#coronavirus test kit

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

From shortages to surplus, to clearance sale...

I'm getting some shopping done, and I felt like I should grab this moment while it was there.

As many (test kits) as you want, $10 per packet.

My guess is that this stock is within 6 months of expiry date.

Fresh stock now doubt retails higher. Just interesting how the first issue of these was limited to medical staff, big corporations (and a vague memory of some obnoxiously rich barstards).

Finally got another booster shot, turned out it was my fourth booster. I'd lost track of how many, but as it has been over 18 months or so, memory drift is inevitable.

Got my little badge, promoting a version of vaccination jingoism.

Oooh, nice badge. I only picked it up as a token for this blog. As a valuable token, I can imagine it will remain virtually worthless for, well, forever.

Having said all that, I still see reports of covid spreader infections at events (American based so far) .

As for post jab, for the first time, I had symptoms other than soreness at the injection site; joint aches (slight but noticeable) and a headache (low range but annoying) which required some panadol and an early nights sleep.

I still see the occasional low stock of toilet paper, no more barren shelves though.

Covid is now a 'in other news, covid variant (xyz123) has been detected in....' in place of the universal bogeyman headlining the first half of news. Since the vaccine roll out, it is now a non-memory. Those years did, and did not, happen. Just a time of fear, confusion, uncertainty and isolation.

For those who have 'Long Covid' - the chronic after effects, it's more like 'before and after covid' I used to enjoy better health.

I suppose perspective is dependent upon proximity.

24 September 2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

Genabio COVID-19 Rapid Self-Test Kit ===

CLICK TO BUY

0 notes

Text

Article Date: March 10, 2025

You can no longer order free COVID-19 tests from the United States government. As of March 10, the government's free coronavirus test distribution program, COVIDtests.gov, is not currently accepting orders, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response website says. Previously, every American household was eligible to order four free at-home COVID test kits, which were shipped to your home through the U.S. Postal Service at zero cost. "Tests ordered before 8:00 PM EDT, Sunday, March 9, 2025, will be shipped," the ASPR website says. The free COVID test distribution program started in 2021. Since then, more than 900 million free COVID tests have been mailed to households in the U.S., and some 900 million have been distributed to community centers, libraries, nursing homes, and food banks, TODAY.com previously reported.

#news#us news#covid news#coronavirus#covid#covid 19#covid-19#still coviding#covid isn't over#covid testing#uspol#us politics

456 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved in our archive

By Vijay Kumar Malesu

In a recent pre-print study posted to bioRxiv*, a team of researchers investigated the predictive role of gut microbiome composition during acute Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in the development of Long Coronavirus Disease (Long COVID) (LC) and its association with clinical variables and symptom clusters.

Background LC affects 10–30% of non-hospitalized individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2, leading to significant morbidity, workforce loss, and an economic impact of $3.7 trillion in the United States (U.S.).

Symptoms span cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, cognitive, and neurological issues, resembling myalgic encephalomyelitis and other post-infectious syndromes. Proposed mechanisms include immune dysregulation, neuroinflammation, viral persistence, and coagulation abnormalities, with emerging evidence implicating the gut microbiome in LC pathogenesis.

Current studies focus on hospitalized patients, limiting generalizability to milder cases. Further research is needed to explore microbiome-driven predictors in outpatient populations, enabling targeted diagnostics and therapies for LC’s heterogeneous and complex presentation.

About the study The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and recruited adults aged 18 years or older who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing at Mayo Clinic locations in Minnesota, Florida, and Arizona from October 2020 to September 2021. Participants were identified through electronic health record (EHR) reviews filtered by SARS-CoV-2 testing schedules.

Eligible individuals were contacted via email, and informed consent was obtained. Of the 1,061 participants initially recruited, 242 were excluded due to incomplete data, failed sequencing, or other issues. The final cohort included 799 participants (380 SARS-CoV-2-positive and 419 SARS-CoV-2-negative), providing 947 stool samples.

Stool samples were collected at two-time points: weeks 0–2 and weeks 3–5 after testing. Samples were shipped in frozen gel packs via overnight courier and stored at −80°C for downstream analyses. Microbial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted using Qiagen kits, and metagenomic sequencing was performed targeting 8 million reads per sample.

Taxonomic profiling was conducted using Kraken2, and functional profiling was performed using the Human Microbiome Project Unified Metabolic Analysis Network (HUMAnN3).

