelin-starred restaurant Maaemo.

“For me it was mind-blowing. I saw the way they preserved fish, meat and I just thought I’ve never seen this before.”

Norway’s distinctive cuisine has been shaped by its 100,000-kilometer coastline, by its long winters and brief summers, by the forests that cover a third of its surface, and by the mountains that cut west off from east.

Here are 18 of Norway’s greatest — and strangest — specialties.

MORE: Norway becomes first country to ban deforestation

1. Smalahove

“You have to try it once in your life. This is amazing thing,” says Eirik Braek, owner of Oslo deli Fenaknoken, holding up a whole sheep’s head.

Fenaknoken is an Aladdin’s cave of cured, dried and salted delicacies, with hams strung from the ceiling like chandeliers, and Braek is a charming and enthusiastic host, giving all visitors to his shop a tasting tour of Norwegian food history.

Smalahove — literally sheep’s head — is a Christmas treat in Western Norway.

“You start with the eyes,” says Braek, because the fatty areas taste better warm. “This one you have to serve hot.”

2. Great Scallop

JUST WATCHED

Part 2: In search of the Great Scallop

Replay

More Videos …

MUST WATCH

“The sea is something we live off now and it’s something that we lived on for centuries,” says Holmboe Bang. “There’s a strong belonging to the sea.”

The cold waters mean seafood takes longer to grow, making the flesh is extra plump and tender.

In the Norway episode of “Culinary Journeys,” Holmboe Bang and Maaemo’s diver Roderick Sloan feast on “salty, intensely sweet” Great Scallops, served in their shell with reindeer moss and juniper.

People love fish so much, says Braek, that they’ll drink Omega 3 at Christmas to line their stomachs pre-revelry: “Just a small scoop. You can have more alcohol, maybe.”

MORE: Culinary theater at the world’s most northerly Michelin-starred restaurant

3. Mahogany clam

The world’s oldest animal ever is said to be a sprightly little bivalve mollusk by the name of Ming, who was dredged off the coast of Iceland in 2006 and estimated to be 507 years old.

The ones found off Norway’s northern coast will usually have been chilling in the Arctic depths for 150 to 200 years.

Says Roderick Sloan: “My job is like going to the moon every day.

“When I’m on the bottom, I only have two sounds: the sound of my heart and the sound of my breath.”

4. Dried everything

“In Norway we dry everything, because we have to,” says Braek. “We did this to survive in the future. We salted and dried things.”

Holmboe Bang agrees.

Fermenting, pickling, salting, curing, smoking: “It’s all about trying to prolong summer, it’s about making the taste of summer last.

“We’ve developed these intensely special, completely different flavor profile than the produce has in the summer, but that’s for us the taste of winter.”

“People did this for thousands of years,” he adds.

“When you think about the way people had to survive, you had to preserve your fish, you had to think ‘I have to stock up my larder for the winter, otherwise me and my family are going to die’… We don’t have that mentality any more.

“I feel like now we live in a society where everything is available all the time, and that’s a blessing and a curse.”

5. Klippfisk

JUST WATCHED

Part 3: A celebration of Nordic hospitality

Replay

More Videos …

MUST WATCH

Klippfisk — literally “cliff fish” — is dried and salted cod, in a tradition dating back to the 17th century.

In the “Culinary Journeys” video above, Holmboe Bang is schooled in the method by Nordskot expert Erling Heckneby.

6. Cod tongues

The season for fresh fish is January to April, says Braek.

Skrei — or cod — is one of Norway’s greatest exports but one specialty that hasn’t been such a hit abroad is cod tongue.

The cut is less the actual tongue than the underside of the cod chin, should you find “cod chin” sounds more appealing.

The best way to wrap your lips round some cod tongue is to toss them in seasoned flour and fry them in butter.

7. Gamalost

Gamalost means “old cheese” — and this is one that was actually eaten by Vikings.

It’s a hard, crumbly brownish-yellow cheese with a sharp, intense flavor and a pungent scent to match.

“Some people love it, some people hate it,” says Braek.

Those who really love it can join the annual Gamalost Festival held in Vik in May.

“This cheese we can keep forever. This never gets old,” adds Braek, explaining that it was a Norwegian staple in the days before refrigeration.

Production is very labor-intensive, so it’s rare to find gamalost for sale outside Norway.

MORE: Best country in the world to live? Still Norway, according to the U.N.

8. Brunost

Much easier to find than gamalost, brunost is the sweet-savory brown cheese that delights Norwegians and surprises foreigners.

It’s a goat’s cheese made from caramelized whey — giving it a sharp, sweet-sour dulce de leche taste — and its fat and sugar content is such that a truck of the stuff burnt for five days when it caught fire in a Norwegian tunnel in 2013.

Norwegians eat it on toast, with crispbread, with jam and at breakfast — though any meal will do.

A classic combo is sliced brunost on top of one of Norway’s sweetly heart-shaped waffles. They’re softer and more pliable than the Belgian variety, making them easier to fold in the hand.

