#can move pretty efficiently and in some more serious situations might move the bare minimum (to surprise you later with his speed)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why so many people type 'lol' with a straight face: An investigation

There's a deceitful act I've been engaging in for years—lol—but it wasn't until recently, while texting a massive rant to a friend, that I became aware of just how bad it is.

I'd just sent an exhaustive recap of my nightmarish day when a mysteriously placed "lol" caught my eye. Not a single part of me had felt like laughing when I typed the message, yet I'd ended my massive paragraph with the words, "I'm so stressed lol."

I had zero recollection of typing the three letters, but there they were, just chilling at the end of my thought in place of a punctuation mark. I hadn't found anything funny, so why were they there? Unclear! I scrolled through my conversations and noticed "lol" at the end of nearly every message I’d sent — funny or not. That's when I realized how frequently and insincerely I use the initialism in messages. I was on auto-lol.

SEE ALSO: Crush Twitter proves that sometimes subtweets can be good

The next day, I arrived to work with a heightened sense of lol awareness and took note of my colleagues' behavior on Slack. They too, overused "lol" in conversation. Chrissy Teigen tweeted about the family hamster again? "Lol." Someone's selling a jean diaper? "Lol." Steve Buscemi's name autocorrected to Steph Buscemi? "Lol."

It was ubiquitous. And though some made audible chuckles at their desks throughout the day, the newsroom remained relatively silent. People were not laughing out loud whenever they said they were. It was all a sham!

As I'm sure is true with everyone, there are times when I'll type "lol" and smile, chuckle, or genuinely laugh out loud. But I'm also notoriously capable of assembling the three letters without moving a facial muscle.

Curious to know why so many of us insist on typing "lol" when we aren't laughing, I turned to some experts.

Why so serious? Lol.

Lisa Davidson, Chair of NYU's Department of Linguistics, specializes in phonetics, but she's also a self-proclaimed "prolific user" of "lol" in texts. When I approached Davidson in hopes of uncovering why the acronym comes out of people like laugh vomit, she helpfully offered to analyze her own messaging patterns.

On its surface, Davidson suspects "the written and sound structure" of "lol" is pleasing, and the symmetry of how it's typed or said likely adds to that appeal. The 'l' and 'o' are also right next to each other on a keyboard, she notes, which makes for "a very efficient acronym." In taking a deeper look, however, she recognized several other reasons one might overdo it with the initialism.

Davidson often sees "lol" used in conjunction with self-deprecating humor, or to poke fun at someone in a bad situation, like "if someone says they're stuck on the subway, and you text back 'lol, have fun with that.'" And in certain cases, she notes, "lol" can be included "to play down aggressiveness, especially if used in conjunction with something that might come across as critical or demanding."

"For example, if you're working on a project with a co-worker, and they save a file to the wrong place in a shared Drive, you [might] say something like, 'Hey, you put that file in the Presentations folder, lol. Next time can you save it to Drafts?'"

Extremely relatable.

Admitting we have a problem

After hearing from Davidson, I set out to analyze a few of my own text messages. I found several of her interpretations applicable and even discovered a few specific to my personal texting habits.

When telling my friend about my stressful day, for instance, I realized I'd included the lol that anchored my message for comfort, like a nervous giggle. In my mind, it meant I was keeping things light, which must mean everything's OK. In many cases, I also add "lol" to a message to make it sound less abrasive. Without it, I fear a message comes across as cold or incomplete.

On occasion, I'll send single "lol" texts to acknowledge I've received a message, but have nothing else to add to the conversation. And as much as it pains me to admit, the lol is sometimes there as a result of laziness. I experience moments of pure emotional exhaustion in which I'd rather opt for a short and sweet response than fully articulate my thoughts. In those cases, "lol" almost always delivers.

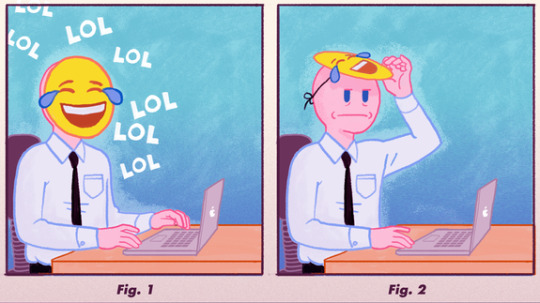

A poor soul removing his "lol" mask after a long day of pretending to laugh.

Image: bob al-greene / mashable

The realization that "lol" has become a sort of a conversational crutch for me is somewhat disturbing, but I can take a shred of solace knowing I'm not alone. As previously noted, many of my colleagues are also on auto-lol. (If you need some proof, 3,662 results popped up when I searched the term in Mashable Slack, and those are just the lols visible to me.)

When I brought up the topic of lol addiction in the office, offenders quickly came forward in an attempt to explain their personal behavior. Some said they use it as a buffer word to fill awkward silences, while others revealed they consider it a kinder alternative to the dreaded "k."

Several people admitted they call upon "lol" in times when they feel like being sarcastic or passive aggressive, whereas others use it to avoid confrontation, claiming it "lessens the blow of what we say."

"I've also noticed a lot with my friends that if they say something that creates a sense of vulnerability they'll use 'lol' or 'haha' to diminish its importance," another colleague noted.

