#eastern block unity etc

Text

I forbid myself from starting any new wip before I finish homingbird but

I do have ideas for FAM fics… specifically an AU from 2x07 onwards wherein we change the timeline so the Russians don’t shoot down the KAL plane, no one shoots on the Moon and NASA and South Koreans get invited to Moscow to work on a new joint mission…

#I’m reading master and margarete again and let me tell you#the Moscow I imagine based on family tales from when my family visited in the 80s#eastern block unity etc#I have a visceral reaction to most things Russian these days but weirdly I think it gives me the right headspace for this au#the need to get Sergei out of there and let the Soviet Union crash and burn will be very clear#adventures in fic writing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monarchy of the Father Part 1 - The Language

In an earlier article, I bemoan the fact that too many evangelicals have never heard of the Monarchy of the Father (MOF). This is a bizarre state of affairs given the fact that MOF is virtually ubiquitous among the pro-Nicenes of the 4th century.

What I didn’t do in that article, however, is explain what MOF is actually supposed to be. In the next two articles, I’ll sketch out MOF as I currently understand it.

Part 1 will explore MOF as a way of talking about the Trinity. By this I simply mean that I will introduce the language deployed by many of the pro-Nicenes to speak of Father, Son, Holy Spirit, and God.

Part 2 will explore MOF as a way of understanding the Trinity. My intent will be to unpack the logic of MOF--a logic that secures for us an orthodox Trinitarian model of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

In both articles, my primary influences are the works of Athanasius, the Cappadocians, John Behr, Beau Branson, Christopher Beeley, and Richard Cross. All have been crucial partners in my search for an orthodox model of the Trinity that makes sense of Scripture and the 4th century.

I’ve also had some very helpful interactions with Skylar McManus, John Sobert Sylvest, David Mahfood, Robert Dryer, and a number of others on Theology Twitter.

These articles are meant to be a primer or introduction to MOF. I hope they might be particularly helpful for those struggling with a Trinitarianism that, among other things, seems disconnected from Scripture.

The Scriptural Disconnect

It’s no secret that conventional language used to speak about the Trinity is quite different from the language found in Scripture.

God is triune: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The church believes, adores, and worships the one simple divine essence, which exists three times over, as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, inseparably united in life and in action, one in everything save in their relations of origin.[1]

...the Trinity is God. God is God in this way: God’s way of being God is to be Father, Son, and Holy Spirit simultaneously from all eternity, perfectly complete in a triune fellowship of love.[2]

The central dogma of Christian theology [is] that the one God exists in three Persons and one substance, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. God is one, yet self-differentiated; the God who reveals Himself to mankind is one God equally in three distinct modes of existence, yet remains one through all eternity.[3]

All of these ways of speaking are meant to affirm that the “one God” is the Trinity. Or put another way, the “one God” is a tri-personal God--one God in three persons.

Now, it’s certainly the case that there are those who understand this tri-personal God language quite well. Generally, this would be a person who is well read on the doctrine of the Trinity and its development.

Such a person typically swims in the waters of two highly respected Latins, Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. He or she speaks the language of “three distinct modes of existence.” He or she can parse out this tri-personal God language and its affirmations within assorted Biblical, historical, logical, theological, and philosophical models.

Scripture, on the other hand, does not “speak of the one God as self-differentiated into three.”[4] It does not make these assorted tri-personal God articulations--”God is the Trinity,” or “He is the Trinity,” or “three persons and one essence.” It does not *call* the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit together the “one God.”[5]

The problem, and this is from personal experience, is that this language can be a stumbling block for the uninitiated--even more so when they are trying to make sense of this language with a Bible in their laps or listening to the average sermon.

Aware of this problem, it is common practice to attempt to simplify this language and teach something like, God is “three who’s and one what.”

Does this help? Considering the number of personal pronouns that show up, I’m not so sure. Let me demonstrate--He, God the Trinity, is three He’s (three persons) and a “what.” That’s four he’s and a what!

A legitimate question, when teaching or catechizing the uninitiated or confused, is whether this language is the best place to start. The answer repeatedly seems to be, “Yes.” Why?

There exists a deeply embedded assumption that this tri-personal “one God in three persons” language is the only player in town (the Latin waters have a strong current). This assumption has even pervaded the way many read the Trinitarian MOF language of the 4th century.[6]

Given this assumption, it appears there are no other options for speaking about the Holy Trinity. This language is all we have and the best we have.

Yet, if we read outside of our Latin-influenced tradition and engage with Greek-influenced traditions (such as the Eastern Cappadocian Fathers), we encounter an utterly different kind of Trinitarian language--the Monarchy of the Father.

MOF Trinitarianism Language

MOF Trinitarian language has at least three ground floor affirmations:

The “one God” is the Father.

The Father, the “one God,” is the cause, source, and principle of the Son and the Holy Spirit, and thus the Trinity itself (thus the term, “Monarchy”).

The Son and the Holy Spirit are homoousios or consubstantial with the “one God” the Father. In other words, the Son and Spirit exemplify the “one God’s” divinity.

With respect to point one, notice that in MOF language the “one God” is not the Trinity. The “one God” is not a referent to the tri-personal God who exists in three persons. The “one God” is the Father.

In fact, identifying the Father as the “one God” is crucial to the logic of MOF Trinitarian language. We will see that in Part 2.

With respect to points two and three, the Father is seen as the cause, source, and principle of the Son and Spirit (and thus the Trinity) because of how each relate to him. In other words, to properly grasp who they are, we must know how they relate to the “one God.”

These points are specifically highlighted in the Trinitarian MOF language of the Cappadocian, Gregory of Nazianzus.

...when he gives a summary statement of his own doctrinal position he chooses to emphasize not the triune equality, as we might expect (though this is indicated), still less the unity or consubstantiality of the three persons...Gregory conspicuously anchors the identity of each figure—and the divine life altogether—in the unique role of God the Father as source and cause of the Trinity. Although it may seem striking to modern interpreters, he defines the faith in the biblical and traditional pattern of referring to God primarily as ‘‘the Father,’’ just as the creed of Nicaea had done.[7]

This language and its three basic affirmations is a language that is “firmly rooted...in the Bible.”[8] It takes its cues directly from the Scripture.

The New Testament, for example, speaks exclusively of the Father as the “one God.”

1 Corinthians 8:6a (NET) — 6a yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we live...

Ephesians 4:6 (NET) — 6 one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.

1 Timothy 2:5a (NET) — 5 For there is one God and one intermediary between God and humanity, Christ Jesus... [Christ is the intermediary between the “one God,” who is the Father, and humanity]

The Bible also repeatedly speaks in terms of how the Son of God and the Holy Spirit relate to God (the Father).

Hebrews 1:3a (ESV) — 3a He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature

Colossians 1:15(ESV) — 15 He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.

Philippians 2:5–6 (ESV) — 5 Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, 6 who, though he was in the form of God [the Father], did not count equality with God [the Father] a thing to be grasped,

John 5:26 (ESV) — 26 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself.

John 17:3 (ESV) — 3 And this is eternal life, that they know you, the only true God [the Father], and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.

John 14:16 (ESV) — 16 And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Helper, to be with you forever,

John 15:26 (ESV) — 26 But when the Helper comes, whom I will send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father, he will bear witness about me.

Also taking its cues from Scripture, the Nicene-Constantinople Creed of 381 codifies this Biblical Trinitarian MOF language. Below is a sampling of this ecumenical Creed.

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father;

And in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of life, who proceedeth from the Father, who with the Father and the Son together is worshiped and glorified, who spake by the prophets.

Notice here, like with Scripture, that the Father is the “one God.” Notice, too, that the Son and Spirit are spoken of in terms of their relation to this “one God.”

It is also striking that the word “Trinity” and the tri-personal “God in three persons” language is not present. This is significant because it is this Creed that is affirmed by all of orthodox Christianity as the baseline for Trinitarianism.

Conclusion

So my goal has been to provide a primer or introduction to Trinitarian MOF language as I understand it. I hope I’ve succeeded. My intent is not to persuade. I just want to provide some options to those who might desperately need them.

This language, no doubt, raises some questions. What does it mean that the Son and Spirit are “caused?” Is Jesus God? Is he subordinate to the Father? Is the Holy Spirit God? Does MOF language work with the normative “one God in three persons” language? Etc.

