#camille mauclair

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Camille Mauclair Interieur Bourgeois 1917 Pastel 30 x 47,5 cm

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

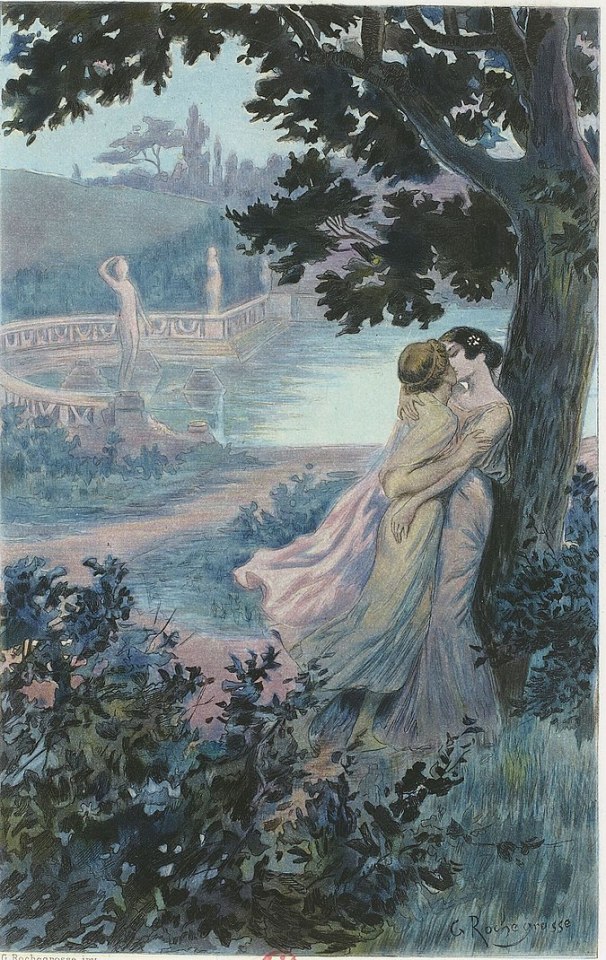