At Christmas they’re eaten on toasted buttered julecake — a festive cake flavored with cardamom and dotted with fruit and candied peel.

9. Reindeer and elk

Forget the Pepsi Challenge — visitors to Fenaknoken can sample dried elk and dried reindeer side by side.

“Elk is like a dry, more wild taste,” says Braek. Reindeer is a “much smaller animal so it’s much sweeter.”

Reindeer moss — so called because reindeer eat it — is a lichen found in Arctic tundra. “It’s very special to Norway,” explains Sloan. “This is where the reindeer get all their flavor from.”

It’s also sometimes used in the making of akvavit, the famous Scandinavian spirit.

MORE: The Dukha: Last of Mongolia’s reindeer people

10. Farikal

“This is a map of Norway,” explains Braek, holding a vacuum-packed leg of lamb and pointing out the west coast, where cuisine was influenced by the shipping trade and mixing cultures, and the isolated mountain-bound east.

“At Christmas I have about 1.5 tonnes of lamb ribs” hanging from the roof of the shop, he says, a welcome sight for homesick Norwegians returning home for the festive season.

“I have people stand here and cry. ‘I’m home!’”

Pinnejott — “stick meat” — is a festive dish of salted and dried lamb or mutton ribs, typical to the west and north.

The national dish, however is farikal, a lamb and cabbage casserole traditionally eaten in fall.

11. Cloudberries

Norway has a Willy Wonka-esque inventory of evocative berry names: cloudberries, crowberries … but sadly no snozzberries.

The ethereal cloudberry is golden-yellow and only found in the wild. Its rarity earns it the nickname Arctic gold.

They have a tart appleish flavor and are often made into jam. “If you find any, don’t tell anyone where you find them,” says Braek.

Crowberry is a black cold-climate berry found in northern Europe, Alaska, Canada, Greenland and beyond.

12. Lutefisk

If a gelatinous mix of dried fish and lye doesn’t sound appealing, you might not be alone.

When we visited the world’s only Lutefisk Museum, in Norway’s “Christmas town” of Drobok, on a sunny day in May the entire place was empty — a piscine Marie Celeste with no staff, no customers, but one forlorn pile of children’s letters to Santa.

Lutefisk is a festive specialty, made by air-drying fish, reconstituting it by soaking it in cold water for a week, then soaking it in caustic lye soda for two days.

Then, to get rid of the poisonous lye, it’s soaked in water for another couple of days.

It’s not eaten in the summertime, but out of season visitors can console themselves with a light and frothy fiskesuppe (fish soup) in the cherry blossom-shaded courtyard of the Skipperstuen restaurant opposite the Museum and Aquarium, overlooking the Oslofjord.

13. Salty liquorice

Yes, the Norwegians like salting everything so much, they even do it to their candy.

The controversial mouth-puckering treat is wildly popular in the Nordic countries and widely reviled elsewhere.

It’s an acquired taste, but if you like your aniseed strong, and your gustatory receptors tingling in tandem, it might just be the candy for you.

14. Torrfisk

Torrfisk, or stockfish, is unsalted air-dried fish, usually cod.

It’s been “made in Norway for, people say, about 1,000 years,” says Braek.

It’s mentioned in the 13th century Icelandic work “Egil’s Saga,” when a chieftain ships stockfish from Norway to Britain in 875 AD.

As such, it was Norway’s biggest export for centuries.

15. Rakfisk

Rakfisk is salted, fermented trout, and it packs a pungent — and delicious — punch.

It’s usually fermented for two to three months, but it can be up to a year.

It’s often eaten with flatbrod (Norwegian flat bread) or lefse (potato bread), onions and sour cream.

16. King Crab

Like the sound of a King Crab safari?

A number of tour operators offer trips to Kirkenes, on the border with Russia, to hunt the Arctic King Crab between the months of December and April.

The mighty crustaceans can grow to a leg span of 1.8 meters.

17. Seagull eggs

Seagulls are arguably the most thuggish of seabirds, raised — in the UK, at least — on a diet of ketchup, French fries and stolen sandwiches.

But in late April or early May in northern Norway, locals like to eat hard-boiled seagulls’ eggs washed down with a pilsner beer from Tromso’s Mack’s brewery.

We don’t recommend you attempt to harvest any yourself — to protect the species, but also to protect yourself. Those gulls can be pretty handy when it comes to a fight.

18. Whale

Norway is one of only three countries still involved in the controversial practice of whaling, alongside Japan and Iceland.

For those who can stomach it, whale meat — or hvalkjott — is widely available and often marketed at curious tourists.

“I’ve tried whale and reindeer,” says Jen, a Canadian on a one-woman tour of Norway.

“Whale’s really good. I’m from the east coast, so we have a lot of fish but we don’t do whaling.”

As whales are mammals rather than fish, the taste is similar to a gamey meat such as venison.

