#easily the most interesting thing about king james i of england/vi of scotland is who his mother was

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i just find it really interesting that both mary, queen of scots and her grandson king charles i of england and scotland both had their heads chopped off

#beheadedness skips a generation#text post#morbid thoughts that stick w me late at night#easily the most interesting thing about king james i of england/vi of scotland is who his mother was#and that her successor had her killed#second most interesting thing about james is who his father was and how he was killed. maybe by his mother?#or maybe not. it's a conspiracy either way#third most interesting thing is that he was maybe gay but honestly who really cares#of all the ambiguously maybe-queer ppl of the early-modern era i dont actually find james all that interesting; he just happened to be king

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical References in What Are You Going to Do With Your Life - Chapters 10-12

Chapter 10

Boleyn mumbles something about a priest. W. S. Pakenham-Walsh (1868 - 1960), Vicar of Sulgrave, Northhamptonshire, had a strong interest in Anne Boleyn. He claimed to have a series of spiritual experiences after praying at Boleyn’s burial site, and contacted clairvoyants to channel her spirit in the hopes she might become his guardian angel. He also claimed in his diary that he had contact with Henry VIII and other notable members of the Tudor court.

While witchcraft was often punished via the death penalty, Henry VIII made the law explicit in 1542 (though it was later repealed no later than 1547, under Edward VI). Several witchcraft laws were made in the UK over the years, in 1563, 1604, 1649 and 1735. These were all repealed and replaced with more general consumer protection laws, and the last person to be indicted for witchcraft (under the 1735 act) was imprisoned in 1944.

Tarot was a regular set of cards for most of its history, used in various, but similar, trick-taking card card games. It became associated with ancient wisdom in 1781, when Antoine Court de Gébelin wrote an essay claiming (with no evidence) that ancient Egyptian priests had distilled the mystical Book of Thoth into the cards.

“Psychic is Greek, and clairvoyant is French. One is about thinking, and the other is about seeing.” Psychic comes from the Greek word psychikos (‘of the mind’) and clairvoyance is a combination of two French words (‘clear’ and ‘vision’). Catherine of Aragon was known to speak both French and Greek, as well as Latin, her native Spanish, and English.

Cunning man (or woman) was another word for folk healers.

In 1532, Catherine Parr’s brother-in-law from her second marriage, William Neville, was accused of treason for allegedly predicting the king’s death and his own ascension as Earl of Warwick (a title made extinct during the Wars of the Roses, but would be recreated in 1547 and twice after that). He went to at least three magicians to confirm this prediction, all of which agreed that it was meant to be true (it wasn’t). One of these magicians was Richard Jones of Oxford, who was imprisoned and questioned on the matter. He did his best to exonerate himself of responsibility. I have found five references confirming his existence – but many of them claim he had a sceptre he used to ‘summon the four king devils’, which he used for divination purposes.

Chapter 11

Jones of Oxford was taken in for questioning as part of the Neville affair, and he did his best in his confession to exonerate himself. Neville’s claims of a prophetic dream showing himself as Earl of Warwick were now a “fair castle” which Neville assumed must be the castle of Warwick, and a shield with “sundry arms I could not rehearse”. He did admit to writing “a foolish letter or two according to [Neville’s] foolish desire, to make pastime to laugh at”. No treason, just jokes, please don’t execute me Thomas Cromwell. Jones claimed to take his alchemy seriously, however, and wrote that “To make the philosopher’s stone I will jeopard my life, so to do it,” if the king so wished. He would require twelve months “upon silver” and twelve and a half “upon gold”, and was willing to be imprisoned while he worked. Jones made a similar offer to Cromwell, but there is no evidence either man accepted. Jones was released in exchange for revealing incriminating evidence against another figure of interest. The other magicians caught up in this incident, William Wade and a man known only as ‘Nashe’, had perfected their disappearing act and were not sent to the Tower.

There is a story that Elizabeth I attributed the destruction of the Spanish armada in 1588 to John Dee’s wizardry. Given that, as mentioned, Dee was out of favour with Elizabeth at the time, this is likely untrue.

Elizabeth I’s death was in March of 1603, after she became sick and remained in a “settled and unmovable melancholy”, sitting on a cushion and staring at nothing. The death of a close friend in February of that year came as a particular blow – that of her second cousin and First Lady of the Bedchamber, Catherine Howard.

James I (or James VI, depending on where you’re from)… James I of England was also James VI of Scotland. His mother was Mary Queen of Scots, who was executed by Elizabeth I, and his great-grandmother was Margaret Tudor, Henry VIII’s sister.

“Anna, born Duchess of Jülich, Cleves and Berg.” This was how Anna signed hers’ and Henry’s marriage treaty, known as the ‘Beer Pot Documents’, because someone drew a stein at the bottom.

Bowling, as a game, can trace its origins back to ancient Egypt, and has been quite popular the world over throughout history. Henry VIII was an avid bowler himself (when Hampton Court was remodelled, bowling alleys were included with tennis courts and tiltyards), but banned the sport for the lower classes. The law against workers bowling (unless it was Christmas and in their master’s presence) was repealed in 1845.

We return to the ground, because from it we were taken. Paraphrasing of Genesis 3:19.

The (possible) first appearance of the word ‘alligator’ in the English language is from Romeo and Juliet. The description of The Apothecary’s shop mentions “a tortoise hung, an alligator stuff’d, and other skins of ill-shaped fishes”. Traditionally, medieval apothecaries and astrologers kept skeletons, fossils, and/or taxidermied pieces on display to demonstrate their worldliness.

The anger over calling the alligator ‘William’ could come from Parr, or from Anna. Her brother’s name, Wilhelm, is often anglicised as William.

Midsomer county does not exist and never has. It’s the setting for the long-running mystery TV show Midsomer Murders. Incidentally, Catherine Parr’s native county of Westmorland existed at one point, but no longer does (the area is now in the county of Cumbria). She is not the only English-born queen who this applies to; Jane Seymour’s Wiltshire and Anne Boleyn’s Norfolk still exist (and have since antiquity), but Katherine Howard was most likely born in Lambeth, which would have been in the county of Middlesex at the time. The area is now under the ceremonial county of Greater London.