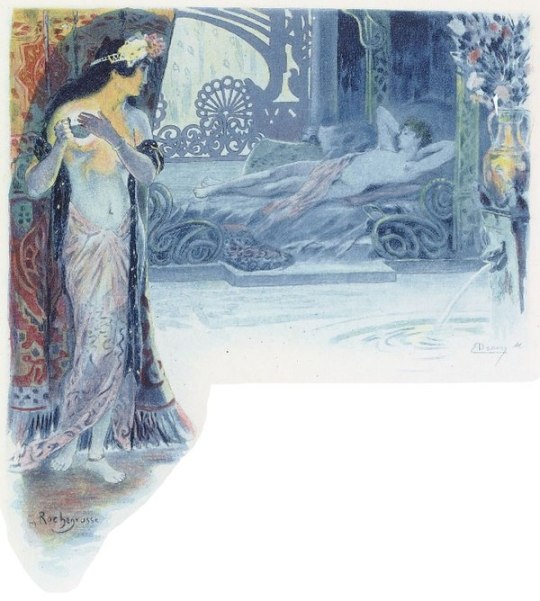

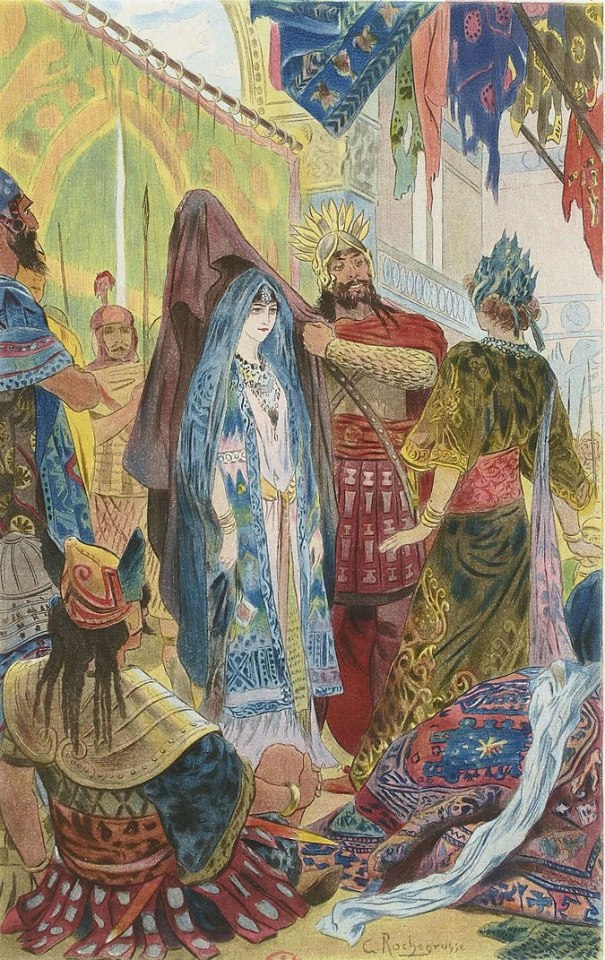

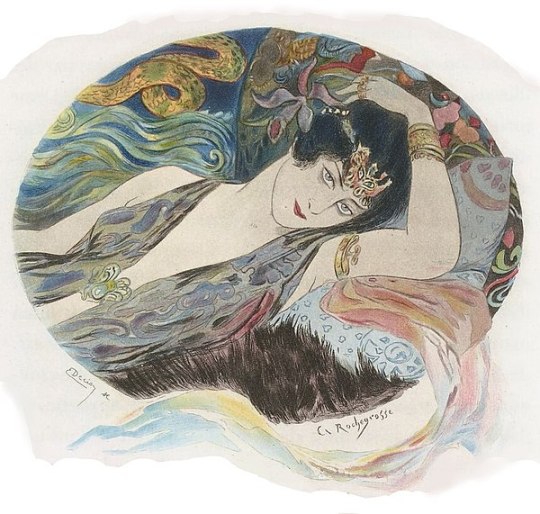

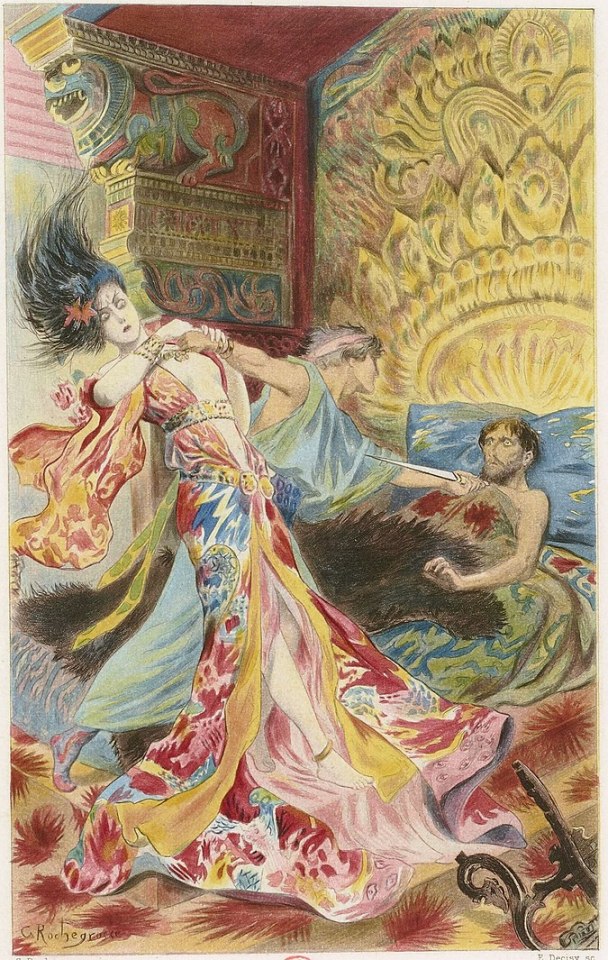

Illustration for Camille Mauclair's ‘Le Poison des Pierreries’ by Georges Rochegrosse, c. 1903.