Source: http://allofbeer.com/2017/05/27/18-norwegian-foods-youve-probably-never-heard-of/

from All of Beer https://allofbeer.wordpress.com/2017/05/27/18-norwegian-foods-youve-probably-never-heard-of/

0 notes

Text

18 Norwegian foods you’ve probably never heard of

(CNN)“We have products, history here that you don’t find anywhere else in the world,” says Esben Holmboe Bang, the Danish head chef of Oslo’s three-Michelin-starred restaurant Maaemo.

“For me it was mind-blowing. I saw the way they preserved fish, meat and I just thought I’ve never seen this before.”

Norway’s distinctive cuisine has been shaped by its 100,000-kilometer coastline, by its long winters and brief summers, by the forests that cover a third of its surface, and by the mountains that cut west off from east.

Here are 18 of Norway’s greatest — and strangest — specialties.

MORE: Norway becomes first country to ban deforestation

1. Smalahove

“You have to try it once in your life. This is amazing thing,” says Eirik Braek, owner of Oslo deli Fenaknoken, holding up a whole sheep’s head.

Fenaknoken is an Aladdin’s cave of cured, dried and salted delicacies, with hams strung from the ceiling like chandeliers, and Braek is a charming and enthusiastic host, giving all visitors to his shop a tasting tour of Norwegian food history.

Smalahove — literally sheep’s head — is a Christmas treat in Western Norway.

“You start with the eyes,” says Braek, because the fatty areas taste better warm. “This one you have to serve hot.”

2. Great Scallop

JUST WATCHED

Part 2: In search of the Great Scallop

Replay

More Videos …

MUST WATCH

“The sea is something we live off now and it’s something that we lived on for centuries,” says Holmboe Bang. “There’s a strong belonging to the sea.”

The cold waters mean seafood takes longer to grow, making the flesh is extra plump and tender.

In the Norway episode of “Culinary Journeys,” Holmboe Bang and Maaemo’s diver Roderick Sloan feast on “salty, intensely sweet” Great Scallops, served in their shell with reindeer moss and juniper.

People love fish so much, says Braek, that they’ll drink Omega 3 at Christmas to line their stomachs pre-revelry: “Just a small scoop. You can have more alcohol, maybe.”

MORE: Culinary theater at the world’s most northerly Michelin-starred restaurant

3. Mahogany clam

The world’s oldest animal ever is said to be a sprightly little bivalve mollusk by the name of Ming, who was dredged off the coast of Iceland in 2006 and estimated to be 507 years old.

The ones found off Norway’s northern coast will usually have been chilling in the Arctic depths for 150 to 200 years.

Says Roderick Sloan: “My job is like going to the moon every day.

“When I’m on the bottom, I only have two sounds: the sound of my heart and the sound of my breath.”

4. Dried everything

“In Norway we dry everything, because we have to,” says Braek. “We did this to survive in the future. We salted and dried things.”

Holmboe Bang agrees.

Fermenting, pickling, salting, curing, smoking: “It’s all about trying to prolong summer, it’s about making the taste of summer last.

“We’ve developed these intensely special, completely different flavor profile than the produce has in the summer, but that’s for us the taste of winter.”

“People did this for thousands of years,” he adds.

“When you think about the way people had to survive, you had to preserve your fish, you had to think ‘I have to stock up my larder for the winter, otherwise me and my family are going to die’… We don’t have that mentality any more.

“I feel like now we live in a society where everything is available all the time, and that’s a blessing and a curse.”

5. Klippfisk

JUST WATCHED

Part 3: A celebration of Nordic hospitality

Replay

More Videos …

MUST WATCH

Klippfisk — literally “cliff fish” — is dried and salted cod, in a tradition dating back to the 17th century.

In the “Culinary Journeys” video above, Holmboe Bang is schooled in the method by Nordskot expert Erling Heckneby.

6. Cod tongues

The season for fresh fish is January to April, says Braek.

Skrei — or cod — is one of Norway’s greatest exports but one specialty that hasn’t been such a hit abroad is cod tongue.

The cut is less the actual tongue than the underside of the cod chin, should you find “cod chin” sounds more appealing.

The best way to wrap your lips round some cod tongue is to toss them in seasoned flour and fry them in butter.

7. Gamalost

Gamalost means “old cheese” — and this is one that was actually eaten by Vikings.

It’s a hard, crumbly brownish-yellow cheese with a sharp, intense flavor and a pungent scent to match.

“Some people love it, some people hate it,” says Braek.

Those who really love it can join the annual Gamalost Festival held in Vik in May.

“This cheese we can keep forever. This never gets old,” adds Braek, explaining that it was a Norwegian staple in the days before refrigeration.

Production is very labor-intensive, so it’s rare to find gamalost for sale outside Norway.

MORE: Best country in the world to live? Still Norway, according to the U.N.

8. Brunost

Much easier to find than gamalost, brunost is the sweet-savory brown cheese that delights Norwegians and surprises foreigners.

It’s a goat’s cheese made from caramelized whey — giving it a sharp, sweet-sour dulce de leche taste — and its fat and sugar content is such that a truck of the stuff burnt for five days when it caught fire in a Norwegian tunnel in 2013.

Norwegians eat it on toast, with crispbread, with jam and at breakfast — though any meal will do.

