#edit: I ended up giving it a quick read and fixing a couple misspelled words in the end

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I already saw so many ignorant¹ takes on this movie and I am infinitely glad to see that someone took the time to provide a founded analysis touching all the main points.

Throwing my two cents in, I would like to point out also that this story heavily relies on the language of myth and of jungian psychoanalysis, and it declares it openly, too: it is not by chance that Defoe's character is a Swiss man by the name of Von Franz²!

There are many levels of interpretation to this story (which make it the more beautiful to me personally), on the queer aspect I think that it is important to note how both Ellen and Anne do not have any agency in their relationships except when it comes to the relationship with each other. It is the only non transactional relationship in the whole plot, disinterested pure love if you will; it would not be less pure (to me, at least) if the erotic aspect of it would be explicit but that exactly is one of the cornerstones of the whole narration! The purest of feelings gets distorted as well and thrown in the cauldron of every single thing Ellen represses, and the Repressed finds its form in Orlok.

Everything we repress gets thrown on the same pile, so to speak, and if one is not able to deal with it, bring it to the surface one way or the other... well, that's when the monsters appear. There are things that we must repress in order not to just be a walking danger to ourselves and others (like, you might want to strike an asinine coworker but you just do not do that. Maybe you deal with it buy punching a bag during kickboxing class, or you draw a comic in which your coworker's head explodes) and there are innocent things that society or our environment teaches us to repress for no valid reason: we kinda label them as bad and chuck them down into this pit where everything intertwines and gets distorted. It takes a lifetime of ongoing work to sort it all out, usually it is not enough. Part of the work is looking straight at the monster and accept that the monster is us, and finding ways to let it out that don't leave us sick of ourselves. The Repressed is like a pressure cooker: it explodes if the steam doesn't find a way out.

What this movie portrayed so masterfully is also that even if we need to set boundaries and analyse and understand and put everything into boxes - and that's good and necessary, part of the human condition is also accepting that a clear line, a clear boundary is not always possible to find. Between Good and Evil, or Apollonean and Dyonisian, Reason and Energy, Instinct and Rationality there is no clear demarcation line... it's a spectrum.

¹I am not sure that I am using the adjective super correctly, as English is not my native language. I find a lot of these takes ignorant because they stop at a very superficial level and refuse to acknowledge that there might be something else, something more. On top of thag when one tries to points down that there actually is more than let's say romantic novel tropes to it people just straight away refuse to acknowledge it. It shows ignorance not as a neutral state (i.e. not being aware of something) but rather as a stubborn need for confirmation bias, a refusal to be open to new things, and a callous lack of curiosity. I think it has to do with a widespread form of neopuritanism which I personally find a huge problem, and very irritating.

²Marie-Louise von Franz was a psychologist and scholar who collaborated with C.J. Jung and produced insanely valuable work (more than his in many respects, ahem) analysing myth, fairy tales and alchemical manuscripts from a psychological point of view.

Blurred Lines: Agency and Victimhood in Gothic Horror

Seeing as Robert Eggers' Nosferatu has just breached a cool $135M at the worldwide box office, it might be as good a time to talk about this as any. I believe I echo the sentiments of most diehard fans of gothic horror when I say this: while we are glad to see this masterpiece meet with well-deserved success, these numbers also mean that a significant proportion of its audience has been previously unfamiliar with the hallmarks of our beloved genre; and the resulting disconnect between the viewers and the source material has been the driving force behind the great majority of the online discourse that surrounds it.

The tools and conventions of the gothic, as a genre, are essential to Nosferatu's primary narrative arc. Its central character, Ellen Hutter, cannot be discussed outside of her literary context. Textually, she balances between heroine and damsel in distress - blurred, in many ways, from mainstream understanding.

That is done entirely on purpose. There are numerous reasons for it; I could go into heavy detail about it; and I will - under the cut, of course.

The main thing I must make absolutely clear (before delving any deeper) is that the gothic genre is fundamentally non-literal. It deals heavily in metaphor, allegory, allusion, obfuscation - and, indeed, the blurred lines that have recently caused so much controversy online. This is by design. It is not a flaw of storytelling or interpretation. The gothic affronts the rigid, black-and-white, mainstream forms of morality because that is what it has always been designed to do; and the newer installments like Nosferatu do the same, being built upon those traditional foundations.

