#but i kept this post mostly to my PERSONAL theories around art and creativity rather than ethics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

there is a lot to say about the ethical problems and blandness of AI art but also just as someone who likes digital art because it’s low maintenance low cost to pursue, i think that it’s INCREDIBLY BORING to look at ai art because the creative process is lost

like people might gripe that digital art isn’t “real” art because of the difference in craft

but ultimately i think each individual artist shapes their workflow to suit their needs and some people are able to do a lot of design work using presets and filters and photo-bashing and generative tools in ways that are creative and using a process that takes thought and problem solving

and personally i like the process of high effort art in traditional mediums and that reflects in my digital drawings, i love painting to render texture and light to an image for example, while i do use brushes and other tools overall i think the actual act is soothing and fun

and i think the creative collaboration when working with someone else’s prompts (a process that can be immensely frustrating when one-sided) is also a valuable experience as people can ask questions and negotiate concepts you might not have thought of on your own. the immediacy of output with ai, the way it flattens composition to the most common plagiarised components, it’s fun as a what if or a starting point but it is a creatively incomplete endeavour specifically because the ai is communicating nothing and the person creating the prompt is almost entirely removed from the creative process. one sided intentionality without the meat of creation

ALSO for contrast i was thinking about the tradition of fractal art/fractal flames dating back to the 80s but more specifically being boosted in popularity alongside the world wide web thanks to one person’s algorithm in 1992. that guy now works in AI generation but back in the 90s he created an open source code that took mathematical iteration and translated it into graphics in common software applications that anyone could use. as a result i saw so many cool abstract almost mandala-like spacey images in the 2000s on deviantart and people are still making them today. it’s an artform that can only be successfully executed thanks to computers, it i complex in the process of execution but thanks to computers the process of creation is quick and seperate from human effort, the output is also very nice to look at.

Why do i like this form of generative computer art and not so called a.i? Because the algorithm for fractal art is pure mathematics translated into imagery, while generative a.i/neural networks datasets inherently require an input of other people’s work. a process that requires ethical consideration in ways that mathematical inputs do not. both use data to create images but what do they feed on? how are they applied? does their implementation say anything about their process or output?

because as far as i see it, technology is neutral and usage is where the good and bad emerge, the process of generative images is a marvel of technology and how we as people love to create. but the way that these tools synthesise what they are given is a process so seperate from the people inputing prompts i really feel like it’s people losing the most fun parts of art (emotion, communication, and participation) and receiving the worst results of commodification of art (plagiarism, formulaic content, aesthetic cowardice, narrow perspectives, exploitation)

#long post#repeating things i've said before#but i really do think a lot of people who simp for ai art#and act like this situation is people being bitter they aren't as efficient as a machine#are philosophical cowards#and i mean that sincerely i think it is a type of thinking that is so embarrassing#also once again why are ai held to a different standard than actual creative professionals#when it comes to copywrite and licensing and plagiarism?#that's a rhetorical question the answer is corporations do not care about you and they will replace paid work with free garbage every time#i don't think everyone who develops ai tools are evil i think it is a fascinating process#but i kept this post mostly to my PERSONAL theories around art and creativity rather than ethics#cause otherwise i would just end up ranting about the irresponsibility and lack of moderation/oversite in the tech world as a whole#and others are more qualified and informed on that topic than i#but everyone is qualified to talk about what they think about art so i can make this post lmao#sorry for rambling in the tags too i love to never shut up

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actually I think if writers and linguists are in the words fandom, that means artists and some physicists are in the light fandom, coders and mathematicians are in the numbers fandom, and textile designers and engineers are in the Squares fandom, etc etc etc

So art (regardless of if they're making books, paintings, video games, or a sweater) all benefits in some way from STEM fields. Most people are probably less frustrated that they're in Science™ classes than the fact that they probably want to stick to their Fandom. College courses that have overlapping fields should pay less attention to "whatever art/STEM class they can pass!" and start giving people classes that they would benefit from passing to begin with

Like, honestly, I'm still scandalized that I kept getting recommendations to take the "easiest science credit we offer" despite having 0 interest in repeating the basics I understood already in highschool. If someone told me to join a class on linguistics, rather than generic ~social science credit~ I would have jumped at the chance. Hell, there's dozens of ways to have overlap. I see it all the time with humanities. History courses about art. Art courses coupled with poetry. Why not the science of photography for art AND science students? The physics of cashmere. Math as a language vs code as a language vs English as a language.

Give students more options that don't artificially create a dividing line between the two groups of fields. Even if the above weren't true, this still acts as if I can't understand what a physics major is saying better than someone without any degree training because I was at least trained in Academia Speak. Students lack confidence in the "other" field because no one bothers to give them any in the first place

Anyway this post is just to say that I thought I was A Bad Artist because elementary school art didn't include enough written/scientific explanations for the exercises we were doing. You can create a hundred shaded cubes, if you don't know why you're even doing it the whole exercise is pointless. The idea that you just ~understand~ art through seeing it with your eyeballs centers primarily visual learners (which- ydy! Visual learning itself is rad) and that's why people assume if they can't do it automatically on the first try they can't at all. My ability to reproduce images from complete memory is utterly useless if I don't know how to reproduce images unless it's a cube- without the theory, I don't know that's how sunshine works because I have to be told the big picture stuff first.

