#but when it comes to my religious beliefs. suddenly you stop yourself from asserting to me that i shouldnt have a problem woth meat.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The way yall assume the worst about vegans is absolutely tiring. Yeah dude i totally care about inserting my hands into your life and morphing you into the way i think you should be. I totally feel like i need to exert that energy towards you and that you dont have the criticial thinking ability to think about veganism and consider if you truly can or cant. I totally totally care about that dude. Goddamn. Just. so so much.

#and if im vegan for religious reasons would you throw a fit about it?#or is it just when i dont want to hurt animals by eating them that you have an issue?#i dont think im better than you. i just dont want to hurt animals if it can be helped.#if i do that for religious reasons im sure youd leave me alone. probably bc you think whatever i believe in is nonsense anyways.#but suddenly when it becomes about how i dont want to eat animals which would mean killing them for their meat. theres an issue.#why is that do you think?#genuine question#you feel like you can assert to me that no one should care all that much about where their food comes from. unless it effects humans ofc.#(which factory farming does but lets put a pin in that for now)#but when it comes to my religious beliefs. suddenly you stop yourself from asserting to me that i shouldnt have a problem woth meat.#plenty of hindus dont stop themselves. theres a whole debate among hindus about whether ppl should or shouldnt eat meat#you feel like you know enough to lecture me on why ppl shouldnt care when i do it for reasons of not wanting to kill. but i tell you its#for religious reasons and you just walk away?? make it make sense#if you know so much better then counter me on all fronts besides the one you're emotionally invested in#bc youve decided me not eating meat is me judging you for being immoral. so now you're telling at me for just... existing#yelling*#if you feel guilty about killing an animal to eat it then thats on you. im not doing anything hut pointing out that thats whats happeningm#you already know intellectually thats whats happening. we've all known basiclaly our entire lives.#why is it only an issue when i bring up that fact. that we kill them for their meat. does just looking the other way feel better? bc thats#what it seems like.#theres no one i respect least than non vegans who refuse to confront the fact that theyre killing something for their own satisfaction.#non vegans who admit theyre killing for sustenance i have way more respect for. they actually look the action in the face at least#and have made a judgement from actually acknowledging the whole situation.#but non vegans who waft around trying to avoid thinking about how something actually died to provide this food for you-#i have no respect for you.#maybe being thankful before you eat would be a good thing for everyone to do. not towards any god per se but. to at least#acknowledge all the effort and blood that has gone into creating your meal before you. yknow. actually sit w the fact you're eating a cow#or something. not to *make you realize youve been eating meat this whole time and feel guilty*#i genuinely think basic acknowledgement and gratefulness of the source of your food is good for everyone to do in general#and those of us in amercia could REALLY stand to learn how to be grateful about others providing for us.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

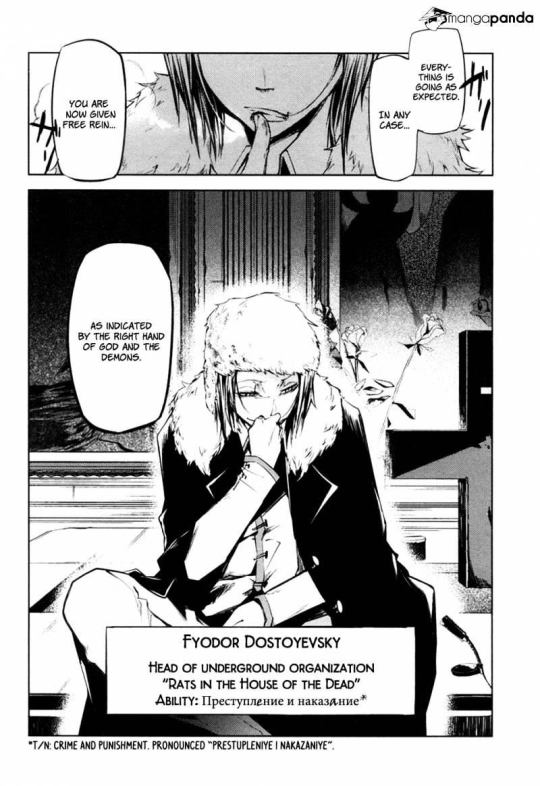

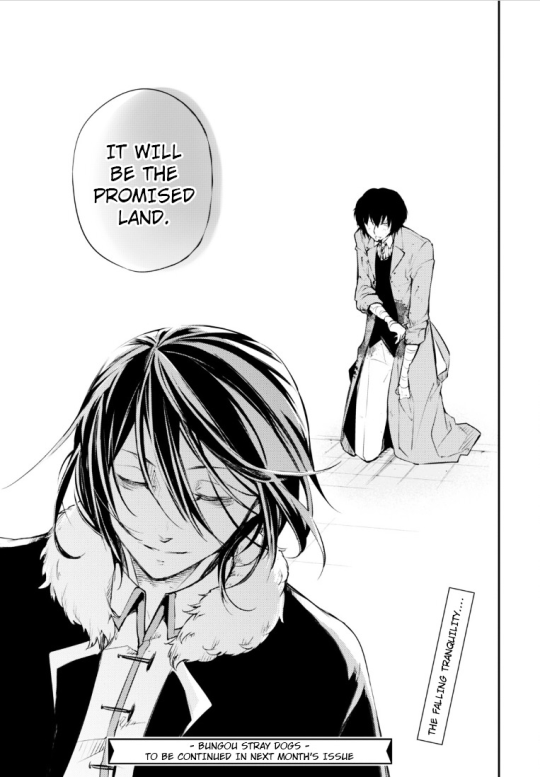

The Man-God: BSD’s Dostoyevsky and Demons’ Kirillov

So, I finally read Bungou Stray Dogs. And y’all, I freaking love this manga. It’s got themes of life, grief, death, trauma, and is chock-full of literary references and puns.

Shocking no one, one of my favorite characters--the reason I started reading the story--is Dostoyevsky, since I’m... rather an admitted fangirl of Dostoyevsky’s novels. I’ve reread each of them at least twice and some (C&P) up to five times. Clearly BSD’s Dostoyevsky not the hopeful, faithful author, but he’s definitely a fascinating antagonist whose arc is digging into the themes of Dostoyevsky the writer’s novels--with a particular focus on the two novels that are my very favorite novels ever written, by anyone, in history: Crime and Punishment and Demons.

But in truth, it draws more from Demons than from Crime and Punishment, right down to having BSD!Dostoyevsky directly quote it.

