#d’alembert’s dream

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Madame Putiphar Readalong. Book Two, Chapter XXV:

Just like Merteuil and Valmont conspiring against the couple of innocents they want to seduce, Pompadour and Villepastour meet up to discuss Patrick’s (and by extension Deborah’s) fates

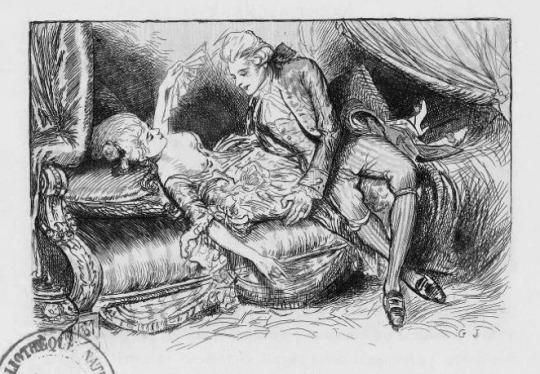

L. Cateret's 1915 Illustration for Les liaisons dangereuses

Pompadour summons Villepastour to “reprimand” him. He declares to be more than happy to receive her sweet punishment. But Pompadour has to immediately cool him off, stressing that, hard to believe as he finds it, she is not into him. (Villepastour is excellent at pr since she thinks she is the exception to confirm the rule)(Pompom is emphatic. She stresses that if it depended on her exclusively, the marques would die in complete abstinence)(she teases since she recieves him -like she does Patrick- during her petit-lever, and while aristocrats recieved many people during their levers and it was meaningless, merely a protocolar thing, I get a sense of her toying with him, showing what he can never have) Since she has mentioned Newton as an example of a celibate man, he claims to not be an expert on the matter, deliberately missing the point she was driving to, to complain about how annoying it is that women now think they can read Newton through what he defines as Voltaire's summaries of his works for the benefit of the ladies. Pompadour seems upset. we get the sense that they’re old “friends” and that they usually tease each other like that. They jokingly hurt eachother, but deep inside they’re both bothered by it.

Borel lets us reconstruct via their dialogue that Pompadour has summoned him via a stern letter, warning him about not harming Patrick. Still, he jokingly (or at least Pompadour ignores him as if it were a joke) asks her for a lettre de cachet. Pomps asks about Patrick, praising him at every opportunity. Villepastour turns her praise into insults (alla Beausteant and Rastignac talking of Delphine at the Opera in Père Goriot) Pompadour realizes he has something against Patrick: “A woman”, replies Villepastour. More 18th c court witticisms ensue, they both insult the one the other is attracted by. There’s -again, ugh- a good line by Villepastour about chastity…. he says he understands the word little, but even so he still understands it more than the virtue that it’s attributed to it. (The french nobles are still the religious and moralistic skeptics)

“Chaste!… Do you understand that word marquis?” “My faith! not very well; however more than virtue which we assign its meaning to.”

(this and all citations translated by @sainteverge )

And now we hop into a Diderotian philosophical dialogue: (nice shakespearean linguistic nihilism too)

“Marquis, believe me, this virtue is but a word.” “Then, madame, if this word designates a virtue which itself is but a word, my poor reason is starting to lose ground; mercy, it’s too much metaphysics!”

It reminds me -perhaps because I tead it last week-of a moment in the Suite de l’Entretien (the sequel to D’Alembert’s Dream) You all know I love Diderot but this philosophical dialogue/private RPF of his friends comes across as sexist in a very basic way too. maybe he’s being true to who the people depicted were like, I don’t know, but it’s still moderately annoying… He has the woman (mme de l’Epinasse) start a philosophical argument with a man (doctor Bordeu) but as soon as he brings up matters she perceives as pertaining to The Sublime(TM), she claims to be exhausted by the discussion, so the doctor scolds her for tiring so fast of “being a man” and backpedaling to being a woman…. (Diderot is ofc not always sexist which is why i enjoy a lot of his work and life choices, etc) -_- Borel, refreshingly has the man instead of the woman reject the philosophical depth of the conversation to drive back to the point of it.