While there are a slew of deeper meanings behind "lol," sometimes the lack of audible laughter simply comes down to self-control. You can use the term to communicate you genuinely think something's funny, but you might not be in a physical position to laugh about it — kind of how people type "I'M SCREAMING" and do not scream.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by ❝ randy ❞ (@randecent) on Aug 11, 2017 at 6:56pm PDT

Understanding the auto-lol epidemic

Nearly everyone I spoke to believed the auto-lol epidemic is real. But how exactly we as a society arrived at this place of subconscious laughter remains a mystery.

Though "lol" reportedly predates the internet, a man named Wayne Pearson claims to have invented the shorthand in the '80s as a way to express laughter online. As instant messaging and texting became more popular, so did "lol," and at some point, its purpose pivoted from solely signifying laughter to acting as a universal text response.

Caroline Tagg, a lecturer in Applied Linguistic and English Language at Open University in the UK, favors emoji over "lol," but as the author of several books about digital communication — including Discourse of Text Messaging: Analysis of SMS Communication — she's very familiar with the inclusion of laughter in text.

"Over time, its use has shifted, and it has come to take on other meanings — whether that's to indicate a general mood of lightheartedness or signal irony," Tagg confirms. "These different meanings emerge over time and through repeated exposure to the acronym."

In some cases, the decision to include "lol" in a message might be stylistic — "an attempt to come across in a particular way, to perform a particular persona, or to adopt a particular style."

Ultimately, Tagg believes everyone perceives "lol" in text differently, and makes the conscious decision to use the initialism for various reasons, which are usually influenced by "conversational demands."

As for the increase in frequency over time, she noted that if you engage in conversation with someone who's a fan of saying "lol," you could wind up using the term more often. "Generally speaking ... people who are in regular contact with each other do usually develop shared norms of communication and converge around shared uses," she said.

Think of it like a vicious cycle of contagious text laughter.

Embarking on an lol detox

Now that I'm aware of my deep-seated lol dependency, I'm trying my best to change it. I encourage anyone who thinks they might be stuck in an lol rut to do the same.

The way I see it we have two options: Type lol less, or laugh out loud more. The latter sounds pretty good, but if you're committed to keeping your Resting Text Face, here are some tips.

Try to gradually wean yourself off your reliance on lol by ending messages with punctuation marks instead, using a more specific emoji in place of your laughter, or making an effort to better articulate yourself. Instead "lol," maybe, "omg that's hilarious," for example.

At the very least, try changing up your default laugh setting once in a while. Different digital laughs carry different connotations. If you're ever in doubt about which to use, you can reference this helpful guide:

LOL/HAHA — I really think this thing is hilarious as shown by my caps!

Lol — Bitch, please OR I have nothing to say.

lollllllllll — Yo, that's pretty funny.

el oh el — So unfunny I feel the need to type like this.

haha — Funny but not worth much of my time.

hahahaha — Funny and worth my time!

hah/ha — This is not amusing at all and I want to make that known.

HA — Yes! Finally!

Lmao/Lmfao — When something evokes more comedic joy than "lol" does.

LMAO/LMFAO — Genuine, impassioned laughter, so strong you feel as though your rear end could detach from your body.

Hehehe — You are softly giggling, were just caught doing something semi-suspicious or sexting, or are a small child or a serial killer. This one really varies.

heh — Sure! Bare minimum funny, I guess! Whatever!

In very special cases, consider clarifying that you are literally laughing out loud. As someone who's received a few "Actually just laughed out loud" messages in my lifetime, I can confirm that they make me feel much better than regular lol messages.

One of the major reasons we rely so heavily on representations like "lol" in digital interactions is because we're desperately searching for ways to convey emotions and expressions that can easily be picked up on in face-to-face conversations. It works well when done properly, but we've abused lol's polysemy over the years. After all the term has done for us, it deserves a break.

If we make the conscious effort to scale back, we might be able to prevent "lol" from losing its intended meaning entirely.

WATCH: How scientists are working to prevent your body from being 'hacked'

#_category:yct:001000002#_author:Nicole Gallucci#_lmsid:a0Vd000000DTrEpEAL#_uuid:be58bf7d-b237-3847-bb74-89d253cc0906#_revsp:news.mashable

0 notes

Text

Is Sustainable Off Grid Living Really Possible?

Living independently from big corporations and the 9-5 sounds like a dream, but it can quickly become a nightmare.

Most of us — at some point or other — have entertained thoughts of disengaging from everyday life. Our world can be chaotic and restless. So that the contrast of an imagined peaceful, and much slower independent way of living, calls out to us.

Most people think of going “off the grid” when they express a desire to move away from the structures of everyday life. But the phrase has different meanings for different people, and some definitions are more realistic than others.

Helpful resources: https://survivalistgear.co/emergency-survival-kit/

How independent?

Off-grid living is generally understood to be a way of life that is not dependent on public utilities such as the electrical “grid” (where the term comes from) and water networks.

But some go further than that, interpreting it as a form of life that avoids pretty much everything — including even the roads. This most extreme form — complete independence — likely only exists in parts of the world where that sort of living is a necessity and is an increasingly scarce way of life.

A more common group of people have confiscated the term to identify with a reduced-standard of living that is cleaner and semi-independent. A way of life that might enable a type of full-time touring if they live in a motorhome, or one that enables periodic independence depending on the seasons and other factors.