For now, I’ll leave you with John Behr describing the Trinitarian MOF language of another Cappadocian Father, Gregory of Nyssa:

Gregory does not identify “God” as that which is common, a genus to which various particular beings belong; nor does he speak of the one God as three. Rather, “the God overall” is known specifically as “Father,” and the characteristic marks of the Son and the Spirit relate directly to him...[9]

Stay tuned for Part 2.

[1] Stephen R. Holmes. The Quest for the Trinity: The Doctrine of God in Scripture, History and Modernity (Kindle Locations 1462-1463). Kindle Edition.

[2] Sanders, Fred. The Deep Things of God: How the Trinity Changes Everything (p. 62). Crossway. Kindle Edition.

[3] F.L. Cross, ed., 3rd ed. rev. E.A. Livingstone, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 1641.

[4] Behr, John. The Nicene Faith (p. 5). Crestwood, NY, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

[5] It doesn't preclude such language either.

[6] In The Quest for the Trinity, Stephen Holmes summarizes 4th century Trinitarianism in seven points. HIs third point assumes that the tri-personal God affirmation is a basic feature of 4th century Trinitarianism: “There are three divine hypostases that are instantiations of the [one] divine nature: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

[7] Beeley, Christopher. Gregory of Nazianzus on the Trinity and the Knowledge of God (p. 204). Oxford University Press.

[8] Ibid. p. 209.

[9] Behr, John. One God Father Almighty (p. 328). Modern Theology 34:3, July 2018.

#the trinity#monarchy of the father#cappadocians#nicene-constantinople creed#john behr#christopher beeley#one god#pro-nicene#nicene faith

0 notes

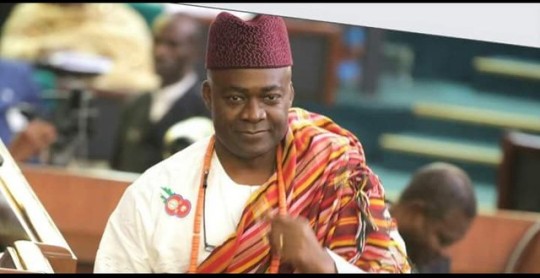

Photo

Democracy Day Message HON. SERGIUS OGUN REELS OUT ACHIEVEMENTS, TASKS CONSTITUENTS ON PEACE, UNITY MAY 30, 2018 BLOG By Kingsley Ohens 0 Comments Democracy Day Message HON. SERGIUS OGUN REELS OUT ACHIEVEMENTS, TASKS CONSTITUENTS ON PEACE, UNITY Full text of the message as released by his media team yesterday: Nearly three years ago, I was privileged to take the oath of office as your elected representative in the lower chamber of the National Assembly of our dear country, the third to serve you in that capacity since the return to democratic rule in 1999. Today, I remember that day and the processes leading to it with profound gratitude to God Almighty and to all who worked very hard to ensure the success of our tedious journey from Agbazilo to Abuja. As we celebrate Democracy Day which interestingly shares a contiguous proximity with the third anniversary of my inauguration as a member of the the 8th session of the National Assembly, it is proper for us to take stock of our gains in the past 36 months. In the light of this, please permit me to run through the list of our modest achievements so far. On AGRICULTURE, I initiated the establishment of the Agbazilo Mechanized Constituency Farm Oria. The farm which sits on a vast expanse of fertile land has an administrative block, farm warehouse, borehole, two tractors, ploughs, harrows and other powered tools. The farm is fully mechanized in every sense of the word – from clearing, planting to harvesting . Two hundred young men and women benefitted from the first farming circle, with one hectare allotted to each beneficiary. After harvest, proceeds from the sales of the crops go to the beneficiaries. The farming scheme, no doubt, would help to reduce the rate of youth employment while reigniting the flames of agricultural revival. Away from the mechanized farm, I facilitated the refurbishment of the Federal Department of Agriculture Ubiaja in order to revive and reposition the agricultural establishment for better performance. On EDUCATION, I rehabilitated a block of six classrooms at Ugboha Secondary Commercial School and constructed a block of two classrooms at Otoikhimhin Primary School Ugboha . Work is in progress at Uzogbon Primary School Ugboha where a block of three classrooms is being constructed. I completed a block of six classrooms at Iruele Primary School Uromi and a block of three classrooms at Ukpekimiokolo Primary School Uromi- both projects were initiated by my predecessor Rt. Hon. Barr. Friday Itulah. Between 2015 and 2018, I Enrolled NECO/SSCE for 2,400 final year students( 600 students per year) and granted automatic university scholarship to the overall best six Sergius Oseasochie Ogun Foundation NECO/SSCE Mock Exam candidates each year, as stated above. I sponsored the distribution of free notebooks to all public/private nursery, primary and secondary schools in the federal constituency with each pupil/student receiving five notebooks in 2015, 2016 and 2017 respectively. At the tertiary level, I presented #100,000 and #50,000 cash prizes to the best graduating Esan HND and ND students in Auchi Polytechnic in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Moved by the desire to ameliorate the rising wave of unemployment and mass migration of young men and women to Libya, I granted scholarship to 187 young school leavers to undergo a three-month intensive technical training programme at the National Institute of Construction Technology Uromi so that they can acquire relevant skills and become self reliant. On ROAD, I facilitated the construction of Ugboha-Anegbete Road, Oria Road ( one kilometre) and rehabilitation of Uromi Angle 90 – Ubiaja Road. I also Facilitated resumption of work on Adaokere-Ukoni Road(ongoing) and the reconstruction of failed sections of Uromi-Agbor Road, even as I mount pressure on the federal government to expedite action on the dualization of Ewu- Uromi – Agbor Road. On SKILL ACQUISITION &ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT, I donated 5 tricycles, 20 motorcycles, 50 sewing machines and 20 grinding machines to constituents to curb the festering effects of the economic recession which held the nation to a criminal ransom in 2016. I sponsored the training of 200 farmers on the production of cassava bread, cassava cake, cassava chips, fruit juice and other recipes. My constituency office in collaboration with the National Directorate of Employment organized skill acquisition training programme for 100 young women on cosmetic production. In addition to the foregoing, I sponsored the first ever music talent hunt in the federal constituency and rewarded the winners with mouth-watering cash prizes. On HEALTH, I initiated and sponsored free medical outreaches at Uzea, Emu, Ewohimi, Ubiaja, Oria, Ohordua,Ewatto, Ugboha and Amendokhian, Utako, IIdumoza and Efandion-Uromi in 2015, 2016 and 2017 and 2018. I facilitated the provision of medical equipment worth millions of naira for Uzogbon Primary Health Care Centre Ugboha, Olinlin Primary Health care Centre Uzea and Illushi Primary Health care Centre. I facilitated the installation of solar lights at the premises of Uromi General Hospital. On WATER, I did my little best to ensure the completion of the Northern Esan Water Project. I Constructed a borehole each at Uzea and Emunekhua in response to the demand of the people of the two communities for hygienic water. On ELECTRICITY, I facilitated the upgrading of BEDC substation at Oyomon, Uromi, and the restoration of power supply to some communities that were disconnected by BEDC On EMPLOYMENT, I secured employment for some graduates in public/ private establishments and recommended many for possible consideration. On MOTIONS and BILLS, I have sponsored the following motions and bills on the floor of the House of Representatives from 2015 till date. 1. Urgent Need to Rehabilitate the Roads Linking the Otor Bridge and Connecting Delta/South Eastern States and the Northern Parts Of Nigeria 2. Urgent need to investigate the activities of the Nigerian oil industry regulatory authorities and the need to complete all ongoing and outstanding unitization processes of straddled oil and gas fields and for other matters connected therewith 3. Need to provide welfare and rehabilitation centres for the critically – ill and physically challenged 4. Need for a comprehensive audit of all sources of revenue in Nigeria 5. Urgent need to complete and commission the Northern Esan water supply scheme 6. The need to investigate reported massive fraud in Nigeria’s N117 billion rice import quota scheme 7. The need to investigate allegations of financial scandal and gross abuse of office by Pension Transitional Arrangement Directorate (PTAD) management 8. Need to compel the Nigeria Civil Aviation Authority and other relevant regulatory authorities in the Aviation Sector to conduct routine checks on the state of Aircrafts operating within Nigeria and make public the reports 9. A resolution for the immediate establishment of an emergency response and ambulance bay by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), at Ewu Hills, along the Benin-Abuja Federal Highway, Ewu,Edo State 10. Urgent need to mandate the Federal Airports Authority of Nigeria to beef up and strengthen security apparatus and checks at our Nation’s Airports 11. Need to revive farm storage facilities to boost Agricultural production and distribution in Nigeria 12. Need to regulate the indiscriminate levy of Agricultural produce, livestock, etc on our Federal Roads 13. Need to stem the serious flooding at Illushi and Ifeku Island communities in Esan South East Local Government Area of Edo State 14. Need to mandate the national agency for food and drug administration and control to check the ensure that food and drinks prepared and served in hotels, fast food restaurants and any other restaurants meet globally accepted hygiene standards 15. Urgent need to impress upon the executive arm of government the importance of obeying court orders. 16. Calling on the Federal Roads Maintenance Agency (FERMA) and the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) to as a matter of urgency do rehabilation works on the Irrua-Uromi-Illushi road, Uromi-Agbor road and the Ewohimi-OnichaUgbo road 17. Urgent need for Federal Government intervention to tackle gully erosion challenges in Emu Town, Esan South East Local Government Area of Edo State 18. Need to encourage the establishment of crèche facilities in Government offices and buildings 19. Need to investigate the procurement process employed in Nigeria’s High commissions and Embassies with a view to cutting cost and fighting corruption. 20. Urgent Need to Investigate the resurgence of Avian Influenza popularly known as Bird Flu. 21. Need to investigate the scarcity and incessant hike in the price of Liquefied Petroleum Gas (popularly referred to as cooking Gas) in Nigeria 22. Need to investigate the recurrent occurrence of Lassa fever in Nigeria. 23. Urgent need to investigate the positioning of advert billboards on pedestrian bridges and their effect on the security of pedestrians 24. Need to consider the construction industry for priority forex allocation *stepped down 25. Need to investigate the relatively high cost of malaria tests and drugs in government hospitals 26. Need to regulate the use of Bisphenol A (BPA) plastics in production of bottled water 27. Need to evaluate the effect of withdrawal of HIV funding by international donors 28. Need for the review of Nigerian Public Financial Management System and Supreme Audit Institution 29. Urgent call for the removal of surcharge on mutilated notes by the Central Bank of Nigeria 30. Call for a cost analysis of the monies recovered by the EFCC and the cost of prosecution of cases 31. A call to control the manufacturing and use of single-use plastic bags (polythene) and replace with biodegradable or fabric material 32. Need to increase tobacco tax to curb public health danger and fund healthcare services 33. Need for the implementation of the National Broadband plan 34. Urgent need to stop the killings/attacks of herdsmen on Ugboha community in Esan North East/ Esan South East Federal Constituency, Edo State 35. Continued implementation of the Federal Capital Territory Statutory Appropriation Act, 2017 and for other related matters, pursuant to sections 122 and 299 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, as amended 36. Free Advice and Treatment of Breast Cancer Centre Bill, 2016 37. National Centre for Agricultural Mechanization Act (Amendment Bill) 2016 38. Nigerian Institute of Agriculturists (Establishment) Bill 2016 39. Labour Act (Amendment Bill) 2016 40. Public Officers Protection Act (Amendment Bill) 2016 41. Nigerian Law Reform Commission Act (Amendment Bill) 2017 42. International studies (Regulation Bill) 2017 43. Public Officers International Medical Trip 44. Federal Capital Territory Emergency Management Agency 45. National Orientation Agency Act (amendment) bill, 2017 46. National Health Act (amendment) bill, 2017 47. Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Outdoor Signage and Advertisement Agency Bill, 2017 48. National Institute of Construction Technology and Management (Establishment) Bill, 2018 Time will fail me to enumerate, in detail, all the good things we have done, and are doing to make things better for our dear constituency, and our great nation. Suffice it to say that the task of making our constituency a better place is the responsibility of us all. To this end, I urge that, you all cultivate in your heart, a commitment to do more to support my efforts in every way possible. As we zoom into the final lap of our four-year term, let us therefore resolve to place the higher interests of peace, unity and development above all other considerations. Together we can achieve more! Long live Esan North East/South East Federal Constituency! Long live Edo State! Long live Federal Republic of Nigeria! Signed. Hon., Barr., Dcn Sergius Oseasoshie Ogun Member, House of Representatives Esan North East/South East Federal Constituency Edo State.

