#but its late and i do NOT want to be rooting through the hoover to find it right now

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nothing quite like deciding to finish off a jigsaw to get some satisfaction when everything just feels off and then discovering there is a piece missing

#and i hoovered the entire lounge and took the rug up and everything#but its late and i do NOT want to be rooting through the hoover to find it right now#anyway i hope the higher power having a laugh at my expense is enjoying themself

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekend Top Ten #359

Top Ten Future Transformers Spin-Offs

So I finally went to see Bumblebee, the delightful, charming, and utterly loveable Transformers spin-off/prequel from Travis Knight. It’s a great little film, on a much smaller scale than the other films in the series, offering some beautifully retro Amblin vibes whilst telling a more compelling and characterful story full of warmth, heart, and genuinely good performances. And as a great big Transformers fan (is there no Transformers equivalent of Trekkie or Browncoat I can adopt?) I got a huge thrill from the recreation of war-torn Cybertron, straight from the iconography of the classic ‘80s cartoon series. I spent the first ten minutes just cooing and bubbling, going “Look! Wheeljack! And Arcee! And Ratchet! And Soundwave! And Shockwave! And Ravage!” and so on.

Anyway, I think the film is all kinds of great, and captures the spirit of the brand and the stories much better (in my opinion) than the Michael Bay ones do. But if one spin-off could succeed where the “mainline” films failed, could that trick be repeated? And this got me thinking: what other stories and characters are ripe for the big-screen treatment? Where else can Transformers go cinematically, without doing any kind of real follow-up to The Last Knight?

Here, then, are ten suggestions. Rather than proposing any kind of reboot or reimagining of the property, I've tried to find stories that could exist within the loose canon of the movies (which, to be fair, is a fairly shifting proposition anyway, with several movies contradicting one another in large and small ways). So, inspired by my love of the original characters, and often by stories I’ve read in the meantime, and with the potentially large caveat that I’ve still not seen The Last Knight and therefore might actually be retreading story grooves already worn, here are ten suggestions for possible future Transformers spin-off movies.

Megatron: Dawn of the Decepticons: drawing heavily from both IDW’s Megatron: Origin and More Than Meets the Eye, this will be a biopic, essentially, of tyrannical baddie Big Megs. Although I know there’s a strong influence from The Fallen in Cinemegatron’s backstory, I don’t see how we can’t square this with the portrayal developed primarily by James Roberts. Megatron is a miner, struggling under a brutal regime on an off-world energon mine, who has the strength and smarts to lift himself and his co-workers out of bondage. But will he remain true to his principles or follow the advice of a mysterious old ‘bot (who turns out to be The Fallen)? Basically the tragic tale of a charismatic working-class leader breaking bad and becoming a monster. Could feature an Optimus Prime cameo – maybe as Orion Pax?

Last Stand of the Wreckers: a moderately-straight adaptation of the Nick Roche/James Roberts classic, one of the most beloved Transformers series of all time. Instead of Bumblebee’s delightful whimsy and Megatron’s tragic drama, this is a straight-up war movie. Obviously it’d have to be tweaked from the comic: no more Garrus-9 or Decepticon Purge. Perhaps tweak the last third to be a bit more like Rogue One or Seven Samurai; the Autobots decide to stay, and die, for a cause. I’d put some more mainstream ‘bots on the team, from the original cartoon and movie. Perhaps it could, like Bumblebee, even be set on Earth in the past, and end up being a story covered up by both the Autobots and Sector 7? That way you’d make it cheaper by having more humans and a little less CG. But the basic gist – an Autobot black ops squad is sent on a mission that goes very badly wrong and most if not all of them die whilst trying to work out what it means to be an Autobot in the midst of this war – should remain the same.

Windblade : whilst I don’t necessarily think the movieverse should adopt the “Thirteen Colonies” storyline from the comics – and I definitely don’t think they should adopt the “all the girls left” sausage-fest fudge that was required after Arcee was declared the “only” female Transformer, especially as Arcee herself and newcomer Shatter both feature in Bumblebee – I do like the idea of Windblade as some kind of ambassador or diplomat, travelling the universe. Perhaps she left Cybertron before the war really escalated (with besties Chromia and Nautica too, natch) to pursue peace elsewhere? Part flashback to pre-war Cybertron, part return-to-Earth narrative, it would be a great opportunity to focus on the often-sidelined female Transformers and have a positive feminist message. I’d have them team up with a now-adult Charlie and her estranged daughter... Verity Carlo. The baddies should be combiners, to go with the “Combiner Hunters” toy set.

Beast Wars: at the risk of causing controversy, I wouldn’t make this a straight adaptation of the popular cartoon. Not unless they want to meddle in far-flung futures or alternate timelines (although, er, see below...). Rather, I’d introduce the concept of “Beast Modes” that mimic organic creatures perfectly (like the “pretender” Decepticon in Revenge of the Fallen that looks like a sexy human girl, because of course she does). So my pitch is this: a lonely Autobot scientist, on a research ship that has more-or-less escaped the war (let’s make him Perceptor, for kicks) has developed this “beast mode” technology that hides Transformers in organic shells. His ship is attacked by Decepticons, but he rockets his subjects into space where they follow Prime’s signal and eventually land on Earth, befriending a young boy (younger than Sam or Charlie; let’s say about 12). But Decepticon hunters (I’d go for Carnivac, Snarler and Catilla – who later has a change of heart – all of whom have inorganic beast modes) follow. So it would share similar tropes with Bumblebee and the first Transformers, but with three or four cute animals instead of robots. This would skew young, perhaps even younger than Bumblebee.

Rodimus Prime: I know Hot Rod is in The Last Knight, but from what I hear he isn’t really representative of the character of Hot Rod/Rodimus from across other aspects of Transformers fiction. Regardless, this film isn’t about him: it’s about Rodimus Prime. Set in the future, it tells a Next Generation-style story of a human/Autobot alliance. Very much a sci-fi space opera, it would feature Rodimus going on a quest to discover the roots of a mysterious force that is attacking human colonies, and its apart links to an ancient Transformer legend. But is he abandoning Earth at its darkest hour to go on a wild goose chase through space? Rodimus must battle his own self-doubt as a leader, as well as a growing number of humans and Transformers who question the alliance. It would have a similar tone to your average Star Wars movie.

Wreck-Gar: Transformers films often have funny moments, but you’d never call any of them a comedy. Wreck-Gar is a comedy, Deadpool-style (but without the filth). A severely-damaged Transformer who crashes to Earth no memory and manages to rebuild himself in a junkyard, Wreck-Gar is a crazy, pop-culture-spouting dervish who just trashes every room he’s in, even though he’s not malicious or a bad guy. Indeed, he is chased by a trio of Decepticons (Swindle, Brawl, and Vortex) who are cruel and unusual (and Swindle wants recompense for a deal gone wrong). An all-out wacky comedy is something not often attempted by big-budget action movies; I’d even go whole hog and get Ward and Miller on board to shepherd the humour to the screen.

Starscream: we’re always focusing on the good guys! Well, here you go: a story about a bot who’s born to be bad. Starscream would be set in the past (naturally, since he’s dead now) and follows Megatron’s least-reliable lieutenant as he heads to Earth to look for Megatron during the time when he was in stasis underneath the Hoover Dam. I can’t remember the chronology, but maybe this could even be set in the late 70s/early 80s, with Starscream assuming a jet form more like his classic toy (and in that colour scheme, too). He’d be conniving, plotting, scheming, and essentially coming across like a giant metal version of Loki. Perhaps he’s playing a number of human “allies” off against one another, as well as some big Decepticons (Thunderwing? Tarn? Who haven’t we seen yet?) and even a troupe of Autobots he double-crosses. It could be darkly comic and incredible fun.

Hearts of Steel: Wild West Transformers! I mean, what’s not to love? Adapted from the IDW comic series (which was supposed to be out-of-continuity, but was so popular that writer John Barber retroactively incorporated it into the main Transformers timeline), this would need a bit of manipulation to change characters around (I don’t think Bumblebee should be in it, but given the often-contradictory nature of the movie timeline, I don’t see why we couldn’t bring back characters like Jazz, Ironhide, or maybe even Optimus himself). A rollicking steampunk adventure that hopefully would capture the freewheeling outback sci-fi tone of Back to the Future Part III, and hopefully not come across like another Wild Wild West.

Cybertron: I suppose this is a sort-of sequel to Megatron (see above). Set during the war, it’s a men-on-a-mission movie starring a young Optimus Prime (perhaps he could still be Orion Pax at this point). I don’t think we should worry too much about mythologies and intricacies of Transformer society the way James Roberts depicted it, but all the same they could do a lot worse than adapting his Shadowplay storyline, where Orion lead a team of misfit Autobots in an illegal heist to save the world. That kid of behind-enemy-lines vibe could give us a great Cybertronian war movie without wallowing in the grimdark explodey nature of Transformer combat. But especially if this was the movie where Orion earned his stripes and officially became Optimus, that might be nice. Like Megatron, of course, this would end up being an entirely CG affair.

Bumblebee 2: Energon Boogaloo? Look, the ending of the film – without wanting to give away spoilers – could be seen as neatly segueing into the 2007 Transformers film. One could imagine no additional adventurous meetings between Bumblebee and Charlie. But on the other hand, let’s not rule it out. Perhaps Bumblebee has been on Earth, dicking around, since 1987, and during that time he got up to more mischief with his first best human friend. Some covert Decepticon invasion requires him to break cover, or he needs some kind of human contact to spy for him, and oh look he goes back to Charlie. I’d skip forward a little bit, to around ‘91 or ‘92, slap a bit of early grunge on the soundtrack. See what happens. Just bring back Travis Knight.

So there we are. My ideas for ten possible Transformers spin-off movies. I didn’t really intend for this to turn into ten pitches with little mini-synopses; it was really meant to just be a quick fun game of “stories or characters who’d make a cool movie” but then I thought about it too hard, as I tend to do where Transformers is concerned. Hey, look, some of these films could even tie together! Megatron and Cybertron especially, but you could scatter seeds of stories or references among the lot. Anyway. Wishful thinking. But hopefully a film like one of these will roll out before too long (see what I did there?).

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

THE COMPLAINT that “we don’t build things anymore” is one of the oldest ideas in Trumpism. It’s also one of the few ideas to generate a policy with genuine bipartisan support in the president’s painful first year in office. Health care and the politics of engagement with Nazis may have left Washington more divided than ever, but who’s going to say no to infrastructure spending? The bridges are crumbling, and everyone loves a bridge. Tax reform may unite the Republicans, but when Donald Trump seems to want America to rediscover its vocation as a nation of builders, even his bitterest enemies are in on the racket. It’s not hard to understand the appeal of this macho revivalist fantasy. It fits the times. STEM is the hottest acronym in education, and the heroes of modern American business are all engineers of one variety or another. Meanwhile a new hegemonic rival has emerged across the Pacific, crudely caricatured as a nation of number-crunchers and builder-doers. The United States must keep pace, which means: more engineers, better engineers, more and better statisticians and scientists. Amid the West’s near-decade of failed experimentation with monetary policy, China’s rise has fed the idea that the road to durable growth will be dressed with new Parthenons. If they can do it, why can’t we?

Engineers enjoy a prestige in China that connects them to political power far more directly than in the US steel mills and highways have provided China’s ticket to prosperity over the last three decades, and the professionals who design and build them have controlled the levers of political power as well. Xi Jinping is an engineer, as were Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin before him. America, by contrast, has historically been governed by lawyers. That remains true today: there are 218 lawyers in Congress and 208 former businesspeople, according to the Congressional Research Service, but only eight engineers. (Science is even more severely underrepresented, with just three members in the House.) It’s unlikely that that balance will tilt meaningfully in favor of STEM-ers in the near term. But in another sense, the growing cultural capital of the engineers will inevitably translate to political power, whatever its form.

The engineering profession today is broad, much broader than it was in 1921 when Thorstein Veblen published The Engineers and the Price System, his classic screed on industrial sabotage and government by technocrats. Engineering has outgrown the four traditional branches (chemical, civil, electrical, mechanical) to include all the professions in which the laws of mathematics and science are applied to real-world problems. If math and science are the pure academic research branches of STEM, tech and engineering are its practical heart. The hackers and dreamers of Silicon Valley are all — if not by formal training, then by intellectual disposition — engineers. Interaction with the political world has grown in line with the profession’s expanding intellectual boundaries. As politicians of all stripes clamber to board the Silicon Valley rocket ship, the projects of the engineering profession, especially in consumer tech, are themselves now participants in the political process. Today’s engineers don’t just furnish the infrastructure of everyday life; they also build our most dynamic arenas of public debate (Google, Facebook, Twitter). In a way that was never the case for previous generations, engineering today is politics, and politics engineering. Power is coming for the engineers, but are the engineers ready for power?

It’s useful to reflect on Veblen’s work as the engineers enjoy this latest moment under the political sun. No American social critic has thought more carefully about the relationship between engineering and political power. Veblen used The Engineers and the Price System to outline a critique of financial capitalism that doubled as a call to arms for engineers to take control of the reins of government. In very basic form, his argument was that as capitalism had grown more complex, a class of financial managers had begun to exert control over businesses to the detriment of the engineers responsible for production. The job of these managers, in Veblen’s portrait, was to manipulate supply in order to juice profits. But engineering know-how was the indispensable alloy of production. This IP gave the engineers power. And engineers, Veblen argued, growing “uneasily ‘class-conscious’” as the “all-pervading mismanagement of industry” became plain, were “beginning to draw together and ask themselves, ‘What about it?’”. What about it indeed: Veblen predicted that engineers, formerly awestruck lieutenants of finance, would seize control of the country’s industrial system, ushering in a new era of planned economic management whose guiding principle would be the common good rather than private profit.

Alongside Wyndham Lewis’s 1931 portrayal of Hitler as a “celibate inhabitant of a modest Alpine chalet” more interested in vegetarianism than war, Veblen’s portrait of this approaching “soviet of technicians” — a political grouping as much as an economic one — ranks as one of the more comically inaccurate predictions of the interwar period. We all know what happened instead. Engineers did indeed throw off their habitual reserve and deference, but not in a spirit of class consciousness; they became dutiful capitalists themselves. The collapse of Veblen’s divide between the “financial managers” and the “industrial experts” led not to socialism but the birth of a new class of business-savvy engineer — what today we might call the “entrepreneur.”

But Veblen’s book was influential in other ways. It helped shape a certain idea of the engineer that took root throughout the 1920s: the engineer as a dispassionate problem solver, above the fray of ordinary commerce and politics, the engineer as capitalism’s savior. This carried over into the political domain and explains, at least in part, the rapture that greeted the election of Herbert Hoover, a mining engineer turned millionaire businessman and wartime humanitarian hero, as president in 1928. “The whole country was a vast, expectant gallery, its eyes focused on Washington,” wrote The New York Times a year later. “We had summoned a great engineer to solve our problems for us. […] The modern technical mind was for the first time at the head of a government. […] Almost with the air of giving genius its chance, we waited for the performance to begin.”

The performance, of course, would turn out to be a dud. Hoover’s great failing was his inflexibility. In Silicon Valley parlance, he failed to pivot: faced with a rapidly deteriorating economy, he stuck hard to his guiding political mantra of self-reliance and private-sector giving. By the time he overcame his aversion to federal intervention in the economy, it was all too late: output was shot, and so were his chances of reelection in 1932. Historians still argue over Hoover’s management of the economy through the early years of the Depression — a new biography by Kenneth Whyte argues for the reappraisal of his record as a policy maker — but they all agree on one thing: in the realm of human relations, Hoover was a dead squid. Here was a man who spoke only in “chill monosyllables,” as a contemporary observer put it, a man so rigid in his ways he went fly-fishing in a double-breasted blue serge suit. An engineer, Hoover once said at a campaign rally, could manufacture a waterfall much more beautiful than nature ever had. His listeners were appalled. Hoover himself did nothing to dispel the notion that he was more machine than man; on the contrary, he made it the cornerstone of his brand. “It has been no part of mine to build castles of the future,” he remarked in 1928, “but rather to measure the experiments, the actions and the progress of men through the cold and uninspiring microscope of fact, statistics, and performance.”

Chastened perhaps by their one humiliation in the White House, the engineers have not sought the highest office since. Hoover’s defeat marked the end of the first great flirtation between politics and engineering. For all the friendliness of these STEM-heady times, however, it’s unclear whether the engineers are now ready to stake another claim on political power. Peter Thiel, clammy and vampiric, had his hand held by President Trump, but as a profession the engineers have mostly sat the new president’s first 10 months in office out. (Thiel, it’s worth clarifying, is not an engineer, though he claims to speak for the engineering elite of Silicon Valley.) Of the current crop of celebrity-engineers, it’s Mark Zuckerberg whose engagement with the political world appears most meaningful. Partly this is by accident, since Facebook inadvertently became a central actor in the 2016 presidential election, but it’s also by design. Since the beginning of the year Zuckerberg has been on a tightly choreographed listening tour across the United States. He has rejected suggestions he’s using the tour as a platform to run for office in 2020 as emphatically as he’s refused to develop opinions on any of the public policy issues he’s confronted along the way. This is one education of a political naïf which contains, to date, no discernible narrative arc.