The Law

Living off the grid is so uncommon that the general presumption is that it must be illegal, at least in parts. It is not illegal, but it is strongly discouraged. For example, in the UK one can only live on a plot of land for 28-days without needing permission to do so by the local authorities. In the United States the situation is similar, and you will need to provide a permit after a while.

So living off-grid would not be as easy as taking a one-way trip up to a place with good soil and building a cabin. Not unless one has permission to do so.

You can however, attempt to live off-grid on your own property, or someone else’s if you have permission. Oftentimes this isn’t as romantic as it seems. Caravans parked on driveways are allowed. Gardens too if they are big enough. This is called ancillary accommodation.

A final option is to live nomadically in a camper van or motorhome with no real fixed address. But this will hardly be an “off grid” lifestyle by most measures, and it will be a struggle to convince an insurance company to cover your motorhome if you don’t technically live anywhere.

Healthcare

In the United States, if you continue working, you might still be able to pay for health insurance through your job. But if you are self-employed or living off of the land, you can open up a health savings account. Accounts like these are often tax-deductible and can really come in handy if you find yourself staring down the barrel at thousands of dollars’ worth in medical bills. If you do not have a fixed-address, or a semi-permanent address, then do your research clearly and make sure this is known to the medical authorities.

Residents in the UK are entitled to free at-the-point-of-use healthcare, the NHS. Living nomadically, or a way of life that does not pay into the system does not disqualify a natural-born citizen from accessing the healthcare system. The point is if using the NHS disqualifies any claim to be truly living off the grid. The healthcare “grid” is probably one exception that even the most extremely independent people would have no qualms about using, even in non-emergencies.

Fixed-abode or not, one still needs to be registered to use the NHS, on their data systems. That means that some type of fixed-address is needed. A fixed-address could be a relative or friend’s house, and will determine your local health clinic; GP doctor and hospital.

If you are unwell anywhere in the country, any and every hospital will open up its doors to help. But they will only do the bare minimum that is necessary. Everything else: follow-ups, check-ups, serious dental work and future operations, has to be sorted by the practitioners local to your fixed address.

For the more casual off-grid observers, a fixed-address makes it possible to vote in elections, and generally “keep in touch” with the outside world, even for insurance or other reasons. Note that this is not a legal requirement, just a convenient one.

Water

Unfortunately, many streams and lakes on both sides of the Atlantic are either polluted or home to organisms that can make a person very sick (or both). It is better to treat water first. Water can be treated by leaving it in direct, harsh sunlight for about eight hours. The ultraviolet radiation should then kill all of the harmful germs. This is very impractical though; time-consuming, and depends on weather conditions.

If the area has a naturally high water table, drilling a well is possible. But permission will be needed and the entire operation can cost thousands of pounds, with no success guaranteed. A deep well also requires a good pump to extract the water. Rain barrels can collect water, but have to be partly-buried so that the wind doesn’t blow them over. Then there is the issue of carrying the water, and protecting it from freezing in the winter.

Of all the aspects of off-grid living, water extraction is probably the most difficult to accomplish naturally and independently. Many extreme off-grid enthusiasts still rely on water from public taps for drinking, showering, and washing.

Helpful reading

https://survivalistgear.co/how-to-desalinate-water/

https://survivalistgear.co/water-storage-emergency-how-to/

Food

Food is another very difficult one. There are two options: foraging and growing. Like off-grid living generally, foraging is not illegal in the UK but is strongly discouraged. In the United States, however, many federal and local foraging laws have been described as “wrongheaded and draconian”. So while one law generally applies for much of the UK (foraging laws are much the same but generally more relaxed in Scotland), the complexities of the many local and federal laws in the United States require some serious research beforehand.

In the United States both foraging and trespassing can be criminal offences, but not in the UK. There it is technically not illegal to forage — even on private land. If you are caught by the landowner and asked to leave, you should do so. But trespassing is not a criminal offence. Foraging is described in the Theft Act of 1968 as the art of a person: “…who picks mushrooms growing wild on any land, or who picks flowers, fruit or foliage from a plant”. The landowner may be able to ask you to leave, but they cannot ask for foraged goods back — as that would be stealing.

Foraging is a careful and slow skill, and it is unlikely a person can do it for sustainable living. Rather, foraging is more like a seasonal hobby. Actually, the same can be thought of for growing food.

Raised beds, containers, and small gardens can all produce seasonal foods to eat and enjoy. But also leave one vulnerable to pests, the weather, and disease. Cafes and supermarkets dispose of food waste and cardboard — a source of potential compost — but some would argue this is still living “on” the grid.

Growing food is technically do-able, but terribly inconvenient. People often report digestive problems, bad breath, and sickness from eating the same foods. And almost everyone will need to fall back on the supermarket “grid” from time to time.

Helpful resources: https://survivalistgear.co/emergency-survival-food/

Energy

Being off the electrical grid — surprisingly — is perhaps one of most practical things one can do, thanks to advances in technology. But being energy efficient may require sacrifices, such as the microwave oven; toasters, coffee-makers, TVs and so on. But you can watch TV on a laptop instead, and get a cafetière for the latter two. LED bulbs are a powerful way to reduce wastage through lighting.

A good 100-watt solar panel should serve the energy needs of about two people, and you can buy mounted-roof ones to put away (if you are worried about theft). If they are looked after properly, a solar panel can produce power successfully for over a decade.