“Honestly? Margaret Pole’s was worse.” Margaret Pole, Countess of Sailsbury and the last of the House of York, was kept in the Tower of London for two and a half years for her supposed support of Catholicism’s attempts to overthrow the king, before being informed of her death ‘within the hour’ on the 27th of May, 1541. She answered that she did not know the crime of which she was accused (and had carved a poem into the wall of her cell to that effect), but went to the block anyway. It allegedly took eleven blows from the inexperienced axeman to separate her head from her body. There is another story that she tried to run from the executioner and was killed in the attempt, but this is likely a fabrication. Regardless, pretty much everyone thought this was not only a bad idea on Henry’s part (killing Margaret removed any leverage the king had on her rebellious son, Cardinal Reginald Pole), it was also pointlessly cruel and a painfully undignified end.

(She was also Catherine of Aragon’s lady-in-waiting, and governess to Mary at several points.)

That everyone around her, bar a few visitors, would actively benefit from her death… Yet another quote of Elizabeth Tyrwhitt’s testimony: Parr, on her deathbed, claimed she was “not well-handled” by those around her; “for those that be about me careth not for me, but standeth laughing at my grief, and the more good I will to them, the less good they will to me”.

Chapter 12

According to a lady-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn claimed she would rather see Catherine of Aragon hanged “than have to confess that she was her queen and mistress”. This incident is probably the origin of the lyric “somebody hang you!” from Don’t Lose Ur Head.

Catalina uses a few Spanish phrases in this chapter, which don’t get directly translated. The first, No se hizo la miel para la boca del asno, directly translates to ‘Honey is not made for the donkey’s mouth’, and essentially means ‘Good things shouldn’t be wasted on those who won’t appreciate them’. Lavar cerdos con jabón es perder tiempo y jabón is ‘Washing pigs with soap is a waste of time and soap’, and is meant to indicate some things aren’t worth the energy.

…like that dream she has where she is cut up by a servant… An autopsy was done on Catherine of Aragon as part of the embalming process, which revealed the growth on her heart. This was done by the castle chandler (a dealer or trader) as part of his official duties.

Jane Seymour got rid of most of the hallmarks of Anne Boleyn’s tenure during her own queenship. The extravagance and lavish entertainments were banned, along with the French fashions Boleyn had introduced – including French hoods, which Boleyn is wearing in the portrait we have of her. Jane, as mentioned, wore a gable hood in her portraits.

“I don’t know why I’m so surprised that people care about what I say.” In the words of nineteenth century proto-feminist Agnes Strickland, Jane “passed eighteen months of regal life without uttering a sentence significant enough to warrant preservation”, which is kind of a mean thing to say. Seymour certainly said things during this time, we know this from reports, but there aren’t any direct quotes from her during her time as queen.

Here’s the painting mentioned, from 1545, during Catherine Parr’s tenure. Jane is on Henry’s left.

It was only after her death that Henry ‘loved’ her, but she is certain that he mourned for only for his own loss. There are reports that, during Jane’s labour, doctors advised Henry he might lose either Jane or Edward. Henry is claimed to have replied, “If you cannot save both, at least let the child live, for other wives are easily found.”

Countdown is a British television game show that revolves around word and number puzzles. It has been going for almost forty years, and is one of the longest-running game shows in the world, with over 7000 episodes.

“I saw a ghost bear kill someone, once.” Anne isn’t making this up. Supposedly, the incident occurred in 1816, when a Yeoman Warder saw a ghostly bear somewhere in the Tower of London. Terrified, he tried to stab it with his bayonet, only for the weapon to go through the image and strike the door behind it. The guard died of shock later on. A similar event happened in 1864, where two guards witnessed “a whitish, female figure” gliding towards one of the soldiers. The soldier in question charged this figure, only to go straight through it, upon which he fainted.

Elizabeth was imprisoned in the Tower of London for a little over two months in 1554, as a result of Wyatt’s Rebellion against Queen Mary. The rebellion was also the likely reason for the execution of Lady Jane Grey – both she and Elizabeth were Protestants in line for the throne, and therefore ‘more suitable’ as ruler. Both Elizabeth and Jane Grey denied any involvement, but the latter’s father and brother (also executed) were direct contributors.

“… you did die, Elizabeth was really upset about it…” Elizabeth took the news of Parr’s death badly. She refused to leave her bed, and was unable to go a mile from her residence, for five months following Parr’s passing.

Not because she liked that bearded potato man, God no… I found this deeply cursed engraving (first produced in 1544) in one of my books on the six wives, and now I want you all to suffer with me.

Anne of Cleves reacted poorly to being told her marriage would be annulled – some accounts say she fainted, others says she cried and screamed. Both could be true. The reasons given were threefold – One, the marriage was unconsummated (From testimony given by two servants, Anne thought a kiss goodnight counted as consummation – likely untrue, but this is the only reason that actually has merit). Two, Anne was precontracted to Francis of Lorraine (Untrue – the betrothal would only take effect if Anne’s father paid the dowry, and he didn’t). Three, Anne was not a virgin as claimed, based on the description of her ‘breasts and belly’, a Tudor way of saying Anne had previously given birth (untrue, and conflicts with the testimony for reason one). The annulment went through without Anne’s involvement, but (probably looking at the examples of her three predecessors) she accepted the ruling and kept herself from being banished, beheaded or otherwise.

(Other fact that has no bearing on reality – while researching Anne of Cleves, one of the pages that came up was The Simpsons Wiki. Apparently she’s the only wife who can claim the honour of having been in two episodes. :/)

Dogs don’t need to answer for their sins, they don’t have any. Katherine Howard was reportedly fond of animals in general, but had a particular soft spot for dogs.

She did the right thing. She told the truth. She died for it. Katherine Howard insisted, to the end, that she had no pre-contract of marriage to Francis Dereham. Would she have survived if she said she did?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ardenrosegarden in reply to your query: “ I'd love to hear your thoughts on Malcolm IV, most of the older sources I've seen compare him to William the Lion so I don't know a lot about him”

Thanks for this and I should apologise in advance because I feel like I ranted in a rather incoherent fashion but I wasn’t sure exactly what you’d want to know, so I sort of loosely covered everything. To be honest nobody really knows a whole lot about him (at least, not like the info we have for later mediaeval monarchs) and he died quite young (aged about 24) so it’s difficult to know what his reign would have been like if he’d been an adult for most of it instead of a child. It’s also so easy to compare the brothers- they had quite different characters and sometimes seemed like polar opposites, though they did share a lot too, especially in their aims.