Zuckerberg has documented his travels, along with his thoughts on the news of each day, on his own Facebook page. Even on issues on which he’s taken a strong stance, such as immigration and refugee policy, Zuckerberg strains for an increasingly elusive political center ground. The day after the deadliest shooting in US history, he wrote: “It’s hard to imagine the loss from the shooting in Las Vegas. It’s hard to imagine why we don’t make it much harder for anyone to do this.” On climate change and energy policy, he hedged even harder: “I believe stopping climate change is one of the most important challenges of our generation. Given that, I think it’s even more important to learn about our energy industry, even if it’s controversial. Regardless of your views on energy, I think you’ll find the community around this fascinating.” If Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty were “tremendously excited with life” and after “girls, visions, everything” on their famous road trip, Zuckerberg is tremendously excited to not piss anyone off on his. Aw shucks, he seems to say on each stop throughout the country; let’s hear both sides of the argument out. Epistemologically, this is not far removed from Trump’s own “on many sides” apology for the Nazis demonstrating in Charlottesville. Did we ever think it would be otherwise? Zuckerberg’s political road trip has been every bit as disingenuously neutral as we should have expected from the man who thinks Facebook, the playpen of white supremacists, Russian disinformationists, and Pizzagate truthers, is “bringing the world closer together.”

There’s a simple way to explain these contradictions away: Zuckerberg is a businessman, not a politician, and his first priority is to his shareholders. This ignores, of course, the political nature of the company he runs. Zuckerberg can pretend he is above politics, a technocrat weighing both sides and implementing solutions through the cold and uninspiring microscope of facts, but politics will find a way to catch up with him eventually. The recent appearance by his company’s top lawyer before Congress to explain how Russian-sponsored election ads reached 126 million Facebook users during the 2016 campaign offered a stark illustration of social media’s politicization. But what was most telling about that appearance was that it was Facebook’s lawyer, rather than the CEO, who was dispatched to DC to face the music. When the major TV networks were called to the carpet in the aftermath of the 2000 election, they sent their CEOs. However seriously Facebook might say it’s taking the role it played in influencing the election — and it’s arguable the company is not even saying that (this Twitter feed is from Facebook’s head of VR, who seems to have been sent out to defend the company before the Congressional testimony. He did not seem contrite at all about the Russian interference) — Zuckerberg plainly considers himself above the fray, the impartial administrator of a cool tech gadget or, worse, a morally heroic guardian of free speech.

It’s possible, of course, that he simply doesn’t care. Zuckerberg’s willed blindness to Facebook’s role as a political actor is of a piece with his tin ear for human relations. In a Facebook Live post last month, Zuckerberg demonstrated a new app his company has been developing by taking viewers on a virtual reality tour of hurricane-struck Puerto Rico. Against a backdrop of flooded streets and ruined homes, Zuckerberg grinned and high-fived with Facebook’s head of social VR. “We’re on a bridge here, it’s flooded,” he told his 97 million followers at one point. “One of the things that’s really magical about virtual reality is you can get the feeling that you’re really in a place.” Responding to criticisms of the stunt, Zuckerberg began his apology: “One of the most powerful features of VR is empathy.” Empathy, in other words, comes from putting a box over your head that makes it impossible to see other humans. Okay, Mark. Whatever you say.

The caricature of the awkward genius engineer, skilled in solving well-defined problems but utterly lost amid human complexity and ambiguity and emotion, has proved remarkably resilient over the decades. Veblen painted the engineers as a “fantastic brotherhood of overspecialized cranks.” Hoover wore his inability to empathize almost as a badge of honor, casting it in quasi-mystical terms as a natural property of his profession. Subsequent generations of engineers have enthusiastically signed on to the stereotype that they’re cold automatons with no regard for human feeling; as one of the engineers interviewed for a 1991 NASA report on the Apollo program said, “I related to things.”

The cliché fits Zuckerberg as snugly as one of his custom-made $400 Brunello Cucinelli T-shirts. Years of experience have done nothing for his ability as an orator. In product launches and Facebook Live riffs straight to camera, delivered in that familiar vocoder counter-tenor, there’s an unchanging style to the Zuckerbergian sentence: it begins with a programmatic smile, races through four or five words of world-embracing banality, gets stuck, short of breath, grinds and lurches forward again, all syncopation and no beat. It’s like watching a machine learn to be happy. That might be enough to get the crowds going in Silicon Valley, but it’s hard to see Zuckerberg prospering amid the retail hug-and-handle of national political competition. Bloodless technocrats might fare well in municipal politics (see Bloomberg, Michael) but the national stage needs its political performers to show emotional intelligence, or at least — here comes the necessary Trump-mandated qualification — a flair for the theatrical. Zuckerberg has neither.

It’s instructive to look at Zuckerberg’s foray into the public sphere, however “apolitical” he may portray it, within the context of Veblen, Hoover, and the first failed marriage between the engineers and power. You don’t have to look hard to find, in Zuckerberg’s missteps, traces of the very things Veblen mischaracterized about engineers — their greed and lack of fealty to the public good. Zuckerberg also gets wrong what the engineer-president got wrong in power — an overweening belief in the power of numbers to move minds, in the disavowal of feelings. Shared by all three figures is a basic failure to understand the political process: the body politic is not a machine, and the complexity of power in human society is different from the complexity of computers. It’s perhaps unfair to make an example of Zuckerberg (“not all engineers,” et cetera) but if his experience is any indication, the engineers are as far from taking political power today as they ever have been in the decades since Hoover shuffled out of the White House, a crying wreck.

In another sense, though, they have made power come to them. The language of engineering, and software engineering in particular, has become the default language of entrepreneurship. Whereas in the past the vocabularies of law or finance or management consulting were the guiding idiomatic template for capitalism, to “do” business today you have to think, at least at some level, like an engineer: setting a problem, defining its rules and properties, applying logic, prototyping and testing solutions, iterating, testing again, and continuing on the virtuous engineering feedback loop until perfection is at hand. The principles of technocratic efficiency and rule-by-expert that both Veblen and Hoover supported, albeit in different ways and to different ends, are now the mood music of modern capitalism. Fact, statistics, and performance have won the day. We’re all data-driven now; intellectual authority comes from mastery of the numbers.

Zuckerberg is both the beneficiary and the expression of this historical movement. The Facebook founder’s lack of empathy is not, as the engineering cliché would have it, a function of super-intelligence: an inability to see things within context and from the perspective of others is in many senses the essence of stupidity. But the engineers, collectively, have come to dominate the conversation about what it means to be “smart.” Intelligence today inheres in their type of intelligence: data-focused, quantitative, rationalistic, and feeling-free. If you’re not STEM, you’re dirt — or useful only as a vassal for the refinement of engineering projects, which is much the same thing. On the historical evidence, this engineer’s form of intelligence is wholly unsuited to solving the most complex problems of government; tech smarts do not port easily to politics. However violently Silicon Valley pushes the story that it’s here to fix things for all of us, building an algorithm and coming up with intelligent ways to improve society are not the same thing. The triumph of the engineers is that they’ve managed to convince so many people otherwise.

This victory is more than simply economic or mechanical; engineering has also come to permeate the language of politics itself. Zuckerberg’s doe-eyed both-sidesism is the latest expression of the idea, nourished through the Clinton years and the height of the evidence-based policy movement, that facts offer the surest solution to knotty political problems. This is, we already know, a temple built on sand, ignoring as it does the intractably political nature of politics; hence the failure of “figures” and “facts” and “evidence” to do anything to shift positions on gun reform or voter fraud. But it’s a temple with enduring bipartisan appeal, and the engineers have come along at just the right moment to give it a fresh lick of paint. If thinking like an engineer is the new way to do business, engineerialism, in politics, is the new centrism — rule by experts remarketed for the innovation age. It might be generations before a Veblenian technocrat calls the White House home, but no presidency can match the power engineers already have — a power to define progress, a power without check.

¤

Aaron Timms is a Brooklyn-based writer. His writing has appeared in the Guardian, The Outline, The Daily Beast, and The Week. He tweets at @aarontimms.

The post The Engineers and the Political System appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2B4HnWC via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

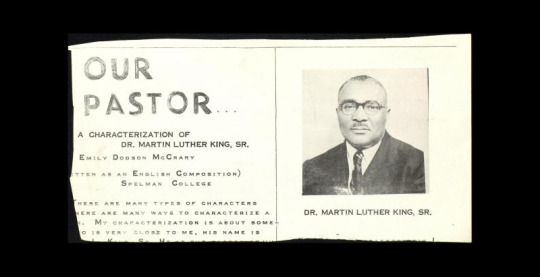

(via The Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. on His Son’s Legacy)

*trigger warning: violence*

As the 1960s unfolded, the great well of passion stored up in this country for so long simply spilled over. M.L. and A.D. were moving the South with their efforts and those of the young men and women who marched America far beyond its own expectations for a time. And whether the location was Albany, Georgia, or Birmingham, Alabama, or Chicago, Illinois, the message was clear. The cause of integration in America was served by the nation’s aristocrats, farmers and students, by workers and preachers, men and women, young and old. The costs were accepted when they came and they were often very high. But we moved through.

Ivan Allen, who succeeded Hartsfield as mayor, had the courage to stay in office for a couple of terms, and it took courage through the 60s. The Voters’ League was with him and with Sam Massell, the city’s first Jewish mayor, who succeeded him. And coming into the present, Atlanta has a black mayor, Maynard Jackson, whose grandfather, John Wesley Dobbs, and I labored together in the 30s and 40s to make it possible for our people to vote. I’ve supported that line of succession with the long-term feeling that it may be the most interesting series of city officials in the nation’s history. So I have lived in Atlanta, and go on doing so.

I also lived to be at Oslo, Norway, to bear witness when M.L. received the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1964. And I prayed on the plane trip over there that the Lord would keep me humble, the son of a sharecropper and father of a man who, at the age of 35, had been presented the most prestigious of world awards. God surely had looked down into Georgia. And He must have said, Well, here are people I will give a mission and see how well they can carry it out. And I felt He must have looked down into Oslo, Norway, and simply said, Yes, they have shouldered the weight part of the way. A people had been led by a young man who could have found comfort elsewhere, yet stayed where he was needed, bearing witness. And as M.L. stood receiving the Nobel Prize, and the tears just streamed down my face, I gave thanks that out of that tiny Georgia town I’d been spared to see this and so much else. M.L. was my co-pastor now, and A.D. would soon be joining us in serving Ebenezer. I knew the movement was far from finished with its work, but I did feel M.L. had given so much, reached so deeply inside himself to be up in the front lines, where the glory was thought to be, but where danger held the real dominion.

Killing is a contagion. It begins, then rushes like fire across oil, raging through emotions out of control. America will have to remember the early 60s when the guns came out, when small children were blown to pieces while in church, and the blood seemed destined to flow until it became a river. The nation seemed to lose its way, as though it stumbled for a while through some dense forest where nothing could be seen clearly. How could we not have realized what was coming when those four young girls were killed by the explosion at their church in Birmingham? Was it not any clearer when civil-rights workers began disappearing, and when Medgar Evers, over in Mississippi, was shot down without any real concern about punishing the man who supposedly murdered him? How could a nation have not understood the terrible path it was walking when the President of the United States could be gunned down while riding in an open car through an American city?

The turmoil continued. The 60s were a time of battle for jobs and housing and the winning over of whites, who came now to understand how their lives, too, were being bent out of shape.

What we learn, with God’s help, is that there is no safety. Therefore, there can be no danger we are not willing to face. A great passion stirred this nation in the 60s, bringing violence and rage with it, but focusing on the hypocrisy that was at the root of America’s racial condition. Our struggle against that racist part of the nation’s personality was recognized, in some instances, more quickly and with a great deal more understanding in other parts of the world than it was at home.

When M.L. asked me to join him in 1964 at Oslo for the Nobel ceremonies, all over Europe folks had been clearly aware of what my son was trying to accomplish against enormous odds. But in the United States, a campaign to destroy his leadership was conducted within the government. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, made no secret of the fact that he held M.L. and his work in contempt. And the Civil Rights Movement received little active support from church leaders, many of them close enough to the struggle to see how important M.L.’s nonviolent protests had become among young people. When he was in jail, there were those who turned their backs, who criticized and rebuked him. He carried on.

It was a time when strong churchmen needed to reach out to embrace the American public as it huddled against its pain and tried to pretend that everything was still under control. We had moved to establish the sense of freedom any people must have to remain civilized.

There could be no real separation between exploiting a man because of his color and taking advantage of his economic condition to control him politically.

I had entered civic affairs as a young man because I thought everyone wanted a better world and that nobody would have one if I didn’t put a shoulder to all the wheels that turned justice and dignity. A preacher, as I understood the term, was called for life. And there was a wondrous harvest in those fruitful years. But I could hear the ticking that was fast replacing the American heartbeat in our daily lives. And as M.L. expanded the movement, I became more and more concerned and less and less able to get him to pull back even for a time. Bunch was deeply affected, of course. She grew ever more apprehensive as her sons became rooted in the struggle and the cause.

By 1968, there was great anxiety throughout our family. No matter how much protection of any sort a person has, it will not be enough if the enemy is hatred that cannot be turned around. Not even the forces of law can control such hatred in a society. When evil is organized, it becomes a cup more bitter than the one given Jesus . . .