Anyways, Mme P. marks her territory, Patrick is hers (her protégé) and Villepastour must not harm him. But, he explains, he has to expel him, it’s the law, he killed his wife and therefore has no honour-not so much because he has killed a woman, but because he was found guilty of it. That is Villepastour’s chief concern, we suspect-(the man gets yet another cleverly written line):

“Yes, killed; but kind of how we kill in comedies; since she is the one I am dying for.”

There can be no doubts right now that the Marquis is sure Deborah is in fact who she claims to be. (but ofc this doesn’t matter, since Deborah was alive and in fact present during the trial at Tralee, and nobody payed heed to her testimony, that Patrick hadn’t attempted to murder her after robbing her) Even the performance of Honour Villepastour so adores could be served by his helping Patrick get his sentence pardoned. But of course he wants him out of his way. The law like Sade said is not equal for all, it is a tool of the rich to maintain their power (to prevent power from shifting hands like Vautrin said) here we have a pair of aristocrats completely willing to bend the law to to get what they want. Yes, a pair, because even if Pompadour laughs at the idea of musketeer’s honour (completely contradictory concepts according to her) and tells him that if he acts against Patrick Villepastour will answer with his head, she demands for him to break the law to preserve her favourite (we know Patrick is innocent, she knows it and Villepastour knows it. But this is not relevant, she’d still ask the same if he were guilty) who she says, she might deliver to Villepastour in a few days, or manage his destiny herself….

Patrick is in the hands of Fortune, not a Shakespearian Goddess, but a very tanglible, carnal pair of Aristocrats.

#madame putiphar#tumblr do not glitch this post as well please >_>#text post#long post#i(wondering if musketeers were a fad since before dumas)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

It remained for Diderot in his extraordinary D’Alembert’s Dream to propose the crucial trait of nature that transforms mere motion into development and directiveness: the notion of sensibilite, an internal nisus, that is commonly translated as “sensitivity.” This immanent fecundity of “matter” — as distinguished from motion as mere change of place — scored a marked advance over the prevalent mechanism of La Mettrie and, by common acknowledgement, anticipated nineteenth-century theories of evolution and, in my view, recent developments in biology. Yet D’Alembert’s Dream’s very title forewarns readers of Diderot’s candid sense of doubt of his own “likely story,” given the limited scientific knowledge of the time.

Sensibilite implies an active concept of matter that yields increasing complexity, from the atomic level to the brain. Continuity is preserved through this development without any reductionism; indeed, in the scala naturae dynamised by Diderot’s avowed Heraclitean bias for flux, there is a nisus for complexity, an entelechia that emerges from the very nature, structure, and form of potentiality itself, given varying degrees of the organisation of “matter.” From this potentiality and the actualisation of the potentialities of various organisms, sensibilite initiates its journey of self-actualisation and emergent form. Diderot’s holism, in turn, is one of the most conspicuous features of D’Alembert’s Dream. An organism achieves its unity and sense of direction from the contextual wholeness of which it is part, a wholeness that imparts directiveness to the organism and reciprocally receives directiveness from it.

- Murray Bookchin, Toward a Philosophy of Nature: The Bases for an Ecological Ethics

1 note

·

View note

Text

WHAT IS LEFT FOR PHILOSOPHY? A DISAGREEMENT WITH STEPHEN HAWKING

By René Simard

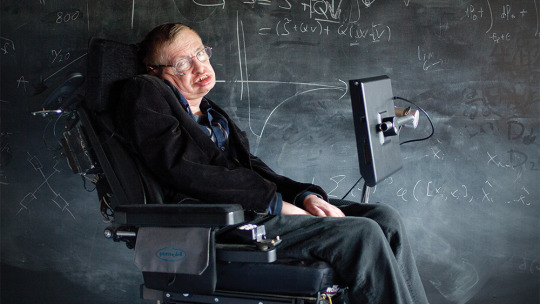

Hawking in action, explaining black holes.(2018) [Redux/Muir Vidler]

Physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking, who died on March 14th, was an inspiration not only because of his spectacular scientific achievements in the face of the neuronal disorder that gradually paralyzed him over the years. He deserves credit for progressive political stands on behalf of the environment and the campaign for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) against Israeli oppression of the Palestinian people. But that needn’t stop us from debating with Hawking over what he had to say about philosophy.

