#curse this German Peasant's War

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

I love this so much.

#the needle has landed#reader i laughed#panic! it's the mongols#curse this German Peasant's War#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Cinematic bloodlines (1)

The novel "Dracula" gave birth to many, MANY different adaptations, with several of them forming a very particular chain of works that I will call "bloodlines". And the first one actually begins with... a theater play.

In June of 1924, twelve years after the death of Bram Stoker, Dracula was adapted to the stage in Derby, by Hamilton Deane. This play was a huge success - in June of 1927 it was moved to London, and there made so much noise that by September of the same year it crossed the Atlantic and became a Broadway fame. It is from this specific play that the iconic "Dracula outfit" comes from, this evening wear, these soirée clothes with a black cape. It is also at Broadway that one particular actor would start playing Dracula, forever changing the fate of the character: the Hungarian-descendng Bela "Lugosi" Blasko, destined to become the first "face" of Dracula.

We move on to the core of this bloodline: the 1931 "Dracula" movie by Tod Browning. The first "actual" Dracula adaptation on screen, or at least the first talking movie about Dracula, and the one that immortalized Belga Lugosi in the role of the vampire count.

This movie was a huge and lasting success, and erected Dracula as a cultural icon in the American landscape. Jean Marigny wrote that one of the reasons this Dracula worked so well at the time was due to the historical context - the mix of the Great Depression's miserable effects and the inherent xenophobia of the USA, which found themselves "embodied" somehow by Dracula, this sickly and cruel "foreigner", this diseased and malevolent "other" which brought evil into the world. From 1931 to the end of World War II, roughly, American cheap literature and pulp fiction saw a boom of Dracula copies and imitations, so many vampires with Germanic or Slavic names that all were more-or-less subtle personifications of the political threats the USA had to deal with - Bolshevism or Nazism.

Though, again by Marigny's word, this "xenophobic" and "political" reading of Dracula does echo wonderfully one of the elements that made the original novel a success - as beyong a "good versus evil" and "vice versus virtue" battle, the Dracula novel also presented the vampire as a threat coming from a far-away country on the backwards, peasant, superstitious and ancient Eastern depths of Europe, coming into the harmonious and civilized order of Britain to cause trouble and disrupt peace... Perfect to please the inherent xenophobia of Victorian England. Though, it also should be pointed out that the novel, while adhering seemingly to this inherent bias, still was quite subversive - for example by having the Count be clearly more powerful and more prepared than the protagonists, who are all somehow weak or mediocre embodiments of the Victorian society, outmatched and unarmed for quite a long time against this clearly far superior being that is the vampire...

Also, this movie solidified the idea of a younger Dracula - as unlike in the novel, Lugosi's vampire doesn't start as an old man with a long white mustache...

The 1931 Dracula led to the development of what we know today as the "Universal Horror", a series of horror movies developed by Universal Pictures and which formed the first big "cinematic family" of the horror world. In this setting, "Dracula" got a sequel: "Dracula's Daughter" in 1936, very very loosely inspired by both "Dracula's Guest" and "Carmilla" (the two most prominent depictons of a female vampire at the time). The movie is about, as you can guess, Dracula's daughter who is trying to use all the methods she can, both supernatural and scientific, to break the vampirism curse she inherite from her father... The movie is also well-known for playing with the lesbian subtext of Carmilla, reusing it on screen in a Dracula context.

The third part of the unofficial trilogy came in 1943: "Son of Dracula". This is not actually about the literal son of Dracula, unlike "Dracula's Daughter". Rather it is about count Dracula moving not into London but into New-Orleans to spread his vampirism (was it the first time Dracula was depicted arriving in America? I think it might be...). In fact the other working titles for this movies were "The Modern Dracula" and "The Return of Dracula", all much more faithful to what the movie is actually about. This picture is also notorious for being the first time the "Alucard" trick was used in vampire fiction (note that Dracula is not played here by Bela Lugosi, but rather by the other giant of horror Lon Chaney Junior)

After this initial trilogy forming a very loose story (continuity was not the main concern of Universal movie-makers), the Universal Horror entered the era any big franchise enters at one point - crossover times! With "House of Frankenstein" in 1944, and "House of Dracula" in 1945, both about events gathering under one same roof Dracula, the creature of Frankenstein and the Wolf Man, the three iconics of the Universal Horror.

Then we entered the era of parodies, and the Universal Dracula ended up with the 1948 parody "Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein".

This is the end for the old "classic" Universal line. There is actually more down it, Universal didn't stop its vampire movies there, but I'll keep it for another post, because I want to conclue this post with three other movies.

Bela Lugosi is quite famously THE Dracula - and many believe that he was the only actor for Dracula in the Universal movies. Yet, as said above, he wasn't present in all of them - Son of Dracula, for example, was without him. Rather, this idea comes from the fact that, after playing Dracula on stage and on screen, Lugosi ended trapped in the role and type-casted as a vampire. He notoriously played in an unofficial trio of vampire movies which solidifed his reputation as "the vampire actor".

The first was another Tod Browning production made not so long after the original Dracula: 1935's Mark of the Vampire (or Vampires of Prague), which was strongly inspired by a silent horror movie currently lost, "London after Midnight". There, Lugosi played a "count Mora" who causes mysterious deaths in Prague with his daughter Irena. (And in this angle you could consider this movie a sort of unofficial rival to Universal's "Dracula's Daughter").

Followed in 1943 "The Return of the Vampire" by Lew Landers, which was basically trying to be an unofficial, unlicensed sequel to the Universal 1931's Dracula, even having Lugosi play the main vampire haunting London (Armand Tesla). This picture also contains a copy of Universal's Wolf Man in the person of Andréas the werewolf.

The last one is another parody in the line of the Abbott and Costello movie (in fact it was heavily inspired by it): the 1953 John Gilling's movie "Mother Riley Meets the Vampire", where the vampire is titled Van Houssen and plans to dominate the world by... building a robot army. Well... it was the 50s.

All of these lead to the treatment of Lugosi' vampire typecasting as both his legacy and his curse - to the point that when he was buried, he demanded it was in his Dracula costume...

#vampire#vampire movies#vampire cinema#vampire media#dracula#cinematic bloodlines#dracula adaptations

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

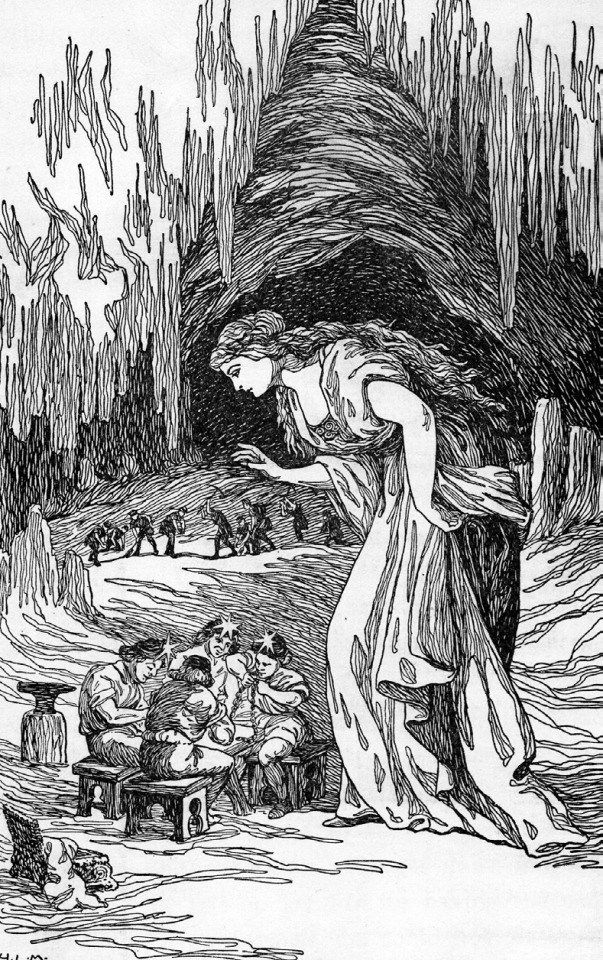

Sleeping Beauty Spring: "Dornröschen" ("Briar Rose")/"Sleeping Beauty" (1955 German film)

This West German film is one of many cinematic fairy tales to come out of Germany in the 1950s and the early '60s, and one of several to be dubbed into English by Childhood Productions as fodder for Saturday "kiddie matinees" in America. Having already seen two of that company's other dubbed releases, Fritz Genschow's Cinderella and Erich Kobler's Snow White, I looked forward to seeing this Sleeping Beauty, knowing that like the other two, it would probably be fairly corny, but still charming. I was right.

