#by the way the Catholic inquisition began with the Cathar prosecution

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Headcanon: medieval, religious conflict AU

Based on the religious conflict between the people who believed in Catharism (x) in the Languedoc region of Southern France and the Catholic Church in the early-13th century.

Anna was a daughter of Raymond Roger Trencavel, lord of the fortified town Carcassonne, and several other towns in the Languedoc region. The Threncavels were a Catholic family, but were protective of their subjects regardless of their religious beliefs. Therefore, the Catholics and the Cathars lived in harmony in their towns.

Elsa was a Cathar perfect (i.e. priestess), daughter of a well-respected Cathar perfect couple. She grew up with Anna in Carcassonne, and it was well-known in town that they were childhood sweethearts. When they were teens, they had a silversmith forged a pair of matching necklaces for them to represent their true love (TM).

When Elsa and Anna reached adulthood, the Cathars were deemed as heretics by the Catholic Church, which sent crusades to attack the Languedoc region. Hans and Duke of Weselton were among the crusaders. Hans aimed to destroy the Trencavel family in order to take over (part of) their lands and become a lord. Duke of Weselton joined the crusade because he hated everyone who was not a Catholic, and wanted to exploit the riches of the Trencavels.

In 1209, Carcassonne fell, with Anna’s dad died in prison. All the Cathars were expelled from town. Elsa escaped alone without telling Anna where she was heading. She didn’t want to be found by Anna as she was afraid that Anna would get into troubles by being close to her. On the other hand, Anna desperately tried to find and protect Elsa, whom the crusaders were attempting to hunt down. Since Anna was the daughter of Raymond Trencavel, Hans tempted Anna to marry him by claiming that he would protect her and the people she loved. His intention was to increase his bargain to become a lord in the region through the marriage. Weselton was skeptical of Anna’s religious belief due to her close relationship with Elsa, but Hans confirmed that Anna was a Catholic so that she wouldn’t be prosecuted. Anna had to navigate the dangerous waters to achieve her goal: to protect Elsa at all cost!

Modern day Carcassonne (ref: x)

#i know i know this is super nerdy#by the way the Catholic inquisition began with the Cathar prosecution#then was later extended to including Muslims and witches#so being a Cathar seems to be a good metaphor of being a witch or someone magical#the Cathars were martyrs#i have so much sympathy towards them#the Catholic Church especially the Dominican Order were totally stained with blood#headcanon#elsanna#carcassonne#medieval au#cathar au#my ramblings

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part Two: Well, We’re Here Now

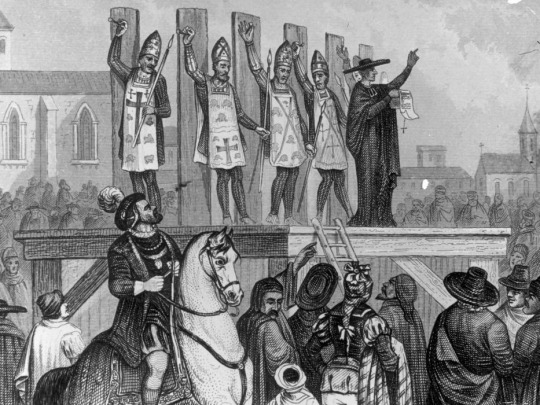

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Here, we have to start with what we can recognize as a proverbial snowball rolling down a hill. Essentially, we have the Catholic church establishing a precedent for getting rid of people who were problematic for them by placing some trumped up charges on them, executing them in a way that makes an example for others whilst simultaneously encapsulating the attention of the commoners, and then carrying on as if they had every justification for making a scene like your mom at a restaurant when they bring out the food and it’s cooler than expected. You can only imagine the out of control spiral into unadulterated chaos that followed, and that, my friends, is known to history as the European Witch Trials (ßthe snowball that is now much larger than when it began rolling at the top of that hill). A few quick notes before we power through this—at this time we can see a multitude of “assassination conspiracies” popping up against one king or another, against the Pope, or against high ranking church officials/the nobility. A bishop is executed for heresy and attempted assassination of Pope John XXII via sorcery, others were arrested with similar charges attached to the very public executions, and ultimately you start to see sorcery, idolatry, and heresy all becoming somewhat synonymous. A few decades later, as we near the central part of the 1300’s, we see the Black Death beginning to rear its ugly head and as fears, tensions, and misinformation mount, people start seeing conspiracies everywhere they look. In 1340 when people start getting grossly sick and some inquisitions start popping up. Spearheaded by the Church, the united heresy combat forces (henceforth known as UHCF—I just came up with that it’s not, like, a term historians use) went out and, as Jesus commanded,

“Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, 20 and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you…” Matthew 28:19-20 (King James Version).