***

In a conference for Google Zeitgeist in 2015, Stephen Hawking repeated what was already found in his book Grand Design, written jointly with Leonard Mlodinow. Here is what he wrote there:

Humans are a curious species. We wonder, we seek answers. Living in this vast world that is by turns kind and cruel, and gazing at the immense heavens above, people have always asked a multitude of questions: How can we understand the world in which we find ourselves? How does the universe behave? What is the nature of reality? Where did all this come from? Did the universe need a creator? Most of us do not spend most of our time worrying about these questions, but almost all of us worry about them some of the time. Traditionally these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead. Philosophy has not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics. Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge. The purpose of this book is to give the answers that are suggested by recent discoveries and theoretical advances.1

If Hawking is right, philosophy cannot respond to such gazing or wondering as has been traditionally considered the beginning of philosophy.2

The reason for such hostility towards philosophy is perhaps the mistake made in expecting that particular discipline to provide us with definitive answers. For, according to Bertrand Russell, “The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty,”3 Then, once definite knowledge on a subject is possible, that subject does not belong to philosophy any more and turns into a science. This has indeed been true about cosmology, and astronomy, for instance. So Hawking faults philosophy because it does not give us a supply of uncontested, demonstrable truths, and this lack of definite answerability is considered to be a characteristic feature of philosophical questions.4

Russell is not alone in this assessment. In Qu’est-ce que la philosophie? (What is Philosophy?), Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari say, “What science is about isn’t concepts, but [mathematical] functions that are given as propositions in discursive systems. The elements of functions are called functors. A scientific notion is not determined by concepts but by functions.”5

Let us reformulate our initial question – What is left for philosophy? – in the framework of the three questions that Immanuel Kant thought his whole philosophy aimed at answering: What can I know? (the question he responds to in the Critique of Pure Reason); What do I have to do? (to which he responds in the Critique of Practical Reason and The Metaphysics of Morals); and, What may I hope? (to which he responds in several works, particularly Religion within the Boundaries of Reason Alone). While scientists such as Hawking can say that philosophy has nothing to say about the first question, the second and third questions, thanks to their nature, might seem to remain for philosophy.

In what follows we can see a response by the philosopher of practice – Marx6, who, unlike Deleuze, does not foresee a future for philosophy if it does not get past itself.

In the Eleventh Thesis in Marx’s “Theses on Feuerbach”, which Marx wrote in 1845, we read, “The philosophers have merely interpreted the world in various ways. The point, however, is to change it”.7

Bees constructing new comb. (n.d.) [Public Domain]

We can see that in saying this Marx is offering a response to at least the second and third of Kant’s three questions. These are matters that remain beyond purely scientific demonstrability. But one may ask if Marx thinks that this changing of the world is on the agenda for the first time in his own epoch. An answer to this can be found in the first volume of Capital, where he writes about what distinguishes us from animals:

A spider conducts operations which resemble those of the weaver, and a bee would put many a human architect to shame by the construction of its honeycomb cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is that the architect builds the cell in his mind before he constructs it in wax. At the end of every labour process, a result emerges which had already been conceived by the worker at the beginning, hence already existed ideally.8

Here Marx acknowledges that even a bee changes its life. In order for an organism to change its physical environment the only necessary condition is its existence.9 This point, recently discussed in the philosophy of biology, was already recognized by Marx. But it is necessary from the very beginning to draw a distinction between biological changing and human changing.

It is possible to go even further and emphasize the point that Marx doesn’t say for whom it is important to change the world. Is the second part of Thesis Eleven the problem of philosophers also? Who, after all, is it that has to change the world? According to the understanding being proposed here, the question for Marx is not whether philosophers should or should not change the world: in a sense, they do that in their daily life. What important is, in a different sense, to replace this world with another one.

Marx’s slogan is therefore not “let’s change the world”, but “let’s change the world by replacing the existing world with the true reality”. The textual support for this reading may be found in Marx’s letter to Arnold Ruge of September1843:

Reason has always existed, but not always in a rational form. Hence the critic can take his cue from every existing form of theoretical and practical consciousness and from this ideal and final goal implicit in the actual forms of existing reality he can deduce a true reality. Now as far as real life is concerned, it is precisely the political state which contains the postulates of reason in all its modern forms, even where it has not been the conscious repository of socialist requirements. But it does not stop there. It consistently assumed that reason has been realized and just as consistently it becomes embroiled at every point in a conflict between its ideal vocation and its actually existing premises.10

By adopting such a standpoint, Marx in a sense follows a tradition known ever since Plato said (in The Republic 509b) that the good is transcendence of what exists, beyond being.