Demons is far, far less popular that Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov, and even The Idiot, so I was really surprised to see how often it’s been referenced in BSD (The reason it’s less popular is honestly justified: the first 100 pages are paced... horribly, but the rest of the novel is so powerful that I can overlook that). It’s been translated under a variety of titles as well: The Possessed, The Devils, and the most recent is Demons so that’s what we’re going with in this meta.

Pssst--look at how often BSD!Dostoyesvky is associated with demons or devils:

Yet Demons has been popular with literary theorists (one well-known critic has described it as containing “the most harrowing scene in all of fiction,” an assessment I’d agree with--and this is the scene I’m going to discuss in detail) and existentialists like Camus (sorry Camus). Anyways, I have a soft spot for Demons because it contains my very favorite character in existence: Alexei Nilyich Kirillov, who is the character BSD!Dostoyesvky directly quotes.

@blackandwhitemusician did a great analysis of the similar philosophies BSD!Dostoyevsky shares with Crime and Punishment’s Raskolnikov, but I want to talk about how BSD!Dostoyevsky is also modeled after Kirillov’s philosophical ideas. This isn’t to say he embodies them, because Kirillov is decidedly not a villain unlike BSD!Dostoyevsky, but BSD!Dostoyevsky definitely draws heavily from Kirillov’s ideals.

Kirillov is a character who, like Raskolnikov, embodies the contradictions of human nature, but in a hyperbolic way. He's noted to have a "calm but warm and kindly expression"and adores children, playing with them, and he even helps his friend Shatov's wife give birth (he's endearingly awkward and scared for the whole ordeal). He affirms that he is “fond of life” and yet he is determined, from the moment we meet him, to shoot himself as suicide because in doing so he will save himself and the world.

Kirillov’s reasoning is complex and at the same time, spotty, and stems from a deep despair and disgust with human sin. Sound familiar?

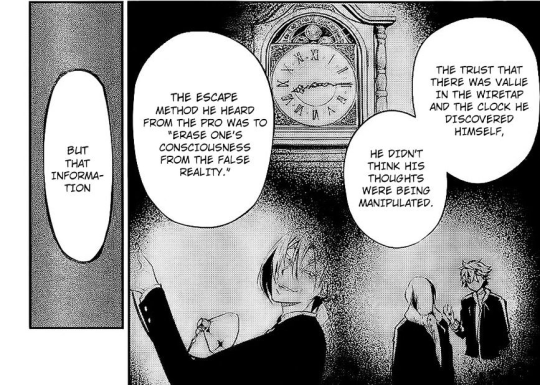

Time is also a major motif with BSD! Dostoyevsky and with Kirilllov. He does not believe in time as more than an “idea.” He insists that “life exists, but death doesn’t at all… [I believe] in eternal life here. There are moments, you reach moments, and time suddenly stands still, and it will become eternal.”

(Clocks constantly appear in BS chapter 42, Dostoyevsky’s introduction, as well.)

Kirillov also draws from other philosophies such as Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am,” affirming that “man is unhappy because he doesn’t know he’s happy… If they knew that it was good for them, it would be good for them, but as long as they don’t know it’s good for them, it will be bad for them. That’s the whole idea, the whole of it… They’ll find out that they’re good and they’ll all become good, every one of them.”

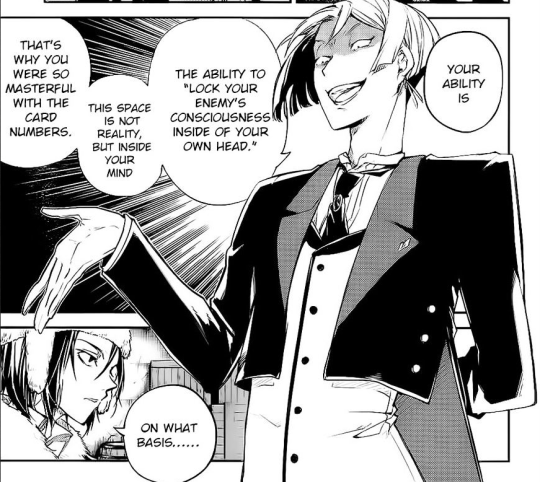

In other words, reality is what Kirillov makes of it in his own mind, which is what BSD!Dostoyevsky hints his ability is (but it isn’t).

It’s still a belief BSD!Dostoyevsky holds: that his beliefs create reality.

Kirillov muses, in conversation with his friend Stavrogin (bold is Kirillov):

“He who teaches that all are good will end the world.”

“He who taught it was crucified.”

“He will come, and his name will be the man-god.”

“The god-man?”

“The man-god. That’s the difference.”