A classic combo is sliced brunost on top of one of Norway’s sweetly heart-shaped waffles. They’re softer and more pliable than the Belgian variety, making them easier to fold in the hand.

At Christmas they’re eaten on toasted buttered julecake — a festive cake flavored with cardamom and dotted with fruit and candied peel.

9. Reindeer and elk

Forget the Pepsi Challenge — visitors to Fenaknoken can sample dried elk and dried reindeer side by side.

“Elk is like a dry, more wild taste,” says Braek. Reindeer is a “much smaller animal so it’s much sweeter.”

Reindeer moss — so called because reindeer eat it — is a lichen found in Arctic tundra. “It’s very special to Norway,” explains Sloan. “This is where the reindeer get all their flavor from.”

It’s also sometimes used in the making of akvavit, the famous Scandinavian spirit.

MORE: The Dukha: Last of Mongolia’s reindeer people

10. Farikal

“This is a map of Norway,” explains Braek, holding a vacuum-packed leg of lamb and pointing out the west coast, where cuisine was influenced by the shipping trade and mixing cultures, and the isolated mountain-bound east.

“At Christmas I have about 1.5 tonnes of lamb ribs” hanging from the roof of the shop, he says, a welcome sight for homesick Norwegians returning home for the festive season.

“I have people stand here and cry. ‘I’m home!‘”

Pinnejott — “stick meat” — is a festive dish of salted and dried lamb or mutton ribs, typical to the west and north.

The national dish, however is farikal, a lamb and cabbage casserole traditionally eaten in fall.

11. Cloudberries

Norway has a Willy Wonka-esque inventory of evocative berry names: cloudberries, crowberries … but sadly no snozzberries.

The ethereal cloudberry is golden-yellow and only found in the wild. Its rarity earns it the nickname Arctic gold.

They have a tart appleish flavor and are often made into jam. “If you find any, don’t tell anyone where you find them,” says Braek.

Crowberry is a black cold-climate berry found in northern Europe, Alaska, Canada, Greenland and beyond.

12. Lutefisk

If a gelatinous mix of dried fish and lye doesn’t sound appealing, you might not be alone.

When we visited the world’s only Lutefisk Museum, in Norway’s “Christmas town” of Drobok, on a sunny day in May the entire place was empty — a piscine Marie Celeste with no staff, no customers, but one forlorn pile of children’s letters to Santa.

Lutefisk is a festive specialty, made by air-drying fish, reconstituting it by soaking it in cold water for a week, then soaking it in caustic lye soda for two days.

Then, to get rid of the poisonous lye, it’s soaked in water for another couple of days.

It’s not eaten in the summertime, but out of season visitors can console themselves with a light and frothy fiskesuppe (fish soup) in the cherry blossom-shaded courtyard of the Skipperstuen restaurant opposite the Museum and Aquarium, overlooking the Oslofjord.

13. Salty liquorice

Yes, the Norwegians like salting everything so much, they even do it to their candy.

The controversial mouth-puckering treat is wildly popular in the Nordic countries and widely reviled elsewhere.

It’s an acquired taste, but if you like your aniseed strong, and your gustatory receptors tingling in tandem, it might just be the candy for you.

14. Torrfisk

Torrfisk, or stockfish, is unsalted air-dried fish, usually cod.

It’s been “made in Norway for, people say, about 1,000 years,” says Braek.

It’s mentioned in the 13th century Icelandic work “Egil’s Saga,” when a chieftain ships stockfish from Norway to Britain in 875 AD.

As such, it was Norway’s biggest export for centuries.

15. Rakfisk

Rakfisk is salted, fermented trout, and it packs a pungent — and delicious — punch.

It’s usually fermented for two to three months, but it can be up to a year.

It’s often eaten with flatbrod (Norwegian flat bread) or lefse (potato bread), onions and sour cream.

16. King Crab

Like the sound of a King Crab safari?

A number of tour operators offer trips to Kirkenes, on the border with Russia, to hunt the Arctic King Crab between the months of December and April.

The mighty crustaceans can grow to a leg span of 1.8 meters.

17. Seagull eggs

Seagulls are arguably the most thuggish of seabirds, raised — in the UK, at least — on a diet of ketchup, French fries and stolen sandwiches.

But in late April or early May in northern Norway, locals like to eat hard-boiled seagulls’ eggs washed down with a pilsner beer from Tromso’s Mack’s brewery.

We don’t recommend you attempt to harvest any yourself — to protect the species, but also to protect yourself. Those gulls can be pretty handy when it comes to a fight.

18. Whale

Norway is one of only three countries still involved in the controversial practice of whaling, alongside Japan and Iceland.

For those who can stomach it, whale meat — or hvalkjott — is widely available and often marketed at curious tourists.

“I’ve tried whale and reindeer,” says Jen, a Canadian on a one-woman tour of Norway.

“Whale’s really good. I’m from the east coast, so we have a lot of fish but we don’t do whaling.”

