#doomed megalopolis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

CLAMP's legacy as originally starting from doujinshi circles is really fascinating and makes a lot of sense when you understand that a lot of their manga are just straight up loose adaptations or spiritual reinterpretations of some of the most iconic pieces of 20th century japanese fiction, especially literature.

In many ways a lot of their storytelling is best described as "derivative" but I don't really like using that word because it has such a negative connotation. I think CLAMP's genius is actually their ability to iterate on the themes and ideas and character types and other inspirations that they derive from, especially in their ability to translate those elements to a visual/aesthetic format and to add themes of queerness into those stories or highlight the already present elements of queerness.

Like Tokyo Babylon is inspired by Teito Monogatari (and also Peacock King but that in of itself is a subject for a whole other post). And it's not just limited to the quick one-off comedic reference to Yasunori Katō that we see in the beginning of the manga. The title itself is a reference to the first manga adaptation of the Teito Monogatari. And that title choice for the adaptation was itself probably a combination of a deliberate reference to the Book of Revelation which was culturally relevant in Japan at the time for reasons I'll explain in a little bit, as well as the fact that the author of Teito Monogatari based Katō in part on Aleister Crowley. But Teito Monogatari and Tokyo Babylon are fundamentally stories about the exact same subject matter, that is the City of Tokyo itself.

X aka X/1999 is pretty self evidently a loose adaptation of the Digital Devil Story novels, the ones that would go on to be adapted loosely into the Megami Tensei video games. An apocalyptic battle for the fate of the entire world fought in Tokyo between two ideologically opposed groups of super powered beings, one of which is literally called The 7 Angels. There is a magic sword associated with the death of a female loved one, there are references to a whole bunch of religious and occult concepts from both the east and west, and one of the key locations for the plot is an elite private high school. X and DDS/ Megaten are both quintessential examples of media born from the Japanese Occult Boom. Bad Japanese translations of the prophecies of Nostradamus in the '70s that inspired the Book would become mixed with the social and economic chaos that was the Japanese asset price bubble and other late stage capitalist nonsense and then the financial collapse in the '90s is why you have in both Tokyo Babylon (and by extension the manga adaptation of Teito Monogatari) and X this weird obsession for the Book of Revelation in a ostensibly non-Christian cultural zeitgeist. Tokyo was both "Babylon" as in Rome or any sort of other hypothetical city / civilization that represented decadence and degeneration, and it was Tel Megiddo in the sense that it was the place where the end of days and the battle heralding the Apocalypse would commence.

And then Gate 7 is literally just one of dozens upon dozens of fanfic/ rip-off / adaptations of / works inspired by Makai Tensho which came out in the '60s and sort of is kind of the cultural grandfather of novels like Digital Devil Story, Teito Monogatari and the Onmyoji series. It's the modern source of basically every piece of Japanese pop culture that treats the notable historic figures of the Warring States Era as more than just badass warriors but literal demigods, sorcerers and super powered beings. Mirage of Blaze(which also has some pretty clear inspirations from Tokyo Babylon and it sort of exists in a trifecta with TB and Yami no Matsuei in their relation to the Onmyoji novels by Baku Yumemakura but again, that is the subject for another post), Samurai Warriors and Sengoku Basara, pretty much all of the Fate series but especially the original Stay Night and especially especially Redline/ GudaGuda and Samurai Remnant, and a whole bunch of fighting games and Ninja OVA'S are all examples of Makai Tensho's influence.

#CLAMP#clamp#tokyo babylon#x manga#x/1999#gate 7#teito monogatari#doomed megalopolis#digital devil story#shin megami tensei#megaten#makai tensho#fate series#fate stay night#fate samurai remnant#sengoku basara#samurai warriors#japanese occult boom#media analysis#peacock king#onmyoji#bl manga#clamp manga#manga#sci fi novel#yami no matsuei#honoo no mirage#mirage of blaze

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some times you see a photo with so many bizarre things in it that you overlook the weirdest parts. What are we even looking at? A flood in China? Is this a movie set? Who is this woman sitting on the half-submerged car?