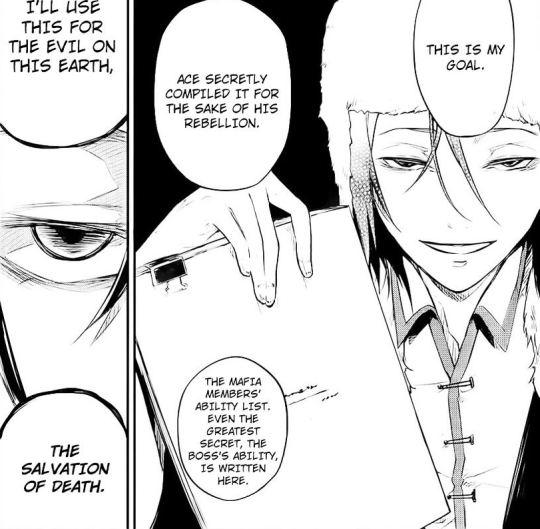

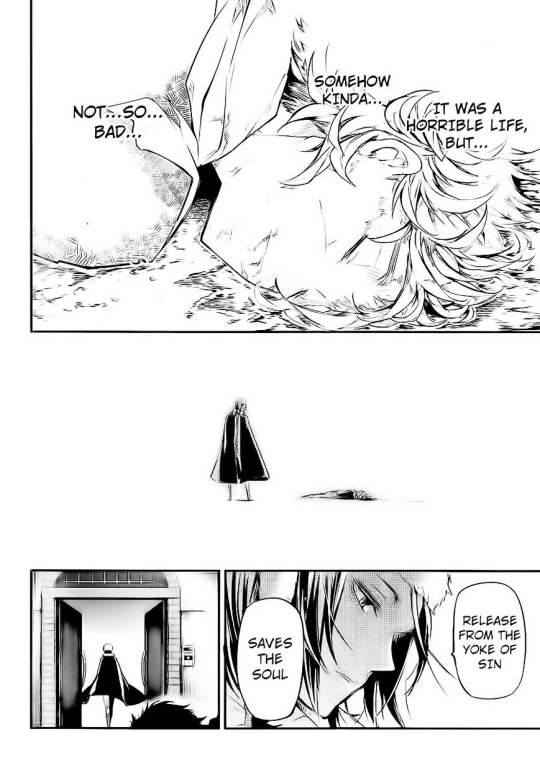

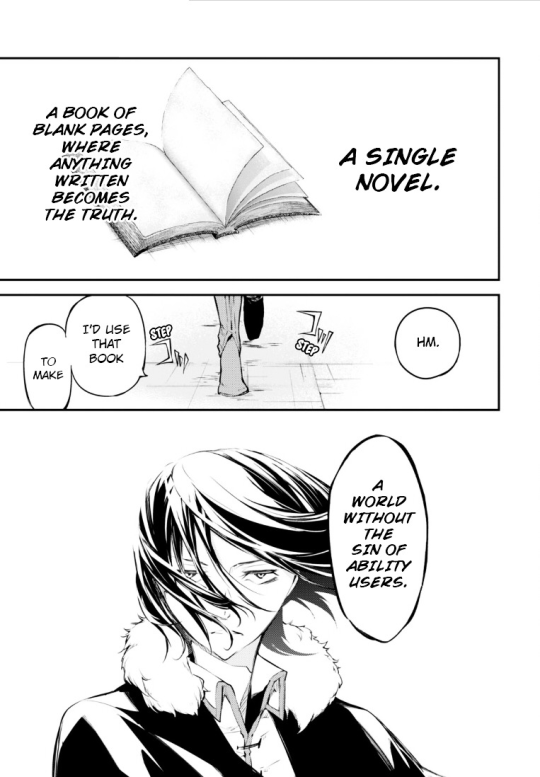

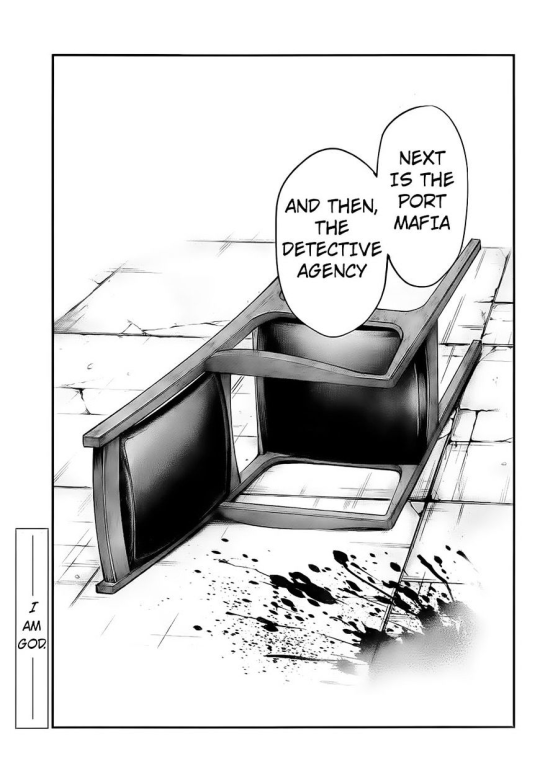

In BSD, anything written in The Book becomes truth, and Dostoyevsky plans to use it to rid the world of the sins of ability-users. Similarly, Kirillov plans to use his decision to set people free, and Pyotr plans to use Kirillov’s mental instability and philosophical suicide to erase consequences for his own sins. And as Kirillov also believes this will make moments heaven, Dostoyevsky expresses (using religious language) that this will make a heavenly reality as well:

As Demons goes on, we find out that Pyotr Stepanovich had struck a deal with Kirillov. Since Kirillov really tries to believe that everyone and everything is good, when Pyotr asks him to kill himself and write a note specifying something Pyotr won’t specify until the time comes, to help Pyotr, Kirillov agrees. Pyotr notes that he doesn’t tell Kirillov what he plans—to have Kirillov take the blame for the murder of their mutual friend Shatov, which Pyotr commits—because he thinks that if Kirillov knows in advance, “Kirillov could not be relied upon.”

The irony, of course, is that by seeking to prove the ultimate will in the universe is of the individual, that the individual is his/her own god, Kirillov becomes an unwitting tool in Pyotr Stepanovich’s terrible plots. He contributes to the unjust death of someone he cares deeply for by taking the blame. And Kirillov did not want this at all. When Pyotr comes to collect, he realizes what he’s done (bold is Kirillov_:

“He is dead!” cried Kirillov, jumping up from the sofa.

“He died at seven o’clock this evening, or rather, at seven o’clock yesterday evening, and now it’s one o’clock.”

“You have killed him!”

…

“You are a strange man, though, Kirillov; you knew yourself that the stupid fellow was bound to end like this. What was there to foresee in that? I made that as plain as possible over and over again. Shatov was meaning to betray us; I was watching him, and it could not be left like that. And you too had instructions to watch him; you told me so yourself three weeks ago.…”

…

“I won’t write that I killed Shatov … and I won’t write anything now. You won’t have a document!”

Pyotr refuses to leave until Kirillov is dead, and Kirillov explains that “I won’t put it off; I want to kill myself now: all are scoundrels.” The exact opposite of what he expressed before about things being good.

"He’s guessed the truth at last! Can you, Kirillov, with your sense, have failed to see till now that all men are alike, that there are none better or worse, only some are stupider, than others, and that if all are scoundrels (which is nonsense, though) there oughtn’t to be any people that are not?”

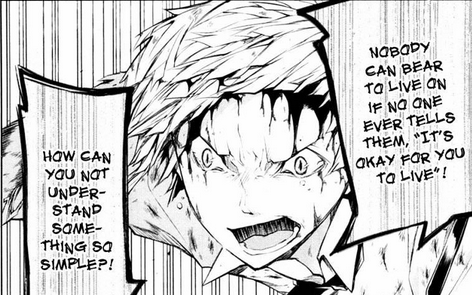

And then we see what motivates Kirillov is a desperate need to have a reason to match his desire to live. It’s literally one of the main themes of Bungo Stray Dogs (bold is Kirillov):

“If you stopped yourself, you become God; that’s it, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I become God.”

…

“Let it be comfort. God is necessary and so must exist… But I know He doesn’t and can’t… Surely you must understand that a man with two such ideas can’t go on living?”