As whales are mammals rather than fish, the taste is similar to a gamey meat such as venison.

from All Of Beer http://allofbeer.com/2017/05/27/18-norwegian-foods-youve-probably-never-heard-of/ from All of Beer https://allofbeercom.tumblr.com/post/161120493437

0 notes

Text

18 Norwegian foods you’ve probably never heard of

(CNN)“We have products, history here that you don’t find anywhere else in the world,” says Esben Holmboe Bang, the Danish head chef of Oslo’s three-Michelin-starred restaurant Maaemo.

“For me it was mind-blowing. I saw the way they preserved fish, meat and I just thought I’ve never seen this before.”

Norway’s distinctive cuisine has been shaped by its 100,000-kilometer coastline, by its long winters and brief summers, by the forests that cover a third of its surface, and by the mountains that cut west off from east.

Here are 18 of Norway’s greatest — and strangest — specialties.

MORE: Norway becomes first country to ban deforestation

1. Smalahove

“You have to try it once in your life. This is amazing thing,” says Eirik Braek, owner of Oslo deli Fenaknoken, holding up a whole sheep’s head.

Fenaknoken is an Aladdin’s cave of cured, dried and salted delicacies, with hams strung from the ceiling like chandeliers, and Braek is a charming and enthusiastic host, giving all visitors to his shop a tasting tour of Norwegian food history.

Smalahove — literally sheep’s head — is a Christmas treat in Western Norway.

“You start with the eyes,” says Braek, because the fatty areas taste better warm. “This one you have to serve hot.”

2. Great Scallop

JUST WATCHED

Part 2: In search of the Great Scallop

Replay

More Videos …

MUST WATCH

“The sea is something we live off now and it’s something that we lived on for centuries,” says Holmboe Bang. “There’s a strong belonging to the sea.”

The cold waters mean seafood takes longer to grow, making the flesh is extra plump and tender.

In the Norway episode of “Culinary Journeys,” Holmboe Bang and Maaemo’s diver Roderick Sloan feast on “salty, intensely sweet” Great Scallops, served in their shell with reindeer moss and juniper.

People love fish so much, says Braek, that they’ll drink Omega 3 at Christmas to line their stomachs pre-revelry: “Just a small scoop. You can have more alcohol, maybe.”

MORE: Culinary theater at the world’s most northerly Michelin-starred restaurant

3. Mahogany clam

The world’s oldest animal ever is said to be a sprightly little bivalve mollusk by the name of Ming, who was dredged off the coast of Iceland in 2006 and estimated to be 507 years old.

The ones found off Norway’s northern coast will usually have been chilling in the Arctic depths for 150 to 200 years.

Says Roderick Sloan: “My job is like going to the moon every day.

“When I’m on the bottom, I only have two sounds: the sound of my heart and the sound of my breath.”

4. Dried everything

“In Norway we dry everything, because we have to,” says Braek. “We did this to survive in the future. We salted and dried things.”

Holmboe Bang agrees.

Fermenting, pickling, salting, curing, smoking: “It’s all about trying to prolong summer, it’s about making the taste of summer last.

“We’ve developed these intensely special, completely different flavor profile than the produce has in the summer, but that’s for us the taste of winter.”

“People did this for thousands of years,” he adds.

“When you think about the way people had to survive, you had to preserve your fish, you had to think ‘I have to stock up my larder for the winter, otherwise me and my family are going to die’… We don’t have that mentality any more.

“I feel like now we live in a society where everything is available all the time, and that’s a blessing and a curse.”

5. Klippfisk

JUST WATCHED

Part 3: A celebration of Nordic hospitality

Replay

More Videos …

MUST WATCH

Klippfisk — literally “cliff fish” — is dried and salted cod, in a tradition dating back to the 17th century.

In the “Culinary Journeys” video above, Holmboe Bang is schooled in the method by Nordskot expert Erling Heckneby.

6. Cod tongues

The season for fresh fish is January to April, says Braek.

Skrei — or cod — is one of Norway’s greatest exports but one specialty that hasn’t been such a hit abroad is cod tongue.

The cut is less the actual tongue than the underside of the cod chin, should you find “cod chin” sounds more appealing.

The best way to wrap your lips round some cod tongue is to toss them in seasoned flour and fry them in butter.

7. Gamalost

Gamalost means “old cheese” — and this is one that was actually eaten by Vikings.

It’s a hard, crumbly brownish-yellow cheese with a sharp, intense flavor and a pungent scent to match.

“Some people love it, some people hate it,” says Braek.

Those who really love it can join the annual Gamalost Festival held in Vik in May.

“This cheese we can keep forever. This never gets old,” adds Braek, explaining that it was a Norwegian staple in the days before refrigeration.

Production is very labor-intensive, so it’s rare to find gamalost for sale outside Norway.

MORE: Best country in the world to live? Still Norway, according to the U.N.

8. Brunost

Much easier to find than gamalost, brunost is the sweet-savory brown cheese that delights Norwegians and surprises foreigners.