Gas is important for keeping things cool in the fridge, and for keeping warm in the winter. Buying gas canisters from the grid is unavoidable, and largely essential. But like the solar panel — and any generators that might be needed for back-up — some dependency on the grid will remain, but it will be sharply reduced.

Conclusions

It may be possible to live truly, independently, off-grid as a short-term experiment. But in the long-run, and depending on your interpretation of what “off-grid” entails, there will always come a time when it is necessary to re-engage with the structures of society. Whether that time comes in the darkest coldest nights of winter, stocking up on food, or in a medical emergency, and so on.

Off-grid living may even be more expensive, rather than cheaper, than “normal” living, too. After all, there will still be propane bills and other expenses. And in the end, your home, if it is a cabin or motorhome, will be a depreciating — and not appreciating — asset.

It is an idyllic thought, but one that most often fails to match up with reality.

— This Author

Neil Wright is researcher and copywriter. He is passionate about the great outdoors and the natural world, and has written extensively about the off-grid lifestyle and living off the land in the UK on his website.

Image Source: Shutterstock, royalty-free stock photo ID: 532886983

The post Is Sustainable Off Grid Living Really Possible? appeared first on .

source https://survivalistgear.co/living-off-the-grid/ source https://survivalistgear1.tumblr.com/post/626818795593498624

0 notes

Text

Is Sustainable Off Grid Living Really Possible?

Living independently from big corporations and the 9-5 sounds like a dream, but it can quickly become a nightmare.

Most of us — at some point or other — have entertained thoughts of disengaging from everyday life. Our world can be chaotic and restless. So that the contrast of an imagined peaceful, and much slower independent way of living, calls out to us.

Most people think of going “off the grid” when they express a desire to move away from the structures of everyday life. But the phrase has different meanings for different people, and some definitions are more realistic than others.

Helpful resources: https://survivalistgear.co/emergency-survival-kit/

How independent?

Off-grid living is generally understood to be a way of life that is not dependent on public utilities such as the electrical “grid” (where the term comes from) and water networks.

But some go further than that, interpreting it as a form of life that avoids pretty much everything — including even the roads. This most extreme form — complete independence — likely only exists in parts of the world where that sort of living is a necessity and is an increasingly scarce way of life.

A more common group of people have confiscated the term to identify with a reduced-standard of living that is cleaner and semi-independent. A way of life that might enable a type of full-time touring if they live in a motorhome, or one that enables periodic independence depending on the seasons and other factors.

The Law

Living off the grid is so uncommon that the general presumption is that it must be illegal, at least in parts. It is not illegal, but it is strongly discouraged. For example, in the UK one can only live on a plot of land for 28-days without needing permission to do so by the local authorities. In the United States the situation is similar, and you will need to provide a permit after a while.

So living off-grid would not be as easy as taking a one-way trip up to a place with good soil and building a cabin. Not unless one has permission to do so.

You can however, attempt to live off-grid on your own property, or someone else’s if you have permission. Oftentimes this isn’t as romantic as it seems. Caravans parked on driveways are allowed. Gardens too if they are big enough. This is called ancillary accommodation.

A final option is to live nomadically in a camper van or motorhome with no real fixed address. But this will hardly be an “off grid” lifestyle by most measures, and it will be a struggle to convince an insurance company to cover your motorhome if you don’t technically live anywhere.

Healthcare

In the United States, if you continue working, you might still be able to pay for health insurance through your job. But if you are self-employed or living off of the land, you can open up a health savings account. Accounts like these are often tax-deductible and can really come in handy if you find yourself staring down the barrel at thousands of dollars’ worth in medical bills. If you do not have a fixed-address, or a semi-permanent address, then do your research clearly and make sure this is known to the medical authorities.

Residents in the UK are entitled to free at-the-point-of-use healthcare, the NHS. Living nomadically, or a way of life that does not pay into the system does not disqualify a natural-born citizen from accessing the healthcare system. The point is if using the NHS disqualifies any claim to be truly living off the grid. The healthcare “grid” is probably one exception that even the most extremely independent people would have no qualms about using, even in non-emergencies.

Fixed-abode or not, one still needs to be registered to use the NHS, on their data systems. That means that some type of fixed-address is needed. A fixed-address could be a relative or friend’s house, and will determine your local health clinic; GP doctor and hospital.

If you are unwell anywhere in the country, any and every hospital will open up its doors to help. But they will only do the bare minimum that is necessary. Everything else: follow-ups, check-ups, serious dental work and future operations, has to be sorted by the practitioners local to your fixed address.

For the more casual off-grid observers, a fixed-address makes it possible to vote in elections, and generally “keep in touch” with the outside world, even for insurance or other reasons. Note that this is not a legal requirement, just a convenient one.

Water

Unfortunately, many streams and lakes on both sides of the Atlantic are either polluted or home to organisms that can make a person very sick (or both). It is better to treat water first. Water can be treated by leaving it in direct, harsh sunlight for about eight hours. The ultraviolet radiation should then kill all of the harmful germs. This is very impractical though; time-consuming, and depends on weather conditions.

If the area has a naturally high water table, drilling a well is possible. But permission will be needed and the entire operation can cost thousands of pounds, with no success guaranteed. A deep well also requires a good pump to extract the water. Rain barrels can collect water, but have to be partly-buried so that the wind doesn’t blow them over. Then there is the issue of carrying the water, and protecting it from freezing in the winter.