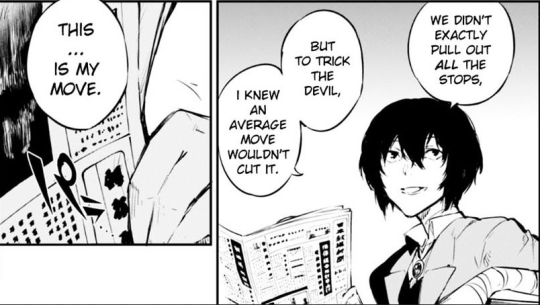

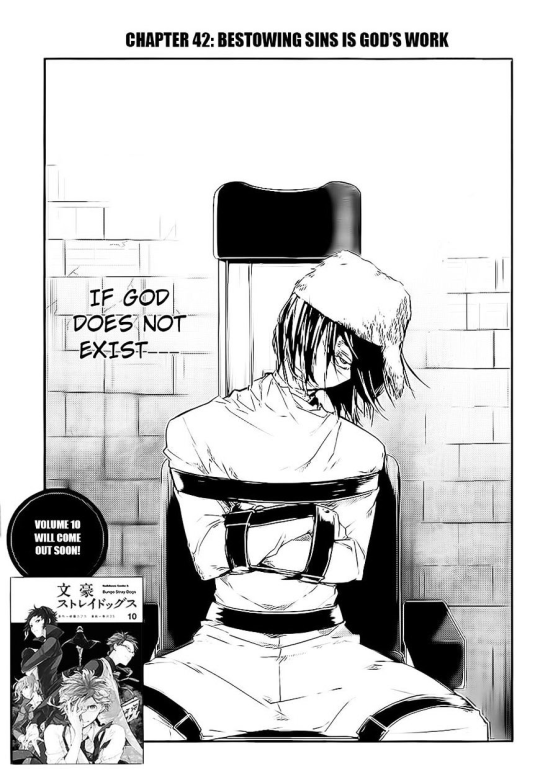

And of course, this is BSD!’s Dostoyevsky in what I am betting is a direct quote from Demons as translated into Japanese: If god does not exist, then I am god.

His man-god belief, like Dostoyevsky’s in BSD, are explained thusly (bold is Kirillov):

“I’ve always been surprised at every one’s going on living,” said Kirillov, not hearing his remark.

...

“Hold your tongue; you won’t understand anything. If there is no God, then I am God.”

“There, I could never understand that point of yours: why are you God?”

“If God exists, all is His will and from His will I cannot escape. If not, it’s all my will and I am bound to show self-will.”

“Self-will? But why are you bound?”

“Because all will has become mine. Can it be that no one in the whole planet, after making an end of God and believing in his own will, will dare to express his self-will on the most vital point? It’s like a beggar inheriting a fortune and being afraid of it and not daring to approach the bag of gold, thinking himself too weak to own it. I want to manifest my self-will. I may be the only one, but I’ll do it.”

That’s a direct quote.

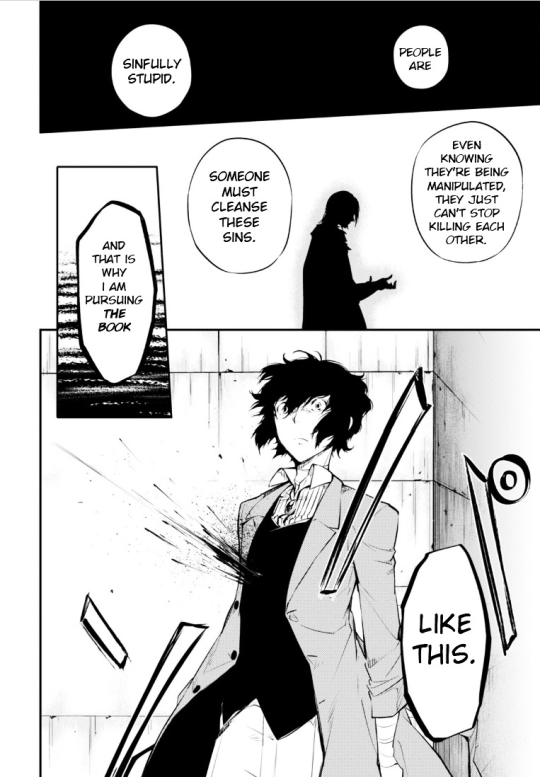

BSD!Dostoyevsky manipulates human will to lead people into committing suicide, and is killing them to create a new world without the sins of ability-users:

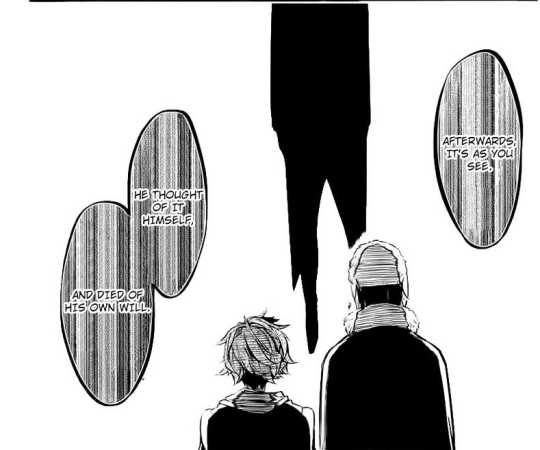

Kirillov says this right before he finally writes the false confession to Stavrogin’s murder and kills himself:

“Man has done nothing but invent God so as to go on living, and not kill himself; that’s the whole of universal history up till now. I am the first one in the whole history of mankind who would not invent God. Let them know it once for all...

“I am awfully unhappy, for I’m awfully afraid. Terror is the curse of man.… But I will assert my will, I am bound to believe that I don’t believe. I will begin and will make an end of it and open the door, and will save. That’s the only thing that will save mankind and will re-create the next generation physically; for with his present physical nature man can’t get on without his former God, I believe. For three years I’ve been seeking for the attribute of my godhead and I’ve found it; the attribute of my godhead is self-will! That’s all I can do to prove in the highest point my independence and my new terrible freedom. For it is very terrible. I am killing myself to prove my independence and my new terrible freedom.”

Yet Kirillov is inventing god: himself. He signs the paper and then does kill himself, but it’s not without the last terrible, terrifying realization that he does not want to die. He wants to live. And he fights Pyotr, biting his finger nearly off, before committing suicide. But Kirillov, as wrong and tragic as his philosophy is, is the one who recognizes the theme of Demons.

“Stavrogin, too, is consumed by an idea,” Kirillov said gloomily, pacing up and down the room.

The point of the entire tragedy in Demons is basically if you are consumed by an idea, it will turn you into a devil. Kirillov is, along with Shatov, perhaps the most likeable main character in Demons (others are far more horrifying as their various political, religious, and philosophical ideas take them over). And so is Dostoyevsky in BSD: consumed by his ideas, convinced his will is all that matters.

It won’t end well.