It’s a goat’s cheese made from caramelized whey — giving it a sharp, sweet-sour dulce de leche taste — and its fat and sugar content is such that a truck of the stuff burnt for five days when it caught fire in a Norwegian tunnel in 2013.

Norwegians eat it on toast, with crispbread, with jam and at breakfast — though any meal will do.

A classic combo is sliced brunost on top of one of Norway’s sweetly heart-shaped waffles. They’re softer and more pliable than the Belgian variety, making them easier to fold in the hand.

At Christmas they’re eaten on toasted buttered julecake — a festive cake flavored with cardamom and dotted with fruit and candied peel.

9. Reindeer and elk

Forget the Pepsi Challenge — visitors to Fenaknoken can sample dried elk and dried reindeer side by side.

“Elk is like a dry, more wild taste,” says Braek. Reindeer is a “much smaller animal so it’s much sweeter.”

Reindeer moss — so called because reindeer eat it — is a lichen found in Arctic tundra. “It’s very special to Norway,” explains Sloan. “This is where the reindeer get all their flavor from.”

It’s also sometimes used in the making of akvavit, the famous Scandinavian spirit.

MORE: The Dukha: Last of Mongolia’s reindeer people

10. Farikal

“This is a map of Norway,” explains Braek, holding a vacuum-packed leg of lamb and pointing out the west coast, where cuisine was influenced by the shipping trade and mixing cultures, and the isolated mountain-bound east.

“At Christmas I have about 1.5 tonnes of lamb ribs” hanging from the roof of the shop, he says, a welcome sight for homesick Norwegians returning home for the festive season.

“I have people stand here and cry. ‘I’m home!'”

Pinnejott — “stick meat” — is a festive dish of salted and dried lamb or mutton ribs, typical to the west and north.

The national dish, however is farikal, a lamb and cabbage casserole traditionally eaten in fall.

11. Cloudberries

Norway has a Willy Wonka-esque inventory of evocative berry names: cloudberries, crowberries … but sadly no snozzberries.

The ethereal cloudberry is golden-yellow and only found in the wild. Its rarity earns it the nickname Arctic gold.

They have a tart appleish flavor and are often made into jam. “If you find any, don’t tell anyone where you find them,” says Braek.

Crowberry is a black cold-climate berry found in northern Europe, Alaska, Canada, Greenland and beyond.

12. Lutefisk

If a gelatinous mix of dried fish and lye doesn’t sound appealing, you might not be alone.

When we visited the world’s only Lutefisk Museum, in Norway’s “Christmas town” of Drobok, on a sunny day in May the entire place was empty — a piscine Marie Celeste with no staff, no customers, but one forlorn pile of children’s letters to Santa.

Lutefisk is a festive specialty, made by air-drying fish, reconstituting it by soaking it in cold water for a week, then soaking it in caustic lye soda for two days.

Then, to get rid of the poisonous lye, it’s soaked in water for another couple of days.

It’s not eaten in the summertime, but out of season visitors can console themselves with a light and frothy fiskesuppe (fish soup) in the cherry blossom-shaded courtyard of the Skipperstuen restaurant opposite the Museum and Aquarium, overlooking the Oslofjord.

13. Salty liquorice

Yes, the Norwegians like salting everything so much, they even do it to their candy.

The controversial mouth-puckering treat is wildly popular in the Nordic countries and widely reviled elsewhere.

It’s an acquired taste, but if you like your aniseed strong, and your gustatory receptors tingling in tandem, it might just be the candy for you.

14. Torrfisk

Torrfisk, or stockfish, is unsalted air-dried fish, usually cod.

It’s been “made in Norway for, people say, about 1,000 years,” says Braek.

It’s mentioned in the 13th century Icelandic work “Egil’s Saga,” when a chieftain ships stockfish from Norway to Britain in 875 AD.

As such, it was Norway’s biggest export for centuries.

15. Rakfisk

Rakfisk is salted, fermented trout, and it packs a pungent — and delicious — punch.

It’s usually fermented for two to three months, but it can be up to a year.

It’s often eaten with flatbrod (Norwegian flat bread) or lefse (potato bread), onions and sour cream.

16. King Crab

Like the sound of a King Crab safari?

A number of tour operators offer trips to Kirkenes, on the border with Russia, to hunt the Arctic King Crab between the months of December and April.

The mighty crustaceans can grow to a leg span of 1.8 meters.

17. Seagull eggs

Seagulls are arguably the most thuggish of seabirds, raised — in the UK, at least — on a diet of ketchup, French fries and stolen sandwiches.

But in late April or early May in northern Norway, locals like to eat hard-boiled seagulls’ eggs washed down with a pilsner beer from Tromso’s Mack’s brewery.

We don’t recommend you attempt to harvest any yourself — to protect the species, but also to protect yourself. Those gulls can be pretty handy when it comes to a fight.

18. Whale

Norway is one of only three countries still involved in the controversial practice of whaling, alongside Japan and Iceland.

For those who can stomach it, whale meat — or hvalkjott — is widely available and often marketed at curious tourists.

“I’ve tried whale and reindeer,” says Jen, a Canadian on a one-woman tour of Norway.