Stool calprotectin levels were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) was detected using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

Clinical data, including demographics, comorbidities, medications, and symptom persistence, were extracted from EHRs.

Machine learning models incorporating microbiome and clinical data were utilized to predict LC and to identify symptom clusters, providing valuable insights into the heterogeneity of the condition.

Study results The study analyzed 947 stool samples collected from 799 participants, including 380 SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals and 419 negative controls. Of the SARS-CoV-2-positive group, 80 patients developed LC during a one-year follow-up period.

Participants were categorized into three groups for analysis: LC, non-LC (SARS-CoV-2-positive without LC), and SARS-CoV-2-negative. Baseline characteristics revealed significant differences between these groups. LC participants were predominantly female and had more baseline comorbidities compared to non-LC participants.

The SARS-CoV-2-negative group was older, with higher antibiotic use and vaccination rates. These variables were adjusted for in subsequent analyses.

During acute infection, gut microbiome diversity differed significantly between groups. Alpha diversity was lower in SARS-CoV-2-positive participants (LC and non-LC) than in SARS-CoV-2-negative participants.

Beta diversity analyses revealed distinct microbial compositions among the groups, with LC patients exhibiting unique microbiome profiles during acute infection.

Specific bacterial taxa, including Faecalimonas and Blautia, were enriched in LC patients, while other taxa were predominant in non-LC and negative participants. These findings indicate that gut microbiome composition during acute infection is a potential predictor for LC.

Temporal analysis of gut microbiome changes between the acute and post-acute phases revealed significant individual variability but no cohort-level differences, suggesting that temporal changes do not contribute to LC development.

However, machine learning models demonstrated that microbiome data during acute infection, when combined with clinical variables, predicted LC with high accuracy. Microbial predictors, including species from the Lachnospiraceae family, significantly influenced model performance.

Symptom analysis revealed that LC encompasses heterogeneous clinical presentations. Fatigue was the most prevalent symptom, followed by dyspnea and cough.

Cluster analysis identified four LC subphenotypes based on symptom co-occurrence: gastrointestinal and sensory, musculoskeletal and neuropsychiatric, cardiopulmonary, and fatigue-only.

Each cluster exhibited unique microbial associations, with the gastrointestinal and sensory clusters showing the most pronounced microbial alterations. Notably, taxa such as those from Lachnospiraceae and Erysipelotrichaceae families were significantly enriched in this cluster.

Conclusions To summarize, this study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals who later developed LC exhibited distinct gut microbiome profiles during acute infection. While prior research has linked the gut microbiome to COVID-19 outcomes, few studies have explored its predictive potential for LC, particularly in outpatient cohorts.

Using machine learning models, including artificial neural networks and logistic regression, this study found that microbiome data alone predicted LC more accurately than clinical variables, such as disease severity, sex, and vaccination status.

Key microbial contributors included species from the Lachnospiraceae family, such as Eubacterium and Agathobacter, and Prevotella spp. These findings highlight the gut microbiome’s potential as a diagnostic tool for identifying LC risk, enabling personalized interventions.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Journal reference: Preliminary scientific report. Isin Y. Comba, Ruben A. T. Mars, Lu Yang, et al. (2024) Gut Microbiome Signatures During Acute Infection Predict Long COVID, bioRxiv. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.10.626852. www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.12.10.626852v1.full

#mask up#public health#wear a mask#pandemic#wear a respirator#covid#still coviding#covid 19#coronavirus#sars cov 2#long covid#AI

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

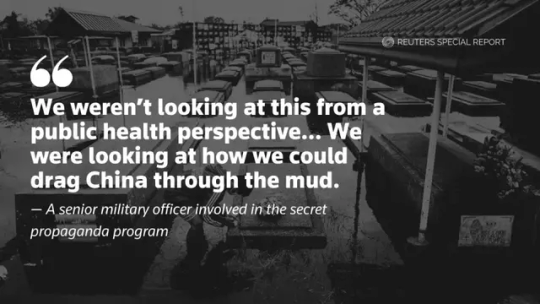

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-covid-propaganda/

The U.S. military launched a clandestine program amid the COVID crisis to discredit China’s Sinovac inoculation – payback for Beijing’s efforts to blame Washington for the pandemic. One target: the Filipino public. Health experts say the gambit was indefensible and put innocent lives at risk.