But then, suddenly, I realized what I wasn't seeing, which was this curious person, calmly standing in the middle of the giant heap of cars, perhaps dressed in what looks like a 19th century Lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese Army? What does that remind me of?

For me, it is Yasunori Katō, the villain in Hiroshi Aramata's Teito Monogatari (帝都物語) from which we get the Doomed Megalopolis franchise.

Of course, it isn't. The photo is of the 1966 flood in North Point, Hong Kong, which dumped over 15 inches of rain in 24 hours. The storm resulted in widespread flooding, landslides and, "turning streets into raging torrents that killed at least 50 people ... causing cars to be swept down roads like toys."

In the series, set in Tokyo, Yasunori Katō does indeed attempt to use his supernatural powers to set off a natural disaster in order to destroy the city (in this case it is The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923) and since cosplay wasn't a thing back then I probably will never get a satisfying answer as to why this person is so weirdly out of place.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

No cap fire ass anime 🌞🌝⭐

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Long-Winded, Amateur Animation Cel Tutorial

I'll be going through the step-by-step process of how I made a replica animation cel, complete with a background and frame, listing the materials, while explaining the many, many blunders I made along the way so that if you attempt something like this, you'll hopefully have an easier time at it than I did.

For the most part, I didn't want to buy new materials, and instead wanted to mostly use what I currently have available, so this method is probably not very suitable for selling original works in the animation cel style that'll last a long time, this is just meant to be for fun for now, so I didn't buy any fixatives or respirators or transparency film packets. If you want to learn more about that stuff to sell cels, @yamino has tutorials. If I were inclined to sell my own cels, I’d rather sell original works rather than replicas.

There is a company called Chromacolour that sells animation supplies like cel sheets and cel paint, but that stuff is pricey, and I'd have to account for international shipping. So, all the materials here can be bought at many of the usual art stores you might use.

Let's get into it... (WARNING: Very long, I'm trying to be thorough!)

Getting Your Reference

The screenshot I chose to recreate was of the villain Yasunori Kato from the anime Doomed Megalopolis:

This was attractive to me for a few reasons. 1. I love the effect of gaps being left in parts of the cel where some of the shadows are on the cape and face, letting the background come through, it's sick af. 2. Besides the sweat drops, badge/medal, and eyes, there weren't a lot of tiny areas that I would have to be especially careful about filling in. If you're just starting out, whether you're doing a replica or something original, pick something that doesn't require a whole lot of precision.

Also, if you're doing a replica, get the highest quality image you can for your reference so you can clearly see the linework and the colors. The best one I could find for this screenshot wasn't particularly great, this wasn't an HD transfer, but it was good enough. If you can find a picture of the actual, original cel for your reference, or something very similar, that would be helpful in getting to see the colors in their natural state, but it's not required.

If you're doing something original, this first step entails doing a drawing and filling in the colors so you have a game plan.

Line Art

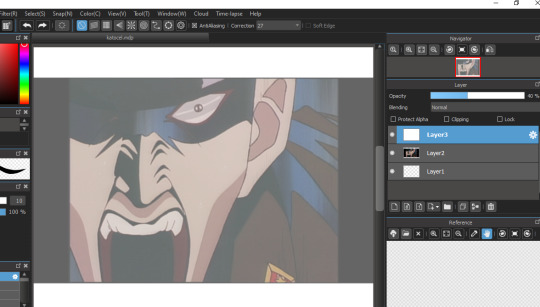

Here's where things started to go off the rails for me. My original plan was to trace the lineart in my drawing program of choice onto a semi-transparent layer, then increase the opacity to 100% after I was done drawing the lines, then print out the lineart onto a piece of paper so I wouldn't have to use up a lot of ink. My setup was this;

(As you can see, I flipped the image, I'll explain why I did that in a little bit) Then, wouldn't you know it, I found out my stylus's battery died and I didn't have any more. I didn't want to wait to buy replacements before continuing, so instead I trucked ahead with another method, printing out the image on a piece of copy paper. Unfortunately, some of the details were lost in the printing, so when I traced the lines, I had to have my original reference picture on my computer off to the side and just guess where those details were supposed to go. Maybe I should have played around with filters before printing to increase the contrast, hmmm..