0 notes

Text

baloch national identity in karachi

Download

Heterogeneity and the Baloch Identity

20AUG

Professor Dr. Taj Mohammad Breseeg

By Professor Dr. Taj Mohammad Breseeg

University of Balochistan, Quetta

Introduction

As the saying goes, “nations are built when diversity is accepted, just as communities are built when individuals can be themselves and yet work for and with each other.” In order to understand the pluralistic structure of the Baloch society, this paper begins with a critical study of the Baloch’s sense of identity, by discarding idealist views of national identity that overemphasize similarities. From this perspective, identity refers to the sharing of essential elements that define the character and orientation of people and affirm their common needs, interests, and goals with reference to joint action. At the same time it recognizes the importance of differences. Simply put, a nuanced view of national identity does not exclude heterogeneity and plurality. This is not an idealized view, but one rooted in sociological inquiry, in which heterogeneity and shared identity together help form potential building blocks of a positive future for the Baloch.

Yet the dilemma of reconciling plurality and unity constitutes an integral part of the definition of the Baloch identity. In fact, one flaw in the thinking by the Baloch about themselves is the tendency toward an idealized concept of identity as something that is already completely formed, rather than as something to be achieved. Hence, there is a lack of thinking about the conditions that contribute to the making and unmaking of the Baloch national identity. The belief that unity is inevitable, a foregone conclusion, flows from this idealized view of it.

Another equally serious flaw is the tendency among some of the Baloch nationalists to think in terms of separate and independent forces of unity and forces of divisiveness, ignoring the dialectical relationship between these forces. Thus, we have been told repeatedly that there are certain elements of unity (such as language, common culture, geography, or shared history) as well as certain elements of fragmentation (such as communalism, tribalism, localism, or regionalism). If, instead, we view these forces from the vantage point of dialectical relations, the definition of Baloch identity involves a simultaneous and systematic examination of both the processes of unification and fragmentation. This very point makes it possible to argue that the Baloch can belong together without being the same; similarly, it can be seen that they may have antagonistic relations without being different.

The Sense of Belonging

The specificity of Balochistan geography and geopolitics has affected and shaped the character of the Baloch, their vision of the world and the way they have continued to reproduce and reinterpret their cultural elements and traditions. The Baloch myths and memories persist over generations and centuries, forming contents and contexts for collective self-definition and affirmation of collective identities in the face of the other.[1]

Located on the south-eastern Iranian plateau, with an approximately 600,000 sq. km., an area rich with diversity, that also incorporates within it a wide social variety, Balochistan is larger than France (551,500 sq. km.).[2] It is an austere land of steppe and desert intersected by numerous mountain chains. Naturally, the climate of such a vast territory has extraordinary varieties.[3] In the northern and interior highlands, the temperature often drops to 400 F in winter, while the summers are temperate. The coastal region is extremely hot, with temperature soaring between 1000 to 1300 F in summers, while winters provide a more favourable climate. In spite of its position on the direction of southwest monsoon winds from Indian Ocean, Balochistan seldom receives more than 5 to 12 inches of rainfall per year due to the low altitude of Makkoran’s coastal ranges.[4] The ecological factors have, however, been responsible for the fragmentation of agricultural centres and pasturelands, thus shaping the formation of the traditional tribal economy and its corresponding socio-political institutions.[5]

Balochistan’s geographical location between India and the Mesopotamian civilization had given it a unique position as cross roads between earlier civilizations. Some of the earliest human civilizations emerged in Balochistan, Mehrgar the earliest civilization known to man kind yet, is located in eastern Balochistan, the Kech civilization in central Makkuran date back to 4000 BC, Burned city near Zahidan, the provincial capital in western Balochistan date back to 3000 BC. Thus, by the course of time, a cluster of different religions, languages and cultures coexisted side by side. Similarly in the Islamic era we see the flourishing of different sects of Islam (Sunni, Zikri and Shia), remarkable marriage of tribal and semi-tribal society enriched with colourful cultural and traditional heritage.[6]