On the other hand, I could Words at the first try because that's how I learn about stuff and things, and everything else has to be translated for my brain to get it. Woodshop had the same problem- they'd do a bunch of things and I'd be like "wtf" but if they just said I needed to screw until it was flush without me asking, I wouldn't have needed to ask, and I would just Do the thing. But since I could actually use my personal skills (creativity, memory, zest for life) with writing because I understood it, I have much higher grades in English. I even got praised for it more despite having equal amounts of ADHD at all times. Because the class is accessible to my learning style. If it wasn't accessible, then I wouldn't get compliments, despite having the same amount of so "innate talent" (practiced skills available) either way.

So many people are walking around thinking that they suck at English because they might understand it better through typography or audiobooks and the institution pits us against each other based on what we're naturally inclined towards. Institutions act the only way you can learn about English is through books and like the only way you learn art is through your eyeballs. I'm not "better" than someone that picked up reading picture books when they were older because they didn't have the right glasses to read, and I'm also not better than someone who finds doodling helpful and never got credit for their journal entries because they weren't words even if they were thinking about the text critically.

And like. This applies to fields. No one should be forced to write a book. Not only does that make for dense, incomprehensible texts but . . . remind me again who's reading them? Other STEM people mostly. Why would you do that. You incentivized a group of people to be good at science and nothing else, present them no methods to learn English skills they understand, no wonder they're so bad at it.

That's all on top of their professors not knowing how English works so they apply science logic to language while they also dismiss the field because they're never taught the benefits of reading in any meaningful sense- and even their scientific thinking shows extreme failures of thought because they don't understand even the most rudimentary English concepts.

And some things they think are just flat out incorrect. They believe humanities majors make less (not always) because there's less skill (never) or less capitalist value (blatantly false- look marketing). They think that because they're a STEM they can more accurately assess this information than, say, someone qualified, like a STEM in language related fields- saying things like Latin/English/Chinese is the only language worth knowing, acting like introduction clarity is less important than your graphs, thinking that their work is not conditional on the people that provide access to the materials in the first place.

Holy shit this post is long. Anyway academics should stop judging other people in their fandom, and schools and colleges should make it easier to learn in other fields than the auto fill assumption that because you're good with learning via words, you're going to go into English, and if you're good at learning through seeing things, you're going to go into art.

#personal#academia#elitism#activism#education#accessibility#this also helps people like me that learn from examples#overlap courses often have concrete examples of things they're focusing on#to develop the theory#neurodivergence#adhd#ableism#disability

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Remus Sanders

So the new video came out and I have a lot of thoughts on a lot of different things, but for this post, let’s talk about our new resident trash man, Remus Sanders, aka The Duke, aka the Dark Side of Creativity.

Remus’s Role (who or what is he?)

First off, Remus’s ‘Side Title’ as it were is definitely Creativity. He is not simply “Intrusive Thoughts.” That is not his function, intrusive thoughts are a result of his function, an area of thinking that he is responsible for. Like Roman, he embodies Creativity and the Imagination, but unlike Roman, he deals almost exclusively in ‘dirty,’ mature, dark, or disturbing ideas. Sure, the video was about intrusive thoughts specifically, but that’s not all that Remus does. He said himself twice, once in song and once in regular speaking, that he wants Thomas to explore more mature themes in his videos and to be more “realistic” with his creations. So while the other “dark sides” like Deceit and Anxiety (maybe Paranoia?) have different functions than the “light sides,” Remus and Roman are two sides that embody the same trait: Creativity.

As Thomas said, the Duke and the Prince literally wear black and white, because his relationship with his imagination while he was growing up led to Roman encompassing the “good” parts and Remus the “bad” parts. Both ‘sides’ of creativity are important over all, but Thomas specifically gave Roman, the light, the positive sunshine rainbow unicorn side, more import than the dark, the twisted macabre disturbing side. Hence Roman is a Prince, while Remus is merely a Duke, a lesser rank of nobility.

Remus’s Goals (so what does he want?)

Like Roman, Remus wants Thomas to create things, things that he can be proud of. And more SPECIFICALLY, he wants Thomas to be remembered, to have a legacy. Roman, you will note, wants this too. All sides, after all, want what they believe is best for Thomas, but they all have different views of what that looks like AND of how to get it. And Remus believes that the darker sides of creativity that he encompasses are the way for Thomas to get that notoriety he craves. Just look at the way Remus talks (or sings) about himself in relationship to Thomas’s content:

“If you really wanna challenge your viewership, then you need to stop limiting me.”

“If you want the spectrum A-Z you’ll need a little help from me.”

(in reference to Thomas only wanting bright and happy things in his content) ”Hey Prude, your art is Bad.”

“What will our legacy be? Will you even have one? How about this: you get buck naked on camera and self immolate to Taylor Swift’s Shake it Off! That’ll leave an impression!”

Remus wants what ever creator/performer wants: he wants to be remembered. But unlike Roman, he holds no reservations about how they get there.

But Remus ALSO a rather chaotic force in general, and you get the feeling that he really just wants to have fun...unfortunately, what’s fun for him is not very fun for most people, Thomas included. Remus is more like the way many of us characterized Deceit at his first introduction: likely to be cruel for no reason. Because it’s fun! Right?!

Roman vs. Remus...why?

I have a headcanon that Patton (or Patton’s influence) is largely responsible for the development of Remus and Roman as separate entities, actually. During their conversation about Just Like Heaven, Patton mentioned that a happy ending “makes good cinema.” And...no, it doesn’t. Objectively, good cinema, good ART is not dependent on whether or not it is happy. Now, whether or not it is happy is certainly a valid indicator of whether or not YOU as an individual like it. But not it’s objective quality. And that’s what has happened with Roman and Remus, anything that Thomas’s Moral Code (again, Patton himself or his general influence) deemed as “bad” or “wrong” got shoved into Remus, while Roman kept all the good parts for himself.

