#but i tried to address it from an in-universe characterization point of view i guess

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

So, I know your interests in the show are more focused elsewhere, but you've seen Boardwalk Empire a lot (I assume), so maybe you'll have a good answer. Why did it seem like Nucky and Margaret were so immediately interested in each other? Like, what about the other was alluring? I never got that. They always seemed like an odd pair to me.

honestly i think i’m too queer to give a satisfying answer to this but i will try uhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh well so i think on nucky’s end margaret is sort of… she’s an interesting mix of qualities i don’t think he’s ever really encountered in a woman he’s been interested in since mabel’s death? because she is in dire straits at the start of s1, she needs to be saved, and that’s Nucky’s Thing, he enjoys playing the benefactor and the feeling of superiority [moral or monetary] he gets out of helping people less ruthless fortunate than him, especially women. at the same time, she’s whip fucking smart and a challenge in a way girls like lucy and even billie later aren’t; billie challenges nucky in terms of her independence and how he treats her as an individual, but margaret holds moral and political positions that are very contrary to some of nucky’s, and she’s not afraid to express them whether he likes it or not. the look he gives her when he sees her outside the celtic dinner is respect, not disdain, and [no shade intended on lucy here] he absolutely does not respect lucy, or any of the other women he has flings with. so i think a lot of nucky’s attraction to margaret is the desire to save her, the drastic difference in her intelligence and wit to the women we see nucky with/implied to have been with prior to margaret*, and the way those two mental images he has of her clash probably go a long way to explaining why he’s so interested in her, to say nothing of the fact that she’s gorgeous.

* he does respect sally, but i think it’s in the same way he respects margaret’s willingness to stick up for what she believes in, with the difference in beliefs being “i believe in the worth of all women and demand what’s best for my family” vs “i believe i can run rum and do business as good as any of you dicksucks”

figuring out margaret’s interest is a little harder for me because… she is a goddess and nucky is a jerkwad. but we’re all also sitting here having watched all five seasons, and we know exactly how he’s going to treat her down the line. in season one, all margaret knows is she’s just gotten out of a physically abusive relationship, and now a man she respects and who has enough money to not only keep her safe, but to afford her children opportunities they’d never get otherwise, is interested in a relationship with her. in early s1 nucky to margaret is respectful, well-mannered, and treats her kids very paternally, which is ultimately a thing she values the most about her relationship with him. plus like… it really can’t be overstated that she just got out of a relationship with a man who beat her so hard she miscarried. abuse recovery is not fast and it is not linear and it does not always mean you immediately realize that someone treating you better than the person who treated you the worst may still not be treating you as well as you deserve, and when that ‘less shitty but still shitty’ person is the closest person you have IMMEDIATELY after getting out of a really bad situation, margaret is probably downplaying anything that sets off any alarm bells for her in nucky’s behavior [at least until he gets violent]. so for her i think it’s sort of a mix of a rational calculus of “he has money, he can provide for my children and for me, and if it does turn sour he probably will not do anything as bad as what i’ve already survived from hans” and the more emotional component of “he saved me from hans and he genuinely seems to want to be a father to my children” that has her interested? those are my guesses at least. hopefully that makes some sort of sense?

#boardwalk empire#nucky thompson#margaret rohan#I'M REALLY TOO QUEER TO UNDERSTAND HETEROSEXUAL PLOTLINES WRITTEN BY HETEROSEXUAL MEN#i mean a ton of it is obviously also wish fulfillment stuff on the writers' parts#but i tried to address it from an in-universe characterization point of view i guess#Anonymous#asks

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want to address the “boba fett is catholic” meme i’m seeing in the notes of my post, bc, while hilarious, it’s actually quite an interesting bit of expanded universe history!

from what i understand, the meme comes from someone quoting a snippet from the expanded universe in which boba fett says that he considers sex outside of marriage immoral. which, yeah, is a weirdly catholic thing for him to say. so let me provide some context.

this quote is taken from the short story “the last one standing” by daniel keys moran. daniel keys moran wrote probably some of the strangest prose about fett and was the first writer to really take a crack at his backstory (this was well before aotc when boba was revealed to be a clone), as well as his history with han solo. if you like, uh, smoother characterizations of boba fett, you might not like this version so much: some words to describe moran’s boba fett would be obsessive, paranoid, and disturbed.

anyway, most of moran’s writing (aside from a few snippets that were expanded on but we’ll get to that later) was retconned after aotc, so if you just want to be like, “nope, boba fett never said that shit, never happened,” while still exploring other legends material, then absolutely feel free. but if you want several textually-supported reasons for why he’d say something like that that aren’t being space catholic, read on.

so, first of all, the immediate context: why tf is a bounty hunter talking about extramarital sex at all? well, the context is that boba fett is in jabba’s palace after leia has been captured. she has been sent to his room as a reward (ugh) and he’s trying to persuade her that 1. he doesn’t intend to assault her and 2. she really should just crash in his room for the night anyway bc if she goes back to jabba, it’ll be seen as a sign of disrespect and they’ll both get in trouble. leia is understandably on-edge and mistrusting of him and this is when he says the “sex between those not married is immoral” thing; he’s trying to convince leia that he really isn’t going to touch her.

(for those wondering, he doesn’t. he gives her some blankets to cover herself and lets her sleep in the bed while he spends the night sitting on the floor)

so! if you so wish, you could easily explain the whole thing as boba saying space catholic shit (whether he actually believes it or not) to reassure leia that she’s safe in his room for the night. he says himself that if she were to go back to jabba, jabba would likely take boba’s refusal to touch her as an insult and take retribution against him, so boba has plenty of incentive to try and convince leia to do otherwise.

but wait! what if you’re fine with boba having hang-ups about sex and relationships and just want a reason other than just “space catholicism?” well, friends, the good news is that that reading is even more supported by the text in a way that would later be expanded upon in post-aotc legends content.

though, before we proceed, lemme just slap down a content warning for discussion of drugs, sexual assault, and the intersection thereof.

now, back to “the last one standing.” leia eventually decides to trust fett and the two proceed to have a really awkward slumber party. leia, noting the lengths fett is going to in order to make her feel safe, begins to question what someone like him is doing working for jabba the hutt. they talk about morality for a bit and boba actually seems to enjoy talking to her--up to the point where she says he reminds her a bit of han. he reacts angrily, saying he and han are nothing alike. curious about his reaction, leia keeps pressing. why does he hate han so much? boba responds by saying it’s bc han smuggles spice. leia is like, “dude, seriously? you literally kill people for a living.” boba gets increasingly, uncharacteristically loud and agitated arguing with leia about why smuggling spice is worse than murder and is one of the worst things a criminal could sink to. and then, finally, at the crescendo of their argument, he snaps at her, “If I had been using spice tonight, Leia Organa, perhaps you would not be safe with me in this room.”

so, uh. what the fuck, right? apparently the reason boba hates han is bc han smuggles spice and spice... makes people more likely to be rapists, according to him??? what???

moran doesn’t fully answer these questions in the story, though he drops some major hints--the beginning few scenes show boba as a young man in jail for murdering a man named lenovar, his superior officer in the journeyman protectors, and staunchly refusing to say why other than that lenovar deserved it. this is followed by a scene maybe a couple of years later with boba literally burning a spice lord’s palace to the ground. this is all the context moran provides, but, the story doesn’t end there as later EU writers would keep this peculiar bit of characterization and expand upon its background.

which brings us to the backstory that post-aotc legends writers eventually settled on: when boba was 16, he began to feel dissatisfied with his life as a bounty hunter. he befriended another teenaged bounty hunter who felt the same way: sintas vel. the two of them ended up eloping to concord dawn, his father’s home-planet, and tried to live “normal” lives or as normal as two teenaged former bounty hunters could manage. boba got a job as a journeyman protector, where he was taken under the wing of a superior officer named lenovar; boba and sintas even had a daughter, named ailyn.

for awhile, everything seemed fine, but, of course, this contentment was not to last. lenovar turned out to be a scumbag predator who, after gaining boba and sintas’s trust, sexually assaulted sintas. fearing what might happen to her young family if she tried to retaliate, sintas attempted to keep the whole thing a secret. however, boba eventually found out and immediately ran off to murder the shit out of lenovar. combined with the details from moran’s story, the implication is that lenovar was a spice-user and/or that he attempted to use spice as an excuse for his behavior when boba confronted him. either way, after murdering lenovar, boba was imprisoned for killing his superior officer. however, in an effort to protect sintas, he refused to say why he did it and instead just insisted to his interrogators that lenovar deserved what he got and that he felt no remorse for killing him (retroactively explaining the scene at the beginning of “the last one standing.”)

