#but the theory is there working beneath the text. i didn't want to scare anyone with the whole academic stuff

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

If we are to take a deep dive, it is best to assure the place we're leaping from is stable, so let's do that by starting with the obvious.

The subject in both of these sentences is the same: the Halo. Both of these characters have borne it. Both sentences present the same grammatical structure and answer directly to one another despite the distance in time and space between one and the other's utterances. To Ava, the receiver of these conflicting messages, both claims prove themselves to be ultimately true, for the Halo acts as a gift, in granting her a second chance at a life she never had, and also as a burden, as it imposes on her responsibilities and demands of her sacrifices she would otherwise have never known.

But the show itself openly invites us to dig deeper, so we should not be contented with the obvious alone.

If there is always more, then we must peel back the surface and peek at what is underneath if we are to grasp at least a fraction of the functioning of Warrior Nun in different levels—be it in small scale, pertaining to the characters themselves, or be it in large scale, including how all of it relates to us as viewers in the end.

These two moments of season one are but a fragment of the show’s comprehensive universe, but we will examine them closely to see just how much meaning we can find in them, deceptively simple as they seem.

As mentioned above, the grammatical structure of both sentences is shared between them: “the [subject] is a [noun]”. This could lead to some sort of direct description we associate with the act of definition, of explaining what something is, as in “the pope is a man” or, to use the same reference as Mother Superion and Shannon do, “the Halo is an object”. In fact, had this been the case, we would have been closer to Ava’s own conclusion of the Halo being “a hunk of magic metal embedded in [her] back”, as this is a characteristic anyone could ascribe to it upon examination.

Yet the words used by both former warrior nuns are “gift” and “burden”. If they describe the Halo, then it is not in terms derived from objectively observable traits it possesses (such as it being made of metal), but in a wholly subjective manner. When Mother Superion and Shannon say the Halo is this or that, both imply that it is this or that as relates to themselves. In relaying what the Halo supposedly “is” to Ava, they pre-interpret it for her, infusing it with their own points of view—their beliefs. What they say of the Halo is much more a reflection of who they are than anything the Halo in itself could be.

A) The gift

A gift is, as we know, a present. It presupposes a giver and a receiver, as well as some degree of gratitude on the part of the latter, even if justified by politeness alone.

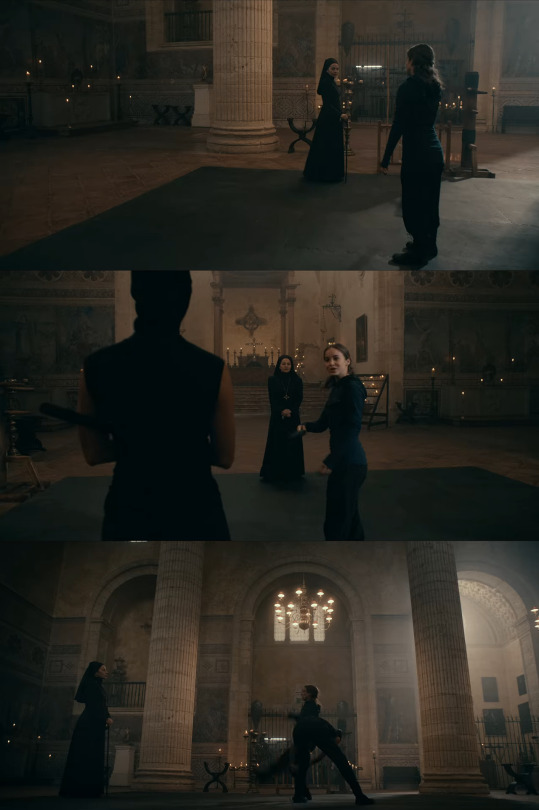

Mother Superion, embodying the authority of the Catholic church, framed by candles and an altar behind her while making use of short, straightforward affirmations, does not need to clearly state who occupies these positions: we can safely infer that the giver here is God and the beneficiary of this divine benevolence is Ava. A definiteness is patent in the sentences that follow—here is the power of the institution at work, for if Mother Superion starts out by “defining” the Halo, now she defines Ava through it. An inversion takes place, as the woman allows the object to define the woman (as “God’s champion” who “fights in His name”) rather than the other way around. The church, the Halo construct Ava as a subject, subjecting her to certain ideas of what she should be. She is the warrior nun despite having no say in it, not being a warrior and much less a nun.

