#devid striesow

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#die fälscher#stefan ruzowitzky#2007#studio babelsberg#filmfonds wien#medienboard berlin-brandenburg#orf#zdf#august diehl#devid striesow#sebastian urzendowsky#playing for time#der neunte tag#to be or not to be#remember your name#помни имя своё#material#flyweight#landmann#obst & gemüse oder der kunde ist könig#about photography#buw#26#23#future is now

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

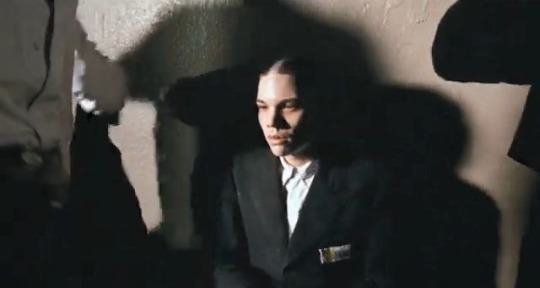

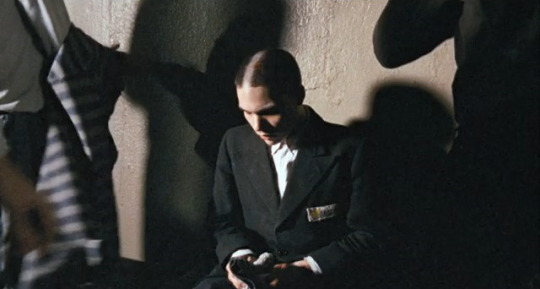

#napola elite für den führer#napola#before the fall#max riemelt#friedrich weimer#heinrich stein#vogler#devid striesow

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

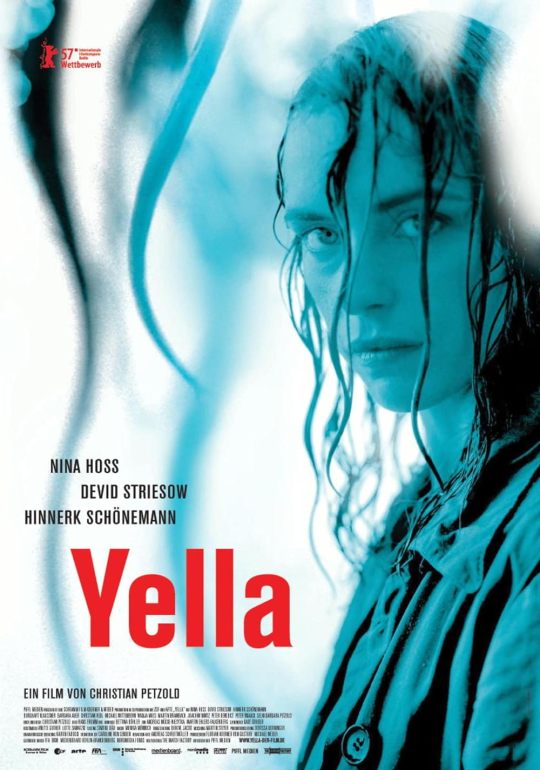

Yella (2007) Christian Petzold

February 17th 2024

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

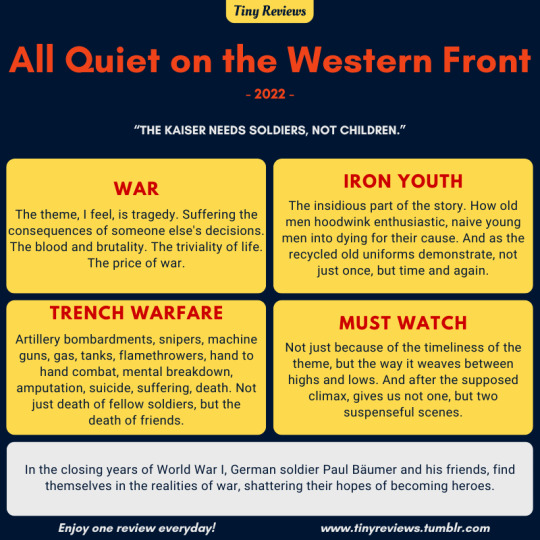

Im Westen Nichts Neues (2022)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just saw a photo of Devid Striesow in real life (like, not as General Friedrichs lmao)

And he looks so much like the image I had of Haie while reading AQOTWF for the first time ?! He’s older ofc, but it’s uncanny