The Baloch, probably numbering close to 15 million, are one of the largest trans-state nations in southwest Asia.[7] The question of Baloch origins, i.e., who the Baloch are and where they come from, has for too long remained an enigma. Doubtless in a few words one can respond, for example, that Baloch are the end-product of numerous layers of cultural and genetic material superimposed over thousands of years of internal migrations, immigrations, cultural innovations and importations.Balochistan, the cradle of ancient civilizations, has seen many races, people, religions and cultures during the past few thousand years. From the beginning of classical history three old-world civilizations, Dravidian, Semitic and Aryan, met, formed bonds, and were mutually influenced on the soil of Balochistan. To a lesser or greater extent, they left their marks on this soil, particularly in the religious beliefs and the ethnic composition of the country.[8]

The exact meaning and origin of the term Baloch is somewhat cloudy. Its designation may have a geographical origin, as is the case of many nations in the world. Etymological view supported by some scholars is that the name Baloch probably derives from Gedrozia or “Kedrozia” the name of the Baloch country in the time of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC)”.[9] The term Gedrozia with the suffix of “ia” seems to be a Greek or Latin construction, like Pers-ia , Ind -ia, Kurdia, etc. Gedrozia, the land of the rising sun, was the eastern most Satrapy (province) of the Median Empire. Probably, its location was the main source of its designation as “Gedroz or Gedrozia”. It should be noted that there are two other eastern countries in the Iranian plateau, namely Khoran and Nimroz, both have their designation originated from the same source, the sun. They are known as the lands of rising sun. Like the suffix “istan”, Roz (Roch) is also a suffix for various place and family names construction in Iranian languages.

Having studied the etymology of the term “Kurd”, the Kurdish scholar Mohammad Amin Seraji believes that the term “Baloch” is the corrupted form of the term Baroch or Baroz. Arguing on the origin and the meaning of the term, Seraji says, the Baroz has a common meaning both in Kurdish and Balochi, which means the land of the rising sun (ba-roch or “toward sun”). Locating at the eastern most corner of the Median Empire, the county probably got the designation “Baroch or baroz” during the Median or early Achaemenid era, believes Seraji. According to him, there are several tribes living in Eastern Kurdistan, who are called Barozi (because of their eastward location in the region). Based on an ancient Mesopotamian text, some scholars, however, opine that the word “Baloch” is a corrupted form of Melukhkha, Meluccha or Mleccha, which was the designation of the modern eastern Makkoran during the third and the second millennia B.C.[10]

Historically, defeating the Median Empire in 549 BC, the mightiest Persian King, Darius (522-485), subjugated Balochistan at around 540 B.C. He declared the Baloch country as one of his walayat(province) and appointed a satrap (governor) to it.[11] Probably it was during this era, the Madian and the later Persian domination era, the Baloch tribes were gradually Aryanised, and their language and the national characteristics formed. If that is the case, the formation of the Baloch ethno-linguistic identity should be traced back to the early centuries of the first millennium BC.

Etymologically speaking, there are many territorial or regional names, which are derived after the four cardinal points (East, West, North and South).[12] For example, the English word Japan is not the name used for their country by the Japanese while speaking the Japanese language: it is an exonym.[13]The Japanese names for Japan are Nippon and Nihon. Both Nippon and Nihon literally mean “the sun’s origin”, that is, where the sun originates, and are often translated as the Land of the Rising Sun. This nomenclature comes from Imperial correspondence with Chinese Sui Dynasty and refers to Japan’s eastward position relative to China.

Being a Balochi endonym, the origin of the word “Balochistan” can be identified with more precision and certainty. The term constitutes of two parts, “Baloch” and “–stan”. The last part of the name “-stan” is an Indo-Iranian suffix for “place”, prominent in many languages of the region. The name Balochistan quite simply means “the land of the Baloch”, which bears in itself a significant national connotation identifying the country with the Baloch.[14] Gankovsky, a Soviet scholar on the subject, has attributed the appearance of the name to the “formation of Baloch feudal nationality” and the spread of the Baloch over the territory bearing their name to this day during the period between the 12th and the 15th century.[15]

The Baloch may be divided into two major groups. The largest and the most extensive of these are the Baloch who speak Balochi or any of its related dialects. This group represents the Baloch “par excellence”. The second group consists of the various non-Balochi speaking groups, among them are the Baloch of Sindh and Punjab and the Brahuis of eastern Balochistan who speak Sindhi, Seraiki and Brahui respectively. Despite the fact that the latter group differs linguistically, they believe themselves to be Baloch, and this belief is not contested by their Balochi-speaking neighbours. Moreover, many prominent Baloch leaders have come from this second group.[16] Thus, language has never been a hurdle for Balochs’ religious and cultural unity. Even before the improvement of roads, communication, printing, “Doda-o Balach and Shaymorid-o Hani” stories were popular throughout the length and breadth of Balochistan.

Despite the heterogeneous composition of the Baloch, however, in some cases attested in traditions preserved by the tribes, they believe themselves to have a common ancestry. Some scholars have claimed a Semitic ancestry for the Baloch, a claim which is also supported by the Baloch genealogy and traditions, and has found wide acceptance among the Baloch writers. Even though this belief may not necessarily agree with the facts (which, it should be pointed out, are very difficult to prove, either way), it is the concept universally held among members of the group that matters. In this connection Kurdish nationalism offers a good parallel. The fact is that there are many common ethnic factors which have contributed to the formation of the Kurdish nation; there are also factors which have led to divisions within the Kurds themselves. While the languages identified as Kurdish are not the same as the Persian, Arabic, or Turkish, they are mutually unintelligible. Geographically, the division between the Kurmanji-speaking areas and the Sorani-speaking areas correspond with the division between the Sunni and Shiite schools of Islam. Despite all these factors, the Kurds form one of the oldest nations in the Middle East.Tribal loyalties continue to dominate the Baloch society, and the allegiance of the majority of the Baloch have been to their extended families, clans, and tribes. The Baloch tribes share an ideology of common descent and segmentary alliance and opposition. These principles do actually operate at the level of the smaller sub-tribes, but they are contradicted by the political alliances and authority relations integrating these sub-tribes into larger wholes. In a traditional, tribal society a political ideology such as Baloch nationalism would be unable to gain support, because loyalties of tribal members do not extend to entities rather than individual tribes. The failure of the tribes to unite in the cause of Baloch nationalism is a replay of tribal behaviour in both the Pakistani and Iranian Baloch revolts. Within the tribes, an individual’s identity is based on his belonging to a larger group. This larger group is not the nation but the tribe. However, the importance of the rise of a non-tribal movement over more tribal structures should not be underestimated. In this respect the Baloch movements of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s provide us a good example.[17]

The Baloch have devised a nationalist ideology, but realise that the tribal support remains a crucial ingredient to any potential success of a national movement. By accepting the support of the tribes, however, the nationalists fall vulnerable to tribal rivalries. Tribal ties, however, are of little significance in southern Balochistan (both Pakistani and Iranian Balochistan), Makkoran, which was originally a stratified society, with a class of nominally Baloch landowners controlling the agricultural resources. The great majority of the tribes in Balochistan view them and are viewed by outsiders as the Baloch.[18]

Politically, the British occupation of the Baloch State of Kalat in 1839 was perhaps the greatest event and turning point in the Baloch history. From the very day the British forces occupied Kalat state, Baloch destiny changed dramatically. The painful consequences for the Baloch were the partition of their land and perpetual occupation by foreign forces. Concerned with con taining the spread of the Russian Socialist Revolution of 1917, the British assisted Persian to incorporate western Balochistan in 1928 in order to strengthen the latter country as a barrier to Russian ex pansion southward. The same concern also led later to the annexation of Eastern Balochistan to Pakistan in 1948.