At first sight, it wouldn’t make sense to interact with Ava in these terms, especially if, by this scene, Mother Superion has already read her file. It wouldn’t be difficult to deduce how expressions crafted with religious colours might impact an audience that does not show any religious proclivities. Furthermore, the tradition of rhetoric has always taught that speakers ought to adapt to their listeners if they wish to get their point across, so either Mother Superion is incompetent at communication, lacking sensibility and skills, or she is making a calculated move—one that is fully supported by her hierarchical position. After all, superiors seldom need to rationally convince their subordinates of doing something given how the latter are compelled instead by power dynamics to get in line—or else.

The strategy doesn’t really work on Ava.

In semiotic terms, we could even argue that there is something confusing happening in this scene—a narrative phase of manipulation (wherein someone tries to get someone else to accept and do something), we could say that it contains hints of both seduction (a positive commentary on the interlocutor—it’s not just about anyone who can be god’s champion, so this is a positive distinction) and intimidation (the threat of negative consequences if the interlocutor doesn’t comply—there is an implied order in the sequence, meaning Ava cannot refuse to be “God’s champion”). Ava might not share in this world-view, but it is what the church and its followers propose: a gift from God is a positive value. Being chosen by God to do something, even fighting and possibly dying in the process, is a positive value. Lilith is standing right there beside them and, at this point, she would surely agree and see nothing of this exchange in a negative light.

Yet Ava isn’t a nun and indeed she does not perceive any of these “honours” as being desirable. Mother Superion’s stance, the image she presents of herself as a strict nun herself when Ava has been mistreated by them all her life, equally gives her no reason to be persuaded, much on the contrary.

The manipulation fails. Ava is told God gave her the gift of life… And that now she is to endanger and potentially lose that very same life as some sort of gesture of gratitude. The logic is unimpressive at best and frankly absurd at worst.

Within the framework of the church, however, it makes perfect sense. Misattributed and misconstrued as it might be, the motto of credo quia absurdum is still pertinent: “I believe because it is absurd”. That a god should grant life only to claim it back through violence is perfectly acceptable if one believes in this god’s unquestionable authority rather than seeing this demand as something ridiculous or cruel.

The very concepts of God, service, battle, duty, blessings only make sense to the faithful, something Ava isn’t. She’s just a puny little individual resisting the pressures brought upon her by a powerful institution.

She and Mother Superion are only speaking over one another, not really having a conversation; Ava doesn’t care to listen to what the church has to say, she doesn’t take it seriously, and the church likewise does not take her individuality, her person into consideration.

However, we would do well to remember that Mother Superion is not simply a mouthpiece for the church—she is also Suzanne, lowly little individual with lowly individual desires and resentment just as Ava.

And, regardless of the effacement of self that monastic as well as military institutions enforce on their members, just as Ava’s subjectivity isn’t neatly negated by direct statements in line with reigning dogma, Suzanne’s own subjectivity also seeps through her words and attitudes. If not blatantly, at the very least there is a remarkable struggle taking place within her, suggested by her use of language as well as her demeanour.

The Halo, after all, defines her as well.

If bearing it is the greatest honour, a mark of God’s favour, if it defines a person, then losing it has an equal power of definition. The distinction it confers on someone is inescapable, for good or ill, and either one dies gloriously as “God’s champion” or one survives it, survives its removal, and is deemed rejected and unworthy by this so magnanimous God. The Halo soaks up all of the positive value ascribed to it—meaning those who lack it adopt a negative one in contrast, be it Suzanne who had it and lost it or even Lilith, who should’ve had it and didn’t.

