#cm intertextuality

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Penelope Garcia & Spencer Reid // anonymous

Criminal Minds S2E11 (“Sex, Birth, Death”), S16E1 (“Just Getting Started”), S7E11 (“True Genius”), S15E10 (“And in the End”)

#Spencer Reid#Penelope Garcia#spenelope#criminal minds#cm intertextuality#Spencer Reid & Penelope Garcia#true genius#just getting started#and in the end#made for my best friend on her birthday#happy birthday my friend

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Price: [price_with_discount] (as of [price_update_date] - Details) [ad_1] Nyman's rise to international prominence during the last three decades has made him one of the world's most successful living composers. His music has nevertheless been criticized for its parasitic borrowing of other composers' ideas and for its relentless self-borrowing. In this first book-length study in English, Pwyll ap Siôn places Nyman's writings within the general context of Anglo-American experimentalism, minimalism and post-minimalism, and provides a series of useful contexts from which controversial aspects of Nyman's musical language can be more clearly understood and appreciated. Drawing upon terms informed by intertextual theory in general, appropriation and borrowing are first introduced within the context of twentieth-century art music and theory. Intertextual concepts are explained and their terms defined before Nyman's musical language is considered in relation to a series of intertextual classifications and types. These types then form the basis of a more in-depth study of his works during the second half of the book, ranging from opera and chamber music to film. Rather than restricting style and technique, Nyman's intertextual approach, on the contrary, is shown to provide his music with an almost infinite amount of variety, flexibility and diversity, and this has been used to illustrate a wide range of technical, aesthetic and expressive forms. He composes with his ear towards the past as if it were a rich quarry to mine, working like a musical archaeologist, uncovering artefacts and chiselling fresh and vibrant sonic edifices out of them. Publisher : Routledge; 1st edition (28 August 2007) Language : English Hardcover : 256 pages ISBN-10 : 1859282105 ISBN-13 : 978-1859282106 Item Weight : 522 g Dimensions : 15.88 x 2.54 x 23.5 cm Country of Origin : India [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

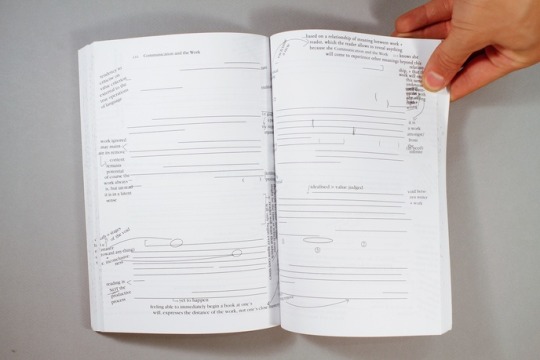

The book, a living object! - part 1

There are times where you suddenly encounter a work you wished to know about sooner as it gives new perspectives on subjects you love. That's what happened to me last Friday in our art history class told by Miss Joly. She was finishing her class on the different topologies of artists books and was presenting to us the section around “books about books.” Those works play with the typical features of books and question their limits. The piece that especially stood out to me was Reading The Remove Of Literature created in 2006 by Nick Thurston. This book is a republication of the english translation of the essay L’Espace littéraire written by Maurice Blanchot in 1955. Except, only the notes taken by the artist, Nick Thurston, are present. Thus, the space of the actual essay is visible in negative thanks to Thurston commentary going around it, in the margins and between paragraphs. This technique highlights the absence of the original text and its own weight as well as the power of the intertextuality created by the notes offered by the space of the book’s margins. Indeed, it is the specificity of the margin and the bond they allow that I want to explore here.

Pages from Reading The Reading Of Literature by Nick Thurston in 2006, 288 p, 23 x 15.5 cm, Paperback, Offset Printed in black and white, 1000 ex, ISBN 0955309212.

More than a mere convention, a book's margins hold multiple uses. The form of the book and the way it is made shape the page and use margins as a protective device. It is especially true in the case of gutter margins because of the space concealed by the bound and the unreachable paper near the crease. Outer margins protect the text from being damaged as well, to avoid that any content gets cut in the formatting of the book.

Apparently (I could not find very reliable sources for this fact, but it seemed credible enough to mention it) in the Medieval Ages, the reason books had such big outer margins was to prevent the damage rats could do. They would chew and tear pages, so margins were here to be sacrificed to their teeth and keep safe the precious text so tediously written by scribes.

Another component which explains the use of book margins is the ergonomic design of the book. Margins help to increase focus of the reader onto the content as it separates that same content from the outside world where the reader is. By being a “blank” space, the eye is less tempted to wander outside of the book. Outer and foot margins are also designed to welcome the reader’s hand and by such are often bigger than the head and gutter margins for an optimal grip without hiding anything.

Nonetheless, protection is not the only job margins have. They also are a place within the page to expand the book’s experience itself. Indeed, if margins are wide enough, they can be written on by the reader and welcome thoughts and ideas. The content of the book becomes one part of a physical dialogue with the reader. As such, many stories and narratives are linear with a constant rhythm dictated by a book’s pages. The margins can help one disrupt this flow by giving him the chance to include his own temporality within its reading. Those notes essentially are working like anchors whether it holds emotional, creative or study purposes while giving an active participation to the book for its reader.

Furthermore, I would like to explore this concept through transtextuality given by books as a medium. Transtextuality has multiple definitions as it is a relatively newer way of studying books and literature. Here I got mainly interested by Gérad Genette’s definition theorized in his essay Palimpsestes — La littérature au second degré published in 1982. Genette defines transtextuality as everything which puts a text through to another text. This hypothesis is very interesting as it gives a new way to see stories. Instead of being a single entity, it clearly affirms the book and its content as part of a greater system. Like a rhizome that grows with each new added work and evolves consequently. Newer work can give new light, thanks to transtextuality, to previous work as much as newer work got enriched by what was already part of literature. Within transtextuality, Genette proceeds to characterize, different yet non-exclusive, types of connection that link texts to each other. The one that grabbed my attention is the metatextuality: The way one text is bound to another one as it is its commentary. We could say that notes written on margins are thus part of that metatextual relation. Our first example, Reading The Remove Of Literature is symptomatic of this and plays with this very concept. It is a clever way to highlight this phenomenon as well as inviting and sharing this personal experience of the book that Thurston got to experience.

This article is getting quite lengthy, so I will continue to explore those ideas in another blog post. Yet to finish this one, I would like to add a short conclusion. Margins are, as a bookworm and aspiring editorial designer, a wonderful object of research. They are a way for the book to give the reader a unique connection. The reader takes hold of the book, gets directly involved and becomes a part of the rhizomatic system that keeps the book as a living, evolving and always re-activated medium!

Next time, I want to deepen those ideas and try to see how far we can stretch this bond through the special case of ergodic literature and transmediality with the example of the novel S. by Doug Dorst and JJ. Abrams.

4370 signs

0 notes

Text

Examining Layers of Meaning in Rebellious Silence.

This is my essay on meaning for critical studies. I chose this artist for her photographic images that raised many questions for me when I first came across her work. I love the layering of script on photograph, the staged manner of her compositions. They are so clearly staged that it calls for further interrogation...what is she trying to convey and why?

Examining Layers of Meaning in Rebellious Silence

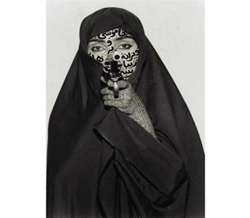

Rebellious Silence, 1994, Shirin Neshat.

Ink on LE silver gelatin print, (131.8 x 92.7 x 4.8 cm).

Introduction

In this essay I will examine how meaning is made and translated in an image by Shirin Neshat titled Rebellious Silence, part of the Women of Allah series. I intend to evaluate and analyse the image employing Roland Barthes theories of semiotics and intertextuality.

Theory and Framework

Barthes was one of the leading theorists of semiotics which is the study of signs. In this context, a sign refers to something which conveys meaning – a written or spoken word, a symbol or a myth (Robinson, 2011). Semiotics is concerned with anything that can stand for something else, it is an interpretation of everything around us. According to Barthes’ theory, every ideological sign is either Denotative (literal) or Connotative (Roland Barthes and his semiotic theory, 2018). In the dictionary Connotation is an idea or feeling which a word invokes in addition to its literal or primary meaning. Signs have both a signifier, being the physical form of the sign as we perceive it through our senses and the signified or meaning that is interpreted (Roland Barthes and his semiotic theory, 2018). Neshat’s work is dense with powerful imagery and I will use this to consider the meanings of various signs within the image.

Intertextuality is the shaping of a text's (or image) meaning by another text, in this case I am concerned with the interconnection between the related works of the series of pictures Women of Allah and how the interpretation of the individual image is affected by placing it within the series. I will use this theory to reflect upon how my interpretation of the work developed from a naive first reading, through to a more informed understanding based upon how the work related to Neshat’s wider practice.