Of all the aspects of off-grid living, water extraction is probably the most difficult to accomplish naturally and independently. Many extreme off-grid enthusiasts still rely on water from public taps for drinking, showering, and washing.

Helpful reading

https://survivalistgear.co/how-to-desalinate-water/

https://survivalistgear.co/water-storage-emergency-how-to/

Food

Food is another very difficult one. There are two options: foraging and growing. Like off-grid living generally, foraging is not illegal in the UK but is strongly discouraged. In the United States, however, many federal and local foraging laws have been described as “wrongheaded and draconian”. So while one law generally applies for much of the UK (foraging laws are much the same but generally more relaxed in Scotland), the complexities of the many local and federal laws in the United States require some serious research beforehand.

In the United States both foraging and trespassing can be criminal offences, but not in the UK. There it is technically not illegal to forage — even on private land. If you are caught by the landowner and asked to leave, you should do so. But trespassing is not a criminal offence. Foraging is described in the Theft Act of 1968 as the art of a person: “…who picks mushrooms growing wild on any land, or who picks flowers, fruit or foliage from a plant”. The landowner may be able to ask you to leave, but they cannot ask for foraged goods back — as that would be stealing.

Foraging is a careful and slow skill, and it is unlikely a person can do it for sustainable living. Rather, foraging is more like a seasonal hobby. Actually, the same can be thought of for growing food.

Raised beds, containers, and small gardens can all produce seasonal foods to eat and enjoy. But also leave one vulnerable to pests, the weather, and disease. Cafes and supermarkets dispose of food waste and cardboard — a source of potential compost — but some would argue this is still living “on” the grid.

Growing food is technically do-able, but terribly inconvenient. People often report digestive problems, bad breath, and sickness from eating the same foods. And almost everyone will need to fall back on the supermarket “grid” from time to time.

Helpful resources: https://survivalistgear.co/emergency-survival-food/

Energy

Being off the electrical grid — surprisingly — is perhaps one of most practical things one can do, thanks to advances in technology. But being energy efficient may require sacrifices, such as the microwave oven; toasters, coffee-makers, TVs and so on. But you can watch TV on a laptop instead, and get a cafetière for the latter two. LED bulbs are a powerful way to reduce wastage through lighting.

A good 100-watt solar panel should serve the energy needs of about two people, and you can buy mounted-roof ones to put away (if you are worried about theft). If they are looked after properly, a solar panel can produce power successfully for over a decade.

Gas is important for keeping things cool in the fridge, and for keeping warm in the winter. Buying gas canisters from the grid is unavoidable, and largely essential. But like the solar panel — and any generators that might be needed for back-up — some dependency on the grid will remain, but it will be sharply reduced.

Conclusions

It may be possible to live truly, independently, off-grid as a short-term experiment. But in the long-run, and depending on your interpretation of what “off-grid” entails, there will always come a time when it is necessary to re-engage with the structures of society. Whether that time comes in the darkest coldest nights of winter, stocking up on food, or in a medical emergency, and so on.

Off-grid living may even be more expensive, rather than cheaper, than “normal” living, too. After all, there will still be propane bills and other expenses. And in the end, your home, if it is a cabin or motorhome, will be a depreciating — and not appreciating — asset.

It is an idyllic thought, but one that most often fails to match up with reality.

— This Author

Neil Wright is researcher and copywriter. He is passionate about the great outdoors and the natural world, and has written extensively about the off-grid lifestyle and living off the land in the UK on his website.

Image Source: Shutterstock, royalty-free stock photo ID: 532886983

The post Is Sustainable Off Grid Living Really Possible? appeared first on .

source https://survivalistgear.co/living-off-the-grid/

0 notes

Text

Quadrotor Safety System Stops Propellers Before You Lose a Finger

With spinning hoops to detect obstacles combined with electromagnetic braking, this quadrotor safety system is both effective and cheap

Photo: Evan Ackerman/IEEE Spectrum

Quadrotors have a reputation for being both fun and expensive, but it’s not usually obvious how dangerous they can be. While it’s pretty clear from the get-go that it’s in everyone’s best interest to avoid the spinny bits whenever possible, quadrotor safety primarily involves doing little more than trying your level best not to run into people. Not running into people with your drone is generally good advice, but the problems tend to happen when for whatever reason the drone escapes from your control. Maybe it’s your fault, maybe it’s the drone’s fault, but either way, those spinny bits can cause serious damage.

Safety-conscious quadrotor pilots have few options for making their drones safer, and none of them are all that great, due either to mediocre effectiveness or significant cost and performance tradeoffs. Now researchers at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, have come up with a clever idea for a quadrotor-safety system that manages to be highly effective, reliable, lightweight, and cheap all at the same time. If that sounds too good to be true, we have video of some hot dogs not getting chopped into bits that might convince you otherwise.

The safest quadrotor that we can think of is probably Flyability’s Gimball, or one of the other drones that uses a wraparound cage. It’s very effective, but comes with a significant size and weight penalty, and it’s particularly annoying for drones with cameras. It’s possible to scale the cages down to completely enclose just the rotors, but that’s potentially just as expensive and also much less aerodynamic. All of these safety systems are passive; active safety is also an option, but then you have to worry about things like sensors and computers always working reliably, along with costs that can escalate quickly.