When you look at it that way, it’s no wonder that Remus spends so much of his time sending intrusive thought’s Thomas’s way. (Yes, intrusive thoughts are fairly common, but not everyone has them, and not always to the severity that Character Thomas does) That’s basically his ONLY creative outlet, as everything else has been given to Roman. And why it makes sense that he is desperate to be more involved in Thomas’s creative process. Intrusive thoughts are all fine and well, but if Thomas isn’t ACTING on them, then Remus is effectively not being listened to, which as we all know is every single side’s greatest source of frustration.

His Logo (this is a pure guess based on my own theories and observation, but it’s fun to think about.)

It’s been theorized before that the “dark sides” have something animal themed in their clothing and/or appearances. Deceit’s is obvious the two headed snake, and Virgil’s is largely thought to be a raccoon, and if we look closely, Remus seems to fit this theory. His animal is some sort of tentacled sea creature, as evidenced by the thumbnail of the video, his green coloring, and the belt buckle he wears. Some have suggested a squid or octopus, but this IS Creativity we’re talking about here...it could be Something Else. Something a little more...creative.

“Whoa, you guys are acting fishier than the Kraken’s crack.” -Roman, timestamp 3:43.

I propose that his ‘animal’ is a Kraken, a giant sea monster known for causing great destruction, killing sailors and dragging ships down into the depths of the sea. Sort of like how our Dear Old Duke seems to take pleasure in being destructive towards both himself and others and dragging Thomas’s thoughts down into the depths of depravity? Huh? Maybe? Imagine a logo similar to Roman’s, but instead of an idyllic castle, it’s a giant sea monster. Perhaps reaching it’s tentacles around a ship? Or perhaps looking a little sleeker and going for something like the Hydra logo in Marvel? I dunno, it’s fun to think about!

The Rainbow Theory (no, I’m never gonna let this one go)

Remus’s existence, and more specifically, his color palate, only reinforce the Rainbow Theory as being canon. Thomas is Full Rainbow all the time, and each of his sides encompasses one color on that spectrum. You have Red (Roman), Orange (a yet to be discovered “dark side”), Yellow (Deceit), Green (Remus), Blue (Patton), Indigo (Logan), and Violet (Virgil).

One of the reasons I really like the rainbow theory is that it allows for a sense of balance between Thomas and his sides. I like to imagine it like this: There are three “light” or “good” sides, (Roman, Logan, and Patton) and three “dark” or “bad” sides (Deceit, the Duke/Remus, and an unnamed, Orange party). I use quotes on these labels because arguably, any trait could be used for good or for bad, and no side embodies this more than Virgil. Violet, the odd little shadowling out. The side that is now canonically CONFIRMED to have once been considered one of “the Others,” but who now has an equal seat at the discussion table. The side, if you will, that is the tipping point on the scale between whether or not Thomas is a “good person?” Ah, but that’s a theory for another post ;)

If you combine the rainbow theory with a color wheel, Remus’s appearance also all but confirms some theories that we’ve had about “dark” sides in the past: they are opposites to/extensions of/foils for a corresponding “light” side. It’s no secret who Remus’s corresponding side is, both he AND Roman are literally both creativity. And what is Red’s complimentary color on the color wheel?

Green.

While it’s harder to tell who Deceit’s foil is, since the blue/indigo and the yellow/orange parts of most color wheels you look at are more blurred, but I’m leaning towards Logan, the darker blue, the indigo, being the foil to Deceit’s Yellow, and Patton’s lighter blue being complimentary with the Orange Side yet to be revealed, since the light blue is closer to the green and the orange is closer to the red.

This also solidifies the idea that I have that Virgil himself has no foil. I see some people suggest he could be Logan’s foil, but I honestly think that Logan’s foil is either Deceit or Mr. Orange, and the Patton’s is whoever Logan’s isn’t. Virgil’s trait doesn’t necessarily have a perfect foil...and purple in particular has no opposite color that isn’t already sort of taken by one of the other three “light” colors. But I digress, this post is about Remus, not Virgil. I just like talking about the rainbow theory, I think it’s neat!

Other, smaller observations (mostly just fun things I noticed/liked about his character)

As much as they are opposites in ways, Remus shares many mannerisms with Roman, from his expressions to his vocal ticks to his gestures.

Literally less than a minute after he first appeared on screen, he broke out into an entire Disney Villain style musical number. (no really, he appeared at 6:00 and started singing at 6:53)

I sort of mentioned this earlier, but he is not only responsible for the darker parts of imagination, but also clearly things like childish potty humor and sexual innuendo. For THOMAS, this is a “bad” thing banished to it’s own separate side, but for some people, that kind of humor doesn’t cross the line. Joan, for instance, has both a raunchier sense of humor and darker sense of humor at times than Thomas, as holding up a disembodied corpse prop’s middle finger is, yeah, TOTALLY something they would do without Remus’s influence.

He cannot be insulted through traditional means, as he takes them as compliments. It is only through him being discredited/weakened by Logan’s words that we see him having any sort of negative reaction to the others.

Again, a point to get more into detail with another post, but he was particularly interested in beating down Virgil specifically, and in ways that seemed less relevant to what was going on like his taunts to the others. Just like with Deceit in the courtroom, he clearly knows Virgil well enough to get under his skin, and he relishes doing so.