@startorrent02 @dirhwangdaseul @chrisdornerfanclub @commiemartyrshighschool @commiekinkshamer

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. military launched a secret campaign to counter what it perceived as China’s growing influence in the Philippines, a nation hit especially hard by the deadly virus.

The clandestine operation has not been previously reported. It aimed to sow doubt about the safety and efficacy of vaccines and other life-saving aid that was being supplied by China, a Reuters investigation found. Through phony internet accounts meant to impersonate Filipinos, the military’s propaganda efforts morphed into an anti-vax campaign. Social media posts decried the quality of face masks, test kits and the first vaccine that would become available in the Philippines – China’s Sinovac inoculation.

Reuters identified at least 300 accounts on X, formerly Twitter, that matched descriptions shared by former U.S. military officials familiar with the Philippines operation. Almost all were created in the summer of 2020 and centered on the slogan #Chinaangvirus – Tagalog for China is the virus.

Translation from Tagalog

#ChinaIsTheVirus

Do you want that? COVID came from China and vaccines came from China

(Beneath the message is a picture of then-Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte saying: “China! Prioritize us first please. I’ll give you more islands, POGO and black sand.” POGO refers to Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators, online gambling companies that boomed during Duterte’s administration. Black sand refers to a type of mining.)

“COVID came from China and the VACCINE also came from China, don’t trust China!” one typical tweet from July 2020 read in Tagalog. The words were next to a photo of a syringe beside a Chinese flag and a soaring chart of infections. Another post read: “From China – PPE, Face Mask, Vaccine: FAKE. But the Coronavirus is real.”

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pentagon ran secret anti-vax campaign to undermine China during pandemic

CHRIS BING and JOEL SCHECTMAN at Reuters:

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. military launched a secret campaign to counter what it perceived as China’s growing influence in the Philippines, a nation hit especially hard by the deadly virus. The clandestine operation has not been previously reported. It aimed to sow doubt about the safety and efficacy of vaccines and other life-saving aid that was being supplied by China, a Reuters investigation found. Through phony internet accounts meant to impersonate Filipinos, the military’s propaganda efforts morphed into an anti-vax campaign. Social media posts decried the quality of face masks, test kits and the first vaccine that would become available in the Philippines – China’s Sinovac inoculation. Reuters identified at least 300 accounts on X, formerly Twitter, that matched descriptions shared by former U.S. military officials familiar with the Philippines operation. Almost all were created in the summer of 2020 and centered on the slogan #Chinaangvirus – Tagalog for China is the virus.

“COVID came from China and the VACCINE also came from China, don’t trust China!” one typical tweet from July 2020 read in Tagalog. The words were next to a photo of a syringe beside a Chinese flag and a soaring chart of infections. Another post read: “From China – PPE, Face Mask, Vaccine: FAKE. But the Coronavirus is real.”

After Reuters asked X about the accounts, the social media company removed the profiles, determining they were part of a coordinated bot campaign based on activity patterns and internal data.

The U.S. military’s anti-vax effort began in the spring of 2020 and expanded beyond Southeast Asia before it was terminated in mid-2021, Reuters determined. Tailoring the propaganda campaign to local audiences across Central Asia and the Middle East, the Pentagon used a combination of fake social media accounts on multiple platforms to spread fear of China’s vaccines among Muslims at a time when the virus was killing tens of thousands of people each day. A key part of the strategy: amplify the disputed contention that, because vaccines sometimes contain pork gelatin, China’s shots could be considered forbidden under Islamic law. The military program started under former President Donald Trump and continued months into Joe Biden’s presidency, Reuters found – even after alarmed social media executives warned the new administration that the Pentagon had been trafficking in COVID misinformation. The Biden White House issued an edict in spring 2021 banning the anti-vax effort, which also disparaged vaccines produced by other rivals, and the Pentagon initiated an internal review, Reuters found.

The U.S. military is prohibited from targeting Americans with propaganda, and Reuters found no evidence the Pentagon’s influence operation did so. Spokespeople for Trump and Biden did not respond to requests for comment about the clandestine program. A senior Defense Department official acknowledged the U.S. military engaged in secret propaganda to disparage China’s vaccine in the developing world, but the official declined to provide details. A Pentagon spokeswoman said the U.S. military “uses a variety of platforms, including social media, to counter those malign influence attacks aimed at the U.S., allies, and partners.” She also noted that China had started a “disinformation campaign to falsely blame the United States for the spread of COVID-19.”