#georges rochegrosse#vintage art#classic art#art#art history#old art#art details#vintage#moody art#illustration

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Poison des Pierreries

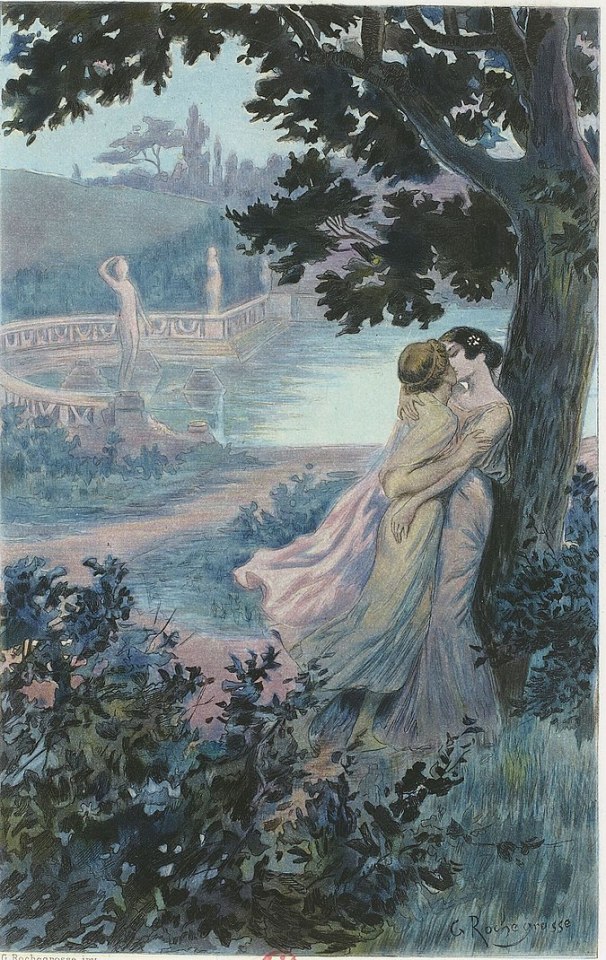

Two women kissing in nature, by Georges Rochegrosse (1859-1938).

This is such a sweet picture. I’ve seen it pop up a few times on Tumblr.

And now I am going to ruin it. But then I’m going to try and unruin it! However, if you just want two girls kissing in nature then scroll on by and vote in some polls. It’s all good.

So this is an illustration from 1903 French novelette Le Poison des Pierreries (The Poisoned Stones) The two characters kissing are the Princess Alilat (the tall brunette) and the Prince Sparyanthis (the blond). Sparyanthis is eighteen years old and we weren’t yet at the point where we required super-buffness to indicate masculinity, so the artist depicts him as a pretty youth. But don’t stop reading! Because 1.) this is a tale of eroticism, revenge, obsession, and treacherous murder by sorcery, and who doesn’t love all that? and 2.) there is nothing straight about this couple or this novel.

Also, 3.) it’s pretty sexy. So, you know. Be aware fellow asexuals.

Le Poison des Pierreries was written by the author and essayist Camille Mauclair for his friend the Orientalist Georges Rochegrosse to illustrate. Orientalism was very pretty but very, very problematic and if you don’t know why you can easily find out by doing a search.

(BTW I am not an expert on textual analysis or art history, or queer and gender theory, and know almost nothing about the French language — when I get stuff wrong feel free to let me know! I’m sure at the very least there are lots of classical allusions I’m missing.)

Also: there’s some implied lack of consent in this story.

The novelette tells of the distant city of Etesia. It is ruled by two brothers, the doughty warrior Cimmérion and the beautiful, decadent Sparyanthis. They are really really fond of each other. But in a way that wasn’t a big deal in 1903.