Artwork and Author

Rebellious Silence is a staged black and white photograph of a woman dressed in Chador, which is a full body cloak held closed at the neck (A Brief History of the Veil in Islam, 2020). Her hair, head and shoulders are covered but her face is not. The photograph has had Farsi text added to the woman’s face by Neshat post-production. The woman is holding a rifle, her hands are not included in the image’s composition but from the way her arms are held beneath the Chador one would suppose she is holding the butt of the rifle securely in both hands. The barrel of the rifle perfectly bisects her face and the image vertically. It appears as if her chin and nose are touching the barrel and her eyes stare at the viewer from either side. Her eyes are defined using a black, Kohl eyeliner. Behind the figure is a horizontal line and would form a cross with the gun barrel were the figure not obscuring the line.

Neshat, an Iranian, was absent from her homeland during and after the Iranian Islamic Revolution for a period of about 12 years. The Iran she found upon her return was very different to the secular Persian culture she had grown up in and had left behind in 1975, aged just 17. She was able to visit again in the early 1990’s finding a country that was now under theocratic Islamic rule and very changed. She produced this series between 1993 and 1997 because she felt compelled to make art that reflected what she had experienced in Iran and to find a way to frame her own questions regarding the foundation of the Islamic Revolution and especially how it had impacted the lives of Iranian women (Neshat,2019, pg.75).

Evaluation and analysis.

Initial Reading

Personally, I encountered much confusion and nervousness when I first came across this image, but found the image so visually arresting that I was encouraged to investigate rather than move on. On my first reading, I assumed that it had been made as a comment on the terrorist attacks of 9/11. However, I later discovered that it was produced in 1994, seven years before the World Trade Centre attacks. My experience of the image changed as I increased my knowledge of its context and the authors intended meaning, and upon reflection I can see that my initial reaction to her work was the result of cultural ideologies formed from a Westerner’s viewpoint.

Symbolism, Sign and Signified

The woman is centralised, her figure is bisected by a gun barrel, creating an image of two halves. The shape of the gun, held in such a way, seems evocative of praying hands in the Christian tradition. Although it’s unlikely that Neshat intended this reading of the work, given her Muslim background, I can’t escape the way that my own Christian background informs this interpretation. In his essay “The Death of The Author” (1976), Barthes asserts that we need not ask ourselves what the author intended in the creation of his or her work but how the viewer reads or interprets it, he focuses on the interaction of the audience, not the maker, with it. This means that the text is much more open to interpretation, much more fluid in its meaning than previously thought (Short summary: Death of the Author - Roland Barthes, 2017). I don’t adhere entirely to his ideas on this, I believe the intended reading is as valid as my own and that it will be just one of many interpretations.

Dr. Allison Young remarks in her essay that “The woman's eyes stare intensely towards the viewer from both sides of this divide”, (Young, 2015). To me, this visual divide reads as a potent signifier of the opposing cultures Shirin Neshat has experienced and her negotiation of the chasm that separates them. The one she was born to and which has, since her leaving Iran, intensified into a Theocracy (by way of a revolution) and the one she has been adopted into, in the USA. She has found herself an alien in both circumstances although arguably belonging to both, one by birth and the other by residence and choice. In Iran, she is considered as subversive and provocative, her work has offended the caliphate and she is banned from visiting, whereas in the USA, she has had to contend with prejudice and outright hostility, especially during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979, during which time American sentiments were distinctly Anti-Iranian (Neshat, 2019, p.16). The ideologies of both cultures are opposed, anti-Muslim stereotypes prevail in The West, marking Muslim women who wear the veil as a symbol of religious fundamentalism and extremism. Neshat is confronting the overriding discourse on the part of the West towards the East. She provocatively employs the Remington rifle to split the face, she sees and experiences both sides.

The gun in the photograph is a particularly powerful image. It has connotations of power, death and destruction. I find it uncomfortable and it raises many questions. Is she hiding behind its power, is she manipulated by the weapon or is she the manipulator? Is the carrying of this weapon her choice? Does she represent the power and aggressor or the defender of her culture or ideology? Or is it a comment on the power of the Theocracy? Women were called to arms during the Iran/Iraq war in the 1980’s and this was hailed by the government as being progressive and liberating for women, whilst paradoxically mandating them to observe religious piety in the wearing of the veil; their freedoms, sexuality, expression and movement are physically restricted.

Intertextuality

This photograph was taken during the second tranche (there were 3) of the Women of Allah series, the Farsi writing we see layered upon the photograph here is by the Iranian female poet, Tahereh Saffarzadeh. Farsi is the Persian word for the Persian language. Farsi and Arabic are not the same. So are the woman or women in these pictures identified or identifying as Persian, with connotations of the previous more socially permissive rule of the Shahs, rather than Iranian? Persia, as a culture, is rich in symbolism. Conversely the poem deals with the issues of martyrdom which became popular and was encouraged by the new Iranian Government during the revolution. The audience majority in the West will find that the Farsi writing covering the face is unintelligible, incomprehensible. To a Westerm audience, who the work was arguably made for, the meaning is hidden in plain sight. The text that we are unable to comprehend is reduced to decoration under our gaze. The script also serves to complete the veil figuratively, in that her face is further disguised from sight. It is a complex relationship that Iranian women have with issues such as Martyrdom, cultural identity and the wearing of the veil. Each interrogation of the image simply provides me with more questions as the layers are examined. Neshat says in a conversation with Glenn Lowry that she approaches her subjects as a sociologist would, framing the issues but never providing any answers. (Neshat, 2019, pg.75).

One should not overlook the relevance the Women of Allah series has today, post 9/11, even though the series is almost 25 years old. It has most recently been exhibited at the Broad in Los Angeles, as part of a retrospective exhibition of Shirin Neshat’s work. Neshat’s intended reading is changed by the context the work is displayed in, and by the events that happen in the intervening years given the current global events relating to fundamentalist terror attacks this century. An audience’s reading is inevitably different now than it would have been when the work was made adding another set of layers of interpretation. Are we able to make the distinction between Persian, Iranian or ‘Arab’? Can we view these images without reference to suicide bombings carried out by veiled women? I think not, which speaks to its relevance in today’s society. Recently exhibited alongside her films and more recent of works, the exhibition as a whole adds to your experience of the singular, I imagine the breadth of subject matter, the multi-media nature of her work and the monochrome nature of the offerings speak to an intensely personal experience.

The veil has come to be understood as either a symbol of Muslim women’s oppression or their resistance, constructed as dichotomous perspectives (Ladhani, 2019). In a free, liberal Western society, the veil is often read as the subjugation of women and a mechanism of control. There are many Muslim women who take exception to that perception, finding a freedom beneath the veil, free from the critical and sexual male gaze. Part of the provocation of these images is to question our ideological affinity to this discourse. The veil worn in its various forms (leaving out Christian traditions around the marriage ceremony) ‘by women appears with such constancy that it generally suffices to characterize Arab society’ (A Brief History of the Veil in Islam, 2020). In this picture we see an Arab, Muslim woman, holding a gun and staring at the viewer, it shifts the subjugated female to a politically motivated weapon, there is an undercurrent of violence and politics. The eyes seem to penetrate, and her face is adorned by incomprehensible text. I was initially nervous of this image, she seemed completely ‘other’ to me. I questioned whether it was a challenge to faith or ideology or was it a propaganda image? The way the gun is positioned is reminiscent of holding a finger to your lips in the internationally recognised sign or command for quiet, silence. Is she silenced by the gun or does the reference to the gun create the silence by fear? By intertextually using other images that speak to one another in a series she is able to more fully explore the symbolic nature of the gun. They inform one another. The weapon is conceivably passive in Rebellious Silence, whereas if you view another in the series, Faceless

FACELESS, 1994. (Shirin Neshat, MutualArt, 2020)

the subject is actively holding the gun with the viewer in its sights, her finger on the trigger and hand covered in Farsi text which is extolling the beauty of Martyrdom. The meaning of the text is still hidden from us, that in itself promotes a degree of fear, we are excluded from understanding it.

Both the gun and the poem give the woman a voice whilst cloaked in a silencing and constricting Chador.

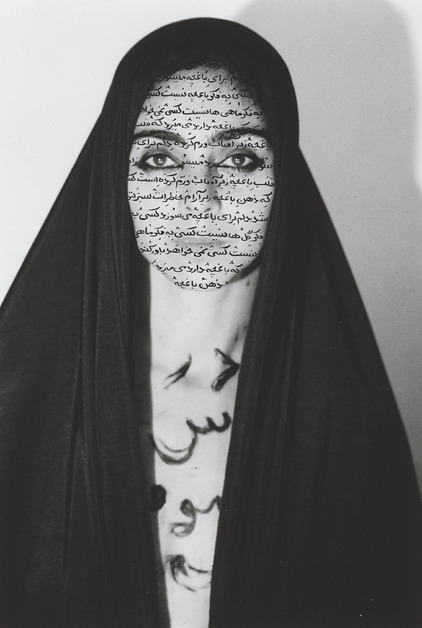

Unveiling,1993, is one of her earlier photographs but still part of the same series, Neshat is pictured in the photograph and has written the poetry of Farrokhzad over her face. The words of this poem deal with the struggle women find in navigating the strict religious, social codes whilst recognising their sexual desires. It is a love poem, the author’s works are banned in Iran, whilst Tahereh Saffarzadeh writings about Martyrdom are applauded.