One thing that really annoys me is when people use the fact that he was nicknamed ‘the Maiden’ as if that meant he was effeminate (and indeed as if being effeminate was a bad thing). This isn’t just an issue I have for Malcolm, but really applies to any situation where a word like ‘maiden’ has been misconstrued in a modern context. Maiden is *specifically* a translation of “virgo”, which nowadays we might translate as virgin instead- i.e. he is not widely believed to have done the deed (and certainly never married). Not that surprising really since, as I say, he was 24 when he died and might have suffered from chronic illness in his early twenties, and was also reputedly more pious than certain other kings, but of course 20th and 21st century writers look at the word ‘maiden’ (or even, indeed, ‘virgin’) and suddenly start sniggering, or assume that the nickname was originally meant to be pejorative- whereas it looks like it was at best a compliment and at worst a mere statement of fact.

Speaking of nicknames though, one thing I find very Interesting is the possibility that he was the original Malcolm “Canmore” (Ceann Mór) and not his great-grandfather Máel Coluim III. When noting his death, the Annals of Ulster describe Malcolm IV as “Malcolm Cendmor, Henry’s son”, whereas Malcolm III is not known to have been called that in contemporary sources- though of course the Irish annalist could just have been confused, and I (among many others) still tend to mean Máel Coluim III when I say Malcolm Canmore, since it would cause confusion otherwise (and it does kind of suit him). So firstly that raises the old problem of what we should call the dynasty those two kings belonged to (nobody knows- I tend to go with Canmore dynasty since Margaretsons and MacMalcolm dynasty looks a bit wrong to me but it’s a whole Mess and I don’t think anyone can claim to be right. The only surname which any one of the ‘Canmore’ kings seems to have used at any point was de Warenne- which is inappropriate for the whole dynasty for obvious reasons). But it also raises queries about the nickname’s meaning. Ceann Mór translates directly as ‘big head’, though one could also loosely interpret it as meaning something like ‘great chief’- and Máel Coluim III certainly suited the latter meaning at least (and maybe also the former). On the other hand, although I would argue that Malcolm IV was not obviously a ‘weak’ king, it’s difficult to see him being given an honorific for his power rather than something more obviously central to his character, like his piety.

On the basis of the Annals of Ulster (and William of Newburgh) some people have interpreted this nickname to mean that his head was literally bigger than usual, and so this has led to some theories about the nature of the illnesses which plagued him in the last years of his life. Some have theorised that he suffered from Paget’s disease. Whatever the case Malcolm is known to have been seriously ill on at least two occasions, in 1163 when he was at Doncaster and then before his death in 1165. Although these could have been isolated incidents, the evidence suggests that these illnesses had lingering effects on his strength and that Malcolm may well have been aware that he was unlikely to live long. Which, for all that we know very little about him and he was still a mediaeval monarch (with all the flaws that entailed) I do find genuinely sad. He didn’t need to worry for the succession- he had two healthy younger brothers, who, although nobody could have known in 1165, would both live to a good old age (for the time period). He also doesn’t seem to have been completely side-lined from government like some other kings either, though he may have had to take it easy in the last couple of years. But being aware that you’re not likely to last very long and that you have to pass on the kingdom in a good enough shape to a younger brother who, though loyal, had a very different and more impulsive personality, might have been quite worrying.

And then, as I say, along with his illnesses he was also quite young when he succeeded to the throne. That might not seem surprising given the later history of Scotland (of the 17 monarchs from Malcolm IV to James VI, including the Maid of Norway, 12 succeeded to the throne aged sixteen or younger), but in light of what had gone before that was quite surprising, since previously adult males seem to have been favoured as candidates for the kingship and it could be a dangerous business even for them. Even more interesting is the fact that he succeeded his grandfather without a huge amount of civil strife (though there was certainly some). For years Malcolm’s father Prince Henry had been the heir presumptive to his father David I, and had built important networks in his lands in the north of England and in Scotland. He was an adult of much experience and influence, he was well-equipped to succeed to the throne, and he seems to have been popular enough, from what little we know about him. But when Henry predeceased his father in 1152, suddenly everything was thrown into doubt. David I quickly arranged for the eleven year old Malcolm to be taken around the kingdom by the Earl of Fife, as his designated successor, but there was really no way to be sure that acts like this would absolutely secure Malcolm’s succession. There are some indications of trouble following David’s death the next year, such as Somerled’s rebellion in 1153 and the alleged treachery of a knight named Arthur in 1154, but on the whole the wider political community seems to have supported Malcolm’s right to rule and he remained on the throne (and reconciliations with men like Malcolm MacHeth and Somerled followed in later years, even if Somerled did have another go in 1164). As well as the clergy and greater nobility who had supported his grandfather, Malcolm also had his mother Ada and other family connections for support. Nonetheless the careful networks that David I and Henry had built up in the north of England seem to have collapsed upon the succession of a boy-king to Scotland and his younger brother William to the title Earl of Northumbria.

This stake in the north of England has been the cause of some controversy- historians tend either to imply that Malcolm IV was at fault for humbly surrendering the northern English lands in 1157 (when some sources would indicate he could easily have pressed his rights if Henry II had promised his grandfather not to challenge Scottish claims there, as certain English chroniclers claimed); or that his brother William was rash and petty not to accept that they were permanently lost to him (those who see Scottish history primarily as a series of failed invasions of England tend to see this as a nice moral tale). I think that both points of view vastly underestimate the complexities of twelfth-century politics, of what nobles and kings perceived their ‘rights’ to be, and indeed the complexities of dealing with Henry II of England in particular. On the one hand I could point out that Malcolm was sixteen and was not in the same position of strength re: England as his grandfather had been, so peacefully agreeing to surrender certain territories but secure acknowledgement of his rights to other areas could be seen as quite a sensible move, and on the other hand I could point out that William was sort of right to be a bit miffed about having his inheritance granted away, especially since Henry might have broken his promise. But overall it was a complex and probably difficult situation and since we definitely do not have all or even most of the facts (in contrast to later other disputes over the sovereignty of Scotland and Scottish claims) I’m not sure it should really define our views of Malcolm’s reign, even if it does tell us quite a bit about his brother’s personality.