If you have a tablet or ipad that's big enough, you probably wouldn't need to print the reference picture out first, and instead make the image the size you want, lock the screen in place if you can or wear a glove, put a piece of paper over the screen, and trace it that way, but I didn't think of that at the time i was doing it... But if you don't have a tablet/touchscreen laptop/ipad, or if your image is too big, then you'd have to print your reference out anyway.

I first traced the lines onto a piece of regular paper the way I would have done it digitally if I had been able. I didn't want to jump straight into putting the lines onto the cel just yet because I wanted to make sure I was satisfied with them and avoid having to make big changes on a cel sheet. I shaded some areas blue or yellow as a reminder to myself which areas are not part of the black shading which will be put in later.

I hear some of you asking "Why didn't you use transfer film to put your lineart onto and skip these extra steps?" I'm gonna be real with you guys, I didn't know what transfer film was until after I bought my acetate paper and I don't want to buy anything else for making cels right now unless I choose to make this a regular thing.

For those who don't know, transfer film allows you to print stuff onto a clear paper a la the Xerox method of animation popular in the mid 20th century. I probably should have done this instead because the process of inking by hand was a pain in the ass, which I'll get to later, BUT I was also paranoid that if I had transfer film I'd mess up and damage the family printer lol. If you can buy transfer film, look up and see if your printer is compatible with it! Maybe I'll start using it someday. But for those of you who can't get transfer film or don't have a compatible printer, you'll have to ink by hand, anyway.

As you may have noticed, I didn't fill the image across the entire acetate sheet. That's because animators only needed to fill up however much space was required for the scene, and they could leave some of the edges rough if the camera wasn't gonna be picking them up during the photography stage. Here's a real cel from Doomed Megalopolis which illustrates this:

I don't know what the original size for my reference was, but I wasn't looking to do a 1 to 1 recreation. If the original was actually a little bigger, oh well, at least I didn't have to put on as much paint. I knew going in that one of my last steps was gonna be putting a frame around the edges to hide them.

Inking

The acetate paper I've been using is Dura-Lar, specifically the kind that's supposed to be able to take permanent inks. I tested all the inks I had, and most of them either slipped off the sheet completely or didn't show up at all.

The only ones that kinda worked were the Uni Vision fineliner, the Uni Pin fineliners, and the Daler Rowney drawing ink, but even then, I had to be careful with those, they're very easy to smear until they dry.

I did also try out a Sharpie, and it DID seem to stick onto the sheet the best (boy I guess the Dura-Lar paper wasn't lying when it said it was best for permanent inks), but unfortunately, a black Sharpie will appear as blue on acetate, which I didn't want. Maybe in the future I'll look for another kind of permanent marker which actually shows up as black on acetate and comes with very fine nibs sizes.

For this cel, I stuck with the Uni Pin fineliner in the .003 size. Make sure that you wear latex gloves while inking, or at least some kind of thin gloves. You probably will get fingerprints on it, and you will certainly attract dust if you're working on it for long enough, but you can wipe that off the acetate with Windex or something, just be careful not to lift off the lines. If you make a mistake while applying the ink, use rubbing alcohol and a Q-tip to wipe it off.

The fineliner being so easy to slip off meant that in order for it to stick better, I often had to make chicken scratch marks for the larger areas, so I frankly find the line quality to have turned out pretty badly. If I don’t get transfer paper for next time, I'll either get non-Sharpie permanent markers or try the Daler Rowney ink with my dip pens to see if they stick to the acetate better. Here is the result:

If you like rough pen marks, then this look will be great for you! But for me, I felt lucky that many of the lines would at least partially be covered up by the black shadows or the dark background.

After you're done inking, let it dry overnight just to be safe. Before moving onto the painting stage, I'd like to go over another oopsie I made that I kicked myself for later, which was me deciding to flip my original image.

Normally in cel animation, one would ink on the front of the sheet, then put the paint on the back of the sheet, which is what I did for my previous attempts at cel painting, but this time, I decided to put the ink on the back as well. My logic was that if I flipped over the sheet to put the paint on, and the ink was placed in the front, it would likely rub off if I moved the sheet around, so I thought the ink would be better protected on the back side.