boba was subsequently exiled from concord dawn and his family, leaving him with bucketloads of unresolved issues regarding relationships, sex, and spice. i would say that it would be perfectly reasonable if not outright supported by legends material to view boba’s apparent disapproval of casual sex in moran’s short story as his own thin self-justification for deeper issues that have nothing to do with space catholicism and everything to do with All That Shit that happened to him and sintas when they were teenagers.

at the end of the day, technically all of legends/the expanded universe has been retconned, so feel free to take as much or as little of this as you’d like for your own personal boba fett canon. i just wanted to provide some alternative interpretations of that line other than just “boba fett happened to be space catholic, i guess”

#boba fett#drugs mention ///#rape mention ///#honestly nothing is canon anymore so just choose whatever explanation you like best and run with it#up to and including ''he literally never said that shit''#i'm just incapable of NOT infodumping about legends!boba fett lmao

309 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

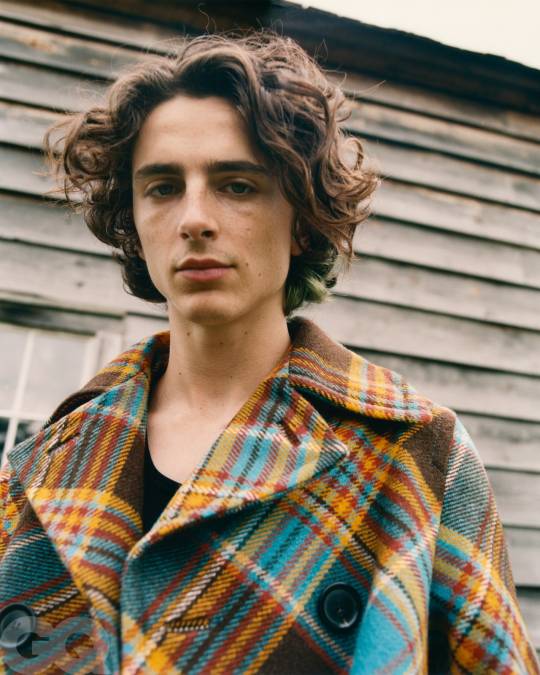

The Making (and Re-Making) of Timothée Chalamet

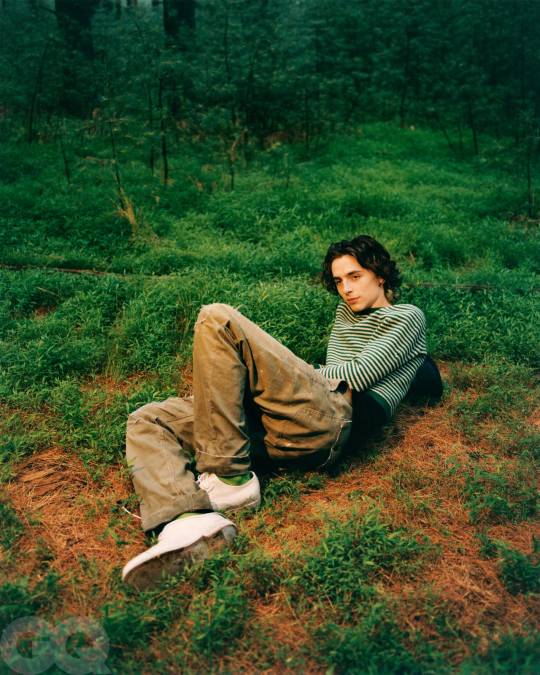

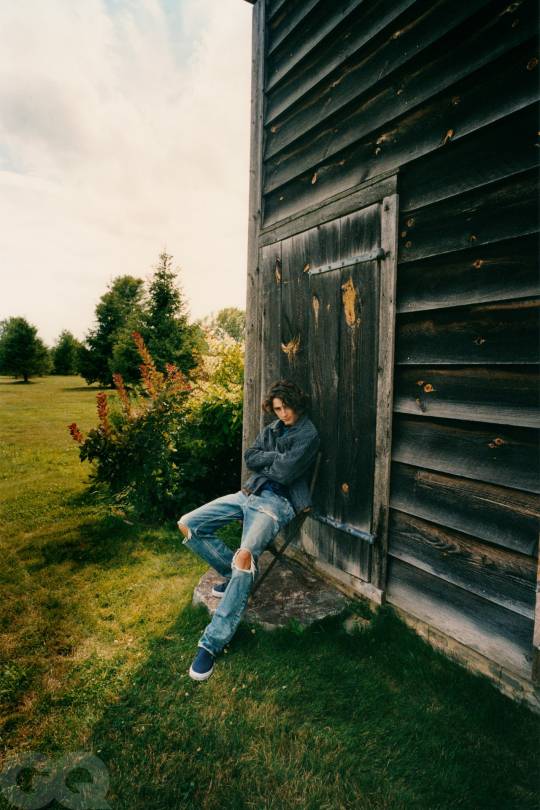

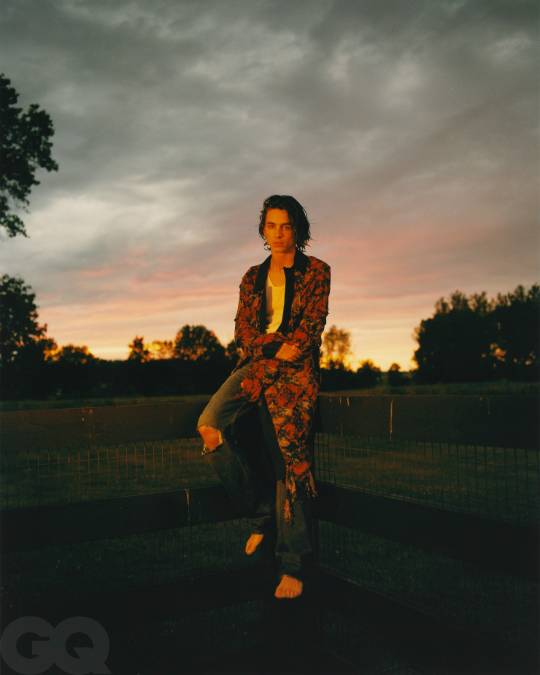

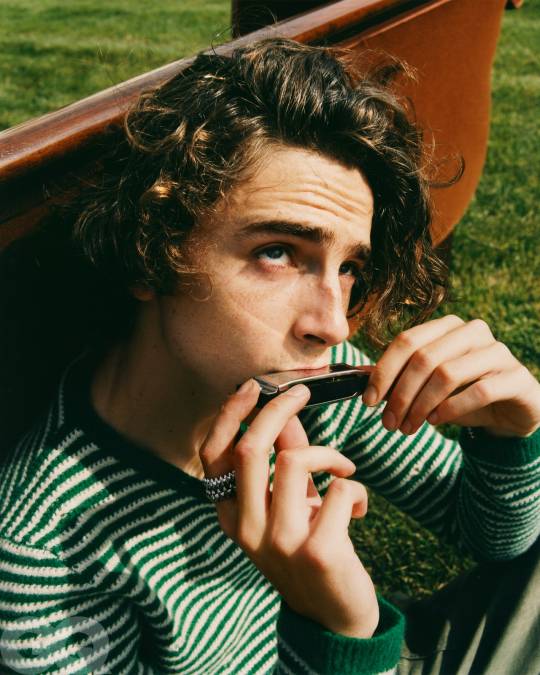

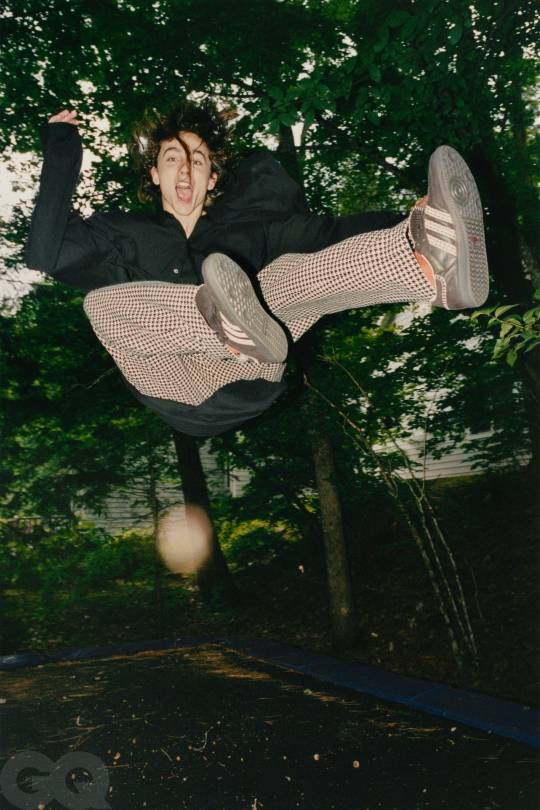

BY DANIEL RILEY / PHOTOGRAPHY BY RENELL MEDRANO

He found superstardom and artistic acclaim instantaneously. Now, with unique candor, the actor of a generation reveals what it’s like to come of age in our very upside-down era.