“Whale’s really good. I’m from the east coast, so we have a lot of fish but we don’t do whaling.”

As whales are mammals rather than fish, the taste is similar to a gamey meat such as venison.

from All Of Beer http://allofbeer.com/2017/05/27/18-norwegian-foods-youve-probably-never-heard-of/

0 notes

Text

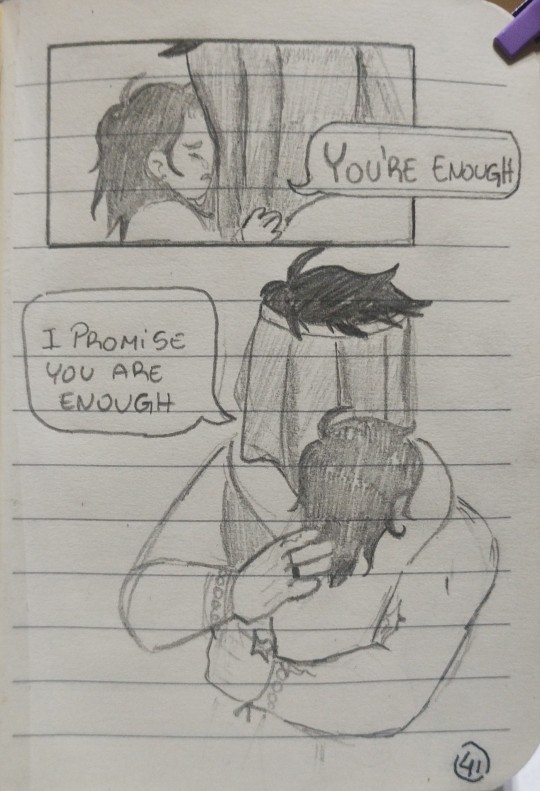

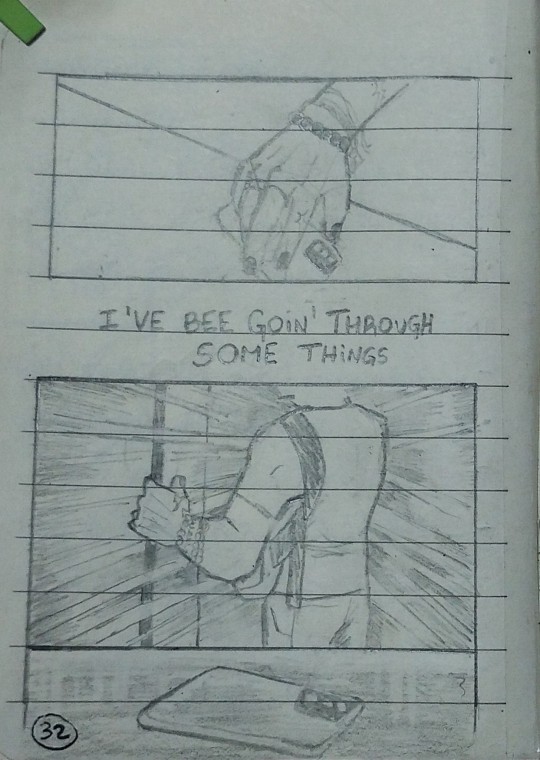

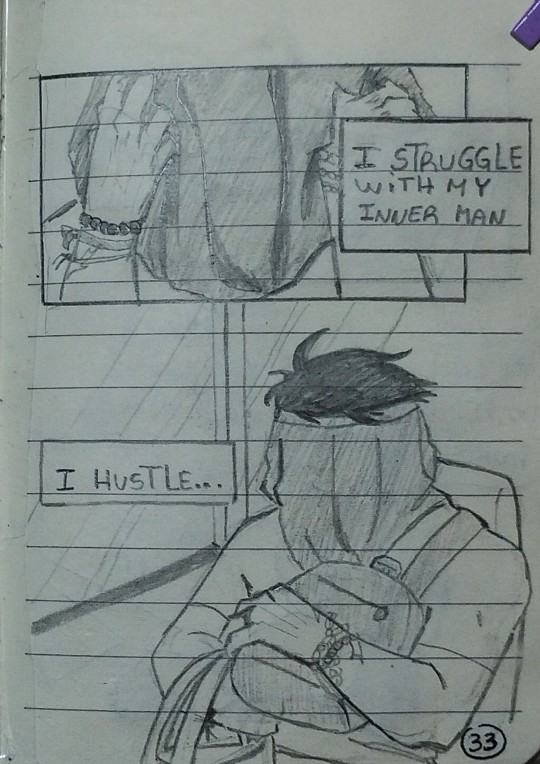

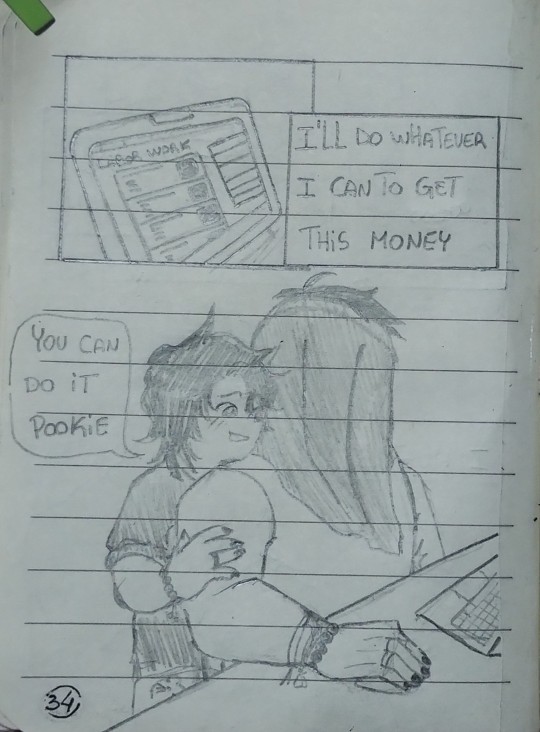

The big guy still protects his inner child for memories that sometimes he doesn't want to remember.

His inner child always cries so the big guy gives him all the confidence that he really can and tells him some words so that the little one doesn't give up.

He does this every time he sees his inner child sad in his dreams.

#my art#cod#call of duty#ocs#fusion#konig cod#krueger cod#cod nikto#cod au#vilhjalmur cod#vilhjalmur x eirik

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am going to make a kind of publication that I am going to post in the profile with the Lore of the well-ordered comics of Vilhjalmur and Eirik, so that you understand.

Why I want to separate the canonical from the non-canonical. And that pinned post will be updated every time another panel of the comic is posted. 😌☝️

#wip#art wip#my art#cod#call of duty#ocs#fusion#konig cod#krueger cod#nikto cod#cod au#Vilhjalmur x Eirik