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Das Setting dieses Films birgt so viel Potenzial… Aber na ja 🤷♂️ https://andrepitz.de/2024/09/25/gesehen-napola-2004/

#TomSchilling#NapolaEliteFürDenFührer#napola#MichaelSchenk#MaxRiemelt#JustusVonDohnányi#JoachimBißmeier#FlorianStetter#filmkritik#filme#DevidStriesow#DennisGansel#BeforeTheFall

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Ethical and Existential Underpinnings of "Yella"

In the seascape of cinema, few films manage to intertwine socio-economic critique, existential contemplation, and psychological uncanniness as adeptly as "Yella" (2007) by director Christian Petzold. The film dissects the often disorienting experience of navigating a capitalist world, set against the specific backdrop of East and West German dynamics after reunification. It brings to the forefront a series of foundational beliefs about the nature of capitalism, ethical inconsistencies, existential uncertainty, and the concept of the "unheimlich" or uncanny, each forming a crucial layer of the film's complex narrative texture.

"Yella" explores the inherently ethically compromised nature of capitalism, challenging the notion that it is a morally neutral system. The film operates on both metaphysical and social planes. The protagnist is Yella, played mainly through gesture by Nina Hoss, with minimal dialogue. That the film is named after her makes her the central character, but the film reveals how this is not to be the individualism of other success narratives. Yella leaves her small town Wittenberge, Brandenburg, in former East Germany, for a big job in Hanover (i.e. in the former West.) Her ex-, or estranged (it's never made clear) husband Ben is a failing entrepreneur in Wittenberge who has lost everything in his investment in computer software and hardware (after reunification, East German companies had to invest heavily in Western equipment), but expresses hopes to be the local supplier to an airport he says will be built. All he needs is €25,000 to tide him over.

Ben is stalking Yella, and she is never quite able to shake his presence off. He seems to know exactly where she'll be at any given time. At this point of the film Ben has picks up Yella from her home in a beaten up old Range Rover, in its modern iteration another symbol of capitalist success. Yella has just said goodbye to her father who has offered her a large roll of Euros. When Ben picks her up, he threatens her, then drives himself and Yella off a local bridge. Yella emerges from the water dripping and Ben climbs out exhausted next to her. Converniently her bag appears in the river and she retrieves it, yet strangely for someone who has just been underwater, the clothes in it appear dry. Yella manages to catch the train from this small town in the former East to Hannover to start her new job, and dreams of a new life. The context of post-reunification Germany adds a layer of philosophical and historical depth to the film that is somewhat distinct from a more thematic or aesthetic focus.

When she arrives for work, her hair still damp from the river, which is to say, still carrying the residue of her "Heimat" in the former East, Yella's foray into Western business is quickly revealed as one in a transient world inhabited by outcasts, thieves and cheaters in morally ambiguous scenarios, revealing the ethical pitfalls embedded within capitalist structures. While capitalism often touts itself as a meritocracy where hard work reaps rewards, the film problematises this by showing that not only does one’s success often come with luck and at an ethical cost, but the rules of the game are also inequitably set in advance. The fact that she meets a venture capitalist, Philippe, complicates the narrative of the hustle culture Yella discovers. It's never revealed where Philippe is from. He seems to have no Heimat, no fixed abode. He drives his Audi along empty motorways from motel to motel, from office to office as a ghost, even when the firm he works for fires him. Incidentally, Philippe is played by Devid Striesow, and the actor was born on Rügen in the former East, which makes his relation to the East/West narrative even more ambiguous.

The first character Yella encounters in the West is Philippe, and then Dr. Schmidt-Ott, who hired her for the job she's left her home town for. She discovers Schmidt-Ott in a carpark on her first day. Its revealed that Schmidt-Ott has been banned from the company where Yella is due to start, yet before she discovers this, Schmidt-Ott asks her authoritavely to enter the company offices and bring him something from his desk. When Yella obeys, she is confronted by another employee who reveals that Schmidt-Ott has no authority at all, in fact he's been fired. When Yella eventually hands the money over in a wallet in the back of a taxi, as Schmidt-Ott's company car has been impounded, Schmidt-Ott claims someone's already stolen from it. The obvious implication is it's Yella, though Schmidt-Ott denies this. He then tries to bed her. The fact that she might have stolen from him is irrelevant. Everybody, it seems, is tarnished, and therefore whether one steals or not is of no consequence.