Like the same year's West German Cinderella, this Sleeping Beauty was directed by Fritz Genschow, who also co-wrote the script with Renée Stobrawa. Both Genschow and Stobrawa appear onscreen too, as the King and the castle housekeeper Miss Hustlebustle. (Just as they both appeared in Cinderella as the heroine's father and the Fairy Godmother.) The cast also features Angela von Leitner as Princess Briar Rose and Gert Reinholm as Prince Charming.

In the opening scene, with her husband away on business of state, the lonely Queen wanders the castle grounds longing for a child, until she discovers a mysterious tower in a remote spot. Unbeknownst to her, this is the home of the Wicked Fairy, who gives the Queen a potion that will let her conceive child, on the condition that she invite the Fairy to the christening as a godmother. In truth, the child born from that potion will be evil and ugly. But a magical statue of a frog comes to life and prevents the Queen from drinking it, urging her instead to bathe in a lake enchanted by twelve good fairies. The result, of course, is the birth of a lovely little princess, and the twelve good fairies are invited to the christening. The good fairies are beauties in white robes, each with a headdress of enormous flowers on her head; by contrast, the Wicked Fairy wears black robes and a headdress decked with dead plants. The death curse she places on the princess is softened to sleep by the Rose Fairy.

Sixteen years later, the castle celebrates Briar Rose's birthday. Extensive comic relief is provided by a bevy of mischievous little kitchen boys, whom the cook, Mr. Puddingbowl, struggles to keep in line, while also pursuing a December/December romance with the housekeeper Miss Hustlebustle. Meanwhile, the Wicked Fairy disguises herself as an old woman and approaches Briar Rose, inviting her to come to her tower for a special birthday present. Briar Rose declines at first because her party guests are arriving. But at the ball she finds herself courted by a buffoonish suitor, Prince Suchabore, the son of King Bubble and Queen Babble. To get away from him, she sneaks off to the tower, where of course the "old woman" is waiting with a spindle.

As the Wicked Fairy spreads her curse through the castle grounds, the court doesn't physically fall asleep; instead they all freeze in place like statues, with some of them posed in comical positions for the next hundred years. (Mr. Puddingbowl about to box a kitchen boy's ear, another boy swinging on a string of onions, one man just about to sneeze, etc.) The twelve good fairies then surround the castle with a protective hedge of rosebushes. Many princes over the years try to fight their way through the thorns – we see a montage of them in their assorted colorful, exotic costumes – only to die and transform into red roses on the hedge.

At long last, however, Prince Charming arrives, and he learns the story of Briar Rose from a group of peasant children singing a folksong about her. (One based on the real German children's song "Dornröschen war ein schönes Kind," sometimes known in English as "There Was a Princess Long Ago.") Then from an old man, he gains a flute to summon the twelve good fairies. When he makes his way through the briars and is led by the magic frog to the tower, the Wicked Fairy conjures up a herd of hideous monsters to stop him. But the Prince's sword and the twelve good fairies' magic defeats them and the Wicked Fairy disappears. Prince Charming wakes Briar Rose with a kiss, the royal court unfreezes with no idea that a hundred years went by, and all live happily ever after.

As I expected, this is a slightly clunky Sleeping Beauty. But it's an endearing one all the same, filmed in lush green settings, with pretty 18th century-inspired costumes, and with enjoyable creative touches that don't detract from its basic faithfulness to the Grimms' tale.

I do wish I could see the original German version of the film and not just the English dubbed version, though. Like Childhood Productions' other dubs of German fairy tale films, this dub adds excessive voiceover narration by Paul Tripp, as well as fairly charming yet forgettable songs by Milton and Anne Delugg.

An essential Sleeping Beauty this isn't, but it's still an enjoyable sample of 1950s German fairy tale cinema.

@ariel-seagull-wings, @reds-revenge, @thealmightyemprex, @paexgo-rosa, @thatscarletflycatcher, @faintingheroine, @the-blue-fairie, @themousefromfantasyland, @autistic-prince-cinderella

#sleeping beauty spring#dornröschen#sleeping beauty#fairy tale#live action film#1955#fritz genschow#germany

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m reading Markus Wolf’s memoirs and I absolutely love his description of growing up in Moscow but also that rapid shift in tone omfg

We adjusted slowly to a strange language and culture, fearful of the harsh manners of the children who shared our courtyard. “Nemets, perets, kolbassa, kislaya kapusta,” they would shout after us: “Germans—pepper, sausage, sauerkraut.” They laughed at our short trousers, too, and we begged our mother for long ones. Finally she gave in with a sigh, saying, “You’re proper little men now.”

But we were soon fascinated by our new environment. After our provincial German childhood, the bustling city, with its rough and ready ways, thrilled us. In those days people still spat the husks of their sunflower seeds onto the pavement, and horse-drawn traps clattered through the street. Moscow was still a “big village,” a city with peasant ways. At first we attended the German Karl Liebknecht School (a school for children of German-speaking parents, named after the Socialist leader of the January 1919 Spartacist uprising, who was murdered in Berlin shortly thereafter), then later, a Russian high school. By the time we became teenagers we were barely distinguishable from our native schoolmates, for we spoke their colloquial Russian with Moscow accents. We had two special friends in George and Victor Fischer, sons of the American journalist Louis Fischer. It was they who gave me the nickname “Mischa,” which has stuck ever since. My brother Koni, anxious not to be left out, took the Russian diminutive “Kolya.”

The Moscow of the thirties remains in my memory as an era of light and shadow. The city changed before our eyes. By now I was a rather serious teenage boy and no longer thought of Stalin as a magician. But as the new multistory apartment blocks soon appeared around the Kremlin, and the amount of traffic suddenly increased as black sedans replaced the pony traps, it was as if someone had waved a powerful wand and turned the Moscow of the past into a futuristic landscape. The elegant metro, with its Art Deco lamps and giddyingly steep escalators, hummed into life, and we would spend the afternoons after school exploring its vaults, which echoed like a vast underground church. The disastrous food shortage of the twenties abated, but despite the new buildings, my family’s friends, mainly Russian intellectuals, lived cheek by jowl in tiny apartments. There were spectacular May Day parades. The exciting news of the day carried highlights of the age like the daring recovery of the Chelyushkin expedition from the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean after its conquest of the North Pole. We followed these events with the enthusiasm that Western children devoted to their favorite football or baseball teams.

With similar passion Koni and I both joined the Soviet Young Pioneers— the Communist equivalent o f the Boy Scouts—and learned battle songs about the class struggle and the Motherland. As Young Pioneers we marched in the great November display on Red Square commemorating the Soviet revolution, shouting slogans of praise for the tiny figure in an overcoat on the balustrade above Lenin’s tomb. We spent our weekends in the countryside around Moscow, gathering berries and mushrooms because even as a city dweller our father was determined to preserve his nature worship as a way of life. I still missed German delicacies, though, and found the sparse Soviet diet, with its mainstays of buckwheat porridge and sour yogurt, desperately boring. Since then I have learned to love Russian food in all its variety, and if must say so, I make the best Pelmeni dumplings (stuffed with forcemeat) this side of Siberia. But I have never developed a great fondness for buckwheat porridge, probably as a result of having consumed tons of the stuff in my teens.

In summer I was dispatched to Pioneer camp and elevated to the role of leader. I wrote to my father complaining about the miserable gruel and military discipline that prevailed there. Back came a typically optimistic letter, bidding me to resist the regime by forming a commission with my fellow children. “Tell them that Comrade Stalin and the Party do not condone such waste. Quality is what counts.. . . Under no circumstances must you, as a good Pioneer and especially as a Pioneer leader, quarrel! You and the other group leaders should speak collectively with the administration. . . Don’t be despondent, my boy.”

The Soviet Union was now our only home, and on my sixteenth birthday, in 1939, I received my first Soviet papers. Father wrote to me from Paris, “Now you are a real citizen of the Soviet people,” which made me glow with pride. But as I grew older I realized that my father’s infectious utopianism was not my natural leaning. I was of a more pragmatic temperament. Of course, it was an exhilarating time, but it was also the era of the purges, in which men who had been feted as heroes of the Revolution were wildly accused of crimes and often condemned to death or to imprisonment in the Arctic camps. The net cast by the NKVD—the secret police and precursor of the KGB—closed in on our emigre friends and acquaintances. It was confusing, obscure, and inexplicable to us youngsters, schooled in the tradition of belief in the Soviet Union as the beacon of progress and humanitarianism.

