#but it is indeed a colonial power that still enforces rule over other people

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

French Politics Update

Since the 2024 French elections earlier this year, we left off with a more balanced National Assembly. Left-wing politicians became the highest population at 188 seats with centrist Emmanuel Macron still the president. The centrist party is not far behind with 161 seats and the right-wing party with 142.

Many networks at the time discussed the expectation of a hung parliament, as no one party holds the 289-seat majority.

Some things stay the same. In July, the National Assembly voted to keep centrist party member Yaël Braun-Pivet as speaker, winning by 13 votes. Additionally, many people have called for Macron to step down as President, but he will likely stay for the rest of his term until 2027.

New PM

On the other hand, there have been major changes. Prime Minister Gabriel Attal resigned in July, and was replaced by Michel Barnier in September. He is a conservative, the leader of the 2016-2019 Brexit negotiation, and his appointment was met with much criticism from the left-wing parties.

Days after his appointment, over 100,000 people participated in protests across France. Many people view President Macron’s PM choice as disruptive to democracy, as the PM is most often chosen from the dominant National Assembly party.

Macron states that he made this choice based on the belief that Barnier seemed the most capable of dealing with political deadlocks, as is expected of the Parliament with no party holding majority.

I have to wonder, though, if this was also out of spite for the left-wing parties winning more seats than his centrist party. Barnier’s politics are expected to rely on joint support from the centrist and conservative parties. If the right or center opposes him on anything, he almost certainly will face loss after loss with his proposed policies. Will this lead France backward after the left finally gained some political power?

Barnier’s Address

Barnier delivered his first parliamentary address on Tuesday, October 1st. Summarily, he emphasized the hazard of French finances and debts, and the environment.

France is more than 3 trillion euros in public and environmental debt, which Barnier addresses first. His goal is to bring the deficit down from 6% of the national GDP to 5% in 2025, with the goal of under 3% by 2029.

His outline for achieving this is reducing spending, being more efficient in government spending (addressing corruption and unjustified spending), and taxes. He phrases higher taxes as a temporary measure, and states that large companies as well as the richest and wealthiest French people will be asked for exceptional contributions.

Barnier also addresses environmental debt. He plans to continue reducing GHG emissions, and for France to be more active in the EU and in the Paris Agreements, which push for countries to collectively act against climate change. He also mentions encouraging industry transitions in energy and recycling, encouraging nuclear energy development, and developing renewable resources of energy more, like biofuels and solar energy.

He has also conceived of a large national conference to act on the matter of water, the scarcity of which is an imminent issue for France.

Additionally, he plans to propose a yearly day of citizens consultations. In his idea, doors will be open for citizens for people of all levels of government to ask questions and start discussions and debates on various topics.

Another noteworthy statement from Barnier is that the pension reform bill voted on in 2023 might have to be changed, which received a loud reply from the audience.

As someone living in a country where an entire political party is built on denying factual evidence and realities, it is surprising to hear someone who does not deny climate change, and calls for equitable taxes to address debt.

About 30 minutes into his address, though, New Caledonia comes up. This is more in line with expectations of conservatives. New Caledonia is still a colonized territory of France, and a recent bill from Macron was going to disadvantage native Kanak people for the advancement of French loyalists on the archipelago. After fatal protests, the bill has been suspended before ratification, likely to be readdressed in 2025.

Also in conservative spirit, Barnier calls for stricter immigration policies in effort to meet ���integration objectives”. France faces a cost-of-living crisis and an affordable housing shortage that has buttressed the right’s stance on needing stricter border measures.

Le Pen Trial

Also straining politics, especially for right-wing support, is recent news about popular right-wing figure Marine Le Pen.

On September 30th, Le Pen faced charges of embezzling European Parliament money. The right-wing party Rassemblement National is accused of filing false employee records in order to improperly use funds to pay members of the party. Le Pen is one of many senior party members involved in the alleged embezzlement.

This trial is expected to go on for seven to nine weeks, so the final outcome is some time away. But for now we can expect this will have negative impacts if Le Pen still vies for presidential election in 2027. It will likely also decrease citizen’s trust in the conservative party’s ability to make responsible economic decisions.

If found guilty, Le Pen and the other defendants could face up to ten years in prison and lose the eligibility to run for office.

After the 2024 shock vote instigated by President Macron, the French National assembly gained a left-leaning majority, though not enough for an automatic 289-vote majority. In most cases, this would mean a left-wing Prime Minister as well as a left-wing president, though that’s because the presidential vote is usually shortly after that of the national assembly.

Contrarily, Macron went with a conservative candidate that he believed to be stronger for the job. This increases the political unrest in the country, and increases the likelihood of delays and blockages in legislation development.

While the conservative Prime Minister has stated many intentions that people in the U.S.A. might call left-leaning, regarding climate change and tax targets, his appointment has upset many. His views on immigration, especially, contrast with most left-wing groups who want integration and safety for others. Overall, this decision from Macron calls into question his loyalty and dedication to the wants of the French people.

Additional Resources

1. New Prime Minister

2. Barnier on Borrowed Time

3. Le Pen on Trial

4. Barnier Address

5. Barnier Address Summary

#france#french politics#prime minister#emmanuel macron#french election#article#research#resources#environment#climate change#news#renewable energy#long post#yeah I look into France because I studied French and it's interesting#but it is indeed a colonial power that still enforces rule over other people#Michel Barnier#marine le pen#Going to look into actual crime statistics and immigration next#since that's all misinformation in the states

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just read Scott Alexander’s post on “conflict theorists” vs. “mistake theorists” and, hmm. I have several thoughts. First, to summarize the concept for anyone who hasn’t seen it before: Alexander links to a reddit post by user u/no_bear_so_low, who originated the idea, saying

There is a way of carving up politics in which there are two basic political meta-theories, that is to say theories about why different political ideologies and political conflict exist. The first theory is that political disagreements exist because politics is complex and people make mistakes, if we all understood the evidence better, we’d agree on a great deal more. We’ll call this the mistake theory of politics. For the mistake theorist, politics is not a zero-sum game, but a matter of growing the pie so there is more for everyone. The second theory is that political disagreements reflect differences in interests which are largely irreconcilable. We’ll call this the conflict theory of politics. According to the conflict theory of politics, politics is full of zero-sum games.

u/no_bear_so_low claims that both the far left and far right are more amenable to conflict theory than liberals are, who lean more towards mistake theory. Alexander seems to agree, though in his own post he’s speaking mainly about Marxists in particular. He summarizes the concept as follows:

To massively oversimplify:

Mistake theorists treat politics as science, engineering, or medicine. The State is diseased. We’re all doctors, standing around arguing over the best diagnosis and cure. Some of us have good ideas, others have bad ideas that wouldn’t help, or that would cause too many side effects.

Conflict theorists treat politics as war. Different blocs with different interests are forever fighting to determine whether the State exists to enrich the Elites or to help the People.

In addition, Alexander subdivides the categories further into “hard” and “soft” versions:

Consider a further distinction between easy and hard mistake theorists. Easy mistake theorists think that all our problems come from very stupid people making very simple mistakes; dumb people deny the evidence about global warming; smart people don’t. Hard mistake theorists think that the questions involved are really complicated and require more evidence than we’ve been able to collect so far [...]

Maybe there’s a further distinction between easy and hard conflict theorists. Easy conflict theorists think that all our problems come from cartoon-villain caricatures wanting very evil things; bad people want to kill brown people and steal their oil, good people want world peace and tolerance. Hard conflict theorists think that our problems come from clashes between differing but comprehensible worldviews.

So what do I think about all this?

Well, it seems to me that this framework is (a) a fairly reasonable descriptive dichotomy, in the sense that, yes, a lot of people do genuinely seem to fall into one of these two camps, and (b) a horrible dichotomy on which to base any prescriptions about political meta-theory, in that these are both awful (and obviously wrong) ways to think about the world. Now, Alexander doesn’t explicitly give any such prescriptions, but he does describe SCC as “hard mistake theorist central”, and generally speaks of mistake theory in approving terms, while speaking of conflict theory in disapproving ones. I think this is bad.