For all that he was reputed to be pious, young, and possibly chronically ill though, Malcolm does not seem to have been an obviously ‘weak’ king either, nor did he show a complete lack of interest in war and government as some other ‘saintly’ kings are reputed to have done. We find him leading military expeditions in the years 1159-60, and he does seem to have thought of knighthood as a desirable object. Admittedly on two of those military expeditions in 1159-60 may have been in response to the dissatisfaction of his own subjects re: his support of Henry II at Toulouse (or perhaps they were just unhappy that he had left the kingdom for an extended period). He also had to deal with discontent from other key nobles- a reminder that the reports of English and Norman chroniclers regarding 12th century Scotland and its supposedly ‘saintly’ and ‘civilised’ kings may only reflect one particular view of what constituted ‘civilisation’ and successful kingship. That being said, like his grandfather David, we cannot really show that Malcolm was actively opposed to Gaelic culture and the native nobility of his kingdom, even if he might have been inclined to view the feudal ways of the Normans as the ideal way to govern. And overall, despite his illnesses and his youth, contemporary reports of his reign appear are actually largely positive and even complimentary. Perhaps this was helped out by the fact that he died young, and, again, that many of these reports come from English and French-speaking cultures (to them, Malcolm was the perfect successor to his grandfather David, and indeed in one of Kelso Abbey’s early charters they are portrayed together in a manner which echoes the biblical king David and Solomon). Although he faced rebellion from some of his chief subjects, especially those from Gaelic-speaking areas, there were also many native magnates who were supportive of him and his grandfather and it seems unlikely that they would have been seen as such successful kings otherwise (indeed, since the majority of the traditional kingdom of Scotland outwith Lothian was still Gaelic-speaking at this point, that has to count for something). Overall, I can see no reason why we shouldn’t consider Malcolm to have been a competent ruler, even if I wouldn’t necessarily describe him as successful like grandfather or some of Scotland’s later monarchs.

I do apologise for this screed of vaguely incoherent info- I am genuinely interested in Malcolm IV but haven’t had to think about his reign in any depth for a while. Lack of evidence and his early death prevent us from making any deeper assessment of his character and reputation, but I’ll round off with some quotes from contemporary and later sources about him that might give a much better idea of how Malcolm IV was viewed than any of my ranting can. Although obviously the full versions of some of these chronicles are online too (and are worth checking), I’ve quoted mostly from A.O. Anderson’s collections ‘Early Sources of Scottish History’ and ‘Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers’, since these sourcebooks are also really good starting points if you’re curious about any further aspects of Malcolm and William’s careers (you can always ask me, but obviously my view is always subjective). William of Newburgh is a major source for Malcolm’s reputation imo though and the Chronicle of Melrose covers some of the Scottish aspect- and there’s always the anecdote of Ada de Warenne allegedly trying to sneak a girl into Malcolm’s bed which is... dodgy to say the least, but probably meant to show how ‘saintly’ he was and was perhaps also a callback to figures like his distant kinsman Edward the Confessor. Overall though, if Anglo-Norman chroniclers wanted to wax lyrical about the ‘saintliness’ of Scottish royals, and David I and St Margaret weren’t available, Malcolm seems to have been the next best thing.

“Malcolm Cendmor, Henry’s son, the sovereign of Scotland, died: with regard to charity, and hospitality, and piety, the best Christian of the Gaels to the east of the sea.” - The Annals of Ulster

“To the king of Scots also, who possessed as his proper right the northern districts of England, namely Northumbria, Cumberland, Westmoreland, formerly acquired by David, king of Scots, in the name of Matilda, called the empress, and her heir, [king Henry II] took care to announce that the king of England ought not to be defrauded of so great a part of his kingdom, nor could he patiently be deprived of it: it was just that that should be restored which had been acquired in his name.

And [Malcolm] prudently considering that in this matter the king of England was superior to the merits of the case by the authority of might, although he could have adduced the oath which [Henry] was said to have given to David his grandfather (...) restored to him the aforenamed territories in their entirety, and received from him in return the earldom of Huntingdon, which belonged to him by ancient right.”- William of Newburgh

“These are the ones who survive from that holy generation. From the Empress Matilda you came, most illustrious man, whom we now hail as Duke of the Normans and of the Aquitainians, Count of the Angevins, and truly heir to England. Your brothers are Geoffrey and William, of whom we hope for good things, to whom we wish the best. From Queen Matilda and the devout King Stephen came William, count of Warenne and Boulogne. From Henry came Malcolm, William, and David, heir to his grandfather’s name. May God have mercy on their childhood and may you too be merciful, whom divine-loving kindness has established as the most noble head of your whole people. May your holy gaze, your loving heart, and your effective action be upon them in all their necessities. They are orphans, left to you by their grandfather, who loved you above all people; you will be a helper to these your wards, for you are in age more mature, in hands stronger, and in feeling more experienced than they.” - Ailred of Rievaulx’s appeal to the young Henry II in his ‘Genealogy of the Kings of the English’- naturally there is quite a bit of hyperbole in this and I do have to suppress the urge to react to it with “Lol” every time I read it. This quote is not taken from one of Anderson’s books.

“About this time the most Christian king of the Scots, Malcolm, of whom we have made mention, as was fitting, in the preceding book, upon Christ’s summons put off the man, to be associated with angels; and lost not his kingship, but changed it. A man of angelic sincerity among men, and as it were an earthly angel, of whom the world was not worthy, the heavenly angels snatched him from the world. A man of wonderful gravity in tender years, of astonishing and unexampled purity upon the summit and in the delights of the kingdom, he was taken from a virgin body to the Lamb, the Virgin’s son, to follow him where he should go.

Clearly he was taken away by an early death lest the wickedness of the times should change his marvellous innocence and purity since so many opportunities and incentives drive astray a young man on the throne.

But because among the tokens of virtue were not wanting in his admirable soul some small stains resultant from royal delights which nevertheless he rather endured than enjoyed, a visitation let fall, not sent down, from heaven chastisted him with paternal lash, and refined him to purity. For before his death he so languished for several years, and besides other sufferings endured severest pains in his extremities, that is his head and feet, that any repentant sinner would seem capable of being cleansed to pellucidity by so great flagellations.

(...)

His brother William succeeded him; a brother, indeed, as it appeared, readier for the uses of the world, but not to be more fortunate than he in administration of the kingdom.

The world which his brother wished to use simply, and for that cause piously and laudably, [William] purposed not only to use but to enjoy; and striving much to exceed his brother’s measure in temporal excellence, he yet could never equal his glory even in temporal felicity.” - William of Newburgh again, who seems to have been a bit of a fan.

I’d personally like to find out more about what any surviving Gaelic sources might have thought but that will have to wait. On the whole though, while I’m not convinced that Malcolm was the perfect angel some sources make him out to be, I can at least say with absolute certainty that he doesn’t give me the Fear like Alexander II has somehow managed to do from beyond the grave.