The historical background is therefore essential to the understanding of a gothic narrative. In this, the film does provide the viewer with a relatively easy starting point; its period setting amplifies its connection to its predecessors, as well as the societal pressures and systemic violence that it aims to challenge. It allows the audience to perceive the story through a historical lens that comes pre-installed, as a sort of short-cut to the genre's original social context.

The context, in this case, consists of misogyny, queerphobia, xenophobia, and ableism - which, while rampant even in the modern day, were that much more blatant in 1830s German Confederation, where/when the story largely takes place. Every human character, regardless of who they are, is influenced by these oppressive aspects of their society; and Ellen Hutter is hopelessly entrapped within all four.

Her social situation, as we are given to understand, is precarious. Though she was originally born into wealth, she married down to escape her abusive father. She is an eccentric - her "wild" inclinations (such as having a sense of dignity or loving the outdoors as a child) are enough to cause almost vitriolic disapproval; but on top of that, she was born with a psychic gift, which manifests in a way that is not dissimilar from a mental (and sometimes physical) disability. She and her husband are also English immigrants, and thus perpetual outsiders in Wisborg (this is also one of the reasons Thomas is so anxious to prove himself at Knock's firm, and so keen to emulate Harding in all things); and, finally, she implied to experience queer attraction - which, though non-explicit, repressed, and never truly indulged, still affects her and the way she is continuously treated throughout the film.

Overall, Ellen's existence is perceived, at best, as an inconvenience - and at worst, a scandal. With that, she fits seamlessly into her story's genre.

The "immoral," the forbidden, the taboo is a cornerstone of all gothic fiction. It exists in the doubt between light and dark, harm and desire, love and abuse. It is the domain of sympathetic villains (e.g. Heathcliff, Wuthering Heights), of imperfect victims (Bertha Mason, Jane Eyre), of heroes who are deeply flawed, who cause their own tragedies, and often fail to save anyone at all (Victor Frankenstein, Frankenstein). Within the gothic genre, there are no absolutes; and its contradicting balance of dichotomies provides a reference point - or, more accurately, a cultural triangulation - for exploring the same complexities that a binary puritanical mindset strives to eradicate. These include sexual desire, female autonomy, physical and mental disabilities, classism; in short, anything that gets people wincing.

The discussion of these topics is still heavily medicalized, and rarely straightforward or productive. As stated above, it makes people uncomfortable. It's not pleasant. However, for Ellen (and many people in the real world), it is, quite literally, impossible to avoid. It defines every aspect of her daily life.

What this means for her and for the story is that within a narrative that refuses to gloss over the imperfections of her surrounding society, her victimhood is not thrust upon her by a shadowy figure, emerging from the night. Instead, she is a victim - of an ongoing and systemic, rather than individual, abuse.

This aspect of Ellen's characterization lies at the core of her behaviour throughout the film. She is an unstable chimera of Brontë's Jane Eyre and Bertha Mason - in the sense that her actions are informed, in great part, by her acute awareness of her own disenfranchisement. She alternates between anguished raving and phlegmatic practicality, used to her pain but unable to entirely ignore it; and, the same way that Jane sees all the rage she feels (but cannot afford to express) manifested in Bertha, Ellen finds her counterpart in Orlok.

This is where the ambiguity begins.

Even though Orlok is most certainly a gothic villain, his relationship with Ellen cannot be interpreted as strictly adversarial. Naturally, it would be easy to ascribe their dynamic to grooming and PTSD; however, as previously mentioned, a gothic narrative is never surface-level - and the film itself never furnishes any information that would definitively limit it to that.

Firstly, to get the primary discourse point out of the way - yes, when Ellen and Orlok first meet within the ether, she is indeed young; and later, she is said to have been a child. However, at the time, the term "teenager"did not yet exist; Ellen's younger self is not portrayed by a child actress; and later, in 1838, she is referred to as a child multiple times - despite being an adult, married woman. Overall, within the film, the term is more often used to describe innocence and inexperience, rather than age; and her initial age is never specified. Granted, a multi-century age gap is not exactly "healthy" anyway - but this is a vampire story. It is per the course; and it complicates their relationship beyond a simple victim vs abuser narrative.