The trash boi does not sit still, if he’s not engaged by what’s happening, he’ll find some other thing to occupy himself with, such as picking his nose or eating deodorant.

Like Deceit before him, he gets huffy when he doesn’t have his way, and then does his best to just be a general inconvenience (read also: a dick) to Thomas if he can’t be actually listened to.

That’s all for now! Thanks for reading <3

#sanders sides#sanders sides theories#ts theories#fanders#thomas sanders#remus sanders#ts remus#dealing with intrusive thoughts#long post#longpost#virgil sanders#roman sanders#patton sanders#logan sanders#deceit sanders#the rainbow theory#ts spoilers

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Eddsworld miscellaneous hcs

ok there's probably like 100 of these already or something, but I thought I'd add mine anyway, because hey, it's fun and I'll probably change or add a few later. (Also this ended up waaaaaaaay longer then i meant it to be wh o ops so uh be warned its pretty damn long-)

Tom:

Shortest! (i know it's normally either edd or tord, but after seeing saloonatics, I just couldn't resist the idea of the grumpiest one being the smallest. Cute right?)

Relatively strong arms, more fat around his stomach and torso then his legs.

Occasionally works gigs at local clubs and stuff for money.

Doesn't have much social media aside from Facebook so he can occasionally stalk his old college mates.

He actually likes sports like football and tennis. (His favourite sport is seeing how many bars he can hit up in one nigh-//shot//)

His hair smells like pineapple! (And the rest of him like booze-)

He's up for pretty much anything if he's drunk enough to have fun and not remember enough to regret it

But not bowling.

N e ve r bo wl ing

He's still got a scar on his left arm from The End. :( But Matt and Edd helped him to fix it up, so it's all good!

He's actually a pretty chill and sensible guy, and despite being snarky and sarcastic whenever he can, he genuinely cares about his relationships with people, scared that one day they'll get bored of him and cast him aside. He's really just a goofball with big city dreams of becoming a rockstar.

Spends like two hours in the shower crying and listening to MCR

His favourite show is Bad Education. It's good for when he needs cheering up.

He likes snacks and foods that are crunch, and salty, spicy, and sometimes savoury. So Crisps, Pringles, Doritos, chex mix etc.

Edd:

Second shortest/third tallest

Kinda chubby tbh but he's the BEST at hugs.

His forearm game is actually pretty strong because of all the time he spends making art to pay for their bills (because hey, someone's gotta do it amirite). You don't wanna head into an arm-wrestling contest with this guy.

Makes money by selling his art and also taste-testing all the latest cola products! (Just...not the diet ones).

Aside from a devianart, redbubble and maybe even a tumblr for art commissions, he doesn't really care about social media. Or regular media. Politics who?

His favourite sport? Seeing how many cans of cola he can get through on an especially difficult project. (Cricket always looked kind of fun though)

Smells like cola and not taking a shower in days because he HAS to get the lineart perfect and edd are you ok when was the last time you slept- (jokes aside, i can see him smelling like graphite and paints and sharpies from his art supplies).

Can pull the perfect poker face like damn son having a baby face sure comes in handy when lying to your roomate about why there's broken guitar strings hanging out of Ringo's mouth again

Has a scar on the inside of his eyelid from the time Tom 'accidently' poked him in the eye with a pencil (...may or may not be based off personal experience)

Edd is pretty friendly and open with people, he likes getting to know them and joking around. He's the Ultimate Punmaster ™, and loves nothing more to poke fun. He sees the world through the eyes of a cartoonist, and will never miss a comedic opportunity.

Be warned! He's actually fairly smart, and can read people well, knowing just how to really get under someone's skin. It's a good thing he can't be bothered with any of that though.

Gets his best ideas either in the tub or when hes just about to sleep. Because of that, he keeps a water-proof and regular notebook. Nearly had a heart-attack countless times because he accidently swapped them around.

Despite his complaints about absurd plot conveniences, he actually likes Doctor Wh- i mean "Proffesor Why", there's just something about the concept of time travel...he also likes cartoons! Like, a lot. He'll watch most anything and everything if it's animated and the writing is decent.

Likes anything sour, sweet, and chewy! So Jelly Babies, Wine gums, Sour patch kids, that kind of thing

Tord:

(Most of these are heavily based upon his life as Red Leader so sorry if you were looking for more domestic Tord. Maybe I'll do seperate hcs for that one day)

Second tallest! Quite a bit taller then Tom, a bit taller then Edd, just about average height, if a bit taller. He's closer to Matt in height then Edd.

He's actually quite well-built! You wouldn't think it because of the baggy hoodie he wears but he's got pretty good muscle, and his endurance and strength is well above the others. This mostly comes from the logic that he's been training and leading the Red Army, so it just makes sense to me that he'd resemble a soldier physically, yknow? AU-wise, or before he started the whole world domination thing, he'd be a little more scrawny, but he could still kick everyone's ass (he probably tried copying numerous anime battle stances lol-)

He's pretty well off, it turns out you can get quite rich by adopting some uh...rather unconventional means of money-making. Of course you could always say he just sold his inventions.

Does having your own private network of underground intelligence-gathering units count as social media? No? Nevermind.(He has a hentaihaven account-)

He likes dodgeball, archery, and you guessed it, arcade shooter games. Anything where he can point and hit something basically.