Unveiling (Christies.com, Shirin Neshat, 2012)

Here she appears naked beneath her Chador, it is a seductive and sensual image and the poetry, if we could but understand it gives voice to her desires. These images and the others belonging to the same series give a duality of message. Speaking to the differing circumstances and roles women inhabit in contemporary Iran and prodding the Wests perceptions and judgements. It is no one thing, this issue of Women of Allah, it is varied and complex and difficult to grasp and articulate. Sheliza Ladhani says in her essay Decentering the Veil, that contemporary discourse surrounding Muslim women who veil continues to be about them as opposed to from them (Ladhani, 2019). Within Iran, and amongst Iranian women are women who want to express themselves and their desires as well as those who adhere whole heartedly to the religious dictates. Neshat delivers both these women and others to our notice in her series. She also explores her feelings of separateness and exile from her home, family and culture. Ed Schad says in ‘I will Greet the Sun Again’, the catalogue that was produced for the exhibition at The Broad, that Neshat’s photos are beautiful articulations of empathy and identification, saturated in a visual language learned in New York and applied to an examination of contemporary Iran. These photos echo the voices of women whose freedom balances precariously on the fault line of an Iran caught between modernizing and conservative forces (Neshat, 2019, pg15).

Conclusion

Neshat recalls that her first exhibition of the Women of Allah series was written about by a New York Times critic. He had complained about her work as being too confusing, wondering where she was coming from. He asked was it a case of radical chic or a way to romanticise violence? (Neshat, 2019, pg. 76). He may have a point. The inclusion of the gun in some of her works in this series is provoking and shocking, it is a tool of destruction and violence. When seen in reference to an Islamic veil and in the hands of a woman our minds travel to radicalisation and fundamentalism. But there is an irony and conflict here too, given the US’s much debated and firmly held right to bear arms. Neshat as a naturalised American has the right to bear arms, but as a Muslim, she could be said to be one of the reasons that the US want to bear arms – for protection. The inclusion of the rifle could be speaking to this dichotomy.

As we have seen Rebellious Silence is a deeply layered and challenging work, but its impact lies in its ambiguity, complexity and difficulty. By confronting the viewer with a dense set of signs and symbols, Neshat forces us to think more deeply and to question her intentions. Nothing can be taken for granted and nothing is made easy. It’s through this challenge that the photograph and wider series Women of Allah prompts debate and discussion, which is ultimately how change and awareness come about. The photographs openly wear paradoxes and what seem like contradictory points of view, says Ed Schad (Neshat, 2019, pg. 15). In agreeing or disagreeing with the artists intended meaning and debating its efficacy, we bring ourselves into the experience and thus have a unique reaction and viewpoint from which to decipher the work. Perhaps it is because of these many layers of meaning that the work is still so relevant today.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Febrero 16, 2020

Little Women, al pie de la letra

Una de las preguntas que aparecen no bien acabada de ver Little Women, quizá la que más curiosidad despierte, es la de la clase de vínculo que entablan con ella quienes no pueden recurrir a su intertextualidad específica, quienes llegan a la sala (o presionan play) sin conocer la historia, la novela, ni ninguna de las películas anteriores.

La Little Women de Greta Gerwig tiene, por lo menos, dos rasgos salientes que la distancian de sus predecesoras. Por un lado, como ha dicho Filipe Furtado en su reseña de la película, Gerwig hace de la novela más una referencia textual que el objeto de una trasposición dramática, lo que convierte a la película en una obra, hasta cierto punto, más radical de lo que podría esperarse. Esta inclinación hacia lo textual es particularmente evidente en al menos dos planos -que recuerde- en los que una vez Josephine March y otra Friedrich Bhaer dicen sus monólogos mirando directo a la cámara. Pero, más allá de esos momentos, el dispositivo textual está presente en toda la película. Se trata, acota Furtado (en traducción mía), “de una serie de anotaciones a la novela de Alcott que son a la vez amorosas, pero conscientes de su punto de vista (aunque de una manera ahistórica, muy 2019)”. Por otra parte, agrega que la narrativa de Little Women no resulta realmente conmovedora, salvo en algunos pasajes individuales que se destacan por sí mismos – no coincido con la probable identificación de esos pasajes, y aun menos con la valoración de que ellos sean “grandes momentos”, pero no es necesario entrar en esta cuestión, por ahora.

La segunda característica notoria y peculiar de la película de Gerwig es su estructura narrativa hecha de entretejidos temporales. No se trata, como se intuiría al comienzo, de que estemos viendo la historia desde un presente que recurre de modo insistente a flashbacks disparados quizá por la memoria de una Jo March ya más crecida que se gana la vida como profesora en Nueva York. Tampoco, de la mera alternancia de flashbacks y flashforwards, que podrían ser anticipaciones de la Jo March narradora. La estructura de Little Women es algo más ingeniosa o, si prefieren, más inteligente. A poco de avanzado el relato nos damos cuenta de que las estampas de la historia de las chicas March se van entretejiendo, sin que haya propiamente un punto de anclaje que podamos identificar de modo inequívoco como el presente de la narradora. Se establece un contrapunto sincrónico, según el que cada escena remite a otra equivalente (una cuestión pendiente sería ver en qué consisten esas equivalencias, o cómo se dan) situada en algún otro momento del arco temporal que abarca la historia. Estas escenas seleccionadas, entresacadas, de la novela y de las películas anteriores son siempre muy emblemáticas, son aquellas que es prácticamente imposible que quienes hayamos tenido algún contacto con Mujercitas de pequeños no guardemos casi como fetiches cinéfilos, literarios y aun de la propia infancia.

Contrariamente a lo que podría pensarse, sin embargo, creo que Furtado acierta cuando dice que la película carece de intensidad dramática. Gerwig despojó a la historia de Louisa May Alcott no solo de su espesor epocal, de todo lo que hacía que la comprensión de los personajes se diera en relación con ese medio –lo que no es necesariamente un defecto, ni un problema; de hecho, encuentro estimulante que Gerwig vacíe un poco de pasado, y de su propio pasado en la tradición, a la película, para traerla al presente, también, como otra cosa –, sino que además - y esto sí lo encuentro problemático-, es como si el guion confiara demasiado en el poder referencial y evocativo de esas escenas y se relevara, por lo tanto, de darles un valor propio. Como cuando estamos con un amigo que conocemos desde hace mucho tiempo y algo que pasa cerca de nosotros trae un recuerdo que se sabe tan compartido y tan entrañable que nos basta con decir “¿te acordás de aquel día cuando...?” y con eso ya los dos nos reímos, o nos conmovemos, sin que haga falta añadir nada más. Solo que aquí esa familiaridad no basta. Todo pasa de modo un poco apresurado, sin que las secuencias cobren el vuelo, ni el cuerpo suficientes para que lleguen a emocionarnos. La sensación es que los planos, a veces con aspiraciones fordianas, se amontonan un poco sin ton ni son, en un montaje, como ellos mismos, desprovisto de gracia y que resulta cada vez más arbitrario y desalentador.

La reconfiguración -para usar la misma expresión de Furtado- de Friedrich Bhaer -para más inri, con el aun relativamente joven y sin discusión bello Louis Garrel a cargo del personaje- sea quizá una de las peores decisiones. Sus consecuencias se hacen sentir, en especial, en la escena final que Bhaer protagoniza con Jo y que no alcanza ni de lejos las cotas dramáticas que ese momento condensaba en la novela – y estamos hablando de una escena que sí se quiere dramática, no puramente virada a su referencia textual o intertextual. Algo parecido pasa en las escenas de Jo y Laurie, con Ronan y Chalamet haciendo monerías tomados de la mano, de ser posible, contra un prado bonito de fondo porque eso es el amor prístino e inconsciente de sí de la juventud; o incluso cuando discuten ya de modo más amargo. No sé cómo tomarán estas escenas, y otras, quienes nunca vieron las versiones anteriores, ni leyeron la novela; pero nos resulta muy difícil creer en ellas. O quizá, se trata de una sensibilidad, la de Gerwig, con la que no consigo acoplar. De hecho, mientras miraba la película pensaba “qué feo es esto que estoy viendo; qué feo lo que escucho, qué feo”.