You know what that means (*insert eyebrow waggle here*), of course, they set out to rid the world of anything deemed “heresy” by the Church and that, most certainly, was up for personal interpretation. The reason we hear about these inquisitions getting such a bad rap is because people were genuinely afraid that any action they took might be mistaken for heresy, and without a clear definition of what that entailed they were most certainly right to be afraid. It’s important to highlight a bit of “Inquisition Era” timeline here—in and around 1100 the Catholic Church had, by its own definitions, all but eliminated heresy (whatever that actually means, we may never know), and they did so predominately without harm to those who stood accused. This “era of peace,” we’ll call it, ended around the 12th century when we start to see a spread of some opposing Christian ideas that were not specifically Catholic, and that couldn’t be tolerated. To nip that in the bud, we had some inquisitions come around checking things out. This process usually included, but was not limited to questioning, interrogation, arrest, imprisonment, and torture.

As a general rule, torture was, at least, publicly frowned on in Europe while other countries typically had a death sentence for heretics. As previously mentioned, in the 12th century that all changed when a tiny little papal bull, similar to a public decree, was issued by the not-at-all ironically christened Pope Innocent IV (I, quite frankly, can NOT believe that there were three others prior to this pope who were also called “Innocent” it’s just so god damn pretentious that it physically makes my skin crawl…I digress). The bull allowed torture in 1252, and by 1256 inquisitors who used this form of extracting information were promised absolution by the Church. So, to recap, we have this widespread knowledge of public executions of some of the most prominent figures in the medieval world (like that one guy in charge of the Knights Templar that predicted the deaths of a king and a pope in a non-awkward way that had no bearing on whether or not people believed in the supernatural, I’m sure), the establishment of an anti-heretic police force with little to no oversight and the ability to torture folks at will, and panicked people afraid that if the plague didn’t take them the inquisitors surely would.

To make matters worse, a new papal bull (pesky, those public decrees, I’ll tell ya..) issued around 1450 verified that witchcraft, heresy and a religious group called the Cathars were one in the same which gave them license to prosecute them as heretics or witches without just cause. Without going into too much detail about this, it’s important for you to know that the Cathars called themselves, “the good Christians,” and celebrated a twin deities that represented the God portrayed in the Old Testament, and the other represented the God of Judaism who was a bit synonymous with Satan, or either fathered, seduced, or created Satan (it’s a bit confusing, but that’s what happens when intolerant Christians try and convert believers of other religions to Christianity by way of removing what they originally believed and then replacing it with a more favorable and sort of similar Christian Approved™ bible story—i.e. pagan Ireland, Scotland, or literally any pagan religion in history). You should also know, Cathars essentially saw gender as meaningless and believed in the idea of reincarnation between genders which rendered normal gender roles and other “gender exclusive ideas” as basically useless to them. You can draw your own conclusions about why a male-dominated medieval world run by a religion known for its historical mistreatment of women, wouldn’t have received this idea well.

To reign this all in a bit, we’ve only moved a few centuries away from the establishment of Thomas Aquinas’ rules when we hit a milestone in the 15th century. Occasionally, the Church holds councils to decide on, debate, or discuss church matters, and one such event took place from 1431-1437 called the Council of Basel. Some historians suggest that while a bunch of old men were sitting together talking about stuff for six years that they may have gossiped amongst themselves (as silly men are want to do), and that this may explain the correlating witch trials that coincided with these same dates. It is only about 300 miles from where the council was held and the location of the first trial so you can see how this conclusion is easily drawn. AND NOW WITHOUT FURTHER ADO, it’s time to talk about our first round of witch trials.