(David I and Malcolm IV, portrayed in 1159 in a charter from Kelso Abbey. The initial they are sitting in is ‘M’ and is the start of Malcolm’s name)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 125: Hadrian’s Wall and the Scottish Borders

When we first started planning this trip, one of the big sites I'd wanted to see was Hadrian's wall. But it's so far from anywhere else we wanted to go in England that I had resigned myself to the fact that I probably wouldn't get to go. Luckily, Rabbie's offers a tour of the wall from Edinburgh. Not only would we get to see Hadrian's Wall, we'd get to approach it from the north like an old Celtic barbarian.

It was a long tour, so we had to get up and into town early.

There must have been quite the party going the night before. Even the statues woke up with traffic cones on their heads.

Our guide and driver for the day was Nik, a middle-aged, born-and-bred Edinburgh man with the accent and stories to prove it.

As we drove south, we passed through the beautiful rolling hill country that makes up the Scottish Borders. The Highlands are seem to get all the glory when it comes to romanticizing Scottish countryside, but the Lowlands definitely have their own idyllic charm.

Nik told us some interesting stories about the medieval residents of the Borders and their complex relationship between England and Scotland. They were ethnically Scottish, but the Borderers resented both countries because their wars inevitably brought the razing and pillaging of border towns by both sides.

The Borderers were excellent horse riders and highly valued as mercenary cavalrymen throughout Europe. Whenever the English and Scottish armies fought in the Borders, the Borderers would hire themselves out to both sides, then sit on the sidelines of each battle until the winner was clear. They made special coats with English colors on one side and Scottish colors on the other, so they could flip their coats inside-out to match whichever side they decided to be "fighting for" at the moment. Hence the term "turncoats."

When they weren’t fighting as mercenaries, the Borderers spent a lot of time fighting themselves. One town would gather a raiding party and invade the next town over. That town would then gather a counter-raid to get their stuff back. Eventually, the raids became so bad that towns hundreds of miles away–well outside the Borders--were being raided by these crazy hill people. Neither country wanted to take responsibility for them, but when King James VI and I united Scotland and England under one crown, he was able to raise a police force to move in and establish order.

We also saw a lot of sheep on our drive. According to Nik, there are three sheep in Scotland for every man, woman, and child. Which is the perfect number, he said–one for meat, one for wool, and one for snuggling.

Our first stop was the abbey town of Jedburgh, just ten miles north of the border with England. Streamers hung up all over the town indicated that a festival was going on, but it was dead quite on this Thursday morning.

The abbey, like most abbeys in Britain, is only a picturesque ruin now. But this time it wasn't Henry VIII's fault--the Scottish destroyed their own abbeys during their own Presbyterian Reformation.

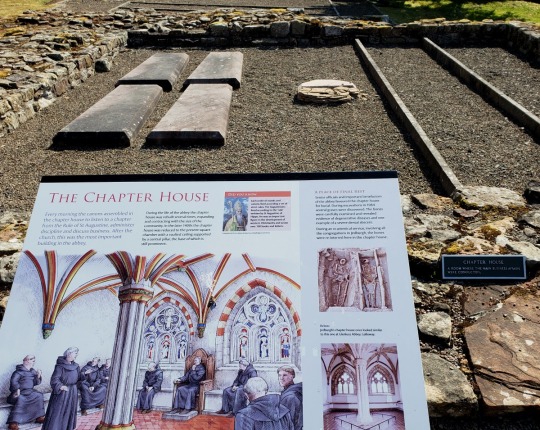

Before its destruction, the abbey was inhabited by Augustinians, who were known as cannons rather than monks. Whereas monks live and work in their abbey, cannons are priests who choose to live communally in an abbey but still teach and perform services in their local community.

We got about an hour to explore the small museum and wander through the peaceful ruins.

Next we headed down to the crossing between England and Scotland, where we pulled over for a quick photo op. There's no security or anything, just a pair of engraved standing stones.

The view was fantastic, though.

Our timing was good, too. Just as our group finished taking pictures, a kilt-clad busker showed up to serenade us with his bagpipes. More oddly, a man driving through the parking lot stopped and called one of our group mates over so that he could give her some sort of "helpful" pamplet. According to Nik, this guy is a regular feature at the crossing who stages this sort of thing all the time, making it seem like he's just a friendly local who randomly decided to pull over and give the handout to a passing tourist.

After a few very pleasant hours of driving (some of which my dad and I might have spent dozing), we arrived at Hadrian’s wall. Specifically, we arrived at Steel Rigg, a dramatic line of glacial crags that the wall runs along the top of.

It was a steep climb up to the top of the outcrop, but the view was well worth it. Even if the wall was never really used as a defensive installation, it was easy to imagine hordes of painted Celtic barbarians massing to the north.

And seeing the way crags rise up like a wall themselves, I can very easily understand how George R.R. Martin was inspired by this place to create his fictional wall of ice in A Game of Thrones.

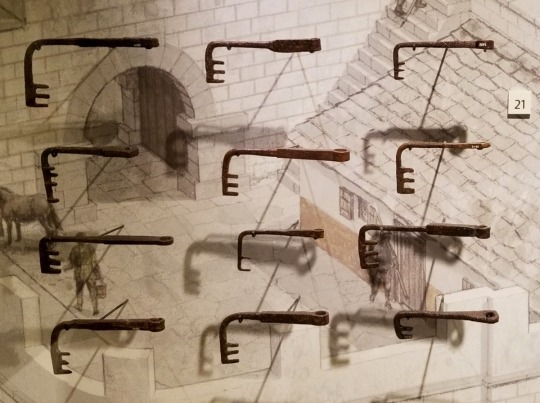

Next, we went to the nearby Vindolanda excavation and museum. Vindolanda was a Roman walled settlement inhabited by the soldiers who manned Hadrian's wall, as well as their families and the various merchants and artisans who supplied them. The site has been meticulously unearthed, and the included museum is filled with fascinating artifacts from the Roman inhabitants’ everyday lives.

There was pottery, flatware, tweezers, and lots and lots of leather shoes. The Romans wore very intricate leather shoes, but apparently very few examples are still around. Vindolanda is a treasure trove of leather and wooden goods because the land it's on is basically a bog--pretty much the same story as with the Celtic artifacts we saw at the Irish National Museum of Archeology in Dublin.

Despite being such innocuous pieces, one of the collections that struck me the most was the wooden barrel staves on display. We could see the ancient branded markings in old Latin clear as day, and one stave still bore a round stain from when some Roman set something dirty on it. The world's oldest coffee ring, perhaps?

There was a fascinating collection of Roman locks and keys that were much more intricate than what I would have assumed they had at the time.