At a base level, my problem with both these “theories” is that they’re, in some sense, just too optimistic.

I agree, for example, with the hard mistake theorist sentiment that the world is full of extremely challenging technical problems, that these problems can be the source of real human suffering, and that the only way to address these problems is through data collection and empirical analysis and hard technical work. And I agree that this will often produce unintuitive conclusions, that run against people’s gut sense of what the right policy might look like. I agree that the state is diseased. I do not agree that “[w]e’re all doctors, standing around arguing over the best diagnosis and cure.” People, it turns out, often do have genuinely different and irreconcilable values, and genuinely do envision different ideal worlds. In addition to that fairly mundane observation, there genuinely are a lot of bad actors, who are just in the game for their own benefit. The world is full of grifters, schemers, and petty (or not so petty) tyrants; on an empirical level that’s just not something you can deny.

On the other hand, I agree with the easy conflict theorist sentiment that, e.g., “bad people want to kill brown people and steal their oil.” There’s plenty of pretty immediate proof of that to be found if you look into the history of colonialism¹, or the slave trade, or US foreign election interference in the twentieth century. Actually, just so I’m not pissing anybody off by only mentioning “western” examples, I’ll include the Khmer Rouge and the Holodomor and comfort women and uh, you get the picture. For god’s sake, the Nazis really existed, and yeah, they really believed all that Nazi shit. In retrospect they may seem like implausibly evil cartoon villains, but in fact they were real flesh and blood humans, just like the rest of us. You think that was just a one-off?

And on a much more mundane note, sometimes (actually, very very often), ordinary people just have incompatible ethical axioms. Sometimes people have genuinely different values, and there are no rational means to sort out which value-set to choose. I suspect this is at least part of the reason for the rationalist community’s skew towards mistake theorizers, in that their favored intellectual tool has more-or-less nothing to offer when it comes to selecting your values (=ethical axioms, =terminal goals, etc). I mean, of course rationality is good for diagnosing contradictions in your value set, but it can’t tell you how to resolve those contradictions. That’s the domain of intuition, empathy, and aesthetics, were data cannot light your way.

However, I do not agree with the conflict theorists’ underlying sentiment that if “the good people” were just in charge, everything would be better. After all, there are all those pesky technical problems with unintuitive solutions getting in the way, requiring all kinds of expertise and thorough empirical study and uh, plenty of them might not even be solvable.² This is a huge deal. It’s incredibly easy to have the best of intentions and still make horrible mistakes by virtue of just... happening to have the facts wrong. Not through malice, or self-interest, or even some nicely-explainable sociological bias like white fragility or whatever. Just because problems are hard, and sometime you will fail to solve them. Even when people’s lives and livelihoods are at stake.

Here’s a handy latex-formatted table for your comprehending pleasure:

lol, we live there.

So this all sounds a bit pessimistic and, well, I suppose it is. I think we have a responsibility to acknowledge the gravity of our situation. We could, conceivably, live in a world that was structured according to either the conflict theorist’s vision or the mistake theorist’s vision, but we don’t. We live in a much scarier world, and if we don’t face that terrifying reality head-on, we’re not going to be able to overcome it.

Now, in general, I’d say I spend a lot of my internet-argument-energy-allowance trying to persuade [what I perceive to be] overly conflict-theorizing leftists in the direction of a greater recognition of the genuine technical difficulty of the problems we face. It's probably worth making a separate post about why I think a “denial of unintuitive solutions” is so common on the left, but I’ll just mention here that I think it relates to what I once jokingly called the “Humanistic gaze”. That is, the bias to view everything quite narrowly through the lens of the humanities, and to view all problems as fundamentally sociological in nature. When the world is constructed entirely by humans and human social relations, there’s a level at which nothing can be unintuitive. After all, an intersubjective world must ultimately be grounded in subjective experience, and subjective experience is literally made of intuition.

I usually don’t spend much time pursuing the dual activity (trying to argue liberals out of [what I perceive to be] an overly mistake-theorizing perspective). This is largely because, well, I think the optimistic assumption that mistake theorists make —that most people have basically compatible goals, and that relatively few people are working out of abject self-interest or hatred or whatever— is so obviously false that it doesn’t warrant as much genuine critique as it warrants responding with memes about US war crimes. The principal of charity is best extended to ideas, not people or institutions. You can take the neocons’ arguments seriously without extending charity to the neocons as agents.

The post concludes with Alexander writing

But overall I’m less sure of myself than before and think this deserves more treatment as a hard case that needs to be argued in more specific situations. Certainly “everyone in government is already a good person, and just has to be convinced of the right facts” is looking less plausible these days.

And uh, yeah. Indeed.

So, in conclusion: is politics medicine, or is it war? No, it’s politics.

There are disagreements, and conflicts of interest, and coalition building, and policy-wonkery, and logistics. There is, as with anything involving the state, the implicit threat of violence. (That’s where the state’s power comes from, remember? Whether it’s their power to tax, or their power to enforce individual property rights to begin with. Their power to regulate or build infrastructure or legally construct corporate personhood or whatever. There’s more than a bit of game theory involved, sure, but the rules of the game are set through the armory.) Every scholarly technocrat with double-blind peer reviewed policy suggestions still ultimately just decides who the guns get pointed at, if at several layers of abstraction. Every righteous people’s vanguard is still bound by the mathematics of production and the dynamics of a chaotic world. There are no easy solution, not conceptually easy nor practically easy. And unless we recognize that on a very deep level, we have no chance of fixing anything.

[1] I’d quote my go-to example here, of the truly ghastly stories relayed to linguist R. M. Dixon by the Dyirbal people of Australia about their subjugation at the hands of white settlers, but unfortunately I don’t have his book with me at the moment. Also this post would require several additional trigger warnings.

[2] I mean, after all, there are only countably many Turing machines, and the set of all languages with finitely many symbols has cardinality 2^(aleph_0)!

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

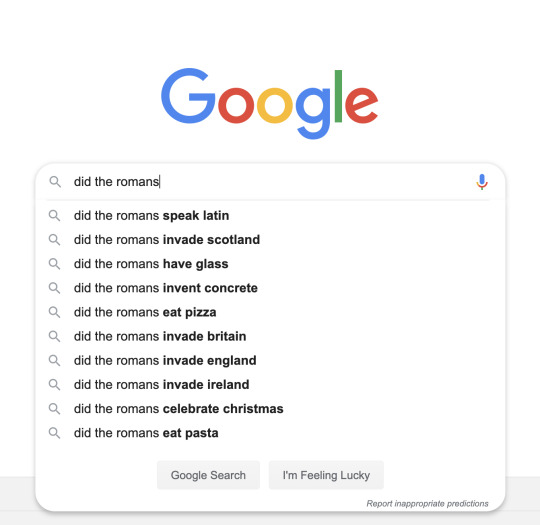

‘Did the Romans and ancient Greeks ... ?’

Google autocomplete is a gem and a curse. Inspired by @todayintokyo’s post on questions about Japan, I thought I’d have a look at what people are asking about Rome and classical Greece and, wow...

Christmas holidays leave a lot of time for milling around, so I’ll answer them in case anyone’s interested. (Please forgive me if any of this is incorrect/incoherent, it’s nearly 11pm as I’m writing this lol)

Did the Romans speak Latin?

Yes, Latin was Rome’s (and the Roman Empire’s) official language! Of course, many Romans or foreigners in Rome spoke other languages for the sake of communication, trade and education - Greek was particularly popular among the nobility - but Latin was what they all had in common.

Did the Romans invade Scotland?

Long story short, no. They tried, failed, and built Hadrian’s Wall to keep the ‘barbarian’ Gaels out - southern Britain was already too cold and muddy for the temperate Romans, not much point in losing more lives over more mud.