He smells like gunpowder, dirt, oil from machine maintenance and the cold? Like if the cold had a smell, he would have that smell, does that make sense? He also probably smells like Old Spice because idfk it just reminds me of him ok.

He doesn't exactly get out to socialise much, be prefers to stay at his desk, or curled up next to the fire with a mug of hot cider when he wants to relax. Sometimes Paul and Pat will drag him outside when they think he needs a breath of fresh air, and they'll go visit the nearest marketplace for food and other supplies. He likes strategic games like Chess or Draughts, and it's a good way to show off and get practice at the same time.

Scar-wise, he probably has quite a few from his fights. Post-the end, I'm not sure what would happen to him, since I've seen people go in a lot of different directions. I DO think he'd replace him arm with the robotic one, since that seemed too heavily implied to not happen. Regarding his face, I think the burns and stuff would probably heal over time, and depending on the technology in the future, he'd either still have some heavy scarring, or maybe he'd develop some kind of treatment so that it restores him to almost fully healed. He could always go the cyborg route and end up half-man half-machine like we see with future Matt and Tom.

(About the patch on his face, I have a theory about how he he aquired that scar/injury. See, I don't think Tord founded Red Army by himself, no. I think he was introduced to it by Paul (who we see in the same classroom as them in Poweredd) who was kept back a few years cause....uh...yknow- Anyway I have a theory that Tord eventually climbed the ranks until he became second-in-command, and he then murdered Red Leader and took his title. Their fight is where he got that injury. It's not really canon-supported much, but I find it an interesting concept!)

You've probably guessed, but I kind of disgree with Tord's portrayal sometimes. I think I prefer the darker, meaner side to him. I wouldn't say he's (completely) evil, but I'm not really one for the whole "self-hating, regretful angsty Tord who just wants some love and support" and stuff. I mean, it's cute with ships amd fluff, amd ideally he does make amends and rejoin the group, but I just like the thought that he's genuinely not a nice guy yknow? Like, he's actually done some fucked up stuff, and The End is probably just one case. (Of course this is all opinion based so feel free to disagree if u wanna wheeze-)

Has the WORST sleeping schedule. Has been known to fall asleep in the bath/shower.

He prefers movies to shows. His favourite is the Kingsman series (he can relate on many different levels).

Likes bittersweet things, (just like his personality amirite-). So cake with coffee, or tarts, liquorice, hard candy, that kind of thing.

Matt:

(My favourite-)

He tol. Tallest of them all!

Someone once described him as "borderline twink" and tbh i agree. I feel like he'd have a slightly feminine figure (which is perfectly normal!) and he both rocks it, and knows he does.

He works at a nail salon every now and again, his self-confidence and bubbliness makes him get along well with customers. (Also Matt would definitely wear nail polish ok dont even try to convince me otherwise. Actually speaking of,)

He has EVERY kind of social media possible. Instagram, twitter, facebook, tumblr, facebook, snapchat, you name it! He's especially prominent on instagram. He likes to keep an ~aesthetic~

He likes gymnastics and dance, activities like that. Anything which puts him in a creative spotlight. He'd probably take up acting classes, and then insist on only being given monologues.

He'd probably have quite a pleasant and nature-y smell? Like uhh citrus-y, pine tree, a hint of flowers, that kind of thing. Although he'd DEFINITELY slap on way too much cologne on a date or something and end up smelling like he just emptied out a bottle of febreeze.

He'd probably go out quite a lot! I can see Matt being a social butterfly, his friendliness and general likeability probably mean that he's got a few friends and stuff around. I can also see him as the kind of person who'd enjoy taking walks in the park, sitting below a tree, that kind of thing. He probably runs a self-love session (that works a little TOO well). He wants to get out there and show off his beautiful face, so it doesn't take a lot to drag him outside (provided you keep a mirror on you, that is).

He doesn't really have any physical scars. I mean, i do hc him with freckles, but they don't count so. he has a mental scar. After he hit himself with the memory eraser gun, he completely erased his memories. It took a while for him to settle onto the personality he has now. His face was the one thing that he knew for certain held a sense of familiarity and stability, so that's partly why his narcissism boomed so much. He sometimes gets random flashbacks of being a zombeh leader, being less of a nicer person, and it can be quite unnerving for him. He also has other memory issues, which is why he can forget things so easily, and comes across as an idiot most of the time.

He can be quite oblivious, but I dont think hes a total idiot. He can read people fairly well, and is emotionally intelligent. He says stupid things sometimes despite knowing they'll get a reaction, just because he wants to, and thinks that life should be as fun and full of joy as possible. He's too trusting, and wants to see the good in everyone. At the end of the day, if you disrespect him (and his face), you'll see that he can be more then just the nice guy.

LUSH!! Matt is HERE for all those lush products. I'm talking bath bombs, lip scrubs, shower jellies, all that good stuff! And ofc he has like 100+ products for his hair and skincare routine, because let's face it, it's Matt. I also like to think he owns a bunch of bath toys and rubber duckies, and like the kid at heart he is, he'll sit in a bubble bath playing with them, and re-enacting all of their adventures.

He mostly prefers youtube videos over TV, so you bet he's subscribed to all the beauty gurus, vloggers, people like that. He does think children's cartoons are nice to watch though, so every once in a while he'll force Tom and Edd to sit with him and watch the latest season of My little pony.

He likes anything sweet and fun to look at! Especially if it's trending, so he can post pictures of himself eating/drinking it. So if there's another rolled ice cream/new starbucks-ccino/unicorn themed food item floating about, he'll probably be trying it.