[...] The effort to stoke fear about Chinese inoculations risked undermining overall public trust in government health initiatives, including U.S.-made vaccines that became available later, Lucey and others said. Although the Chinese vaccines were found to be less effective than the American-led shots by Pfizer and Moderna, all were approved by the World Health Organization. Sinovac did not respond to a Reuters request for comment. Academic research published recently has shown that, when individuals develop skepticism toward a single vaccine, those doubts often lead to uncertainty about other inoculations. Lucey and other health experts say they saw such a scenario play out in Pakistan, where the Central Intelligence Agency used a fake hepatitis vaccination program in Abbottabad as cover to hunt for Osama bin Laden, the terrorist mastermind behind the attacks of September 11, 2001. Discovery of the ruse led to a backlash against an unrelated polio vaccination campaign, including attacks on healthcare workers, contributing to the reemergence of the deadly disease in the country.

[...] By summer 2020, the military’s propaganda campaign moved into new territory and darker messaging, ultimately drawing the attention of social media executives. In regions beyond Southeast Asia, senior officers in the U.S. Central Command, which oversees military operations across the Middle East and Central Asia, launched their own version of the COVID psyop, three former military officials told Reuters.

Although the Chinese vaccines were still months from release, controversy roiled the Muslim world over whether the vaccines contained pork gelatin and could be considered “haram,” or forbidden under Islamic law. Sinovac has said that the vaccine was “manufactured free of porcine materials.” Many Islamic religious authorities maintained that even if the vaccines did contain pork gelatin, they were still permissible since the treatments were being used to save human life. The Pentagon campaign sought to intensify fears about injecting a pig derivative. As part of an internal investigation at X, the social media company used IP addresses and browser data to identify more than 150 phony accounts that were operated from Tampa by U.S. Central Command and its contractors, according to an internal X document reviewed by Reuters. “Can you trust China, which tries to hide that its vaccine contains pork gelatin and distributes it in Central Asia and other Muslim countries where many people consider such a drug haram?” read an April 2021 tweet sent from a military-controlled account identified by X.

The Pentagon also covertly spread its messages on Facebook and Instagram, alarming executives at parent company Meta who had long been tracking the military accounts, according to former military officials. One military-created meme targeting Central Asia showed a pig made out of syringes, according to two people who viewed the image. Reuters found similar posts that traced back to U.S. Central Command. One shows a Chinese flag as a curtain separating Muslim women in hijabs and pigs stuck with vaccine syringes. In the center is a man with syringes; on his back is the word “China.” It targeted Central Asia, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, a country that distributed tens of millions of doses of China’s vaccines and participated in human trials. Translated into English, the X post reads: “China distributes a vaccine made of pork gelatin.”

Reuters reports that The Pentagon launched an anti-vaxx campaign in the Philippines and Central Asia to foment anti-Chinese sentiments against their Sinovac vaccine.

#The Pentagon#China#Sinophobia#Sinovac#Coronavirus Vaccines#Vaccines#Vaccine Hesitancy#Coronavirus#Philippines#Donald Trump#Joe Biden#Biden Administration#Trump Administration#Central Asia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Home PCR Tests: A Closer Look at the PCR Test At Home Dubai Option

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked major growth in the development and usage of diagnostic and antibody tests that patients can self-administer from home. Home PCR tests in particular enable private, convenient detection of active coronavirus infections. For those wondering whether accurate PCR Test At Home Dubai kits are available, exploring the leading options provides helpful guidance.

How Do Home PCR Tests for COVID-19 Work?

The PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technique is the gold standard for directly detecting the presence of the COVID-19 virus from respiratory samples. Home PCR test kits allow patients to collect their own nasal or saliva samples and perform the PCR assay without visiting a clinic.

PCR tests work by identifying the specific genetic material of the COVID-19 virus. Users collect a sample, mix it with chemical reagents, and insert the solution into the test kit for analysis. Results are displayed indicating whether viral genetic material was detected based on any color change reaction on the test strips.

Kits include step-by-step instructions to ensure patients perform the easy, quick tests properly using non-invasive nasal swabs or saliva collection. Many provide results within 10-30 minutes.

Here is a video from MedCram Youtube Channel about At Home Rapid COVID 19 Tests and False Positives (Coronavirus Antigen Tests). Watch the video

youtube

Benefits of At-Home PCR Testing

Here are some of the major advantages of having access to accurate home PCR tests for COVID-19:

Convenience: Test from the privacy of your residence without traveling to clinics.