The Valais witch trials named so because of its location in Valais in one of the oldest ecclesiastical territories that lies in the southern part of the country separating the Pennine Alps and the Bernese Alps. This region was French and German speaking and that’s important because the German word for witch is hexen, which is where we get the idea of a witch’s hex today, and although we can see an occasional and sporadic burning of witches throughout the 15th century, this marked the first time we see a large-scale systematic persecution for peoples accused of witchcraft/sorcery. It’s also important to point out the lack of accounts that we have during this time period, in part this is due to a general hatred for inquisitors who were in charge of keeping records, and later when the accusations included less heresy and more witchcraft we often see occasions of inquisitors being attacked and records being sabotaged or altogether destroyed. Don’t get me wrong, I can’t blame them, but it makes this part of history a bit more difficult to sus out, and a lot left up to really good detective work or wherever your imagination can take you (this is basically my favorite part). So, that was a long-winded way of saying, a lot of this next part is gonna be me doing my best to make this make sense, and to draw concise and enlightening conclusions that you can read and hopefully learn from (I know I am!).

So, what do we know here? We know that the main record of these trials comes from a guy named Johannes Fründ of Lucerne who was a Swiss clerk of the court, and his account is thought to be the, I won’t say accurate, but more likely only usable document to have an account of these events, though, severely lacking as they were written in the middle of the trials and with only 17 years before they ended. The trials began in the southern French-speaking part of Valais and then spread to the northern German-speaking part where we see a following expansion into the French and Swiss Alps, Savoy, and further into the valleys of Switzerland. It took place a solid fifty years before the witch trials started in Europe, and while the total number of victims is still unknown to us, the estimated death toll is an estimated 400 total men and women. When these accusations began to take place, the duchy of Savoy was recovering from a tumultuous civil war between the noble clans, and in August of 1428, seven delegates representing the districts in Valais insisted that the authorities investigate some supposed instances of witchcraft. If three or more people accused someone of witchcraft or sorcery they were to be arrested, questioned, and made to confess. At a time when torture practices were acceptable forms of interrogation you can see how that might have inspired a few people to confess to being witches without much prompting, but those who refused to do so were tortured until they did. What we know about the victims is that they were more likely women than men, but a significant portion of men were also executed, they were all peasants that were not specifically described as well-educated, but some were. Very few of their names were recorded, and they were not likely elderly as most of them withstood immense torture before they died.

The victims were accused of quite an array of magical experiences including flying, invisibility, removing an illness from one person and issuing it to another, curses, lycanthropy, conspiracy to deprive Christianity of its power, and the most famously known, conspiring with the Devil. These pacts that the witches supposedly entered into with the Devil included trading their souls, paying him taxes, renouncing Christianity, and halting all confession or church-going in exchange for supernatural abilities or an education in the magical arts. Those accused of these crimes were tied to a ladder with a bag of gunpowder hung around their necks, and a wooden crucifix in their arms and then burned alive, others were decapitated first, and even more were tortured to death but were nonetheless burned at the stake for good measure. Now here is where we can see a bit of a conspiracy emerge. Recall from earlier, my mentioning that clergy and nobles alike used witchcraft as an excuse to get rid of people, and just ruminate on that as I tell you that the property of these deceased and accused only passed to their families if they could swear that they were unaware of the sorcery. If they could not prove that, then the land passed to the noble who paid for the execution of these accused. I don’t know about you, but sounds sus to me. This particular genocide is unique to other witch trials in that almost as many men were executed as women, and that leads me to believe a few things: first, that the men were landowners and the nobility wanted the land they were on (would love if a map was available to see this progression, but alas, it has been lost to the sands of time), and two, this wasn’t about gender, but more about the crybaby nobles who were upset that they lost some things during the recent civil war and needed a hobby. It’s not a good look, and it certainly wasn’t without its consequences.

#witches#witch trials#inquisition#medieval europe#itshistoryyall#history#valais#switzerland#valais witch trials#part two#covid-19#coronavirus#what day is it#social distancing

0 notes

Text

Inquisition

Inquisition The Catholic Church’s persecution of heretics, lasting several centuries and spreading throughout Europe and even into the New World. The primary objective of the Inquisition was to eliminate religious threats to the Church, especially powerful sects such as the Waldenses, Bogmils, Cathars and Albigenses, as well as Jews and Muslims. As the Inquisition gathered power, it was turned against Gypsies, social undesirables, people caught in political fights—and witches. Historians estimate that between 200,000 and 1 million people, mostly women, died during the “witch-craze” phase of the Inquisition alone.