But children are sensitive to silences and evasions, and we were subliminally aware that we were not party to the whole truth about our surroundings. Many of our teachers disappeared during the purges of 1936-38. Our special German school was closed. We children noticed that adults never spoke of people who had “disappeared” in front of their families, and we automatically began to respect this bizarre courtesy ourselves.Not until years later would we face up to the extent and horror of the crimes and Stalin’s personal responsibility for them. Back then, he was a leader, a father figure, his square-jawed, mustached face staring out like that of a visionary from the portrait on our schoolroom wall. The man and his works were beyond reproach, beyond question for us. In 1937, when the murder machine was running at its most terrifyingly efficient, one of our family’s acquaintances, Wilhelm Wloch, who had risked his life working for the Comintern in the underground in Germany and abroad, was arrested. His last words to his wife were “Comrade Stalin knows nothing of this.”

Of course, our parents tried to keep from us their fears about the bloodletting. In their hearts and minds, the Soviet Union remained, through all their doubts and disappointments, “the first socialist country” they had so proudly told us about after their first visit in 1931.

My father, I now know, was fearful for his own life. Although his wife and children had been granted Soviet citizenship because we lived there, he spent much of his time abroad and so was not a citizen. He was, however, still able to travel on his German passport, even though his citizenship had been revoked. He had already applied for permission from the Soviet authorities to leave Moscow for Spain, where he wanted to serve as a doctor in the International Brigades fighting against General Franco’s Fascists in the bitter Civil War there. Spain was the arena where the Nazi military tried out its deadly potential, practicing for its later aggression against other vulnerable powers. Throughout Europe, left-wing volunteers were flooding to the aid of the Republicans against the Spanish military insurgents. For many in the Soviet Union, fighting there also meant a ticket out of the Soviet Union and away from the oppressive atmosphere of the purges. Decades later, a reliable friend of the family told me that my father had said of his attempts to reach Spain: “I’m not going to wait around here until they arrest me.” That revelation wounded me, even as a grown man, for it made me realize how many worries and reservations had been hidden from us children by our parents in the thirties, and how much sorrow must have been quietly harvested around us among many of our friends in Moscow.

My father never did reach Spain. For a year, his application for an exit visa lay unanswered. More and more of our friends and acquaintances in the German community had disappeared and my parents could no longer hide their anguish. When the doorbell rang unexpectedly one night, my usually calm father leapt to his feet and let out a violent curse. When it emerged that the visitor was only a neighbor intent on borrowing something, he regained his savoir-faire, but his hands trembled for a good half hour.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q. You’ve written for Culture Matters on a number of topics. Can you start by saying something about Marx, Engels and Lenin’s comments on religion?

Roland Boer: ‘Opium of the people’ is where we should begin. For a young Marx in his twenties it meant not simply a drug that dulls the senses and helps one forget the miseries of the present. Instead, the metaphor of opium in the nineteenth century was a complex one. On the one hand, opium was seen as a cheap and widely available medicine, readily accessible for the poor. Marx himself used opium whenever he felt ill, which was often. On the other hand, opium became increasingly to be seen as a curse. Medical authorities began to warn of addiction and that perhaps its healing properties were not what many people believed. And the scandal of the British Empire forcing opium on the Chinese in order to empty Chinese coffers became more and more apparent. In short, opium was a very ambivalent metaphor: blessing and curse, medicine and dangerous drug, British wealth and colonial oppression. This ambivalence carries through to religion.

As for this ambivalence, Engels is our best (early) guide. Despite giving up his Reformed faith – with much struggle – for communism, he kept a lifelong interest in religion. He would frequently denounce religion as a reactionary curse, longing for it to be relegated to the museum of antiquities. But he also began to see a revolutionary potential in religion, which came to its first full expression in his 1850 piece on the German Peasant War. This was a study of Thomas Müntzer and the Peasant Revolt of 1525, which was inspired by a radical interpretation of the Bible.

It was the first Marxist study of what later came to be called (by Karl Kautsky) Christian communism, although Engels tended to see the theological language as a ‘cloak’ or ‘husk’ for more central economic and political matters. But Engels was not yet done. Not long before his death in 1895, an article appeared on early Christianity. Here Engels challenged everyone – Marxists and Christians alike – to take seriously the argument that early Christianity was revolutionary. Why? It drew its members from slaves, peasants and unemployed urban poor; it shared many features with the communist movement of his own day; it eventually conquered the Roman Empire. We may want to question the last assertion, as indeed later Marxists like Karl Kautsky did, for Christianity – unexpectedly for some – became a religion of empire rather than conquering it.

Does Lenin have any insights for understanding religion? Generally, he was more trenchantly opposed, not least because the Russian Orthodox Church sided so clearly with the collapsing tsarist autocracy. Yet there are some insights. Apart from Lenin’s continued interest in sectarian Christian groups after the October revolution, let me make two observations.

The first is that Lenin agreed with a position that had been hammered out in the German Social-Democratic Party: religious belief is not a barrier to joining a communist party. Marx and Engels had already indicated as much in terms of the First International. Why? Religion is not the primary problem; instead, the main target is economic and social exploitation. Indeed, this principle has by and large been followed by nearly all communist parties since then (although the Communist Part of China is an interesting exception).

Second, Lenin reinterpreted Marx’s ‘opium of the people’ not as ‘opium for the people’ (as is commonly believed) but as a kind of ‘spiritual booze’. This term has many layers in Russian culture, all the way from Russian Orthodox theology to the complex role of vodka in Russian society. The main point is that ‘spiritual booze’ is not immediately a dismissal, but rather a grudging acknowledgement of the sheer complexity of religion itself.

— Marx, Engels, and Lenin on Religion, from an interview with Roland Boer

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

German III: 5.11-5.15

Vocabulary:

erschrecken

get scared

der Schnurriemen

cord, lace

der Atem

breath

wirken

take effect

eigen

own (adj.)

sich fürchten vor

be afraid of

der Sarg

coffin

ehren

to honor

der Diener

servant

der Strauch

shrub

schüttern

to shake

der Fluch

curse

die Angst

fear

eisern

made of iron

die Pantoffel

slipper

bereit stellen

set out

Snow White (Schneewittchen):

Die stolze Königin sprach vor ihrem Spiegel: "Spieglein, Spieglein an der Wand, wer ist die Schönste im ganzen Land?" Da antwortete der Spiegel: "Frau Königin, Ihr seid die Schönste hier, aber Schneewittchen über den Bergen, bei den sieben Zwergen ist noch tausendmal schöner als Ihr." Da erschrak° die Königin und plante, wie sie Schneewittchen töten könnte. Sie kleidete sich wie eine alte Frau und ging über die sieben Berge zu den sieben Zwergen, klopfte an die Tür und rief: "Schöne Ware, gute Ware." Schneewittchen guckte zum Fenster hinaus und fragte: "Guten Tag, liebe Frau, was habt ihr zu verkaufen?" — "Schöne Schnurriemen° in allen Farben." "Der guten Frau kann ich vertrauen," dachte Schneewittchen und es öffnete die Tür und kaufte einen schönen Schnurriemen. "Kind," sprach die Alte, "wie du aussiehst! Komm, ich will dich ordentlich schnüren." Aber die Alte schnürte so schnell und so fest, dass dem Schneewittchen der Atem° verging, und es für tot hinfiel. "Nun bist du die Schönste gewesen," sprach die Stiefmutter und ging schnell weg. Als die sieben Zwerge nach Hause kamen, erschraken sie, als sie ihr liebes Schneewittchen auf der Erde liegen sahen. Schnell schnitten sie die Schnurriemen entzwei und Schneewittchen begann zu atmen.

The proud queen said in front of her mirror: "Mirror Mirror on the wall, who's the fairest of them all?" Then the mirror replied: "Ms. Queen, you are the most beautiful here, but snow white over the mountains, with the seven dwarfs is a thousand times more beautiful than you. " Then the queen was startled and planned how she could kill Snow White. She dressed like an old woman and went across the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs, knocked on the door and shouted: "Nice goods, good goods." Snow White looked out the window and asked: "Hello, dear lady, what do you have to sell?" - "Nice string in all colors." "I can trust the good woman," thought Snow White and she opened the door and bought a nice string. "Child," said the old woman, "how you look! Come on, I want to lace you up properly." But the old woman laced so fast and so tight that Snow White's breath went out and she fell dead. "Now you were the most beautiful," said the stepmother, and quickly left. When the seven dwarfs came home, they were startled when they saw their lovely Snow Maiden lying on the ground. They quickly cut the strings in half and Snow White began to breathe.