Thus, colonial interests worked against the Baloch and deprived them of their self-determination and statehood. Confirming this notion, in 2006, in a pamphlet, the Foreign Policy Centre, a leading European think tank, launched under the patronage of the British Prime Minister Tony Blair, revealed that it was British advice that led to the forcible accession of Kalat to Pakistan in 1948. Referring reliable British government archives, the Foreign Policy Centre argues, that the Secretary of State Lord Listowell advised Mountbatten in September 1947 that because of the location of Kalat, it would be too dangerous and risky to allow it to be independent. The British High Commissioner in Pakistan was accordingly asked “to do what he can to guide the Pakistan government away from making any agreement with Kalat which would involve recognition of the state as a separate international entity”.[19]

Since the early 20th century, Balochistan’s political boundaries do not conform to its physical frontier; they vary widely. Eastern Balochistan with Quetta as its capital has been administered by Pakistan since 1948; western Balochistan, officially known as “Sistan-wa-Balochistan” with Zahedan as its capital, has been under the control of Iran since 1928; and the Northern Balochistan known as the Walayat-i-Nimrooz, has been under the Afghan control since the early 20th century.

Shared History

As the Kurd, Baloch make a large ethnic community in the Southwest Asia without a state of their own. Baloch folk tales and legends points out that major shift of Baloch population to the present land of Balochistan were brought about in different times and different places. From linguistic evidence, it appears that the Baloch migrated southward from the region of the Caspian Sea. Viewed against this background, the Baloch changed several geographical, political and social environments. Thus from the very beginning they learned to adjust themselves with different cultures and way of life.

The Baloch history is a chain of unsuccessful uprisings for autonomy and independence. It tells about genocide, forcible assimilation, deportation and life in exile. Since its inception, the Baloch national identity has been seen as based primarily on such experiences. However, the early political history of the Baloch is obscure. It appears to have begun with the process of the decline of the central rule of the Caliphate in the region and the subsequent rise of the Baloch in Makkoran in the early years of the 11th century.[20] The Umawid general Mohammad bin Qasim captured Makkoran in 707 AD. Thereafter, Arab governors ruled the country at least until the late 10th century when the central rule of the Abbasid Caliphate began to decline.[21]

The period of direct Arab rule over Makkoran lasted about three centuries. By gradually accepting Islam, the scattered Baloch tribes over vast area (from Indus in the east, to Kerman in the west), acquired a new common identity, the Islamic. Thus Islam gave them added cohesion.[22] The Arab rule also relieved them from the constant political and military pressure from Persia in the north. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, they benefited materially from the growth of trade and commerce which flourished in the towns and ports under the Arabs, reviving the old sea and land-based trade routes that linked India to Persia and Arabia through western Makkoran.[23]

Under the Arab rule, the Baloch tribal chiefs became a part of the privileged Muslim classes, and identified themselves with the Arab caliphate and represented it in the region. The conflicts between the Arab caliphate and the Baloch on the one hand, and the neighbouring non-Muslim powers on the other, strengthened the “Muslim” identity of the Baloch, while the conflicts between the Arab caliphate and the Baloch contributed to their “tribal unity and common” consciousness. The threats posed to the Arab Empire and to the Baloch, would gradually narrow the gap between the warlike Baloch tribes. In this process, Islam would function as a unifying political ideology and promote a common culture among the Baloch tribal society and its different social classes as a whole. These developments appear to have played a significant role in enabling the Baloch to form large-scale tribal federations that led to their gradual political and military supremacy in the territories now forming Balochistan during the period of 11th to 13th centuries.[24] Thus, the early middle ages saw the first emergence of a distinctive Baloch culture and the establishment of the Baloch principalities and dynasties. As the power of Arabs after the first Islamic staunch victory declined with fragmentation of Islam across the Sunni and Shiites theological lines, the Baloch tribes moved to fill the administrative, political and spiritual vacuum.

Since the 12th century the Baloch formed powerful tribal unions. The confederacy of forty-four tribes under Mir Jalal Khan in the 12th century, the Rind-Lashari confederacy of the fifteenth century, the Maliks, the Dodais, the Boleidais, and the Gichkis of Makkoran, and the Khanate of Balochistan in the 17thcentury, united and merged all the Baloch tribes at different times. Moreover, the invasions of the Mughals and the Tatars, the wars and the mass migrations of the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries, and the cross tribal alliances and marriages, contributed to the shaping of the Baloch identity.[25]

Thus, historical experiences have played an important role to the formation of the Baloch national identity. In this regards the Swiss experience shows a remarkable similarity. In the Swiss case strength of common historical experience and a common consensus of aspirations have been sufficient to weld into nationhood groups without a common linguistic or cultural background. The history of the Baloch people over the past hundred years has been a history of evolution, from traditional society to a more modern one. (“More modern” is a comparative term, and does not imply a “modern” society, i.e. a culminating end-point to the evolution.) As such, the reliance on tribal criteria is stronger in the earlier movements, and the reliance on nationalism stronger in the later ones. Similarly, the organizing elements in the early movements are the tribes; the political parties gradually replace the tribes as mass mobilization is channeled into political institutions.[26]

Culture and the Baloch Identity

Geography helps, because it accustoms the Baloch to the idea of difference. Thus, the Baloch culture owes much to the geography of the country. The harsh climate and mountainous terrain breeds a self-reliant people used to hardship; the same conditions, however, result in isolation and difficulties in communication. In terms of physical geography, Balochistan has more in common with Iranian plateau than with the Indian subcontinent. On the north, it is separated from India by the massive barrier of the southern buttresses of the Sulaiman Mountains. On the south, there is the long extension from Kalat of the inconceivably wild highland country, which faces the desert of Sindh, the foot of which forms the Indian frontier. The cultural heartland lies in the interior, in the valleys of Kech, Panjgur and Bampur in the Southern and central Balochistan.[27]

Being expressed through language, literature, religion, customs, traditions and beliefs, culture is a complex of many strands of varying importance and vitality. The Balochs’ adjustability, accommodation and spirit of tolerance enable their culture survive several vicissitudes. The Baloch people are distinct from the Punjabi and the Persian elite that dominate Pakistani and Iranian politics – they are Muslims but more secular in their outlook (in a similar fashion to the Kurds) with their own distinct language and culture. Spooner points to the importance of the Balochi language as a unifying factor between the numerous groups nowadays identifying themselves as “Baloch”. He wrote, “Baluch identity in Baluchistan has been closely tied to the use of the Baluchi language in inter-tribal relations”.[28] In spite of almost half a century of brutal assimilation policy, both in Iran and Pakistan, the Baloch people have managed to retain their culture and their oral tradition of story telling. This explains the tendency to dismiss the existing states as artificial and to call for political unity coinciding with linguistic identity. The prevailing view is that only a minority of the people of Balochistan lack a sense of being Baloch; this minority category includes the Persians of Sistan and the Pashtuns of Eastern Balochistan.[29]

It is, however, worth mentioning that the linguistic and ethnic plurality had been the rule in the almost all Baloch tribal unions in the past. The Rind-Lashari union of the 15 century, the Zikri state of Makkuran and the Brahui Confederacy of Kalat, all constituted of diverse tribal confederacies. No attempt had been made to force Kalat subjects to speak Brahui, a large number of tribes did not speak it as their first language and perhaps most Kalat subjects did not speak it at all. The Brahui tribes spoke Barahui, the Lasis and Jadgal spoke Jadgali, and the Baloch spoke Balochi.

Being a tribal people, religion plays a less important role in the daily life of the Baloch. It is generally believed that before the emergence of the Islamic fundamentalism in the region, Baloch were not religiously devout as compared to their neighbours, the Persians, Punjabis and the Pashtuns. Their primary loyalties were to their tribal leaders. Unlike the Afghan he is seldom a religious bigot and, as Sir Denzil Ibbetson, in mid-19th century described the Baloch, “he has less of God in his head, and less of the devil in his nature”[30] Thus, historically speaking, the Baloch always have had a more secular and pluralistic seen on religion than their neighbours.