(Hadrian’s Wall was what inspired Game of Thrones’ The Wall, as confirmed by G.R.R. Martin himself, but Hadrian’s was nowhere near as high, thick or long.)

Did the Romans have glass?

Absolutely! In fact, their skill with it was much more artistic and masterful than the average glassmaker today, just search ‘roman glassware’ here on Tumblr or on Google images to see what I mean.

Did the Romans invent concrete?

Yep! It’s famed for its durability, which is due to its contents of volcanic ash (Pompeii flashbacks), lime and seawater. The seawater reacted with the ash over time to give it its strength and anti-cracking nature.

In fact, the Roman method was so effective that it lasts for far longer than modern concrete (modernity/Westernisation =/= progression, it seems) and scientists today are trying to find ways to revitalise it.

Did the Romans eat pizza? / Did the Romans eat pasta?

Sadly not, only later Italians did. Their empire deserved to crumble for not inventing either smh.

Did the Romans invade Britain? / Did the Romans invade England?

They did indeed in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and they only began to withdraw in the late 300s when the city of Rome was being threatened by a Germanic tribe called the Visigoths.

Did the Romans invade Ireland?

No. Even now, archaeologists have no idea to what extent they communicated or even knew of each other.

Did the Romans celebrate Christmas?

Emperor Constantine only began converting the empire to Christianity from AD 313 (they had been pagan previously), and the earliest evidence we have of Romans celebrating Christmas was in 336 AD, very late in Roman history. Throughout most of Roman history, therefore, no they did not celebrate Christmas.

(They did have a festival which was similarly important and similarly timed (mid-December) called the Saturnalia. It also involved communal partying, gift exchanges and a general spirit of liberty (e.g. slaves could order around and punish their masters) - it was one of the most anticipated festivals of the Roman calendar. However, the purpose was very different: it was to worship the pagan god Saturn, the father of god-king Jupiter and the previous ruler of the world before its occupation by humanity. Namely, the festival marked a return to the ancient ‘Golden Age’ in which nature was dominant, peaceful and uncorrupted.)

Did ancient Greece have emperors? / Did ancient Greece have kings?

No emperors, traditionally Greece was comprised of city-states ruled by kings (or theoretically by the dēmos, the people, if you were Athens). Under Roman occupation it did answer to Rome’s leaders (consuls, then later emperors), but the idea of emperors was much more late-Roman than Greek.

Did ancient Greece celebrate Christmas?

Nope. It was originally pagan and did not celebrate any Christian holidays until a) it was conquered by Rome b) Rome later converted to Christianity, thus enforcing it on the rest of the empire. However, this conversion point was so long after the ‘heroic’ and ‘classical’ periods of Greece that by the time it did become mostly Christian, it was no longer ‘ancient Greece’ in the same sense.

Did ancient Greece have electricity?

Y’all are asking the real questions out here, that’s for sure lmao.

Nope, electricity wasn’t used anywhere as a power source until Thomas Edison’s studies about two thousand years later.

God though, a good ol’ GPS would have saved Odysseus a lot of trouble.

Did ancient Greece and Rome overlap?

Oh, nelly...

Greece predated Rome by at nearly a thousand years, but Greece’s and Rome’s histories together lasted for centuries, even before the latter conquered the former. It’s why they are studied together as one field of academia. Many Italian settlements were in fact Greek colonies. Classical Greek helped shape Latin. Much of Roman religion was inspired by that of the Greeks. Many Greeks could speak Latin and many Romans could speak Greek. Roman art, philosophy and architecture was particularly fascinated by that which was Greek - to put it in meme format, the crab is Roman culture and the crocodile is Greek culture. And these are just the absolute basics, entire tomes have been written on Greece’s and Rome’s somewhat symbiotic relationship.

TLDR hell yes they did.

Did ancient Greece have a flag? / Did ancient Greece have a constitution?

Nah. Although history often refers to Greece as one country, one culture, it was more a collection of independent city-states with their own identities and constitutions.

They all had three things in common: religion (+ the moral/social codes which came along with it), language, and (in most cases) enemies from abroad - therefore in later centuries, as well as their city-based nationalities, they did all call themselves the Hellenes. If you were a fellow Hellenic, you’d be able to work and live in other Greek cities with less trouble than if you were to try, say, in a ‘barbarian’ land such as Persia. Greeks were civilised; everyone else was an uncultured brute. Hence, their sense of unity was more from fear of the outside, from xenophobia, than from internal harmony.

Because of this, there was never an altogether complete sense of assimilation. Different cities had distinct dialects, favoured different gods/cults within the wider Pantheon, often warred against each other (especially Athens and Sparta, whew), fed their own specific cultures and law-sets and reputations. Nationality and citizenship in that age were not really about country or region, the world was just too small for that. You wouldn’t say ‘Hi I’m Phoebe and I’m Greek’, you’d say ‘Hi I’m Phoebe and I’m from the city of Halicarnassus.’ The closest analogy I can really think of is the cities in the dystopian series, Mortal Engines.

So no, they didn’t have a single flag or constitution. There was just not enough unity between them all.

Did ancient Greece trade?

Initially I was going to wave this off as a silly question because ‘hurr durr everyone trades’ but ACTUALLY.

Along with the rest of the eastern Mediterranean, Greece had its own Dark Ages between the fall of its early society (aka Mycenaean Greece) and the rise of Homeric-style poetry and culture, i.e. between the 1100s and 700s BC. Communication in general was absolutely awful: there were no great armies, no great cultural progressions, and yes, no substantial trade. The fact that Greece was then feeling down in the dumps also discouraged foreign trade.

It took the bard Homer’s influence to get people to start thinking, creating, travelling and thus mass-trading again - this sudden surge in activity eventually led to Greece’s Classical Period, i.e. 4th century BC, you’ll probably imagine gleaming Athenian pillars. Increased thinking and culture led to increased politics/nationalism, increased p/n led to increased warring and military action, increased warring improved transport and communication, and WHOOSH suddenly trade took off.

So basically, Mycenaean Greek trade was good (as far as we can tell), Dark Ages Greek trade was shocking, Classical Greek trade was quite literally revolutionary.

Did ancient Greece have lions?

Yep! However, they weren’t like the sub-Saharan lions you’re probably imagining right now - those are Panthera leo, but the Eurasian lions that would have been in Greece were Panthera spelaea.

Nevertheless there were indeed lions and they played a huge role in Greek mythology and literature. The Nemean Lion was the first of Hercules’ Twelve Labours; Homer, the trendsetting legendary lad that he was, created a trope of comparing something innocent and vulnerable to something vicious and savage and desperate by using the analogy of a lamb and a hungry lion.

Did ancient Greece have a democracy?

Nope, only one city named Athens did. Don’t get me wrong, it was at the time and still is a big deal considering it hadn’t been done before, BUT there are three important things to note:

It was ONLY Athens which had a democracy - every other Greek city kept their kingships.

The Athenian democracy wasn’t what we’d call democracy. Only free, Athenian-on-both-sides men could vote and participate in local politics - this left out all slaves, all women (even if they were Athenian), and all foreigners or residents of foreign descent (no longer how long you and your family had lived in and worked in and contributed to the city and community).

It wasn’t foolproof considering it eventually got overthrown by power-seeking tyrants.

i.e. a part of ancient Greece had a democracy.

#classics#tagammemnon#classicsblr#rome#ancient rome#latin#ancient greece#classical greek#greece#[#classics: history#classics: language#|#did the romans and ancient greeks#google autocomplete#]

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

OCtober Day 2: Mercy

Thanks again to @oc-growth-and-development!

Ulla Teru is a siren with the power to conjure illusions to trick the five senses, but great power comes with a great price, and for Ulla this takes the form of headaches and hallucinations. She’s just recently taken over the siren kingdom and has made some interesting reforms as queen. She’s a charismatic leader, but a villain in the end, and well into an insanity arc that’s been pretty fun to write.

CW: emotional abuse, physical abuse (implied), hallucinations, fictional politics

Being a queen of a kingdom was a deceptively simple thing. It was being a queen of the people, Ulla had found, that was a challenge.