Speed: Get results rapidly within minutes rather than waiting days for lab tests.

Self-Administered: Users can collect their own sample comfortably rather than relying on technicians.

Affordability: Individual kits are very competitively priced.

Detection Reliability: PCR technology directly identifies viral presence with high accuracy.

Ease of Use: Tests have simple, straightforward instructions for patients of all ages.

Infection Verification: Confirms active infections unlike antibody tests.

Having the option to privately, quickly, and accurately test for possible COVID-19 infections at home provides significant peace of mind during the pandemic.

How Reliable Are Home PCR Tests?

Many people reasonably wonder whether DIY home PCR test kits can match the reliability of lab-based PCR tests. The good news is that leading home PCR kits on the market have very high accuracy.

Most kits have published sensitivity and specificity above 90% when compared to lab PCR tests. High quality home tests analyze samples using comparable PCR methodology and match labs in detecting positives and negatives.

Furthermore, unlike Rapid PCR Test At Home kits some vendors offer, full home PCR tests analyze the sample through many amplification cycles to maximize accuracy. With good sampling collection, top home PCR kits offer laboratory-grade results conveniently at home.

Leading Home PCR Test Kit Options

For those exploring PCR Test At Home Dubai choices, here are some of the top-rated home PCR kits to consider:

Cue Health PCR Test: Cue offers an FDA-authorized home PCR test delivering highly accurate results in 20 minutes with nasal swab samples.

Lucira Check It PCR Test: This is a single-use PCR kit with 98% validated accuracy that provides molecular-level detection from nasal samples in 30 minutes or less.

Ellume COVID-19 Home Test: This over-the-counter home kit uses a mid-turbinate nasal sample and provides an amplified PCR digital reading of positive or negative in 15 minutes on a connected analyzer.

Pixel by LabCorp PCR Test: Pixel is a monitored at-home nasal PCR test analyzed through LabCorp with over 98% accuracy returning results within 1-2 days.

Doximity's Covid-19 PCR Test: Doximity partners with qualified labs for monitored video-observed PCR testing with 97%+ accuracy and results in 24 hours.

All these options allow for convenient, accurate at-home COVID-19 testing using PCR with trusted partners. Kits can be purchased online and shipped directly to your home in Dubai.

When Are Home PCR Tests Recommended?

The CDC recommends utilizing home PCR tests in situations such as:

If you have any symptoms of COVID-19. Home testing allows quick confirmation.

After exposure events to quickly check for possible infection.

Before visiting individuals at higher risk for severe illness.

Before travel or group events for added assurance.

For frequent screening in schools or workplaces.

Even fully vaccinated individuals should test if they experience COVID-like symptoms or have a known exposure. Home PCR tests make quick detection fast and easy.

Home PCR Tests Offer Accuracy and Convenience

High quality Home PCR Tests have become an important tool in the fight against COVID by making reliable diagnostic testing accessible outside of clinics. There are excellent PCR Test At Home Dubai options available matching the standards of lab PCR sensitivity and specificity. Home PCR kits allow people to conveniently and confidently check themselves for possible COVID-19 infections from the privacy of home. As the technology continues advancing, home collection PCR will likely take on an increasingly vital role supporting public health and safety.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plan For Garden Sheds with Porch

At the point when I was a kid, a property holder had built a brilliant little lodge for his children. We promptly made this our clubhouse and meeting place for every open air experience. This one-room lodge estimated Plans for Garden Shed with yard You might have heard the expressions "she shed" or "man space," yet property holders who fabricate extra living or working space through a cutting edge shed say they have become more useful and appreciate

Shed Plans 12X16 Free | Shed with patio, Lawn sheds, Shed homes

Quite a long time back, I was a little fellow, directly in the center of the time of increased birth rates made by fighters and mariners getting back from The Second Great War. Besides, it assists new organizations with performing a positive evaluation of their field-tested strategies since it covers a scope of themes market members should know about to stay cutthroat. Garden Shed When Leo Babler was brought into the world with an uncommon and dangerous hereditary problem, his folks reshaped their lives, moving to the mountains, working out an undertaking van, and ensuring their child encountered the

Shed Building Made Simple | Shed with patio, Yard plans, Shed plans

A Lanarkshire parliamentarian has upheld aggressive designs to further develop the which incorporate a polytunnel and garden region. "Maybe in particular, The Shed Base is an inviting social climate The space put away for the Learning Garden comprises of a walkway associating the library parking area to the walkway on the primary block of South West Road.