In April 1968, my sons went to Memphis to help organize a struggle by the city’s sanitation workers to achieve better wages and working conditions. I wondered about M.L.’s involvement in this, whether or not he was spreading his concerns and his energies too thin. But again he was right. There could be no real separation between exploiting a man because of his color and taking advantage of his economic condition to control him politically. Exploitation didn’t need to be seen only in terms of segregation. It involved all people, white and black, in the continuing human drive toward freedom, toward personal dignity within a just society. In Memphis, M.L.’s joint efforts with the workers brought out the old charge that he was, inside, more Communist than Baptist, which may have been the silliest thing anybody ever said about any person in America.

M.L. had been able to convince his brother, who was extremely skeptical in the beginning, that he too could make a difference in the kind of America that would enter the 21st century. The nation could be changed. The cracks in the armor of racist attitudes were visible all over the South. Maybe the time had been ripe before, but M.L. could see that now was an excellent moment in history to move a nation beyond itself. He sensed that Americans would respond emotionally to what he was now doing, that their passions could be cooled, then turned around into a force that would make the country into the place it should always have been. We have the resources, he would explain to me. We have the means, and the human energy needed is at its peak. . . .

The tension of those months took a heavy toll on Bunch, who was always aware of the pressure both the boys were under in their daily lives. The sound of a telephone, our doorbell ringing, any call that brought with it some news, edged up on us like a series of loud, sudden alarms. M.L. knew he had to share with his mother the changing nature of events as they involved him. Each moment he was away, out of touch with her, became an eternity of waiting for the next indication of any kind that he was all right.

He came to Atlanta and had dinner one evening with his mother and me. Some of the things he’d told me earlier came as no surprise, but both of us understood how difficult the information was going to be for Bunch to handle. Several reliable sources, both private and from within the federal government, concluded that attempts would soon be made on M.L.’s life. Money was involved. Professional killers were being recruited.

After dinner, the three of us sat out on our patio and enjoyed the late-setting sun of a warm, clear evening. Had I chosen M.L.’s words, perhaps I wouldn’t have been so blunt. He felt, though, that out of respect for his mother, he couldn’t be less than candid with her. “Mother,” he said, “there are some things I want you to know.”

“I have to go on with my work, no matter what happens now, because my involvement is too complete to stop.”

She didn’t want to listen, not then, on that quiet Sunday when it was so good to laugh about childhood, and remember tears easily replaced with laughter back when everything seemed so much less dangerous. “There’s a chance, Mother, that someone is going to try to kill me, and it could happen without any warning at all.” M.L. said this quickly, then stood up and walked to the far end of the patio. We sat silently, knowing that for this moment at least there couldn’t be any words. The same emotions that caused Bunch and me to urge M.L. to leave the movement more than ten years before were all still there. But saying these things now could bring no relief, only an intensity to the suffering we all carried. The great weight of that, I still believe, came from the certainty all of us had that what M.L. had chosen to do was unquestionably right.

We had been aware of the dangers, each out of our own experiences with the South we knew—M.L., his mother and I. A time had come. To avoid it was impossible, even as avoiding the coming of darkness in the evening would have been impossible. But word was moving through our part of the world. People were reporting conversations overheard in restaurants, in taverns, on street corners, that indicated serious efforts to plot against M.L. as a leader of this movement that was changing so much in America so quickly. Police departments had been alerted. The talk of hired killers being on the loose and following M.L. was now past the stage of rumor and hearsay. Police officers who had never been in sympathy with our cause were nevertheless concerned about anything happening to my son in one of their towns or cities. It simply wouldn’t have looked good, I suppose, for all these law-and-order advocates to be unprepared for lawbreakers whose intention was to commit murder.

“But I don’t want you to worry over any of this,” M.L. said, returning to his mother’s side. “I have to go on with my work, no matter what happens now, because my involvement is too complete to stop. Sometimes I do want to get away for a while, go someplace with Coretta and the kids and be Reverend King and family, having a few quiet days like any other Americans. But I know it’s too late for any of that now. And if mine isn’t to be a long life, Mother, Dad, well then I respect that, as you’ve always taught us to respect it as God’s will.”

We ached when he left that evening, deep inside, and though we tried to comfort each other with small talk about neighbors and church folks and even our earliest hours together, nothing could remove the unspoken pain we were sharing.

From Daddy King. Used with permission of Beacon Press. Copyright © 1980 by The Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr.

0 notes