The roots of the Inquisition start with the First Crusade launched in 1086 by Pope Urban II, a campaign against Muslims to regain territory in the Holy Land. At the same time, the church found itself beset by religious sects growing in power and influence. The church dealt with these sects unevenly, sometimes with tolerance and sometimes with suppression. In 1184, Pope Lucius III issued a bull to bishops to “make inquisition” for heresy. many bishops were too busy to devote much time to this.

The Inquisition is considered to have begun during the term of Pope Gregory Ix, from 1227 to 1233. In 1229, he invited Franciscan monks to participate in inquisitions, a role that expanded for the order for more than two centuries. In 1233 Gregory issued two bulls giving the Dominican order the authority to prosecute heretics. The Dominicans were empowered to proceed against accused heretics and condemn them without appeal, with the help of the secular arm. The Dominicans became the dominant inquisitors for the church.

In 1307, key members of the knIghts templAr were arrested in France and prosecuted as heretics. The objective of king Philip the Fair was more political than religious; he desired to seize the wealth of the Templars, and he wished to maneuver the church to be subservient to the throne. The Templars were accused of witchcraft and Devil worship as part of their heresy. The first public burning of 54 Templars took place on may 12, 1310, and led to the destruction of the entire order. many Templars were tortured into confessions.

The Inquisition took another deadly turn in the 13th century with the issuance of several bulls that gave inquisitors increasing powers to arrest, torture and execute. After 1250, Pope Innocent IV issued a series of bulls to aid Dominican inquisitors in carrying out their duties. His final bull, Ad Extirpa (“to extirpate”), issued on may 15, 1252, turned Italy into a virtual police state with everyone at the mercy of inquisitors. Anyone who exposed a heretic could have him arrested. The inquisitors had the power to torture people into confessions and sentence them to death by being burned alive at the stake. The bull also put a police force at the disposal of the Inquisition.

Practices of the Inquisition

Manuals.

In the early stages of the Inquisition, there were few official guidelines concerning the arrest, questioning and punishment of heretics. In the 1240s, manuals and handbooks for inquisitors began to circulate, which continued into the 17th century. The most influential early handbook was Practica officii inquisitionis heretice pravitatis, authored in 1323–24 by the famous inquisitor, Bernard Gui. Another famous handbook was the Malleus Maleficarum, written in 1488 by two Dominicans, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger.

Traits of the ideal inquisitor.

Innocent IV issued a bull in 1254 stating that inquisitors should be forceful preachers and “full of zeal for the state.” By the early 14th century, inquisitors were required to be at least 40 years of age; most of them were doctors of law trained at universities.

In his influential manual, Gui sets the requirements for a good inquisitor. Essentially, the man must be inflamed with a passion to eradicate all heresy, but show compassion and mercy too:

The inquisitor . . . should be diligent and fervent in his zeal for the truth of religion, for the salvation of souls, and for the extirpation of heresy. Amid troubles and opposing accidents he should grow earnest, without allowing himself to be inflamed with the fury of wrath and indignation. He must not be sluggish of body, for sloth destroys the vigor of action. He must be intrepid, persisting through danger to death, labouring for religious truth, neither precipitating peril by audacity nor shrinking from it through timidity. He must be unmoved by the prayers and blandishments of those who seek to influence him, yet not be, through hardness of heart, so obstinate that he will yield nothing to entreaty, whether in granting delays or in mitigating punishment, according to place and circumstance, for this implies stubbornness; nor must he be weak and yielding through too great a desire to please, for this will destroy the vigour and value of his work—he who is weak in his work is brother to him who destroys his work. In doubtful matters he must be circumspect and not readily yield credence to what seems probable, for such is not always true; nor should he obstinately reject the opposite, for that which seems improbable often turns out to be fact. He must listen, discuss, and examine with all zeal, that the truth may be reached at the end. Like a judge let him bear himself in passing sentence of corporeal punishment that his face may show compassion, while his inward purpose remains unshaken, and thus will he avoid the appearance of indignation and wrath leading to the charge of cruelty. In imposing pecuniary penalties, let his face preserve the severity of justice as though he were compelled by necessity and not allured by cupidity. Let truth and mercy, which should never leave the heart of a judge, shine forth from his countenance, that his decisions may be free from all suspicion of covetousness or cruelty.

Inquisitors were given full indulgences. They had the power to arrest anyone of any social rank, to seize and sell the property of those they accused and to absolve excommunications. They were both prosecutor and judge. In the early Inquisition, there were many who did their best to pursue truth as they saw it, but many others were corrupted by their power, especially as the Inquisition spread from religious heretics to accused witches.