Cimmérion arrives home from war with the beautiful princess Alilat whom he has forced into marriage. Alilat is now the last of her house, thanks to Cimmérion, because he’s slaughtered everyone she ever knew, and she has opinions about this. Despite Sparyanthis’ best intentions, Alilat beguiles him, and they begin having an affair while Cimmérion is away hunting each day. ‘Two women kissing in nature’ is the moment when Sparyanthis finally gives in to his desire for Alilat.

But Alilat is (understandably) after revenge for herself and her people, and she uses her sorceries to bring a strange malady upon Cimmérion that robs him of his strength. At the same time she relishes the agonies of guilt Sparyanthis feels over his ongoing betrayal of his beloved brother.

Eventually everyone dies!

But until that happens there is a lot of queer sex going on.

The Queerness

So we can try and read this story as someone from 1903, or we can read it as someone from today. In 1903 it’s a story of masculinity as a vital, conquering, barbarous force versus femininity as a languid, yielding, civilising… perhaps too civilising… influence. A healthy nation was thought to be warlike and ever-expanding. Old civilizations — like the ancient nations of the East — were regarded as rich but dwindling due to becoming too decadent; their sexual mores (which the West took a not at all creepy interest in; c.f. Richard Burton) were held to be intriguing but Not The Done Thing. A proper western couple — one (1) man + one (1) woman, married — had quick, penetrative sex and then went to sleep or something idk. This is how Cimmérion takes Alilat, and she loathes him for it (there’s a line about her ‘being thrown down upon the couch of the conqueror’ and having to endure his caresses). Real men are too busy hunting or making war or running kingdoms to bother much about girls.

But Sparyanthis is quite a different sort of person from his dull brother. He wanders around the palace in women’s clothes having sex with whoever he finds; the explicit incidents are with women, but there are plenty of young men in the illustrations. And everyone is down with it because the Etesians are known for two things: war and having A LOT of sex, never mind with who (at one point Spary can seek out Aliat at night because all the servants are busy making out with all the soldiers in alcoves).

Both in words and illustrations Mauclair and Rochegrosse suggest Sparyanthis is a young woman. He is ‘more beautiful that all the maidens of that country’. He is frequently described as wearing women’s robes, or of being naked except for his jewellery. He is languid and wanton (not vigorous and virile like Cimmérion), with golden tresses and soft, white limbs. There are suggestions that he is sometimes rouged or kohl-eyed, but I don’t trust my translation enough to say for sure. He lays around on couches and beds a lot, and delves into non-manly stuff like magic and secret knowledge. There’s much made of how devoted to each other the two brothers are because of their differences. Soft, white Sparyanthis idolises tanned, brawny, bearded Cimmérion, and Cimmérion ‘adores Sparyanthis’ beautiful body’.

Alilat, meanwhile, is not an Etesian and is accustomed to wearing sombre modest clothing (there is a scene where Sparyanthis invites her to one of his afternoon gambols, and when everyone strips off and starts making out Alilat remains in her black robes and pointedly focuses only on her host, Sparyanthis, and he wonders what’s going on). But once she seduces Sparyanthis, she starts playing with gender too: she frequently meets him dressed in masculine clothes, while he is still in his woman’s garments. She is a vital force, determined as she is to achieve her revenge, and this is juxtaposed with Sparyanthis’ languorous attitude. She is compared to a hunter, and him to the quarry.

Alilat explicitly cannot stand the touch of a man, so she's having an affair with the beautiful, voluptuous Sparyanthis... because neither her nor the story considers him a man.

She intends to destroy both Cimmérion and the city of Etesia, and she takes a devilish glee in how tortured with guilt Sparyanthis is, but she does seem to be as sexually obsessed with him as he is with her. And there are moments of maternal kindness too, where she fondly treats Spary like a younger sister.

So while in 1903 it’s a story of what city-destroying calamities happen when men and women don’t follow their natures or whatever, today it reads like messed up queer people having a lot of queer sex. And I think it’s definitely much more fun to read it that way.

The Sex

So I am asexual and modern sex stuff doesn’t really do much for me. But, tell you what, 1903 veiled door sex knows what it’s about.