This was not the case. If I accidentally put paint outside the lines and went in with a damp brush to lift it off, I would very likely lift off the ink too even though it was "dry" and I'd have to reapply it, or I'd move the piece of paper that I had under my hand to protect the sheet too much and the lines would smear, causing me to have to redraw the lines and wait for them to dry all over again 🤡 All that is to reiterate: Ink should probably go on the FRONT of the sheet, paint should probably go on the BACK of the sheet. If you're doing that, there's probably no need for you to flip your reference image unless you're checking for symmetry in the eyes in your transfer stage or something.

Background

This part was pretty easy for me because I picked a simple background. It didn't have to match the original perfectly because the pattern changes a lot within the few seconds the original frame comes from. I used a mix of black, white, and phthalo blue acrylic paint on watercolor paper that was the same size as the cel, repainting some areas after it was dry to increase the contrast.

(A bit of dust got on my paper, I wiped it off later)

Painting

Whether you're doing a replica or something original, I recommend putting together swatches of all the colors in your reference image so you know how many colors you need to mix and what they look like by themselves. Here's mine:

I put the colors against a gray background so I could get a better sense of what the values were. I didn't manage to recreate the colors exactly for the most part, but with these swatches, I got much closer to the originals than I'm sure I would have gotten if I didn't have them.

When mixing larger batches of color, once you're satisfied with the result, put them in an airtight container so the acrylic doesn't dry immediately, as you'll most likely have to spend hours if not days on a cel project waiting for each layer to dry.

Also, if you're mixing a color, make more than you think you'll need. If you run out in the middle and have to re-mix the color all over again, it's very likely you won't be able to recreate it exactly how it was before. If there is so much as the TINIEST difference in hue, it WILL be noticeable. Trust me, I speak from experience 🤮

When applying the paint, start with the smaller details first like highlights, then gradually do bigger areas. Make sure each layer is completely dry before putting on the next one. Here is my coloring process while still in the early stages:

Yet another blunder from me, I should have gotten close-ups of the sheet so you could see what the painting process looks like better X_X but this pic should give you an idea of what it takes to paint a DIY cel LOL.

You will have to apply the paint generously in order to make it somewhat opaque on the sheet. Acrylic paint just doesn't work the same as the kind of cel paint they used to use, and I'm sure as hell not making the investment for Chromacolour unless, like, this becomes my job, which is highly unlikely. I saw a video from the animator Richard Williams where he explained that the cel paints were basically emulsion paints, which is the kind you put on walls, and I have seen a couple cel hobbyists confirm this, but I'm not buying cans of paint in a bunch of different colors, that would take up so much space!!! I hear the model paints by Tamiya also works pretty well, but again, I'd rather use what I have, so acrylic paint it is!

You may not be able to make your paint layers completely opaque, and they'll probably be somewhat see-through if you hold the sheet up to a light, but unless you're actually making a cel animation and you're photographing the sheets, I wouldn't be too concerned about that. Just make sure they at least LOOK opaque against a solid background, that there's no clear spots where you don't want them, and that you're within the lines (unless you wanna go outside the lines, you do you).

Since you're having to glob the paint on, it can be hard to tell if you're still staying within the lines, so make sure to frequently flip the sheet over to check (guess who was too lazy to flip the sheet very often and made some mistakes which went unnoticed until too far along the project to fix 🤡). Of course, don't flip the sheet over if your paint is very wet, which it shouldn't be so you can maintain control over it.

Something I did to help me stay within the lines was to place lines of paint right along the ink so I would know where to stop. Also, avoid having areas of different colors touch each other before they dry.

And here’s the cel with the background!

I see my mistakes in the color mixing, and putting too much of the highlight color in the eyes, and making some of the shadow lines wobbly, but if you look at it from a distance it’s not too bad, I guess 🤷♀️

You can stop here if you want to and stick the cel in a folder, but I put mine in a picture frame with the background. I also wanted to put an extra “frame” around the cel edges to make it look clean.