The ideal drone safety system would provide reliable protection from any obstacle approaching from any direction, and it would do so with a bare minimum of cost and weight. Reliable means that the system really needs to be passive, but it also needs to offer the same protective coverage as a rotor cage without all of that added mass. The University of Queensland researchers have developed a system which meets these criteria, in the form of a swept mechanical interference sensor called the Safety Rotor. It’s a simple idea: A plastic hoop is added to the rotor system that spins around the rotor plane, such that anything that would make contact with the rotor must make contact with the hoop first. And if the hoop senses a contact, it puts the brakes on the rotor, slowing it enough that it’ll turn needing a finger into needing a band-aid.

While the concept here seems simple, the details are what makes it practical. The hoop spins passively, driven by a small amount of friction against the rotor hub that causes it to rotate at a few tens of hertz. This is fast enough for quick obstacle detection, but slow enough that the hoop itself isn’t a danger. The base of the hoop is studded with IR reflectors, which pass in front of an IR detector mounted near the rotor hub. All the system has to do is make sure it keeps getting consistent pings from the detector, and if too much time passes between pings, it means that the hoop has run into something, and the system engages the rotor brake.

The brake itself is electrodynamic, and functions by essentially shorting the motor inputs to turn it into a generator instead. The current generated by the spinning motor opposes the direction of rotation, and the faster the motor is spinning, the stronger this negative torque is. It would be marginally faster to apply voltage to actively decelerate the motor, but that would make the system more complicated and introduce more things that could go wrong. Another advantage of keeping things passive is that total loss of power will cause the braking circuit to activate, as will a safety system that isn’t set up properly.

Image: University of Queensland

To get a sense of how well the Safety Rotor works, let’s first look at the cost— what you have to pay to get it working in the first place. This can be measured in a bunch of ways, but the first is with money, and the good news is that the researchers estimate that integrating four Safety Rotors on an average drone would cost just over $14. It’ll also cost efficiency, but not all that much: Total weight added is under 22 grams, and aerodynamic effects don’t seem to be significant. The end-user also has to pay with their time and effort to set the system up and keep it running, but it’s quite simple, and doesn’t require skill to operate once it’s installed.

For that cost, what do you get? The researchers did some experiments, and this is what they found:

The measured latency [of the Safety Rotor’s braking response] was 0.0118 seconds from the triggering event to start of rotor deceleration. The rotor required a further 0.0474 s to come to a complete stop. Ninety percent of the rotational kinetic energy of the rotor (as computed from angular velocity) was dissipated within 0.0216 s of triggering, and 99 percent of the rotational kinetic energy of the rotor was dissipated within 0.032 s.

The safety functionality of the safety system was tested on the bench using a processed meat “finger” proxy to trigger the hoop, and also applied to an open rotor (without hoop) for comparison. The rotor was spun at hover speed (1100 rads−1) and the finger proxy was introduced into the hoop at 0.36 ms−1 … The rotor and finger motion were captured using a shutter speed of 480 Hz. The rotor came to a stop within 0.077 s, with only light marks on the finger proxy from the impact of the hoop. The rotor was completely stopped by the time the finger reached the rotor plane. In contrast, the tip of the finger proxy introduced to an open rotor was completely destroyed.

Ouch.

The faster the quadrotor is moving, of course, the less effective the safety system will be, since the time between hoop contact and rotor contact decreases and there won’t be as much of a chance for the rotor braking to take effect. Performance will be highest during low-speed maneuvering, take-offs, and landings, but these are situations in which quadrotors seem to present the most consistent danger to both operators and bystanders. And again, it’s really a question of how much benefit you get in exchange for the cost.

Fifteen to $20 for a safety system with this level of performance is super cheap relative to the price of most consumer quadrotors, especially when you consider that add-ons like simple propeller bumpers cost $10 to $20 all by themselves, and more comprehensive safety systems like propeller cages can run well over $100. Even if manufacturers were to make this kind of safety system an option that consumers could electively bear the entire cost of, it seems like it would be an easy choice for anyone just starting out, considering how significant the upsides are and how insignificant the downsides seem to be. Personally, I’d happily pay it—if it never comes in handy, I’d be out $20, but if it saves even one finger, that’s priceless. Or it’s however much a new finger costs nowadays, I guess.

For more details, we spoke with Paul Pounds via email.

IEEE Spectrum: Why do you think someone hasn’t come up with a safety system like this before?

Paul Pounds: It has been difficult enough making quadrotors fly for useful lengths of time, that heavy and expensive systems haven’t been at the top of the priority list for manufacturers. Now that quadrotors are increasingly common and in use by non-professionals, the industry needs to take notice of the danger their products pose.

You mention that subjectively, the quadrotor was somewhat more difficult to pilot during testing. Can you elaborate on the potential downsides of the system?

We modified an off-the-shelf commercial system to show that retrofitting into existing products was straight-forward. In this case, we had to use slightly smaller rotors to get more hoop clearance, and since we could not return the flight controller to compensate for the change in size, it becomes more twitchy. This was a matter of a tuning problem due to a closed-source platform. The actual system itself has very few drawbacks—only a slight increase in weight and cost over an unsafe aircraft and the need to reset the safety system after a crash.

How much of a risk is there of one of the hoops being slowed enough to trigger the system in-flight by a non-impact? Is in-flight recovery possible?