14x14 and 12x12 Wood Shed Kit | Little Garden Preparing Shed | House

Center around the shed base Especially assuming the water level ascents in the garden, you need to ensure that the base of your shed is completely safeguarded. One method for doing this is by adding a sealant between Jan 11, 2023 The Express wire - - Last Report will add the investigation of the effect of Russia-Ukraine War and Coronavirus on this Garden Sheds industry.

0 notes

Text

How could the United States of America have possibly let its enemies/China have near total control over the manufacture and production of its pharmaceuticals?

How could that possibly happen?

It has literally let people who disdain America and Americans have control over the vast majority of Americans’ life-saving medications. Who thought that was a good idea?

If the honest answer is “no one,” than how the hell did it happen?!

Would we have let Japan supply us with all of our armaments in World War II? Insanity!

The Trump administration has a great deal of work to do. The border, economy, forever wars, inflation, national debt, Deep State, crime … and pharmaceutical security, among other problems, such as undoing all the damage the Biden administration visited on America. It is a nearly unfathomable task, especially with Democrats opposing Trump every step of the way, though early returns look promising.

National security — no, national survival — is at stake.

China, accidentally or not, unleashed the coronavirus on the world -- with the help of Dr. Anthony Fauci and his federal agency -- leading to the subsequent Pandemic of Idiocy and Tyranny. That virtually all the facial masks and testing kits available during that time were made in China is indefensible. That China claimed it produced roughly half of all COVID-19 vaccines available globally is a crime.

This is, figuratively at least, bad medicine. And a bitter pill to swallow.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Listing the Well-Known Canine Parvovirus (CPV) Diagnostic Brands

Canine Parvovirus (CPV) is a highly contagious disease that poses a significant threat to dogs, and early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving the survival rate of dogs. There are various CPV diagnostic products on the market, let's take a look at some of the well-known brands.

IDEXX

IDEXX is a global leader in pet health, offering a range of diagnostic solutions from veterinary clinics to laboratories. IDEXX's CPV diagnostic products are known for their high accuracy and ease of use.

Zoetis

Zoetis is one of the largest animal health companies in the world, and its CPV diagnostic products are also highly reliable. Zoetis offers a wide range of products, including diagnostic reagents for various other pet diseases in addition to CPV testing.

Tashikin

Tashikin provides a rapid detection kit for canine parvovirus antigen (colloidal gold method), which is used to detect CPV antigens in dog feces, rectum, vomit, and saliva, suitable for screening and auxiliary diagnosis of CPV infection in dogs.

Heska

Heska's pet diagnostic product line is also very rich, and its CPV diagnostic kit is easy to operate with accurate results.

Virbac

Virbac is a global animal health care company, and its CPV diagnostic products also enjoy a high reputation in the market.

MEDIAN Diagnostics

MEDIAN Diagnostics' VDRG® CPV/CCV/Giardia Ag Rapid kit can detect canine parvovirus, coronavirus, and Giardia at the same time.

Other Brands

In addition to the above brands, many other brands on the market provide CPV diagnostic products, such as BioRad, Thermo Fisher Scientific, etc.

Considerations for Choosing CPV Diagnostic Products

Accuracy: This is the most important factor in choosing diagnostic products. Products that are certified and have high accuracy should be selected.

Ease of Use: For homes or small clinics, products that are easy to operate are more popular.

Test Items: In addition to CPV, some products can also detect other diseases at the same time, such as distemper, coronavirus, etc.

Price: Price is also a factor to consider, but low prices should not be pursued at the expense of the accuracy of the test results.

Warm Reminder:

Home diagnostic products are for reference only: These products can only provide preliminary diagnostic information. If your pet shows abnormal symptoms, take it to a veterinary hospital for a comprehensive examination promptly

Follow the instructions strictly: The usage methods of different products vary, so be sure to read the instructions carefully to avoid misoperation.

Regular maintenance of equipment: Equipment that requires calibration should be calibrated regularly to ensure the accuracy of the test results.

The spread of canine parvovirus can be effectively controlled through timely diagnosis and treatment, protecting more dogs to grow up healthily.

Are you curious to learn more about pet diagnostics? Follow me for in-depth explanations in my upcoming posts!

0 notes

Text

0 notes