Normally, when real cels are sold, they’re put in what’s called a “mat package”, or “presentation mat package”, or “mat board”, which makes the cel look presentable. I didn’t have any of those, nor did I feel inclined to make one, or take any other steps to preserve it because again, I’m not planning on selling this. So instead, I measured the sides of the image, then transferred the measurements to a piece of canvas paper and cut out a hole in the middle. You can use whatever thicker kind of paper you might have. Here is the final assembly:

I had to trim off a bit of the sides of the cel, background, and canvas paper to make it fit inside the frame, so that’s why the hole isn’t totally in the center. But otherwise I’m pleased with the final result. You might have to wipe dust off the glass before putting it on if there is any (which I once again forgot to do XD)

This didn’t turn out perfect, but I learned a lot and this was the best of these attempts at making a fake animation cel I’ve done so far. Next time I might be more ambitious and go back to doing an OC, or perhaps fanart done in this style.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random Thought Before Bed: My New Hobby/Addiction

My collection of souvenir buttons from Japan Society’s repertory film screenings is coming along nicely! I’m still sad that I missed out on the one from their huge Hiroshi Shimizu retrospective, but c’est la vie.

Anyway, new movie review brewing, look for the post tomorrow afternoon!

#Japan Society#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#film#photography#photograph#personal#random thought before bed#Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis#Doomed Megalopolis#To Sleep So As to Dream#Nobuhiko Obayashi#Hiroshi Shimizu

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I still find it fascinating that a lot of people in the UK didn't grow up with 90s anime. You didn't even need Sky!! ITV's CITV and SMTV Live aired Digimon, Cardcaptor Sakura and Pokémon while Channel 5's Milkshake aired Beyblade.

And I've just done a search and Channel 4 apparently aired 3×3 Eyes, Doomed Megalopolis, The Legend of the Four Kings, Cyber City Oedo 808 and Devilman?? I'm really surprised people didn't grow up with anime as much as the cartoons they watched here but to each their own I guess.

#90s anime#cardcaptor sakura#Pokémon#Digimon#Beyblade#beyblade g revolution#beyblade v force#3×3 Eyes#anime#Doomed Megalopolis#The Legend of the Four Kings#Cyber City Oedo 808#Devilman#citv#smtv live#itv#channel 4#sky kids#sky#childhood shows#childhood#tv shows

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just finished Doomed Megalopolis the anime adaptation of Teito Monogatari and wow just wow. That is probably the best anime I've seen in years not counting my rewatches of NGE and Mirai Nikki. The animation was wonderful, the plot was fascinating and Keiko was a totally badass protagonist so her ending was just wow. Anyway might say some others things when I've thought a little more about it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

THIS WAS THE MOTHERFUCKER I WAS LOOKING FOR

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I watched the Doomed Megalopolis OVAs and damn, I liked them so much. The animation is so good, I would love to watch them on a higher resolution, but alas, its what I could fund with subs.

It was so satisfying when kato got his extra awesome ass beaten in the most unexpected way. I liked keiko so much, she is so gentle and a badass at the same time.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

honestly 2024 was weird for film because my best list is:

anarchy (kneecap)

beauty (the wild robot)

doomed yaoi (sonic the hedgehog 3)

fuck the far right (monkey man)

pov: racism (nickel boys)

journalists and realistic gunshots (civil war)

mean girls: church edition (conclave)

the beauty industry sucks: with blood (the substance)

time to cry (look back)

existential dread: killer soundtrack included (i saw the tv glow)

and then there's the worst ones i watched

brutal depressing watch for no reason (joker: folie a deux)

that really bad megamind film (megamind vs the doom syndicate)

cash-grab (the mouse trap)

nickelodeon wtf (saving bikini bottom: the sandy cheeks movie)

hate. HATE. let me tell you how much- (megalopolis)

#kneecap#wild robot#sonic the hedgehog 3#stobotnik#monkey man#please watch monkey man#nickel boys#civil war (a24)#conclave#seriously watch monkey man#the substance#look back#i saw the tv glow#when i finally have a reakdown it'll be i saw the tv glow's fault#WATCH MONKEY MAN#furiosa was good too#megalopolis#francis ford coppola it's on SIGHT#fucking megalopolis

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Best of 2024: Supporting Actor

My Best of 2024 is a series of annual lists in which I pick the best of the best from 2024, all leading up to my official picks for My Top 10 Films of 2024.