In an effort to convey her dedication to Kraseux to her citizens, one of her first measures enacted upon taking the throne was to hold open sessions for petitioners to come to the palace and air their grievances with the kingdom. The previous king had been absent frequently, and grossly out of touch with the people he dared call his, when in actuality, he had no clue what his subjects thought or demanded of him as a ruler.

Ulla would not rule like him. She would open her doors to her subjects, greet them from her throne with decorum and a charismatic smile as they knelt before her and poured out their hearts in hopes of some small mercy. And she would listen. She would promise nothing else, but she would listen, and often the illusion of a compassionate ear was enough, and they would go on their way feeling satisfied, approving of her methods and policy with unwavering loyalty. It was rather exhausting, but necessary.

The latest batch of petitioners were much like those from the day before, and every day before that: miserable, desperate, and forgettable. Each face blended into the next, an endless stream of flashing scales and tear-filled eyes as they begged for an extension on a loan payment, or an exemption from military service, or whatever else it was. Ulla listened attentively to each one, and had her attendants take note when it seemed appropriate. If she was feeling particularly generous, she might review the notes later that night before discarding them, but she wasn’t feeling generous often.

She called forward a Renegade who stood at the front of the line, noting the way he glanced back at the guards at the entrance to her throne room before kneeling. He looked as if he’d been turned shortly before becoming a grandfather, yet he wouldn’t meet her eyes. Ulla’s smile curled just a bit wider at that. She knew she looked young for a queen, even younger for a siren, but she commanded respect all the same. The illusion of maturity she wove over her true features only amplified it.

She let the silence hang in the air between them for a moment, then spoke in a soft tone, each word rippling with a smoothness like refined silk. “Rise, and state your business.”

The Renegade swallowed nervously, but drew himself up from his position. “Your Majesty, I’ve come to request compensation for an injury received while serving the kingdom. My superiors… they promised to file the request, but that was six months ago, and escalating the issue has done no good.”

Ulla raised a brow. “May I inquire as to the specifics of this… injury?” she questioned, leaning forward ever so slightly.

“The alignment in my tail is damaged,” he confessed, and indeed, Ulla could see where one fin lagged behind the other, even as he held himself in place. “I was hit by debris from the sinking of a human ship.”

A tense quiet persisted between them for a few moments, and Ulla tapped one finger against her chin in thought, flicking her own tail lazily. “Marianne,” she said, beckoning one of her attendants over, “please escort this gentleman to the proper offices in the military division to file his request and have it sent off.” The attendant hurried over and took the Renegade by the elbow, and Ulla’s demure smile briefly reappeared when he flinched. He was escorted away quickly, and she motioned for her scribe to record the details of their interaction before calling the next petitioner.

“Next.”

The black scales of a Deceptor came into view, and Ulla inclined her head ever so briefly as the woman knelt. She looked older than the Renegade before her, but no less respectful. The majority of Ulla’s own divining had been supportive of her reign since she was merely the Deceptor monarch, and they had reaped the rewards once she’d become queen. The days of Deceptors being reviled for their illusionary powers were soon coming to a close, and she was doing what she could to uplift their status as the superior divining of sirens. No longer would they be second-class citizens—not in Ulla’s Kraseux. “Rise,” she said.

“Your Majesty, I—I’ve noticed that more people in the capital are wearing Veritium jewelry,” the Deceptor woman began haltingly. Ulla sat up a little straighter, and conceded a small nod.

“Yes, I’ve noticed the same.” The cursed metal had fallen back into vogue when she’d assumed the role of queen, though Adonis had long since been a proponent of its illusion-breaking abilities. Not only did it stifle any Deceptor’s power who was too near to withstand it, it also bestowed adverse side effects that took any number of forms, depending on length and intensity of exposure. Ulla’s head began to ache just at the thought of it, even though her Deceptor guards strictly enforced her new policy forbidding the wearing of Veritium to these meetings.

The woman nodded vigorously. “I’ve heard tell that you plan on introducing legislation restricting the sale of Veritium in the capital. I came to request that you extend the boundary of that legislation to include the outskirts of the kingdom and the nearest colony as well. Some of my close friends find it hard to leave their homes without becoming ill. It’s harmful to our livelihoods. We can’t keep living like this, Your Majesty.”

“No,” Ulla mused, “you certainly can’t. Did you get that?” Her scribe paused to give her a short nod, then returned to writing frantically. Ulla smiled, watching the tension ease from the woman’s face as she received a tentative smile in return. “I’ll take that into consideration. You are dismissed.”

That woman’s obvious relief was quickly replaced as the next petitioner entered, an Auxilia man who appeared close to tears as he all but collapsed before her throne. Ulla’s smile vanished. “State your business.”

“Please, Your Majesty,” he begged, glancing fearfully at the guards, then back up to Ulla. He seemed quite intimidated. “The—the property taxes that you raised—I’ve been late on my rent for three months. If I can’t pay this time, I’ll get evicted—”

She held up one hand, and he fell silent. “Those taxes are necessary for repairing the infrastructure of our kingdom,” she said, exceedingly careful to keep her tone diplomatic and measured. “On the west end of the kingdom, correct? Your taxes have been raised to allow for maintenance of transportation currents in your area. Surely you knew this when you signed the contract for your lease?”

“I—I did, but… Your Majesty. It’s not just me. Other Auxilia in the area are struggling too, and—and Harmonia… we don’t need maintenance on transportation currents, we need to be able to live in our homes. I can’t make enough money to get by, there’s no jobs anywhere nearby because I don’t have the right qualifications. Please, Your Majesty—have mercy, or we’ll all be out on the streets, please have mercy…”

Ulla watched impassively as the Auxilia man worked in vain to conceal his desperation, his distress that was bringing him closer and closer to tears. Slowly, she lifted her gaze to meet the eyes of a guard, and inclined her head, motioning them over. To the man, she murmured, “Your concerns are not unwarranted, but rest assured, I and my fellow monarchs will find a solution for not just a few Auxilia, but the betterment of the entire kingdom. Now, if you would kindly compose yourself, I’ll have you escorted out.” She left no room for argument. It would do her public image no good for him to dissolve into a sobbing mess in her throne room.

Who was he to demand mercy from his queen?

~

She’d only heard a few more petitioners before closing requests for the afternoon, instructing her attendants to say that she had a great deal of work to attend to if anyone asked. They would assume that she’d taken many sirens’ requests to heart and was already beginning to process them, and she would allow them to think that for as long as they desired.

Ulla held no trust in her attendants. Only enough to know they would convey the message she told them to, nothing more, which was why she told no one the reason she’d retired to her rooms after the sessions was that a pounding headache was beginning to return. They were becoming easier to stave off now that Veritium was forbidden from most instances where it might come in close contact with her, but it was never completely avoidable. Adonis had always been paranoid, and some of the petitioners had worn scale implants that could not be removed for a short meeting. If her hallucinations were to arrive, Ulla wanted them to stay private.

The kingdom would never approve of a queen gone insane, no matter how much expertise she had taken in weaving her mask.

When Ulla reached her chambers, she locked the door behind her so no attendants could trail in her wake, then removed the crown that had sat upon her head and set it aside. There were no mirrors in her rooms, as there never had been. Her illusions could trick a mirror, but if the hallucinations so commanded it, the illusions could fall just as easily.

She drifted over to a window and clasped her hands behind her back. The Auxilia man was not yet out of sight, swimming far slower than the sirens around him due to his lack of a true tail. After a moment, she turned away from the window, but she could still hear his voice in the back of her mind, growing louder and more desperate until it filled the room.

“Please, have mercy… have mercy, or we’ll all be out on the streets… please have mercy…”

At some point, his voice had become her own. She wasn’t sure when.

Her father stood over her, the room distorted and rippling around them. Mercy, Ulla? he murmured, saccharine and dangerous, and she shrank away. Her tail was made of lead with the iridescent glint of Veritium, and it pulled her to the ground.