Everyone is having great sex here, and it’s implied that because of all this sensuality the kingdom is doomed to fall: the ‘warm voluptuousness’ is ‘softening the men’. You just can’t run a country while everyone’s fucking all the time, and Mauclair is here to tell you all about how bad an idea it is.

No sex is ever described (though it’s taking place in the background of at least one illustration), so the excitement is all in the set-up: Alilat abducts and fucks Sparyanthis while dressed as one of his own archers (“and seized him with the audacity of a soldier taking a weak, conquered Syrian”). A bearded magician approaches Sparyanthis while he is studying the stars in his chambers and traces on the ground with a wand the symbol for an astrological union, and then the 'magician' opens her robe enough to reveal her breasts and they have sex with Alilat still wearing her false beard. I mean

They met in secret caves and rut like beasts, howling, then sit in the throne room in their official robes and give each other secret looks (which, to be fair, is kind of like every new love affair).

Sadly there are no illustrations of any of this! I guess Rochegrosse just wanted to draw beautiful youths embracing and had no time for Mauclair's gender-switching antics, and I think that's a shame.

Anyway, because Cimmérion has laid hands upon Alilat without her permission she has come up with a very particular murder scheme. She tells Sparyanthis that Cimmérion prefers to take her ‘naked save all her jewellery’ and so she enchants her jewellery to burn away his vitality while it caresses his bare skin — the Poisoned Stones of the story’s title. The very act of sex brings about the stoic Cimmérion's murder.

Everyone in Etesia is making out with everyone else, and Cimmérion’s and Alilat’s marriage seems to be the only expected exception to all this polyamoury or so you would think. But then comes the kicker at the end: as Cimmérion lies on his death bed he tells Sparyanthis and Alilat that he knew all about their secret love the whole time and he was totally okay with it: they should carry on with his blessing. Sparyanthis is not okay about that. But too late, bud.

Anyway, not two women kissing in nature, but — I think — two genderqueer people kissing in nature. Read it for yourself! It’s really short!

(Okay, so this is too long already, but Alilat is just so cool. She sends dreams to Spary and begins seducing him before they've even met.

There’s this whole bit where she summons up a spirit of fire from the underworld to infuse her jewellery with wicked magics, and Sparyanthis is like “Do we need to use sorcery? Can’t we just stab him?” and Alilat says “Don’t be such a nerd, Sparyanthis, I wanna do it with evil sex.”

And there’s also another part where she’s wondering about how it will all turn out once Cimmérion is dead, and she’s thinking that maybe she’ll usurp the throne, but then again maybe she’ll just destroy the kingdom and then ride out across the desert as it falls, laughing, and then she’ll go to the mountains and establish her own country of sorceresses and she will be their queen.

And hey, maybe the Alilat who ‘died’ was only a simulacrum and the real Alilat did just that. I hope so, people should just leave a girl alone.)

#Le Poison des Pierreries#French Novel (1903)#Two women kissing in nature#by Georges Rochegrosse (1859-1938)#Playing with gender#Genderqueer#orientalism#A lot of sex#Like a LOT#Sorcery

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

honey just put your sweet lips on my lips, we should just kiss like real people do - part 2/2

Jeffrey McDaniel, The Archipelago of Kisses / Sakuntala, Camille Claudel / William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act I Scene v / "The Kiss", a 12,000-year-old rock painting at Pedra Furada in Brazil / Ig caption / Michael Armitage Kampala Suburb, 2014 / Kenneth Rexroth, "When We with Sappho" / Illustration for Camille Mauclair, Le poison des pierreries (1903) by Georges Rochegrosse / I Know Someone, Mary Oliver / Work Song, Hozier

#web weaving#kiss#kissing#lovecore#hozier#shakespeare#queer#mary oliver#work song#prose#the kiss#moodboard#literature

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Camille Mauclair

On Physical Love,

"Under the whip of pleasure, that merciless torturer." Baudelaire.'

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

so this is actually an illustration for the short story The Poison of Precious Stones (1903) by Camille Mauclair. I'm told it's actually an M/F couple, though I haven't read the story

but I'm choosing to ignore that

Two women kissing in nature, by Georges Rochegrosse (1859-1938).