Philippe is also stealing from the companies he negotiates deals with (backhanders). His motive is purely selfish and typically underhand and dubious. He wants to invest in a cheap product that can be bought in every DIY store, but sell it to oil companies for hundreds of thousands. He gives Yella too much money in a series of deposits he asks her to make, seemingly as a test. As it's the €25,000 Ben said he needed, Yella tries to post the excess amount back home to her ex-husband, but Philippe discovers this and catches her out. Again, the handover of a large amount of money happens in a car, and the consequences are irrelevant or ignored as Philippe is also corrupted. The implication again is that everyone is like this. Not to take the money would have been more surprising. Further, Philippe has already revealed that the airport won't be built near Wittenberge as Ben claims, that the contract was lost in a bidding war.

The film’s narrative introduces moral choices that extend beyond individual self-interest. The choices Yella makes are not merely motivated by personal gain; her decision to send money back to Ben, and her promises to repay her father, emphasises the weight of human relationships even within exploitative systems. The existential undercurrents in "Yella" come to the fore here, especially through the themes of anguish and incomplete understanding. In negotiations, the real price of computer equipment is obscured. Decisions made in obscure places, such as the airport, mean life or death. Ben's ultimate act of driving off a bridge serves as a poignant reminder of his existential despair—a drastic response to a world perceived as incomprehensible. Meaning is not given, but something we must navigate or even create amidst uncertainty.

When Yella firsts meets Philippe, she is entranced by the image of rolling waves on his laptop screen. As with the rapid depreciation of computer equipment that Ben originally bought for €80,000, but was forced to sell a year later at huge loss (for €2,000), later revealed to have been bought by one of the Western comanies Yella and Philippe negotiate with, who have reinflated its value back to €80,000, the laptop is a symbol of technology associated with modern capitalism. It's a mirage of freedom and potential, but the waves are contained within the parameters of the screen, emblematic of the systemic confines that capitalism imposes. It potential lures Yella into a script that is not her own but is tempting to follow. The waves, perpetually in motion, encapsulate the fluidity and instability that come with the existential search for meaning. The image suggests a sense of vastness and depth but also instability and unpredictability, mimicking Yella's own journey. She finds herself adrift in a sea of ethical and existential choices, with each wave representing a new challenge, opportunity, or decision. The waves symbolize her enthrallment with the idea of a "better life" that capitalism seems to offer, even as they hint at the unpredictability she will face.

The film deftly deploys the concept of the "uncanny" in its narrative to amplify this existential theme. By injecting the familiar—such as a motel room or office—with a sense of foreboding, "Yella" encapsulates the "unheimlich," where the boundaries between the familiar and unfamiliar blur. The weirdness that enters into Yella's unfamilar new spaces where she thinks she's safe amplifies the sense of discomfort and estrangement. Hospitality inherently contains within it the possibility of hostility. The tension between seeking comfort and encountering the unsettling. Anodyne motel rooms and corridors, nondescript office environments, motorways and car interiors that look alike become spaces of both opportunity and menace.

The idea that Yella is caught in a hermeneutic circle, hallucinated by the spectre of her own tracks, goes beyond just self-deception to suggest how past actions and decisions haunt us. Further, business in the film is portrayed only as gestural tactics, blackmail and deceit, which contests the Western narrative that focuses solely on individual choices in achieving ethical and economic success. This suggests that ethics is deeply interwoven with our interactions with the 'other,' providing a nuanced take on the moral responsibility West Germany has and still has for the former East, and how it fails to take on that responsibility because it's too caught up in the individual hustle.

Another angle is that the partipants in this system wander round as ghosts - literally haunting the banal corridors and generic rented offices. A ghost, a vision of spectre (an apparition) is as menacing as it is promising. Who is the other (the West)? What if the other were worse than anything, a bad messiah, an envoy of the devil, the worst. What if Yella is also the bad messiah, an envoy of the devil, the East German "infecting" the West?

The film distinguishes itself by stressing the textured, situational nature of moral choices and their consequences. It serves as a commentary on the human cost of economic systems, the cultural variables that affect ethical considerations, and the haunting persistence of our actions. In conclusion, "Yella" offers a nuanced exploration of the ethical complexities within capitalist systems. Simultaneously, it engages deeply with existential uncertainties that haunt human life, enriched by its clever use of the "uncanny." Thus, the film emerges as a textured meditation on the intertwining forces that shape our ethical and existential landscapes. Unlike narratives that might end with a cautionary moral lesson, there's a sense of haunting regret to "Yella". A woman left her home behind to follow her dreams, but yearns to return, and keeps falling asleep, before falling dead. Even if one escapes one's immediate situation, consequences follow.