“No, please… I didn’t mean to, Father,” she whispered as her leaden tail gave way to leaden legs, short and spindly and unable to support the weight of her pleas. “I don’t—I don’t know what I did…”

Why, you’ve killed that man, the hallucination said with a wicked, sharp-toothed grin, and Ulla shook her head violently.

“I didn’t, it’s not my fault!”

Oh, but it is, her father said. You’ve killed that man as sure as you’ve killed your own mother. She’d be disgusted if she saw you like this—but she can’t, because she’s not alive to see it. The hallucination stepped closer, and Ulla shrank away again. It was no use crying for her mother—she never came when her father did. She’d died minutes after Ulla was born. Ulla’s mind could only conjure the dead she had known, because to be known was to never truly die.

Do you really wish to test me, Ulla? You look like your mother did at that age, you know. It would be a shame if you were to force me to change that.

“No, please,” she begged, loathing every word that fell from her tongue and yet being powerless to stop them. “Have mercy, please have mercy…”

The hallucination raised its ghostly hand, and the fingers elongated into jagged talons. Shadows around the edge of the room pressed in closer, piling heavy onto her chest and wrapping around her legs and arms and mouth. Her father brought his talons down. Ulla closed her eyes and screamed.

~

When Ulla opened her eyes, she was the only one in the room. The side of her face stung, but when she raised a shaking finger to probe for injury, nothing was there. A stream of bubbles rose up towards the ceiling, but no figures stood looming over her where she lay crumpled on her side on the floor.

Slowly, she sat up. The pain was an illusion, and it would go away when she regained control. She’d lost control for far too long that time. Her hallucinogenic episodes were lasting longer and becoming more frequent, but nobody had witnessed it. No one had been around when she’d lost control of her mind and her powers, and it would stay that way.

The streetlamps outside her window were beginning to glow, betraying the time that had passed. They’d be expecting her for a state dinner soon. Carefully, Ulla began to weave her illusions over her face once more, and only when the painstaking process was finished did she allow herself to breathe.

No one knew what happened when Ulla’s illusions fell.

A queen did not beg for mercy.

No one would ever know.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

América Invicta

The Capaq Inka still rules the Four Regions. The great temples still cast their shadow over Lake Texoco. About three centuries ago, conquerors from overseas tried, and failed, to impose their rule over these lands.

It is the year 1800 -or so- on the Christian calendar. Much has happened since then.

Tawantinsuyu, the great empire of the Andes, lays claim to the whole of Septentrional America. Its wealth and power unmatched, millions of people of all creeds and nations live on its golden cities. The great city of Qusqu, the Navel Of The World, is the center of culture and trade for the entire continent, its surrounding terraces grow food from all over the empire. Warriors clad in golden armor bearing muskets ride Megatheriums to the farthest reaches of the empire to enforce the will of the Capaq Inka.

Yet the many peoples of the Americas do not bow easily. For the trading cities of the living jungle of the Paranaguazú, the Muisca kingdoms from the highlands of the north, the Carib towns on the warm shores of the Atlantic Ocean, the thousand tribes of the dry forests of Chaqu, the horse riders of windy Patagonia, the Gauchos of the Pampas, the rebellious former colonies of Buen Ayre, Nueva Granada and Recife, the monasteries of the Jesuits, the free Quilombos of former slaves, the mysterious kingdoms of Xingú and the defiant Tamoio Confederation, the rule of the Inka is more of a formality than anything concrete. Roads and tambos made by the great Inkanate connect millions and are full of merchants, explorers, soldiers, wizards, priests and adventurers at the service of many powers (or none), trying to make their fortune in this land.

They are not the only ones on this continent. Up North, the Obsidian Alliance, the successors of the fallen Triple Alliance of the Mexica, try to keep together the disparate city-states of Mesoamerica. The Mayan principalities expand into the volcanic rainforests of the south. The paradisiacal Caribbean Sea is a place of intrigue for Taíno war canoes, European galleons, and African caravels who compete for the rich trade routes. ‘Pirates’ free slaves and raid plantations on the coasts, and their sons and daughters make new lives in freedom. Refugees from the European Wars of Religion inmigrate to the New World to find a place to begin anew. Gauchos and Llaneros herd the giant herds of cattle in the plains, and face off against bizarre spirits and creatures. Grand Treasure Ships from the East (or is it West?) come to the seaports to trade with the rich empires. Jesuit priests roam the imperial roads, preaching the word of Christ and teaching the sciences. Muslim traders call to prayer from miranets rising above the tropical shores. Up the Missisippi grow the cities of the Mound Builders and beyond the heartland of the Obsidian Alliance the dry deserts bloom with powerful civilizations. Uncanny wandering sorcerers travel through the land, full of wisdom and powers so strong that many serve the empires of the continent; others are comfortable tending to the needs of the common people or enhancing their knowledge.

And much remains unknown. Herds of giant animals, supposedly long-extinct, roam the plains of the continent and sleep under its hidden swamps; armored mammals, giant reptiles, elephants completely unlike those in Africa or Asia, majestic feathered serpents… The forests are alive with a thousand spirits, who resist the attempts of greedy men to tame them. The winds seem to talk with their own voice, and old men and women claim to speak for the land itself. Giant sea ‘monsters’ roam the cold seas of the South. Christians testify of great miracles, and many saints, recognized or not, are venerated all over the land. Many tribes, maybe even entire civilizations, are still unknown, hidden by mountains, jungle, or uncanny fog. Explorers hear legends about animal-people and powerful sorcerers, and there is reason to believe them. Sunk treasure galleons are sought by pirates and adventurers. Mysterious books and relics are lost in libraries and palaces.

And in the great cities of the continent, from Qusqu to Tenochtitlán, Maracaibo to Palmares, Quito to Rio de Janeiro, Recife to Buen Ayre, smoky chimneys and glass buildings rise over the old temples and cabildos, powered by strange machines operating by a stranger combination of magic and science, heralding the start of a new era.

It is, indeed, a New World.

...

The mighty Paraná River slowly made way besides the little port town of Corrientes. Winter was ending; the muddy, narriw streets were decorated by a thousand flowers falling from the lapacho trees, every little breeze tinted by pink, yellow and white.

The first sunday of spring slowly winded down.

In the cabildo, the governor of the Argentine Confederation and the curaca of the Four Regions loudly debated about tribute and power and who had most of it, like they always did. The bells of the churches announced the evening service. Fishermen brought the fruits of a long afternoon in the waters shadowed by the riparian forests. The patrol cutters of the Confederation sailed into the port. The stalls on the central plaza were closing down, farmhands heading with their cattle back home to the fields.

In a tiny pulpería above the river cliffs -not very tall, but still giving a nice view of the sleeping sun above the forests on the other side of the river- the Witch and the Gaucho fought back the early heat of spring with a cold beer.

"...So, " the Witch continued explaining, excitedly, "the book says there's this point, somewhere. The beginning of it all. Or maybe the end. Most probably both, or perhaps all what it's in between."

"Uh huh. I see." Answered the Gaucho. Despite his tone of voice, he was geniunely interested. If a little confused.

"And we could see through it. It, somehow, reflects all the universe. Maybe more." Just to even think about other universes, dreamed the Witch! "But it's very confusing to look at it. It's too much for us to percieve. Because I mean, surely you can hear and smell and feel too. But you can't process it. It's like, like..."

"Like looking through a glass marble near your eye, with all those strange scratches and... things. Only it's the entire universe." Affirmed the Gaucho, drinking another sip from the beer.

He wasn't sure if the alcohol made him a better philosopher or it just made him remember his childhood days playing with marbles.

"YES! That's right! You get me! I KNEW buying you a beer was worth it."

"It was worth for me, at least..." He smiled. She smiled back.

"Now, when you see through a marble," she continued "you see all that weird stuff because your eyes only can see through a single... size so to speak."

A horn blared.

Parrots flew away from the palm trees. The very wind seemed to stop still.