Other interesting finds in the museum included a piece of intricately painted glass that had been imported from Roman Germany, some surprisingly shiny Roman coins a bug-resistant wig made from local moss, and a small metal hand used for religious ceremonies.

But the pride of the museum's collections was a barely distinguishable pair of leather boxing gloves. Boxing was a favorite pastime in the Roman Empire, and there are countless artistic depictions of soldiers and gladiators wearing an ancient form of boxing gloves. But these gloves found at Vindolanda are the only known surviving pair in the entire world.

Normally, there is an afternoon guided tour of the ruins, but today's tour was replaced with a performance by a group of local Roman Legion reenactors.

They described their arms, armor, and troop composition. We learned that up until the mid-20th century, historians didn’t actually know for sure how the iconic Roman segmented plate armor worked. It wasn’t until an old wooden chest under someone's house was discovered to contain two intact sets that people were able to accurately recreate them. And by recreating them, historians and reenactors can learn firsthand how they work and would likely have been used.

And you know you're in for a treat when your tour guide is excitedly taking pictures along with the rest of the group.

We learned how most of the soldiers manning Hadrian’s wall would not have actually been Legionnaires, but rather auxiliaries. Auxiliaries were non-citizen soldiers who fought for the Roman army in exchange for citizenship after 25 years of honorable service. In the meantime, they got less money, worse equipment, and more dangerous postings.

The reenactors also described how the invincibility of the Roman army was not just due to the superiority of their arms and armor. At the time, the Romans basically reinvented the idea of a professional, standing army. The Celts of Scotland had a proud and fierce warrior culture, but they didn’t really have armies. When one clan went to war against another, they would just gather all the able-bodied men together and head out. They were strong and fierce, but they just didn’t have the skills and tactics that full-time soldiers are able to develop through years of constant, structured practice.

We got to see the reenactors charge, duel, throw spears, and even fire a ballista (basically a giant crossbow, for anyone who's never played Age of Empires).

Leaving Vindolanda, we headed back up to Edinburgh through the western Lowlands. Again, the rolling hillsides were spectacular. I was especially enthralled by the area around the River Tweed, the home of a famous British textile. We could easily see how the raiding parties Nik described could hide out in a fog-cloaked ravine and become virtually unfindable. Nik also pointed out the particular hillsides where the wild haggis love to run free--in circles, of course, because of their naturally lopsided legs.

We also passed by the narrowest hotel in Britain.

Back in Edinburgh, we finally got my dad his first taste of Nando's before heading back home. It was in a shopping mall at the edge of Old Town, and it was about an hour's wait between when we first put our names down on the waiting list and when we actually got our food. It was well worth it, though--especially considering that it would be our last Nando's of the trip.

Back home, we rested up and prepared ourselves for our last two days in Edinburgh. We would be staying in the city, and we had almost all of it left to see.

Next Post: Edinburgh, Part 2 (History, Hiking, and Beer)

Last Post: Glasgow

#180abroad#edinburgh#scotland#lowlands#scottish borders#hadrian's wall#vindolanda#ancient#rome#roman ruins#history#travel

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shetland has two castles both of which date back to the time when the Isles were ruled by Earls. Even though both castles are in ruins, there’s enough left of each one to make them fun to explore.

I’ve been to them both several times now and each time I go back I feel surprised by how much of them there is left once you get inside. With both castles, but especially Scalloway Castle, I always get the feeling that they’re bigger on the inside. Now where have I heard that before?

Scalloway Castle – it’s bigger on the inside

Here’s a bit of history. I promise you won’t be confused. (But if you’re really not a history lover just skip the orange bits.)

In 1533 King James V had a son with his mistress Euphemia Elphinstone (what a fabulous name!). They called him Robert Stewart. In 1542 he had a daughter with his wife. They called her Mary Stewart. Six days later the King died and Mary, as his only legitimate child, succeeded to the throne despite being less than a week old.

When Robert Stewart got older he was given land in Shetland and Orkney. This wasn’t enough for him and he seized more land and misused taxes. Of course this led to lots of complaints. In a way that doesn’t seem that different in politics today, despite the complaints he was made Earl of Orkney and Lord of Shetland. Eventually the local lairds (landowners) managed to get his Earldom revoked.

In the meantime Robert had got himself a son and so had his half-sister Mary. Robert’s son was called Patrick and Mary’s son was called James. Patrick didn’t get on with his dad but did get on with his Auntie Mary (who was now Mary, Queen of Scots) and cousin James (who was to become both King James VI of Scotland and King James I of England) and so was given his deposed dad’s titles.

As well as his Auntie Mary, Patrick also had an uncle called Laurence Bruce. Laurence was a half-brother of his dad though not related to King James. To recap, Robert and Mary shared a dad (James V) and Robert and Laurence shared a mum (Euphemia). Laurence was appointed sheriff and chamberlein of Shetland in 1573. He also abused his position and only lasted four years before he was sent back to Scotland with the 16th century equivalent of an ASBO banning him from ever stepping foot in Shetland or Orkney again.

Yeah, right. Twenty years later he was back. And not quietly. In 1598 he returned and got himself a castle built on Unst, the most northerly isle in Shetland. Meanwhile Patrick was on a bit of a land grab which didn’t go down well with his Uncle Laurence and they were at loggerheads.

Patrick decided he needed a castle of his own and got one built in Scalloway on the Shetland Mainland. To get one up on Laurence he also decided to get a palace built in Kirkwall in Orkney. He didn’t actually need either as he mostly lived in the palace in Birsay in Orkney and usually had a representative looking after his affairs in Shetland.

Patrick’s castle in Scalloway was built using unpaid labour. He basically commandeered the local lairds’ tenants and didn’t even offer food or drink in return. You can imagine how well that went down. He also claimed all the driftwood that was washed ashore for use in his building project. In a place with very few trees, driftwood was the main source of wood and so denying people access to it was grossly unfair. There were lots of rumours and complaints about the evil Patrick and it was said that he was using blood, eggs and human hair to build his castle. This was probably true as these ingredients were often used in building in those days.

Finally, in 1609, the lairds had really had enough of Patrick. At last their complaints were heard and he was taken to Edinburgh Castle where he was imprisoned. He was executed in 1615, though not because of his behaviour with the castle building, but for treason. He had been encouraging his son Robert (not to be confused with his dad, Robert) to take over Orkney.