Because the Pakistani state assumed the mantle of two-nation theory (Islam/Hinduism) based on Islam for its legitimacy, as a countermovement one can expect most Baloch to rely on ethno-nationalism. In 1947, Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo voiced the Baluch opinion against the religious nationalism of Pakistan: “We are Muslims but it (this fact) did not mean (it is) necessary to lose our independence and to merge with other (nations) because of the Muslim (faith). If our accession into Pakistan is necessary, being Muslim, then Muslim states of Afghanistan and Iran should also merge with Pakistan.”[31]

As mentioned earlier, linguistically the Baloch society is diverse. There are a substantial number of Brahui speakers in the central and northern Balochistan who are culturally very similar to the Baloch, and the Baloch, who inhabit the Indus Plains, Punjab and Sindh retain their ethnic identity though they now speak Sindhi or Seraiki. Although Brahui and Balochi are unrelated languages, multi-lingualism is common among them. Having considered this reality, Tariq Rahman believes, “The Balochi and Brahvi languages are symbols of the Baloch identity, which is a necessary part of Baloch nationalism.”[32]

Of the various elements that go into the making of the Baloch national identity, probably the most important is a common social and economic structure. For while many racial strains have contributed to the making of the Baloch people, and while there are varying degrees of differences in language and dialect among the various groups, a particular type of social and economic organisation, comprising what has been described as a “tribal culture”, is common to them all. This particular tribal culture is the product of environment, geographical, and historical forces, which have combined to shape the general configuration of Baloch life and institutions. Describing the Baloch economy in early 1980s, a prominent authority on the subject of Baloch nationalism, Selig S. Harrison wrote, “Instead of relying solely on either nomadic pastoralism or on settled agriculture, most Baloch practice a mixture of the two in order to survive”.[33]

A classic sociological principle proposes a positive relationship between external conflicts and internal cohesion.[34] One such exclusive focus is the constantly expressed view that the only thing the Baloch agree on is the hatred of Gajar (Persian) and Punjabi dominance. The common struggle against the alien invaders, while strengthening the common bonds, develops national feelings. According to Peter Kloos, for reasons that are still very unclear, people confronted with powerful forces that lie beyond their horizon, and certainly beyond their control, tend to turn to purportedly primordial categories, turning to the familiarity of their own ethnic background. In the process they try to gain an identity of their own by going back to the fundamentals of their religion, to a language unspoken for generations, to the comfort of a homeland that may have been theirs in the past. In doing so, they construct a new identity.[35]

The Baloch people face unique challenges contingent on the nation-state in which they reside. For example, in Iran, where the Baloch are thought to comprise more than two million are restricted from speaking Balochi freely and have been subjected in military operations by the Persian dominated state. The harsh oppression of the Iranian and Pakistani states has strengthened the Balochs’ will to pass on their heritage to coming generations. The Balochi language is both proof and symbol of the separate identity of the Baloch, and impressive efforts are made to preserve and develop it.[36] Having realized the significance of the language (Balochi) as the most determinant factor for the Baloch identity, the Persian and Punjabi dominated states of Iran and Pakistan have sought to “assimilate” the Baloch by all possible means.[37]

Globalization and the Baloch Identity

Since the early 2000, electronic media has been a continually changing forum for communicating, which has been taken up by the Baloch communities to maintain connections with their brethren all over the world. In that capacity, the technology has been an easy and innovative avenue for cultural expression. The Baloch, for instance, have established on-line magazines, newsgroups, human rights organizations, student groups, academic organizations and book publishers for a trans-national community. Some of these informative and insightful English media include: Balochistan TV,radiobalochi.org, balochvoice.com, balochunity.org, balochinews.com, zrombesh.org, baloch2000.orgetc. Based out of the country, they have significantly contributed to the development of the Baloch identity.

The revival of ethnic identity is converging with the emergence of continental political and economic units theoretically able to accommodate smaller national units within overarching political, economic, and security frameworks. The nationalist resurgence is inexorably moving global politics away from the present state system to a new political order more closely resembling the world’s ethnic and historical geography. Thus, the new world order may hold light of hope for oppressed ethnic communities, who have survived empires, colonization, nation building processes by brutal neighbors who systematically eroded them, reduced their existence to rival tribes. Therefore, contrary to the globalist argument, the new media are not eroding the sense of national identity but rather reinforcing and providing it with a broader and much independent context to an ethno cultural identity across the juridical boundaries of states to strengthen and solidify its distinct cultural identity.

Conclusion

There is a general consensus among the scholars about the Baloch community with regard to heterogeneity in Baloch political society, that voluntary association, independence, autonomy, equality and consultation had remained its basic principles and ingredients. It is the idea of an ever-ever land – emerging from an ancient civilization, united by a shared history, sustained by pluralistic way of life. In fact this way of life made it possible for people with different social realities come under the umbrella of a free, willingly accepted social and cultural code. The Baloch em braced and assimilated other minor groups to extend their strength. The pre sent-day Baloch are not a single race, but are a people of different origins, whose lan guage belong to the Iranian family of languages. They are mixed with Arabs in the South, Indians in the East, and with Turkmen and other Altaic groups in the North West.

The very survival of the Baloch, as a distinctive nation is characterised by decentralisation and diversity: diversity of racial origins, of dialects, of tribes and communities, of religions. But it’s diversity within a unity, provided by common tribal culture, common history, common experiences and common dreams. Thus, it is necessary to understand the forces of unity and the forces of divisiveness in relation to each other. These forces operate within the context of underlying conflicts and confrontations and under certain specific conditions. The Baloch identity is therefore developed to the extent that it manifests itself through a sense of belonging and a diversity of affiliations. The Baloch also recognize a shared place in history and common experiences. Similarly, social formations and shared economic interests have helped to shape the Baloch identity. And, finally, the baloch identity is shaped by specific, shared external challenges and conflicts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baloch, Inayatullah, The Problem of Greater Baluchistan: A Study of Baluch Nationalism, Stuttgart : Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GMBH, 1987.

Baluch, Muhammad Sardar, History of Baluch Race and Baluchistan, Quetta : Khair – un -Nisa, Nisa Traders, Third Edition 1984;

Baluch, Muhammad Sardar, The Great Baluch: The Life and Times of Ameer Chakar Rind 1454- 1551 A .D., Quetta , 1965.

Breseeg,Taj Mohammad, Baloch Nationalism: Its Origin and Development, Karachi, Royal Book Company, 2004.

Harrison, Selig S., In Afghanistan’s Shadow: Baluch Nationalism and Soviet Temptations, New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1981.

Holdich, Thomas, The Gate of India : Being a Historical Narrative, London , 1910. Sabir Badalkhan, “A Brief Note of Balochistan”, unpublished, 1998. This ariticle was submitted to the Garland Encyclopedia of World Folklore, New York-London, (in 13 vols): vol. 5, South Asia, edited by Margaret Mills.

Hosseinbor, M. H., “Iran and Its Nationalities: The Case of Baluch Nationalism”, PhD. Thesis, The Amerikan university, 1984.

Jahani, Carina, “Poetry and Politics: Nationalism and Language Standardization in the Balochi Literary Movement” in: Paul Titus (ed.), Marginality and Modernity: Ethnicity and Change in Post-Colonial Balochistan, Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Kloos, Peter, “Secessionism in Europe in the Second Half of the 20th Century” in: Nadeem Ahmad Tahir (ed.), The Politics of Ethnicity and Nationalism in Europe and South Asia, Karachi , 1998.

Malik Allah-Bakhsh, Baluch Qaum Ke Tarikh ke Chand Parishan Dafter Auraq, Quetta :, Islamiyah Press, 20 September, 1957.

Possehl, Gergory L., Kulli: An Exploration of Ancient Civilization in Asia, Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 1986.

Rahman,Tariq, “The Balochi/Brahvi Language Movements in Pakistan ”, in: Journal of South Asian and Middle East Studies Vol. XIX, No.3, Spring 1996.

Spooner, Brian, “Baluchistan: Geography, History, and Ethnography” (pp. 598-632), In: Ehsan Yarshater, (ed), Encyclopadia Iranica, Vol. III, London – New York : Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1989.

The Foreign Policy Centre, Balochis of Pakistan : On the Margins of History, Foreign Policy Centre, London 2006.

The Gazetteer of Baluchistan: Makran, Quetta: Gosha-e Adab (repr. 1986).

The Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. VI, Oxford : Calaredon Press, 1908.

INTERVIEWS:

Seraji, Mohammad Amin, leading political figure since 1950’s, from Iranian Kurdistan, was borne in September 1934, Mahabad Kurdistan, educated from the faculty of Law, University of Tehran . Interview made in Stockholm in April 2006, (on tape in Persian).

[1] Muhammad Sardar Khan Baluch, History of Baluch Race and Baluchistan, Quetta : Khair – un -Nisa, Nisa Traders, Third Edition 1984, p. 26.

