#could be further showing Galadriel’s goodness/light to the point of divinity

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Phial of Galadriel

Ok so I just finished The Two Towers in my re-read and reviewed some silm passages for reference. Thoughts inspired by @partfae and @elladanns posts on Galadriel as a “dark witch” and how the pj films led to some misunderstandings about her character.

A long, long time ago, there were Two Trees, basically made of pure light. They were created by Yavanna, one of the Valar. The trees and their light were Good with a capital G and Feanor crafted his Simarils to reflect their light. It was said that Galadriel’s hair was so Light and Gold it looked like it had “caught in a mesh the radiance of” one of the trees.

Ungoliant represents the opposite of all of that. She is more than Dark, she is Nothing- a Void that devours all Light and Beauty. (I’m talking with capitals because these things in the story seem to represent Concepts for Tolkien). Melkor, another of the Valar, teams up with Ungoliant to destroy the trees. She drinks up all of their light, and then asks Melkor for the Silmarils, which he had captured. Ungoliant craves beautiful light and she’s powerful enough to overwhelm it.

Fast forward to the Third Age. Galadriel, lady of Lorien, bearer of a Ring of Power, after defying the Valar in pursuit of the lost Silmarils in the First Age, crafts a Phial and gives it to Frodo. She captures the Light of a Silmaril (Eärendil’s Star) for this Phial.

So far, Frodo and Sam have used it in two places. First, Frodo grasps the Phial when the Witch-King of Angmar is exerting his will over Frodo to put on the One Ring, and it enables him to resist.

Second, the Light drives away Shelob, who we read is the last child of Ungoliant. Shelob seems to have the same powers of Darkness and Void, and Frodo and Sam remark on the unnatural dark in her tunnel. They starts losing other senses as well. When Frodo first uses the phial, he cries, “Hail Eärendil, brightest of stars!” Shelob has apparently heard this thousands of times and doesn’t flinch. But when he calls Galadriel’s name, she pauses.

When Sam uses the Phial, he uses a few lines from a song dedicated to Varda, another of the Valar and the Lady of Stars. This, coupled with his “indomitable spirit” sets the Phial ablaze and drives Shelob completely away.

There are a few things that I find interesting about this. One, Galadriel, who once rebelled against the Valar with Feanor to pursue the Silmarils, now has gifted the light of a Silmaril to the Ringbearer, and it is set ablaze through praise of a Vala. That seems like an important evolution for her. Second, the Light of the Phial is enough to dramatically hurt Shelob, whereas Ungoliant devoured the Trees themselves. That could just be due to a difference in power between Shelob and her mother but it still stands out.

Galadriel’s magic here is so Light, and so powerful *because* of its light. It’s also stronger than that of the “witch”- the morgul-king.

#galadriel#lord of the rings#the phial of Galadriel#silmarillion#lotr meta#i’m also extremely interested to know if tolkien believed in speaking in tongues as a gift of the spirit#because both Frodo and Sam do it when they use the phial#could be further showing Galadriel’s goodness/light to the point of divinity

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

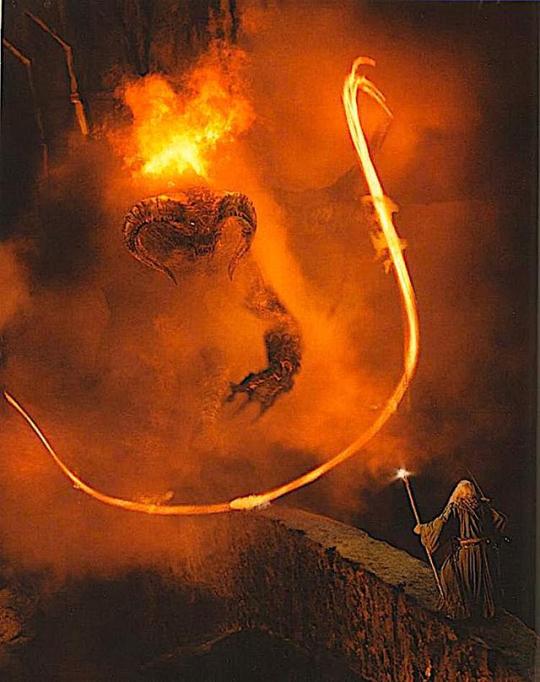

Images from The Fellowship Of The Ring, courtesy of New Line Cinema

THE LORD OF THE RINGS is a vast tapestry combining huge events, gripping conflict, intense emotions, and timeless themes of heroism, temptation, romance, sacrifice and redemption. Peter Jackson's epic production still stands as the greatest fantasy in film history. The final part of the trilogy was released 15 years ago today; and so in honor of this auspicious occasion, Multi Facet Fables presents David D. Fowler's extended appreciation of this fantasy masterpiece.