Secondly - and perhaps, most importantly - the overall impact of Orlok's coercion tactics falls flat in comparison to Ellen's human-world alternatives. Yes, he argues and threatens; but her social circumstances have never allowed her agency in the first place. Her father abuses, isolates, and threatens to institutionalize her; Thomas dismisses her concerns as "childish fantasies"; Harding and Sievers tie her down and drug her; Harding again kicks her out of the house. Her marriage, her friendships, are therefore all transactional; they grant her an escape from her father's house, relative financial stability, social support - on the condition that she represses her true self, pretends to be normal, doesn't threaten anyone's masculinity or heterosexuality, and acts like she's happy to be a deferring, obedient, settled wife. Being a daughter of a landed gentleman, she would never have been given a working woman's education, and evidently has no income of her own; and so, she has no options except to upkeep her end of the bargain - which means that her continued survival within mainstream society relies on constant background coercion.

Compared to this mundane, socially acceptable horror of her existence, the vampire actually offers her more autonomy than she is ever otherwise accorded. The terms of his covenant never threaten Ellen's own well-being; so on one hand, she has benevolence - and on the other, the dignity of choice.

This contrast lies at the heart of her dilemma. Ellen is torn between what she believes she should be and what she knows - and Orlok knows - she is.

One is "correct," moral, Good; the other is "wrong," sinful, Evil. However, at the same time, the first is manufactured; it is artificially designed, and must be continuously enforced. The second is primal. Natural. In accordance with gothic tradition, the appeal of Orlok is that he is forbidden, yet instinctive. By design, he is a reflection of everything that Ellen is forced to repress on a daily basis. That includes her rage, her ostracism, her abnormalities; but also, her desperate need to be respected, understood, and desired. He is both grotesque and alluring, both a lord and a beast, both cruel and reverent.

"He is my melancholy!.." cries Ellen.

"I am Heathcliff!" whispers Cathy.

Still, while Cathy and Heathcliff are primarily divided by class and racism, Orlok and Ellen are separated by moral considerations. In the explicit sense, Ellen cannot choose the Evil that Orlok represents. Within the surface narrative, she is obligated by her society, her morals, and the story to choose Good - in this case, by nobly sacrificing her individual expendable life to save her husband and a city full of people. Her primary storyline, like everything else, has already been decided for her.

For the Trekkies among us, this is Ellen's own Kobayashi Maru. A no-win scenario. As such, within the context of character analysis, her destination does not matter as much as the little things she does along the way; and it is no accident that, as the film progresses, the subtler, seemingly insignificant choices she makes within that framework just happen to bring her closer - and closer - to Orlok.

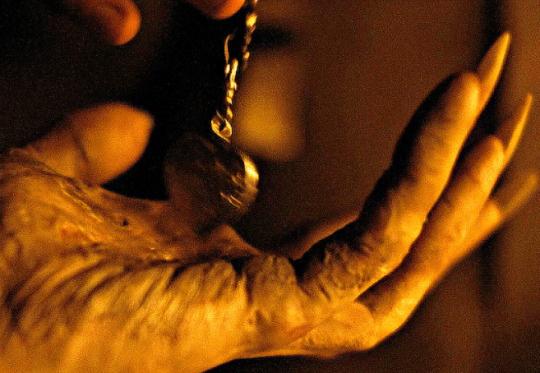

All of them are just innocuous enough to almost pass. She places a lock of perfumed hair in a locket that she gives to Thomas - and upon his arrival to the Carpathians, the same locket is immediately claimed by Orlok, who recognizes the scent of lilacs. Before making her sacrifice, she puts on her wedding dress and finds a bouquet of the same flowers - which is the sort of effort she didn't have to perform, especially given that he cannot resist her blood regardless. When Orlok arrives, she chooses to undress them both, and leads him to the bed, even though her previous sex scene with Thomas was entirely clothed; and in the morning, she pulls him close and holds him through the sunrise - even though he was already dying, and would not be able to escape. There was no need for her to touch his rotting flesh at that point, much less caress it.

There can be a "moral" explanation for all these actions; but the lack of direct obligation involved in them becomes increasingly blatant over the course of the story, and the doubt festers.