[2] Inayatullah Baloch, The Problem of Greater Baluchistan, 1987, pp. 19-23; See also Janmahmad, Essays on Baloch National Struggle in Pakistan, p. 427.

[3] For a good description of the natural climate of Western Balochistan see Naser Askari, Moghadamahi Bar Shenakht-e Sistan wa Balochistan, Tehran: Donya-e Danesh, 1357/1979 pp. 3-14.

[4] Ibid., p. 9

[5] Taj Mohammad Breseeg, Baloch Nationalism: Its Origin and Development, Karachi, Royal Book Company, published in 2004, p. 64.

[6] Ibid., pp. 74-77.

[7] For more information, see Ibid., pp. 66-70.

[8] Gergory L. Possehl, Kulli: An Exploration of Ancient Civilization in Asia , pp. 58-61.

[9] Taj Mohammad Breseeg, Baloch Nationalism: Its Origin and Development, Karachi, Royal Book Company, published in 2004, p. 56.

[10] J. Hansman, “A Periplus of Magan and Melukha”, in BSOAS, London , 1973, p. 555; H. W. Balley, “Mleccha, Baloc, and Gadrosia”, in: BSOAS, No. 36, London , 1973, pp. 584-87. Also see, Cf. K. Karttunen, India in Early Greek Literature, Studia Orientalia, no. 65, Helsinki : Finnish Oriental Society, 1989, pp. 13-14.

[11] I. Afshar (Sistani), Balochistan wa Tamaddon-e Dirineh-e An, pp. 89-90.

[12] Etymology is the study of the history of words — when they entered a language, from what source, and how their form and meaning have changed over time. In languages with a long detailed history, etymology makes use of philology, the stu how words change from culture to culture over time. However, etymologists also apply the methods of comparative linguistics to reconstruct information about languages that are too old for any direct information (such as writing) to be known. By analyzing related languages with a technique known as the comparative method, linguists can make inferences, about their shared parent language and its vocabulary. In this way, word roots have been found which can be traced all the way back to the origin of, for instance, the Indo-European language family.

[13] An exonym is a name for a place that is not used within that place by the local inhabitants (neither in the official language of the state nor in local languages, or a name for a people or language that is not used by the people or language to which it refers. The name used by the people or locals themselves is called endonym . For example, Deutschland is an endonym; Germany is an English exonym for the same place.

[14] That is also the case with other similar names such as Kurdistan (the Kurdish homeland), Arabistan (the Arab homeland), Uzbakistan, etc. In these names, the Persian affix “istan” meaning land or territory is added to the name of its ethnic inhabitants.

[15] Yu. V. Gankovsky, The People of Pakistan : An ethnic history, pp. 147-8.

[16] Many prominent Baloch nationalists, such as Mir Gaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, Sardar Atuallah Megal, Gul Khan Nasir are Brahui-speaking.

[17] Breseeg, 2004, pp. 195-227.

[18] Ibid., pp. 92-95.

[19] The Foreign Policy Centre, Balochis of Pakistan : On the Margins of History, Foreign Policy Centre, London 2006.

[20] M. H. Hosseinbor, “ Iran and Its Nationalities: The Case of Baluch Nationalism”, pp. 45-46.

[21] Ibid., and see Breseeg, p. 109.

[22] The Imperial Gazetteer of India , vol. VI, Oxford : Calaredon Press, 1908, p. 275.

[23] Thomas Holdich, The Gate of India : Being an Historical Narrative, London , 1910, pp. 297-301. See also Dr. Sabir Badalkhan, “A Brief Note of Balochistan”, unpublished, 1998. This ariticle was submitted to the Garland Encyclopedia of World Folklore, New York-London, (in 13 vols): vol. 5, South Asia , edited by Margaret Mills.

[24] Ibid.

[25] For more detail, see Inayatullah Baloch, The Problem of Greater Baluchistan, pp. 89-125.

[26] Breseeg, 2004, pp. 248-51.

[27] It was in Makkuran that the early middle ages saw the first emergence of a distinctive Baloch culture and the establishment of the Baloch principalities and dynasties.

[28] Brian Spooner, Baluchistan: Geography, History, and Ethography p. 599.

[29] Breseeg, 2004, pp. 361-63, 296-98.

[30] Sir Denzil Ibbeston, The races, castes and tribes of the people in the report on the Census of Punjab , published in 1883, cited in: Muhammad Sardar Khan Baluch, The Great Baluch, pp. 83-100. It is important to note that the Baloch way of life influenced the way in which Islam was adopted. Up to tenth century as observed by the Arab historian Al-Muqaddasi the Baloch were Muslim only by name (Al-Muqaddasi, Ahsanul Thaqasim, quoted in Dost Muhammad Dost, The Languages and Races of Afghanistan, Kabul, 1975, p. 363.) Similarly, Marco Polo, at the end of the thirteenth century, remarls that some of people are idolators but the most part are Saracens (The Gazetteer of Baluchistan: Makran, p. 113).

[31] Malik Allah-Bakhsh, Baluch Qaum Ke Tarikh ke Chand Parishan Dafter Auraq, Quetta :, Islamiyah Press, 20 September, 1957 , p. 43.

[32] Tariq Rahman, “The Balochi/Brahvi Language Movements in Pakistan ”, in: Journal of South Asian and Middle East Studies Vol. XIX, No.3, Spring 1996, p. 88.

[33] Selig S. Harrison, In Afghanistan’s Shadow, p. 8.

[34] See Peter Kloos, “Secessionism in Europe in the Second Half of the 20th Century” in: Tahir, Nadeem Ahmad (ed.), The Politics of Ethnicity and Nationalism in Europe and South Asia, Karachi , 1998.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Carina Jahani, “Poetry and Politics: Nationalism and Language Standardization in the Balochi Literary Movement”, p. 110.

[37] Selig S. Harrison, In Afghanistan’s Shadow, pp. 95-96.

The post baloch national identity in karachi appeared first on Urdu Khabrain.

from Urdu Khabrain http://ift.tt/2C6KA56

via Daily Khabrain

0 notes

Text

baloch national identity in karachi

Download

Heterogeneity and the Baloch Identity

20AUG

Professor Dr. Taj Mohammad Breseeg

By Professor Dr. Taj Mohammad Breseeg

University of Balochistan, Quetta

Introduction

As the saying goes, “nations are built when diversity is accepted, just as communities are built when individuals can be themselves and yet work for and with each other.” In order to understand the pluralistic structure of the Baloch society, this paper begins with a critical study of the Baloch’s sense of identity, by discarding idealist views of national identity that overemphasize similarities. From this perspective, identity refers to the sharing of essential elements that define the character and orientation of people and affirm their common needs, interests, and goals with reference to joint action. At the same time it recognizes the importance of differences. Simply put, a nuanced view of national identity does not exclude heterogeneity and plurality. This is not an idealized view, but one rooted in sociological inquiry, in which heterogeneity and shared identity together help form potential building blocks of a positive future for the Baloch.

Yet the dilemma of reconciling plurality and unity constitutes an integral part of the definition of the Baloch identity. In fact, one flaw in the thinking by the Baloch about themselves is the tendency toward an idealized concept of identity as something that is already completely formed, rather than as something to be achieved. Hence, there is a lack of thinking about the conditions that contribute to the making and unmaking of the Baloch national identity. The belief that unity is inevitable, a foregone conclusion, flows from this idealized view of it.

Another equally serious flaw is the tendency among some of the Baloch nationalists to think in terms of separate and independent forces of unity and forces of divisiveness, ignoring the dialectical relationship between these forces. Thus, we have been told repeatedly that there are certain elements of unity (such as language, common culture, geography, or shared history) as well as certain elements of fragmentation (such as communalism, tribalism, localism, or regionalism). If, instead, we view these forces from the vantage point of dialectical relations, the definition of Baloch identity involves a simultaneous and systematic examination of both the processes of unification and fragmentation. This very point makes it possible to argue that the Baloch can belong together without being the same; similarly, it can be seen that they may have antagonistic relations without being different.