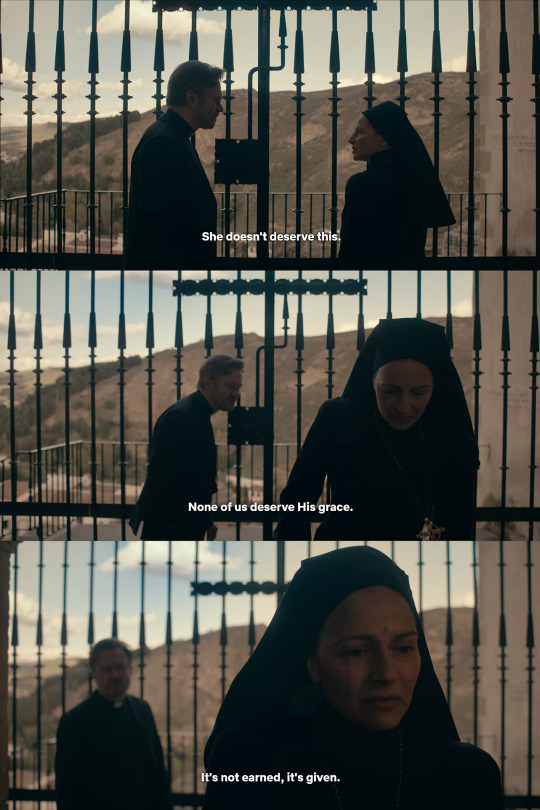

Still it is considered “a gift”, something given by God… One could say it is a form of grace.

Suzanne’s noun and Vincent’s verb have the same origin, of course, the same stem. Despite the argument between them in this other scene, ultimately there is agreement between the two of them judging by their choice of vocabulary and Mother Superion’s reaction immediately afterwards. If this were not true in some degree, there would have been little need for Mother Superion to correct Ava in the first place, for Ava calls the Halo “a hunk of magic metal”, yes, but she also refers to it as “top prize”, as a reward—which, unlike “gifts”, are meant to be earned, to use Vincent’s comparison. There is a mixture of concepts here.

Without wanting to overcomplicate this text, let us say that ideology is a certain way of understanding the world and that it constructs and is constructed by our discourse, our use of language. One of the functions of ideology is that of attempting to smother contradiction, to smoothen the world’s complexities, simplify them, rationalise them away, however incapable it truly is at accomplishing that given how reality is too complex to be so tamed. Here, then, we see a notable sort of contradiction in Mother Superion’s discourse (in her ideology) that isn’t easily solved: a detail, a problem left out from the thought system. She agrees that grace, in the form of the Halo or not, is given, yet she treats it as if it were earned. This is a crack in the wall; it’s an idiosyncrasy, proof of a subject torn between the different voices that compose her subjectivity, the fragments, the different discourses that, put together, make her up as a whole.

What could be more contradictory than calling something which has scarred her physically, mentally and emotionally a “gift”?

If we create and are created in turn by means of discourse (“you are God’s champion”), if we can only understand and interact with the world when it is mediated by discourses and their correlated ideologies, what would it have meant if Suzanne had assigned another value to the Halo?

The inversion of values would certainly have ejected her from the church. If the Halo, to her, gained negative value, thus allowing her to retain some amount of positive value, her participation in the institution would be impracticable. She would be at odds with the dominant ideology, its structures, its rules… And she would face the resistance Ava faced by assuming such antagonism.

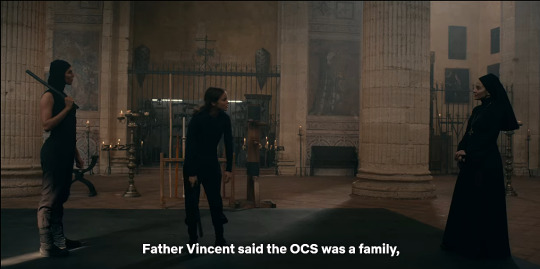

And sure, she might have regained some sort of “freedom”, but what would she have then lost? Resentment or not, there appears to be one central, recurrent positive value, one central desire to most characters in Warrior Nun and it would not be far-fetched to assume Suzanne shares in it herself and is unwilling to part with it.

B) The burden

Needless to say that if there is a generous deal of “burden” to Suzanne’s “gift”, there is also some “gift” in Shannon’s “burden”, judging by her mentioning the family she gained through bearing the Halo. Curiously enough, the dynamic of receiving something and paying for it with that very “gift”—Shannon getting a family and losing it by the very same means—is identical to the dynamics involved in getting Ava to accept her fate as warrior nun, by “paying” for the “gift” of life by risking that very same life in battle.

Shannon has received the “gift”—and fulfilled her role to perfection, allowed to thank God for it personally… If the Halo was taken from Suzanne, Shannon is the one “taken” because of it, alongside other ex-bearers.

Here there are no euphemisms. Shannon has lived the consequences of being “God’s champion” until the very end, so she has no need for distorted truths meant to keep things in order, to avoid questioning the principle of order itself which is the institutional view. There is still a struggle (there is always a struggle) as she admits to finding something positive (a family) through her loyalty to the cause even if the cause is what kills her and other women like her. The contrast between Mother Superion’s speech focused on individual responsibility and Shannon’s avowal of how it is “too great for one person to bear” tells us more than enough about how they each envision individuality, community, the possibility of action, who can make it come about—how life and death, different paths, different destinies, inform perception of the same thing.

Their values are inverted.

Mother Superion’s “gift” is Shannon’s “burden”; Mother Superion’s tendency, while alive, to value death (“You fight in His name”) is countered by a dead Shannon’s valorisation of life (“So much promise unfulfilled. So much life unlived. And for what?”) The scenes are in direct opposition to one another, they respond to one another as mirrored images.

So much so that the reply is not merely linguistic, hidden away in dialogue, but quite evidently displayed in visual terms as well. A mirror offers us reflections that are inverted—left in place of right, right as left—and so are these scenes inverted in relation to one another: in the moment of saying the sentences we’re concerned with, Mother Superion and Shannon stand in much the same place. If we do not notice, it is because the camera pans around in different angles—with the former, we watch the scene from a point at Ava's left, while the latter is shown from an angle at her right. We are literally treated to reflected images, seen from opposite points of view.

Colour, too, guides our reading of both scenes set side by side. With Mother Superion, we are in the realm of the church and its associated earthly tones as established throughout the first season, whereas Ava’s vision of Shannon paints the dream church in a shade of blue. Blue is, of course, the hue which had been mostly tied to Jillian Salvius, to ArqTech, to science. With science comes the concept of reason, as opposed to the sepia haze of faith.

Mary is also drawn against a backdrop of bright blue sky when she is investigating the docks and relying on her reason rather than her faith concerning Shannon’s death.

Shannon’s opinion on the Halo might be just as subjective as Mother Superion’s before her, but it is filtered through personal experience and observation, through reason rather than blind belief in a mission.

Yet we are forgetting something. Ava, having died already, claims there is nothing on the other side. If that is so, why is she meeting Shannon now? And why is this meeting taking place in circumstances that reflect previous events in an inverted manner?

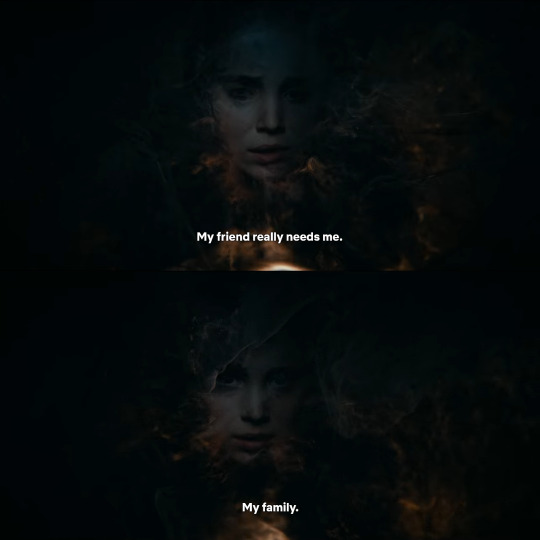

As dreams often reuse what we have lived when awake, re-rendering our memories, transforming them, so it is possible that Ava is not having a vision but a dream—that she is talking not to Shannon, but to some facet of herself, Ava, manifesting as Shannon after connecting with her memory through the warrior nun book.

As Ava clings to it and the knowledge it affords her, it would make sense for her conscience to finally figure out a proper retort to what she heard of Mother Superion in that earlier moment, a retort fuelled by new information and by her own reasoning. At the very least, it would be more plausible to consider this hypothesis than to assume her vision of Shannon is a real communication with her spirit granted by the Halo, for, if we are witnessing a new phase of manipulation, then the message being transmitted this time concerns the Halo’s “lifecycle” itself—and how it must be brought to an end. If it is sentient as some characters believe, why would it let Ava meet Shannon and be exposed to the idea of working against the Halo’s own interests of perpetuation?

After all, the implications behind Shannon’s words are evident: again, if the Halo also defines the woman, then it defines sister Shannon, sister Melanie and all other warrior nuns going back to Areala with one word which will soon apply to Ava and whomever follows: that word is dead, crushed under the burden.

And this time, the message, a sort of compassionate provocation (“a burden too great to bear”—even for you), hits its mark, inspiring Ava to end the tradition and be the last warrior nun.

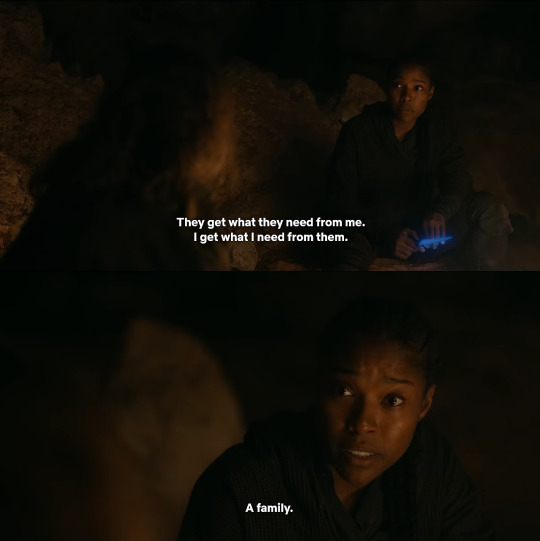

We are not in the semantic field of religion, even if it is there, in the background, being answered to; here we are not speaking of God or battles fought for this distant general in the sky, but of family, of women slaughtered in the name of a mission. This is no longer some ethereal question but an immediate concern. Whether this is Shannon or Ava herself subconsciously masquerading as Shannon to facilitate her own “awakening”, the point gets across now that it is transmitted in language that makes sense to Ava, now that there are common values between speaker and listener.

One could even hypothesise that, at this point, Shannon being a former warrior nun lends credibility to her words in Ava’s mind as she is a woman experienced in this role Ava is supposed to play.

If so, we can also understand the bridge of empathy that is built between Ava and Mother Superion later on when it is revealed that Suzanne, too, was a halo bearer and that she, too, has carried this “burden”. Both forge new understandings of one another through this common background and a personal exchange that is nothing like their first encounter—when the “gift” is said to have rejected the older nun, when its “burden” is divulged to Ava.

As Ava recognises Shannon, so do Ava and Mother Superion eventually recognise one another as well—so do they begin to comprehend how they did carry similar values, only obscured by their dissimilar ideologies and their resulting language use. If no other, then the value of family is what binds them together through Suzanne’s new disposition to embrace all of her sisters and Ava’s newfound conduct in considering them her sisters to begin with. They come closer in the catacombs and, at last, meet halfway by season two.

Yet we, the viewers, as touched by this miscommunication that ends well as we may be, after all of this talk of gifts and burdens, we remain none the wiser on what the Halo actually is.

C) The energy source

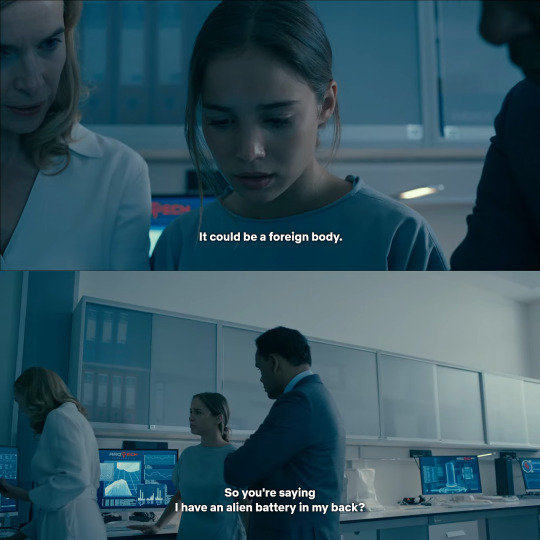

As previously exposed, we are kept in the dark because most sentences that speak of this iconic object in the series are subjective, focused on the characters’ own relationship to it or their ideas about it rather than any substantial data on what it might truly be apart from a “hunk of magic metal” currently in Ava’s back.

Perhaps because we spend so much time with the nuns, satisfied as they are with the logic of plain belief instead of concerned with tangible, provable things that can or should be explained. The most we get is the information on how the Halo is some kind of weapon, an amplifier attuned to the bearer’s body and soul.

Enter Jillian Salvius.

While her understanding of the Halo is admittedly insufficient, her research on it limited, her available vocabulary and scientific knowledge too slim (!) to encompass such an item, she does not say something like “the Halo is a mystery” or “a conundrum” as she says of Lilith later on. It would be true, just as it being a “gift” or “burden” is true considering those who called it thus, yet Jillian uses another sort of language instead.

Being a scientist, doctor Salvius opts for what we consider to be appropriate scientific modes of speaking, that is, by creating an impression of objectivity. It is not her personal reaction or opinion of the Halo that she offers, but whatever traits she can see or learn of in that moment: an energy source, an object that defies physics, a foreign body of undefined material. Ava “translates” this as being “an alien battery”, but the fact is that we are served a definition of the Halo unlike those we had before. It isn’t much, but for once we are not given a character’s personal interpretation of it…

Or so it seems. We none of us are capable of being fully objective, for none of us can rid ourselves of our selves—Jillian posits the Halo as an energy source, which seems innocent and impartial enough, but soon afterwards we understand what that means to her.

In themselves, the words “energy source” don’t carry many other connotations. Yet, for Jillian, these words that seem so neutral and “scientific”, so clear cut, do not sustain the facade of objectivity. She has spoken of energy before, it is an active component of her research, a common word in her lexicon; to Ava, “energy source” is “a battery”, but to Kristian and Jillian, who are part of ArqTech, who know what goes on within its walls, these words automatically acquire another meaning.

Yes, that of a battery, but one with a very specific purpose. Under the guise of neutral discourse, a very personal interpretation of the Halo, just as if it were a “gift” or “burden”, lies hidden. It is an energy source—one that doctor Salvius can potentially use to power her contraption. It is a “solution”, perhaps even a “gift”, of circumstance if not of god.

And it, too, defines Ava despite herself. When it fails, Jillian says she was wrong about Ava, not the Halo, thus conflating the two.

In the end, even she who might well be the smartest character, the one most closely connected with science and concrete knowledge, cannot guard herself from letting the unsaid (or “unsayable”) slip through her lips. She, too, in spite of her apparent objective language, exhibits a subjective kind of relationship with the world around her, influenced by the ideologies that cross her being.