A term in need of explication, used also in the Theses, is the Germam word Praxis (translated as “practice”). Etymologically related to the verb prattein in Greek, it means human action. There is a need to distinguish involuntary from voluntary actions. If what a human does is different from other animals, it is just because it is the action of a human being. At the same time, what Marx wants to propose here is: for humans, in order to exist biologically they have to exist socially. In any case, all humans are already incessantly changing the world. Even more: in fact, every organism, changes its own environment. And, in the same way that there is no organism without there being the environment of that organism, there likewise is not that environment (the way it is) without that organism. Each organism determines its environment and is also determined by it.

A young Karl Marx speaks to his fellow students, flanked by Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Epicurus, in a painting from China's Marx200 Exhibit. (2018) [Public Domain]

From this follows the critique, in Marx’s Third Thesis on Feuerbach, of the materialist doctrine that takes humans to be the passive products of circumstances and education. This doctrine takes the transformation of humans simply as the product of the transformation of circumstances. In so doing it

forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society.

The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice.11

One key word in this passage is “coincidence”, which signifies that by coevolution, mutual transformation of the organisms and the environment, we and our environment co-adapt.11a The world is then in constant change, and we can neither stop this change nor stop playing a role. For the human organism, the change means simultaneous creation and destruction. Whereas in D’Alembert’s Dream Denis Diderot (1713-1784) tells us “everything changes, everything passes away, the only thing that remains is the whole”, for Marx the whole changes as well. We, as long as we exist as organisms, constantly and inevitably export entropy to our environment, and, in so doing, we change our world as well as ourselves.12

This truism is to remind us that philosophers are not exceptions here. Hence, the point stressed here by Marx in this Thesis is nothing but an invitation for a particular change. He thinks that, although humans make their history and change their world, including themselves, they do not do this on the basis of conditions they have chosen, “but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.”13

This is a point established in the philosophy of science. In his article “Extended Phenotypes and Extended Organisms”, Scott Turner, the philosopher of biology writes:

“When organisms can modify environments to beneficial ends, they are liberated from being simply slaves at the mercy of the environment, and become, in a profound sense, its masters.”14

This could also be the slogan of Marx. Philosophy, according to Marx, is a practice engaged in by humans, and like all other practices has some direct or indirect influence on life. What is characteristic of Marx’s era is the following (to quote Ernst Bloch): “Thus the beginning philosophy of revolution, i.e. of changeability for the better, was ultimately revealed on and in the horizon of the future; with the science of the New and power to guide it.”15

If this interpretation is acceptable, Marx intends to introduce an epistemonic approach,16 without employing the term – the term which I want to use to emphasize an approach that retains the unity of intellectual and material life without accepting Hegelian idealism. Once more, like all of us in society, philosophers are certainly changing the world in their daily life. What Marx wants to say is rather that the world’s philosophers, along with all others, should orient their philosophy towards this particular change; a change that is on the one hand conscious and on the other hand enriched by their daily life as philosophers. To give a concrete example, like all other members of the society, the philosophers either participate in elections, or they do not. They make their definite choices in a social milieu and choose one candidate against another, or refuse to vote. Here, as always, even in choosing to be passive, one is in another sense inevitably active.17

In insisting on this type of transformation of the world, Marx remains in the philosophical tradition seen since, for instance, the portrayal of Socrates as depicted in Plato’s dialogue The Crito (47a), where Socrates finds himself obliged to follow the arguments where they lead, and hence offers the prototype of the unity of the practice and theory well known in Marxist thought.

To revitalize this in our era, to orient themselves towards such a change as the response to the second and third questions above, the philosophers have to familiarize themselves with political economy, and scientists have to be acquainted with philosophy, and go beyond their own narrow disciplines.