The day after the Oscars in 2018, everything that had changed, changed back again. Timothée Chalamet had spent the previous months becoming known. He had acted in a film, Call Me by Your Name, which was critically acclaimed as well as an instant object of cultish admiration—and his performance had made him, at 22, the youngest person nominated for best actor in 80 years. He had, simultaneously, been transformed into the rarest of pop confections—fawned over by younger women, older men, and every demographic in between. And he had traveled without pause on the awards circuit since early autumn, back and forth from New York and Los Angeles, practically living out of the first-class lounge and the lobbies of the Bowery Hotel and the Sunset Tower.

But the day after the Oscars, the moment the clock struck midnight and his carriage turned into a pumpkin, Chalamet was right back where he'd been before the whole fantasy had begun: in New York, with no credit card, no apartment, and no longer any structured demands on his time and attention. Outsiders who had witnessed the arrival may have regarded this 22-year-old as being in possession of wealth and clout, but he was suddenly back on his own dime, which amounted to maybe five or six dimes, reticent to stay with family and friends whose lives he felt he was disrupting with all his new baggage. Of course they couldn't possibly comprehend the chemical reaction that had just transpired. They were still hydrogen and oxygen, and Timothée Chalamet was all of a sudden water.

And so, for three weeks, he disappeared into the wallpaper of the Lower East Side. Specifically, the wallpaper of a little apartment that the French street artist JR kept for visiting collaborators. Chalamet holed up against the ugly New York weather of late winter, and did the only thing he could think to do: learn lines. The King would be his first film since his pivot into fame, and he was anxious to get back to acting after such a long stretch of merely talking about acting. Even more, he needed to blot out the unrecognizable icon the internet was already beginning to make of Timothée Chalamet.

I met Timothée for the first time at the onset of that initial blush of fame, when all of us were being introduced to an actor who had both rare talent and the un-engineerable it that chings like an audible sparkle off a jewel in a cartoon. I wrote a story for this magazine about that first chapter in the arrival of a film star. This is the second chapter, the story of what's happened since. It wasn't evident yet, but those three weeks in New York in 2018 were the starting line of what would amount to a 30-month stretch of four new films, two new Oscar campaigns, some refreshing romance, an incessant awareness of the confusing image of himself as—what else to call it?—an emerging global movie star, and a constant concerted effort to figure himself out as both a young actor and a young person in the unceasing spotlight.

This summer, we were talking about all this on a little screened porch out back of a modest cabin in Woodstock when Chalamet recalled those three weeks. “My world had flipped,” he said. “But if I kicked it with my friends, things could still feel the same. I was trying to marry these two realities. But I don't even think I knew that was what I was doing. That dissonance was real. And thank God. Because I feel like if I'd caught up to it immediately, I would've been a psychopath or something.”

Out on that porch, I asked him a version of the same question over and over: What had the last two and a half years been like for him, as a human being? His response was a multi-hour monologue that I would characterize as: intense. He expressed unadulterated gratitude for his great good fortune. But he also expressed confusion and tension. He is firmly in a moment when he is concerned that everything he says or does or thinks will look or sound wrong. He backtracked a lot (“Wait, let me try that again”). He jumped on and off the record (“Sorry, sorry, sorry, this is just for you…”). It was important for me to know, he said, in order to communicate the context of his experience, if not the specifics.

.

“I want to get back to the undefined space again. I'm chasing a feeling.”

He lives in the same world all of us do—only with the potential for adoration and blowback turned up to 11. He seems, at once, to trust his own instincts while also second-guessing most thoughts the moment he's convinced of them. It is an exhausting way to be. At times, when he was up on his feet, in his T-shirt and shorts, pacing around the little screened porch, hands tugging at his mane, I could feel the gears grinding to the point of smoke. He wanted so desperately to get this right, to express what he really meant, to feel the right feelings, to live the right way, to be the right kind of man for the people in his life that he knows he can and should be, despite everything else, despite the noise. He's doing his best.

Timothée had rented the house for the month of July, as a little escape but also as an opportunity. He was slated to play Bob Dylan in a new biopic. No telling when it might film, given everything, but for now he had more time to himself than he'd had in years, which meant time to maybe huff the vapors of some Woodstock Dylanalia. “It's not like I'm suffering from lack of connection otherwise,” he said, “but it just really feels like I'm connecting to something here.” When he arrived, he discovered that his little house had a wall devoted to Dylan—to the albums he'd recorded in the run-up to his timeout in Woodstock in the late '60s. Timothée relished happening upon that wall his first day in the Airbnb. The universe offered signs if you nudged it toward coherence.

He knew what the cabin might seem like—like some young actor taking himself way too seriously, “treating himself like an artist.” But he was back and forth between Woodstock and New York all month, bombing up and down the interstate in the Honda sedan he'd rented from Enterprise. (He learned how to drive on Beautiful Boy.) All the while Dylan was top of mind. Timothée was late to the party but helplessly obsessed. He quoted him generously. He fixated on both the art and the persona. He marveled at the way the artist could be out there so much, making such an impact, while also keeping the real person obscured behind the music, the characters in the songs, the language. In the city, we spent time walking around Greenwich Village, Timothée in an identity-concealing face mask and bucket hat and sunglasses, able to search out old Dylan addresses in an invisibility cloak. He ran from site to site, with notes he'd kept while reading Dylan's memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, barreling up stairs and peering into windows. He was a 24-year-old actor, taking advantage of the pause between the second phase of his career and the third and thinking hard, daily, about how to play the next few years.

He rented the house in Woodstock, too, so that he could have a little space all to himself. He craved the privacy to try things and to fuck up. To make small mistakes now, out of view, when it was just him, when he was still young, so that he didn't have to worry about it later. At one point, he stood up and slapped an empty water bottle off the table so that it clattered against the screen of the porch. “I want to know what that sounds like!” he shouted. He hadn't taken many missteps yet, and it made him uncomfortable, wary, that he would someday. The month felt like a controlled burn. In the most innocent way, that was what Woodstock was about. He got to practice his guitar and harmonica in peace, cook himself his “shitty pasta” without judgment, permit himself space to keep growing up. So much was in the spotlight now. But in that cabin, he could sit on the couch for a while and re-familiarize himself with “the crease in the cushion” that he'd lost touch with over the past few years. The quiet. The stillness. That sunlight there coming through the trees. He could breathe a little. Sleep a little. It had all been so good for him so far. But the goodness made him anxious. When will the other shoe drop? Not there. He'd deleted Instagram off his phone. He'd stopped posting on Twitter. He was reading again. Listening to albums all the way through. Slowing down. What was it like to have lived these past two and a half years? It was like a lot of things, but here at the end of it, it just felt good to sleep.

Back at the start of the 30-month run that led to Woodstock, Timothée turned over the keys to JR's studio and went to Europe to shoot The King. The role was like none of the films he'd just received notice for. “Here I am on set with all these Hungarian men with scars on their faces, and they're like, ‘You're the center of the shot, you're the badass! And we know you tried to put on all this weight, but like: You're wearing all the chain mail.’ If they took the chain mail off, my throat is still this big…” There he was trying to keep in perspective this new fame, this new validation, this new temptation toward ego, all while being thrust into the center of “something called The motherfucking King.”

When he returned to New York that summer, he skipped off the atmosphere again with another awkward reentry. One moment he was on the battlefield of the biggest-budget drama he'd yet experienced, the next he was “back in New York, on the A/C/E at Port Authority, just like, What the fuck is going on?” It was a pattern over the past few years. The calmly intense immersion into work, the “thud of lost purpose,” as he called it, when the work ended. It happened the same way in the fall of 2018 with Little Women—reunited with Greta Gerwig and Saoirse Ronan and the crew from Lady Bird. There was just an ease with which he plugged in with them, “a vocabulary of friendship” that existed there.

Timothée's career thus far has been filled with these sorts of friendships, notably those across generational lines. Even a casual observer may have picked up on it. Those glommings-on to older people in his life. Armie Hammer. Kid Cudi. Greta Gerwig. When I asked Gerwig to comment on the arc she's witnessed up close, from Lady Bird to Little Women, she wrote a note about “my friend Timmy”: “It's hard for me now, because I'm his friend, to see him strategically.… I love talking to him. We can get on the phone and talk for an hour or more without even realizing it, just skipping from subject to subject, making jokes, me feeling old and happy and him being funny and anxious and delightfully all over the place.” It's an odd gap he finds himself in—forced to be more accelerated than most 24-year-olds while also having not lived enough life yet to fit in absolutely with the people he enjoys spending time with most. On a recent visit with his grandmother in New York, she surprised him by saying, “I wish you would hang out with people your own age more often. It must be so weird.” It made him chuckle. Even she'd noticed. She might be right. But how could he resist the orbit of these creative geniuses he'd so long admired and who were filled with so much knowingness?