Pero siempre nos queda la inteligencia de la estructura. A medida que la película avanza, la velocidad del entretejido se acelera y ahora creo que, más bien, esa estructura debe parangonarse con la figura de un acordeón cuyo fuelle en repliegue acerca y confunde cada vez más lo que tenemos por pasado, por presente y por futuro. Ese recurso es el que hace posible una vuelta de tuerca y una sorpresa final: ahora es una Jo March pretérita la que al escribir su novela, y por la necesidad de complacer la exigencia de su editor, cambia el final de la historia para posibilitar el happy ending demandado, en una suerte de volver al futuro, con notas de feminismo. Hay que reconocerlo: el ingenio tiene su miga. Aun así, el ánimo era más bien sombrío a la salida del cine. Y no porque esta Mujercitas nos haya puesto de frente, sin escapatoria, ante el espectáculo de la caída de las ilusiones del amor romántico, del matrimonio, o del final feliz. Más probablemente, porque nos puso ante una ficción débil y desdibujada. Algo, en fin, que de ninguna manera estábamos dispuestas a aceptar.

cm

Little Women, Greta Gerwig (2019)

135 min, EE.UU, inglés

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOTES ON 'MADE OF WHAT'

THE CONCEPT

After finding an article on Tollund Man, a famous bog body from Denmark, I wanted to know if there were any mummified corpses found in Estonian swamps. I quickly came across the Rabivere Woman discovered in 1936 and estimated to be around 350 years old.

The articles about the body mention their gender and social status, keeping an air of mystery that often surround such findings and lost histories. Having previously imagined Helgi Saldo as a gender-queer figure emerging from the wild to be at odds with the contemporary world, the Rabivere Woman was the perfect starting point for the project — my first try at creating a concept album.

The idea to create music for Helgi started off as a joke. From Conchita Wurst to Trixie Mattel to Divine, drag performers making (often awful or uninspired) music seemed like a trope that would be fun to play with. I invited Mikk Madisson to help me write, compose and produce the EP, planning three songs in different decades, also known as "songs that never made it to Eurovision".

Rabiveres on levinud kaks rahvajuttu. Neist üks on klassikalise motiivistikuga lugu neiust, keda tabas õnnetu armastus ning kes sooritas enesetapu ja maeti sohu. Teine lugu jutustab kõrtsielu armastanud naisest, kes liiga sageli üle raba kõrtsis käis, kuni jäi ühel ööl kadunuks.

THE LUSTWORT

When curator Keiu Krikmann asked me to be a part of the exhibition, I was adamant that my usual drag practice belongs to clubs and queer spaces, not established galleries. I wanted to rather queer the gallery space itself, becoming a part of it in ways I usually wouldn't be.

The idea was to create a room-wide, queerspreading installation which would double as a costume for the performance, as well as a space for the visitors to listen to the music outside the performance.

Omal ajal rabalaipa uurinud teadlased kirjeldavad, et tegemist oli 25–32-aastase naisega, kes oli 155–160 cm pikk. Naise riided olid rohmakalt parandatud ja mitmeid kordi paigatud. Pealmise kuue esiosa tugev kulumine viitab, et naine tegi selles füüsilist tööd. Rõivaste väljanägemist tervikuna hinnates oli tema sotsiaalne staatus madal.

Tallinn-based Sorcerer was my first choice, as they are a brand who challenges ideas of beauty, gender and modes of production. They are also a collective rather than a single artist, with their scraps-to-art aesthetic ironically befitting different accounts and descriptions of the Rabivere bog body.

We came up with the idea of using a hammock as the centerpiece, where people could sit and listen to the songs. The carnivorous sundews — also known as lustwort — was one of the visual inspirations. We effectively created sort of a pea pod with guts and an umbilical cord hanging out, which gave the whole thing a much needed body horror aspect.

THE SONGS

Estonian queer histories aren't widely known or documented, and I wondered what it would sound like to insert Helgi Saldo into the history of (Estonian) pop music. However, the project evolved to be something more than an exercise in style, something more contemporary, intertextual and weird. Through anachronisms and sounds, the queer stepped to the forefront, past was reframed rather than regurgitated.

The first piece "Briquette Bardot" was inspired by the 1960s, with the central figure of Briquette being both a bog body as well as a metaphor for mining swamps for fuel. Inspiration was drawn from different songs of the time, especially from the lyricist Heldur Karmo.

a flame sly in her heart, her face a queer illusion if she could, she’d escape her bittersweet seclusion!

The second song "Work" was meant to be inspired by the 1990s and an anthem for the club kid. What started as a riff on Sin With Sebastian ("Shut up and sleep with me" became "I don't want to work"), eventually included anachronisms like references to social media and Britney Spears, which speak more to the present day. The lyrics for the Estonian translation "Töölaul" were more directly inspired by Onu Bella whose debut album was released in 1992.

ma ei taha teha tööd luban, paus saab kandev ma ei taha teha tööd puhka jalga, anton hansen

The third song was supposed to be an exploration of something more contemporary, but it only materialised later in the process and did not make it to the exhibition itself. Instead, I wrote an interlude between the first two songs called "Club Toilet" which was a compilation of phrases I'd heard working or partying in different clubs.

Eventually I arrived at "Summer of MPX", in which the lyrics center queer histories and how the gay community has been at the butt end of different pandemics. And while a song like Latour's "People Are Still Having Sex" could be considered somewhat timeless, "MPX" in its title at least anchors it in a very specific moment in time.

i’m queer to stand and lay at the conference of stags in eden and its shade with mighty branded fags

* If I was to plan a whole album with this concept, I would fill in the gaps from 70s, 80s, '00s — but in all honesty it would be a lot more interesting if some other self-appointed queer archeologist would do that, creating a cross-generational project that would add new layers to the existing ideas, and voices other than my own.

Tallinn, September 2022

ADDENDUM

November, 2022 I spoke too soon. There were other two decades I decided to cover: the 70s with Seenesõber and 80s with Tundmatu. The 1976 song was inspired by an article I found on drug use in the Soviet Union. It mentioned LGBT people and artists and dancers as most likely users, and — this might be urban legend — that in some cases people used shoe polish to get high. The lyrics in the first part reference the fact homosexuality was criminalised and cruising was done in secret. The structure of the song was inspired by Hando Runnel and RUJA's "Keldrikakand".

seenesõber pargis käis nägi baleriini mustikal

The 80s saw the rise of Glasnost in the Soviet Union, paving way to a new national awakening and the Singing Revolution. For these lyrics, I wanted to create a nationalist sequel to Briquette — an empowering ballad for a breakup with the regime. The original version ended up a very fittingly cringe retelling of a figure who made a deal with the devil, brought darkness to the singer's life and eventually made her stronger for it.

It's also a song about transitioning, with the singer claiming "the man has grown into a woman". This particular line was inspired by an article from an Estonian trans woman who mentioned coming out to her wife in the late 1980s.

Üle taeva laotan ma leegi, mul on jõudu rohkem kui eile. Mind peatada ei saa keegi, sest mehest on sirgunud naine.

To bring it all together, I included the name of the album into the chorus, along with references to Briquette, the cult film Nukitsamees and another Heldur Karmo song about the colour of love.

This concludes the Soviet decades, with a Eurovision song planned for the 2000s.

0 notes

Text

Han Kang, “Human Acts” (translated by Deborah Smith)

S4E17, Demonology // S12E7, Mirror Image // S2E5, Aftermath // S10E11, The Forever People

#Emily Prentiss#Tara Lewis#Elle Greenaway#Jennifer Jareau#criminal minds#cmedits#bau#bau team#cm women#cm intertextuality#cm screencaps#quote