Als die böse Königin nach Hause gekommen war, ging sie vor den Spiegel und fragte:"Spieglein, Spieglein an der Wand, wer ist die Schönste im ganzen Land?"Da antwortete der Spiegel wieder:"Frau Königin, Ihr seid die Schönste hier, aber Schneewittchen über den Bergen, bei den sieben Zwergen ist noch tausendmal schöner als Ihr. "Da erschrak die Königin und machte noch einen Plan, um Schneewittchen zu töten. Sie machte einen giftigen Kamm, verkleidete sich als eine andere alte Frau, ging über die sieben Berge zu den sieben Zwergen und klopfte wieder an die Tür. "Geht nur weiter, ich darf niemand hereinlassen," sprach Schneewittchen. "Aber anschauen darfst du," sagte die Alte und hielt den Kamm in die Höhe. Der Kamm gefiel dem Kind so gut, dass es die Tür öffnete und ihn kaufte. Da sprach die Alte: "Nun will ich dich ordentlich kämmen."Kaum hatte sie den Kamm in die Haare gesteckt, als das Gift darin wirkte° und das Mädchen niederfiel. "Jetzt bist du tot," sprach die böse Königin und ging fort. Zum Glück war es bald Abend und die sieben Zwerge fanden Schneewittchen auf der Erde. Sie fanden den giftigen Kamm und zogen ihn heraus und Schneewittchen kam zu sich. Sie warnten es noch einmal, niemandem die Tür zu öffnen.

When the evil queen came home, she went in front of the mirror and asked: "Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the most beautiful in the whole country?" Then the mirror replied again: "Ms. Queen, you are the most beautiful here, but Snow White over the mountains, with the seven dwarfs is a thousand times more beautiful than you. "Then the Queen was startled and made another plan to kill Snow White. She made a poisonous comb, disguised herself as another old woman, went across the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs, and knocked on the door again. "Go away, I can't let anyone in," said Snow White. "But you can look at it," said the old woman, holding up the comb. The child liked the comb so much that it opened the door and bought it. Then the old woman said: "Now I want to comb you properly." No sooner had she put the comb in her hair when the poison worked in it and the girl fell down. "Now you're dead," said the angry queen, and left. Fortunately, it was soon evening and the seven dwarfs found Snow White on Earth. They found the poisonous comb and pulled it out and Snow White came to. They warned her not to open the door to anyone.

Die Königin stellte sich zu Hause vor den Spiegel und fragte: "Spieglein, Spieglein an der Wand, wer ist die Schönste im ganzen Land?" Da antwortete der Spiegel wie vorher: "Frau Königin, Ihr seid die Schönste hier, aber Schneewittchen über den Bergen, bei den sieben Zwergen ist noch tausendmal schöner als Ihr." Die Königin war wütend und schrie: "Schneewittchen soll sterben, und wenn es mein eigenes° Leben kostet!" Da nahm sie einen Apfel, der sehr schön aussah, und machte eine Hälfte giftig. Dann verkleidete sie sich als alte Bauersfrau, ging über die sieben Berge zu den sieben Zwergen und klopfte wieder an die Tür. Da sprach Schneewittchen: "Ich darf keinen Menschen einlassen; die sieben Zwerge haben mir´s verboten."

The queen stood in front of the mirror at home and asked: "Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the most beautiful in the whole country?" Then the mirror replied as before: "Ms. Queen, you are the most beautiful here, but Snow White over the mountains, the seven dwarfs are a thousand times more beautiful than you." The queen was angry and shouted: "Snow White should die, and if it costs my own ° life!" So she took an apple that looked very nice and made half of it poisonous. Then she disguised herself as an old peasant woman, went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs and knocked on the door again. Then Snow White said: "I must not let anyone in; the seven dwarfs have forbidden it to me."

"Das ist mir auch recht," antwortete die Bauersfrau, "meine Äpfel will ich loswerden. Da schenke ich dir einen." "Nein," sprach Schneewittchen, "ich darf nichts annehmen." — "Fürchtest du dich vor° Gift?" sprach die Alte, "siehst du, ich schneide den Apfel in zwei Teile; ich esse eine Hälfte und du kannst die andere essen." Als Schneewittchen sah, dass die alte Bauersfrau den Apfel aß, nahm es die giftige Hälfte. Aber kaum hatte es ein Bissen im Mund, so fiel es tot zur Erde nieder. Da lachte die Königin und sprach: "diesmal können die Zwerge dich nicht erwecken!" Und als sie zu Hause den Spiegel befragte: "Spieglein, Spieglein an der Wand, önste im ganzen Land?" so antwortete er endlich:"Frau Königin, Ihr seid die Schönste im Land."Da hatte ihr neidisches Herz Ruhe.

"That's fine with me," replied the farmer's wife, "I want to get rid of my apples. I will give you one." "No," said Snow White, "I can't take anything." - "Are you afraid of ° poison?" said the old woman, "you see, I cut the apple in two; I eat one half and you can eat the other." When Snow White saw that the old peasant woman was eating the apple, she took the poisonous half. But as soon as she had a mouthful, she fell dead to the ground. Then the queen laughed and said: "This time the dwarves cannot wake you up!" And when she asked the mirror at home: "Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the most beautiful in the whole country?" he finally answered:" Ms. Queen, you are the most beautiful in the country." Her envious heart was at rest.

Als die Zwerge Schneewittchen fanden, konnten sie es wirklich nicht aufwecken: das liebe Kind war tot und blieb tot. Sie weinten drei Tage lang. Es sah noch so frisch und schön aus, dass sie sprachen: "Das können wir nicht in die schwarze Erde versenken," so machten sie einen Sarg° aus Glas, legten es hinein und schrieben seinen Namen darauf und dass es eine Königstochter wäre. Sie setzten den Sarg auf den Berg und einer von ihnen blieb immer dabei.

When the dwarfs found Snow White, they really couldn't wake her up: the dear child was dead and stayed dead. They cried for three days. She still looked so fresh and beautiful that they said: "We cannot sink her into the black earth," so they made a coffin made of glass, put her in and wrote her name on it and that she was a king's daughter. They put the coffin on the mountain and one of them always stayed with her.

Nun lag Schneewittchen lange, lange Zeit in dem Sarg und sah immer aus, als ob es schliefe. Es geschah aber, dass ein Königssohn in den Wald kam und das Zwergenhaus fand. Er sah den Sarg and das schöne Schneewittchen darin und las, was darauf geschrieben war. Da sprach er zu den Zwergen:"Lasst mir den Sarg haben, ich gebe euch, was ihr dafür haben wollt." Aber die Zwerge antworteten: "Wir geben ihn nicht um alles Gold in der Welt." Da sprach er: "So schenkt ihn mir, denn ich kann nicht leben, ohne Schneewittchen zu sehen; ich will es ehren° wie mein Liebstes" Als er so sprach, gaben ihm die guten Zwerglein den Sarg. Seine Diener° trugen ihn auf den Schultern fort. Aber sie stolperten über einen Strauch°, und von dem Schüttern° fuhr das giftige Apfelstück aus dem Hals. Bald öffnete sich Schneewittchen die Augen und sprach: "Ach, Gott, wo bin ich?" Der Königssohn sagte vor Freude: "Du bist bei mir," und erzählte ihr alles, was geschehen war. Dann sprach er: "Ich habe dich lieber als alles auf der Welt; komm mit mir, du sollst meine Gemahlin werden." Das war dem Schneewittchen recht und man plante die große Hochzeit.

Now Snow White lay in the coffin for a long, long time and always looked as if she was sleeping. But it happened that a king's son came into the forest and found the dwarf house. He saw the coffin and the beautiful Snow Maiden in it and read what was written on it. Then he said to the dwarves: "Let me have the coffin, I'll give you what you want for it." But the dwarves replied, "We don't give it for all the gold in the world." Then he said: "So give it to me, because I cannot live without seeing Snow White; I will honor her as my dearest" When he spoke like this, the good dwarfs gave him the coffin. His servants carried him on the shoulders. But they stumbled across a shrub, and the poisonous apple slid out of her neck from the shaking. Snow White soon opened her eyes and said, "Oh, God, where am I?" The king's son said with joy: "You are with me," and told her everything that had happened. Then he said: "I prefer you to everything in the world; come with me, you shall be my wife." The Snow Maiden was fine and the big wedding was being planned.

Schneewittchens gottlose Stiefmutter wurde auch zu der Hochzeit eingeladen, und als sie sich mit schönen Kleidern angezogen hatte, ging sie vor den Spiegel und sprach: "Spieglein, Spieglein an der Wand, wer ist die Schönste im ganzen Land?"cDer Spiegel antwortete:"Frau Königin, Ihr seid die Schönste hier, aber die junge Königin ist tausendmal schöner als Ihr." Da stieß die böse Stiefmutter einen Fluch° aus und wollte gar nicht auf die Hochzeit kommen; doch sie musste die junge Königin sehen. Als sie da war, erkannte sie Schneewittchen und vor Angst° stand sie da und konnte sich nicht bewegen. Aber es waren ihr schon eiserne° Pantoffeln° über Feuer gestellt, die sie tragen musste und darin so lange tanzen, bis sie tot zur Erde fiel.