The Sense of Belonging

The specificity of Balochistan geography and geopolitics has affected and shaped the character of the Baloch, their vision of the world and the way they have continued to reproduce and reinterpret their cultural elements and traditions. The Baloch myths and memories persist over generations and centuries, forming contents and contexts for collective self-definition and affirmation of collective identities in the face of the other.[1]

Located on the south-eastern Iranian plateau, with an approximately 600,000 sq. km., an area rich with diversity, that also incorporates within it a wide social variety, Balochistan is larger than France (551,500 sq. km.).[2] It is an austere land of steppe and desert intersected by numerous mountain chains. Naturally, the climate of such a vast territory has extraordinary varieties.[3] In the northern and interior highlands, the temperature often drops to 400 F in winter, while the summers are temperate. The coastal region is extremely hot, with temperature soaring between 1000 to 1300 F in summers, while winters provide a more favourable climate. In spite of its position on the direction of southwest monsoon winds from Indian Ocean, Balochistan seldom receives more than 5 to 12 inches of rainfall per year due to the low altitude of Makkoran’s coastal ranges.[4] The ecological factors have, however, been responsible for the fragmentation of agricultural centres and pasturelands, thus shaping the formation of the traditional tribal economy and its corresponding socio-political institutions.[5]

Balochistan’s geographical location between India and the Mesopotamian civilization had given it a unique position as cross roads between earlier civilizations. Some of the earliest human civilizations emerged in Balochistan, Mehrgar the earliest civilization known to man kind yet, is located in eastern Balochistan, the Kech civilization in central Makkuran date back to 4000 BC, Burned city near Zahidan, the provincial capital in western Balochistan date back to 3000 BC. Thus, by the course of time, a cluster of different religions, languages and cultures coexisted side by side. Similarly in the Islamic era we see the flourishing of different sects of Islam (Sunni, Zikri and Shia), remarkable marriage of tribal and semi-tribal society enriched with colourful cultural and traditional heritage.[6]

The Baloch, probably numbering close to 15 million, are one of the largest trans-state nations in southwest Asia.[7] The question of Baloch origins, i.e., who the Baloch are and where they come from, has for too long remained an enigma. Doubtless in a few words one can respond, for example, that Baloch are the end-product of numerous layers of cultural and genetic material superimposed over thousands of years of internal migrations, immigrations, cultural innovations and importations.Balochistan, the cradle of ancient civilizations, has seen many races, people, religions and cultures during the past few thousand years. From the beginning of classical history three old-world civilizations, Dravidian, Semitic and Aryan, met, formed bonds, and were mutually influenced on the soil of Balochistan. To a lesser or greater extent, they left their marks on this soil, particularly in the religious beliefs and the ethnic composition of the country.[8]

The exact meaning and origin of the term Baloch is somewhat cloudy. Its designation may have a geographical origin, as is the case of many nations in the world. Etymological view supported by some scholars is that the name Baloch probably derives from Gedrozia or “Kedrozia” the name of the Baloch country in the time of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC)”.[9] The term Gedrozia with the suffix of “ia” seems to be a Greek or Latin construction, like Pers-ia , Ind -ia, Kurdia, etc. Gedrozia, the land of the rising sun, was the eastern most Satrapy (province) of the Median Empire. Probably, its location was the main source of its designation as “Gedroz or Gedrozia”. It should be noted that there are two other eastern countries in the Iranian plateau, namely Khoran and Nimroz, both have their designation originated from the same source, the sun. They are known as the lands of rising sun. Like the suffix “istan”, Roz (Roch) is also a suffix for various place and family names construction in Iranian languages.

Having studied the etymology of the term “Kurd”, the Kurdish scholar Mohammad Amin Seraji believes that the term “Baloch” is the corrupted form of the term Baroch or Baroz. Arguing on the origin and the meaning of the term, Seraji says, the Baroz has a common meaning both in Kurdish and Balochi, which means the land of the rising sun (ba-roch or “toward sun”). Locating at the eastern most corner of the Median Empire, the county probably got the designation “Baroch or baroz” during the Median or early Achaemenid era, believes Seraji. According to him, there are several tribes living in Eastern Kurdistan, who are called Barozi (because of their eastward location in the region). Based on an ancient Mesopotamian text, some scholars, however, opine that the word “Baloch” is a corrupted form of Melukhkha, Meluccha or Mleccha, which was the designation of the modern eastern Makkoran during the third and the second millennia B.C.[10]

Historically, defeating the Median Empire in 549 BC, the mightiest Persian King, Darius (522-485), subjugated Balochistan at around 540 B.C. He declared the Baloch country as one of his walayat(province) and appointed a satrap (governor) to it.[11] Probably it was during this era, the Madian and the later Persian domination era, the Baloch tribes were gradually Aryanised, and their language and the national characteristics formed. If that is the case, the formation of the Baloch ethno-linguistic identity should be traced back to the early centuries of the first millennium BC.

Etymologically speaking, there are many territorial or regional names, which are derived after the four cardinal points (East, West, North and South).[12] For example, the English word Japan is not the name used for their country by the Japanese while speaking the Japanese language: it is an exonym.[13]The Japanese names for Japan are Nippon and Nihon. Both Nippon and Nihon literally mean “the sun’s origin”, that is, where the sun originates, and are often translated as the Land of the Rising Sun. This nomenclature comes from Imperial correspondence with Chinese Sui Dynasty and refers to Japan’s eastward position relative to China.

Being a Balochi endonym, the origin of the word “Balochistan” can be identified with more precision and certainty. The term constitutes of two parts, “Baloch” and “–stan”. The last part of the name “-stan” is an Indo-Iranian suffix for “place”, prominent in many languages of the region. The name Balochistan quite simply means “the land of the Baloch”, which bears in itself a significant national connotation identifying the country with the Baloch.[14] Gankovsky, a Soviet scholar on the subject, has attributed the appearance of the name to the “formation of Baloch feudal nationality” and the spread of the Baloch over the territory bearing their name to this day during the period between the 12th and the 15th century.[15]

The Baloch may be divided into two major groups. The largest and the most extensive of these are the Baloch who speak Balochi or any of its related dialects. This group represents the Baloch “par excellence”. The second group consists of the various non-Balochi speaking groups, among them are the Baloch of Sindh and Punjab and the Brahuis of eastern Balochistan who speak Sindhi, Seraiki and Brahui respectively. Despite the fact that the latter group differs linguistically, they believe themselves to be Baloch, and this belief is not contested by their Balochi-speaking neighbours. Moreover, many prominent Baloch leaders have come from this second group.[16] Thus, language has never been a hurdle for Balochs’ religious and cultural unity. Even before the improvement of roads, communication, printing, “Doda-o Balach and Shaymorid-o Hani” stories were popular throughout the length and breadth of Balochistan.

Despite the heterogeneous composition of the Baloch, however, in some cases attested in traditions preserved by the tribes, they believe themselves to have a common ancestry. Some scholars have claimed a Semitic ancestry for the Baloch, a claim which is also supported by the Baloch genealogy and traditions, and has found wide acceptance among the Baloch writers. Even though this belief may not necessarily agree with the facts (which, it should be pointed out, are very difficult to prove, either way), it is the concept universally held among members of the group that matters. In this connection Kurdish nationalism offers a good parallel. The fact is that there are many common ethnic factors which have contributed to the formation of the Kurdish nation; there are also factors which have led to divisions within the Kurds themselves. While the languages identified as Kurdish are not the same as the Persian, Arabic, or Turkish, they are mutually unintelligible. Geographically, the division between the Kurmanji-speaking areas and the Sorani-speaking areas correspond with the division between the Sunni and Shiite schools of Islam. Despite all these factors, the Kurds form one of the oldest nations in the Middle East.Tribal loyalties continue to dominate the Baloch society, and the allegiance of the majority of the Baloch have been to their extended families, clans, and tribes. The Baloch tribes share an ideology of common descent and segmentary alliance and opposition. These principles do actually operate at the level of the smaller sub-tribes, but they are contradicted by the political alliances and authority relations integrating these sub-tribes into larger wholes. In a traditional, tribal society a political ideology such as Baloch nationalism would be unable to gain support, because loyalties of tribal members do not extend to entities rather than individual tribes. The failure of the tribes to unite in the cause of Baloch nationalism is a replay of tribal behaviour in both the Pakistani and Iranian Baloch revolts. Within the tribes, an individual’s identity is based on his belonging to a larger group. This larger group is not the nation but the tribe. However, the importance of the rise of a non-tribal movement over more tribal structures should not be underestimated. In this respect the Baloch movements of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s provide us a good example.[17]