The Witch, though, continued.

"...but imagine if we could see with different eyes. If we could..."

"Che... What the hell is that noise?"

They looked at the great Paraná, which was suddenly covered by foamy waves.

It was a boat.

It wasn't, though, one of the Guaraní fishing canoes that always sailed up and down the Paraná. Neither it was one of the proud sailboats of the Confederation, or the golden arks of the Capaq Inka.

It was a huge metal monolith, like some kind of iron bathtub uncannily floating in the water. Two chimneys vomited black smoke into the golden skies, and chains of... magical? light illuminated the ship. Shipmen dressed in white marched through the deck as the vessel made way through the river, with no sails, with no oars, with no magic, apparently propelled by hubris itself.

And while neither the Witch or the Gaucho were very familiar with ships, they could certainly see that those big metal boxes with cannons pointing from them were inmensely powerful weapons.

In the back, in golden, exquisitely craved letters, the name of the vessel read:

'HMS Dreadnought'

#cosas mias#américa invicta#fantasy#worldbuilding#latin america#long post#wow a plot? who would've thought

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Role of Women In Traditional African Societies

One area where the traditional societies were well advanced than their Western counterparts was in the area of women’s rights. Women in non-Western traditional societies were long “liberated” before those in the West. In fact, the Western feminist movement drew a lot of inspiration from the role women played in traditional Iroquois society. According to Jacobsen (2009),

An aspect of Native American life that alternately intrigued, perplexed, and sometimes alarmed European and European-American observers, most of whom were male, during the 17th and 18th centuries, was the influential role of women. In many cases they hold pivotal positions in Native political systems. Iroquois women, for example, nominate men to positions of leadership and can “dehorn,” or impeach, them for misconduct. Women often have veto power over men’s plans for war. In a matrilineal society — and nearly all the confederacies that bordered the colonies were matrilineal — women owned all household goods except the men’s clothes, weapons, and hunting implements. They also were the primary conduits of culture from generation to generation.

The role of women in Iroquois society inspired some of the most influential advocates of modern feminism in the United States. The Iroquois example figures importantly in a seminal book in what Sally R. Wagner calls “the first wave of feminism,” Matilda Joslyn Gage’s Woman, Church, and State (1893). In that book, Gage acknowledges, according to Wagner’s research, that “the modern world [is] indebted [to the Iroquois] for its first conception of inherent rights, natural equality of condition, and the establishment of a civilized government upon this basis.”

Gage was one of the 19th century’s three most influential American feminists, with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Gage herself was admitted to the Iroquois Council of Matrons and was adopted into the Wolf Clan, with the name Karonienhawi, “she who holds [up] the sky.” (Jacobsen, 2009).

It is not just in the Iroquois nation that women held important political positions. As we have shown above, most traditional societies have Clan or Queen Mothers with the power to appoint and depose a chief. Her role is to scold, reprimand and rebuke an erring chief since a bad chief brings shame to the royal family. If the chief continues in his errant ways, the Queen Mother has the power to recall and depose the chief.

In other traditional; systems, women even played a more visible political role:

· Women ruled the Mongol Empire (Weatherford, 2005).

· Quen Nzinga of the Mbundu people of Angola put up a ferocious resistance against Portuguese colonial rule (http://www.blackpast.org/?q=gah/queen-nzinga-1583-1663).

· The kings of Dahomey were assisted by a cabinet which consisted of the migan (prime minister); the meu (finance minister) created by Tegbesu; yovo-gan (viceroy of Whydah); the to-no-num (the chief eunuch and minister in charge of protocol); the tokpo (minister of agriculture); the agan (general of the army); and the adjaho (minister of the king's palace and the chief of police). The most interesting and unique feature of the cabinet was that each of these posts had a female counterpart who complemented him but reported independently to the king (Ayittey, 2006: 243).

· During his reign, Gezo increased the number of the full-time soldiers from about 5,000 in 1840 to 12,000 by 1845. This army consisted not only of men but also of women, the famous Amazons `devoted to the person of the king and valorous in war.' This unique female section was created and organized by Gezo and consisted of 2,500 female soldiers divided into three brigades. Commanders of this army were also top cabinet ministers in charge of the central government thus enhancing the position of the army in decision making (Boahen, 1986; p.86).

· In the Yoruba Kingdom (Nigeria) in early times it was not necessarily a male who was chosen as ruler, and the traditions of Oyo, Sabe, Ondo, and Ilesa record the reigns of female oba (kings) (Smith, 1969: 13).

· In Asante, the British captured and exiled the king to Sierra Leone in January 1897. But to the Asante, it was the golden stool, not the king, was the symbol and soul of their nation. When the British made a vain attempt to capture the golden stool in April 1900, they met a stiff and humiliating defeat at the hands of an Asante woman, Yaa Asantewa, the Queen Mother of Edweso. Though this rebellion was finally crushed, the British never gained possession of the golden stool. Of course, British historians rarely mention this defeat, much less at the hands of a woman!

Needless to say, there were bad women rulers too. One was Dode Akabi, whose accession to power constituted the first major female figure in Gá, and indeed Gold Coast. But in her long reign, 1610-1635, she cast aside the practice of rule by consensus and issued a series of brutal decrees which displeased her people. She was f killed after she had ordered her subjects to sink a well at a place called Akabikenke (Ayittey, 2006: 232)

Women In The Traditional Economic System

With the exception of Islamic countries in the Middle East, women also played a much more visible and important role in the traditional economy – especially in agriculture and market trading. Most traditional societies practice sexual division of labor. In early times, activities considered dangerous and physically strenuous such as waging wars, hunting, fishing, manufacturing (cloth weaving, pottery, leatherworks, iron smelting, sculpturing, etc) and building were male occupations. Food cultivation and processing were traditionally reserved for women. Since the family's entire needs could not be produced on the farm, a surplus was necessary to exchange for those items. It was only natural that trade in foodstuffs and vending came to be handled by women and for market governance to lie in their hands. Indeed in many localities, market rules were generally laid down and enforced by "Market Queens", usually selected from the women traders.

Women still play this role today since agriculture continues to account for a higher share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of developing countries. For example, three out of four Africans are engaged in agriculture, with women making the most significant contribution. They perform “some 90 percent of the work of food processing, 80 percent of food storage tasks, 90 percent of hoeing and weeding, and 60 percent of harvesting and marketing, besides load carrying and transport services” (FAO, 1985, Chapter 7).[i] Rural markets and trade are also largely handled by women. Local farm produce ‑ either cash crops or food crops ‑ are marketed at the local market, almost invariably by women.

In West Africa, for example, market activity has been dominated by women for centuries:

· In 1879, Governor Rowe of Sierra Leone expressed his admiration of these women: “The genius of the Sierra Leone people is commercial; from babyhood the Aku girl is a trader, and as she grows up she carries her small wares wherever she can go with safety. The further she goes from the European trading depots the better is her market” (White, 1987; p.27).

· The market in every Ga town is run entirely by women. No trading, except that initiated by foreigners is ever carried on by men...Many of the women are very shrewd and ingenious in their trading. One day when good catches of fish were coming in I saw a woman, who had no fishing men‑folk, exchange a bowlful of fried akpiti cakes for a panful of fresh fish, and then hastily sell the fish to a `stranger' who was trying to make up a load to take away. The sale of the fish brought her three shillings and four pence. The sale of the cakes would have brought her one and sixpence. The materials out of which she made the cakes probably cost less than sixpence (Field, 1940: 64).

· The market place among the Akan of Ghana is largely a woman's world. Except for the small percentage of traders who are men, the processes of trade are said to be mysteries to men. Men often seem uncomfortable in the market; they prefer to send a woman or a child to make purchases for them, and avoid entering it if possible. For women, the market place is not only a place of business but of leisure as well. Sales are sometimes slow and women chat and josh with each other” (McCall, 1962).