With the demise of Patrick things changed in the Isles. Shetland and Orkney had originally belonged to Norway and had been given to Scotland as part of a dowry. Though they were now Scottish they had still been ruled using the old Norse legal system. With the Scotland Act these ‘foreign laws’ were abolished and the legal system was brought into line with the Scottish system. This was not necessarily a good thing as the Norse laws had been more precise and less susceptible to interpretation.

Okay, so I lied about it not being confusing. Even though I’ve read lots about this, I’m not convinced I properly understand it all myself. If anyone would like to correct me on anything then please feel free to drop me a comment below.

The castles didn’t last long after this. Muness Castle in Unst (Laurence’s castle) burnt down in 1627. Scalloway Castle (Patrick’s castle) fared little better. It was used to house troops in 1653 and by the early 1700s was said to be in poor repair.

Muness Castle

The entrance to Muness Castle. It’s roofless and some of the floors are missing, but the outer walls and towers are still standing.

Muness Castle is found by following the road round from Uyeasound. If you want to walk it’s a couple of miles from Uyeasound, but quite a pleasant walk on a nice day and you do pass an interesting 3m tall standing stone along the way.

Looking back towards Uyeasound village from the Clivocast standing stone on the road to Muness Castle.

At the entrance to the castle you can find a box with torches (that’s flashlights to my American readers), but they’re often not that good so you’re better to bring your own or use the light on your phone.

Looking out to sea from Muness Castle. I do like the rope topping along the wall.

Uyeasound (the body of water by the castle, not the village with the same name), was once an anchorage for ships trading between Shetland and Leith in Scotland. There would also have been ships and trade from Bremen in Germany and it’s thought that most of the castle’s furniture would have come from there.

Of course a castle this fine had to have a pretty well-stocked wine cellar.

Sketches on the information boards inside the castle give an artist’s impression of how it’s thought the castle would have looked in its heyday. The walls in the smaller rooms would have been panelled, in larger rooms colourful tapestries would have been hung on the walls. The ceilings would have been painted. The furniture would have been top quality and there would have been plenty of fine silverware displayed.

Upstairs in the castle – there are information boards throughout.

It was first and foremost a castle though, and so had plenty of gunholes and turrets and a couple of towers. From the towers the gunners would have been able to see anyone coming no matter which direction they were coming from.

Looking out to sea

You can explore the castle on several levels, up and down different staircases. Other staircases are closed off as they’re too dilapidated to use today.

Some of the stairs are well past their use by date.

Parts of the castle are completely dark – some of the corridors and small ground floor rooms for example – and this is where you’ll need your torch. On the upper levels you won’t have a problem with the light because of the missing roof.

This corridor was pitch black – it’s why you need a torch.

If you look at the walls around you, you will be able to see the remains of fireplaces and the lines of holes in the walls where the joists for the upper floors and ceiling would once have been.

Here you can see the outline of the original fireplace and the where the joists for another floor would have slotted into the walls.

You can easily spend half an hour exploring this castle and more if you read all the information. There’re a couple of parking spaces in the nearby layby and it’s not too far to walk to a very nice beach.

Scalloway Castle

Scalloway with its castle in the centre.

A word of warning here. If you are planning to drive to Scalloway to visit the castle and you’re coming on the road from Lerwick, you need to have your wits about you (and very quick reactions). You arrive on the hill above Scalloway a lot sooner than you might expect. As you drive up the hill and reach the top the road bends to the right at a complete 90° angle. At the same time the view opens up and you get your first view of Scalloway and its castle.

The view is stunning and absolutely breath-taking (the photo above really doesn’t do it justice). To go back to what I said about needing your wits about you – these really could be your last breaths as the view takes you by surprise and puts you in danger of sailing straight ahead right over the cliff edge. Even though I’m expecting it, the first time I see it on each visit my reaction goes something like this:

Wowwww (complete astonishment, head moves forward, eyes widen)

Eegghhh (complete panic, head goes back, hands grip steering wheel, body tenses)

AAARRGHHHH (I didn’t know my van could fly!)

Actually I’ve never got to the AAARRGHHHH bit because I’ve always pulled my steering wheel round to the right with about half a second to spare. But do take care.

Scalloway Castle seems taller and more tower-like than Muness Castle, though it’s thought the same master builder, Andrew Crawford, was responsible for both.

The castle originally had four stories. Like Muness, its outer walls still stand but its roof is long gone. Some of the ornamental stonework is missing as it was taken to be used in other buildings during the 18th century. Excavations have revealed that there would have been additional outbuildings to the north of the tower, but these can’t be seen today.

Collect the key from the museum and you can open the door and pretend you live here.

To get into this castle you need to collect a key from the Scalloway Museum which is next to the castle and well worth a look.

Look for the inscription over the door – you won’t be able to read it, but look for it anyway.

Before you go in look out for the inscription over the door. It’s impossible to read today, but according to an 18th century record it says, “Patrick Stewart, Earl of Orkney and Shetland. James V King of Scots. That house whose foundation is on a rock shall stand but if on sand shall fall…”

The castle is L-shaped with a main rectangular shaped tower and a smaller square wing. The ground floor housed the kitchens and stores as well as a well.

Follow the corridor and check out all the rooms leading off it.

As Scalloway was the original capital of Shetland, this castle was used as the thing (Norse word for parliament) during Earl Patrick’s time. Court sessions were also held here and there was a room in which prisoners were kept whilst awaiting their trial.

There is plenty of information about the castle and the Earls on the walls on the ground floor.

Even though Patrick had lots of inherited debts he had very extravagant tastes and this castle would have looked pretty fancy back in the day.

Notice the partially glazed windows.

The walls would have been covered in tapestries and the huge fireplaces would have a cast a flickering glow as well as providing light. The windows were partially glazed, but glass was expensive even for an Earl with extravagant tastes so the lower parts of the windows would have been covered with wooden shutters instead of glass. Obviously this blocked the light.

Although some floors are missing it is possible to get upstairs in parts of the castle.

The fireplaces burned through so much peat that the local tenants were required to provide peat as part of their rent. Rent was also collected in the form of a low-grade butter used for lubrication, fish oil which was mostly used for lighting and wadmel which is a rough form of cloth. These items were also collected for taxes which were meant to be passed on to the Crown. The goods, once collected, were sold to the German merchants who would visit Shetland each year.

You could do with a torch in this castle too.

The main staircase leads up to what was the great hall. Small spiral staircases in opposite corners led up to the Earl’s private quarters. On the top floor were rooms for guests each of which had its own fireplace and latrine.