Detail of Rodin's La porte de l'enfer (The Gates of Hell) at The National Museum of Western Art (2011) (2011) [Creative Commons]

Conclusion:

I would like to finish this article with a reference to a scene from the famous movie, Zorba the Greek, made in 1964 and based on a book with the same title by Nikos Kazantzakis, the progressive Greek writer.

First, a few words on what goes on in the film. Basil, a young British writer, returns to Crete to manage a mine left to him by his father. He meets Zorba, an exuberant Greek who insists on serving as his guide and assistant. The two are different on all counts: Zorba loves to drink, laugh loud, sing, and dance; he follows his own unique lifestyle. Basil, on the other hand, is too polite, timid, and reserved, obsessed by his reading. Nonetheless, they make friends, and collaborate in developing the mine. Zorba agrees to construct a cable-car to develop the mine. Basil trusts him; the project fails in the end.

The particular scene related to the discussion here is the following. Seeing his inability to save a widow killed by the villagers for having sexual relations with the Englishman (Basil) instead of marrying one of the men in the village, Zorba asks Basil:

Why do people die? Why? Tell me!

Basil says: I don’t know.

Zorba: What is the use of all this crap that you read, if they do not respond to such questions? What do those books tell you?

Basil: They tell me about the torture of the ones who cannot respond to such questions.

Zorba: I don’t like torture.

We as philosophers have to contribute in responding to the questions of the Zorbas of our time, including ourselves. Their questions are more horrendous. Here is an example: Why is it that, according to UNICEF, “every 3.6 seconds one person dies of starvation. Usually it is a child under the age of 5.”?18

A philosophical approach aiming at questions of this type does not leave philosophers calm, as Russell suggests, or leave philosophy as a discipline with its own particular function in contrast to science, as Deleuze suggests. Contrary to what is suggested by Deleuze, the aim of this philosophy is still truth, and not just getting a sense of things, as he says.

Nonetheless, in proceeding as philosophers, as Deleuze does suggest, we will be able to “write for the illiterate” where the word “for” in this sentence will not mean “intended for”, or “instead of”, but before, that is, in front of.19 Like Russell, we can be engaged in our life philosophically with the questions posed by our time. Personally, this engagement led to Russell’s loss of his academic position and six months of imprisonment. Deleuze famously says that in philosophy we formulate the problems of our era and create new concepts in response to those problems. In doing so, we can have “a constitutive relationship between philosophy and non-philosophy.”20 Without confronting the intertwined problems of our era, our philosophy remains abstruse and isolated from social life; that is the death of philosophy.

1 Hawking, Stephen; Mlodinow, Leonard, The Grand Design (New York 2010), p. 10.

2 Plato, The Theaetetus, 155 d.

3 Russell, Bertrand, Problems of Philosophy (New York 1997) p. 156

4 Russell, p. 155

5 «La science n’a pas pour objets des concepts, mais des fonctions qui se présentent comme des propositions dans des systèmes discursifs. Les éléments des fonctions s’appellent des fonctifs. Une notion scientifique est déterminée non pas des concepts, mais par fonctions.» Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix, Qu’est-ce que la philosophie? (Paris 2005), p. 117.

6 The greatest thinker of the second millennium according to the BBC (BBC October 1, 1999) (After Marx come Einstein, Newton, Darwin, Aquinas, Hawking – the greatest scientist ever according to Nature, November 6, 2013).

7 Karl, Marx, Theses on Feuerbach, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Volume 5 (Moscow 1976), p. 5.

8 Marx, Karl (1976) Capital I, Ben Fowkes translator (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England 1976), p. 284.

9 Pearce, Trevor (2011) “Ecosystem engineering, experiment, and evolution”, Biol Philos, Volume 26 (2011) 793–812, p. 800

10 Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, Paris 1844, Marx Engels Collected Works, Volume 3 (Moscow 1975), p. 143.

11 Karl, Marx (1845), Theses on Feuerbach, in Marx Engels Collected Works, Volume 5, p. 4.

11 a Here, I use the modified version of what is proposed by Richard C. Lewontin in “The Organism as Subject and Object of Evolution”, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ftzoa2dw3CQ

12 Pearce, Trevor “Ecosystem engineering, experiment, and evolution”, Biol.Philos, Vol. 26 (2011): 793-812, p. 799.

13 Karl, Marx (1851) The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, in Marx Engels Collected Works, Volume 11, (Moscow 1979), p. 103.