Arrests and interrogations.

In the early Inquisition, accused heretics were given ample opportunity to turn themselves in and repent. They were notified through priests that they should voluntarily convert. Their names were publicly read at sermons. Failing voluntary action, the accused would be arrested and interrogated. If they capitulated, they might be sentenced to penances, fines, whippings, and imprisonment—sometimes for life. A reformed heretic was useful to the church, both as persuasion to others and also for providing the names of other suspects. Unrepentant and relapsed heretics were tortured and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

If an accused heretic died in jail or prior to arrest, the Inquisition did not hold back, but conducted a posthumous trial. If convicted, the body of the accused was dug up and burned.

Torture.

Initially inquisitors themselves could not perform the torture. In 1256 Pope Alexander IV gave inquisitors the right to absolve each other and give dispensations, so that they could torture the accused themselves.

By the end of the 13th century, inquisitors throughout Europe were operating under Ad Extirpa. Pope John xxII expanded the Inquisition, but did attempt to restrict torture in 1317 by issuing a decree that it should be employed only with “mature and careful deliberation.” Torture could not be repeated without fresh evidence against a person. However, zealous inquisitors found ways around restrictions. For example, torture over a period of time was not repeated torture, but torture that was “continued.” Confessions were always technically “free and spontaneous,” for victims were tortured until they “freely” confessed.

There were six primary methods of torture:

• ordeal by water, in which a person was forced to ingest large quantities of water quickly, which burst blood vessels;

• ordeal by fire, in which the soles of the feet were burned by fire or hot irons;

• the strappado, a pulley, used to hang and drop the accused to dislocate joints;

• the rack, a wooden frame used to stretch a body;

• The wheel, a large cartwheel to which the accused was tied and then beaten with clubs and hammers; and • the stivaletto, wooden planks and metal wedges used to crush feet and legs.

In addition, the accused were imprisoned, sometimes in dungeons, beaten, starved and psychologically abused. Details about how these methods were applied are given in the torture entry.

Execution.

Burning was seen as the only way to exterminate heretics and discourage participation in religious sects. After the corpse was burned, every bone was broken in order to prevent martyrdom and relics for any followers. The organs were burned, and all the ashes were thrown into water.

Accused witches, who were heretics because they were witches, were burned as well. In England, most witches were hung.

Witchcraft and Sorcery

In the extension of its power as a religious, social and political force, the church had long opposed pagan practices and sorcery, especially sacrifices to Demons. From the 8th century to about the 12th century, the church sought to wipe out paganism. By the 13th century, there was more tolerance, and the church itself even acquired an aura of magical power. Practices of alchemy, Magic, sorcery, divination and necromancy were widespread, even in the church. John xxII was well aware of this activity and was a believer himself, using magical talismans for protection. A necromantic plot of sympathetic magic was directed at him and his cardinals. The plot failed, but the pope responded by turning the Inquisition against sorcery.

On July 28, 1319, John XXII ordered the prosecution of two men and a woman who were believed to be consulting with Demons and making magical images. He soon followed with another bull directing the Bishop of Toulouse to proceed against sorcerers as if they were heretics. The bishop accused heretics of sacrificing to and worshipping Demons and making pacts with the Devil.

John XXII was especially interested in wiping out magical practices among the clergy and prominent people, but his campaigns sometimes backfired, making the victims and their works more popular than ever. In 1330 the pope issued a bull ordering that sorcerer and witch trials be concluded, and no new ones started. John XXII died in 1334. His successor, Benedict XII, resumed the use of sorcery as a crime of heresy, expanding into small-time practitioners in villages.

In the 14th century, the association between sorcery and heresy took on new dimensions, bringing sorcery and witchcraft into the Inquisition. But nearly 200 years passed before the essential elements of witchcraft as heresy solidified: the Devil ’s pACt, Sabbats, shApe-shIFtIng and mAleFICIA. In 1398, the theological faculty of the University of Paris adopted 28 articles of witchcraft, which became a foundation for subsequent treatises on witchcraft by Demonologists. The articles were considered proof of witchcraft, and they established as fact that a Devil’s pact was necessary for the performance of all acts of magic and witchcraft. The first reference to sabbats in trials occurred in 1475, but sabbats received scant attention until later in the 15th century. Lurid descriptions were given about witches engaging in ritual feasting, sexual orgies and the ritual murder and cannibalism of infants and children.