D) Ending thoughts

Perhaps, when all is said and done, we are never truly able to follow that maxim we’ve seen more than once on Warrior Nun.

Perhaps we simply cannot think or act if we do not perceive things as at least partially related to ourselves.

It is not necessarily a bad thing, though, as long as different views can coexist, as long as they do not trample one another, as long as one person or group don’t elect themselves as the owners of truth, attempting to eliminate all who do not follow them as Adriel tried to do. In a democracy, in a place and a moment in history where there is freedom of thought and creed and speech, the phenomenon of various voices competing for the spotlight, taking turns under it is normal and healthy.

Warrior Nun gives us a fascinating insight on the multiplicity of voices that compose a society, even if there are elements of it which seek to suffocate those voices. It is a microcosm where different ideologies, through language, are confronted with one another, where they struggle to make sense of things—and where each of those points of view over a given subject might carry a morsel of truth. The Halo is a piece of metal and a gift and a burden and an energy source; none of these ideas or perceptions necessarily exclude the other, none is “more correct” than the other because, if so, then the question would be: as regards which character?

To Ava, at least, it is all these things and maybe more.

There are attempts to implant a hegemonic interpretation of facts. The very story of Areala, Adriel, the Halo’s trajectory along the centuries, how this is “the way it has been for one thousand years” is a strategy to cement a singular view. The repetition, the constant reworking of tradition, telling this story over and over with each warrior nun… That is the church at play, ideology trying to fill in any gaps, keep things as they are, conserve them and the structures that organise them, guaranteeing that things have one certain sort of sense and not another, one value, one meaning.

But life is not stagnant and people are not all swallowed whole by ideology even when they subscribe to it willingly, as a member of a church would. There are always things that cannot be explained, things that are beyond the scope of ideology—contradictions, pesky little details that escape the invisible goggles with which we look at reality. The truth is that it is far more complex than we can contain it with a few buzzwords, man-made or divine. There is always another side, always a reply, a constant dialogue between our different ways of seeing, understanding, being and, therefore, speaking.

A more visible example comes from those scenes in season two where Yasmine and Adriel are both telling the exact same story, only through their own perspectives, interpreting it in their own ways.

The show provides many opportunities to see how varied human voice can be, how the point of view of whoever is telling the story bears a mighty influence on the narrative, whether consciously or not, malicious or not. That, in turn, may inspire us to look around us, in the real world; to look at how we are representing things, others and even ourselves as well as how others represent us through the words we use.

This is not an exhaustive study, long as it is. As said before, it is but a glance at two scenes, two little lines of dialogue which are, however, intimately connected with others, with the stuff of the entire show—with the stuff of life. We could write more on how possessive pronouns and other sorts of phrases with the idea of the Halo “belonging” to someone or being “owned” by someone are used, just to remain in the area of discourse about the Halo alone.

But the present text has given all it had to give and its author does not wish to be a burden on her readers any more than she already has been.

#warrior nun#mother superion#ava silva#sister shannon#jillian salvius#look i tried my best not to throw jargon at you#it is strange for me to NOT mention bakhtin foucault pêcheux ducrot althusser greimas courtès perelman olbrechts tyteca & co#but the theory is there working beneath the text. i didn't want to scare anyone with the whole academic stuff#so i have tried all i could to use it without mentioning it directly and guarantee that anyone can understand what i've written#you will tell me if i have managed to convey my message or not#i hope i have. i don't like using a word like ideology without defining it but i want to trust in readers' intelligence#anyway. discourse analysis with some semiotics thrown in. i hope you have as much fun with this as i did!#i chose these two moments because i found them pretty cool#but we could talk about how language works in warrior nun for years probably#how it ties everyone together despite differences in understanding how it appears and reappears with new meanings#anyway I'VE SPOKEN ENOUGH#analysis and similar#exercises in observation

143 notes

·

View notes