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

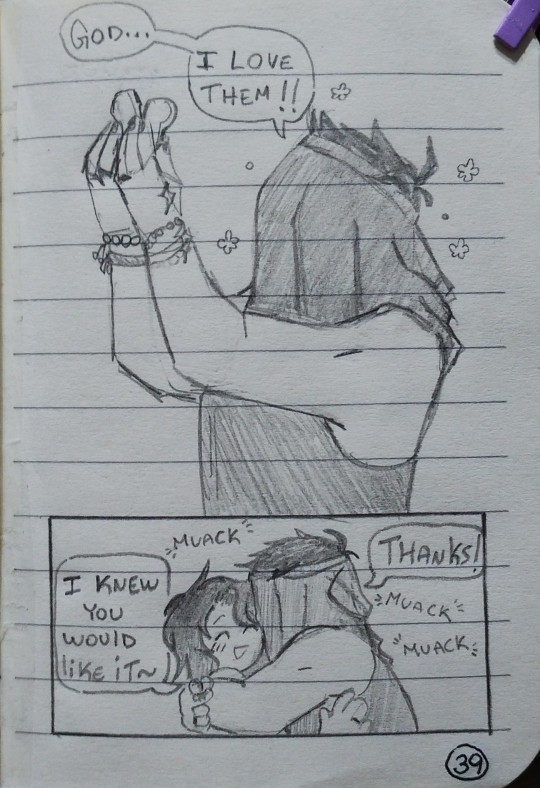

Eirik is always making things for his work and showing them to Vilhjalmur, but this time he gave him a small but meaningful gift of stickers about the big guy's favorite characters. The big guy always shows her how happy he is to see what her boyfriend likes to do at work and all the time with nice words he lets her know.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

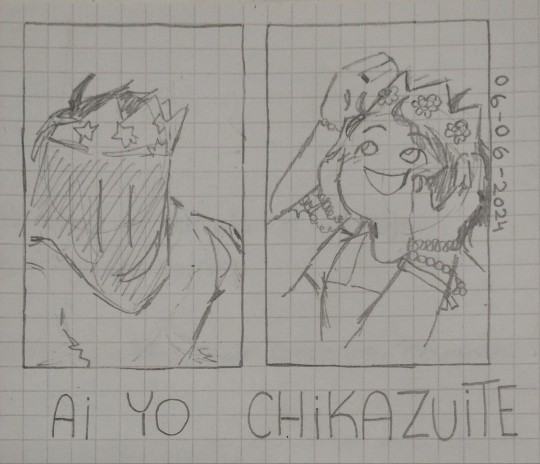

Vilhjalmur wanted to give Eirik a special gift and always thought about making him a crown like those of kings. "Love, come closer" As soon as Eirik woke up, he was impressed and his excitement was evident on his face when Vilhjalmur placed the lovingly made crown on him. What no one knew was that the big guy would kill to see that smile every day…it was a promise…and today, seeing that smile, he was fulfilling it.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vilhjalmur wanted to change his life and he did, but this adventure is just beginning… He knew it was going to be difficult to start from scratch, but he had to adapt to the new. At first he felt alone, however, it was a mature decision by the big guy. Although he always had the support of his boyfriend and that encouraged him to continue.

18 notes

·

View notes