(Ah man this turned out way longer then i thought. It went from simple headcanons to like full blown theories whoops- maybe i should make seperate posts if its too difficult to read? Anyway let me know what you think nonetheless!)

#eddsworld#ew matt#ew tom#ew tord#ew edd#eddsworld matt#eddsworld edd#eddsworld tom#eddsworld tord#ew hcs#headcanons#eddsworld headcanon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long Before MRIs, an Artist-Scientist Revealed the Inner Workings of the Brain

Self-portrait of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, taken by Cajal in his laboratory in Valencia when he was in his early thirties, c. 1885. Courtesy of Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Calyces of Held in the nucleus of the trapezoid body, 1934. Courtesy of Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

A century ago, alone in a cluttered private laboratory at his home in Madrid, Santiago Ramón y Cajal was exploring a new world. Its exotic trees and ferns sported branches and roots that intertwined in dense lattices, while strange, one-eyed creatures wrapped filamentous tentacles around each other. Although the strangeness of this landscape surpassed even the science fiction books Cajal favored, it was no fantasy. Through the lens of his microscope, he was looking at the world of the brain—the complex circuits of nerve cells, called neurons, that give rise to our senses, our emotions, and perhaps even to consciousness itself.

Cajal painstakingly mapped this “neuronal jungle” in exquisitely detailed drawings, charting the features of different types of brain cells, their stages of growth, and how they are organized. His hands became “precision instruments,” he once said, producing “strange drawings, with details that measure thousandths of a millimeter…[that] reveal the mysterious worlds of the architecture of the brain.”

Now, American viewers are getting a chance to see Cajal’s drawings for the first time. An exhibition titled “The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal” is currently on view at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery; it will move to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in April. The show, which features some 80 drawings—most of which have never been seen outside Spain—illuminates Cajal’s fantastic voyage into the brain. Layers of interconnected cells, labeled with arrows and letters, demonstrate how sights and sounds are conveyed by nerve impulses from the outer cells of the eye and ear to cells deep inside the cerebral cortex. The complexity and delicacy of the drawings are simultaneously amazing and uncanny, observed Roberta Smith in the New York Times: “It’s not often that you look at an exhibition with the help of the very apparatus that is its subject.”

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Glial cells of the mouse spinal cord, 1899. Courtesy of Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

“The Beautiful Brain” dramatically reveals the twin aspects of Cajal’s genius: the scientific brilliance that earned him a Nobel Prize and recognition as the father of modern neuroscience, and his unique artistic gifts—without which his monumental discoveries might have gone unnoticed.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was born in 1852 in Petilla de Aragón, a small farming village in northeastern Spain. Growing up, Cajal had a passion for drawing and dreamed of becoming an artist. “I had an irresistible mania for scribbling on paper,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Translating my dreams onto paper, with my pencil as a magic wand, I constructed a world according to my own fancy.”

His father, the local doctor, considered art to be frivolous entertainment and fiercely opposed his son’s professional aspirations. Eventually, he persuaded the boy to assist him in a human anatomy class he was teaching at the medical school in Zaragoza. Cajal found that he enjoyed studying the human body and that he could put his exceptional drawing skills to good use in the process. He enrolled in medical school in Zaragoza and graduated in 1873, at age 21, with the intention of devoting his career to histology—the microscopic examination of body tissues.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Injured Purkinje neurons of the cerebellum, 1914. Courtesy of Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

By the 1880s, although the tissues of most human organs had been studied in detail, the brain remained terra incognita. Even under the day’s most powerful microscopes, the mass of grey and white matter appeared as an undifferentiated blob composed of billions of indistinguishable cells. “The brain was the Holy Grail,” Benjamin Ehrlich, Cajal’s biographer, told Artsy. “Cajal and other scientists of the day believed that studying the anatomy of the brain would reveal the secrets of the mind. That’s what motivated him. When he was looking through the microscope, he was inside the world of the brain, trying to figure out how it worked.”

A turning point in Cajal’s quest came in 1887, when he saw a microscope slide of nervous tissue that had been stained using a new method developed by Italian pathologist Camillo Golgi. Golgi-staining allowed individual brain cells to be seen for the first time. Using the technique, Cajal could finally peer through the dense neuronal forest to see that it was composed of individual trees—neurons, with branching dendrites, where signals enter the cell; a cell body, where the signals are processed; and a root-like axon, where impulses are transmitted to the dendrites of neighboring cells, enabling them to talk to each other. No one had observed or described individual brain cells before, and Cajal’s findings were not immediately accepted. What became known as his “Neuron Doctrine” ran counter to the agreed-upon theory that the brain was structured as a continuous network rather than a series of separate cells.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Tumor cells of the covering membranes of the brain, 1890. Courtesy of Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, A cut nerve outside the spinal cord, 1913. Courtesy of Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

Inspired by what he saw, Cajal worked “with a fury,” typically spending 15 hours a day staring into the microscope and recording his observations. Over the course of five decades, he amassed nearly 3,000 drawings. He drew freehand in pencil, later going over the sketches in India ink and washes. He seldom made mistakes; in the drawings at the Grey, whited-out lines and corrections are rare.

Even more than the magical Golgi stain, it was Cajal’s trained eye that made this monumental achievement possible. “Golgi and many other scientists in Europe were looking at the same tissue, with the same stain, in the same way, but only Cajal was able to see structure inside of that stained tissue,” said Carl Schoonover, a neuroscientist at Columbia University. “He was able to see and analyze these extremely difficult-to-see shapes, then communicate his findings through these beautiful drawings.”