· In South Dahomey, commercial gains are a woman's own property and she spends her money free of all control...Trade gives to women a partial economic independence and if their business is profitable they might even be able to lend some money ‑ a few thousand francs ‑ to their husbands against their future crops (Tardits and Tardits, 1962).

The object in trading was to make a profit. The Yoruba women "trade for profit, bargaining with both the producer and the consumer in order to obtain as large a margin of profit as possible" (Bascom, 1984; p.26). And profits made from trading were kept by the women in almost all of the West African countries.

Though the amount of profit was often small by today’s standards, many women traders were able to accumulate enough for a variety of purposes: to reinvest and expand their trading activities, to cover domestic and personal expenses since spouses have to keep the house in good condition, to replace old cooking utensils, to buy their own clothes and to educate their children. The case of Abi Jones was earlier cited where profits from her trading were used to educate her sons. Indeed, many of the post‑colonial leaders of Africa were similarly educated ‑ with funds accumulated from trading profits.

Another important use of trade profits was the financing of political activity. As Herskovits and Harwitz (1964) put it: "Support for the nationalist movements that were the instruments of political independence came in considerable measure from the donations of the market women" (p.7).

To start trading, women often looked to their husbands for support or borrowed from the extended family pot. For example,

As soon as he is married the Ga husband is expected to set his wife up in trade (`ewo le dzra' ‑ he puts her in the market). It is part of every woman's normal occupation to engage in some sort of trade and every reasonable husband is expected to start her off...When she is unlucky in her trading and loses her capital her husband is expected to set her up again, but if she loses her capital three times she is a bad manager and he has no further obligation in the matter (Field, 1940:55).

Market trading generally made African women economically independent. Chatting at the market place also provided an important social release for pent‑up emotions. Of course, today, much of this market activity has spilled over into the informal sector, where women still play an important role in food-related activities, such as, food vending by the roadside.

[i] Perhaps this gender characteristic explains why Africa’s agriculture revolution never materialized. In many countries, it was crafted with the help of Western agricultural experts who tended to prescribe “mechanization” with the importation of male-driven agricultural machinery.

References Ayittey, George B.N. (2006) Indigenous African Institutions. Dobbs Ferry, NY: Transnational Publishers.

Bascom, William (1984). The Yoruba Of Southwestern Nigeria. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press, Inc.

Boahen, A.A. (1986). Topics in West African History. New York: Longman.

Bohannan, Paul and George Dalton eds. (1962). Markets In Africa. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Field, M. J. (1940). Social Organization of the Ga People. Accra: Government of the Gold Coast Printing

Herskovits, M.J. and Harwitz, M. eds. (1964). Economic Transition In Africa. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Jacobsen, E. (2009) The Iroquois Constitutionhttps://ca01001129.schoolwires.net/cms/lib7/ca01001129/centricity/domain/221/the_iroquois_constitution.pdf

Johansen, Bruce E. (1990). “Native American Societies and the Evolution of Democracy in

America, 1600-1800,” Ethnohistory, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Summer, 1990): pp. 279-290.

______________ “Native American Ideas of Governance and U.S. Constitution

http://www.america.gov/st/peopleplace-english/2009/June/20090617110824wrybakcuh0.5986096.html

McCall, Daniel F. (1962). "The Koforidua Market," in Bohannan and Dalton, eds. (1962).

Smith, Robert S. (1969). Kingdoms of The Yoruba. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd

Tardits Claudine and Claude (1962). "Traditional Market Economy in South Dahomey" in Bohannan and Dalton (1962).

Weatherford, Jack (1989). Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas transformed the World. New York: Ballantine, 1989.

_______"The Women Who Ruled the Mongol Empire", Globalist Document - Global History, June 20, 2005

White, E. Frances (1987). Sierra Leone's Settler Women Traders. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Can you believe ...?

Perhaps no question has been repeated more times in reaction to more events this year than that one.

The most recent major outrage in the Jewish community, now several news cycles behind us, came on the Shabbat before Yom Kippur—the holiest day in the Jewish calendar—when many American Jews seemed dumbfounded by what was to me predictable news: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, progressive superstar, had pulled out of an event honoring Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli prime minister assassinated because of his efforts to make peace with the Palestinians. Rabin was, as Bill Clinton said at his funeral, “a martyr for his nation’s peace.”

…

But it wasn’t AOC who was mixed up. The savvy politician had read the room and was sending a clear signal about who belongs in the new progressive coalition and who does not. The confusion—and there seems to be a good deal of it these days—is among American Jews who think that by submitting to ever-changing loyalty tests they can somehow maintain the old status quo and their place inside of it.

Did you see that the Ethical Culture Fieldston School hosted a speaker that equated Israelis with Nazis? Did you know that Brearley is now asking families to write a statement demonstrating their commitment to “anti-racism”? Did you see that Chelsea Handler tweeted a clip of Louis Farrakhan? Did you see that protesters tagged a synagogue in Kenosha with “Free Palestine” graffiti? Did you hear about the march in D.C. where they chanted ��Israel, we know you, you murder children too”? Did you hear that the Biden campaign apologized to Linda Sarsour after initially disavowing her? Did you see that Twitter suspended Bret Weinstein’s civic organization but still allows the Iranian ayatollah to openly promote genocide of the Jewish people? Did you see that Mayor Bill de Blasio scapegoated “the Jewish community” for the spread of COVID in New York, while defending mass protests on the grounds that this is a “historic moment of change”?

Listen, it’s been a hell of a year. We all have a lot going on, much of it unnerving and some of it dire. Moreover, many of these stories only surface on places like Twitter; they don’t make it into the pages of The New York Times or your friends’ Facebook feeds, which is where most Americans get their news these days. Reporters don’t cover these stories adequately, contextualizing them, telling readers which ones are true and which ones aren’t, which ones matter and which ones don't.

So it makes sense that many smart, well-intentioned people are confused. Or rather: Looking for someone to explain why an emerging movement that purports to advance the ideals they have always supported—fairness, justice, righting historical wrongs—feels like it is doing the opposite.

…

To understand the enormity of the change we are now living through, take a moment to understand America as the overwhelming majority of its Jews believed it was—and perhaps as we always assumed it would be.

It was liberal.

Not liberal in the narrow, partisan sense, but liberal in the most capacious and distinctly American sense of that word: the belief that everyone is equal because everyone is created in the image of God. The belief in the sacredness of the individual over the group or the tribe. The belief that the rule of law—and equality under that law—is the foundation of a free society. The belief that due process and the presumption of innocence are good and that mob violence is bad. The belief that pluralism is a source of our strength; that tolerance is a reason for pride; and that liberty of thought, faith, and speech are the bedrocks of democracy.

The liberal worldview was one that recognized that there were things—indeed, the most important things—in life that were located outside of the realm of politics: friendships, art, music, family, love. This was a world in which Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg could be close friends. Because, as Scalia once said, some things are more important than votes.

Crucially, this liberalism relied on the view that the Enlightenment tools of reason and the scientific method might have been designed by dead white guys, but they belonged to everyone, and they were the best tools for human progress that have ever been devised.

Racism was evil because it contradicted the foundations of this worldview, since it judged people not based on the content of their character, but on the color of their skin. And while America’s founders were guilty of undeniable hypocrisy, their own moral failings did not invalidate their transformational project. The founding documents were not evil to the core but “magnificent,” as Martin Luther King Jr. put it, because they were “a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.” In other words: The founders themselves planted the seeds of slavery’s destruction. And our second founding fathers—abolitionists like Frederick Douglass—made it so. America would never be perfect, but we could always strive toward building a more perfect union.

I didn’t even know that this worldview had a name because it was baked into everything I came into contact with—my parents’ worldviews, the schools they sent me to, the synagogues we attended, the magazines and newspapers we read, and so on.

…

No longer. American liberalism is under siege. There is a new ideology vying to replace it.

No one has yet decided on the name for the force that has come to unseat liberalism. Some say it’s “Social Justice.” The author Rod Dreher has called it “therapeutic totalitarianism.” The writer Wesley Yang refers to it as “the successor ideology”—as in, the successor to liberalism.