#bsd meta#bsd#bungou stray dogs meta#fyodor dostoyevsky#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#alexei kirillov#demons#the possessed#the devils#philosophy#bungou stray dogs#osami dazai#suicide tw

610 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear cis friends who are dying to get my perspective on the latest trans story you heard in the news:

Before you read further, please know that I applaud your curiosity and your attempt to be aware of trans issues in the media.

But.

But, just because your friend is trans doesn't mean that she's qualified to answer (or interested in doing so for that matter) any trans-related question you may have. Especially on topics which are hot in the news - the reason so many trans topics are in the news and coming to your attention is because we are being targeted and used as a wedge issue by conservative and far-right groups in an effort to gin up energy and excitement to get their voters to the polls.

After they lost big on the same-sex marriage equality issue, they turned their attention to a more vulnerable and less protected group and began aiming all of their attention, marketing budgets and legislative resources squarely at us.

Since 2015, we have seen bills trying to keep us out of public bathrooms and locker rooms, bill after bill targeting our access to healthcare, identification, name change processes and court case after court case trying to enshrine the right to discriminate against us in housing, employment and public life based on someone else's religious beliefs and, of course, an administration that seems to be specifically trying to erase us from public existence and public service.

All of this is helped along through their friends in the media "just asking questions" - ones that usually have nuanced and complex (but not difficult to understand) answers. Which they don't care about, of course, because asking the question is enough.

The goal is to get you to ask these questions, too. And just the asking puts enough cognitive distance between you, a cis person, and trans people to create the "otherness" in your mind that they can use to justify our continued dehumanization. It also forces us to repeatedly have these same conversations, over and over and over again.

I have answered the exact same questions over and over again for old high school or college classmates, coworkers, random internet acquaintances, who heard someone talking about an issue they have never cared about before, but suddenly need to know the answers to.

Lately, for example, it's been trans teen athletes. Before that it was trans people in bathrooms and locker rooms and why trans people want to serve in the military and why employers shouldn't be able to let an employee up for wanting to transition.

Most of the time, I put in the work to answer those questions because I know you all mean well. And you want to know the answers to what sound like very reasonable questions and you're trying to be good allies.

Each one tied me up for days with follow-up after follow-up after follow-up. And tired me out because I had to do all the research they could have done, but chose not to do, to become at least a middling expert so that they were satisfied with hearing the answers from the one trans person they knew, instead of reading the numerous articles from actual experts and actual trans experts who have already been writing about this since this particular boil began to fester on the general public's collective posterior.

Did you stop to ask yourself why you thought I might have, given my current life circumstances, any valuable knowledge about trans teenage athletes, let alone the finer points of high school athletics regulations? Or whether I've done any research about two specific trans teenaged athletes halfway across the country from her, who happen to be the media's bugbear and the target of a lawsuit from cis competitors? Other than the fact that I'm the one trans person you know?

For the record, trans women do not have any special advantage over cis women, under most current regulation schema. Do you think that it's possible that the high school athletics organization which regulates those two particular athletes are completely unaware of their existence and are simply waiting on enough curious cis people to "just ask reasonable questions" before they consult the science and those girls' specific situation?

Have you considered how many trans athletes must exist and how you're only hearing about a handful of specific trans teen athletes who happen to be winning. Are you not concerned about trans athletes as long as they have the decency to lose to their cis competition?

Trans people have been allowed to compete in the Olympics since 2002 (I believe). Do you want to guess how many trans people have even qualified for the Olympics? Exactly 1, maybe. One trans man qualified, just last month, to try to make the Olympic team this summer. Zero trans women in *ANY* Olympic event have ever qualified. Ever.

And trans people are not new to athletics. We've competed in just about any event you can imagine.

I might be the only trans person you know, but you are not the only curious cis person I know. Consider that before deciding that my specific perspective is required for you to find some way to be comfortable learning that other trans people exist in situations you didn't previously know, think, or, frankly, care about before now.

Please understand that it is a terrifying and exhausting time to be a trans person in this society. We have an enormous target on our backs. None of that is helped by our cis friends asking us to help justify, identify and isolate the pockets of public life where it's reasonable to exclude us and discriminate against us.

We are roughly 1% of the population. Roughly equivalent to natural redheads. There's zero conversations about how natural redheads higher pain tolerance might give them some kind of athletic advantage over their competition in endurance sports.

But then, there's also no well-financed movement trying to legislatively, morally and socially ensure that you see them as a lesser form of human so that they can hold onto their political power.

When you see these stories, and your curiosity starts to churn, ask yourself these questions before you reach out to your trans friends:

1. What is this article/story/column trying to make me feel about trans people?

2. Does it rely on treating trans people as an "other"/less than human/oppressive in order to make me feel that?

3. Does it actually provide information, an opposing view and sources for its assertions or is it relying on your lack of knowledgeand expertise to create an emotional reaction?

4. Is there another article on this topic that might have more information? Has someone written a response to this article (often found by googling the headline)?

5. Does this article/story/column quote from a trans person who is not the target of the article (i.e. an expert source, not the subject of the article)? Does it even contain a quote from the subject of the article or only from those who oppose them? What have other trans people said about this story?

6. Is the writer a reliable journalist or columnist? What is the bias of the publication/media source?

7. Who benefits from this being in the media right now?

8. What emotional impact will this have on my trans friend if I ask her about it without thinking about any of these previous questions?

Please continue to feel free to ask me your questions about transness, but also please try to ask Google first, especially if it's about a news article about some new fun way that trans people are being targeted, or cis people finding novel ways to feel oppressed by our audacity to exist near them.

Please take some time to consider what emotional impact it might have on me to hold your hand through another conversation that requires me to defend the humanity and dignity of trans people. Don't ask me to make you feel comfortable with discrimination against trans people, no matter how reasonable it sounds.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOYAH ON BBC RADIO 4 “ONLY ARTISTS” WITH ALICE LOWE 7.3.2018

ALICE: I'm Alice Lowe. I'm a writer, actor, director and I'm going to meet Toyah Willcox. Toyah is someone who I feel has always been there. I remember singing her song “It's A Mystery" in the playground and as I got older I followed her career and was astonished at someone who managed to be so creative and inventive in several different fields. So she's always held a massive fascination for me, and now I'm going to meet her. ALICE: (talking about theatre) When I go to see something when nothing really happens, I'm like . . . I can't give up an evening for this. I need some spectacles. TOYAH: I always hit the theatres that have the most fantastic sets. Because I just want that rush when it starts changing shape. ALICE: I feel that a lot of my work comes from the power of the individual. It's about one person and their kind of struggle to assert their individual power or beliefs or will. That's what astonishes me about your career. How you sort of went "Oh, I've got to get myself into a band" and it was like that just happened and you must have had such clarity of focus?

TOYAH: The first five years of my career was as if my guardian angel’s in the room with me the whole time. Just blessing after blessing, it was extraordinary. I knew I had to get out of Birmingham at that particular time, which is where I was born and get to London, which is where you had to be to make things happen at that particular time. I followed David Bowie so religiously, who was around in the 70’s obviously, which is when I was a teenager and I observed how he changed. He was a chameleon and I saw that as a really ideal way of reinventing myself. I didn't like who and what I was. I didn't feel that I was born as a particular beauty where beauty would get me through the open door. I knew I had obstacles and I also realised I had to be different, so I made myself different. But I think the irony there is I actually was different. It was going to happen anyway. I got spotted walking down the street in Birmingham when I was at drama school. That ended up me being auditioned for half an hour play on BBC Two. I got the job. Then that was watched by Kate Nelligan and Maximilian Schell on TV when it went out on BBC Two. I was invited to join the National Theatre where Maximilian Schell was making his directorial debut. And that led to me forming the band. It was just a chain reaction.

ALICE: But you're talking about it almost like it happened by itself. It had to be something coming out of you that people saw that they just knew that you were right for the part or that you had this focus about you? TOYAH: No one had any faith I was capable of doing anything. I was not academic at school. I didn't fit in at school. I didn't want to be there. I did not feel I belonged in my family or at the school. I felt completely different generational attitudes, so everything I did I kind of did to prove myself I could do it. But also to prove to others I could do it. Every success I had took everyone by surprise and no one ever gave me any encouragement whatsoever. No encouragement, no support. (Alice laughs) They just wanted to know how much was I earning. It was as simple as that. ALICE: Well, I think I have a slightly similar thing because I think my mum and dad would have liked it if I'd been an RSC (Royal Shakespeare Company) actress. To me it's incredibly freeing when you do something in your own way, and it’s successful and people are like . . . "oh . . . ".

I remember at school playing badminton and I was quite good at badminton and I won a little mini tournament and then the sports teacher came to me and sort of went “you holding the racket all wrong. You need to do it like this”. Suddenly I was rubbish at badminton and they took that away from me! TOYAH: Your way works. ALICE: I don't know why it works, it's not the right way. TOYAH: Also I believe our instinctive voice, that very first voice that comes into your head, is the one that's right. Especially when I'm writing a song or I'm approaching the scene. The first voice in my head is the right choice, and if you over intellectualise or even over introduce technique into something - you've taken away your ability to play the badminton, as it were

ALICE: Yeah. I don't know why it works or why it doesn't work. It's like if you say "pull it apart" . . . I can't put it back together again. Sometimes I'm in the middle of rewrites now and it is a constant negotiation because when you do rewrites it is a cerebral task. You are fixing stuff that doesn't work. Whereas the writing of it initially is an instinctive thing, and so it's a constant negotiation of how not to kill that beautiful little flower that blossomed but still have it working as a script. So I always find that really painful, the rewrites, because I never quite know whether I'm throwing the baby out with the bath water . . . TOYAH: When I'm writing, mainly songs, I have to dance and if the track doesn't make me dance or cry, I know I'm not in the right area. ALICE: That’s interesting, yeah … TOYAH: Sometimes I cry out of the pure joy of discovering something. And you start to kind of have an adrenaline rush, but if I can dance then . . . I don't know . . . The lyrics are more interesting that come from movement.

ALICE: Similarly, when I'm writing screenplays, I listen to music. Then if I feel I've lost a bit of the soul of the meaning of the script, I go back to the song I need for that scene and that helps me to access that emotion TOYAH: That’s fantastic. I’ve never thought of doing that. ALICE: It helps me to write in a more intuitive way. Actually reminds me of a clip that I watched with you and Sir Laurence Olivier (below with Toyah) and what I thought was amazing is obviously he is incredibly charismatic, but when you spoke you had this freshness to you that was so real that you were like a real person meeting the actor Laurence Olivier. And I like naive fresh performances. Is that something that you had a grip on even at that age?

TOYAH: It's what I had when I worked with Olivier on the “Ebony Tower”. I've just come out of a London run of “Trafford Tanzi”, which was a huge critical and commercial success. It kept the Mermaid Theatre open for six months, and the nature of that performance was very northern theatre. Very real, very gritty, just throwing lines, throwing improvisations. And then I go into the “Ebony Tower”. Written by John Fowles, which is quite a sturdy script. With Olivier - who was very poorly at the time, he was only about four years away from passing away when I worked with him - but utterly adorable and totally committed. He was only allowed to work three hours a day, which meant that our work with him was very focused. We would rehearse on camera without him being there, and then we'd bring him in. So a lot of that pace was the pace of Olivier, where he was at that time in his life, but also the pace of an actor who had always savoured every line as an actor. And here I was a kind of performer that's always been thrown in the deep end and was waving not drowning. So it was like a meeting of two different energies. And I think my freshness with him was not wanting to overstep the mark

ALICE: And you actually said something in an interview with Terry Wogan or somebody, they said “what did you learn from him?” and you said, “well, I didn't really learn from him because we're both from completely different schools of acting”. TOYAH: I couldn't learn anything of him, but what I did learn is that spirit of adventure never dies. He was the same spirit that he was when he was forming the National Theatre or starring in “Hamlet” as he was as a dying man. That spirit was just as vital and just as powerful, the flame was just as bright and that kind of taught me never to give up and never to stop pushing against the resistance you constantly feel when you want to be different. ALICE: I remember in the playground people singing “It’s A Mystery” and doing impressions. You've just been there my whole life basically. And it was only later, maybe when I was a teenager, and when mum and dad said “you should watch this Derek Jarman thing”. TOYAH: Oh, cool!

ALICE: And then I’m like how is this person the same person?! They’ve done this and they've done this and I think probably you're one of those people that for me made me go it is possible to invent yourself. He must have been a mentor figure for you, Derek Jarman, because you worked with him on more than one occasion? TOYAH: He was great. I didn't know what I was dealing with. I was a complete innocent. I was 18 years old at the National Theatre. Ian Charleson was in another production. Lovely man and he grabbed my hand one day and he said "you have to meet this friend of mine, Derek Jarman. You've got a lot in common". So we went along to Derek Jarman's flat to have tea. And Jarman just pointed to a script, which at the time I think was called “Down With The Queen” and he said “this is a film I’m making. Choose a part” and it's about a girl gang who rape and murder men and it's a punk movie. The first ever punk movie to be ever made. So I looked through the script and was instantly attracted to “Mad”, the pyromaniac. And he said “yeah, the role is yours”.

I almost didn't get to make the film because Derek had the budget cut a few weeks later and he had to lose characters and he was going to cut “Mad” out of the story. He realised when he told me this that I was just broken, I was so looking forward to doing this but he forsook his fee so that I could go back in the film. It was the first movie I ever made and it is influential and it's a bonkers film. It's a collage of madness and now, today, 40 years on, it's quite interesting taking something that was my very first movie into the theatre. I’m are not playing “Mad” obviously. I'm playing Queen Elizabeth I (below), who is transported into the present day to see the results and the consequences of her law. And here I am, this grand old woman playing Elizabeth I in the punk play with the most fantastic, brilliant activist actors and again, I'm finding myself being re-educated into the present. And it's a pattern I found all my life that my best work has come out of having to learn everything I thought I knew. To relearn and learn again with a new attitude.

ALICE: You actually have to never really just go “you can have a glass of champagne, maybe at the premiere. Back to work” (laughs) TOYAH: Yes, there’s always a price to pay. ALICE: This is why I'm here Toyah, to ask your advice. How do you juggle these things? TOYAH: You've got a child. How old is your . . . ? ALICE: Two TOYAH: So the dreadful two’s . . . You cannot give yourself any time at this moment, but it's possible you put away that extra hour in the morning if you can bear it. If you've had a good night sleep and you make sure you do 1000 – 3000 thousand words a day. Here am I telling you what to do - I have exactly the same problem as you.

ALICE: It’s interesting. It’s that thing isn't it, because I had a friend recently ask “how do I write with a baby?” and I said “Della has a 2 hour nap in the afternoon and that's how I've got my screenplay done” and I had so many people going “you've written a screenplay in two hours in an afternoon?!" I was like “well, it's all I've got!” When else am I going to do it? I mean to me work isn't work to me. It's just me. I'm happy when I'm making stuff. But I think people find that stranger from a woman than they would from a man sometimes. TOYAH: Why do you think that is? ALICE: I don't know. Is it just gender? I think it's interesting that people often say “do you love your work?” or whatever, and you wouldn't be asked that question if you're a man. The other thing that people can easily think is that it's a vanity project for you if you're a woman. That somehow you want more attention for yourself

TOYAH: I find that extraordinary that people think you do what you do for attention. It's a vocabulary. It's a language. It's a need. My husband and I - he's a musician so we have a lot in common. We think like creatives, and when we're not allowed to be part of that process, we feel as though we're dying inside ALICE: And I think any creative differences that I've had in the past is because people have not understood that that's the way that I feel, where they're like “why are you giving an opinion about this? Why do you care about this? Are you worried about your hair? Are you worried about this? Are you worried about that?” and you go I just care about the word. I'm like you. You know how you want this to be good? I also want it to be good and it's quite incredible how people can misplace your agenda. And I do think that it would be very unusual for someone to say to your husband “why do you play the guitar? Do you like the attention?” TOYAH: It just wouldn't happen. ALICE: "What do you want from it? Is it because you want fame?"

TOYAH: I find it quite extraordinary and it fascinates me because what I specialise is ideas. But I want those ideas to have a life, they're nothing to do with me needing attention or being needy or expectation that I'm going to be glorified and awarded for it. It's the way I live. I have an idea. Therefore, I believe that idea has a place somewhere in this world. ALICE: I think we are similar in that I have ideas and they torture me at night and I don't know how I'm going to make the idea because it might be an opera. I'm not an opera singer and or an opera director but you know what I mean? I suddenly have this idea and I have to find an outlet for it. Do you feel like you're torn about how to express that idea? How do you get it out there? What medium are you going to use? Because you do so many different things

TOYAH: Well, initially I'm torn because of lack of technical ability. I’m very instinctive. I'm dyslexic, but my ideas are very clear and very sharp and I surround myself with people who understand what I'm trying to say. It is frustrating, but I have limitations and I think one of the reasons I do so much as I work within my limitations. I can only go so far as a musician. I'd love to go further as an actress, but I think part of my problem as an actress - and they’re good problems to have because I'm doing at least five movies a year and “Jubilee” the stage play at the moment - is I’m very small. (Alice laughs) I have a very distinct sound and I have a very distinct energy which is related to Toyah and that limits how people - ALICE: I think it limits you, but it's a good limit. As you say, you can't do everything. I had that when I was younger “why am I not getting more roles and stuff?” And then I realised actually I'm a niche. I'm a character actress so the roles I get are the ones that are right for me and again that some of the actors that I admire, someone like Bill Murray or Donald Sutherland . . . they're always themselves.

The older I've got I've sort of gone actually, it's important to give yourself as an actor. You might be playing lots of different roles, wearing lots of different wigs or whatever but essentially, it's a generous act to give yourself and the more you give yourself the more it touches the audience and the more powerful it is, and that vulnerability is key really TOYAH: That's a unique thing about film though, isn't it, it knows that truth? ALICE: Yeah, the camera is very sensitive, so it's going to pick up anything. And I think this is when I realised that I was going to go more into film acting as well. My facial expressions are very tiny, but sometimes people say “you're dead pan”. I find that I am but I am doing stuff as well. TOYAH: You don't want an animated face like my mine. Mine’s pogoing all over the screen (Alice laughs)

ALICE: I also think this is another thing with men and women as well. We're used to seeing women like emotional geysers so the value that we give to screen sometimes is like “she’s going to cry!”. It's going to be brilliant. That's the money shot. We need tears from this woman. She's going to pull faces and look upset.” And then you've got Clint Eastwood just twitching his eye. And apparently that's an amazing performance, you know? Well, it is, but there is room for women to internalise everything, everything they're feeling, everything they're trying to hide, which is actually what most people are doing in their day to day life all the time. We want to hide our emotions and our feelings. TOYAH: About eight years ago I was cast as Billy Piper's mother in “Diary Of A Call Girl” and I'm used to bravado acting. Billie Piper on camera gives very little when you're in the room with her. And yet she is telling you everything you need to know when you see it on camera and that is something I am desperate to learn. Out of every performer I've ever worked with she's the one person that could teach me something. And it was how to take it right down. Internalise it but allow the audience to see enough. ALICE: There are people that can do that. I've worked with a lot of men where you just say “are they doing anything at all? Are they doing anything?" You see them on screen and you’re like . . . oh my God - they’re a genius (laughs)

TOYAH: I did “Cluedo” (1990) (below, Toyah with co-star Kate O'Mara) with Sean Pertwee and (in a nasal 50’s movie voice) there I was acting away being this tart Miss Scarlett and Sean was giving me nothing back and when I saw the edited version he was fabulous! Charismatic! Brilliant.