For the discovery of the neuron, the basic building block of the brain, Cajal would eventually share the Nobel Prize in Medicine with Golgi in 1906. “Like Einstein in physics, Cajal defined the parameters of modern neuroscience,” Schoonover said. “The specific cellular features of the neurons and how they’re arranged, which he drew so beautifully, is monumental.”

Argus, . Salvador Dalí Russell Collection

Cajal followed the path of a scientist, not an artist. But his drawings—reproduced more widely after he won the Nobel Prize—soon attracted the attention of the artistic avant-garde. Consciously or not, forms resembling the dendrites and axons of neurons began to be reflected in the automatic drawings of the French Surrealists André Masson and Yves Tanguy.

Spanish Surrealists Salvador Dalí, Federico García Lorca, and Luis Buñuel encountered Cajal and his work in the mid-1920s, while university students at the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid. Cajal, by then at the height of his career and a venerated figure in Spain, was president of the board for the extension of studies and scientific research, which funded students at the Residencia. He’d helped strengthen a curriculum of interdisciplinary studies there, which exposed scientists to art and artists to science. Buñuel, who had a fascination with entomology, actually worked briefly in the lab of naturalist Ignacio Bolívar. There, he studied bugs’ eyes under a microscope. (It’s unclear whether this experience influenced the famous scene of a razor slicing an eye in his iconic 1929 film Un Chien Andalou.)

Elephant Spatiaux , 1965. Salvador Dalí Off the Wall Gallery

Dessin Automatique (Automatic Drawing), 1927. Yves Tanguy DICKINSON

Obsessed by the desire to depict the inner truths of the human psyche, the Spanish Surrealists formed a natural kinship with Cajal. Although none of the young artists ever met the respected scientist, dendrites and axons were soon sprouting from human bodies and elephants in Dalí’s paintings. Lorca often paired his poems with his own drawings of filamentous forms closely resembling Cajalian imagery, including the numbers, letters, and arrows common in his histological drawings.

Although he possessed a rich imagination, reading science fiction and even writing two sci-fi novels, Cajal was generally conservative in his aesthetic tastes. He was no fan of modern art, disparaging it as “a contradictory jumble of schools that have christened themselves with the pompous names of avant-garde, Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Post-Impressionism, etc.” Nor did he support the Surrealists’ interest in Freudian dream interpretation. Regarding Freud as a scientific heretic, and believing that dreams had a simple, anatomical explanation, Cajal kept a dream journal throughout the last 16 years of his life, explicitly to prove Freud wrong. “I attend a diplomatic soirée and as I am leaving my pants fall down. Is it desire?” he sarcastically noted in one entry.

Le génie de l'espèce, 1942. André Masson Isselbacher Gallery

Le Pas - série des trophées érotiques, 1962. André Masson Le Coin des Arts

Beyond his anatomical drawings, Cajal’s personal creative life centered mostly on a lifelong passion for photography. The process of developing film closely resembled the process of staining tissue, and the ability of the camera to precisely capture reality was more appealing to Cajal than the abstraction of modern art. He taught himself how to make daguerreotypes as a teenager; later, he pioneered and perfected color photography techniques and even wrote a monograph on the subject in the early 1900s. The result was a prodigious archive of photographs, some of which are on display alongside his drawings in “The Beautiful Brain.”

And these wonders of Cajal’s vision are not lost on artists today. Caitlin Berrigan—a professor of emerging media at NYU who is collaborating with neuroscientists on a project involving three-dimensional MRI imaging—was particularly struck by the architecture of neurons in Cajal’s drawings. “The illustrations speak not only about that magical web of interconnectivity that we have within ourselves,” she remarked, “but remind us how interconnected we are with the world around us.”

For artist Teresita Fernández, whose installations and sculptures are inspired by nature’s marvels, Cajal’s work is a reminder that science and art are not that different. “Every artwork is an experiment,” she said. “You’re looking for something that doesn’t have a form yet, that you don’t understand, a mystery. And you try to find a new truth, something you didn’t know before. That’s what Cajal did. That’s where the conversations of art and science are parallel.”

from Artsy News

0 notes

Text

Small Circles: The Theory of Mastery in the Art of Learning and Investing

One of the best books on the art of learning I’ve read is, well, The Art of Learning by Josh Waitzkin.

Josh is a champion in two distinct sports – chess and martial arts. He is an eight-time US national chess champion, thirteen-time Tai Chi Chuan push hands national champion, and two-time Tai Chi Chuan push hands world champion.

In his book, Josh recounts his experiences and shares his insights and approaches on how you can learn and excel in your own life’s passion, using examples from his personal life. Through stories of martial arts wars and tense chess face-offs, Josh reveals the inner workings of his everyday methods, cultivating the most powerful techniques in any field, and mastering the psychology of peak performance.

One of my favourite chapters from Josh’s book is titled – Making Smaller Circles – which stresses on the fact that it’s rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the top, but rather a profound mastery of what may well be a basic skillset.

Josh starts this chapter with the story of the protagonist in Robert Pirsig’s book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. This man is Phaedrus, a teacher, who in this particular scene is reaching out to his student who is all jammed up when given the assignment to write a five-hundred-word story about her town, Bozeman.

Here is that scene straight from Pirsig’s book –

…a girl with strong-lensed glasses, wanted to write a five-hundred-word essay about the United States. He … suggested without disparagement that she narrow it down to just Bozeman.