Snow White's godless stepmother was also invited to the wedding, and when she had dressed with beautiful clothes, she went in front of the mirror and said: "Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the most beautiful in the whole country?" The mirror replied: "Queen, you are the prettiest here, but the young queen is a thousand times more beautiful than you." Then the evil stepmother uttered a curse and did not want to come to the wedding at all; but she had to see the young queen. When she was there she recognized Snow White and with fear ° she stood there and could not move. But she already had iron slippers over fire that she had to carry and dance in it until she fell dead to the ground.

-chen and -lein:

all words with these endings are neuter words and their plural is the same as their singular

Fun Facts:

Prince Ludwig of Bavaria´s castle Neuschwanstein has become known as the Märchenschloss (Fairy Tale Castle) to tourists traveling to Germany from places all around the world. It is seen here from the Marienbrücke, which can be reached by taking a short hike up into the mountains behind the castle. And if you aren´t out of breath from the hike up, the view will surely take your breath away. It is fabulous! For those of you unable to travel abroad, head to Disneyworld or Disneyland where Neuschwanstein was the model for Cinderella´s castle.

The Brothers Grimm collected an abundance of children´s stories that have been read worldwide for generations. In addition to the Grimms´ fairy tales, there is another well-known book about two mischievous boys named Max und Moritz, which was first published in German in 1865. Below you see the preface, which has been translated into English

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alright, gang, strap in. Here are my thoughts on cursing in the 24th Century / the Universal Translator...

First off, I like to believe that we don’t see cursing in Star Trek (TNG/DS9/VOY) because actually by that point in the future cursing has become superfluous and irrelevant. Cursing was, historically, the language of the peasant. It wasn’t used by the upper class. And when you think about it, that kind of makes sense. Why do we curse? Usually because we’re frustrated about our current situation. And who’s more likely to be frustrated by their current situations: a farmer who doesn’t know how he’s going to feed his wife and children, or the wealthy landlord who owns the shire and all it’s land?

Now that’s not to say that people aren’t without struggle in the 24th Century, but we do know that the narrative is always being told to us through the lens of human protagonists (Picard, Sisko, Janeway, Archer). Earth is supposed to have become a paradise. There’s no more war or money so presumably a lot less need to curse.

Again, that’s not to say there isn’t cursing, but it is to say that when they spent a boatload of time and effort creating artificial intelligence that could interpret and translate all languages, they probably didn’t bother to put in a cuss words subroutine. It just... wasn’t necessary.

“But what about the Klingons?” you say! “We hear them curse all the time! I think I even heard some Romulan curses before on TNG!”

Yeah, okay. Thank you for the audience participation. To that I say: this brings up an interesting point. WHY do we EVER hear ANY ALIEN LANGUAGES when supposedly everybody on the shows are speaking their own native tongues? And if you tell me it’s because the individuals are willingly choosing to not have their words translated, to that I say: Yeah, nah. Because if that were the case eavesdropping would be impossible. Quark would never have anything to worry about because Odo presumably was raised primarily learning Cardassian and Bajoran. He wouldn’t speak Ferengi so Quark would just always speak Ferengi when he was up to no good.

Now, you could of course argue that I’ve picked a poor example, because there’s actually never any indication that Odo has a universal translator. His true form never shows any kind of chip or anything. And we know from that one DS9 episode where Quark & fam (spoilers!!) go back in time to Earth that not only are universal translators on ships and in the main computers of starbases, they’re also implanted in the humanoid brain. Most likely a small procedure performed not long after a child begins learning how to speak. Anyway -- we could argue that either 1.) because Odo is a changeling his ability to morph into other creatures also gives him an innate ability to understand languages extremely quickly, or 2.) that the implant version of the universal translator is relatively new technology by DS9 era and therefore may not have been common place then, and maybe not even around at all in TNG, but living on such a diverse space station most of the DS9 crew got them implanted.

Next point of tension that has always confused me: Why do entire planets only have ONE language when Earth has COUNTLESS? Why is there French and German and English and Spanish but somehow only one Klingon or Romulan or Bajoran dialect? Furthermore, where did all the other languages go? Why do the humans really only speak English?

Here’s my theory on that: There actually ARE many languages on each planet, and even still on Earth. However, all speech on any individual planet is likely fairly similar to each other while also being fairly unique from all other planets just by nature of the natural evolution of linguistics. Now if you really wanna get into the psychology of it, language is actually in part biologically wired into us as humans. We all learn language in about the same ways and at around the same time in our development (withstanding, of course, particular conditions that have late onset of verbal behavior). Yes, it’s entirely valid to argue that since life on other planets would evolve in completely different ways than on Earth, it is entirely possible and in fact most likely that language would be crazy different on any other planet just because the biology of any other form of life would be so drastically different from that on Earth. Now that’s a slippery slope argument right there so I’m just going to stop you. Because Star Trek already solved that one for us with one simple phrase: HUMANOID. Yes, it is entirely ludicrous to think life on another planet would look so incredibly similar to life on Earth, but SOMEHOW, MAGICALLY in this universe and this version of the future, that is the case. (And, like, if you really wanna go crazy, you could blame that on an infinite number of realities whereby some version of our universe would indeed be populated almost exclusively by humanoids, but I digress...)

ANYWAY! So! The point of that last crazy long paragraph was that all language on any planet is RELATIVELY similar, so translators have simply packed them all together to create one, general language for each world. Which means the humans aren’t actually speaking “English,” they are speaking “Earth” or “Human” or whatever... And you can even go one step further and say that we as a viewing audience are, too, being impacted by the universal translators. As the message is being sent through to us, it’s being translated into whatever language we speak.

Now! Where does that leave us on alien cursing? Welp, I’m going to say that in the case of Klingons and to a lesser extend Romulans, their cursing is still kept in tact by the translators because the usage of these words is intrinsically linked to the CULTURE of these worlds. Klingons are these strong, warrior race. To them, cursing each other off is sort of equivalent to humans arm wrestling. It doesn’t really prove anything, no one is hurt in the end, but you did just prove how macho you are to everyone in the room!

But is cursing really important to humans??? I dont know, maybe some of you guys can argue it is. But, to me, when someone curses at me, all it really tells me about them is that...... they’re angry. And honestly there are a hundred other ways to tell a person is angry with you, you don’t really need the curse words for it. The way the person looks, how they are acting, their inflection, how loudly they are speaking, so on and so forth. Plus! I even took a literature & compositions class once where the professor made a really valid point. “Have you ever been cursed out in another language?” she asked us, “Or overheard someone cursing out somebody else? You don’t need to know what the words mean. You can just TELL that they are curse words.” And that’s because curse words are almost ALWAYS (for humans, anyway - and in all languages) FRICATIVES. Fricatives are words that employ very harsh sounds and letter combinations. “f” and “sh” most notably, but also sounds like “k” and “t”. These harsh sounds carry the meaning of the words just by it’s phonics.

Anyway. Why did I say all that? I dont know I kind of got off track by the end there but my main point is that curse words don’t really mean a lot for humans. Our culture wouldn’t be completely demolished without them. If they disappeared from existence tomorrow we could all carry on just fine. But that may not be the case for other planets and cultures. So that’s why there’s still cursing in Klingon and Romulan tongues.

I still don’t have a very good answer for that “Why can we ever hear an alien language?” question. Not one that really satisfies me, anyway. But yeah. Here’s an incredibly long post that likely no one will read and which in truth really adds absolutely nothing to the viewing experience of star trek. But thanks for tuning in. These are the inane ramblings of a psychology undergrad who just really likes asking pointless questions about non-existent future technology and alien interactions.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

NAME: Wladislaus Dragwlya ALIAS: Vlad III, Vlad Țepeș, Vlad Dracula, Lord Impaler/the Impaler Prince, the Little Dragon, Count Dracula, Lancer of Black. AGE: 45 SPECIES: Human, Heroic Spirit (call him a vampire and he’ll end you.)

PERSONAL !

MORALITY: lawful / neutral / chaotic / good / neutral / evil / true RELIGION: Orthodox Christian (former) Catholic (current) SINS: greed / gluttony / sloth / lust / pride / envy / wrath VIRTUES: chastity / charity / diligence / humility / kindness / patience / justice KNOWN LANGUAGES: In life; formerly Romanian/ Old Church Slavonic, Latin, Turkish and perhaps even German. However, due to being summoned as a Heroic Spirit he has knowledge of whatever language is needed during the Holy Grail War(s).

SECRETS: His favourite books are romance novels!

PHYSICAL !