ALICE: But some people they know when their close-up is basically technically . . . “I’m going to do it at this level and then I know this is where I’m going to really deliver”. I think I'm guilty of that myself because I get scared. I'm going to be one of those people and say that. I can be quite shy. I can be a complete mixture. I can be like, yeah, I'm really confident! And then the next minute . . . oh no, I'm scared. I don’t want to do it. I’m gone. So sometimes, like in the rehearsal, I am holding back. I remember a director in a comedy saying to me after we shot this scene “that’s the best you've ever done it" and I was a bit like “well, I wasn't going to do it the best I've ever done in rehearsal”. TOYAH: I totally agree ALICE: For me, and when it's an organic thing, you know someone like Sir Laurence Olivier, I think because of his training in theatre and also the way that film stock was, you had to be spot on with every single take. I'm not like that. I don't know what I'm going to really do and that's the joy of working with digital as you can just do it in 20 different ways. That's going to come out and just film it, and if it's awful, it doesn't matter. We'll go again. If it's really scary and weird, that might be the tape, but I might not be able to do that again.

TOYAH: I agree. And also talking about improvisation because it's something very important when creating new songs. When I've hit something, I've hit the right note, I've hit the right theme - you go into a state of superconsciousness and you feel that's why I'm born. That's why I'm here because it's a level of consciousness you can't get in the normal daily day routine. And some songs can take weeks to finish, but the ones that have the most success take two minutes to write. And you're just in this state and you don't know where the energy is coming from and you're so alert. If you were being chased by a bear, you'd outrun the bear because of the energy. You're going to explode! ALICE: (laughs) Just fly through the air. TOYAH: Yeah!

ALICE: I know exactly what you mean. I kind of think that's what happened with ���Prevenge” (film, 2016) that I was in the middle of. To me it was a really strange experience which was pregnancy - TOYAH: Probably not the best time to make a film! ALICE: You say that, but actually I felt this kind of incredible creativity, and I also felt an out of body experience like something is happening to me that I don't have any control over and in a way that narrative is taking control of me. So it's writing itself. It felt very obvious, all the choices, just easy and you long to be in that state. But the thing is, I think you kind of need the six weeks writing the other songs to get to that point. TOYAH: Yeah, definitely agree. When I wrote “Anthem”, which is the first platinum album we had as a band - I was 23 going on 24. That took all those years of experience to write that album and then I had to write the next album within 12 months and I've been touring and doing 14 interviews a day and the ideas haven't had time to percolate. That said, the next album was “The Changeling”, which I now think is probably one of the most important albums of my whole career, but it's bleak and it's bleak because I felt so trapped and under pressure

ALICE: There is one amazing image that I love. I've got it on my bookshelf with you with sort of seagulls painted across your head TOYAH: “Brave New World” ALICE: Oh, I love that. And the dark contact lenses. I mean, who was really doing that kind of thing? TOYAH: I kind of nicked that off Steve Strange (they both laugh) (below with Toyah) I think he had those in for Bowie's “Ashes To Ashes” video and I just thought they were so cool and so fantastic.

ALICE: But how many women were really playing with that kind of imagery? I mean, it was a maybe a particular point in time, like the early 80’s where there was a lot of influx. Wasn't there? Punk had happened but everyone knew something huge was going to come TOYAH: Every year I'd say, not only every year, but possibly every three months the movement developed it, evolved it, it moved on, and everyone went with it. And I think singers like myself, Siouxsie Sioux, Hazel O'Connor, Kate Bush, Kim Wilde - we really persevered and we were pushing the glass ceiling up. But each year of the 1980’s is defined so much by a different fashion, a different sound in music . . . It's not one decade. It's 10 years. ALICE: Yeah, hopefully that stuff is coming back. I think that because people do want spectacle and they do want creativity and they do want to be snapped out of the mundanity of existence. And the loss of Bowie and Prince, really like magical beings in our own realm, basically

TOYAH: I’m optimistic that it will happen because when you look at ticket prices across the board they’re really expensive for a family to go out, it's almost impossible. And I think that these creatives will come forward that will start in the small clubs again. Even in the pub circuit, because I was successful because I toured pubs. My band were drawing 2000 people per night into a pub and the town would shut down wherever I played. And the ticket price I think was probably 6 shillings or something ridiculous. I think if show business keeps pricing the audience out of the experience, then something will happen that will allow the creatives kind of back in. ALICE: It's almost like we need to have some sort of apocalyptic event so that we're all just sitting in tents with hand puppets and telling each other . . . (cracks up laughing) TOYAH: Passing the news on by storytelling again. Simple. ALICE: The innocence of being easily impressed by something

TOYAH: I've experienced that watching shows myself. Watching ballet, even watching “The Nutcracker” every Christmas. It transforms you. It changes your own self perception. And I think that's what creativity and performance is about and I think when you create something, it's like a light bulb going off. When I first really listened to David Bowie's “Life On Mars" - it was after I'd heard “Star Man” and fallen in love with a man. But “Life On Mars” transformed my identity. My idea of what I should be doing with my own life and what was possible out of the creative act of songwriting. ALICE: It’s interesting becauce that's my favourite David Bowie song, “Life On Mars”. There’s something so incredible about that as a piece of music. TOYAH: It's almost about the hopelessness of the violence of life for me. “It's a God awful small affair to the girl with the mousy hair”. Well, the girl is tragic. She's got mousy hair, apparently, and then there’s a fight in the dancehall, and it's all about the hopelessness of us needing Saturday night celebration to let off steam. But really, all we end up doing is kicking the shit out of each other. But it's so beautifully observed, and it's so real, and it's so Hollywood glamour and yet gutter level violent and it is a clever song.

ALICE: Do you think we listen to it and think it's our life story? You were talking about the lyrics - I was that girl with the mousy hair. Me looking at the screen and going that would be nice. I mean it's not even about fame, it's about escapism. So people would say to me, especially when I was younger “why do you want to be an actress? You want to be famous?” and I was like “no. I want to be a mermaid. I actually want to be a mermaid”. Yeah, that's the thing. I don't want the in between but the acting bit - that's just a means to an end. I actually want to be something else. That element of fantasy is really what I tried to get on camera and I get to that point where the lack of self consciousness . . . don't cerebralise. Just be.

Alice with Toyah at her Chiswick flat

You can listen to the discussion HERE

#toyah#toyah willcox#toyahwillcox#toyah radio#toyahradio#toyahbbc#toyah bbc#toyah 2018#toyah2018#thetoyahwillcoxinterviewarchive#the toyah willcox interview archive#toyah interview#toyahinterview

0 notes