382 notes

·

View notes

Photo

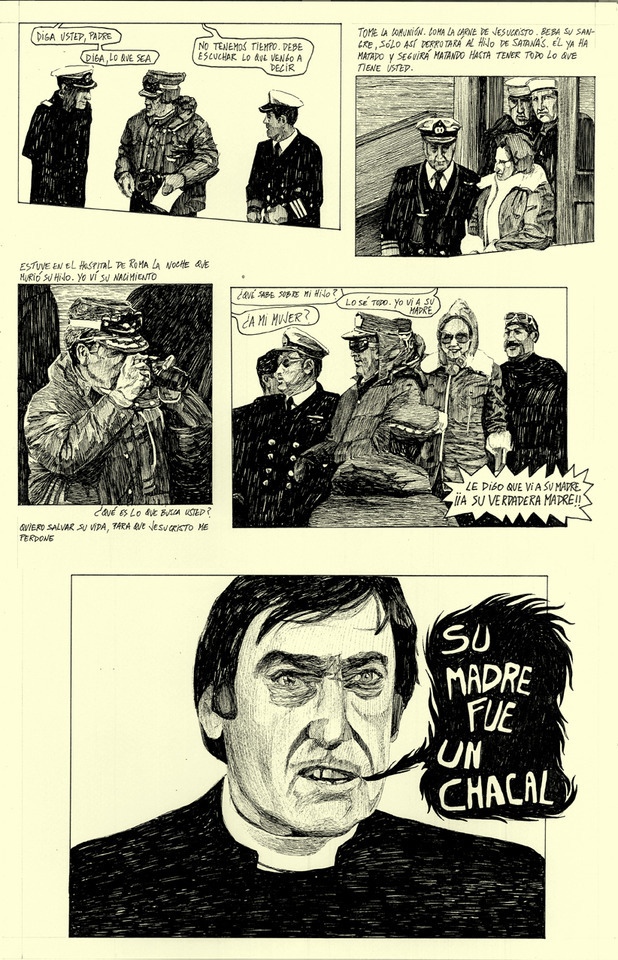

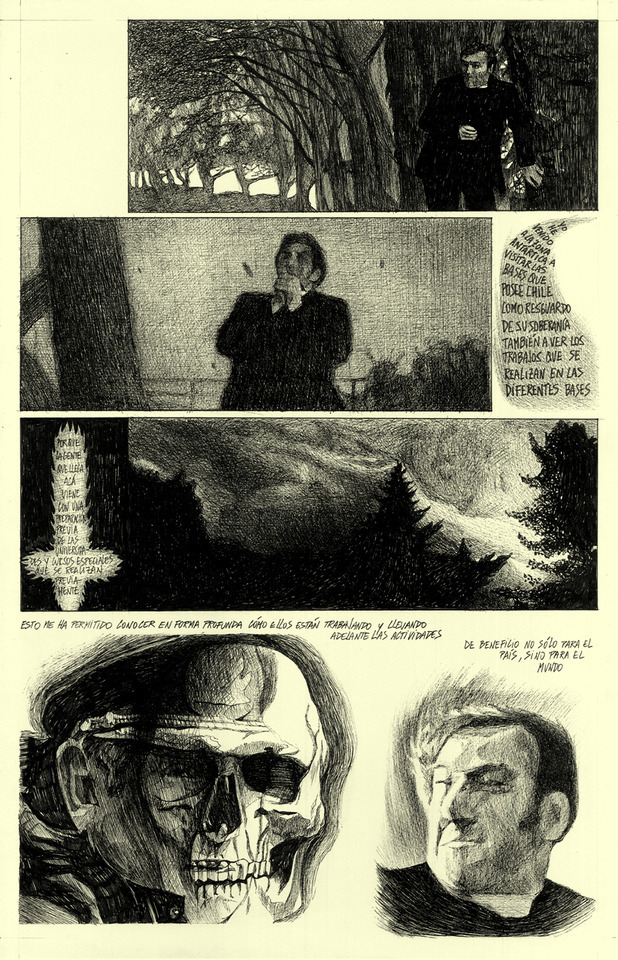

Javier Rodríguez Pino ( CL)

-

666

Dibujo

Lápiz tinta sobre papel

5 láminas de 45 x 29 cm.

2014.

-

La línea de investigación que, dentro del área de la práctica artística, he desarrollado en los últimos 4 años, consiste en hacer un cruce, desde el dibujo, el realismo fotográfico y las ciencias sociales, entre dos tipos de imágenes: las del “mal” y la de los medios de comunicación. Esta relación ha desarrollado una especie de pop ácido u oscuro que intenta producir inquietud e incertidumbre frente a los relatos y sentidos que se desprenden de las imágenes televisivas, cinematográficas, publicitarias y de prensa. Concretamente, dicha problemática, la he trabajado desde los escenarios de violencia política ocurridos en Chile durante los últimos 45 años, principalmente, a partir de lo que he denominado como “documentales gráficos” ya que desde entrevistas, fotos de archivo y reportajes, como también, desde el cómic y una tradición de la grafica política heredada del grabado, dejan testimonio de figuras que tanto la historia como los medios de comunicación no han sabido recoger en toda su complejidad, criminalizándolos, la mayoría de las veces tras la imagen de lo malvado. Bajo este marco, destaco, “Malos” (2014), que indaga en el fenómeno de los jóvenes encapuchados en Chile, “Fantasma” (“2014), el cual se concentra en la historia del desaparecido grupo subversivo chileno “Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez” y su relación con el fracaso, y “Revólver” (2016), propuesta intertextual entre dos sucesos del año 1965 que invitaban a pensar una posibilidad de mundo distinto, me refiero al lanzamiento del disco Revólver de “The Beatles” y al surgimiento del MIR chileno

Para este ciclo de exposiciones en Galería Cordillera, presento 666, una serie de dibujos del año 2014 que consiste en 5 láminas de 45 x 29 cm., las que a partir del realismo fotográfico, cruzan dos piezas audiovisuales –ambas del año 1976– que encierran un siniestro misterio: la primera de ellas es un documental español que registra el primer viaje de Pinochet a la Antártica, mientras que la segunda es la conocida cinta de terror sobre el hijo del diablo, “La profecía”.

-

+: www.javierodriguezpino.com

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Price: [price_with_discount] (as of [price_update_date] - Details) [ad_1] Nyman's rise to international prominence during the last three decades has made him one of the world's most successful living composers. His music has nevertheless been criticized for its parasitic borrowing of other composers' ideas and for its relentless self-borrowing. In this first book-length study in English, Pwyll ap Siôn places Nyman's writings within the general context of Anglo-American experimentalism, minimalism and post-minimalism, and provides a series of useful contexts from which controversial aspects of Nyman's musical language can be more clearly understood and appreciated. Drawing upon terms informed by intertextual theory in general, appropriation and borrowing are first introduced within the context of twentieth-century art music and theory. Intertextual concepts are explained and their terms defined before Nyman's musical language is considered in relation to a series of intertextual classifications and types. These types then form the basis of a more in-depth study of his works during the second half of the book, ranging from opera and chamber music to film. Rather than restricting style and technique, Nyman's intertextual approach, on the contrary, is shown to provide his music with an almost infinite amount of variety, flexibility and diversity, and this has been used to illustrate a wide range of technical, aesthetic and expressive forms. He composes with his ear towards the past as if it were a rich quarry to mine, working like a musical archaeologist, uncovering artefacts and chiselling fresh and vibrant sonic edifices out of them. Publisher : Routledge; 1st edition (28 August 2007) Language : English Hardcover : 256 pages ISBN-10 : 1859282105 ISBN-13 : 978-1859282106 Item Weight : 522 g Dimensions : 15.88 x 2.54 x 23.5 cm Country of Origin : India [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

MITCHELL MESSINA’S TUTORIAL HOMEWORK:

Ciao Bella (2001) by Tracey Rose

Tracey Rose is a South African artist whose practice centers on installation, video, photography and performance. Rose deals with themes of gender, race, identity politics and history which are mostly interpreted through the use of her own body. Like the American artist Cindy Sherman, Rose places herself within the narrative to create multiple layers of meanings. Through this she also explore her own identity politics as a person of colour in South Africa by inserting herself into her own reinterpretations of western art and history. Eurocentric history objectifies and exoticises non-western bodies, especially female, and so by inserting herself into these spaces Rose is bringing her own sense of awareness.

Ciao Bella is a video installation work which Rose presented for the 2001 Venice Biennale. The work entails a series of photographs and a triple-screen video projection which all depict a parodic recreation of the infamous painting The Last Supper (1495–1498) by Leonardo Da Vinci. Rose plays the role of twelve female caricatures who embody archetypes of objectified female beauty such as Marie Antionette and Saartjie Baartman. By referencing The Last Super, Rose intends for this work to interrogate how religious beliefs have constructed the roles of “male” and “female” in society. Her practice investigates histories of violence, especially violence against womxn and their unvoiced presence in history. This is made evident in Ciao Bella as the thirteen-minute work depicts a chaotic narrative in which Rose’s twelve characters appear stuck in their individual repetitive lives. The video seems to break this rhythm with the first spoken words which are quoted from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. The words make reference to the famous saying, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” This alludes to the objectification of womxn and the notion of the male gaze. By inserting herself into these characters Rose creates another layer of critique as she makes them become relevant to her time and location in space. We see the work in context to our own history and knowledge. A foreigner viewing the work at the Venice Biennale in 2001 will interpret it differently to a South African in 2019.

The abstract, fantasy-like elements of the work reminds me of Dystopian or Utopian qualities of a postcolonial South Africa. In this colourful scene, there is tension between these characters who come from different histories and backgrounds and they play off of each other. Rose’s Marie Antionette idly cuts cake while another character portraying “Cicciolina”, a famous porn star (who has worked with Jeff Koons) confidently splays out on the table. Ciao Bella is drenched in intertextual references and the variety of archetypes suggests several lifetimes of oppression.

In relation to Ciao Bella, Rose’s Marie Antionette makes an appearance in another one of her photographic works titled MAQEII (2002). In this composition she is seen standing in front a RDP settlement with a cake in her hand, which could be a reference to wealth gaps and social inequality in South Africa.

Tracey Rose

Ciao Bella, 2001

Dan Gunn

Rear projection colour triptych with stereo audio speakers

The Last Supper

Leonardo Da Vinci

(1495–1498)

Tempera, Gesso

460 cm × 880 cm

MAQEII

2002

Lambda photograph

118.5 × 118.5 cm

Edition of 6

0 notes

Text

HOMEWORK TASK FOR CHRIS'S TUTORIAL

#christut1

1. ICTAF makes a positive contribution to Cape Town’s upper middle class attendees, and creates an approachable entrance for art novices. For many people who would not make a habit out of visiting galleries, the Art Fair is a great way to immerse oneself in local and international work. As laymen and art collectors navigate the space alongside each other, it is an entry point into the art world, which can be intimidating and inaccessible for an outsider. It also gives artists an opportunity to display their work to a much larger audience than they might have at a gallery show. It provides a holistic and varied view of contemporary South African art, boasting an easy buffet of artists and galleries.