This piece was written in 2005, after the release of the trilogy's final Extended Edition, and then updated after the release of The Hobbit. Rather than assessing the original trilogy as three separate films, as most reviewers have done, this evaluation explores how well it succeeds in telling one continuous, self-contained story. The critique is presented in three parts; and to enhance your appreciation of the film, at the end you will also find our Appendices, featuring an archive of Rings-related videos.

ARWEN’S CHOICE, GRIMA’S TEAR – part 1

Jackson’s Christian Vision

Yea, now that the dust of Mount Doom has long settled upon the plains of Mordor, and the Dark Lord’s dire shadow has verily been banished from the big screens of Middle-Earth lo these many years, we must needs contemplate anew the fall of the tyrant Sauron in our home palantirs.

“This tale grew in the telling,” J.R.R. Tolkien famously wrote in the foreword of The Lord Of The Rings, the centerpiece of his Middle-Earth saga. In director Peter Jackson’s hands, Tolkien’s tale has grown into a vision beyond all expectations. This becomes clearer the more one views Jackson’s marvelous extended editions of his Rings trilogy.

Many have reviewed the individual installments of the theatrical film, of course; and there have been reviews of the extended DVDs – but nothing terribly in-depth, it would seem. Generally, the components of the trilogy have been evaluated as separate works. I have seen dozens of articles on the subject, but have never encountered any detailed evaluations of how the movie as a whole holds up, considered as a single entity. This is one attempt to answer that question. I have also chosen to emphasize the film’s spiritual qualities, which are myriad. The film is rife with Christian mythology and symbolism – which, as I will establish later, appears to be quite intentional.

Christian Critics

The Lord Of The Rings has rightly been extolled by Christian reviewers such as Steven D. Greydanus of Decent Films, and Sister Rose Pacatte of Sister Rose Movies. Many have showed some real appreciation of what Jackson has accomplished. However, it seems to me that most Christian critics have only scratched the surface of this film’s implicitly biblical content; they have focused on obvious elements, such as self-sacrifice and the struggle against evil.

Several of those who have delved a little deeper have found the film spiritually wanting to some degree or other – generally concluding that, because the film’s makers are not known to be believers, therefore they had only limited understanding of the book’s Christian content. But if Jackson and co-scripters Frances Walsh and Philippa Boyens are indeed not Christians, it is verging on the miraculous that they caught so much of the book’s spiritual content – and, dare I say it, even improved upon Tolkien in some places.

Would the Bible-thumping naysayers have preferred that only card-carrying Christians be allowed to adapt Tolkien’s sacred ‘textus receptus’? This massive production got precisely what it needed: supremely imaginative filmmakers. If it had been left to merely ‘Christian’ filmmakers, who among that exalted coterie could have pulled off this trilogy? Mel Gibson, perhaps? Too dogmatic, and way too much baggage. Wim Wenders? Promising, but his style’s a tad too introspective. Andrei Tarkovsky? Unfortunately, he’s dead – but the possibilities boggle the mind, nonetheless. The Left Behind guys? Fuggeddaboudit!

Non-Biblical Behavior

I don’t wanna scare ya, kiddies, but imagine for a moment a Rings trilogy done as a Ted Baehr-approved production. Keep in mind that Care-Baehr’s online Movieguide very kindly alerts good little Christians about all manner of immoral, non-biblical behavior lurking at the local cineplex; and also take note that their review of Jackson’s movie warned the born-again public to watch out for such things as the film’s “implied alcohol consumption”.

If the Baehr-brains had produced a film consistent with their peculiar creed, we would’ve had hobbits bereft of pipeweed (the devil’s playground!); a moratorium on pubs (be not drunk with ale!); no silly songs (idle foolishness!); no garrulous dwarves (coarse jesting!); no prophetic intonations from Galadriel (occult divination!); no haughty elves (spiritual pride!); no talking trees (substance abuse!); and no resurrection of Gandalf (implied offscreen nudity!). Oh – and no, um, sorcery (!!!!!). But I digress.