14 Turner, Scott (2004) Biology and Philosophy, Volume 19 (2004): 327–352, pp. 328-329.

14 Turner, Scott (2004) Biology and Philosophy, Volume 19 (2004): 327–352, pp. 328-329.

15 Bloch, Ernst, The Principle of Hope, translated by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice and Paul Knight, Volume 1

(Cambridge, Massachusetts 1976), p. 283.

16 I think this can also be seen in the conception of truth as introduced by Marx in the Second Thesis: reality [Wirklichkeit] is introduced as a characteristic of truth besides this sided-ness [Disseitigkeit] and along with power [Macht]. Marx, Karl, Theses on Feuerbach, Marx Engels Collected Works, Volume 5, p. 3.

17 Thus we underline the reverse of the slogan Hegel wrongly attributes to Spinoza, “Omnis determinatio est negatio”. (“Every determination – any definite way that something is – is a negation [of alternatives]”.)

18 https://www.unicef.org/mdg/poverty.html

19 “Écrire pour les analphabètes”, Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix, Qu’est-ce que la philosophie? (Paris 2005), p. 111.

20 “Un rapport constitutif de la philosophie avec la non-philosophie”, Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix, Qu’est-ce que la philosophie? (Paris 2005), p. 111.

The location of René Simard's philosophical inquiries is Montreal.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Text

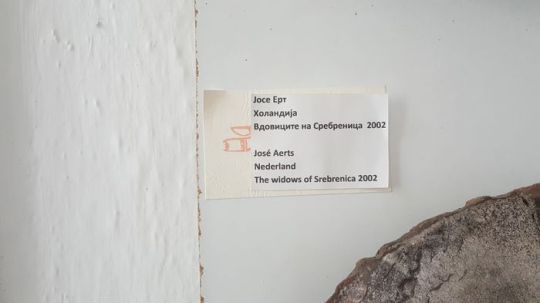

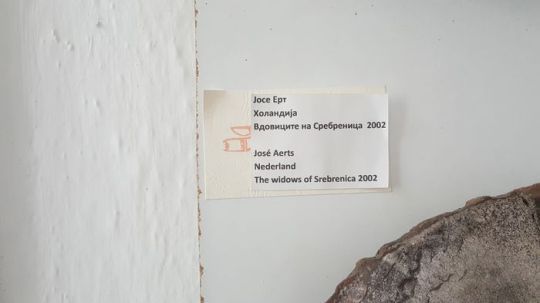

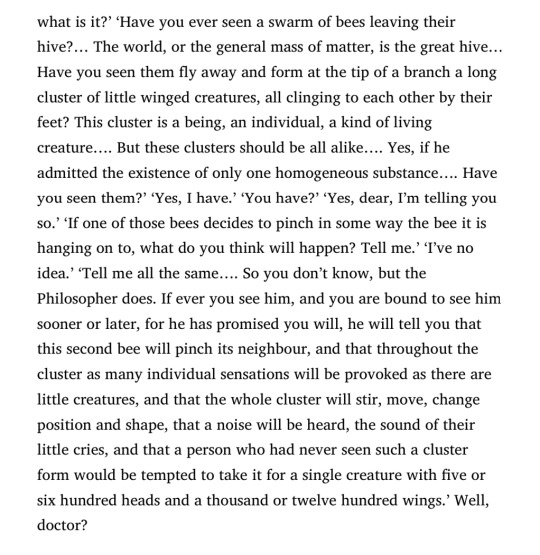

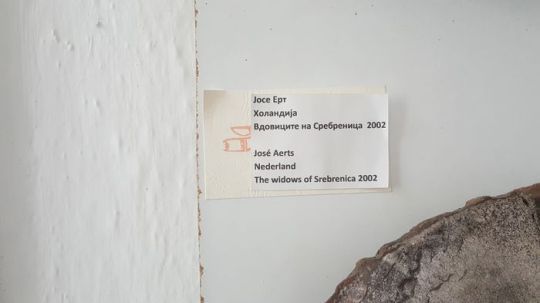

Diderot, D’Alembert’s Dream (1769)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes