#but sir that's my emotional support world weary general

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#but sir that's my emotional support world weary general#oh to be a snowflake that lands on russell’s lovely face#don’t talk to me i’m tending his wounds and smoothing his hair and whispering my love to him#it’s an us thing#wow i can’t handle him today#i woke up this morning and was attacked by longing for him#expect more as the day goes on#maximus my beloved husband my world weary sweetheart my shining light#the world turns on its axis for you my love#gladiator

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

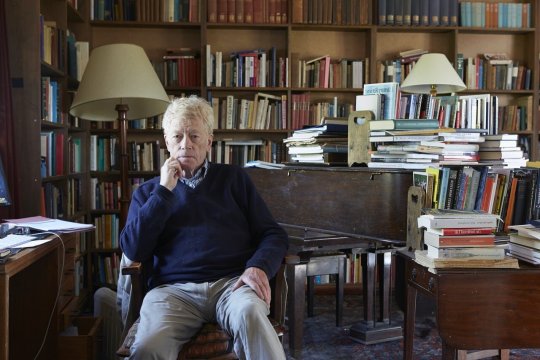

Anonymous said: I didn’t know too much about the late British philosopher Sir Roger Scruton until I followed your superbly cultured blog. As an ivy league educated American reading your posts, I feel he is a breath of fresh air as a sane and cultured conservative intellectual. We don’t really have his kind over here where things are heavily polarized between left and right, and sadly, we are often uncivil in our discourse. Sir Roger Scruton talks a lot about beauty especially in art (as indeed you do too), so for Scruton why does beauty as an aesthetic matter in art? Why should we care?

I thank you for your very kind words about my blog which I fear is not worthy of such fulsome praise.

However one who is worthy of praise (or at least gratitude and appreciation at least) is the late Sir Roger Scruton. I have had the pleasure to have met him on a few informal occasions.

Most memorably, I once got invited to High Table dinner at Peterhouse, Cambridge, by a friend who was a junior Don there. This was just after I had finished my studies at Cambridge and rather than pursue my PhD I opted instead to join the British army as a combat pilot officer. And so I found out that Scruton was dining too. We had very pleasant drinks in the SCR before and after dinner. He was exceptionally generous and kind in his consideration of others; we all basked in the gentle warmth of his wit and wisdom.

I remember talking to him about Xanthippe, Socrate’s wife, because I had read his wickedly funny fictional satire. In the book he credits the much maligned Xanthippe with being the brains behind all of Socrates’ famous philosophical ideas (as espoused by Plato).

On other occasions I had seen Roger Scruton give the odd lecture in London or at some cultural forum.

Other than that, I’ve always admire both the man and many of his ideas from afar. I do take issue with some of his intellectual ideas which seem to be taken a tad too far (he think pre-Raphaelites were kitsch) but it’s impossible to dislike the man in person.

Indeed the Marxist philosopher G.A. Cohen reportedly once refused to teach a seminar with Scruton, although they later became very good friends. This is the gap between the personal and the public persona. In public he was reviled as hate figure by some of the more intolerant of the leftists who were trying to shut him down from speaking. But in private his academic peers, writers, and philosophers, regardless of their political beliefs, hugely respected him and took his ideas seriously - because only in private will they ever admit that much of what Scruton talks about has come to pass.

In many ways he was like C.S. Lewis - a pariah to the Oxbridge establishment. At Oxford many dons poo-pooed his children stories, and especially his Christian ideas of faith, culture, and morality, and felt he should have laid off the lay theology and stuck to his academic speciality of English Literature. But an Oxford friend, now a don, tells me that many dons read his theological works in private because much of what he wrote has become hugely relevant today.

Scruton was a man of parts, some of which seemed irreconcilable: barrister, aesthetician, distinguished professor of aesthetics. Outside of brief pit stops at Cambridge, Oxford, and St Andrews, he was mostly based out of Birkbeck College, London University, which had a tradition of a working-class intake and to whom Scruton was something of a popular figure. He was also an editor of the ultra-Conservative Salisbury Review, organist, and an enthusiastic fox hunter. In addition he wrote over 50 books on philosophy, art, music, politics, literature, culture, sexuality, and religion, as well as finding time to write novels and two operas. He was widely recognised for his services to philosophy, teaching and public education, receiving a knighthood in 2016.

He was exactly the type of polymath England didn’t know what to do with because we British do discourage such continental affectations and we prefer people to know their lane and stick to it. Above all we’re suspicious of polymaths because no one likes a show off. Scruton could be accused of a few things but he never perceived as a show off. He was a gentle, reserved, and shy man of kindly manners.

He was never politically ‘Conservative’, or tried not to be. Indeed he encouraged many to think about defining “a philosophy of conservatism” and not “a philosophy for the Conservative Party.” In defining his own thoughts, he positioned conservatism to relation to its historical rivals, liberalism and socialism. He wrote that liberalism was the product of the enlightenment, which viewed society as a contract and the state as a system for guaranteeing individual rights. While he saw socialism as the product of the industrial revolution, and an ideology which views society as an economic system and the state as a means of distributing social wealth.

Like another great English thinkers, Michael Oakeshott, he felt that conservatives leaned more towards liberalism then socialism, but argued that for conservatives, freedom should also entail responsibility, which in turn depends on public spirit and virtue. Many classical liberals would agree.

In fact, he criticised Thatcherism for “its inadequate emphasis on the civic virtues, such as self-sacrifice, duty, solidarity and service of others.” Scruton agreed with classical liberals in believing that markets are not necessarily expressions of selfishness and greed, but heavily scolded his fellow Conservatives for allowing themselves to be caricatured as leaving social problems to the market. Classical liberals could be criticised for the same neglect.

Perhaps his conservative philosophy was best summed up when he wrote “Liberals seek freedom, socialists equality, and conservatives responsibility. And, without responsibility, neither freedom nor equality have any lasting value.”

Scruton’s politics were undoubtedly linked to his philosophy, which was broadly Hegelian. He took the view that all of the most important aspects of life – truth (the perception of the world as it is), beauty (the creation and appreciation of things valued for their own sake), and self-realisation (the establishment by a person of a coherent, autonomous identity) – can be achieved only as part of a cultural community within which meaning, standards and values are validated. But he had a wide and deep understanding of the history of western philosophy as a whole, and some of his best philosophical work consisted of explaining much more clearly than is often the case how different schools of western philosophy relate to one another.

People today still forget how he was a beacon for many East European intellectuals living under Communist rule in the 1980s. Scruton was deeply attached in belonging to a network of renowned Western scholars who were helping the political opposition in Eastern Europe. Their activity began in Czechoslovakia with the Jan Hus Foundation in 1980, supported by a broad spectrum of scholars from Jacques Derrida and Juergen Habermas to Roger Scruton and David Regan. Then came Poland, Hungary and later Romania. In Poland, Scruton co-founded the Jagiellonian Trust, a small but significant organisation. The other founders and active participants were Baroness Caroline Cox, Jessica Douglas-Home, Kathy Wilkes, Agnieszka Kołakowska, Dennis O’Keeffe, Timothy Garton Ash, and others.

Scruton had a particular sympathy for Prague and the Czech society, which bore fruit in the novel, Notes from Underground, which he wrote many years later. But his involvement in East European affairs was more than an emotional attachment. He believed that Eastern Europe - despite the communist terror and aggressive social engineering - managed to preserve a sense of historical continuity and strong ties to European and national traditions, more unconscious than openly articulated, which made it even more valuable. For this reason, decades later, he warned his East European friends against joining the European Union, arguing that whatever was left of those ties will be demolished by the political and ideological bulldozer of European bureaucracy.

Anyway, digressions aside, onto to the heart of your question.

Art matters.

Let’s start from there. Regardless of your personal tastes or aesthetics as you stand before a painting, slip inside a photograph, run your hand along the length of a sculpture, or move your body to the arrangements spiraling out of the concert speakers…something very primary - and primal - is happening. And much of it sub-conscious. There’s an element of trust.

Political philosopher, Hannah Arendt, defined artworks as “thought things,” ideas given material form to inspire reflection and rumination. Dialogue. Sometimes even discomfort. Art has the ability to move us, both positively and negatively. So we know that art matters. But the question posed by modern philosophers such as Roger Scruton has been: how do we want it to affect us?

Are we happy with the direction art is taking? Namely, says, Scruton, away from seeking “higher virtues” such as beauty and craftmanship, and instead, towards novelty for novelty’s sake, provoking emotional response under the guise of socio-political discourse.

Why does beauty in art matter?

Scruton asks us to wake up and start demanding something more from art other than disposable entertainment. “Through the pursuit of beauty,” suggests Scruton, “we shape the world as our own and come to understand our nature as spiritual beings. But art has turned its back on beauty and now we are surrounded by ugliness.” The great artists of the past, says Scruton, “were painfully aware that human life was full of care and suffering, but their remedy was beauty. The beautiful work of art brings consolation in sorrow and affirmation…It shows human life to be worthwhile.” But many modern artists, argues the philosopher, have become weary of this “sacred task” and replaced it with the “randomness” of art produced merely to gain notoriety and the result has been anywhere between kitsch to ugliness that ultimately leads to inward alienation and nihilistic despair.

The best way to understand Scruton’s idea of beauty in art and why it matters is to let him speak for himself. Click below on the video and watch a BBC documentary broadcast way back in 2009 that he did precisely on this subject, why beauty matters. It will not be a wasted hour but perhaps enrich and even enlighten your perspective on the importance of beauty in art.

vimeo

So I’ll do my best to summarise the point Scruton is making in this documentary above.

Here goes.....

In his 2009 documentary “Why Beauty Matters”, Scruton argues that beauty is a universal human need that elevates us and gives meaning to life. He sees beauty as a value, as important as truth or goodness, that can offer “consolation in sorrow and affirmation in joy”, therefore showing human life to be worthwhile.

According to Scruton, beauty is being lost in our modern world, particularly in the fields of art and architecture.

I was raised in many different cultures from India, Pakistan, to China, Japan, Southern Africa, and the Middle East as well schooling in rural Britain and Switzerland. So coming home to London on frequent visits was often a confusing experience because of the mismatch of modern art and new architecture. In life and in art I have chosen to see the beauty in things, locating myself in Paris, where I am surrounded by beauty, and understand the impact it can have on the everyday.

Scruton’s disdain for modern art begins with Marcel Duchamp’s urinal. Originally a satirical piece designed to mock the world of art and the snobberies that go with it, it has come to mean that anything can be art and anyone can be an artist. A “cult of ugliness” was created where originality is placed above beauty and the idea became more important than the artwork itself. He argues that art became a joke, endorsed by critics, doing away with a need for skill, taste or creativity.

Duchamp’s argument was that the value of any object lies solely in what each individual assigns it, and thus, anything can be declared “art,” and anyone an artist.

But is there something wrong with the idea that everything is art and everyone an artist? If we celebrate the democratic ideals of all citizens being equal and therefore their input having equal value, doesn’t Duchamp’s assertion make sense?

Who’s to say, after all, what constitutes beauty?

This resonated with me in particular and brought to mind when Scruton meets the artist Michael Craig-Martin and asks him about how Duchamp’s urinal first made him feel. Martin is best known for his work “An Oak Tree” which is a glass of water on a shelf, with text beside it explaining why it is an oak tree. Martin argues that Duchamp captures the imagination and that art is an art because we think of it as such.

When I first saw “An Oak Tree” I was confused and felt perhaps I didn’t have the intellect to understand it. When I would later question it with friends who worked in the art auction and gallery world, the response was always “You just don’t get it,” which became a common defence. To me, it was reminiscent of Hans Christian Andersen’s short tale “The Emperor’s New Clothes”, about two weavers who promise an emperor a new suit of clothes that they say is invisible to those who are unfit for their positions, stupid or incompetent. In reality, they make no clothes at all.

Scruton argues that the consumerist culture has been the catalyst for this change in modern art. We are always being sold something, through advertisements that feed our appetite for stuff, adverts try to be brash and outrageous to catch our attention. Art mimics advertising as artists attempt to create brands, the product that they sell is themselves. The more shocking and outrageous the artwork, the more attention it receives. Scruton is particularly disturbed by Piero Manzoni’s artwork “Artist’s Shit” which consists of 90 tin cans filled with the artist’s excrement.

Moreover the true aesthetic value, the beauty, has vanished in modern works that are selling for millions of dollars. In such works, by artists like Rothko, Franz Kline, Damien Hirst, and Tracey Emin, the beauty has been replaced by discourse. The lofty ideals of beauty are replaced by a social essay, however well intentioned.

A common argument for modern art is that it is reflecting modern life in all of its disorder and ugliness. Scruton suggests that great art has always shown the real in the light of the ideal and that in doing so it is transfigured.

A great painting does not necessarily have a beautiful subject matter, but it is made beautiful through the artist’s interpretation of it. Rembrandt shows this with his portraits of crinkly old women and men or the compassion and kindness of which Velazquez paints the dwarfs in the Spanish court. Modern art often takes the literal subject matter and misses the creative act. Scruton expresses this point using the comparison of Tracey Emin’s artwork ‘My Bed’ and a painting by Delacroix of the artist’s bed.

The subject matters are the same. The unmade beds in all of their sordid disdain. Delacroix brings beauty to a thing that lacks it through the considered artistry of his interpretation and by doing so, places a blessing on his own emotional chaos. Emin shares the ugliness that the bed shows by using the literal bed. According to Emin, it is art because she says that it is so.

Philosophers argued that through the pursuit of beauty, we shape the world as our home. Traditional architecture places beauty before utility, with ornate decorative details and proportions that satisfy our need for harmony. It reminds us that we have more than just practical needs but moral and spiritual needs too. Oscar Wilde said “All art is absolutely useless,” intended as praise by placing art above utility and on a level with love, friendship, and worship. These are not necessarily useful but are needed.

We have all experienced the feeling when we see something beautiful. To be transported by beauty, from the ordinary world to, as Scruton calls it, “the illuminated sphere of contemplation.” It is as if we feel the presence of a higher world. Since the beginning of western civilisation, poets and philosophers have seen the experience of beauty as a calling to the divine.

According to Scruton, Plato described beauty as a cosmic force flowing through us in the form of sexual desire. He separated the divine from sexuality through the distinction between love and lust. To lust is to take for oneself, whereas to love is to give. Platonic love removes lust and invites us to engage with it spiritually and not physically. As Plato says, “Beauty is a visitor from another world. We can do nothing with it save contemplate its pure radiance.”

Scruton makes the prescient point that art and beauty were traditionally aligned in religious works of art. Science impacted religion and created a spiritual vacuum. People began to look to nature for beauty, and there was a shift from religious works of art to paintings of landscapes and human life.

In today’s world of art and architecture, beauty is looked upon as a thing of the past with disdain. Scruton believes his vision of beauty gives meaning to the world and saves us from meaningless routines to take us to a place of higher contemplation. In this I think Scruton encourages us not to take revenge on reality by expressing its ugliness, but to return to where the real and the ideal may still exist in harmony “consoling our sorrows and amplifying our joys.”

Scruton believes when you train any of your senses you are privy to a heightened world. The artist sees beauty everywhere and they are able to draw that beauty out to show to others. One finds the most beauty in nature, and nature the best catalyst for creativity. The Tonalist painter George Inness advised artists to paint their emotional response to their subject, so that the viewer may hope to feel it too.

It must be said that Scruton’s views regarding art and beauty are not popular with the modern art crowd and their postmodern advocates. Having written several books on aesthetics, Scruton has developed a largely metaphysical aspect to understanding standards of art and beauty.

Throughout this documentary (and indeed his many books and articles), Scruton display a bias towards ‘high’ art, evidenced by a majority of his examples as well as his dismissal of much modern art. However on everyday beauty, there is much space for Scruton to challenge his own categories and extend his discussion to include examples from popular culture, such as in music, graphic design, and film. Omitting ‘low art’ in the discussion of beauty could lead one to conclude that beauty is not there.

It is here I would part ways with Scruton. I think there is beauty to be found in so called low art of car design, popular music or cinema for example - here I’m thinking of a Ferrari 250 GTO, jazz, or the films of Bergman, Bresson, or Kurosawa (among others) come to mind. Scruton gives short thrift to such 20th century art forms which should not be discounted when we talk of beauty. It’s hard to argue with Jean-Luc Godard for instance when he once said of French film pioneering director, Robert Bresson, “He is the French cinema, as Dostoevsky is the Russian novel and Mozart is German music.”

Overall though I believe Scruton does enough to leave us to ponder ourselves on the importance of beauty in the arts and our lives, including fine arts, music, and architecture. I think he succeeds in illuminating the poverty, dehumanisation and fraud of modernist and post-modernist cynicism, reductionism and nihilism. Scruton is rightly prescient in pointing the centrality of human aspiration and the longing for truth in both life and art.

In this he is correct in showing that goodness and beauty are universal and fundamentally important; and that the value of anything is not utilitarian and without meaning (e.g., Oscar Wilde’s claim that “All art is absolutely useless.”). Human beings are not purposeless material objects for mechanistic manipulation by others, and civil society itself depends upon a cultural consensus that beauty is real and every person should be respected with compassion as having dignity and nobility with very real spiritual needs to encounter and be transformed and uplifted by beauty.

Thanks for your question.

#ask#question#sir roger scruton#scruton#art#aesthetics#beauty#architecture#music#paintings#film#cinema#personal

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WORLD WAR ONE . THE WESTERN FRONT .

feat . @osterreiich and @rexblut .

Ludwig had practically begged for them all to let him go to the front.

He remembers first going to Gilbert. Neat, tidy uniform, adjustments made in the final moments before he enters the room with an air of confidence. The stern gaze he forced himself to maintain as he explained his reasons to go to the front, to follow in Gilbert’s footsteps, to prove to him that he could handle it like Gilbert had done for centuries before now. The firm no he’d received in return that stunned him. And nervous, Ludwig fixed his fringe, gently brushing it back with a gloved hand, stuttering over his first few words before finally starting to form coherent, persuasive arguments. Ludwig wanted to win over Gilbert’s favour first… Relying on Gilbert’s tendency for war and glory to tilt the argument.

It took him a bit longer than he expected, but eventually, he got an answer.

“Fine. You want to go to the front. And I’m proud of you for wanting to do that, and I guess I didn’t teach you all that strategy for nothing. But I’m stationed elsewhere on the front with my troops… So, you’ll have to ask Johan. And you know what? Roderich too.”

Roderich was next, he determined. Ludwig had mustered all his confidence to convince Roderich to let him out on the front, seeking the desperate approval of entering the war on his own volition. He’d even taken the chance to ask during a piano lesson with the other nation, taking the opportunity of a calmer environment to persuade him; keys playing a magnificent tune as they play, a duet unheard by all but the two, something the two could share compared to Gilbert’s strategizing and Johan’s survival skills. At first, it was an even stronger no than he’d received from Gilbert, but regardless of the initial answer, he did his best to convince his uncle to let him go. He was determined.

“I want to protect you, Roderich,” Ludwig would say; the nickname Roddy remains a decade unused, but he considers using it in his favour. Gentle coercion, he calls it. “Please, let me go to the front. You can’t stop me, realistically, but… I just want your approval.”

He still doesn’t know if he got a yes or no.

And last was Johan. Oh, Johan, even more insistent than Gilbert and Roderich combined that his no was the hardest to convince into a yes. He didn’t bother with formalities, only taking the chance to seek an answer during a friendly spar, a quiet moment between clashing steel against each other. They’d then spent the next few hours debating the point, with Ludwig wanting to fight and protect his people; Johan would argue that war is not glorious. Dear Ludwig would retort that it wasn’t glory he was seeking, merely protection for the people he’d sent to war. Was he guilt tripping? Well…

“I sent the blank cheque, Jo Jo. Please, this is my fault. I have to do something.”

“No! You have never been to war before, Ludwig. You-- have you seen my scars? Have you forgotten I’ve lived for thousands and thousands of years longer than you? I would not wish this upon anyone, least of all you.”

Their argument carries on through to dusk. The tense silence that follows is overbearing. But finally, an hour after the sun fully sets, Johan relents.

However, it isn’t without terms.

“You will be stationed with me. I will be in direct contact with Roderich and Gilbert the entire time we’re on the front. And if you die out there, or if you are severely injured, you will not be returning on any circumstances whatsoever. Understood?”

His enthusiastic nod is followed with a, “yes sir”.

…

Ludwig was not prepared for the horrors of the Great War.

Icy blue irises widen at the sight of bullets whistling past the top of their trench, colliding with whatever they could find beyond that, the ground flattened and muddy and bloody. Ludwig scrunches up his nose when he smells the terrible stench; an unbearable stench, of iron and rot and earth, of gunpowder and smoke, filling his lungs and threatening to make him cough in disgust. That same smell leaves a lingering taste on his tongue, followed by grains of dirt that he begrudgingly swallowed with his saliva. He feels so dirty. No matter how much the rain they got washed over him, it never scrubbed away the dirt on his uniform, the mud splatters on his face; and now that he looks at his uniform, it’s starting to fall apart, damage evident in the seams around his shoulders.

He glances upwards at the ever-growing height of their trench. So far, it’s dirt and mud held by wood, further protected by sandbags and set mud and-- Ludwig turns his gaze away.

Instead, Ludwig looks to the boy on his left. Younger, but not by much; old enough to convince someone that he’s 18, old enough to fight in the war. His green eyes are wide and his pale lips are chafed, mud and blood splattered and smudged across his face. The tale in those eyes says he’s seen thousands of lifetimes. Ludwig frowns. How could a human endure the pain and sorrow that comes with such a terrible war, how could anyone handle the pain and sorrow that comes with comrades dying around them? He could see it in the young boy’s face; he’s afraid to look up above that trench, to cross No Man’s Land. Ludwig asks him, “Geht’s dir gut?”, and he gets an unconvincing nod in return.

(A blatant lie, even now?)

Ludwig then turns to the other man on his right. An older man, in his 30s perhaps. Stare is steady and breathing is methodical, even; but Ludwig can see the fear in this man’s eyes, the determination dancing with the other emotion. He can’t help but ask if the man has a family waiting for him at home. “Ja… Berlin. Mein Frau und mein Sohn leben dort.” Ludwig only offers his prayer for him to return home to them in the end. The man gives a smile.

A deep breath. Silence. He remembers what Gilbert told him; silence means the enemy is up to something. It means they’re planning one of two things.

Silence is deadly.

The men wait in anticipation. He feels the tension rising as they all glance at one another, all wondering when the mortar fire will rain down on them once again, when the rifle shots will fly by the trench at the smallest hint of movement. Ludwig can hear his heartbeat in his ears with a steady rising heart-rate -- it’s terrifying. There hasn’t been a break in the war so far. There’s been constant sound and rapid fire and everything was wrong, so wrong, where was the mortar fire? Where are the shells?

Ludwig turns to the boy who’s entire body was shaking like a leaf, the fear so obvious, so evident; he reaches a hand to that boy’s shoulder with caution. He sees the boy flinch but calm.

And then he hears a whistling sound.

Ludwig shoots both his hands up to his ears but they ring with an agonisingly high-pitched sound, staggering to the ground as fast as he can. Blond strands of slicked back hair fall down to his face as his pike helmet finds its way onto the ground, with him throwing it off with such force; he can’t hear. He can’t fucking hear his pike helmet collide with the mud. He can’t hear the young boy on his left or the father of a young son on his right. Icy irises stare at the ground wide, trying to focus, trying to see straight, trying to gather himself enough to just kneel down and pick up his rifle, pick up that damned rifle, dammit Beilschmidt if you could just grab it and get back up-- !

He feels a pair of hands pick him up and shake him. Ludwig feels himself wince but focuses in on the person shaking him; Johan.

Weary hands reach up to brush his rogue strands out of his face, eyes darting around Johan’s face to find a focus, find out what he’s saying, trying to read his lips and gather what in the hell just happened. A hand reaches to Johan’s face.

Breathe. In… And out.

In…

“I’m fine,” he manages, hearing finally coming back. His voice cracks and it wavers with just the two words, and it betrays what he’s trying to say to his brother, but he strengthens his resolve and tries it again. His voice doesn’t waver so much this time when he manages to speak with a clear and concise voice, “I’m fine.”

A glance to his left. The boy is screaming… But he seems to have no evident injury. No wounds anywhere. Ludwig looks at him with surprise when it finally registers; he’s heard plenty about shell shock, the horrible circumstance some men find themselves in when they fight in this dreaded war, and a shell explodes right next to them, loud and ringing and un-apologetically dangerous. It forced normal men to their knees. It made those same men change so that they’d never be the same again. He just… Never thought he’d ever see it. He never thought he’d find someone suffering from it so much that some might consider the point of no return, this poor kid lost but not dead. The boy was so young.

How was this fair?

When he turns to his right, he sees the man; shaken, but still standing, pike helmet re-fixed onto his head as he turns his gaze to the blond next to him, looking him over. The man seems more concerned about those around him than himself. He sees the boy on the ground and immediately rushes to his aid, there to try and support him, to try and bring him back to reality; he remembers that this man is a father.

Ludwig wipes the dirt off his face to the best of his ability. He reaches for his helmet and brushes off the mud where he can, putting it back on his head with a slow uncertainty, eyes glancing over to Johan-- ah, General Lindemann. He’s nervous. Ludwig doesn’t want to admit it, but there’s a sinking feeling in his stomach as the mortar fire continues.

Icy irises gaze absentmindedly in the distance, listening out for the shells, waiting for the silence to consume the battlefield once again. Cacophonous screams carry through the air from both sides of him, mud and dirt splattering down from the collision of shell against ground, threatening to blind anyone that dares look up while the symphony of fire and destruction. All the disturbance of earth raises the terrible smell from earlier; the dust and iron and rot and smoke fill his lungs enough to make him cough. He hates this more than he can care to imagine... The boy and man stick beside each other, the father using his paternal instincts to keep him calm enough to handle this constant horror.

Ludwig had never seen the horrors of war until now.

And now that he’s on the Western Front, facing the worst of wars, the war to end all wars, only a few words manage to leave his mouth in the silence that comes.

“Möge Gott uns beistehen.”

#* strength is what i gain from the madness i survived ! / muse : germany .#osterreiich#rexblut#/ i finally finished writing this ! wow look at this pain !#/ in which l.udwig finally experiences the horrors of war and wants to go home :')#/ he's Baby like . barely 18 in physical age .#/ and 43 in actual age .

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Long Way Home (6/10)

The reception for this story continues to be so generous, and I can't thank you guys enough. I spent so many months anxious about whether anyone would like this fic, whether there would still be an audience for it, whether it would be worth the hundreds thousands of hours I've spent laboring over it/thinking about it/tweaking and re-tweaking it - but you all have been incredibly sweet and supportive, and I'm so grateful to you all for cheering me on. Hope you enjoy this week's installment!

As always, thanks to my beta, @captainstudmuffin, and to @lifeinahole27, @clockadile, and @ladyciaramiggles for their additional feedback. Additional thanks to my wonderful CSBB artists, @waiting-for-autumn and @giraffes-ride-swordfishes for providing some gorgeous artwork to accompany this fic! Links to their illustrations of certain scenes (*) will be in the text - go show them some love!

Find it on AO3. Nautical term glossary here.

Missed a chapter? Get caught up here.

Summary: After an unnaturally long life fraught with personal tragedy, Killian Jones has become known throughout the realms as the infamous Captain Hook, an opportunistic ne’er-do-well and one of the most formidable pirates to ride the waves. When he crosses paths with a mysterious young woman with no memory of who she is or how she arrived there, he recognizes the chance to claim a monetary reward that will constitute his biggest score yet. But a journey across the world to get her home leads to a series of adventures that reveal that her value lies in far more than gold and jewels. A Captain Swan Anastasia AU - sort of. (Captain Swan Enchanted Forest AU. Romance, Adventure, & Eventual Smut. Rated E.)

Warning: Brief but graphic depictions of violence, peripheral character death, and smut.

Alec is back on his feet in several days, though he continues to be hobbled by his injury and he’s restricted to light duties like mending sails and cleaning weapons. Swan begins to keep him company under the guise of having him teach her these skills, and when every sail is repaired and every gun, canon, sword, and dagger aboard polished to a shine, she goads him into spending another morning teaching her how to tie different kinds of sailor’s knots.

The youngest member of the crew takes her attention in stride. “If you spend any more time with me, ma’am,” he jokes on their fourth morning together, “Cap’n’s bound to get jealous.”

Swan hums, the side of her mouth quirking. “The Captain is a grown man who can afford not to be the center of a woman’s attention all the time,” she replies airily, picking her latest knot out of her piece of practice rope. “Heaven knows he’s probably had enough women fawning over him to last a lifetime.”

Alec chortles and agrees with a bob of his shiny, bald head. “Even so – and not that it’s any o’ my business, milady,” he says quietly, darting a glance up at the ship’s wheel where Hook is talking with the helmsman, “when I see a man look at a lady the way Cap’n does you, it’s generally safer t’ keep my distance.”

“Hmph.” Swan wills her cheeks not to warm and tries to ignore the way her heartbeat quickens at the implication. “If the Captain looks at me differently, it’s because he thinks our friendship is a good investment,” she points out. The knot finally comes undone, and she twirls the rope triumphantly in her hands. “And if he has expectations with regard to how I spend my time, he hasn’t told me.”

“Pretty sure he knows better than that, ma’am.”

She huffs and flashes Alec a grin, her eyes laughing. “Well, at least all his time around women has taught him a thing or two.” She stands and offers him a hand. “It’s almost lunchtime. Do you have other duties, or can I walk you to the mess?”

He waves her off and grabs the wooden staff he’s been using for support. “I think I can do it.” He plants the staff on deck and pauses for a deep breath before he hoists himself up with a strained grunt. Swan gasps when he suddenly hisses and teeters, an agonized sound escaping him as he crashes to the boards.

“Alec?” she yelps. She whirls toward the stern deck. “Hook? Help!”

The Captain’s head whips around at her call, and he all but flies down the ladder, reaching them as quickly as any of the other men. He gently nudges her to the side and kneels next to his fallen crewman. “What is it, lad? The leg?”

Alec groans and nods, rolling over on to his back with pain creasing his forehead. “It’s been worse since last night,” he confesses.

Hook works quickly to untie the wide bandages encircling his thigh and carefully peels back the edges of the split in the Alec’s trouser leg, which is stiff with dried blood from the original injury. His lips form a thin line as he peers at the exposed skin. The flesh near the edges of the laceration is tinged a beefy red and so swollen it resembles the skin of an orange. “This doesn’t look well,” he mutters. He glances up at the other men standing by. “Get him below and cut the trouser leg off,” he orders, gesturing at the soiled fabric. “Find him a clean bandage, and no further duties until he’s healed.” He stands up and allows Martin and Smee through so they can bear Alec up on his good leg and help him away.

Swan appears at his side, anxious. “Will he be alright?” she asks softly.

Hook sighs, suddenly looking very world-weary. “I don’t know,” he admits once Alec is out of earshot. “I���ve seen the same happen to many a sailor. We’ll watch it closely. If it gets much worse, he may have to choose between losing the leg or losing his life.”

The color leaves her face, and he turns and wordlessly takes her hand, settling it in the crook of his left elbow as he escorts her toward the hatch leading to his quarters. He’s silent for a few paces. “You’re worried about him.”

“Of course I am,” she replies with a puzzled frown. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

“No, it’s just…” He scratches the back of his head with his brace, his eyes on his toes. “I’m still surprised that you’ve come to care about a band of pirates, I suppose.” His brows lift. “Unless there’s something special about Alec?”

For some reason, the question sets Swan brimming with impatience, and she rolls her eyes, in no mood for his teasing. “Really?” she demands. When his only answer is an enigmatic shrug, she huffs. “Alec’s tall and he can swing a sword, but he’s still barely more than a boy, Hook.” She pulls a face. “An actual boy, not a one hundred fifty year-old in a boy’s body; I know you brought him on after Neverland.” She sighs, forehead lined with concern. “He’s a kid, and he’s hurt and scared and… and I just thought he could use a little company these last few days.”

Hook nods slowly, his expression turning touched and a little sad as he brings his hand up to cover hers. “You’re right,” he murmurs apologetically. “You’ve shown him a great kindness. We aren’t used to such things, but he needs all of it he can get now. There’s a good chance this week does not end well for him, one way or another.”

Swan swallows the enormous lump that rises in her throat. “Maybe he’d let me read to him,” she offers in a small voice. It feels like so little – like nothing – but it’s all she can think of.

Hook flashes her a muted smile. “I’m sure he’d appreciate that, love. ��Few sailors are lucky enough to have a good-hearted woman to help look after them in times like this. Your presence is a gift to this crew.” His fingers tighten affectionately over hers, and his eyes fall back to the deck, his tone growing somewhat despondent. “I think you’ll be sorely missed.”

She blinks rapidly at his sentiment, her mouth forming a watery little smile, and as they descend below deck to have lunch, her heart feels heavy, weighed down by the cloud of Alec’s predicament and churning with mixed feelings. She chuffs silently. Leave it to Killian Jones to surprise her again. He may have tried to tease her about her relationship with Alec, but contrary to his crewman’s suggestion, he doesn’t seem jealous – not really. She should be glad for that, impressed by that. Instead she feels more than a tiny prick of disappointment. And more than a little vexed at how she feels.

Lunch is quiet, the mood solemn, and though she catches Hook’s eyes on her from time to time, the pair of them remain largely lost in their own thoughts. Swan finishes quickly and hops up to select a book for Alec. “What do you think he’d like?” she muses, walking her fingers across the titles.

“Captain?”

Their heads turn toward the muffled call and the sound of rapidly encroaching footsteps in the passageway outside. A hand knocks fervently on the door.

Hook finishes his last bite and brushes a stray crumb from the corner of his mouth. “What is it, Smee?” he answers.

The knob turns, and Smee pops in. “A ship, sir,” he reports. “Packet, by the looks of it.”

Hook frowns. “Slavers?”

“Probably.”

“Slavers?” Swan’s voice draws their attention.

Hook turns toward her, his countenance darkened. “Aye. This close to the Foundering Islands, a ship like that is almost certainly carrying fresh prisoners of war to the slave markets east of here.” He glances back at his first mate. “Maintain course and speed, Smee. I’ll come up shortly.”

Smee gives a hasty nod and scuttles away.

The door closes behind him, and a sigh passes Hook’s lips. He rises and reaches for his sword belt.

Swan watches him put it on. “Are you going to engage them?”

To her confusion, he shakes his head as he does up the buckle. “Not likely. Every choice to engage is a calculated risk, love. We’re a man down now, and there isn’t much to be gained from attacking a ship like this. Slavers can be a nasty lot, and we’re not in the business of capturing or selling slaves.” He reaches for his coat with a scowl. “It’s a disgusting practice.”

Her brow creases in thought. “What if… what if you took the ship but set the slaves free?” She meets his confounded look with an earnest stare. "You could help them."

Hook blinks, conflicting emotions writing themselves all over his face. “Swan…”

“No, think about it. You became a pirate to escape service to a ruthless king,” she argues, her voice growing bolder. “Why should all those people stay condemned to life under a master if the Jolly can save them?”

He flexes his jaw with indignation. “I’m not in the business of risking my crew in order to play hero.”

“What if the crew thought it was worth the risk?”

Hook's countenance hardens, and he looks away, his gaze dropping to the floor as he turns to leave. He strides away without another word, and she watches the door shut behind him with sad eyes, frustration dragging her stomach down to the depths and leaving her unsure whether to appreciate or regret this acute reminder that, regardless of whatever misguided feelings she may harbor for the Captain, she may have put her faith in his good heart too soon.

* * *

His boots fall heavy on the deck as Hook stalks across the boards to join Smee at the wheel, his chest still aching from the disappointment on Emma’s face.

“Steady at your ten o’clock, sir,” Smee informs him briskly, nodding toward the northwest horizon.

Hook squints at the telltale rig configuration of the smaller vessel, his lips pressed into a grim line as he pulls out his spyglass and examines the ship more closely.

“I assume we’re leaving them alone?”

He licks his lips and stows his glass, his eyes landing upon the angry scratches that zigzag across the worn surface of the black sideboard next to the ship’s wheel.

It’s not too late to start over. I can change, Bae. For you.

You say that. I know you’ll never change, because all you care about is yourself.

The last conversation he had with Baelfire in Neverland years ago leaps into his mind – the last time he hoped for a happy ending for himself and someone he cared for. The last time that someone had looked on him with hope fading from their eyes.

Hook stares intently at what remains of the ‘P’ and ‘S’ he once carved to orient the lad to the sides of the ship – letters obliterated in a fit of rage – and he swallows thickly. Regret slams down on him like a tidal wave as he remembers how he chose self-preservation over courage and anger over contrition, betraying Bae to the Lost Boys the moment he and the lad had had a falling out. Coward. His hand curls into a fist.

He won’t lose his chance with Emma. Not like this.

“Call all hands on deck,” he says quietly.

Smee turns. “Sir?”

Hook fixes the other ship with a determined glare. “All hands,” he repeats flatly. “I need to address the crew.”

Though clearly perplexed by the demand, Smee knows better than to ask questions. He closes his open mouth and hurries away, and five minutes later the men are assembled around the main-mast, murmuring amongst themselves at this unexpected summoning.

Hook stands above them on the stern deck, his hand resting on the rail near the ship’s bell.

“I’ve called you here,” he calls, “with an opportunity.” His voice rings out across the Jolly, and every set of eyes is upon him. “To port lies what is most likely a ship belonging to slavers, men who put a price on flesh and trade other people as if they were chattel. It’s been our custom to let slavers alone because I refuse to make a profit off of cargo that shouldn’t be cargo and because we don’t raise swords for anything other than profit or revenge.”

Sounds of agreement ripple through the crew.

“But I am proposing a change,” he continues. “I claimed this ship and turned pirate to free myself from the service of a king who used loyal men like me as puppets. He betrayed my trust, and my brother died because of his treachery. We,” he says, gritting his teeth, his eyes flitting over the faces of those assembled, “are men of honor. We live by a code. We go where we please and take what we like and answer to no one but each other.” Cheers ring out, and he yanks his cutlass from the scabbard and swings it toward the other ship, his voice rising. “And I say it is a foul thing for us to claim to value freedom but turn a blind eye to cruel men who make a living depriving others of it!” he bellows. His heart rams against his ribs. “I know there is risk and little profit to be had,” he admits, “but we are the most able crew to sail the seas, and for the sake of our decency and our self-respect as pirates, I say we take those bloody slavers down! Will you stand with me?”

Roars of approval fill his ears, fists jutting into the air in solidarity, and the voices of his men form an enthusiastic chorus as they chant, “Captain Hook! Captain Hook!”

Hook hears movement and a gratified hum behind him and turns to see Emma standing nearby, her ponytail flapping over one shoulder like a victory banner on the breeze. She leans against the sideboard, her face bright, her cheeks rosy, and her small smile brighter than the sun. Hope fills him anew when she gives him a little nod, and he nods back. Perhaps there’s something more valuable than gold or jewels or even revenge worth fighting for now, he thinks.

He allows her to remain on deck as they shift course to intercept the other ship, and Swan watches with sober fascination as they hoist the colors and fire the customary warning shot. As expected, the slavers refuse to surrender.

“Leave them alive, if you can,” Hook barks on the Jolly’s approach. “I want to send a message.”

He turns back to Emma. “I know how you feel about being asked to stay below, love,” he acknowledges gently, “but perhaps you’ll oblige me this time?”

He considers it a small miracle when she concedes without protest. Emma turns toward the hatch to his quarters, pausing to lay her hand on his shoulder and gaze up at him with anxious eyes. “Be careful?”

He gives her a soft smirk and risks reaching forward to cup her face, his thumb drifting softly across her skin. “You try not to worry, and I'll try not to need a daring rescue today. Alright?” His heart leaps at the way she blushes, a chuckle playing on her lips as she heads down below.

The crew of the slave ship numbers about fifteen, and though they put up a fight, this particular group proves no match for the men of the Jolly Roger, even with the latter utilizing non-deadly force. Within twenty minutes, the slavers find themselves trounced, bound, and forced to huddle in the center of the main deck, their expressions a mixture of anger, resentment, and fear as they eye the pirates that form a tight circle around them.

“Which one of you is in charge?” Hook demands, striding forward. Glances dart toward a heavy-set scoundrel with a barrel chest and a bald head whose skin is bronzed and leathery from the sun. Hook tips his chin at him. “You.”

The man raises his dark, beady eyes.

“You know who I am?” He sees the slaver glance at his hook, and he smiles coldly. “You do. Excellent. So you know how lucky you and your men are to still be alive.” His face hints at a snarl. “You are being given quarter this once in order to deliver a message to your fellows in the slave trade.” Hook lifts his head and raises his voice. “Personal freedom is not a commodity to be bought and sold, and as pirates, we can be indifferent no more,” he announces. “You are no longer safe from our interference. We will demand surrender from any slave ship we come across, and we will encourage our brethren to do the same.” He draws his sword on them, his voice taking on a deadly timbre. “You are relieved of this ship and everything and everyone aboard. Get to your boats and go before I decide to stop being generous.”

Most of the slavers climb to their feet and shuffle off under the escort of his men, but their leader lags behind and glowers at Hook. “So you steal property and yet suppose yourself the better man,” he sneers.

Hook launches forward, his blade slicing through the air and biting the flesh just below the other man’s jaw. “People,” he hisses, rotating the sword edge with excruciating slowness until it just barely draws blood, “are not property. And I’m a better man now than when I allowed you to continue this bloody business unfettered.” He hooks a large loop of keys off the man’s belt and plants a boot in his stomach, watching with grave satisfaction as the slaver wheels across the deck and crashes into the gunwhale with a tortured grunt. The man crumbles to his knees, and Hook snorts. “Get him out of my sight.”

He finds his way below, and his stomach churns increasingly as he draws closer to the hold, the air growing uncomfortably warm and thick with the stench of unwashed bodies and human foulness. He finds Martin and Roberts waiting for him at the hatch with revulsion in their eyes.

“Are there many?” he asks quietly.

Martin nods, his expression grim. “Aye, Captain. See for yourself.” He steps aside, and the open hatch comes into view.

The heat and smells are immediately magnified, hitting him in the face like a sordid cloud as Hook kneels and peers down into the dimly lit space, and it takes everything he has not to retch. He looks away for a second, face clenched in a grimace, before steeling himself and turning back to examine the hold. The terrified eyes of men, women, and even some older children stare back up at him. The light of a few hanging lanterns casts shadows across their faces, and he can see that they’re packed shoulder-to-shoulder like livestock, the close and distant clinking of their chains confirming for him that the entire hold is full with bodies.

His gaze locks onto a boy, aged perhaps eleven or twelve, with shaggy dark hair. The lad’s pale, round face is smudged with tears and filth and set with wide, timid eyes, and something in Hook’s chest wrenches as his own time as slave to a series of hardened captains – six years of childhood that was several lifetimes ago – suddenly feels as though it’s not so far away. Fury flares in his blood. “Get them out,” he growls, managing to hide the quaver in his voice as he tosses Martin the ring of keys, “and see if any of them knows how to sail this vessel home.”

He hurries back above deck, pausing under the guise of visually inspecting the sails in order to catch a few deep lungfuls of the ocean air and allow his pulse to stop hammering. His ears pick up the steady squeaking of pulleys as his men lower the boats full of slavers astern, and there’s a pair of splashes when they finally hit the water. Good riddance.

Hook hustles to the aft rail to watch the slavers depart. Pistols emerge, and a handful of his men train their weapons on the boats to keep the other crew in line as they go. His eyes dart over to the Jolly and to the hatch leading to his quarters, and the thought of Emma holed up safely below while the slavers row in the opposite direction brings a relieved sigh to his lips as he looks to Thomas and Smee standing guard on the Jolly’s deck and gives them a grateful nod.

The sound of dozens of footfalls causes him to turn around, and satisfaction curves his mouth at the sight of the first of the former slaves climbing up and out into the sunlight. Many cringe and duck behind their hands as they adjust to the brightness, but there is excited chatter amongst them, and though he can see plenty of arms and legs adorned with red marks, the irons that caused them have been abandoned below.

All told, over fifty people emerge from the hold, followed by Roberts and Martin, who appear as happy as any of them to be out of the bowels of the ship.

Hook approaches. “That’s everyone?”

Martin swipes his sleeve over his damp brow, looking weary. “Yessir.”

“Can they sail?”

He bobs his head. “Aye. I counted a dozen of them who identified as seafarers. They think they can manage.”

“Provisions?” Hook turns to Roberts.

The quartermaster hums the affirmative. “Stores’re fine. They’ll do alright, I think. They estimate their homeland’s less than a week from here.” He scratches at the base of his neck. “Shall we investigate the crew quarters, Captain?”

Hook smirks half-heartedly. “Of course, Old Man. What kind of pirate do you take me for?”

It’s not a huge haul, and much of what they find by way of clothing and linens they leave for the former slaves, but they do locate a fairly generous purse in the main cabin and some useful supplies worth scavenging – weapons and ammunition, extra lantern oil and wicks intended for the slavers’ return trip from market, parchment and writing supplies, pipe tobacco, and a few bottles of quality spirits. The Captain hums with approval as he finishes counting the money with Roberts and seals the coins back into the satchel.

“Not a bad day’s work, eh, sir?” Roberts asks, accepting the purse for safe-keeping until it can be divided amongst the crew.

“No.” Hook leads him back up the ladder, savoring the swirl of wind that greets him when they emerge on deck. He takes in the scene before them. Some of the former slaves inspect the rigging while explaining the structure of the ship to the less experienced sailors, others haul buckets of water from the sea in order to wash, and children weave in and out of the crowd like a school of fish as they chase each other across the deck. Their youthful laughter fills the air, and Hook cranes his head to watch the lad he saw before scramble by with his mates, all traces of fear gone from his small face. Where once the deck of this ship was dour, it’s now filled with life, with hope, and this, this is their doing. Correction, he thinks. This is Emma’s doing through them. This is the work of an angel. “No,” he says, his chest swelling with a peace he hasn’t known in a long time. “Not a bad day’s work at all.”

* * *

The taking of the slave ship is a much quieter affair than their run-in with the pirate hunters had been, and Swan has the benefit of company to distract her now as she waits below deck. She knocks on the open door of the crew quarters and pokes her head in. “Alec?”

Faced away from her in his berth, the young man cranes his neck, arching a bit off his pillow to meet her eye. “Milady?”

She steps across the threshold, cradling a book in her arms. “Mind if I wait here with you?” she asks, coming in to stand in front of a bench across from him. “I could use a distraction.”

He smiles appreciatively and nods, gesturing for her to have a seat. “Me too.”

She settles down, pulling her legs up under her in order to sit cross-legged. “How do you feel?” she asks, studying him. As Hook had ordered, the fabric of his trousers has been completely cut away to expose his leg, and a clean bandage is wrapped around his wound.

Alec makes a noncommittal noise. “The pain’s not bad when I don’t stand.” He looks up at her, his face guilty. “I’m sorry if I frightened you earlier, ma’am.”

She shakes her head. “It’s alright. I’m sorry I didn’t notice you weren’t feeling well today.”

“Nah. S’nothing,” he says, attempting to sound cavalier. He glances at her book. “What’s that?”

Swan holds it up for him. “Legends of the Deep. I’ve been working my way through the Captain’s collection. Do you know it?”

Now it’s Alec who shakes his head. “Never been very good at readin’, t’ be honest.”

“Perhaps I could read it aloud?”

He brightens. “I’d be much obliged, ma’am.”

Swan grins and pulls the book open to the first page. She clears her throat and wets her lips. “It is said that the sea is an enchanting place, full of beauty and mysteries beyond the comprehension of mortal men…”

She’s a dozen pages in when the sound of Alec’s snoring causes her to look up. A muted smile plays on her mouth, and she sighs, softly swinging the cover shut. Her eyes fall to his leg, and worry wrinkles her forehead once more as she rises and slips out of the cabin, pulling the door softly closed behind her.

Standing in the corridor, she glances briefly in the direction of the Captain’s quarters, gnawing at her lip before she decides to climb the ladder to the hatch instead, her heart pounding as she eases it open just a few inches so she can peek outside.

Her ears strain for clues as to what’s going on, and she grows excited several moments later when a familiar pair of boots passes a few feet from her nose. “Thomas! Thomas!” she hisses.

The boots turn to face her, and Thomas kneels, his amused expression coming into view as he cants his head sideways to meet her eye. “Milady?”

Heat creeps up from her neck, and she suddenly feels a little silly. “Is everything going alright?”

He chuckles. “Very well, ma’am. The slavers are being loaded into boats as we speak. We’ll see that they leave without any trouble,” he assures her, patting the gun tucked into his belt. “Cap’n’s gone below to see to the slaves, I think.”

Swan exhales, a relieved smile coming over her face. “That’s good.”

“Aye.” He nods with a grin. “Sit tight, ma’am. It might take ‘em a bit to get sorted, but I imagine we’ll have everyone back aboard soon enough.”

She beams and retreats, feeling much more content as she descends the ladder. They’re safe. He did it. Pride in the Captain brings a private smile to her lips, and her heart flutters. She gives a relieved huff. Perhaps she wasn’t so far off in her read of him as she feared.

She elects to continue reading in his quarters where the light is better, hunching over his table with the book open in front of her. Within minutes, however, her own eyelids grow heavy and her head begins to loll with the weight of sleep.

* * *

“Swan?” Hook eyes her still form and murmurs her name, wearing a soft expression as he moves around his table to stand beside her. He pauses a moment to study the serenity on her face and the gentle rise and fall of her shoulders with each breath. Her long lashes are dusky against her cheeks, her exquisite features blissfully free of emotion, and she rests on the table, her head cradled on one folded arm while the fingers of her other hand grace the cover of an open, overturned book. A wavy lock of her hair lies haphazardly draped over her eyes, and she’s so achingly beautiful that his chest hurts.

He has no clue what he’s done to deserve time with this woman, but he was guilty of understatement when he called her a gift to his crew. Her presence has infused the Jolly with a new sense of life and excitement and given the men a fresh collective purpose in keeping her safe and delivering her home. He’s watched them over the past several weeks – noticed them smiling more freely and singing more heartily. He’s seen them beam proudly every time they make the Princess laugh. He might be completely besotted, but it’s clear they’re all a little in love with her, and the prospect of leaving her behind in Misthaven makes him so melancholy that he’s wished more than once for an excuse to prolong their journey with an unplanned stop in port or a detour to a less direct course. He feels a pang of guilt about it now that Alec’s condition actually makes a stop in a port to find a surgeon a real necessity.

A small voice inside tells him not to wake her, but it’s as though his hand has a mind of its own when he reaches forward and delicately brushes her hair out of her face. The graze of his fingertips over her forehead causes Emma to stir. She sucks in a deep breath and wrinkles her brow, and he pulls his hand away just before she opens her eyes and looks up at him.

Her face lights up, and she sits up hastily, looking a bit embarrassed to have fallen asleep. “You’re back.”

He relaxes and nods. “Aye. Some of the men are still on the other ship conferring with the people about how they plan to sail her home, but I wanted to come check on you.”

Emma eyes him proudly. “You did it then. You set them free.”

His cheeks warm. “Yes, well, someone convinced me it was the right thing to do,” he reminds her, glancing at the toes of his boots with an uncharacteristically humble grin.

“And here they say Captain Hook doesn’t care about anyone but himself,” she teases.

He looks back up at her, considering her statement with a pained smile. “Maybe I just needed reminding that I could,” he says at last.

The admission hangs between them for a moment, and his heart somehow feels both heavier and lighter for having made it. Emma’s expression sobers as she studies the emotions flitting across his face with that soul-searching stare of hers, and, though he can’t identify all of the feelings jumbled up inside him, he realizes that, for the first time, he’s not as afraid of what she might see.

Thanks for reading! Ready for the next chapter? Click here!

#csbb#cs ff#cs fic#captain swan#captain wench#captain duckling#cs ef au#cs anastasia au#cs au#cs au ff#ouat ff#ouat fanfic#my writing#the long way home

88 notes

·

View notes