2. Though the ICTAF has a positive effect for Cape Town’s upper middle class – as described above – the hefty entrance fee makes it inaccessible for a majority of South Africans. Though the CTICC is an accessible venue for public transport, located near to a taxi rank, train station and myCiti bus stop, it is not an accessible or welcoming environment for everybody. The CTICC is technically a “public” space, but with security guards located all over the building it is only people of a certain socio-economic status who constitute that “public”. It may also have a negative impact on the perceptions of the clientele who do attend the fair, as the exclusive and prestigious environment with it’s overpriced restaurant and Boschendal wine sponsorship may perpetuate a perception that art production belongs to and is mediated exclusively by the rich and educated.

The crowded booth layout would be difficult to negotiate for someone with mobility issues. With English the only language at the fair, it firmly locates the contemporary South African art world as an exclusively English medium space, despite the fact that a number – if not a majority – of contemporary South African artists speak English as a second or third language. It also limits the clientele to people proficient in English.

3.

Tabita Rezaire

INNER FIRE: BBHMM, 2016

Disc print

170 x 100 cm

Rezaire’s solo exhibition at the Art Fair explores an imagined world saturated with diverse references from a myriad of sources from both the global North and South. Mixing influences from innumerable sources, including pop star FKA Twigs, Internet meme culture, millennial kitsch, Nike, vaporwave, selfie portraiture, neo-liberal consumerism and an 80s sci-fi aesthetic, Rezaire demonstrates the tidal wave of influence and iteration in our globalised world. This is focused particularly on Internet culture, which is at the forefront of the millennial era of globalization, centered less on nation conquering and more on conceptual and referential spread. Over the Internet, linguistic conventions, fashion, news, information and ideas are almost instantly spread across the globe. With a majority of Internet content originating from the Global North, South African web culture is unequivocally influenced by and immersed in our global social world, dominated by the developed world. Rather than simplifying and restricting her commentary to the simple moralistic binary of good and bad (can globalisation be declared good or bad?), Rezaire holds a mirror up to the digital landscape, capturing a collage of intertextual references, images and ideas.

No picture available.

A simple white vase with a single pink flower is depicted next to a chair, against a pale blue backdrop.

Marsi van de Heuvel

Subjective feelings, 2018

Fineliner on Fabriano

29 x 21

Coming from a complete novice perspective this critique might be utterly misplaced and somewhat harsh, but van de Heuvel’s work strikes me as representative of a trend with some white contemporary South African artists who’s privilege allows them the luxury of producing apathetic, apolitical art. Though not obviously related to globalization, her work rings of an old European tradition of art making as a gentile pastime . Not to bash everyone who paints still lives, but van de Heuvel seems to produce work in a vacume, as though removed from the context in which she is working. This still life seems static and outdated against the backdrop of the dynamic globalised world. While Rezaire’s work is saturated with conversation with the context in which she is working, van de Heuvel depicts a subject matter dislocated from her temporal and political context. Describing her other work van de Heuvel comments “flowers are consolations” (from the Smith website). This seems like a very flow response to the world that she is living and creating in, where a more rigorous response than consolation seems appropriate. Working in 2018, van de Heuvel’s work seems devoid of conversation or connection with the world around her. This jars in our globalised context, saturated with influence in a digital world where conversation is both unavoidable and unrelenting.

0 notes

Photo

90s rewatch project: Love and a .45 (1994, Talkington)

Filed Under: Love on the Run

Verdict: In the 90s, there was an inherent subgenre of small, independent films attempting to copy those “bigger” independents. On its surface, <i>Love and a .45</i> seems to fall into that category. In fact, the original incarnation of this review was framed in that manner. Until I did a little research and discovered claims of this so-called copycatting being accused as the other way around. But we’ll get into that more later.

Love and a .45 is a movie that is self-aware in certain aspects while holding back in others. Its ultimate downfall isn’t necessarily the suggested lack of originality or the clunky acting and pacing, but the fact that it doesn’t commit <i>enough</i>. Our leading female, played by Renee Zellweger, is your standard of the “lovers on the run” trope: southern, simplistic, and beautiful. Her leading man, Gil Bellows, is boorish, anxiety-riddled, and greasy. Star (Zellweger) likens the couple’s recent murder spree to that of “the movies,” specifically citing Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty as Bonnie and Clyde. Watty (Bellows) tells her, flatly, that everyone in those movies get caught or killed. They have this conversation while it appears that director CM Talkington is mimicking the jerky, dreamlike car conversations in Natural Born Killers.

However, according to an interview with Talkington from 2015, Oliver Stone stole from him and not the reverse. He goes into a story in an interview which seems a little too convoluted and detailed to be a lie, but who truly knows. Talkington has said this obvious assumption that he was the imitator has hurt. Perhaps he’s right and my initial reaction upon rewatch was merely another incorrect assumption of Talkington’s craft. But unfortunately that still doesn’t change the fact that the end result stills reads as a lackluster ode to more well-crafted movies. In another scene that is very tough to refute as not being a deliberate mirroring, a character dances around with a gun in a suit ala Michael Madsen in Reservoir Dogs. In a later scene, that same character is bleeding out in that same suit in the back of a car, ala Tim Roth in the same movie. Apparently, in 2009, Tarantino called Talkington his “favorite imitator.” Talkington has said he never imitated Tarantino because he was writing his drafts at the same time that Tarantino was writing his movies. This reasoning is a little tougher to swallow, considering Love and a .45 came out a few years after Reservoir Dogs, and not only were these scenes left in the movie, but they’re also instantly recognizable.

Love and a .45 was released in 1994, at the height of the ultra-violent genre that was prevalent in indie Hollywood at the time, with the likes of such early 90s releases as Reservoir Dogs, Killing Zoe, True Romance, Natural Born Killers, and Pulp Fiction. Every filmmaker wanted to be the next Tarantino or Oliver Stone. That much is evident by Talkington, who’d never directed a feature film before, using “a film by” title card in the opening credits. It reeks of pretentiousness and copycat cinema, when pretension and copycatting already existed (in a more masterfully auteur fashion) with Tarantino himself.

If Talkington had committed further, perhaps it would’ve felt less like rip-off (intentional or not) and more like self-aware intertextuality. If someone within the universe of Love and a .45 -- in which movies like Bonnie and Clyde exist -- had commented, “Hey, this feels like that scene in Reservoir Dogs, man,” the tone would’ve shifted to a point that might have worked marginally better. But instead, <i>Love and a .45</i> brings in a Misirlou-esque soundtrack in its final climax, and fails to allow its characters to exist in a world in which they are craving to being directed by Tarantino, but having to settle for a debut from a director that didn’t go as far as he should have in his commitment to the genre.

0 notes

Photo

Decisions from a place of lack with Adam Siekel by Eglė Norkutė

2017 150 x 130 cm Oil on canvas

ART AND COLLECTIBLES was inspired by The fictional gallery project U.F.O. Gallery — Gallery Ganek, initiated by Július Koller in 1971. The gallery’s high location at Malý Ganek — an almost three-hundred-meter mountain peak with a northwest wall that attracted climbers — symbolized the encounter between the earthly and the cosmic. For my own likewise fictional exhibition memorizing (most importantly — not forgetting) and collecting unique experiences play the main role. Bratislava castle was chosen as its location not only to consolidate this three-month stay in this city, but also as a way to emphasize projects absurd nature.

I see prospective memory as a paradox. „Remembering to remember“ is another way to describe this type of memory. Doomed to forget, we urge to remember. This state opens up paths to the possible emergence of a new organisation of reality – in a scope stretching from organising perception or sensuality to the organisation of reason and subjectivity. Lacking the sense of reality that is already buried in the past, collection starts filling up the walls of the blue hall. A sense of lack and deficiency are the main causes that shape this part of the exhibition. Aesthetic and emotional value overcome linear timeline, topographic structure fails as major mental images wrestle through time washing out fragile details.

Are we in a room that is meant to grant something, or are we in the middle of an unfurling disaster? The stories behind the displayed artifacts do not allow the viewer to understand the exhibition's design better, hereby proving its intertextual character. The viewer (in this case – colleague painter Adam Siekel) is rather objectified, nearly the opposite of spectator and practically has become one of the exhibits.

#artandcollectibles#painting#oil on canvas#oil painting#contemporarypainting#contemporaryart#eglenorkute

0 notes

Photo

Glenn Ligon Knows What Time It Is On Art Versed (March 2016)

Glenn Ligon has always had a preoccupation with the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality. Ligon’s two exhibitions What We Said The Last Time and We Need To Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is, in which the artist illustrates his engrossment with these subjects, are occurring simultaneously at Luhring Augustine‘s Chelsea and Bushwick locations.