After our initial tuning, a non-commanded triggering has not happened during our test flights. We can adjust how sensitive the trigger action is. We foresee that an aircraft with six or more rotors can employ a smart safety scheme where one rotor will stop in flight, while redundant rotors can keep providing thrust. Once the hoop detects that it is clear again, it can restart the stopped rotor to continue flying.

What do you think will be the biggest obstacle to adoption of this system in commercial products?

I see the biggest obstacle to commercializing this technology is that big manufacturers will not be prepared to accept the extra cost of making their aircraft safe. Even though the system is very cheap, it requires them to do more than the most basic implementation of their product, and that could have cut into their profit margins. I think savvy companies will realise that mitigating their liability for producing a dangerous product used by the general public is well worth a small hit to the bottom line, and potentially something that many people would pay an extra $20 for.

Have you (personally) tested the system?

I have tested it using a weighted mechanical substitute, in place of a rotor, and it worked great. My fiancée would be very mad at me if I tried it with a rotor for real, no matter how much I tell them that it’s very safe!

What are you working on next?

I’m always working on something different! We are just finishing a project to build a quadrotor that has three times the endurance of a conventional design— a two kilo drone able to fly up to 90 minutes carrying a GoPro camera payload. We have new airspeed velocity sensors that allow drones to instantly reject gust disturbances, making them safer and more reliable to fly around buildings. And, of course, a few more secret projects that I can’t talk about yet!

We’ve posted about some of Paul’s work before, including this hybrid quadrotor helicopter from IROS 2013. His electromechanical never fails to impress, and we’re very much looking forward to hearing more about those secret projects.

“The Safety Rotor—An Electromechanical Rotor Safety System for Drones,” by Paul E. I. Pounds and Will Deer from the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, was presented at ICRA 2018.

Quadrotor Safety System Stops Propellers Before You Lose a Finger syndicated from https://jiohowweb.blogspot.com

0 notes

Text

Quadrotor Safety System Stops Propellers Before You Lose a Finger

With spinning hoops to detect obstacles combined with electromagnetic braking, this quadrotor safety system is both effective and cheap

Photo: Evan Ackerman/IEEE Spectrum

Quadrotors have a reputation for being both fun and expensive, but it’s not usually obvious how dangerous they can be. While it’s pretty clear from the get-go that it’s in everyone’s best interest to avoid the spinny bits whenever possible, quadrotor safety primarily involves doing little more than trying your level best not to run into people. Not running into people with your drone is generally good advice, but the problems tend to happen when for whatever reason the drone escapes from your control. Maybe it’s your fault, maybe it’s the drone’s fault, but either way, those spinny bits can cause serious damage.

Safety-conscious quadrotor pilots have few options for making their drones safer, and none of them are all that great, due either to mediocre effectiveness or significant cost and performance tradeoffs. Now researchers at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, have come up with a clever idea for a quadrotor-safety system that manages to be highly effective, reliable, lightweight, and cheap all at the same time. If that sounds too good to be true, we have video of some hot dogs not getting chopped into bits that might convince you otherwise.

The safest quadrotor that we can think of is probably Flyability’s Gimball, or one of the other drones that uses a wraparound cage. It’s very effective, but comes with a significant size and weight penalty, and it’s particularly annoying for drones with cameras. It’s possible to scale the cages down to completely enclose just the rotors, but that’s potentially just as expensive and also much less aerodynamic. All of these safety systems are passive; active safety is also an option, but then you have to worry about things like sensors and computers always working reliably, along with costs that can escalate quickly.

The ideal drone safety system would provide reliable protection from any obstacle approaching from any direction, and it would do so with a bare minimum of cost and weight. Reliable means that the system really needs to be passive, but it also needs to offer the same protective coverage as a rotor cage without all of that added mass. The University of Queensland researchers have developed a system which meets these criteria, in the form of a swept mechanical interference sensor called the Safety Rotor. It’s a simple idea: A plastic hoop is added to the rotor system that spins around the rotor plane, such that anything that would make contact with the rotor must make contact with the hoop first. And if the hoop senses a contact, it puts the brakes on the rotor, slowing it enough that it’ll turn needing a finger into needing a band-aid.

While the concept here seems simple, the details are what makes it practical. The hoop spins passively, driven by a small amount of friction against the rotor hub that causes it to rotate at a few tens of hertz. This is fast enough for quick obstacle detection, but slow enough that the hoop itself isn’t a danger. The base of the hoop is studded with IR reflectors, which pass in front of an IR detector mounted near the rotor hub. All the system has to do is make sure it keeps getting consistent pings from the detector, and if too much time passes between pings, it means that the hoop has run into something, and the system engages the rotor brake.

The brake itself is electrodynamic, and functions by essentially shorting the motor inputs to turn it into a generator instead. The current generated by the spinning motor opposes the direction of rotation, and the faster the motor is spinning, the stronger this negative torque is. It would be marginally faster to apply voltage to actively decelerate the motor, but that would make the system more complicated and introduce more things that could go wrong. Another advantage of keeping things passive is that total loss of power will cause the braking circuit to activate, as will a safety system that isn’t set up properly.