…

The new creed’s premise goes something like this: We are in a war in which the forces of justice and progress are arrayed against the forces of backwardness and oppression. And in a war, the normal rules of the game—due process; political compromise; the presumption of innocence; free speech; even reason itself—must be suspended. Indeed, those rules themselves were corrupt to begin with—designed, as they were, by dead white males in order to uphold their own power.

…

Critical race theory says there is no such thing as neutrality, not even in the law, which is why the very notion of colorblindness—the Kingian dream of judging people not based on the color of their skin but by the content of their character—must itself be deemed racist. Racism is no longer about individual discrimination. It is about systems that allow for disparate outcomes among racial groups. If everyone doesn’t finish the race at the same time, then the course must have been flawed and should be dismantled.

…

In fact, any feature of human existence that creates disparity of outcomes must be eradicated: The nuclear family, politeness, even rationality itself can be defined as inherently racist or evidence of white supremacy, as a Smithsonian institution suggested this summer. The KIPP charter schools recently eliminated the phrase “work hard” from its famous motto “Work Hard. Be Nice.” because the idea of working hard “supports the illusion of meritocracy.” Denise Young Smith, one of the first Black people to reach Apple’s executive team, left her job in the wake of asserting that skin color wasn’t the only legitimate marker of diversity—the victim of a “diversity culture” that, as the writer Zaid Jilani has noted, is spreading “across the entire corporate world and is enforced by a highly educated activist class.”

The most powerful exponent of this worldview is Ibram X. Kendi. His book “How to Be an Antiracist” is on the top of every bestseller list; his photograph graces GQ; he is on Time’s most influential people of the year; and his outfit at Boston University was recently awarded $10 million from Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey.

…

And just in case moral suasion is ineffective, Kendi has backup: Use the power of the federal government to make it so. “To fix the original sin of racism,” he wrote in Politico, “Americans should pass an anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution that enshrines two guiding anti-racist principals [sic]: Racial inequity is evidence of racist policy and the different racial groups are equals.” To back up the amendment, he proposes a Department of Anti-Racism. This department would have the power to investigate not just local governments but private businesses and would punish those “who do not voluntarily change their racist policy and ideas.” Imagine how such a department would view a Jewish day school, which suggests that the Jews are God’s chosen people, let alone one that teaches Zionism.

Kendi—who, it should be noted, now holds Elie Wiesel’s old chair at Boston University—believes that “to be antiracist is to see all cultures in their differences as on the same level, as equals.” He writes: “When we see cultural difference we are seeing cultural difference—nothing more, nothing less.” It’s hard to imagine that anyone could believe that cultures that condone honor killings of unchaste young women are “nothing more, nothing less” than culturally different from our own. But whether he believes it or not, it’s obvious that embracing such relativism is a highly effective tool for ascension and seizing power.

It should go without saying that, for Jews, an ideology that contends that there are no meaningful differences between cultures is not simply ridiculous—we have an obviously distinct history, tradition and religion that has been the source of both enormous tragedy as well as boundless gifts—but is also, as history has shown, lethal.

By simply existing as ourselves, Jews undermine the vision of a world without difference. And so the things about us that make us different must be demonized, so that they can be erased or destroyed: Zionism is refashioned as colonialism; government officials justify the murder of innocent Jews in Jersey City; Jewish businesses can be looted because Jews “are the face of capital.” Jews are flattened into “white people,” our living history obliterated, so that someone with a straight face can suggest that the Holocaust was merely “white on white crime.”

This is no longer a fringe view. As the philosopher Peter Boghossian has noted: “This ideology is the dominant moral orthodoxy in our universities, and has seeped out and spread to every facet of American life— publishing houses, tech, arts, theater, newspapers, media,” and, increasingly, corporations. It has not grabbed power by dictates from above, but by seizing the means of sense-making from below.

Over the past few decades and with increasing velocity over the last several years, a determined young cohort has captured nearly all of the institutions that produce American cultural and intellectual life. Rather than the institutions shaping them, they have reshaped the institutions. You don’t need the majority inside an institution to espouse these views. You only need them to remain silent, cowed by a fearless and zealous minority who can smear them as racists if they dare disagree.

It is why California attempted to pass an ethnic studies curriculum whose only mention of Jews was to explain how they, along with Irish immigrants, were invited into whiteness.

It is why those who claim to care about diversity and inclusion don’t seem to care about the deep-seated racism against Asian Americans at schools like Harvard.

It is why a young Jewish woman named Rose Ritch was recently run out of the USC student government. Ms. Ritch stood accused of complicity in racism because, following the Soviet lie, to be a Zionist is to be nothing less than a racist. Her fellow students waged a campaign to hound her out of her position: “Impeach her Zionist ass,” they insisted.

It is why the Democratic Socialists of America, the emerging power center of the Democratic Party in New York, sent a questionnaire to New York City Council candidates that included a pledge not to travel to Israel.

It is why Tamika Mallory, an outspoken fan of Louis Farrakhan, gets the glamour treatment in a photoshoot for Vogue.

And this is why AOC, the standard bearer of America’s new left, didn’t think Yitzhak Rabin was worth the political capital, but goes out of her way, a few days later, to praise the Black Panthers. She is the harbinger of a political reality in which Jews will have little power.

It does not matter how progressive you are, how vegan or how gay, how much you want universal health care and pre-K and to end the drug war. To believe in the justness of the existence of the Jewish state—to believe in Jewish particularism at all—is to make yourself an enemy of this movement.

…

If you’re nearing the end of the essay wondering why this hasn’t been explained to you before, the answer is because, yet again, we find ourselves in another moment in Jewish history at a time of great need and urgency with communal leadership who, with rare exception, will not address the danger.

I understand why people have been blind to this. Life has been good—exceedingly good—for American Jews for half a century. Many older communal leaders seem to lack the moral imagination to see this threat. It’s also hard for anyone to hear the words: They’re just not that into you.

So when I try to discuss this with many Jews in leadership positions, what I face is either boomer-esque entitlement—a sense that the way the world worked for them must be the way it will always work—or outright resistance. Oh please, wokeness isn’t important anywhere but in silly Twitter microclimates. When you explain that no, in fact, this ideology has taken over universities, publishing houses, the media, museums and is now making quick work of corporate America, you hit another roadblock: Isn’t this just righting some historical injustices? What could go wrong? You then have to explain what could go wrong—what is already going wrong—is that it is ruining the lives of regular, good people, and the more institutions and companies fall prey to it, the more lives it will ruin.

…

Last month, I participated in a Zoom event attended by several major Jewish philanthropists. After briefly talking about my experience at The New York Times, I noted that if they wanted to understand what happened to me, they needed to appreciate the power of that new, still-nameless creed that has hijacked the paper and so many other institutions essential to American life. I’ve been thinking about what happened next ever since.

One of the funders on the call launched into me, explaining that Ibram X. Kendi’s work was vital, and portrayed me as retrograde and uncool for opposing the ideology du jour. Because this person is prominent and powerful enough to send signals that others in the Jewish world follow, the comments managed to both sideline me and stun almost everyone else into silence.

These people may be the most enraging: those with the financial security to oppose this ideology and demur, so desperate to be seen as hip; for their children to keep their spots at the right prep schools; so that they can be seated at the right tables at the right benefits; so that they are honored at Brown or Harvard; so that business does well enough that they can renovate their house in Aspen or East Hampton. Desperate to remain in good odor with the right people, they are willing to close their eyes to what is coming for the rest of us.

Young Jews who grasp the scope of this problem and want to fight it thus find themselves up against two fronts: their ideological enemies and their own communal leadership. But it is among this group—people with no social or political capital to hoard, some of them not even out of college—that I find our community’s seers. The dynamic reminds me of the one Theodor Herzl faced: The communal establishment of his time was deeply opposed to his Zionist project. It was the poorer, younger Jews—especially those from Russia—who first saw the necessity of Zionism’s lifesaving vision.