“I'm confident in the way I'm trying to approach things now, how I'm setting up the angles.”

In the winter of 2019, another Oscar campaign left him feeling disoriented all over again. Everything, Timothée said, was exactly the same as the first time except him. He'd put in this undeniable performance, but maybe one that sparked a little less for Oscar voters than that first kiss with a stranger. Now he was in all the same rooms as before, the same lunches and dinners and cocktail parties, shaking hands with the same Academy members who showed up at everything to get a little nibble of the freshest biscuit, growling ominous things at him, like: You don't have my vote yet.… “I really don't know how to talk about this stuff, man,” he told me, “because my experience of it is at the center of it. There's just some dark energy at these things, and this time around I felt like I could see it. And yet I'm thinking, Why isn't this going the exact same way?”

He wasn't nominated for Beautiful Boy, but the fresh air came, as it always seemed to, on the set of the next film: Wes Anderson's The French Dispatch. The movie is about a fictional English-language magazine (based on The New Yorker of the midcentury) and is structurally organized like the magazine itself, featuring short pieces at the “front” of the movie and a triptych of long features at the back. Timothée costars in the second feature, about a May '68-style student-protest leader named Zeffirelli and the middle-aged magazine journalist (Frances McDormand) assigned to report on his cause.

“I had seen Timmy in Lady Bird and Call Me by Your Name,” Anderson wrote to me, “and I never had the inconvenience of ever thinking of anybody else for this role even for a second. I knew he was exactly right, and plus: He speaks French and looks like he might actually have walked right out of an Éric Rohmer movie. Some time around 1985. A slow train from Paris, a backpack, a beach for 10 days in bad weather. He's not any kind of type—but the New Wave would have had a happy place for him.”

The privilege of early fame that Timothée most appreciates is the ability to choose the directors he works with. His role in The French Dispatch is a minor one, but it's a Wes Anderson movie—it's as simple as that. Due to the episodic nature of the film, some of the other “stories” were already being shot when Timothée arrived in Angoulême, a town that reminded him of the one he spent time in growing up, “so French it was like a caricature,” he said. Timothée had the opportunity, then, to hang with some of the elders he doesn't act with, like Jeffrey Wright, Bill Murray, and other seasoned members of the Wes Anderson troupe. “It was immediately as if it wasn't his first time with our group,” Anderson explained. “He was somehow already part of the family. The youngest member.”

Timothée had seen McDormand around for years, but he'd never felt like she was someone he could approach. “We'd shared an agent,” he said. “And it was no disrespect to me, but I hadn't been in any movies yet. What business do I have talking to Frances McDormand? But now, and this is the gift of acting, I really feel myself coming into my own as a community of thespians, as opposed to actors. And man, that sounds pretentious, but I just mean it's not about the fucked-up ladder of success and un-success, and being the guy or the girl, and then being off the list… That's not what I'm talking about with her on set, that's not what she's espousing to me. She's talking about a long career. She's talking about marriage with a creative partner and consultant. So to be able to have conversations like that and then a story line in the movie where they're kind of on an equal field? Even if she's an experienced, wise woman and he's an idealistic, naive boy? That's the exact relationship of exchange I want with my intergenerational peers.”

There's a particularly memorable scene in The French Dispatch, reporter and subject having fallen into bed together, when there's a knock at the door. Timothée looks at McDormand, anxious about who's there, mortified when McDormand informs him it's his mother. There, in that scene, we see all the desire of Zeffirelli—this energetic young man with all the right intentions, who strains to be intellectually and emotionally riper—clash with the reality of his age. It felt familiar to me, and no doubt to Timothée. It was some of my favorite acting in the film. I asked McDormand if there was anything in their scenes that struck her as particularly mature for someone his age. “Maturity is not something a fellow actor is the most concerned with,” she said. “Playfulness, discipline, and rigor. I do recall, during our scene in bed, the crew responding to his work with true respect for his focus. He was bringing it and we sat up and paid attention.” Anderson added: “I think my favorite moments with Timmy during a scene were the ones where I saw him pause and find a new attack. A new angle, which he does very clearly and assertively. What I love is how he will surprise you with something new, completely unexpected and perfect.”

One night, while McDormand was shooting a scene without Timothée, her husband, Joel Coen—he of the Brothers—asked Timothée if he wanted to go out for a steak. Over dinner, Timothée grilled Coen about Dylan. He knew Coen was a fan and had steeped in it on Inside Llewyn Davis. “He almost seemed weary of even talking about this stuff, it was so big and potent,” Timothée told me. But Coen noted that the truly incredible thing about Dylan was not so much the quality, which was obvious, but the quantity—the rapid amount of work in short succession, one groundbreaking album after another, in those early years. That takeaway resonated deeply with Timothée. Especially as he reflected on it from summer 2020, during the pause, during the moment of no work. That gush from Dylan made him want to work—harder, longer, better, more.

A week after our conversation in Woodstock, Timothée and I were in New York City, sitting on a bench along the Hudson, talking about what he's looking for when work resumes. “I want to get back to the undefined space again,” he said. “I'm chasing a feeling. When you think you're doing some great thing, it's probably something you've done before, and when you really fucking have no clue, that's when you're doing something on the edge, good or bad.”

Timothée's mask had slipped down his face as he was saying this, and two young women, about his age, approached cautiously. “Would you mind if we got a…,” they asked, and he hopped up without hesitation. “How'd you recognize me?” he said, friendly, but genuinely curious, as if he hadn't just been shouting about art in a voice that sounded a lot like Laurie from Little Women or Timmy from late-night shows.

“Was it the scrawny limbs or the hair?” I asked him as he sat back down.

“Definitely the first.”

From France, last spring, it was straight to Hungary—right back to the exact apartment in Budapest he'd stayed in while shooting The King—to start work on Dune. Very few actors had become as famous without a blockbuster. And while he'd really gotten it down how to act on an indie set, how to make every second and every take count, he knew this would be something altogether different. It wasn't just the shoot that would prove taxing. A film of Dune's scale would likely be the can opener to a whole other stratum of Hollywood prominence.

Director Denis Villeneuve told me Timothée was his “first and only choice” to play Paul Atreides, “the one name on the page.” When they met to discuss the prospect, Villeneuve told Timothée how happy he was to finally meet the young actor. And Timothée had to remind him that they'd met before, when Timothée read for Villeneuve's Prisoners. “ ‘Of course!’ ” Villeneuve remembered. “He did a great audition, but he didn't physically fit the part. He was probably swearing at me because I didn't take him.” Timothée was party to so many stories like that one—glancing interactions with these heroes of his before he'd broken through. It reminded me of the relationship between freshmen and seniors in high school. The freshmen remember everything about the seniors; the seniors hardly notice the freshmen. But we all become peers eventually.

“I felt there was one being on this planet right now that would be able to portray Paul Atreides,” Villeneuve said—referring to the hero of the 1965 Frank Herbert novel, who transforms from an unassuming heir into a messiah figure, a charismatic outsider and commander of men and women (and sandworms). I read Dune for the first time this summer and was shocked by the source material, how much I'd consumed in culture that had borrowed from it. Star Wars. Alien. The Matrix. Game of Thrones. Paul, therefore, is a type we're familiar with but also possessing singular characteristics Villeneuve wanted Timothée for: “He has a deep, deep intelligence in the eyes. Something you cannot fake. The kid is brilliant. Very intellectual, very strong. And you see that in the eyes. He also has a very old soul. You feel that he has already lived through several lives. And at the same time, he looks so young on camera. Sometimes he'd look almost 14 years old. He has this kind of general youth in his features and the contrast with the old-soul quality in his eyes—it's a kid that knows more about life than his age. Finally: He has that beautiful charisma, the charisma of a rock star. That Paul will lead the whole population of a planet later. Timothée has that kind of instant charisma onscreen that you can find only sometimes in the Old Hollywood stars from the '20s. There's something of a romantic beauty to him. A cross of aristocracy and being a bum at the same time. I mean, Timothée is Paul Atreides for me. It was a big relief that he agreed, because I had no plan b.”

“If I get hit by a truck next week, I'm looking at 20 to 23, I don't know if you can top that.”

I asked Villeneuve if he noticed Timothée struggling at all to adjust to the larger-scale production. “It didn't show when he was on set, but I think for him the big thing was to learn how to create his own bubble on set. So that he would not have to try to be the friend of everyone. When you're on a smaller set, when there's 25 people, you can be friendly with 25 people. When there's 800 people around, you cannot be friends with 800 people.” He chuckled. “It's too much. So how to save your energy, how to focus, how to give himself permission to be in his bubble and make sure that his bubble is respected.”