BUILD: scrawny / bony / slender / fit / athletic / curvy / herculean / pudgy / average HEIGHT: 6″2 / 191cm. SCARS / BIRTHMARKS: Has numerous scars, though most tend to appear like tiny slivers on his body. There are too many to count. Most notable are the one’s around his wrists and ankles, where he was chained for a number of years due to his boyars betrayal. ABILITIES / POWERS: Summoned as a Lancer class servant; Vlad III is proficient with the use of his spear and the technique Kazıklı Bey; an anti-army Noble Phantasm that brings forth innumerable stakes to pierce foes from the ground upwards. There is also his secondary ability, the Legend of Dracula, but we won’t speak of that here. RESTRICTIONS: Remembered as a great hero in Wallachia, Vlad’s absurd level of power is only ever truly effective in the country that he has made his name. When forced to fight outside of this land, his parameters as a servant drops from around 10 at his peak, to 6, severely weakening him and his abilities. If forced to use that Noble Phantasm, Vlad’s otherwise tactical approach to battle is reduced to nothing more than that of a blood-starved fiend, making him both an unpredictable mess and an easy target for other, stronger servants to finish him off.

FAVOURITES !

FOOD: Small side- platters that can accompany his favourite alcoholic beverages. DRINK: Red wine. PIZZA TOPPING: Psh, he not peasant enough to reduce his pallet to mere pizza. (Totally a meat-feast kind of guy.) COLOUR: Black, red and the occasional flashes of gold. MUSIC GENRE: Classical, soul and electronic rock. BOOK GENRE: Romance, fantasy, history and detective fiction. MOVIE GENRE: Doesn’t have a preference (yet!) SEASON: Winter. CURSE WORD: “Du-te dracu!” SCENT ( S ): Strong and earthy scents, burning wood, cologne.

FUN STUFF !

SINGS IN THE SHOWER: No. LIKES PUNS: Puns are only acceptable if they aren’t centered around a certain, taboo topic thank you!

Tagged by: @freischultz - asdfjkl thank you! Tagging: @drakulya, @motherconquest, @musicalhistory and anyone else who fancies this!

#[The King speaks.]#[Headcanons of the King.]#//If you've already done this feel free to ignore! I'm super late to the party so I don't know who's been tagged or not o.o"#Kazikili-Voyvoda

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

You do not do, you do not do Any more, black shoe In which I have lived like a foot For thirty years, poor and white, Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.

Daddy, I have had to kill you. You died before I had time— Marble-heavy, a bag full of God, Ghastly statue with one gray toe Big as a Frisco seal And a head in the freakish Atlantic Where it pours bean green over blue In the waters off the beautiful Nauset. I used to pray to recover you. Ach, du. In the German tongue, in the Polish town Scraped flat by the roller Of wars, wars, wars. But the name of the town is common. My Polack friend Says there are a dozen or two. So I never could tell where you Put your foot, your root, I never could talk to you. The tongue stuck in my jaw. It stuck in a barb wire snare. Ich, ich, ich, ich, I could hardly speak. I thought every German was you. And the language obscene An engine, an engine, Chuffing me off like a Jew. A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen. I began to talk like a Jew. I think I may well be a Jew. The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna Are not very pure or true. With my gypsy ancestress and my weird luck And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack I may be a bit of a Jew. I have always been scared of you, With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo. And your neat mustache And your Aryan eye, bright blue. Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You— Not God but a swastika So black no sky could squeak through. Every woman adores a Fascist, The boot in the face, the brute Brute heart of a brute like you. You stand at the blackboard, daddy, In the picture I have of you, A cleft in your chin instead of your foot But no less a devil for that, no not Any less the black man who Bit my pretty red heart in two. I was ten when they buried you. At twenty I tried to die And get back, back, back to you. I thought even the bones would do. But they pulled me out of the sack, And they stuck me together with glue. And then I knew what to do. I made a model of you, A man in black with a Meinkampf look And a love of the rack and the screw. And I said I do, I do. So daddy, I'm finally through. The black telephone's off at the root, The voices just can't worm through. If I've killed one man, I've killed two— The vampire who said he was you And drank my blood for a year, Seven years, if you want to know. Daddy, you can lie back now. There's a stake in your fat black heart And the villagers never liked you. They are dancing and stamping on you. They always knew it was you. Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I'm through. In Memory of W. B. Yeats by W. H. Auden I He disappeared in the dead of winter: The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted, And snow disfigured the public statues; The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day. What instruments we have agree The day of his death was a dark cold day. Far from his illness The wolves ran on through the evergreen forests, The peasant river was untempted by the fashionable quays; By mourning tongues The death of the poet was kept from his poems. But for him it was his last afternoon as himself, An afternoon of nurses and rumours; The provinces of his body revolted, The squares of his mind were empty, Silence invaded the suburbs, The current of his feeling failed; he became his admirers. Now he is scattered among a hundred cities And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections, To find his happiness in another kind of wood And be punished under a foreign code of conscience. The words of a dead man Are modified in the guts of the living. But in the importance and noise of to-morrow When the brokers are roaring like beasts on the floor of the Bourse, And the poor have the sufferings to which they are fairly accustomed, And each in the cell of himself is almost convinced of his freedom, A few thousand will think of this day As one thinks of a day when one did something slightly unusual. What instruments we have agree The day of his death was a dark cold day. II You were silly like us; your gift survived it all: The parish of rich women, physical decay, Yourself. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry. Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still, For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives In the valley of its making where executives Would never want to tamper, flows on south From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs, Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives, A way of happening, a mouth. III Earth, receive an honoured guest: William Yeats is laid to rest. Let the Irish vessel lie Emptied of its poetry. In the nightmare of the dark All the dogs of Europe bark, And the living nations wait, Each sequestered in its hate; Intellectual disgrace Stares from every human face, And the seas of pity lie Locked and frozen in each eye. Follow, poet, follow right To the bottom of the night, With your unconstraining voice Still persuade us to rejoice; With the farming of a verse Make a vineyard of the curse, Sing of human unsuccess In a rapture of distress; In the deserts of the heart Let the healing fountain start, In the prison of his days Teach the free man how to praise. Proem: To Brooklyn Bridge by Hart Crane How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest The seagull's wings shall dip and pivot him, Shedding white rings of tumult, building high Over the chained bay waters Liberty— Then, with inviolate curve, forsake our eyes As apparitional as sails that cross Some page of figures to be filed away; —Till elevators drop us from our day ... I think of cinemas, panoramic sleights With multitudes bent toward some flashing scene Never disclosed, but hastened to again, Foretold to other eyes on the same screen; And Thee, across the harbor, silver-paced As though the sun took step of thee, yet left Some motion ever unspent in thy stride,— Implicitly thy freedom staying thee! Out of some subway scuttle, cell or loft A bedlamite speeds to thy parapets, Tilting there momently, shrill shirt ballooning, A jest falls from the speechless caravan. Down Wall, from girder into street noon leaks, A rip-tooth of the sky's acetylene; All afternoon the cloud-flown derricks turn ... Thy cables breathe the North Atlantic still. And obscure as that heaven of the Jews, Thy guerdon ... Accolade thou dost bestow Of anonymity time cannot raise: Vibrant reprieve and pardon thou dost show. O harp and altar, of the fury fused, (How could mere toil align thy choiring strings!) Terrific threshold of the prophet's pledge, Prayer of pariah, and the lover's cry,— Again the traffic lights that skim thy swift Unfractioned idiom, immaculate sigh of stars, Beading thy path���condense eternity: And we have seen night lifted in thine arms. Under thy shadow by the piers I waited; Only in darkness is thy shadow clear. The City's fiery parcels all undone, Already snow submerges an iron year ... O Sleepless as the river under thee, Vaulting the sea, the prairies' dreaming sod, Unto us lowliest sometime sweep, descend And of the curveship lend a myth to God. Tom O' Bedlam's Song anonymous ballad, circa 1620 From the hag and hungry goblin That into rags would rend ye, The spirit that stands by the naked man In the Book of Moons, defend ye. That of your five sound senses You never be forsaken, Nor wander from your selves with Tom Abroad to beg your bacon, While I do sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. Of thirty bare years have I Twice twenty been enragèd, And of forty been three times fifteen In durance soundly cagèd. On the lordly lofts of Bedlam With stubble soft and dainty, Brave bracelets strong, sweet whips, ding-dong, With wholesome hunger plenty, And now I sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. With a thought I took for Maudlin, And a cruse of cockle pottage, With a thing thus tall, sky bless you all, I befell into this dotage. I slept not since the Conquest, Till then I never wakèd, Till the roguish boy of love where I lay Me found and stript me nakèd. While I do sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. When I short have shorn my sow's face And swigged my horny barrel, In an oaken inn, I pound my skin As a suit of gilt apparel; The moon's my constant mistress, And the lovely owl my marrow; The flaming drake and the night crow make Me music to my sorrow. While I do sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. The palsy plagues my pulses When I prig your pigs or pullen Your culvers take, or matchless make Your Chanticleer or Sullen. When I want provant, with Humphry I sup, and when benighted, I repose in Paul's with waking souls, Yet never am affrighted. But I do sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. I know more than Apollo, For oft when he lies sleeping I see the stars at mortal wars In the wounded welkin weeping. The moon embrace her shepherd, And the Queen of Love her warrior, While the first doth horn the star of morn, And the next the heavenly Farrier. While I do sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. The Gypsies, Snap and Pedro, Are none of Tom's comradoes, The punk I scorn, and the cutpurse sworn And the roaring boy's bravadoes. The meek, the white, the gentle, Me handle not nor spare not; But those that cross Tom Rynosseross Do what the panther dare not. Although I sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. With an host of furious fancies, Whereof I am commander, With a burning spear and a horse of air To the wilderness I wander. By a knight of ghosts and shadows I summoned am to tourney Ten leagues beyond the wide world's end: Methinks it is no journey. Yet I will sing, Any food, any feeding, Feeding, drink or clothing; Come dame or maid, be not afraid, Poor Tom will injure nothing. After the Persian by Louise Bogan I I do not wish to know The depths of your terrible jungle: From what nest your leopard leaps Or what sterile lianas are at once your serpents' disguise and home. I am the dweller on the temperate threshold, The strip of corn and vine, Where all is translucence (the light!) Liquidity, and the sound of water. Here the days pass under shade And the nights have the waxing and the waning moon. Here the moths take flight at evening; Here at morning the dove whistles and the pigeons coo. Here, as night comes on, the fireflies wink and snap Close to the cool ground, Shining in a profusion Celestial or marine. Here it is never wholly dark but always wholly green, And the day stains with what seems to be more than the sun What may be more than my flesh. II I have wept with the spring storm; Burned with the brutal summer. Now, hearing the wind and the twanging bow-strings, I know what winter brings. The hunt sweeps out upon the plain And the garden darkens. They will bring the trophies home To bleed and perish Beside the trellis and the lattices, Beside the fountain, still flinging diamond water, Beside the pool (Which is eight-sided, like my heart). III All has been translated into treasure: Weightless as amber, Translucent as the currant on the branch, Dark as the rose's thorn. Where is the shimmer of evil? This is the shell's iridescence And the wild bird's wing. IV Ignorant, I took up my burden in the wilderness. Wise with great wisdom, I shall lay it down upon flowers. V Goodbye, goodbye! There was so much to love, I could not love it all; I could not love it enough. Some things I overlooked, and some I could not find. Let the crystal clasp them When you drink your wine, in autumn. Elegy Written in a Country Church-Yard by Thomas Gray The curfew tolls the knell of parting day, The lowing herd winds slowly o'er the lea, The ploughman homeward plods his weary way, And leaves the world to darkness and to me. Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight, And all the air a solemn stillness holds, Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight, And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds: Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tower The moping owl does to the moon complain Of such as, wandering near her secret bower, Molest her ancient solitary reign. Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade, Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap, Each in his narrow cell for ever laid, The rude Forefathers of the hamlet sleep. The breezy call of incense-breathing morn, The swallow twittering from the straw-built shed, The cock's shrill clarion, or the echoing horn, No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed. For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn, Or busy housewife ply her evening care: No children run to lisp their sire's return, Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share, Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield, Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke; How jocund did they drive their team afield! How bow'd the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