No-Budget

Jackson’s earliest films give no indication of the greatness to come. The New Zealand auteur started with a no-budget, moronic alien invasion flick, Bad Taste (1987), which more than lived up to its name. He progressed (so to speak) to Meet The Feebles (1989), an over-the-top Muppet Show satire starring extremely naughty puppets; and outdid himself with the zombie fest, Braindead (1993), aka Dead Alive – touted as the goriest film of all time. Fortunately, he developed ambitions to move beyond such limited fare.

In 1994, by now partnered artistically (and domestically) with Fran Walsh, Jackson produced the superb Heavenly Creatures. Based on a notorious 1950s New Zealand murder case, it was an extraordinary depiction of two troubled teenage girls – who created a bizarre fantasy world, which spiraled out of control. This was followed by Forgotten Silver (1995), a brilliant ‘mockumentary’ about a mythical pioneer of New Zealand’s film industry; and The Frighteners (1996) a skillful horror/comedy with state-of-the-art special effects.

Jackson had proven his artistic credentials, but had never had a hit. To their everlasting credit, the New Line Cinema executives took a big chance by accepting his proposal to direct Tolkien’s classic; the result, by any standards, is an unprecedented epic, dwarfing (sorry) all previous fantasy films. While I wouldn’t go so far as to call Jackson a visionary, it is clear that he has taken Tolkien’s phenomenal vision and truly worked wonders with it. Viewing the complete extended edition, we can fully appreciate the scope of his achievement; and thanks to the various DVD documentary extras, we can also marvel at the sheer magnitude of this production.

No Sequels

Before I proceed further, a minor point must be stressed. Some critics still insist on referring to the Rings Trilogy as a three-hour hit movie (The Fellowship Of The Ring) plus two sequels (The Two Towers and The Return Of The King). They forget that Tolkien never intended the story to be split up; that was the publisher’s idea. While some reviewers have evaluated the individual theatrical films in detail, most assessments of the extended versions have amounted to little more than laundry lists of the extra scenes; the films have generally been appreciated as separate entities, but not as parts of a whole.

This is unfortunate, considering that The Lord Of The Rings is one of the most important films ever made; it deserves to be evaluated as the director intended it: as one single, self-contained tapestry. Jackson has emphasized that he considers it one cohesive story, in three acts. This is how I am approaching the film in this critique; I am also writing for those who are at least familiar with the theatrical version (otherwise, beware of spoilers!)

Minor Flaws

Jackson’s film has its flaws. There are a few redundancies, such as the several mentions of Bilbo’s book title; and some inconsistencies – as when Merry and Eowyn, who are supposed to be hiding their presence in the army from Theoden and Eomer, hang out casually with the other soldiers without making any effort to cover their faces. There are also some unnecessary scenes, such as the ‘drinking game’ between Legolas and Gimli; and speaking of well-tossed dwarves, Gimli is used too often for comic relief. The killing contests between Leggy and Gimli are played for laughs, as are a few too many other moments in battle scenes.

In one improbable sequence, two guards fail to notice a clumsy and noisy Pippin spilling oil as he attempts to light the Minas Tirith beacon. There is also at least one glaring continuity error: the magic disappearing barrels in Faramir’s cave hideout. You see the barrels behind Frodo and Sam for several shots; but when Faramir enters to interrogate them, the barrels are nowhere to be seen. (Now, whenever I see Sam urging the Ring Bearer to “disappear” moments before Faramir’s entrance, I keep thinking all Frodo needs to do is jump into one of those barrels). There are also a few too many ‘near death experiences’ – i.e. characters thinking their loved ones have been killed, only to find they have miraculously survived.

In addition, one could accuse Jackson of false advertising. There were several very nice scenes in various previews which never made it into the final film: two elf maidens running through the woods, laughing; Aragorn and Arwen frolicking, as she smiles radiantly; Arwen exhorting Elrond to give Aragorn “the sword of the king”; Elrond telling Arwen “You gave away your life’s grace; I can no longer protect you,” and then sadly embracing his dying daughter. Not nice to tease one’s loyal fans; more importantly, all of these scenes could have easily been added to the finished product – and should have been.

Whither Bombadil?