As ever, Timothée had a special affinity with those people on set who were a little older, a little wiser. Villeneuve said Timothée was constantly speaking with him and his wife in this open, vulnerable way about his concerns, his fears, how to deal with certain pressures. Villeneuve also described for me Timothée's relationships with his fellow actors, particularly the trio of Josh Brolin, Oscar Isaac, and Jason Momoa. “I felt like Timothée was deeply seduced—or maybe not seduced, but I just felt it was like a kid being with older brothers,” Villeneuve said. “He was younger, he was the little one on set, and everybody loved him. There's a scene in the movie where Timothée runs into the arms of Jason Momoa, and Jason grabs him like a puppy and lifts him into the air like he was a feather. And that's real! They really loved each other. It was very beautiful to see this young man being influenced by these people he admires.”

“His positive energy is infectious,” Zendaya, his nearest peer in the film, told me. “He really is so much fun to be around. We have very similar humor, and we can keep a joke going for a long time, but when the cameras start rolling and it's time to work, you can see it's game time, and he just taps into this brilliant intensity. It's awesome to witness.” Villeneuve underlined the energy as well, describing for me just having seen Timothée the night before we spoke, and marveling at “that beautiful, strong candor.”

“I will say that looking at Timothée working, I had a deep feeling that I was watching the birth of something,” Villeneuve added. “Not that it's for me—I say that with humility, because I feel that birth in all the movies he's done so far. I'm feeling it's someone that has insane potential. When I say potential, I don't want to reduce what he's doing right now, not at all. It's just that sometimes you are in front of somebody and you have the feeling you are in contact with a strong artist and that artist, his identity is still growing, building itself, learning its boundaries, learning how to protect some part of it. I think that we are witnessing something beautiful right now.”

At the end of summer 2019, Timothée finally resurfaced from Planet Dune. He had been on social media only sporadically while shooting for most of 2019, and so, for his vast base of fans, it was an overdue glimpse of the object of their affection. First up was the Venice Film Festival and the premiere of The King. There were clothes and Kid Cudi cameos and charming red-carpet interviews. It was an example of the sort of stretch, in the gaps between shoots, when Timothée could indulge his passions for hip-hop and fashion and all these things he'd loved all his life that were suddenly accessible. It was another of the delirious disorientations of the past few years—the way that people who were once subjects of his intense fandom were suddenly a part of his life as friends or acquaintances happy to have him around. He might still embarrass himself at times, helplessly rapping back lyrics to his hip-hop heroes or gushing like a broken dam about new music or clothes or art made by the makers in his life, but they were cool with him so long as he actually kept his cool.

Timothée also spent the end of last summer promoting The King, alongside his costar Lily-Rose Depp, whom he'd been dating for about a year. He is serious about keeping his former relationship with Depp to himself, but he did share one very sweet, very funny, very sad anecdote that encapsulates the spectrum of great and terrible that accompanies the private life of someone new to mega-fame like Timothée.

After Venice, he and Lily-Rose took a few days for themselves in Capri, where they were photographed by paparazzi. One image, in particular, circulated in which they were making out on the deck of a boat. Timothée is contorting himself into the kiss and looks a little awkward. Many people had their laughs. And some even suggested that the photo was staged for publicity. “I went to bed that night thinking that was one of the best days of my life,” Timothée told me. “I was on this boat all day with someone I really loved, and closing my eyes, I was like, indisputably, ‘That was great.’ And then waking up to all these pictures, and feeling embarrassed, and looking like a real nob? All pale? And then people are like: This is a P.R. stunt. A P.R. stunt?! Do you think I'd want to look like that in front of all of you?!”

This was how things worked now. He'd disappeared into those four straight films and emerged into a new paradigm—one that followed him into the holiday season of last year and a whole new level of exposure with Little Women. Here was this film about sisterhood, female intimacy, and a feminist critique of art and commerce. And yet Timothée was still the shiniest object in the set for so many fans. “I'm very used to answering questions about Timothée's hair from 15-year-old girls,” Saoirse Ronan joked with me. “I imagine that's probably what you're going to ask me about?”

Ronan has the unique perspective of having filmed and then promoted two movies with Chalamet during the past three years, and has as clear an eye as anyone onto this early phase of his career. “He's had such incredible opportunities, and he doesn't let the reality of that pass him by,” she said. “He's incredibly gracious and grateful in relation to his work and the people he works with. I think he's become more open as an actor. He knows his instrument more. I think he works even harder now because there are projects that are on his shoulders in a way that they weren't before. And of course he's been totally catapulted into this whole other realm of attention and notoriety. So he's also having to balance the incredible fame and attention, which would completely freak me out if it was something I had to go through.”

.

“I've realized that as much as these heroes of mine mean to me, and as grateful as I am when they offer me advice, even they acknowledge it's just a different thing now.”

When Timothée and I were sitting by the Hudson that afternoon back in summer, there were those two young women who approached him for a photo. But there were also two other young women who caught an eyeful of his profile as they strolled by and then surreptitiously positioned themselves out of his sight line but still in mine. They did that thing where one pretends to take a picture of the other while actually shooting back over her shoulder in selfie mode. That charade went on for five minutes or so while Timothée exercised his guts about reuniting with Gerwig and Ronan on Little Women, and though I was nodding along, I was also marveling at the lengths to which those two fans were willing to go to get a picture of him.

I asked Ronan what she's noticed about that level of attention, sitting beside him for so much of it. “I'm always kind of shocked by those things—when any one person can just completely take over people's lives so much,” she said, laughing a little incredulously. “But I'm also not surprised. There just aren't many other young male actors out there like him, who are able to hold an audience in the way that he does. His look is so magnetic and beautiful. One of the things that we spoke about a lot when we were doing Little Women, in terms of our characters, but also in terms of myself and him as people, is that we both have this masculinity and femininity equally. And I think that that's one of his strengths, is that he can be incredibly sort of feminine and sensitive and sensual, and also he's a guy that, you know, girls fancy. So he covers so much ground in terms of popularity. But at the end of the day, he's always gonna have this skill. He can be cute, but that only gets you so far.… And so I've seen him learn how to separate himself from all that other stuff when he's on set, when he's working.”

In Woodstock, Timothée had described to me with greatest admiration the way that Ronan can act in these films, at this highest level of acclaim and attention, but also remove herself, uncomplicatedly, from all the fuss: “She is like a superhero when it comes to this sort of thing, going through it so healthy—with the asterisk being excellent work across the board and four Oscar nominations. I think her, like, DNA of self is really morally right.” She knows herself extremely well, he said, and has the confidence to give up only so much of herself. Whereas he feels he is calibrating constantly how much of his true self to reveal. “Saoirse's one of my best friends in the world—at least I think we're best friends. And she's never judged me for…the Coachella of it all.” That is, the part of him that can't resist fanning out backstage with his favorite musicians or occasionally allowing himself to be in the spotlight even as he talks about preserving his privacy.

“He's 24, and he's gonna have a great time, and I would never judge him. I've been to Coachella; I just never got photographed at Coachella,” Ronan said, chuckling. “But yeah, we talk about that sort of stuff all the time. We've weirdly gone through this together for the last few years. We've both become more accessible. But he's had one sort of attention—I do feel like boys get it on a whole other level. I know that ultimately what he wants is to be good at his job. And that will always steer him on the right path. I've always let him know, and he's always let me know, we can talk to each other, and we do. He has good people around him, and I'm one of them, and Greta as well—we all kind of look out for one another.”

Timothée spent late May and early June asking questions of himself: What can I do? What is my role in all this? He felt conflicted when he sprang to action and conflicted when he stood still. But never did things feel less uncertain, less self-conscious, than when he was marching, anonymously, alongside hundreds or thousands of others in Los Angeles in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. It was an active way to participate—meaningful action, without being showy, without flexing any of the levers of fame or power. He was going to get hit no matter what he did, so he tried to follow his instincts of what felt humble, responsible, right.

“This idea,” he said, “that power is the mass body politic organized—and how many bodies can you get together—that makes sense to me.” He didn't disappear but, rather, stripped himself of his him-ness and became one body, among many, taking up space and participating in an unequivocal statement. “With a mask, a hood, a hat, glasses—my face is deleted,” he explained, “and I'm literally presenting a physical form, you know?” A single body in space that, like a vote cast in an election, is democracy embodied, but anonymous. The same unit of power as anyone else. “People might find it disingenuous, but I found it really grounding,” he said. “It was Oh shit, I don't feel out of place—and yet I haven't been in a crowd like this for years.”