31K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Almery Lobel-Riche (1880-1950), ''Etudes de Filles'' by Camille Mauclair, 1910

883 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two women kissing in nature by Georges Rochegrosse, 1859-1938

Illustration for Camille Mauclair, Le poison des pierreries (1903)

#georges rochegrosse#kissing#nature#beautiful women#lgbt#art#painting#love#sapphic#lesbian#beauty#garden

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Elle se rassit et s’installa pour dormir (...). Une pénombre douloureuse descendait des cils sur le cercle bleuâtre des paupières, et l’impression d’extrême lassitude, de dignité déçue, d’élégance brisée, donnée par cette belle tête inerte, se prolongeait dans tout l’abandon du corps. Bien des larmes avaient dû brûler sur ces joues mates, mais aussi bien des sourires d’amour avaient dû errer sur cette bouche impérieuse, contractée par une moue de dégoût contenu. Ce visage d’amoureuse au déclin était devant ma curiosité comme un poignant paysage d’automne: l’ombre ne le défendait plus, j’y lisais la vie dans le méandre imperceptible des rides naissantes, légères, mais précises comme des traits de pointe-sèche: et ce masque figé dans une immobilité pareille à la mort avait quelque chose de tragique et d’antique par la fermeté de ses méplats et la netteté de ses ombres. »

Camille Mauclair, Les Passionnés

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

« De plus en plus l'américanisme envahit ces journaux, y tue l'élément pittoresque [... ]Ces moeurs, là comme dans l'industrie, répandent peu à peu leur style morne, apprêté, international. On ne sait plus dans quel pays on se trouve. »

Camille Mauclair — Les Camelots de la pensée.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ANTONIO DE LA GÁNDARA

On this day of 16th December, Antonio de La Gándara (16 December 1861 – 30 June 1917) was born in Paris, France.

He was a painter, pastellist, and draughtsman. His father was of Spanish ancestry, born in Mexico, and his mother was from England. La Gándara's talent was strongly influenced by both cultures.

He was admitted as a student of Jean-Léon Gérôme and Cabanel at the École des Beaux-Arts. Soon, he was recognized by the jury of Salon des Champs-Élysées, where his first work was exhibited: a portrait of Saint Sebastian.

La Gándara had become one of the favourite artists of the Paris elite. His models included Countess Greffulhe, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg, the Princess of Chimay, the Prince de Polignac, the Prince de Sagan, Charles Leconte de Lisle, Paul Verlaine, Leonor Uriburu de Anchorena, Sarah Bernhardt, Romaine Brooks, Jean Moreas, Winnaretta Singer, and Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau.

Influenced by Chardin, his skill is demonstrated in his portraits, in a simplicity with the finest detail, or in the serenity of his scenes of the bridges, parks, and streets of Paris.

Gandara illustrated in publications, including Les Danaïdes by Camille Mauclair, Les Chauves-Souris (The Bats) by the French poet Robert de Montesquiou.

The first exhibition of La Gándara's work organised in New York by Durand-Ruel was a major success and confirmed the painter as one of the masters of his time.

Gandara participated in the most important exhibitions in Paris, Brussels, Berlin, Dresden, Barcelona, and Saragossa.

Although his fame faded rapidly after his death, growing interest in the 20th century saw him regain popularity as a key witness to the art of his time, not only through his canvases but also as the model chosen by the novelists Jean Lorrain and Marcel Proust, and through the anecdotes of his own life narrated by Edmond de Goncourt, Georges-Michel, and Montesquiou.

On 3 November 2018, a major retrospective opened for four months at the Musée Lambinet in Versailles, bringing together more than one hundred works by the painter as well as many documents.

He died on 30 June 1917 and was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

went hunting for this because ashleigh noted it’s nowhere to be found online and this is what i do for a living actually, so:

this appears as an illustration in the book Le Poison des Pierreries (The Poison of Gems) by Camille Mauclair (1903) and it is not titled in the book, but wiki calls it "Ce fut dans un chaud crépuscule" (”It was in a warm twilight”), which is the beginning of the preceding sentence. you can see the individual page here, and read the entire book (in french) here.