What We Said The Last Time features a series of seventeen enlarged prints from the paint-splattered pages of the artist’s well-worn copy James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village” from Notes of a Native Son (published 1955). Written during a stay in a small settlement in Switzerland, “Stranger in the Village” examines race as a social construct. “From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came,” Baldwin writes as he documents his experiences as a gay black man visiting the small Swiss town as a way to better understand the African American identity. Also on view is Entanglements, a curatorial project by Ligon that examines how artists use the studio as a base from which to engage momentous cultural shifts and political events in both direct and oblique ways.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled, 2016, 71 x 49 inches (180.3 x 124.5 cm)

Beginning in 1996, Ligon has used Baldwin’s essay as the basis for his “Stranger” series, which includes prints, drawings, and paintings made from oil slick and occasionally coal dust that nearly obscures the text. While working on this series, Ligon kept copies of Baldwin’s essay on his studio table for reference, and over the years they accumulated a large amount of black paint, oil stains, and fingerprints. This show marks the first time Ligon has used the entirety of Baldwin’s essay in his career. Like so much of Ligon’s work, the resulting prints illustrate the role of intertextuality in contemporary art, and how one medium can simultaneously inform and contradict another. The use of Baldwin’s seminal essay attests to the power of language and ink on paper, but Ligon’s pseudo-redaction of the text tells us something different. One page has the page number and top right corner completely ripped off and thick drops of paint cover sections of the text, but we can still see his quick annotations, contrasting Baldwin’s ruminations with the artist’s own spontaneity.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled, 2016, 71 x 49 inches (180.3 x 124.5 cm)

We Need To Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is in Bushwick opened January 16 and predominantly features Ligon’s Live (2014), a silent video installation based on the 1982 film Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip. This is not the first time Mr. Ligon has engaged with Pryor’s work. The artist’s text-based paintings often incorporate references to Pryor’s stand-up, most notably in a series of gold-colored paintings beginning in 1993 based on Pryor’s groundbreaking material from the 1970s. The installation is set up in a circle of six large screens and a smaller screen in a corner. On the smaller screen, we see the unedited version of Pryor’s original performance, while the other screens zoom in on specific parts of Pryor’s body as they appear in the original footage: his head, his shadow, his right hand, his left hand, his mouth, and his groin. The projected images are visible from both sides of the screen, so the viewer can encircle the installation and almost always be confronted by Pryor’s captivating stage presence. Each screen is illuminated only when their designated body parts appear in the original film, so the screens sporadically flicker on and off as your eyes jump around the room to catch his image.

Installation view, We Need To Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is, Luhring Augustine Bushwick

Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip won the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Recording in 1982, and is still widely considered one of the best comedy albums of all time. Throughout his illustrious career and chaotic personal life, Pryor was anything but shy about his views on sexuality, social injustice, and drug use. On the night on June 9, 1980, for instance, Pryor notoriously lit himself on fire with nothing but a bottle of rum and a match after freebasing cocaine, an incident that undoubtedly accounts for his flame red suit and yellow boutonniere (he also begins his act by asking the members of the audience “Anybody got a light?”)

Installation view, We Need To Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is, Luhring Augustine Bushwick

By fragmenting the footage, Pryor’s body parts seems to move independently from the others. His rapid gestures seem second nature to him, but his expression shifts seamlessly between deadpan and animated throughout the film. The lack of audio is particularly jarring when we see Pryor erupt into fits of emotional gestures and cursing. These moments are often followed by brief periods of complete silence and darkness as the camera temporarily leaves the comedian’s body.

Installation view, We Need To Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is, Luhring Augustine Bushwick

Ligon, Pryor, and Baldwin all share an obsession with the idea of black masculinity, but by drawing on this idea rather than readily subverting it, all three were able to contrast the narrative of blackness with its reality. By cutting up Pryor’s image and muting his voice, and by blacking out Baldwin’s text, Ligon illuminates their vulnerability. This installation subtly critiques the social constructs of race and masculinity, but also emphasizes the limits of language in expressing ourselves to one another. The artist forces us to contemplate the ways in which we represent ourselves, both voluntarily and unconsciously. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, he also conveys the fact that to be marginalized either as a group or individually means to be silenced, or to essentially be rendered without language. If we do not have language, how do we communicate? Some say that actions speak louder than words, but it seems that Mr. Ligon does not believe the two should be separated.

What We Said The Last Time at Luhring Augustine in Chelsea is on view until April 2, 2016; We Need To Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is at Luhring Augustine Bushwick is on view until April 17, 2016.

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Many Shades of Glenn Ligon’s Blue Black

Installation shot of Glenn Ligon’s “A Small Band” (2015), neon and paint, 74 3/4 x 797 1/2 inches (189.86 x 2025.65 cm, with Ellsworth Kelly’s “Blue Black” (2000) in the background. (Ligon image courtesy of the artist; Thomas Dane Gallery, London; Luhring Augustine, New York; Regan Projects, Los Angeles, © Glenn Ligon, photo © Alise O’Brien Photography)

ST. LOUIS — In the entrance gallery of the Pulitzer Arts Foundation are a series of figurative painting, sculpture, and a photographic print all staring at each other. This scene of interiority opens the group exhibition Blue Black curated by the artist Glenn Ligon. Kerry James Marshall’s central character in “Untitled (policeman)” (2015), wearing his standard issue, navy blue Chicago Police Department uniform, hand on his hip, looks out in a moment of reflection, at the boy on the other wall in Carrie Mae Weems’ “Blue Black Boy” (1997), whose eyes gape. The peering of the boy represents an image born out of black cultural looking and the white historical gaze. The first is perceived if you focus on the officer’s eyes which make present the knowing glance of a black father at his son. The other image this looking relationship produces, in my mind, is what happens when the effects of the white gaze is recognized to be more than a theoretical construct but something representative of systemic power structures that have real life consequence. Under the white gaze, the black child becomes another black boy, like Michael Brown and the officer, representative of the history of law enforcement as an institution that polices black bodies unjustly, his race evaporates, he is simply an agent of the state, like the white patrolman, Darren Wilson. The looks that passed between Wilson and Brown brought about the final moments of Brown’s life because Wilson, per his testimony, saw the unarmed 18 year-old black boy as a “demon” in that suburban St. Louis street.

Carrie Mae Weems, “Blue Black Boy (1997), blue-toned print, 15 3/8 x 15 1/4 inches (39 x 38.7 cm) Framed: 31 1/8 x 31 1/8 x 1 7/16 inches (79.1 x 79.1 x 3.8 cm) (Collection Jack Shainman, New York, © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

If you walk into the frame of Weems’ photograph, which is to say the blue black boy’s line of vision, your presence is mirrored back — you are looking and looked at. If you don’t walk into his line of sight, he peers out at Jack Whitten’s abstracted version of himself in “Self Portrait I” (2014). The hang of all the mounted works is inspired by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibiting technique that places her black fictive figures within eyesight of each other. In this gallery, Ligon places Yiadom-Boakye’s “Messages from Elsewhere,” a 2013 oil of a black female figure wearing a lapis lazuli dress, gazing over her shoulder, lost in contemplation. She’s daydreaming in the direction of Whitten’s face. Sitting in the center of the room is Simone Leigh’s sightless femme terracotta statuette, “Dunham” (2017), sporting an afro. There’s something spiritual about the way she sees nothing, yet is seen by every figure in the room.

If the figures are looking, they must be thinking, searching, and seeing too. But what are they searching and seeing? Inside, the gallery, I didn’t wonder, I knew: the blue black experience.

Kerry James Marshall, “Untitled (policeman)” (2015), synthetic polymer paint on PVC panel with plexi frame, 60 x 60 inches (152.4 × 152.4 cm) (image courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mimi Haas in honor of Marie-Josée Kravis, 2016, Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY)

It’s not the general black, African-American journey. It’s a more limited and yet liberating voyage taken by and through skin so black, so dark, it coruscates blue. The men, women and child, exchanging what Ligon calls, “black looks,” are a reminder that there are various hues of the various black identities that coalesce into the African-American experience. “Blue-black is the kind of black where you go, ‘Black!,’” writes Ligon in his curatorial essay. He continues:

Perhaps that’s because blue-black traces its roots back to a mythic point of origin in Africa, whereas “black,” along with “Negro” and “African-American,” might be considered just one more stopping point on the way to an as-yet-unknown destination.

In a culture where the color of your skin is paramount, each color category — from the highest of yellows which can slip into an off-white of privilege, to the blues of black, which can make one feel like an Ellisonian disappearing act — comes with its own unique experiences of racism, colorism, freedom and death. Visually, racially, formally, metaphysically, each of the artists’ blue black representations appear together as you walk through the gallery, acclimating you to Ligon’s curatorial thinking about color and race.