He spent much of the summer talking with others about how a person should be in a cultural and political moment such as this one. “After a day of protests,” he said, “I'd ask friends if they ‘felt good.’ If we do, is it a good thing to feel good, or does that mean we're doing it for the wrong reasons? How much do I want to put on social media? Is it a virtue signal to put it on social media? But all social media is performative, right?” I heard him ask dozens of self-interrogating questions like these. He cares so genuinely about doing the right thing, about doing well by his family, his friends, and his fans. But he didn't want to misuse his privilege or his platform, to overreach so that the gravity of his fame sucked up anything from anyone else whose moment it was to speak. He didn't want to take up room; he wanted to help center other voices. On Instagram, he posted videos each day during the first week of marches in Los Angeles—no directives into camera, just an implicit charge to his followers: Show up. Listen. Be a body.

“I have so many thoughts on so much of it,” he said, “but I don't see the benefit of putting it down for consumption until I've really worked out exactly how I feel about it all. Who benefits from my half-baked ideas?” Who cannot relate to this in 2020? Who would want any of their dinnertime conversations with family and friends these past months chiseled into the stone of the internet? “I care so much about this stuff. But I would never want my caring to be misconstrued. I don't want my caring to be about me in any way.”

God, this stuff twisted him up. He knows how much has gone his way. But from the summit of good fortune and power, is it better to speak constantly—or to shut up, put on the glasses, pull down the hood, and live and act according to one's convictions as one individual among many individuals? To march. To vote. To speak through action rather than words. Staying in motion, showing up, being a body—it's a good place to start while he works out the rest of how he's meant to live a life true to his values with everyone watching.

He's seeking out the right path, the right people—with help from his “intergenerational peers” and Dylan and anyone else he can find. He wants the benefit of their knowledge and experience, and he's okay if it's slow going to accrue it. He's open to playing the role of the novice still. But there have also been things in his life these past of couple years that have made him realize, as he puts it, “adults are just kids a little bit older.” When he returned to New York from Los Angeles this summer, it wasn't to his childhood apartment or to a borrowed living space of an acquaintance. It was to his very own apartment, his first, in a little wedge of Manhattan he loved for being nowhere, but on the edge of several somewheres. He relished the mundanity of setting up his own place. To hear him talk about a first trip to CB2 was like hearing another person talk about their first trip to a movie set. “But I think if people saw what my apartment looked like, they'd be like, ‘Oh! This kid has no fucking clue what he's doing.’ ” He is so young and he is so old. It is his gift. He is so patient when he can suppress being so restless. So careful with the long arc of a career when he can resist obsessing over the instant. He is so confident when he centers on the work and so searching when he gets sucked down into questions about the rest of his life. Will he always be this way? This pliable and open? This self-reflective and intentional? He trusted so little of his new life, but he trusted his talent. That was the key. He knew he was as good as anyone at playing other people, even if he was still figuring out how to play himself.

We spent a good amount of time in Woodstock and in New York City and on the phone talking about where his career might take him from here. With great humility, he acknowledges his skill. But he has been thinking a lot about the difference between preternatural talent and mastery—the work that's required to ascend from that floor of young greatness to the ceiling of realized potential. That said, he's wise enough to know that his career could pivot in an entirely different direction—that the world could change or the opportunities could dry up or “eventually there's gonna be an Oscar Isaac in his 30s who's gonna bust out of Juilliard who's gonna be the next great actor and make me feel like a piece of shit. But right now…”

He told me, “If I get hit by a truck next week, I'm looking at 20 to 23, I don't know if you can top that.” To show up with Call Me by Your Name—he knows that that film was a unicorn, the sort an actor works his whole life to find. And the immediate Oscar nomination had freed him up to not spend the rest of his career chasing a certain kind of role that might lead to a certain kind of validation. “I'm not gonna be bashing my head against a wall trying to prove that I'm an actor,” he said. “The train can run over my leg and leave a track forever, and yet the point of entry for me…,” he said, trailing. “That's a good feeling.”

He looks at all these careers—all the careers you might expect: DiCaprio, Bale, Phoenix, Depp. And he does his best to separate the strands of each of their careers that might still apply to his. But all of the rules for acting success that those performers played by, for how to be in the public eye, for career arcs and longevity—those rules are irrelevant now. Hollywood is different, the media is different, fans are different, movies are different, the world is different. “I've realized that as much as these heroes of mine mean to me, and as grateful as I am when they offer me advice, even they acknowledge it's just a different thing now.”

And so it's occurring to him that the next few years will be Timothée finding the path that's right for him. Lately, he's thought about this next phase as shining a flashlight into the dark. There are potential projects that excite him considerably, some of which he's had a greater hand in engineering. There is, of course, the Dylan movie. But there's the question of how to spend the rest of the year, when most Hollywood productions are still paused. “The rest of the year,” he says, “I'm just thinking about Trump, man.” But after that…maybe Europe for a while? The Woodstock experiment did what he'd hoped it would—a little space, somewhere else. He would love to just breathe some different air again.

He was at another pivot point, as he had been when he and I were first together for Chapter 1. In the winter of 2018, the work had been validated, the public profile had developed suddenly. But the temptations, the confusion, the money—those were all lagging indicators. By mid-2020, all had caught up. And the money, in particular, was on his mind one afternoon in New York. We were talking about how a person might stay true to one's roots with that sort of thing when the reality, for him at least, had changed with Dune. I told him that one of the things that seemed to differentiate him from young stars of the past, and perhaps was a feature of his generation, was the way that material possessions didn't consume him. He didn't buy much stuff. He didn't own a car or a house. He liked borrowing clothes, but not necessarily keeping them. He agreed with the characterization, but then got immediately twisted up about a potential future hypocrisy: “But Dan, what if I do grow to like fancy shit?!”

Boomeranging back home after the surreal adventures out in the world—that was a good and grounding thing for him. Over the weeks we were talking, he spent time with his folks, delivered some COVID groceries to his grandma, and was in touch with his sister daily. And in New York, he and I kept running into ghosts. One afternoon, when we crossed the West Side Highway at Houston Street, he gestured at the athletic complex at Pier 40, where he played soccer growing up. He scampered over to a vending machine there to grab a bottle of water. When he pulled open his wallet to pay, he had only twenties. “Bad metaphor! Bad metaphor!” he screamed, jumping away from the vending machine, as though it were one of the great threats to his selfhood. This was the sort of innocuous moment that will hum with outsize resonance for me when I think about Chapter 2 from the future. All the things that one would expect to happen had happened in the first two and a half years since the arrival of a comet, and yet he was suspicious of so much of it.

Here is another way I will remember him from this moment: sitting on that porch in Woodstock—breeze and birds in the trees, sunlight in the leaves—looking for a higher power. Or at least expressing openness, as a nonreligious person, to the idea of some central organizing force in the universe—because, given everything lately, there has to be or we're fucked, right? Some of these searching things he said to me could be mistaken as a person spinning out a little. But that wasn't it at all. There was such calm. There was such contentment with the grace that had been afforded his life and career thus far, and where each might take him next. He was questing, yes—but he was firmly at the controls. The flashlight in the dark. Someone moving forward with great confidence into the unknown, with eyes wide, mouth shut, and ears listening more than they ever had before. There were no models for how a person like him should be anymore. There were no longer any adults who weren't just kids a little bit older. There were no blueprints for how to shape a career—so much had changed. There was only a head and a heart, his, and a feeling for the moment. “Maybe I'll never do a great work of art again, but I just feel like I'm confident in the way I'm trying to approach things now, how I'm setting up the angles,” he said on that porch in Woodstock. “When you think about Dylan. When you think about what Joel Coen said about the rapidness of the art, I'm just like: Trust the beat of your own drum. Give this its best shot. Give your artistry its best shot.”

.

Daniel Riley is a GQ correspondent and the author of ‘Barcelona Days,’ which was published this past summer.

A version of this story originally appears in the November 2020 issue with the title "Wild Heart."

PRODUCTION CREDITS: Photographs by Renell Medrano Styled by Mobolaji Dawodu Tailoring by Ksenia Golub Produced by Wei-Li Wang at Hudson Hill Production

439 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your opinions on the RTD era's companions' relationship with the Doctor? 'Cos personally, they bother me a little sometimes, and I was curious what your opinion was.

Yeah, they bother me a little too. I’m actually going to share some thoughts about the characters themselves, as well as their respective relationships to the Doctor. Partly, I want to do that because not to do so would be an injustice to the characters. So, here goes.

Rose (and Mickey a bit, because you can’t really separate an analysis of their characters and he’s a companion too):

Rose is a charismatic character, and I think just right for relaunching the series. She’s young and displays many of the flaws of young people, yet in other ways is more mature than other adults, including her own mum–indeed Rose is often seen taking on a role of parenting her parent. While Jackie seems content to live off the dole, Rose has a job. It’s not a particularly good job, but she seems to be given a fair bit of trust and responsibility, probably above what her official position warrants, which suggests that she’s earned the admiration and reliance of her boss–and given her home life, that’s not surprising. Rose is clearly used to having to be more responsible than her peers. She’s vibrant, curious, compassionate, and brave.