Two women kissing in nature by Georges Rochegrosse (1859-1938)

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gli amici Fauves di Matisse: Jelka Rosen

Gli amici Fauves di Matisse: Jelka Rosen

di Sergio Bertolami 44 – I protagonisti La mostra al Salon d’Automne del 1905, aperta al Grand Palais di Parigi, destò, dunque, scandalo. Colpì per l’audacia nell’uso dei colori veementi. Lo scrittore Camille Mauclair disse che «un barattolo di vernice era stato buttato in faccia al pubblico» e col termine “vernice” intendeva proprio il materiale adoperato dagli imbianchini per tinteggiare le…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

This may seem like a melancholy choice for my final post here this season, but as I gaze out my window in the early morning at the rain falling on the deep green of spring, it feels like the perfect thing. One of my great joys this year has been rediscovering my own love of French mélodie, and this haunting piece by Ernest Chausson, sung here by the incomparable Philippe Jaroussky, is a wonderful example of how I found myself back there. It’s also a reminder for all of us to revel in the delicate beauty of the moment, even the darkest of them.

“Les heures“, text by Camille Mauclair, music by Ernest Chausson, from Trois lieder de Camille Mauclair, op. 27 #1

Have a wonderful summer, everyone! - Melinda Beasi

#chausson#ernest amedee chausson#melodie#french#art song#romantic period#19th century#classical music#romantic music#musica in extenso

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Odilon Redon

La Cellule d’or Odilon Redon, 1892-1893 Huile sur toile 30,1 × 24,7 cm Londres, The British Museum

Cette figure emblématique de Redon peinte de profil illustre l’une de ses premières immersions majeures dans le monde de la couleur. Si l’une des caractéristiques de la modernité en peinture est l’accent mis sur la forme et la couleur propre au gré du sujet, Redon avait assurément sa place parmi les modernes. Cependant cette œuvre, de par la technique utilisée, suscita l’incompréhension de la critique contemporaine. Camille Mauclair, critique largement reconnu à son époque, se demandait : “Je comprends peu la relation des tons au dessin et au sujet : pourquoi des bleus ici et des ors là ?”. Ce n’est pas un hasard si Mauclair exprimait la même incompréhension envers les couleurs intenses de Gauguin, couleurs qu’il soupçonnait dictées d’un mouvement mystique et religieux envahissant tant la littérature que la peinture. Les soupçons du critique n’étaient pas infondés. Pendant les années 1890, nombreuses sont, dans la production de Redon, les représentions de femmes en profil, évoquant des prêtresses ou des druidesses. Les doctrines occultistes et théosophes charmaient le peintre qui, à son tour, les utilisait de manière créative et comme source d’inspiration pour sa peinture. Le visage androgyne de la composition peint d’un bleu de cobalt offre de par son intensité un résultat surprenant. La symbolique de la couleur était un sujet fort répandu dans la doctrine mystique de la théosophie. Comme chez Kandinsky, qui accordait une notion spirituelle à la signification des couleurs, on retrouve chez Charles Leadbeater, prêtre et fameux auteur théosophe de l’époque, un passage référent : “bleu léger, comme l’outre-mer ou le cobalt, montre le dévouement à un noble idéal spirituel ; il peut s’élever graduellement à un bleu lilas lumineux, qui indique une spiritualité supérieure et s’accompagne généralement alors de gerbes étincelantes d’étoiles d’or, indices de hautes aspirations spirituelles”. Le fond d’or qui entoure le visage rappelle les icônes byzantines. Combiné avec l’auréole qui entoure la moitié du personnage, il se charge d’une dimension spirituelle.

Texte : Katia Papandreopoulou

https://www.cineclubdecaen.com/peinture/index.html

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Portrait of French writer Camille Mauclair, 1898, Felix Vallotton

1 note

·

View note