0 notes

Text

Assistir Filme Mademoiselle Paradis Online fácil

Assistir Filme Mademoiselle Paradis Online Fácil é só aqui: https://filmesonlinefacil.com/filme/mademoiselle-paradis/

Mademoiselle Paradis - Filmes Online Fácil

Viena, 1777. Maria Theresia Paradis (Maria-Victoria Dragus) é uma jovem cega extremamente habilidosa no piano. Na esperança de conseguir curar sua cegueira, seus pais a levam até o dr. Mesmer (Devid Striesow), um médico que explora métodos alternativos. Após bastante dedicação, ele descobre que Maria na verdade tem gota e consegue fazer com que ela volte a enxergar. É quando a jovem precisa redescobrir o mundo, já que desde a infância apenas ouvia os sons do que estava ao redor de si.

0 notes

Text

All Quiet on the Western Front (2022)

Director - Edward Berger, Cinematography - James Friend

"What is a soldier without war?"

#scenesandscreens#all quiet on the western front#Im Westen nichts Neues#edward berger#james friend#felix kammerer#albrecht schuch#aaron hilmer#moritz klaus#adrian grünewald#edin hasanovic#daniel brühl#Thibault de Montalembert#devid striesow#Andreas Döhler#sebastian hülk

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wann wird es endlich wieder wie es nie war

"Wann wird es endlich wieder wie es nie war" Ein Film von Sonja Heiss mit Devid Striesow, Laura Tonke, Arsseni Bultmann. Seit gestern in den #Kino-s.

Auf dem Gelände der größten psychiatrischen Klinik Schleswig-Holsteins aufzuwachsen ist irgendwie – anders. Für Joachim, den jüngsten Sohn von Direktor Meyerhoff (Devid Striesow), gehören die PatientInnen quasi zur Familie. Sie sind auch viel netter zu ihm als seine beiden älteren Brüder, die ihn in rasende Wutanfälle treiben. Seine Mutter (Laura Tonke) sehnt sich Aquarelle malend nach…

View On WordPress

#Arsseni Bultmann#Devid Striesow#Film#Joachim Meyerhoff#Kino#Laura Tonke#Sonja Heiss#Wann wird es endlich wieder wie es nie war

131 notes

·

View notes

Photo

All Quiet on the Western Front (2022, Germany)

As a film buff, I retain a preference to reading a book first before seeing its adaptation. But with how many movies I see in a year – sometimes not realizing that a movie is a literary adaptation before starting it – and given how many original source materials are out-of-print or little-read (let alone how slow a reader I am), this is often too difficult a proposition. I make an attempt, however possible, to learn about the themes of an adapted book I was not able to read before heading into a film write-up. Strict fidelity to the text is not a requirement; yet a film adaptation should adhere to the spirit of the text. Any significant changes to that requires the change be done with artistic intelligence and sensitivity. Especially when the adapted book in question is significant in a peoples’ or a nation’s consciousness. Published in 1929, All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque is a landmark novel in anti-war literature and remains – for its depiction of World War I on the bodies and minds of the young men sent to fight it – an important part of modern Germany’s sociopolitical identity.

Lewis Milestone’s 1930 film adaptation at Universal with Lew Ayres was the first cinematic masterpiece following the introduction of synchronized sound and the era of the silent film. Now steps in Edward Berger’s German-language adaptation for Netflix, starring Felix Kammerer, in hopes of reminding viewers that Im Westen nichts Neues (roughly “Nothing New in the West”) is, despite its universal appeal, fundamentally a German story. Berger’s All Quiet is a stupendous technical masterpiece – harrowing visual and sound effects, overflowing with blood and mud. It is among the most technically accomplished war movies this side of Saving Private Ryan (1998). Along the way, Berger’s All Quiet tries for too much, and betrays the characterizations and the intent of Remarque’s novel. With some of its violent scenes shot too aesthetically pleasing alongside an offensive and disrespectful electronic score, 2022’s All Quiet casts the French civilians and soldiers as “the enemy” rather than fellow victims. It veers perilously close to fetishizing the violence within.

Before a brief synopsis, it seems appropriate to reproduce Remarque’s epigraph to All Quiet on the Western Front here:

This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure, for death is not an adventure to those who stand face to face with it. It will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war.