She also takes advantage of Mickey’s affection for her, perhaps without realizing it (at least at first). She’s pretty judgy generally, and she’s not above using the Doctor as well. This suggests that despite (perhaps in part because of) being brought up by an emotionally immature parent and having to take on a lot of responsibility before she was really old enough to bear it, Rose is quite selfish.

Now, as to her relationship to the Doctor, meeting him does two things for her: it gives her an apparently easy escape from a life she feels trapped in, and it gives her the opportunity to develop a relationship with someone unlike anyone she’s ever known, who seems to see potential in her far beyond what any other person in her life has ever shown (especially Jackie and Mickey), and who is both willing and able to protect her and to care about what she feels and wants. Am I saying the Doctor started out as more of a parent-substitute than a boyfriend? Yes I am. Is that kind of creepy? I think so. But not necessarily more creepy than him being her boyfriend, given the age gap.

OK, so Rose gives Mickey a kiss and obliquely tells him “thanks for nothing” before swanning off with the Doctor. By the time she comes back, a year has passed for everyone she knows but just one day for her. This causes ENORMOUS problems for Jackie and Mickey in particular, and she does seem genuinely sorry (well, sorry to Jackie–she seems mostly annoyed with Mickey’s anger AT BEING SUSPECTED OF MURDERING HER. BECAUSE SHE RAN OFF WITH AN ALIEN). This gets swiftly brushed aside by alien shenanigans, and Rose swans off again–leaving Mickey apparently in some doubt as to their relationship status. The nature of her relationship to the Doctor is also left ambiguous at this point, but she’s clearly not thinking of him as “substitute for parental acknowledgement and affection” anymore. She flirts like crazy with Jack who flirts like crazy with both her and the Doctor and both she and the Doctor seem vaguely jealous of the other’s attention to Jack. Back to Mickey meeting them in Wales, who apparently STILL DOESN’T KNOW that Rose has basically dumped him, and does she make that clear? No, but the Doctor is acting more and more like a jealous boyfriend (and really doesn’t stop treating Mickey like garbage until the poor guy saves them and stays behind in Pete’s World, thus earning his respect, I guess, and also removing the threat), and none of this is Mickey’s fault. He’s astute enough to see, at least, that the Doctor and Rose’s relationship is destructive to others.

After the Doctor regenerates, they’re 100% in couple mode, with Rose referring to the events of S1E2 as their “first date” and the Doctor happily assenting to this characterization (has Rose actually broken up with Mickey yet? Honestly can’t remember, but I don’t think Mickey knew it if she had). The Doctor and Rose have a deeply codependent relationship. We might attribute this to her dysfunctional relationship with Jackie and the Doctor’s recent PTSD. They latch onto each other like needy puppies, and this isn’t a criticism, because there are really people who fit these profiles, and they are not bad people, and it does make for interesting characters and good storytelling, but it’s by no means a healthy depiction of a relationship.

Consider, for instance, that the Doctor tries to send her away (no doubt he felt he was making a noble sacrifice, but he did this against her clear and repeatedly expressed wishes, and with the complicity of Pete). Rose ignores the Doctor’s clearly expressed wishes and comes back, which, fair enough I guess, but it all ends in tragedy anyway. So what does he do? HE BURNS UP AN ENTIRE SUN just so he can say goodbye. I mean, I’m sure he verified it was not an inhabited solar system, but seriously. In that goodbye chat, he specifically tells her that they cannot get across the barrier between universes because “the whole thing would fracture. Two universes would collapse.”

Does Rose accept the judgment of the person who is unquestionably the foremost person in either universe able to evaluate the risk of such an attempt? No she doesn’t. We learn in series 4 that even before the stars started going out, she was having Torchwood build a DIMENSION CANNON to P U N C H. A. H O L E. IN THE UNIVERSES!!! like presumably as many as it took for her to find the right one. Just so she could get back to him. AFTER HE MADE IT CLEAR THAT IS NOT WHAT HE WANTED. BECAUSE IT WOULD DESTROY THEM. This is portrayed as romantic rather than horrific. Seriously. And then he dumps his problematic clone on her and goes back to his own universe. SO ROMANTIC. Sorry, I try not to be rude about Rose’s relationship with the Doctor. I think it’s actually an interesting dynamic that makes sense in context, but it really bugs me that so many people view it unproblematically, and it bugs me even more that people don’t imagine both Rose and the Doctor growing out of it. Like, I can’t lie: I think that’s wacked and super unhealthy, in much the same way (though to a lesser degree) as the Twilight series and its fans are, except Doctor Who is still better-written and far more interesting.

That said, I’d be willing to read a well-written fix-it fic that depicts them growing out of their unhealthy codependent dynamic while staying together romantically. TBH I’d be more interested if it were Rose and Tentoo because then it would be canon-compliant, but I’m not too picky on that point. I AM picky about it not even remotely disrespecting the relationship the Doctor had with any other companion though. And it would have to have a whole “you were so obsessed with me that you were willing to destroy an unspecified number of universes, INCLUDING THE ONE YOUR FAMILY AND BEST FRIEND WERE IN, just to see me again for a brief period of time before this universe also collapsed WITH US IN IT and honey, that’s actually CREEPY AND GROSS even though I thought it was super sweet at the time, but in my defense the universe was already ending at that point anyway and you don’t have that excuse because in your case it was PREMEDITATED” conversation because otherwise I won’t believe they’ve actually grown as people. Also it’d be nice if it were funny more than angsty (but lbr you can’t write what I’m talking about without a fair amount of angst). So, y'know, if anyone has actually written that fic lmk.

Meanwhile, there’s MARTHA.

OK so I’m on record about how awesome Martha is. This is already getting long so I won’t belabor Martha’s total awesomeness as a character, but even though I got a bit tired of dysfunctional family relationships in New Who, it was novel to see them have any ongoing family relationships at all, and Martha’s was particularly rich, partly there were so many of them for her to interact with, thus revealing lots of different facets of her character. And despite her fractious relationship with them, she remained fiercely loyal, which was an interesting source of tension between her and the Doctor, and one that diverted attention away from the dental-drill painfulness of the unrequited love subplot.

It’s super gross that the writers made her hung up on the Doctor all the way through series 3. Not because it’s ridiculous for an intelligent, perceptive, professional young woman to be hung up on an emotionally unavailable man. No, that really happens to actual human beings (and again, possibly related to serious parental issues, so it’s not even without narrative justification). Handled with any sensitivity at all, it could have made for a lovely level of complexity. What really bugs me, and I’ve also written about this before, is how the Doctor treats her like GARBAGE, and this is barely addressed as a problem that he is responsible for. In the end Martha realises her mistake in sticking around for so long, but her attempts to call out his bad behavior in the past fell on deaf ears. Martha is the rebound girl but he acts like he doesn’t even know he’s doing it. Which, IDK, maybe he really doesn’t know? Like for all his 900+ years the Doctor has little previous actual relationship experience and also he’s super blindingly hung up on his high school-esque sweetheart Rose. And it’s not just in regards to Martha’s romantic feelings that he treats her poorly. He also dismisses her VERY VALID CONCERNS about her own safety and well-being when traveling in the past for the sake of his own whims. And he brushes off legitimate questions about how stuff works. Anyway. This is well-trodden ground. As is the fact that RTD later inexplicably fobs Martha off on MICKEY, the only other black companion in the series up to that point, despite having already paired Martha off with a cute, sweet doctor who seemed like a MUCH better fit, and there literally being no narrative reason for them to be a couple in that scene.

Donna! Well, as we all know, Donna is among the best-developed companions ever.

She didn’t start out that way though. She started off as a Deeply Problematic (read: disgustingly misogynistic) Stereotype who was never meant to be more than a one-off, but CT and DT got along so well that they brought the character back full-time, and so we got a lot of deconstruction, exploration, and development of that first impression. And I’ll forever be happy we did. But even in The Runaway Bride, she had moments of surprising depth and pathos. Deep down, Donna was always better than she seemed. The fact that she was the last person (other than her mother) to realize that fact is part of what makes her so compelling.

Her relationship to the Doctor is also the least problematic, because they’re both on the same page about being platonic bffs. To be fair, part of the reason he does make sure this is clear from the outset is because he has finally realized how he hurt Martha (NOT THAT HE EVER APOLOGIZED TO MARTHA FOR THAT–for a guy for whom “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry” was basically a second catch phrase, Ten actually sucks at apologising to the people close to him). Unlike Martha, the Doctor doesn’t overlook Donna or brush off her concerns. Unlike Rose, he is not codependent with her. Donna calls him on his BS, and he listens. She helps him to face his emotional vulnerability rather than running from/shutting out potentially scary personal relationships (like with River and Jenny). The Doctor helps Donna to see that she really is brilliant and important, and she grows to believe him.