1 note

·

View note

Text

The TV Show Trials - Lore

Lore is a horror anthology television series developed by the creator of the podcast of the same name, Aaron Mahnke. The show combines documentary footage and cinematic scenes to tell horror stories and their origins.

After two months in a row of reviewing serial TV shows, I decided to take a break and watch another anthology series. For some reason, I was originally under the impression that this was going to be a fiction series (mostly because I hadn’t researched it before I watched it) but I was pleasantly surprised by the documentary-cinematic hybrid. Before I review each episode individually, I will mention that the entire series is only twelve episodes so I was unable to review my regular fifteen episodes.

They Made a Tonic

Before we knew how disease spread, medicine was as much superstition as it was science. And in the small New England towns of the 1800s, there is a belief that consumption can only be stopped by making sure the dead are actually dead.

This episode was the perfect introduction to this series and I was incredibly surprised by the amount of random information that I learnt from this episode. Such as the origin of the phrase ‘saved by the bell’ and the cultural origin of vampires; something I thought was completely originated in fiction.

Echoes

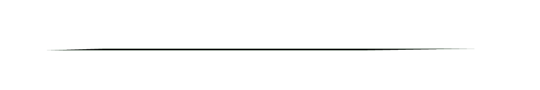

Dr Walter Freeman is the father of the icepick lobotomy. He believes the ten-minute procedure will all but end the need for the mental hospital. He has the best of intentions but winds up creating an entirely new kind of horror story.

I didn’t think it was possible to go from not knowing who someone was to hating them in the span of twenty minutes, but this episode did just that. Though this episode wasn’t the most entertaining, it provided an insight in a practise that I thought was long dead by the fifties.

Black Stockings

In 19th century Ireland, folklore has a strong hold. Michael Cleary is convinced his wife, Bridget, has been replaced by a fairy called a changeling. And his belief drives him to the most extreme act.

This is the highest rated episode of the series and I understand why. That being said, I don’t have much to say about this episode as I don’t remember most of the information it presented; which may mean that I didn’t enjoy it too much.

Passing Notes

In 19th century America, at the height of the Spiritualist Movement, a haunted house is not just the stuff of ghost stories. Many believe the dead can talk and, sometimes, will come back from the other side to wreak havoc on the living.

This episode is my second favourite of the first season and the last episode I watched; as I somehow managed to skip it. I feel, as more episodes cover similar phenomena, I should preface that I don’t believe in ghosts, demons, or anything else of that kind. That being said, I thoroughly enjoyed this episode.

The Beast Within

Werewolves are now movie monsters. But they were once thought to be all too real. In 1589, villagers in Bedburg, Germany, are convinced that werewolf is killing women and children only to discover the killer is really one of their own.

This episode covers the origin of another fictional legend, werewolves. While I somewhat enjoyed this episode, I wish the origins of a silver bullet being able to kill a werewolf had been covered in the episode; even though they have no relation to The Werewolf of Bedburg.

Unboxed

Robert Gene Otto is a child without friends. That is, until he received a doll as a gift. He names the doll after himself, Robert. They become fast friends and soon the boy believes the doll is real. But to everyone else…Robert the Doll is a curse.

Robert the Doll is an entity that genuinely spooks me, not because of any supernatural reasons, but simply because he looks gross. This is my favourite episode of the series as it covered a topic that I already knew parts of, but also revealed information that I didn’t know.

It should be stated here that Season 2 takes a completely different approach to Season 1 as it turns from a combination of dramatisations and documentary footage to strictly cinematic portrayals of spooky historical events.

In The Name of Science

Two shunned Irish immigrant in Scotland start off as grave robbers to sell the dead to doctors, but decide that creating their own inventory is much easier, and become the most prolific mass-murdering due in history.

Thanks to my obsession with Horrible Histories, both the books and the TV series, in my younger years I already knew the full story of Burke and Hare. Unfortunately, that made this episode almost unbearable to watch; its extended runtime of 50 minutes didn’t help either.

Mirror, Mirror

The ageing Countess of Blood, running out of virginal peasants to drain of their youthful essence, brings in a bright-eyed noble to start a new cycle of torture and murder.

The first thing I noticed upon starting this episode was the drastically different runtime from the previous episode, a meagre 20 minutes. This is a recurring issue with the second season that I will elaborate further in my final thoughts. Another issue with this episode is that I didn’t know who Elizabeth Bathory was before I started this episode, and frankly I still don’t care.

Ghosts in the Attic

In the German hinterlands, between World Wars, a family goes to bed, not knowing that their killer has been living in the walls and attics of their home like a ghost, watching, waiting for his chance to strike, in one of the most famous unsolved mysteries of all time.

Much like almost every other episode in this season, this episode is extremely boring and slow paced. It doesn’t help that the acting in this episode isn’t great either.

The Curse of the Orloj

As two clockmakers race against the curse of the Orloj, a curse that has already driven the city of Prague to madness and death with the Black Plague, these brothers will discover the price of trying to change history.

There are three words to perfectly surmise my thoughts towards this episode: I don’t care. I uttered this phrase under my breath almost every ten minutes and I kept checking the runtime to see how much of this I had to bear until it was over. If these two things don’t tell you how much I despise this episode, I don’t know what will.

The Witch of Hadley

A young woman, raised in a town controlled by a religious zealot, must rectify a fatal mistake before a ravenous mob hangs the Old Witch, Mary Webster, in this story set just 11 years before and 100 miles from Salem, Massachusetts.