Further, what of the scriptwriters’ myriad changes to Tolkien’s sacred, inviolable text? Well, to those dedicated keepers of the Flame of the West, who have frequently and loudly bemoaned the absence of Tom Bombadil, Glorfindel, Ghan-buri-ghan, Imrahil, Radagast the Brown, the knights of Dol Amroth, the Sceptre of Arnor and the Scouring of the Shire, one can only bow the head sympathetically and say ... (wait for it) ... Get a fricking life, fanboys!!!! Think you could’ve done a better job?

Have these people never heard of artistic license? Jackson has always stressed that this film is merely his interpretation of Tolkien’s masterwork. Some of these grumblers evidently have little or no understanding of the structural and dramatic requirements of film, as opposed to literature; nor much grasp of the process of adaptation, and the fact that compression of material is essential in something of this magnitude. Even given the film’s 11-and-a-half hour length, omissions were unavoidable.

There are, indeed, key differences between book and film: Frodo is rescued from the Black Riders by Arwen; Frodo rejects Sam, and orders him to go back to the Shire; the two hobbits are sidetracked to battle-torn Osgiliath; Aragorn is almost killed by wargs; the ghostly warriors from the Paths of the Dead join the battle at Minas Tirith; a spellbound Frodo offers the One Ring to one of the Nazgul; a legion of elves help defend Helm’s Deep; Shelob attacks Frodo in the third act, not the second; Faramir tries to take the Ring from Frodo; and there is a significant twist to Frodo’s final confrontation with Gollum.

And your friendly neighborhood purists could probably list many more – to the extent that some have even felt compelled to make their own bootleg versions of the films – such as the Feanor Edition of The Two Towers, and the Sharkey Purist Edition of the entire trilogy. Certainly, Jackson’s choices should be debated. But I think they generally make sufficient dramatic sense, in the context of the film adaptations.

Improving On Tolkien

Some changes, in fact, are even improvements. For example, Tolkien has Merry and Pippin surprise Frodo by insisting on accompanying him when he leaves the Shire; Jackson instead has Leggy and Gimli surprise Aragorn as he leaves to embark on the Paths of the Dead – thus showing Aragorn’s friends as being willing to brave supernatural terror. As for the book’s Scouring of the Shire, using that lengthy section as the concluding battle of the film would have been very anti-climactic after already showing the source of ultimate evil destroyed; instead, this event is depicted briefly in a vision, as a possible future if the Ring is not destroyed.

In act one of the book, wargs threaten the Fellowship briefly at night, as the comrades travel toward Moria; the lead beast attacks, and is quickly dispatched by Legolas; the ineffectual creatures soon back down, never to be seen again. Jackson makes much better use of the creatures, moving the wargs to the middle act, when they attack the citizens of Edoras as they journey to the refuge at Helm’s Deep; the director takes the opportunity to stage a full-blown battle. There is now much more at stake: rather than just menacing the hardy fellowship, the wargs threaten to massacre women and children.

One can quibble about some of the film-makers’ other changes and additions to the plot. But the extensive commentaries and documentaries accompanying the DVDs clarify their reasons – which are generally good ones. For example, Tolkien’s Faramir is never tempted to take the One Ring – which is hardly the stuff of suspenseful drama. The initial motives and inner turmoil of the film’s Faramir add to the dramatic tension; and unlike his brother Boromir, this Faramir ultimately overcomes his fall from grace, decisively rejecting the Ring. Granted, that’s a serious change from the book. But the concept of the stalwart, noble knight who resists the Ring’s temptation is already in the film, in the form of Aragorn. It's not really necessary to make that point with two different characters. So why not utilize Faramir as a means of emphasizing the evil power of the ring? I don’t think this change harms the overall story in any way.

Sunrise

Truly, all the whinging purists bogged down in the dead marshes of their dashed expectations can’t spoil my enjoyment of what Jackson and his team have done. Such critics are like Bilbo’s trolls, so busy “arguing the whithertos and whyfors” that they fail to see the sunrise coming. And what a magnificent sunrise this film is. The Lord Of The Rings is, far and away, the very finest film adaptation of an epic book that I’ve ever seen – even surpassing David Lynch’s superlative interpretation of Dune. The merits of the film virtually eclipse its flaws. That may sound like hyperbole, but I believe it’s warranted in this case.

Click here for part 2:

http://musemash.tumblr.com/post/181194366715/images-from-the-two-towers-courtesy-of-new-line

0 notes