That’s not to say that Donna’s character was handled perfectly. No, indeed. Even after her first story, we’re repeatedly subjected to jokes about her desperate need for and inability to get a man. Even the Doctor, who is otherwise kind to her, takes these jokes for granted and sometimes participates in them. At the end of series 4, we’re shown that the one person in the universe that Mr. Pansexuality Personified, JACK HARKNESS has no interest in flirting with is Donna Noble, the man-hungry middle-aged slightly overweight loud temp from Chiswick. And then, of course, the Doctor denies her agency and takes away her access to the memories of everything she saw, everything she did, everything she discovered about herself while traveling with him. Just so he wouldn’t have to see her die. It was selfish of him. She made her choice and he ignored it to spare HIMSELF pain. But, y'know, at least the Doctor cheated the lottery to make her rich as a wedding present to a very attractive, kind-looking, and clearly adoring man–right before he regenerated. So she did get a happy ending.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The “Evolution” of a Problematic Shipper

[I’ve been working on this lengthy post, which is about my early adventures in X-Men: Evolution fanfiction, for a very long time. So, here it is, friends. Please note a content warning for some discussion of abuse, mostly in fiction. Also, my individual recollections are my own, and extremely subjective; others might remember the fandom differently than I do.]

Quite a few years ago, I wrote about how X-Men: Evolution was “the first fandom in which I participated heavily: watching the show as it aired, obsessing with other fans about the stories and relationships within, and writing reams and reams of (mostly very bad) fic.” I still think that this is somewhat true; XME certainly inspired me to do all of those things more publicly and enthusiastically than I ever had before, especially where my One True Pairing was concerned.

For those who don’t know, X-Men: Evolution, which ran from 2000 to 2003, was essentially an animated High School AU of the X-Men comics in which our heroes lived and trained at the Xavier Institute but attended classes at their local high school. For the first couple of seasons, mutants weren’t public knowledge as they are in the comics or movies, so a few characters used their powers for the first time without understanding what was going on.

The second episode, “The X-Impulse,” introduced viewers to (this world’s version of) Kitty Pryde, a lonely, sheltered fifteen-year-old who was terrified of her newly awakened ability to walk through walls, and to Lance Alvers, a juvenile delinquent whose own powers caused him to make awkward faces and terrible puns (and also earthquakes, I guess). When they met, Lance seemed happy and excited to meet someone else with super-powers, but he quickly developed a plan to manipulate Kitty into helping him in his criminal shenanigans. He presented himself as helpful and supportive, gained her trust, and, when she refused him help him, became aggressive and violent toward her and her family. The episode ended with Kitty recruited by the X-Men and Lance joining the bad guys, and the two of them spent the rest of the season as enemies.

Watching this episode for the first time as a teenager, I knew that Lance’s behavior toward Kitty was wrong and abusive. And yet, there was something about their early interactions that captured my imagination. Maybe it was the fact that, whatever else might have happened, he was the first person to show her how to find confidence and joy in her powers. Maybe it was the hug that they shared, or his line, “Once you own it, nothing can own you,” or the possibility, thwarted though it might have been, that they could have formed an understanding despite very different backgrounds and attitudes. I liked forbidden romances, and I liked flipping the script to make unquestioned heroes seem villainous and villains seem sympathetic, and I liked when characters rebelled against controlling authority figures and communities, which is how I reimagined the X-Men when I first started writing about them. I’m not saying that I explored any of those ideas well, but they were what started me writing: at first in collaboration with a friend from summer camp, who still deserves a lot of the credit, and then on my own. I posted my solo stories on Fanfiction.net, where this fandom would enjoy some remarkable popularity that I’m not sure has ever transferred to any other platform.

I wrote about Lance infiltrating the X-Men (with psychic shields in place), and having to choose between his original mission and his romance with Kitty, whose own commitment to her team and its mission was starting to waver. I wrote about her trying to figure out her identity beyond her friends’ expectations of her, even as Lance tried to be a better and less destructive person. I wrote about Charles Xavier mind-controlling Kitty into dismissing Lance and falling back into unquestioning loyalty, giving way to several well-received sequels in which some of the characters tried to free themselves and each other from Xavier’s telepathic chokehold. I wrote without much direction or concern for established continuity and characterization, and assumed the whole time that the show would never explore what I saw as the unrecognized potential of my OTP. When canon actually went there, I was as surprised as anybody.

--

After Lance had spent the entire premiere of Season 2, “Growing Pains,” acting like a complete jerk to Kitty and her friends, his destructiveness endangered her life, and he saved her. They became romantically involved soon afterward, and he became noticeably less of a jerk toward her and slightly less of a jerk toward others. The series of fics that I was working on had decisively departed from continuity by this point, but I still incorporated elements of the season premiere into the installment that I was posting at the time. And my fellow Lance/Kitty shippers, believing that canon had vindicated us, were transported with joy.

If XME were popular today, I believe that there would be a lot more pushback against Lance/Kitty, in both good and bad ways. Even at the time, the pairing was not universally beloved. There were probably those who thought that its dysfunctional beginnings outweighed any potential for functionality or sweetness, and there were definitely those who thought that both characters would be better off with someone else. It’s tempting to rewrite history with claims that “in my day, we shipped and let ship,” and it’s true that yesterday’s shipping conflicts didn’t use all of the same weapons that today’s do, but the fandom was still full of snarky, self-important brats who, no matter which side of any given argument we were on, believed that only we understood these characters and this world.

I say “we,” because I was not exempt from these behaviors. I’ve sometimes thought that participation in this fandom brought out some of my worst habits. But a lot of positive things came out of it as well. It gave me the inspiration and confidence to write more prolifically than I ever had before (or maybe even since), and a chance to explore ideas that became deeply important to me: perhaps most importantly, I don’t think I’d written so extensively or publicly about the horrors of mind control. Mutual devotion to our show and its fandom, and mutual conviction that Lance and Kitty were meant to be, connected me with a number of friends with whom I started exchanging emails and IMs and LiveJournal comments, and I’ve kept in touch with a couple of them to this day. And even though I didn’t always respond constructively to attention and validation, XME fandom gave me what I think fandom has given a lot of creative young people: a wider audience for my writing, and a community who cared about the lives and feelings of cartoon characters as much as I did, and in many of the same ways. My experience in this fandom was as uneven and as flawed (dare one say… problematic?), and often as delightful, as the show that inspired it.

And, for me, it had all started with Lance and Kitty. As the show progressed, and for years after it ended, I continued to write more canon-compliant one-shot stories about them: missing scenes or predictions for the future. Their relationship was a given in more or less everything I wrote, whether or not they were the focus, and even when I’d fallen deeply into other fandoms, I still regarded it with nostalgic fondness.

--

I think that a lot of us have faced an uncomfortable tension between our social consciences and our nostalgia for the uncomplicated adoration with which we viewed our “problematic faves” as children. I can’t provide a one-size-fits-all solution for that conflict. I don’t know if one exists.

“Although I'm not going to say that I never thought that I'd be engaging with XME again in any way,” I blogged in late 2013, as my local cartoon-watching group began the first season, “I was somewhat surprised that I had any feelings about this show left, or anything else to say.” But I did, and I said a lot of it in short ficlets of less than 500 words, which - since I was in graduate school at the time - were usually all that my energy levels would allow.

At around the same time, I started reading fandom-related posts on Tumblr, including the ones that stated or implied that redemption arcs in fiction, and/or shipping characters with people who had mistreated them, were universally bad because they would increase the likelihood of real-life abuse. It’s not like I had never thought about that aspect of Lance and Kitty’s relationship (I’d addressed it more than once in the intervening time), but something about phrasing of those posts - or maybe something about my own mental state when I saw them - sent me into a spiral of self-doubt. I wondered I would have to publicly apologize for and cast aside my affection for a pairing and a narrative that had been so deeply formative for me. I wondered if my friends would consider me an abuse apologist if I didn’t, or even whether I might secretly be one.

One of the reasons why it took me a long time to write this retrospective is that I wanted to avoid too many lengthy tangents or blanket statements about critical consumption of media, the toxic elements of “anti-shipping,” and the relationship between fiction and reality. I do believe that such a relationship exists, but it’s much more complicated than “impure fiction is dangerous, especially if people might be enjoying it in ways that are not politically conscious or wholesome enough.” Anybody who reads my blog knows that I am intensely critical of purity culture, and I do not believe in being unkind to real people on behalf of fictional characters (and I say this as someone who used to do exactly that). Also, if you were going to ask, “So you’re saying you support [taboo and/or illegal act]?” please don’t. I am not saying that, and we are not having that conversation. Not all “problematic” stories are interchangeable or should be talked about in the same way, and all of the issues that surround them are bigger and more complex than any individual character or romantic arc.