Devil’s pacts became a central element in the 16th century In the 15th century, the writers of inquisitional handbooks and treatises emphasised sorcery and witchcraft and drew upon the influential writings of St. Thomas Aquinas, who in the late 13th century condemned any kind of invocation of Demons and Devil pacts either implicit or explicit.

The campaigns to stamp out sorcery and witchcraft had the effect of whipping up public fears of the powers of magic. People already lived in fear of bewitchment, and the Inquisition intensified it. Ironically, the attention validated the reality of magic and evil powers.

Most accusations against witches concerning evil spell-casting, but diabolical elements were introduced by inquisitors, who sought to prove Devil worship and pacts in order to convict of heresy. Torture also increased in order to secure the necessary “free confessions” to diabolism.

The witch craze raged for nearly three centuries, from the 1500s to the late 1700s, with the most intense persecutions taking place in the 17th century. In the 18th century, the Inquisition lost momentum and finally came to an end.

The Spanish Inquisition

The Inquisition took its own course in Spain and Portugal, where it was turned primarily against Jews and Muslims, religious sects and even Freemasons. Accusations of witchcraft and sorcery were used against many of the accused. The driving force behind the Spanish Inquisition was political unification of the three dominant kingdoms of Spain, Castile, Aragon and Granada, pursued by king Ferdinand, who ascended the throne of Aragon in 1479, and his wife, Queen Isabella, who ascended the throne of Castile in 1474. In 1478, Pope Sixtus IV authorised the examination of Jewish converts to Christianity. The new royals used this against what they perceived as “the Jewish” problem in their own land.

The Spanish Inquisition operated outside the jurisdiction of Rome and had its own organisation of councils and inquisitors, overseen by an Inquisitor General. As the first Inquisitor General, Torquemada established rules and procedures. Salaries and expenses of inquisitors were paid from the goods and properties confiscated from the accused, so there was great motivation to target heretics.

The typical procedure against an accused heretic was to read accusations against him from anonymous accusers. The wordings were deliberately vague, and the accused was forced to guess the identity of his accusers and why he was targeted. If he guessed wrongly, he was sent back to prison and recalled again. If he guessed correctly, he was asked why the witnesses accused him of heresy. In that way, the accused were manoeuvred into acknowledging guilt and also naming others who might be dragged into court as well. Throughout, the accused was assigned an “advocate,” a sort of public defender, who in actuality did little to defend the accused. Instead, the advocate encouraged the accused to admit guilt.

In many cases, cruel torture was applied. The torture was both physical and psychological. The latter included taking the accused into dark, underground chambers where inquisitors waited with a black-robed and hooded executioner.

Victims were not given formal trials, but rather subjected to long interrogations punctuated by long periods in prison and by torture. Finally the accused was made to appear at an auto-da-fé, at which a sentence was given. The condemned were not always executed; many were sentenced to prison, whippings, scourging, galleys and fines.

Unrepentant or relapsed heretics were sentenced to death by burning at the stake. If they confessed during the auto-da-fé, they were given the mercy of strangulation prior to burning. The executions were spectacular affairs conducted in a public square, attended by royalty. The stakes were about four yards high, with a small board near the top where the condemned were chained. Several final attempts were made to get the condemned to reconcile to Rome. The executions proceeded by first burning the faces of the condemned with flaming furzes attached to poles that were thrust at them. Then dry furzes set about the stakes were set afire.

The Spanish Inquisition did not succumb to the witch craze that swept through Europe, but instead kept most of its focus on religious heretics. The Spaniards extended their Inquisition into the New World, setting up an office in Mexico, whose jurisdiction reached into what later was part of the American Southwest (see SAntA Fe WItChes). The Spanish Inquisition came to a formal end in 1834.

FURTHER READING :

Lea, Henry Charles. The History of the Inquisition in the Middle Ages. New York: macmillan, 1908.———. Materials Toward a History of Witchcraft. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1939.

Taken from : The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca – written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley – Copyright © 1989, 1999, 2008 by Visionary Living, Inc.

http://occult-world.com/witch-trials-witch-hunts/inquisition/

Picture https://www.jw.org

0 notes