Scalloway Castle from across the bay

Both castles are really worth a visit and it’s nice to see them both so you can compare. They are both free to enter as well. Muness Castle can be visited at anytime, but because you need the key for Scalloway Castle you can only get in when the museum is open (though you can wander round the outside at any time).

So what do you think about this tale of two castles and the tales of the Earls? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Like this? Read these next:

Cute Houses of Scalloway Lerwick vs Kirkwall Shopping and Eating in Lerwick

Pin it

A Tale of Two Castles. New post with an outline of Shetland history and help to plan your visit to the castles. Shetland has two castles both of which date back to the time when the Isles were ruled by Earls.

0 notes

Quote

It is often thought that the systematic provision of schooling in Scotland began only at the Reformation but this was not the case. The song schools discussed in the previous chapter, which educated the choristers at cathedrals, abbeys, collegiate churches and some parish churches, were part of a much wider network of medieval Scottish schools. Schools providing basic tuition in reading and writing were often attached to parish churches or monasteries and staffed by chaplains or monks. In many burghs, grammar schools provided boys with the education required for university entrance and the masters there were clerics too, usually secular priests. The Dominican friars, whose houses were invariably in urban centres and whose order had a special vocation for preaching and teaching, perhaps provided the masters for some grammar schools, such as those at Ayr and Glasgow, but more commonly they seem to have focused on educating their own postulants and novices, often to very high standards. There were even some 'sewing schools' for girls in a few burghs, although by the 1620s, the Kirk was getting suspicious that they were nests of 'papistry'. Before the Reformation, there were schools for girls from elite families in nunneries such as Elcho, Aberdour and Haddington, though women could not progress to university at this period. We know of the existence of about a hundred Scottish schools of various types before 1560 and there were certainly many more which have escaped the documentary record. Amongst the most difficult to identify are the informal 'household' schools which formed in the homes of the landed elite: private tutors would have been engaged to educate the sons and wards of the household along with other boys who were often fostered from families with ties of kinship or clientage. For example, John Carswell, future superintendent of Argyll and bishop of the Isles, was employed in the 1550s by the 4th earl of Argyll as tutor to the future 5th earl, in whom he instilled fixed evangelical views. In some households, girls were educated too. For example, the daughters of Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington were highly literate and cultured, and Marie seems to have been an accomplished poet (...). The education provided in these domestic schools depended entirely on the quality of the tutor but could be very advanced. One of the finest Scottish humanists, George Buchanan, served as tutor to the young third earl of Cassilis, then to an illegitimate son of James V, and later to King James VI. Some of the burgh grammar schools also reached very high standards. For instance, the famous Protestant academic, cleric and controversialist Andrew Melville had been educated before the Reformation at the grammar school of Montrose, where he learned to read Greek, and the schoolmaster at Dunfermline in the 1470s and 1480s was Robert Henryson, the learned and distinguished poet. For much of the period, the standard textbooks for Latin grammar used in Scottish schools were those of Aelius Donatus (a Roman writer of the fourth century) or Johannes Despauterius (a Flemish humanist, d.1520). However, there was also a native Latin grammar written by John Vaus of Aberdeen, first printed in Paris in 1522 and reprinted in Edinburgh in 1566. In 1533, George Buchanan translated Thomas Linacre's Rudiments of Grammar from English into Latin and this became a 'bestseller'. After the Reformation, a flurry of new native grammars appeared. Scottish schooling could thus easily stand comparison with the provision made in other countries of the period. The humanist idea that the promotion of lay education was of public benefit was most clearly encapsulated in the 1496 Education Act, which stipulated, 'that all barons and freeholders that are of substance put their eldest sons and heirs to the schools from the age of eight or nine years, and to remain at the grammar schools until they be competently founded [educated] and have perfect Latin. And thereafter to remain three years at the schools of arts and law [at the universities] that they may have knowledge and understanding of the laws. Through the which Justice may reign universally through all the realm...' (...) The act was supported by James IV, but is usually ascribed to the influence of William Elphinstone, as already mentioned. Elphinstone had just established his new humanist university at Aberdeen with faculties of arts and law (amongst others) and if it were not for the face that he is invariably regarded as a high-minded and sincere reformer, the act might be interpreted as a private recruitment drive. The new law was never systematically enforced, but it promoted important principles and was unusually enlightened for its time: there was no comparable legislation in France or England. (...) Thus the official focus on Scottish schooling after the Reformation did not establish an education system from scratch, but rather tried to extend and improve existing provision and to infuse Protestant doctrine. Taking some inspiration from the educational decrees of the Catholic Council of Trent but also building on the model of Calvin's Geneva, the First Book of Discipline of 1561 envisaged a primary school in every parish, with 'schools of full exercise' (grammar schools) in the major burghs. It also insisted that the education of the poor should be paid for out of public funds. Lack of financial support meant that the vision was never fully implemented, but by the 1630s there were about 800 schools of various types across the country. Scotland had a school system that was impressive by international standards and which had fostered one of the most literate societies in Europe.

“Glory and Honour: the Renaissance in Scotland”, by Andrea Thomas

Ok I would feel guilty about quoting so much of this book if it weren’t for the fact that it was hands down, my best purchase of 2017. It is a lovely glossy coffee table book, a handy reference guide, and a fascinating read all at once, and is an absolute must for anyone who has an interest in either the Renaissance or Scottish history.

After all what better than to study the impact of such an important period as the Renaissance than to look at its effects on a small, relatively poor country on the edge of Europe, with a population of about 500,000 and only middling significance at most, but which was nonetheless was fully keyed into European cultural and social movements, and managed to produce some really impressive figures and institutions for a country of its size?

BEST. PURCHASE. 2017. HANDS. DOWN.

Perfect summer reading.

(But please don’t take the quote as the author’s whole argument- there are bits I cut out. Also there is less focus on the Gaelic side of things than I would like- but the author does argue that well, saying that Gaelic culture produced some beautiful art but it rarely fits into the specific cultural movement of the Renaissance, and belongs to a different world- though admittedly some of the most important figures of the Renaissance in Scotland, George Buchanan for example, were Gaelic speakers, their contributions just tended to be in Latin or Scots. And tbh even if more work does need to be done on the Gaelic side of things for the Renaissance, at least this book is a start and a good compendium for Scotland as a whole. I doubt that I’ve explained that well but nonetheless.)

#Renaissance#Scottish history#Are there things it leaves out? Yes of course but it is impressively comprehensive#It's both a great introduction AND of academic importance#And it's a study that has been sorely lacking for decades despite there being MORE than enough material#books

8 notes

·

View notes