First off, Mary Webster was already covered briefly in season 1 where a character says “you are haunted by Goody Basset, a witch hung the 6020s” . That’s all you need to know about her, so why did they make a fifty minute episode elaborating on a single sentence? Not to mention that Mary Webster doesn’t have anything to do with the Salem Witch Trials and the fact that she was killed 11 years and 100 miles away from them is pure coincidence.

The Devil and the Divine

In 1922 only one person, Jack Parsons, believed that we would send a rocket into space and conjure a demon. By 1952 he had done both. But all he cared about was the Scarlet Woman he had both summoned, and lost, Marjorie Cameron.

Here we are that the only good episode in season 2. The main reasons I covet this episode so much higher above the others is because it’s a well-made episode and it isn’t mind-numbingly boring.

Final Thoughts:

Season 1 what great, Season 2 was terrible

The runtimes for Season Two’s episodes were inconsistent ranging from anywhere between twenty and sixty minutes

Did I like this show? Season One, yes. Season Two, no.

Will I continue watching? As Lore hasn’t been renewed for a third season, I can’t continue watching it, but I will give the podcast a chance.

0 notes

Text

#343 December 11, 2018

Matt writes: In order to celebrate five years of Scout Tafoya's acclaimed series of video essays entitled, "The Unloved," we are presenting his new feature-length essay: "Beata Virgo Viscera." Click here to read Scout's piece on what inspired the following film, which you can watch in its entirety below.

In honor of Jon S. Baird's upcoming awards contender "Stan & Ollie," starring the perfectly cast duo of Steve Coogan and John C. Reilly, enjoy the three Laurel & Hardy classics linked at the end of this newsletter.

vimeo

Trailers

Stan & Ollie (2018). Directed by Jon S. Baird. Written by Jeff Pope. Starring Steve Coogan, John C. Reilly, Shirley Henderson. Synopsis: Laurel and Hardy, the world's most famous comedy duo, attempt to reignite their film careers as they embark on what becomes their swan song - a grueling theatre tour of post-war Britain. Opens in US theaters on December 28th, 2018.

youtube

Artemis Fowl (2019). Directed by Kenneth Branagh. Written by Michael Goldenberg, Adam Kline and Conor McPherson (based on the book by Eoin Colfer). Starring Hong Chau, Miranda Raison, Nonso Anozie. Synopsis: Artemis Fowl II, a young Irish criminal mastermind, kidnaps the fairy LEPrecon officer Holly Short for ransom to fund the search for his missing father in order to restore the family fortune. Opens in US theaters on August 9th, 2019.

youtube

All Is True (2019). Directed by Kenneth Branagh. Written by Ben Elton. Starring Kenneth Branagh, Judi Dench, Ian McKellen. Synopsis: A look at the final days in the life of renowned playwright William Shakespeare. US release date is TBA.

youtube

The Standoff at Sparrow Creek (2019). Written and directed by Henry Dunham. Starring James Badge Dale, Patrick Fischler, Brian Geraghty. Synopsis: A former cop-turned-militia man investigates a shooting at a police funeral. US release date is TBA.

youtube

Sunset (2019). Directed by László Nemes. Written by László Nemes, Clara Royer and Matthieu Taponier. Starring Susanne Wuest, Vlad Ivanov, Urs Rechn. Synopsis: A young girl grows up to become a strong and fearless woman in Budapest before World War I. US release date is TBA.

youtube

Happy as Lazzaro (2018). Written and directed by Alice Rohrwacher. Starring Adriano Tardiolo, Agnese Graziani, Luca Chikovani. Synopsis: This is the tale of a meeting between Lazzaro, a young peasant so good that he is often mistaken for simple-minded, and Tancredi, a young nobleman cursed by his imagination. Now available on Netflix.

youtube

State Like Sleep (2019). Written and directed by Meredith Danluck. Starring Katherine Waterston, Michiel Huisman, Michael Shannon. Synopsis: A woman grapples with the consequences of her celebrity husband's double life after he commits suicide. Opens in US theaters on January 4th, 2019.

youtube

Rust Creek (2019). Directed by Jen McGowan. Written by Julie Lipson. Starring Hermione Corfield, Denise Dal Vera, Jeremy Glazer. Synopsis: An overachieving college student gets lost on her way to a job interview. A wrong turn leaves her stranded deep in the Kentucky forest. US release date is TBA.

youtube

The Heiresses (2019). Written and directed by Marcelo Martinessi. Starring Ana Brun, Margarita Irun, Ana Ivanova. Synopsis: An ex-convict working undercover intentionally gets himself incarcerated again in order to infiltrate the mob at a maximum security prison. US release date is TBA.

youtube

The Aftermath (2019). Directed by James Kent. Written by Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse (based on the novel by Rhidian Brook). Starring Alexander Skarsgård, Keira Knightley, Jason Clarke. Synopsis: Post World War II, a British colonel and his wife are assigned to live in Hamburg during the post-war reconstruction, but tensions arise with the German who previously owned the house. Opens in US theaters on April 26th, 2019.

youtube

After (2019). Directed by Jenny Gage. Written by Susan McMartin (based on the novel by Anna Todd). Starring Hero Fiennes Tiffin, Josephine Langford, Selma Blair. Synopsis: A young girl falls for a guy with a dark secret and the two embark on a rocky relationship. Opens in US theaters on April 12th, 2019.

youtube

Watership Down (2018). Directed by Noam Murro. Written by Richard Adams and Tom Bidwell. Starring James Alexander, Gemma Arterton, John Boyega. Synopsis: Fleeing their doomed warren, a colony of rabbits struggle to find and defend a new home. Premieres on the BBC on December 22nd, 2018.

youtube

Happy Death Day 2U (2019). Written and directed by Christopher Landon. Starring Jessica Rothe, Ruby Modine, Israel Broussard. Synopsis: Sequel to the 2017 film 'Happy Death Day.' Opens in US theaters on February 14th, 2019.

youtube

Vox Lux (2018). Written and directed by Brady Corbet. Starring Raffey Cassidy, Natalie Portman, Jude Law. Synopsis: An unusual set of circumstances brings unexpected success to a pop star. Now playing in US theaters.

youtube

Welcome to Marwen (2018). Directed by Robert Zemeckis. Written by Robert Zemeckis and Caroline Thompson. Starring Steve Carell, Leslie Mann, Eiza González. Synopsis: A victim of a brutal attack finds a unique and beautiful therapeutic outlet to help him through his recovery process. Opens in US theaters on December 21st, 2018.

youtube

Captain Marvel (2019). Directed by Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck. Written by Anna Boden, Ryan Fleck, Geneva Robertson-Dworet and Jac Schaeffer (based on the comics by Roy Thomas and Gene Colan). Starring Brie Larson, Jude Law, Gemma Chan. Synopsis: Carol Danvers becomes one of the universe's most powerful heroes when Earth is caught in the middle of a galactic war between two alien races. Opens in US theaters on March 8th, 2019.

youtube

Avengers: Endgame (2019). Directed by Anthony Russo and Joe Russo. Written by Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely (based on the comics by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby). Starring Robert Downey Jr., Chris Evans, Josh Brolin. Synopsis: The fourth installment of the 'Avengers' series. Opens in US theaters on April 26th, 2019.

youtube

The Lion King (2019). Directed by Jon Favreau. Written by Jeff Nathanson. Starring James Earl Jones, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Donald Glover. Synopsis: CGI re-imagining of the 1994 Disney classic. Opens in US theaters on July 19th, 2019.

youtube

Peter Hedges on "Ben is Back"

Matt writes: Peter Hedges, the Oscar-nominated writer of "What's Eating Gilbert Grape" and "About a Boy," recently spoke with me about directing his son Lucas in the new drama, "Ben is Back," also starring Julia Roberts. Read our full conversation here.

2018 Key West Film Festival

Matt writes: Our critic Monica Castillo reports on her adventures at Florida’s Key West Film Festival and the special meaning that the experience held for her. Click here for the full article.

Free Movies

Busy Bodies (1933). Directed by Lloyd French. Starring Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, Dick Gilbert. Synopsis: Stan and Ollie do battle with inanimate objects, their co-workers, and the laws of physics during a routine work day at the sawmill.

Watch "Busy Bodies"

Babes in Toyland (a.k.a. March of the Wooden Soldiers) (1934). Directed by Gus Meins and Charley Rogers. Written by Frank Butler and Nick Grinde. Starring Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, Virginia Karns. Synopsis: Opposing the evil Barnaby, Ollie Dee and Stanley Dum try and fail to pay-off Mother Peep's mortgage and mislead his attempts to marry Little Bo. Enraged, Barnaby's boogeymen are set on Toyland.

Watch "Babes in Toyland"