I love a good supporting performance, and while 2024 felt lacking in just about every way, there were still plenty of truly great supporting performances out there. Edward Norton's portrayal of Pete Seeger in A Complete Unknown was filled with such patience and attentiveness that shone a beautifully understanding light on the type of artist Seeger was, and how he and others incubated the folk talents of the time, especially Dylan. Kieran Culkin brought such a magnetism to his character's manic-depression in A Real Pain. The humor and pain in his performance is so incredibly raw, and flows so naturally. His breakdown after the concentration camp tour was an overwhelming moment, and his final moments on screen filled me such a shockingly understated sadness. Denzel Washington is having an absolute blast in Gladiator II, and steals not only every scene he was in, but the film in general. Bill Skarsgård's Count Orlok is a figure filled with such impending doom throughout Nosferatu. Stanley Tucci takes the politics of faith and breathes an urgency into his progressive character's plight. Alien: Romulus & Anora's David Jonsson & Yura Borisov are unknown entities that continuously hold their own/steal scenes from their powerhouse leads. And the final three all deliver fantastically lived-in performances, with Cage and O'Connor having the time of their lives while hamming it up in films not quite deserving of their dedication and talent, and Hardy playing it pensive, bringing the intensity of his character to life with an assured patience. Just missing the list are the following Honorable Mentions: Mike Faist in Challengers; John Lithgow in Conclave; Austin Butler in Dune: Part Two; Guy Pearce in The Brutalist; Shia LaBeouf in Megalopolis. A bunch of the cast of Jason Reitman's Saturday Night also belong here, but I gave that cast Best Ensemble, so I tried to keep them out of the running for this list.

Anyway, here they are…

My Top 10 Performances by a Supporting Actor in 2024!

1. Edward Norton in A Complete Unknown

2. Kieran Culkin in A Real Pain

3. Denzel Washington in Gladiator II

4. Bill Skarsgård in Nosferatu

5. Stanley Tucci in Conclave

6. David Jonsson in Alien: Romulus

7. Yura Borisov in Anora

8. Josh O'Connor in Challengers

9. Tom Hardy in The Bikeriders

10. Nicolas Cage in Longlegs

Enjoy!

-Timothy Patrick Boyer.

Next Up: Directing; Lead Actress

More of My Best of 2024…

#mybestof2024#best of 2024#my best of 2024#movies#a complete unknown#a real pain#gladiator II#nosferatu#lists#conclave#alien: romulus#anora#challengers#the bikeriders#longlegs#movie#film#cinema#best supporting actor

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Any recommendations/advice for someone whom wants to get into the Sakura Wars series? Taking into account said person already is a big fan of mecha, (and the Super Robot Wars games) BUT has barely any experience with visual novels.😅

Sakura Wars 1 & 2 have been both translated so those are the most natural place to start. The game is one half visual novel as it's also a tactics game, so the jump wouldn't be too stark if your friend has played the Super Robot Wars games.

If you prefer another medium, Sakura Wars TV series and the first OVA are good places to start, as it introduces all of the characters & core concepts, and the TV series is a retelling of the basic story of the first game, while the OVA serves as a prequel to the games.

The TV show does have a different style from the games, since its directed by the same director as Kino's Journey and Serial Experiments Lain, so is informed by their sensibilities, as well as having the art direction from the same person as Doomed Megalopolis (appropriately enough), but I quite enjoy what it's doing and you might too if you enjoy any of those media too.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed - Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis

Above all else, Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis is a triumph of production design. From the intricately detailed miniature models and matte paintings to the elaborate costumes and soundstages to the charming Harryhausen-inspired stop-motion creature effects, every cent of the enormous budget is clearly evident. Hell, even the lighting—the radiant shimmer of sunlight reflecting off the surface of turbulent water, the eerie pale glow of the full moon peering through a blanket of dry ice clouds, the ominous neon glare of supernatural power—is absolutely immaculate.