It is 1917, and the Great War has been plodding along for three years. Along with his friends Ludwig Behm (Adrian Grünewald), Albert Kropp (Aaron Hilmer), and Franz Müller (Koritz Klaus), student Paul Bäumer (Kammerer) enlists in the Imperial German Army. They all receive uniforms that, unbeknownst to them, belonged to German soldiers killed in action. Skipping almost entirely over basic training, Paul and his friends deploy to the Western Front, on the French side of the Belgium/France border. There, they befriend Stanislaus “Kat” Katczinsky (Albrecht Schuch) and Tjaden Stackfleet (Edin Hasanovic), who are several years older and have been fighting since close to the war’s beginning. These young men muddle on in drenched trenches, freezing weather, and their comrades’ horrific deaths. Parallel to the plight of Paul and his fellow soldiers is German politician Matthias Erzberger (Daniel Brühl), who secretly travels by train to the Forest of Compiègne to negotiate with French General Ferdinand Foch (Thibault de Montalembert) an armistice.

Also featuring in this film are Devid Striesow as the so-villainous-he-must-be-a-moustache-twirler General Friedrichs, as well as Andreas Döhler and Sebastian Hülk as two German officers.

This All Quiet on the Western Front occasionally frames its violent scenes as too painterly, the combat infrequently choreographed too closely to action movies (e.g., 2017’s Dunkirk is sometimes more of a suspense movie than it is a war movie and Sam Mendes’ 1917 from 2019 is an aesthetic challenge and action movie first, war film second). The opening moments are a dolly shot that linger over a patchwork of corpses strewn about No Man’s Land, with the dull rattle of machine gun fire occasionally disturbing the soil. There is an almost gawking approach to how cinematographer James Friend hovers over the bodies. One character’s death is shrouded in a blinding angelic light – applying too picturesque a technique for a non-fantastical moment. Some exceptions to this voyeuristic, perhaps fetishistic approach to framing warfare appears, including the frightening emergence of French tanks through a cloud of gas. Berger succeeds in displaying war for all its brutality. The film’s sheen, however, comes off as too aggressive and its camerawork reflecting a Netflix-esque polish.

The most glaring misstep from the screenplay by Berger, Ian Stokell, and Lesley Paterson is to include any perspectives not involving Paul and his most immediate comrades. Depicting the insights of Erzberger, Foch, and the fictional General Friedrichs removes one of the central pillars of why All Quiet on the Western Front was such a revolutionary piece of literature. Remarque’s novel, at a time when “anti-war” narrative art was in its infancy, was one of the first war narratives that concentrated entirely on common soldiers – not the officers that commanded them or the politicians that guided them.

Before focusing on Paul and his friends, let us get the officers and politicians out of the way first. The insertion of the armistice negotiations and Gen. Friedrichs’ beliefs over politicians selling the Germany army out – more on this fiction shortly – stunts Paul and his friends’ respective character growths. And despite a decent performance from Brühl, these scenes (except for the final time the elite appear) play out repetitively: Erzberger pleads to Foch for a ceasefire, Foch demands a conditional surrender that will heavily punish Germany, and Erzberger mulls over the terms of surrender. This is all distracting from the common soldiers’ experiences, and provides as much cinematic or educational value as an amateur historical reenactment.

Berger’s stated justification for including these scenes – and letting them drag on too long in the film’s second half – is reasonable. Over the last decade, the actions of far right political groups in Germany have become more visible. These contemporary groups espouse the myths that some in 1920s and ‘30s Germany used to justify the nation’s actions leading up to World War II – all which monolithized and exploited German WWI trauma to serve repugnant purposes. The emotional imbalance of the Erzberger*/Foch scenes paints France and the Allies as an unforgiving “other”, as well as the war’s eventual “victors” (the Allies did prevail in WWI, but Remarque sees no winners in warfare). For a work never meant to be an accusation and written in between the World Wars, the proto-fascist Gen. Friedrichs spits out an early form of the stab-in-the-back conspiracy theory‡. His behavior and appearance, eerily reminiscent of Allied propaganda of Germans as “the Hun”, casts him as the film’s obvious villain. These decisions all provide Berger’s All Quiet with a juxtaposition of morality more appropriate in a WWII movie than one for the Great War.

Beyond the implications of historical morality, Berger, Stokell, and Paterson’s screenplay undermines, at almost every juncture, Remarque’s critiques of the nationalism that began World War I. The decision to have Paul and his friends join the military in 1917 rather than 1914 (as it is in the book) makes it more difficult to have Paul and his friends to have conversations about the nature and the origins of this war. Instead, the screenplay keeps such dialogue to a minimum. As a result, Berger relies on cinematographer James Friend (in his first motion picture of note) to show us close-ups of Paul’s face to reveal his thoughts. In his film debut, Felix Kammerer is doing all he can with his facial and physical acting, but after a certain point this take on Paul results in him being an empty vessel.

Indeed, in Remarque’s book, Paul Bäumer is very much a reactive rather than proactive character. But that does not mean he is without deep introspection, as he is in this 2022 adaptation. Rather than someone who slowly realizes the nationalistic folly of WWI (“We loved our country as much as they; we went courageously into every action; but also we distinguished the false from true, we had suddenly learned to see.”), muses on how wars begin, and is anything but resigned to war’s inevitability, Kammerer’s Paul emotes and says nothing about these aspects of the war. Any critique from nationalism comes not from Paul in this adaptation, but from Gen. Friedrichs’ cartoonishly villainous behavior and Paul’s teachers in the film’s opening minutes. Paul and his friends are no battlefield geniuses, nor are they intellectuals. But the monotony of war – in the absence and presence of violence – grants them knowledge no classroom can give, wisdom that no elder can impart.

Berger, Stokell, and Paterson have the gall to delete entirely arguably the most critical passage in the book: Paul’s return home after being granted time for rest and recreation. After a lengthy spell fighting in the trenches, Paul’s leave completes his development as a naïve and adventure-seeking student to a detached, disillusioned man. Nationalism manipulates his father and others – mostly older men – into believing the justness of the conflict, that serving one’s country in warfare is glorious.

By contrast, Lewis Milestone’s 1930 adaptation takes Paul’s reunion with his teacher a step further than the book. In that version, instead of a chance encounter at a parade ground, Paul visits his teacher during class, with his newest students a rapt audience. The scene that follows is not subtle. But in the context of Milestone’s adaptation, the film earns it. As Paul, Lew Ayres refuses to gift his former teacher the heroic narrative he requests – paraphrasing Horace, decrying nationalism, and simply stating: “We try not to be killed; sometimes we are. That’s all.” One figures these are the words, delivered in sullen fury, by WWI’s veterans. Berger’s adaptation again leans too heavily on Kammerer to relate any semblance of the above ideas. There is no analogue scene to juxtapose the behavioral and psychological differences between battlefront and homefront, no character or even a faraway figure for Paul to verbally challenge. Kammerer’s Paul does undergo a behavioral and cognitive shift by the conclusion of 2022’s All Quiet. Yet, his transformation is not nearly as dramatic as the narrative needs it to be. These failures all stem from a screenplay that might as well have been titled something else. It is damningly incurious about Paul and his friends.

Major movie studio film scores are moving in a particular direction: amelodic, electronic, experimental, metallic, and minimalistic. It seems, by how awards voting bodies and audiences are reacting to such music, what I am about to write paints me more of an outlier than ever.

Composer Volker Bertelmann (also known as his stage name Hauschka; 2016’s Lion) concocts an anachronistic score that includes all these elements. Devoid entirely of recognizable melody (droning strings), Bertelmann’s score has one repetitive three-note idea – I refuse to call this a motif, as it lacks any sense of development from its first to final appearances – that damages and dominates the movie. Inserted in strangely timed moments and meant to intensify dread, Bertelmann’s idea begins from the root note (B♭), up a minor third (D♭), then descends a minor sixth (F). Bertelmann plays these three notes fortissimo, with synthesizer mimicking blaring brass – trust me, you know the sound and you may know its worst practitioners. When recurring underneath the strings, the idea modulates. Memorable as it may be, this metallic sound is more appropriate for hyping young men before a battle or at a rave rather than suggesting dread. Even worse: this is disruptive music. There is a healthy balance to when music should or should not accompany the imagery onscreen. One should notice music in a movie, and it should empower – but not completely overshadow – the emotions and ideas in respect to a certain scene. Bertelmann’s interruptions appear mostly in calms before the proverbial storms. These are the moments the characters and the audience should collect themselves before the killing restarts. Thus, his three-note idea abuses and instantly overstays its welcome.

Is there a place for such colorless, obnoxious, and offensively manipulative music in film? Certainly. Just not in anything entitled All Quiet on the Western Front.

On its surface, a German-language film adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front would restore a cultural and linguistic authenticity to Remarque’s text, one of the most important literary works in German history. To some extent, Berger succeeds. His All Quiet is a technical wonder, but its human interest is nil. Remarque’s prose is not the most accomplished, but his subjective descriptions of trench warfare and his characters’ philosophizing in moments of boredom and quiet were unlike anything almost any Western reader ever encountered. We, the readers, grow alongside Paul and his friends. In 1930, the viewers saw a small group of friends – Milestone’s adaptation is unique in that Paul does not truly emerge as the main character until halfway through the film – see their youth and optimism pummeled away with each shelling and charge. A humanity remains, but tenuously. Berger’s adaptation treads an easier path by inserting a reenactment of the armistice negotiations and expediting Paul’s characterization by immediately dismantling his inwardness and sense of hope.

As a document of a generation’s experiences, a critique of that era’s nationalism that led to the conflict, and a common soldier’s processing of the war’s origin and purpose, this is a poor adaptation of Remarque’s novel. It clears the hurdle in anti-war narratives by decrying warfare as ugly. Beyond this basic expectation, it accomplishes little else.

My rating: 6/10

* Erzberger was assassinated by the far-right terrorist organization Organisation Consul (OC) in 1921. The group was disbanded the year after, but its former members were absorbed into the Nazi Party’s Schutzstaffel (SS).

‡ This conspiracy theory was primarily associated with Jews, but the Nazis also extended it to the political elite that negotiated the surrender. And as if it weren’t obvious enough, one of our German characters is stabbed in the back in the film’s concluding minutes.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#All Quiet on the Western Front#Im Westen nichts Neues#Edward Berger#Felix Kammerer#Albrecht Schuch#Daniel Brühl#Aaron Hilmer#Moritz Klaus#Adrian Grünewald#Edin Hasanovic#Thibault de Montalembert#Devid Striesow#James Friend#Sven Budelmann#Volker Bertelmann#Hauschka#Lesley Paterson#Ian Stokell#Netflix#My Movie Odyssey

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was seriously waiting for someone to do this... Had to do this myself lol

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What a timely movie! Given the current Russian invasion of Ukraine. A few times a generation, we need a movie like this to remind us of the tragedies of war. I really like the tragic theme. The trivial deaths really hits home the realism. MUST WATCH!

All Quiet on the Western Front is a 2022 German epic anti-war film based on the 1929 novel of the same name by Erich Maria Remarque. Directed by Edward Berger, it stars Daniel Brühl, Albrecht Schuch, Sebastian Hülk, Felix Kammerer, Aaron Hilmer, Edin Hasanovic and Devid Striesow.

#all quiet on the western front#daniel bruhl#albrecht schuch#sebastian hülk#felix kammerer#aaron hilmer#edin hasanovic#devid striesow#germany#ww1#epic#war#anti war#movie review#2022#must watch

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

All Quiet on the Western Front

directed by Edward Berger, 2022

#All Quiet on the Western Front#Im Westen Nichts Neues#Edward Berger#movie mosaics#Felix Kammerer#Albrecht Schuch#Devid Striesow#Daniel Brühl#Moritz Klaus#Aaron Hilmer

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

'All Quiet on the Western Lunch' (JK, It's 'Front,' But I Am Hungry)

'All Quiet on the Western Lunch' (JK, It's 'Front,' But I Am Hungry)

How QUIET is it?! (CREDIT: Reiner Bajo/Netflix) Starring: Felix Kammerrer, Albrecht Schuch, Aaron Hilmer, Moritz Klaus, Adrian Grünewald, Edin Hasanovic, Daniel Brühl, Thibault de Montalembert, Devid Striesow, Andreas Döhler, Sebastian Hülk Director: Edward Berger Running Time: 147 Minutes Rating: R Release Date: October 7, 2022 (Theaters)/October 28, 2022 (Netflix) I finally got around to seeing…

View On WordPress

#Aaron Hilmer#Adrian Grünewald#Albrecht Schuch#All Quiet on the Western Front#All Quiet on the Western Front 2022#Andreas Döhler#Daniel Brühl#Devid Striesow#Edin Hasanovic#Edward Berger#Felix Kammerrer#Moritz Klaus#Sebastian Hülk#Thibault de Montalembert

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

All Quiet on the Western Front (2022, dir. Edward Berger) - review by Rookie-Critic

Showing the atrocities of war is always a tightrope walk. You want to show how brutal it is, you want to show people that this thing, this behemoth that has overtaken the world more times than can ever be counted, is horrid and should be avoided if at all possible, but you don't want to desensitize, you don't want to present it so fast, so hard, so unprofoundly nihilistic that it loses its meaning. You don't want to numb people to the pain or push your messaging past its limit, to make the term "war is hell" into a parody of itself. While there were a lot of things I really liked about Netflix and Edward Berger's remake of All Quiet on the Western Front, I feel like this is its biggest issue.

It revels in its "more is more" approach to showing how horrible the Western front lines of the first World War were and it causes the immersion to break and it cheapens the film's very real and very potent anti-war sentiment. The anti-war film is nothing new, we've seen this song dance a million times before, made extremely evident by the fact that this is a remake of the world's first significant anti-war film by the same name, which came out in 1930, 94 years prior to its successor. We've had close to a century of powerful, magnetic, devastating anti-war stories: from Chaplin's The Great Dictator to Kubrick's Paths of Glory AND Full Metal Jacket AND Dr. Strangelove to The Deer Hunter to Apocalypse Now to Das Boot, Platoon, Grave of the Fireflies, 1917, Jojo Rabbit, and on, and on, and on. We get the song, we get the dance, it is a very important message, but we no longer need it spoon-fed to us. The unfortunate thing about the new Western Front is that its images and iconography are intensely powerful and very profound, they get there and they do it fabulously, but then they don't stop. Every scene has an element to it that feels superfluous, that feels like they're bashing your head against the wall that says "war is hell" and screaming at you "DON'T YOU GET IT?!" The answer is, yes, I do, I got it, and I would have without a lot of the, for lack of a better term, extra that's here.

To lay out my point with an example from the film, and don't worry it's not really going to spoil anything (although if you really don't want to know then you should just skip ahead to the next paragraph), but there's a scene in the film involving the general who is in charge of our protagonist's regiment. This immediately follows what is possibly the most intense and brutal sequence in the entire film (which, again, outside of a handful of superfluous elements, is really quite a powerful sequence), and the film juxtaposes all the horror we just witnessed with this general, sitting safely in a very large dining room, eating a feast with a direct subordinate. We get extreme closes ups of everything on the table: olives, fresh bread, a whole leg of lamb, wine, which he drinks a few sips of then tosses the rest on the floor and asks for more. He does this thing with the wine several times throughout the scene. He asks his subordinate about his life back home and what he will return to once the war is over and the subordinate tells him about his family's riding saddle manufacturing/selling business. The subordinate asks the same question to the general and the general goes on a tangent about how he is a soldier who was born in the wrong time because, before this current war, his whole life had been peaceful. He says "what is a soldier without war?" Then tosses what looks like more than half of the meat on his plate to the dog sitting on the floor. This scene would be so infuriatingly impactful and meaningful if the film didn't insist on shoving the message down our throats. I didn't need close ups of the food, I didn't need the spectacle of watching him deliberately waste food and drink, I didn't need this man's hypocrisy slammed into my eyeballs a thousand times over. The atrocious nature of the scenario lies in the scenario itself! Just cut to this horrible man eating his clearly excessive meal in safe quarters after we just watched a lot of men that he is responsible for get brutally mowed down for nothing; no close-ups of the food, no excessive food waste, just the scene itself. Let him talk about how much of a soldier he is. Let this moment be peaceful, that in and of itself would be powerful enough. We, the audience, will get there. We will understand what the film is getting at, it's not that difficult to comprehend, but this is the kind of thing that permeates the entire film.

Here's the thing, I'm still going to give All Quiet on the Western Front a good score, because the truth is I still really liked it. The film has an excellent core. The acting, for the most part, is amazing. The cinematography is unbelievable and the production value is off the charts. Even the story itself, while not really new, is engaging and has a very strong foundation. I just wish it had trusted its audience more and didn't feel the need to just keep adding to itself, to keep piling on more and more until it's just hard to stay engaged. I'm sure this will win a fair amount of Oscars, and it's not entirely undeserving of them, but I don't think it entirely deserves the near-unanimous praise its been getting, because there are a fair amount of problems with it.

Score: 7/10

Currently streaming on Netflix.

#All Quiet on the Western Front#All Quiet on the Western Front 2022#Edward Berger#Felix Kammerer#Albrecht Schuch#Aaron Hilmer#Moritz Klaus#Adrian Grünewald#Edin Hasanovic#Daniel Brühl#Thibault de Montalembert#Devid Striesow#Andreas Döhler#Sebastian Hülk#film review#movie review#2022 films

4 notes

·

View notes