Image: University of Queensland

To get a sense of how well the Safety Rotor works, let’s first look at the cost— what you have to pay to get it working in the first place. This can be measured in a bunch of ways, but the first is with money, and the good news is that the researchers estimate that integrating four Safety Rotors on an average drone would cost just over $14. It’ll also cost efficiency, but not all that much: Total weight added is under 22 grams, and aerodynamic effects don’t seem to be significant. The end-user also has to pay with their time and effort to set the system up and keep it running, but it’s quite simple, and doesn’t require skill to operate once it’s installed.

For that cost, what do you get? The researchers did some experiments, and this is what they found:

The measured latency [of the Safety Rotor’s braking response] was 0.0118 seconds from the triggering event to start of rotor deceleration. The rotor required a further 0.0474 s to come to a complete stop. Ninety percent of the rotational kinetic energy of the rotor (as computed from angular velocity) was dissipated within 0.0216 s of triggering, and 99 percent of the rotational kinetic energy of the rotor was dissipated within 0.032 s.

The safety functionality of the safety system was tested on the bench using a processed meat “finger” proxy to trigger the hoop, and also applied to an open rotor (without hoop) for comparison. The rotor was spun at hover speed (1100 rads−1) and the finger proxy was introduced into the hoop at 0.36 ms−1 … The rotor and finger motion were captured using a shutter speed of 480 Hz. The rotor came to a stop within 0.077 s, with only light marks on the finger proxy from the impact of the hoop. The rotor was completely stopped by the time the finger reached the rotor plane. In contrast, the tip of the finger proxy introduced to an open rotor was completely destroyed.

Ouch.

The faster the quadrotor is moving, of course, the less effective the safety system will be, since the time between hoop contact and rotor contact decreases and there won’t be as much of a chance for the rotor braking to take effect. Performance will be highest during low-speed maneuvering, take-offs, and landings, but these are situations in which quadrotors seem to present the most consistent danger to both operators and bystanders. And again, it’s really a question of how much benefit you get in exchange for the cost.

Fifteen to $20 for a safety system with this level of performance is super cheap relative to the price of most consumer quadrotors, especially when you consider that add-ons like simple propeller bumpers cost $10 to $20 all by themselves, and more comprehensive safety systems like propeller cages can run well over $100. Even if manufacturers were to make this kind of safety system an option that consumers could electively bear the entire cost of, it seems like it would be an easy choice for anyone just starting out, considering how significant the upsides are and how insignificant the downsides seem to be. Personally, I’d happily pay it—if it never comes in handy, I’d be out $20, but if it saves even one finger, that’s priceless. Or it’s however much a new finger costs nowadays, I guess.

For more details, we spoke with Paul Pounds via email.

IEEE Spectrum: Why do you think someone hasn’t come up with a safety system like this before?

Paul Pounds: It has been difficult enough making quadrotors fly for useful lengths of time, that heavy and expensive systems haven’t been at the top of the priority list for manufacturers. Now that quadrotors are increasingly common and in use by non-professionals, the industry needs to take notice of the danger their products pose.

You mention that subjectively, the quadrotor was somewhat more difficult to pilot during testing. Can you elaborate on the potential downsides of the system?

We modified an off-the-shelf commercial system to show that retrofitting into existing products was straight-forward. In this case, we had to use slightly smaller rotors to get more hoop clearance, and since we could not return the flight controller to compensate for the change in size, it becomes more twitchy. This was a matter of a tuning problem due to a closed-source platform. The actual system itself has very few drawbacks—only a slight increase in weight and cost over an unsafe aircraft and the need to reset the safety system after a crash.

How much of a risk is there of one of the hoops being slowed enough to trigger the system in-flight by a non-impact? Is in-flight recovery possible?

After our initial tuning, a non-commanded triggering has not happened during our test flights. We can adjust how sensitive the trigger action is. We foresee that an aircraft with six or more rotors can employ a smart safety scheme where one rotor will stop in flight, while redundant rotors can keep providing thrust. Once the hoop detects that it is clear again, it can restart the stopped rotor to continue flying.

What do you think will be the biggest obstacle to adoption of this system in commercial products?

I see the biggest obstacle to commercializing this technology is that big manufacturers will not be prepared to accept the extra cost of making their aircraft safe. Even though the system is very cheap, it requires them to do more than the most basic implementation of their product, and that could have cut into their profit margins. I think savvy companies will realise that mitigating their liability for producing a dangerous product used by the general public is well worth a small hit to the bottom line, and potentially something that many people would pay an extra $20 for.

Have you (personally) tested the system?

I have tested it using a weighted mechanical substitute, in place of a rotor, and it worked great. My fiancée would be very mad at me if I tried it with a rotor for real, no matter how much I tell them that it’s very safe!

What are you working on next?

I’m always working on something different! We are just finishing a project to build a quadrotor that has three times the endurance of a conventional design— a two kilo drone able to fly up to 90 minutes carrying a GoPro camera payload. We have new airspeed velocity sensors that allow drones to instantly reject gust disturbances, making them safer and more reliable to fly around buildings. And, of course, a few more secret projects that I can’t talk about yet!

We’ve posted about some of Paul’s work before, including this hybrid quadrotor helicopter from IROS 2013. His electromechanical never fails to impress, and we’re very much looking forward to hearing more about those secret projects.

“The Safety Rotor—An Electromechanical Rotor Safety System for Drones,” by Paul E. I. Pounds and Will Deer from the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, was presented at ICRA 2018.

Quadrotor Safety System Stops Propellers Before You Lose a Finger syndicated from https://jiohowweb.blogspot.com

0 notes