This sort of lingering ambiguity is precisely where gothic horror thrives - and intersects, scandalously, with romance. Gothic horror, much like bodice-ripper novels, noir thrillers, or "dark romance," builds much of its romantic intensity on the dichotomy of shame and desire. Imagine it, if you will, as a loom; warp and weft. It may even be described as literary BDSM - a continuous, mutually-agreed-upon act of roleplay between the author and their audience, and sometimes the characters themselves (though that depends). The point is to create an outlet for female, queer, or disabled sexualities, all of which are still heavily medicalized and restricted, derided, or denied entirely; and within these often intersecting genres, the violent or coercive intensity of the dominant lead (be it a vampire, a mafia don, or simply a more experienced lesbian) provides their repressed, seemingly passive counterpart an excuse to act upon their demonized erotic urges.

Between the page and the mind, everything that normally complicates a romantic or sexual encounter in the real world (subliminal hints, aggression, repressed and involuntary responses) becomes set dressing - serving to place a particular scene or dynamic within its fictional universe. The resulting Watsonian uncertainty is, naturally, part of the appeal. It is what allows the viewer/reader/listener a sincere emotional and sensual immersion; and for Ellen and Orlok, it provides an appropriately dramatic pretext for a night of tender vampire sex.

The discourse around their joining is painfully similar to the same that drifts around online every winter - in regards to the classic holiday hit, Baby it's Cold Outside. The song, written during an era in which extramarital sexuality was heavily restricted, follows a couple brainstorming excuses for the lady to stay the night; this intention was explicitly stated by both members of the original duet; but that hasn't stopped thousands of people from interpreting it as a "rape anthem." It is unsurprising, then, that an element of horror (guilt, shame, repression, coercion) muddles the water even further.

It's oddly apt, considering that the film premiered on Christmas Day.

Granted, I am not denying that there is an abusive aspect to Ellen and Orlok's connection, romantic or otherwise. However, to reduce Ellen to merely his "victim" is extremely inaccurate to her actual portrayal - because, within the framework of the film, her interactions with Orlok are the few in which she is actually able to exercise some form of agency. She never defers to him, their wedding-death hinges on her free will, as coerced as it may appear; and, in a fascinating subversion of a popular vampire trope, she is the one who summons him.

In gothic media, "Come to me!.." is invariably spoken by a vampire (or a vampire derivative like Erik, Leroux's titular Phantom of the Opera); their counterpart follows helplessly, without question; and giving these lines to Ellen is a dramatic deviation from tradition that fundamentally alters the underlying context of their power balance. By maintaining this call-and-response dynamic throughout the story, Eggers asserts that Ellen isn't helpless; and neither is she "in over her head." She is intelligent, powerful, and she has a tangible influence over Orlok, who is her only equal - which is why, ultimately, she is the one deciding where that relationship is headed.

That is not to say that any alternative readings of the film are entirely incorrect. As I have stated above, the abusive/toxic narrative is definitely present, and even essential, in gothic media. On the Doylist level, it is the equivalent of a whip, or a solid pair of cuffs - essentially, a divestment of responsibility; though, to continue the metaphor, not everyone shares the same kink - and those who do might not all enjoy it the same way, so there's definitely significant variation. What I am trying to say, however, is that each story does come with a central conflict; and Ellen Hutter's victimization - much like Jane Eyre's, like Thomasin's (The Witch, 2015) - is systemic.

She is ostracized, disrespected - infantilized if her oppressors are feeling benevolent, demonized when they are inconvenienced - and still expected to always prioritize her husband/friends/community by default, regardless of how she is treated by them. Her surrounding society, morality, religion, culture all insist upon the same; and this is why, despite knowing that she has done nothing wrong by following her nature, she carries an enormous amount of guilt in regards to those "unacceptable" aspects of herself. It is also the same reason why Orlok - the sensual, cruel, utterly devoted monster - is the answer to her lonely call; and the reason why everyone around her is so eager to see her as his victim, rather than a victim of anything they may have perpetrated themselves. Ellen's is a rich complexity, fed upon centuries' worth of gothic tradition, and she cannot be forced into a flat, genre-inappropriate simplification.

Like The Witch, like NBC Hannibal, like Interview With the Vampire before it - Nosferatu (2024) is a story of self-indulgence being so unfamiliar that it feels like a sin; or, like dying.

I, for one, would not deny her that.

#nosferatu#gothic literature#myth#psychoanalysis#archetypes#I'm writing on mobile and the app is fucking around#also don't get fooled by the footnotes I didn't proofread any of this so don't come at me fornmy grammar thx#edit: I ended up giving it a quick read and fixing a couple misspelled words in the end

82 notes

·

View notes