Andy Warhol, “Liz #4” (1963), synthetic polymer paint silkscreened on canvas, 40 x 40 inches (101.6 x 101.6 cm) (images courtesy private collection, © 2017 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Born in the South Bronx in 1960, Ligon’s earliest grammar school memory is of words changing the trajectory of his life. “Words were the ticket,” he tells me, laughing. In kindergarten, Ligon’s teacher asked the class to write four letters of the alphabet and a word that starts with each letter. Five-year-old Ligon asked his teacher to write out the rest of the alphabet for him and he wrote words to match. The school’s administration called his mother, a nurse’s aide, into a meeting and said that he needed to go to a different kind of school. Ligon says while his mother was explaining that she didn’t have the money to send her young boys to private school, a teacher interjected, “Your kids might be smart here, but in a real school they will only be average.” “Ok, I’m going to find a real school for my kids to be average in,” said Ligon’s mother, “because in this school they’ve already been written off in kindergarten.” Ligon ended up at the tony Walden School and says, “that alphabet, those words, changed my life.” In the exhibition, Ligon’s pays sly homage to that 1965 moment by including his 2001 work, “Malcolm X, Sun, Frederick Douglass, Boy with Bubbles (version 2) #2,” a large-scale silkscreen of a page out of a 1960s Black Power-themed coloring book, representing a new kind of knowledge that awaited him.

Blue Black itself is an extension of Ligon’s fascination with language. The artist organizes the show less like a curator and more like a poet, arranging the work around three lyrical combinations of the words blue and black. One section meant to respond directly to an Ellsworth Kelly sculpture is titled, “blue black,” after the wall work that inspired the exhibition. The second, “blueblack,” features works that blur the lines between the two colors. The last, “blue-black” is partially inspired by Toni Morrison’s 1992 Guardian interview in which she articulates the heart of American identity: “In this country, American means white. Everybody else have to hyphenate.” The slippage of language inspired Ligon to utilize a poet’s ability to sublimely marshal simple words with debilitating force. The exhibition includes Ligon’s text painting, “Untitled (I Am Not Tragically Colored)” (1990). It’s a work in which the artist appropriates the line, “I am not tragically colored,” from Zora Neale Hurston’s celebrated 1928 essay, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” and stencils it in bluish-black oil repeatedly on a wooden door. With each impression, the phrase gets messier, less visible, and broken into pieces: “I am not,” and single words, “colored,” alluding to the intertextuality and mutability of language. The work “Untitled (I Am Not Tragically Colored)” is an overture to Ligon’s three-decades-long practice of using text, painting, installation and video to investigate the rhetorical power of the black voice.

Ellsworth Kelly’s “Blue Black” (2000), Painted aluminum panels 336 x 70 x 2 1/8 inches (photo courtesy Pulitzer Arts Foundation, photograph by Robert Pettus)

The idea for the group exhibition came to Ligon as he gazed up at Ellsworth Kelly’s monumental work “Blue Black” (2000), a 28-foot-tall painted wall sculpture commissioned for the Tadao Ando designed main exhibition hall of Pulitzer Arts. As he looked at the rectangular blocks of blue and black, he tells me he “heard Louis Armstrong’s gravel-strewn voice singing, ‘What did I do to be so black and blue?’” Given the title, other associations could have come to mind: the sound of Miles Davis’s trumpet on his 1959 modal jazz masterpiece, Kind of Blue; President Obama when he tried to convey to Ta-Nehisi Coates that his Kenyan father was certifiably black by exclaiming, “he was like a blue-black brother;” The popstar Rihanna, when she wails on her ballad, “Love on the Brain,” that love “beats me black and blue;” the queer black film, Moonlight adapted from Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play, In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue. For me, when I was growing up blue black wasn’t something you wanted to be. Light skinned black boys on the playground would tease darker children by saying, “You so black, you blue!” Nowhere in Ligon’s exhibition is the shadier descriptor — a black person’s fear of being too black! — explored. Nor is what happened after the teasing on the playground revealed: darker skinned students would lead inquisitions to determine if those of us who could easily win membership to any blue vein society were black enough. “To my friend who acts white, but you still my dog Antwizzy,” one friend wrote in my eighth grade yearbook. “Hope you never change. Love ya the way you are. Stay black/white ha ha ha.”

In contrast to my own experience, when it turns to matters of personhood, the art in the exhibition tends to show blue blackness as a source of pride, or pain inflicted not by colorism, but by white racism. The self taught artist, Bill Traylor’s cardboard painting, “Man and Woman” (c.1939–1924), for instance, depicts a white man in a blue skirt and a pitch-black woman in a blue shirt, exchanging glances. The painting is presented in the context of his life: He was born into slavery in rural Alabama in 1853. Similarly, Kara Walker’s large tempera and watercolor collage, “Four Idioms on Negro Art #1 Folk” (2015), is a scene of stereotype and systemic white racism. In the work on paper, black figures slide down stripper poles and hold their hands up, as military men aim rifles at their bodies. It’s as if they are saying “don’t shoot,” but the limbs scattered throughout the grounds suggest they are murdered anyway, socially and physically. Viviane Sassen’s “Kinee,” (2011), an abstracted image of the beautiful Senegalese model, Kinee Diouf, in a field of sky blue, feels aspirational, showing how blue-blackness has ascertained a certain desirability in fashion and life. (The inclusion of this Sassen image also brings to my mind, the fact that, blue-blackness as identity is a purely African-American invention. Africa’s history of colonialism has, country by country, created different measures of blackness.)

Simone Leigh’s “Dunham” (2017), terracotta, porcelain, raffia, steel, glass bead, epoxy, India ink, 35 x 30 x 30 inches (88.9 x 76.2 x 76.2 cm) (Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York, © Simone Leigh, Installation view of Blue Black, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 Photograph © Alise O’Brien Photography)

The work entitled, “A Small Band” (2015), is a zigzagging, large-scale blue neon sign comprised of three words: Blues, bruise, and blood. For the piece the artist appropriates a slice of the audio from composer Steve Reich’s Come Out (1966), that quotes Daniel Hamm, a young Harlem resident accused of murder and beaten by the police, describing to a court how he managed to convinced the cops to release him: “I had to open the bruise up and let some of the blues … bruise blood come out to show them.” On the stand, Hamm’s tongue gets tied and, like an unwitting poet, he turns three simple words into new meaning, revealing a truth about black pain and how black musicians sang the blues so convincingly. Standing before the Ligon text sculpture, flashing blue in the main gallery, it was impossible for me not to think of other short lyrical phrases packing the power of racialized color. “Black Is Beautiful,” “Black Lives Matter,” “I Can’t Breathe,” all made under duress in times of black struggle.

Given Ligon’s extreme care in organizing a diverse and conceptually challenging exhibition featuring some nearly sixty works by artists including Wade Guyton, Byron Kim, Lyle Ashton Harris, and ones already mentioned, I wondered during my visit whether the museum’s policy of not including wall text with the works will help or hinder his effort to have color considered beyond race. There’s a real possibility, save for the lone iconic Warhol of Liz Taylor, that the audience without information in captions, will assume that Blue Black is of work by black artists toiling solely in matters of race, instead of a show of the colors and metaphorical meanings of blue and black as ways to challenge simple categorizations of race and art.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, “Messages from Elsewhere” (2013), oil on canvas, 59 x 55 inches (149.9 x 139.7 cm) (Private Collection, Chicago © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, image courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Corvi-Mora, London)

Installation view of Blue Black, West Gallery, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 (Photograph © Alise O’Brien Photography)

Installation view of Blue Black with a work by Ligon on the left, West Gallery, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 (Photograph © Alise O’Brien Photography)

Norman Lewis, “Blue and Boogie” (1974), oil on canvas 44 1/4 x 56 inches (112.4 x 142.24 cm), Framed: 46 x 58 x 2 1/2 inches (116.8 x 147 x 6.4 cm) (courtesy The Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of the Estate of Norman Lewis 1981.1.1, photo: Marc Bernier)

Installation view of a Yoruba sculpture and a work by Ed Adkins at Blue Black, West Gallery, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 (Photograph by Jim Corbett © Alise O’Brien Photography)

Tim Rollins and K.O.S., “Invisible Man (after Ralph Ellison)” (2015), Indigo and matte acrylic on book pages on panel, 36 x 36 inches (91.4 x 91.4 cm) (Courtesy Studio K.O.S., Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong, Courtesy Studio K.O.S., Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong, photo: Christopher Burke Studios, LLC)

Installation view with works by Chris Ofili and Philip Guston in Blue Black, West Gallery, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 (Photograph © Alise O’Brien Photography)

Overall installation view of Blue Black, West Gallery, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 (Photograph © Alise O’Brien Photography)

Derek Jarman, “Blue” (1993), digitized 35 mm film (Courtesy of Basilisk Communications/Zeitgeist © Basilisk Communications Ltd, installation view of Blue Black, South Gallery, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 Photograph by Jim Corbett © Alise O’Brien Photography)

Installation view of Blue Black with works by David Hammons and Ed Mack, West Gallery, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2017 (Photograph © Alise O’Brien Photography)