The film’s spectacular imagery perfectly matches its themes, which revolve around the conflict between tradition and modernization. At the dawn of the twentieth century, Japan’s cultural leaders have become increasingly obsessed with urban redevelopment as a means of competing on the world stage. Rich industrialists, for example, propose the erection of towering skyscrapers that rival the gods in stature—ostentatious symbols of material wealth (as well as hubris, considering the country’s frequent earthquakes). Nationalistic, xenophobic militarists, on the other hand, argue for “practicality” over hollow aesthetics—borders, walls, and fortifications have far more strategic value than gaudy architecture. Scientists, meanwhile, prefer technological advancement to politics and commerce, embracing the logistical challenges of constructing a vast subterranean railway system. Those attuned to spiritual matters—monks, mediums, practitioners of geomancy—urge these various parties to exercise caution and moderation in their pursuit of the “future,” warning that such unrestrained expansion risks irrevocably tarnishing the sanctity of the land, thus provoking the wrath of ancestral ghosts and guardian deities. “Progress,” after all, can be a destructive force; occasionally, building something new requires burning down the old. These concerns, however, are dismissed as invalid and irrelevant—as obsolete as magic and mysticism in the era of automobiles, engineering, and electricity.

Despite this compelling premise, the plot is rather jumbled, disjointed, and unfocused. Among the sprawling (and bloated) ensemble cast, no single character ever really emerges as a true “protagonist”; vaguely sketched archetypes are introduced rapidly and vanish just as abruptly, only to reappear at seemingly random intervals. In terms of personality and motivation, they’re nearly indistinguishable; consequently, the audience has little opportunity to form a proper relationship with them. Basically, they’re merely props, existing for the sole purpose of communicating exposition and propelling the story from one set piece to the next—they’re functional, but not terribly memorable.

Fortunately, the central villain alleviates this flaw to a significant degree. With his dark, sunken eyes and sharp, almost skeletal facial features, Yasunori Kato is instantly iconic—the epitome of “screen presence.” He exudes menace, personifies malice; every deliciously diabolical line of dialogue that he delivers in his deep, gravelly growl is pure poetry, sending chills of terror down the viewer’s spine. Any scene that excludes him suffers for the omission—though even when he’s absent, his implicit threat still lingers, haunting the frame like a lurking specter, a whispered promise of calamity and impending doom.

Ultimately, director Akio Jissoji’s competent craftsmanship compensates for the movie’s minor formal and structural shortcomings; some mild narrative incoherence notwithstanding, Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis rarely fails to entertain. At the very least, it deserves credit for sheer ambition; precious few blockbusters nowadays dare to be this defiantly audacious and unconventional. Indeed, its superficial blemishes simply make its stylistic virtues more obvious and admirable. Warts and all, it is an essential genre masterpiece, worthy of being ranked alongside such horror classics as The Exorcist, Phantasm, and A Nightmare on Elm Street.

#Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis#Doomed Megalopolis#Doomed: The Last Megalopolis#Teito Monogatari#Yasunori Kato#Japan Society#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#Akio Jissoji#Kyusaku Shimada#film#writing#movie review

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagged by @asamis-jodhpurs

And I'm going to tag @elendsessor and @hyliagirl42

Last song: NEET GAME by Hanabie. I just need someone to scream in my ears for a few minutes while I get the maladaptive daydreaming on

Last book: A Time To Kill by John Grisham. I've decided I love lawyer dramas now it's my Phoenix Wright obsession come back to bite me in real time

Last Movie: Got bit by a sci-fi bug and I finally got around to watching Terminator from 1984. Next on the list is Blade Runner.

Last game: Final Fantasy XIV has been my go-to for awhile, but I did play Lies of P again to prepare for the upcoming DLC.

Last show: Doomed Megalopolis from 1991 because I like anime from that Era and holy crap, that's a crazy one

Sweet/spicy/savory: Spicy all the way ^_^

Relationship: I'm unsure if this is asking what my favorite relationship is or what my status is so I'll just say I'm a sapphic enby with a lot of comfort ships

Fav color: I guess I like gray? It's comforting.

Last internet search: If my lizard can have tomatoes :)

5 notes

·

View notes