When the paper came due she didn’t have it and was quite upset. She had tried and tried but she just couldn’t think of anything to say. He had already discussed her with her previous instructors and they’d confirmed his impressions of her. She was very serious, disciplined and hardworking, but extremely dull. Not a spark of creativity in her anywhere. Her eyes, behind the thick-lensed glasses, were the eyes of a drudge. She wasn’t bluffing him, she really couldn’t think of anything to say, and was upset by her inability to do as she was told.

It just stumped him. Now he couldn’t think of anything to say. A silence occurred, and then a peculiar answer: “Narrow it down to the main street of Bozeman.” It was a stroke of insight.

She nodded dutifully and went out. But just before her next class she came back in real distress, tears this time, distress that had obviously been there for a long time. She still couldn’t think of anything to say, and couldn’t understand why, if she couldn’t think of anything about all of Bozeman, she should be able to think of something about just one street.

He was furious. “You’re not looking!” he said. A memory came back of his own dismissal from the University for having too much to say. For every fact there is an infinity of hypotheses. The more you look the more you see. She really wasn’t looking and yet somehow didn’t understand this.

He told her angrily, “Narrow it down to the front of one building on the main street of Bozeman. The Opera House. Start with the upper left-hand brick.”

Her eyes, behind the thick-lensed glasses, opened wide.

She came in the next class with a puzzled look and handed him a five-thousand-word essay on the front of the Opera House on the main street of Bozeman, Montana.

“I sat in the hamburger stand across the street,” she said, “and started writing about the first brick, and the second brick, and then by the third brick it all started to come and I couldn’t stop. They thought I was crazy, and they kept kidding me, but here it all is. I don’t understand it.”

The key lesson from this scene, as Josh writes in his book, is that depth scores over breadth when it comes to learning anything. As he writes (emphasis is mine) –

The learning principle is to plunge into the detailed mystery of the micro in order to understand what makes the macro tick. Our obstacle is that we live in an attention-deficit culture. We are bombarded with more and more information on television, radio, cell phones, video games, the Internet. The constant supply of stimulus has the potential to turn us into addicts, always hungering for something new and prefabricated to keep us entertained. When nothing exciting is going on, we might get bored, distracted, separated from the moment. So we look for new entertainment, surf channels, flip through magazines.

If caught in these rhythms, we are like tiny current-bound surface fish, floating along a two-dimensional world without any sense for the gorgeous abyss below.

When these societally induced tendencies translate into the learning process, they have devastating effect.

Josh’s idea of making smaller circles is a great way to decide how to live, what to read, and how to invest sensibly.

Making Smaller Circles – Reading Take reading for instance. With so much literature around, and so much getting published day after day, it often gets challenging for most of us to decide on what to read. The breadth of what is to be read is huge, and is just getting bigger by the day.

Given this, as Josh writes, we have become like the “tiny current-bound surface fish, floating along a two-dimensional world without any sense for the gorgeous abyss below.”

The way out of this is to differentiate between reading that is enduring (durable – learning that has lasted a lifetime) and one that is ephemeral (fleeting – mostly information), like I’ve done in this chart below…

[Click here to open a larger image] …and then focus on stuff that is enduring. That’s choosing depth over breadth. That’s making smaller circles. And that’s exactly what I have been doing since the start of 2017 i.e., focusing 90% of my reading time on re-reading the super-texts (depth) and only 10% on others (breadth).

Here, I also take lessons from Seneca, a Roman Stoic philosopher who lived during 4 BC – AD 65. During the last two years of his life, Seneca spent his time in travelling, composing essays on natural history and in correspondence with his friend Lucilius. In these letters, 124 of which are available, he covered a wide variety of topics, including true and false friendship, sharing knowledge, old age, retirement, and death.

Coming to the topic of this post, here is what Seneca wrote in his second letter to Lucilius – On Discursiveness in Reading – which I am posting as it is here, and which contains the answer to the dilemma most of us face on what to read as investors (by the way, ‘discursiveness’ means moving from topic to topic without order) –

The primary indication, to my thinking, of a well-ordered mind is a man’s ability to remain in one place and linger in his own company.

Be careful, however, lest this reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady. You must linger among a limited number of master thinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind. Everywhere means nowhere.

When a person spends all his time in foreign travel, he ends by having many acquaintances, but no friends. And the same thing must hold true of men who seek intimate acquaintance with no single author, but visit them all in a hasty and hurried manner.

Food does no good and is not assimilated into the body if it leaves the stomach as soon as it is eaten; nothing hinders a cure so much as frequent change of medicine; no wound will heal when one salve is tried after another; a plant which is often moved can never grow strong. There is nothing so efficacious that it can be helpful while it is being shifted about. And in reading of many books is distraction.

Accordingly, since you cannot read all the books which you may possess, it is enough to possess only as many books as you can read.

“But,” you reply, “I wish to dip first into one book and then into another.” I tell you that it is the sign of an overnice appetite to toy with many dishes; for when they are manifold and varied, they cloy but do not nourish. So you should always read standard authors; and when you crave a change, fall back upon those whom you read before. Each day acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes as well; and after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day.

This is my own custom; from the many things which I have read, I claim some one part for myself.

Now, as I was reading Seneca’s letter, I was reminded of what Sherlock Holmes told his accomplice Watson in A Study in Scarlet –

I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it.

Holmes added…

Now the skillful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. he will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.

As years have passed, I have turned from trying my hands at speed reading – acting like Holmes’ fool who takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across – to slow, thoughtful reading and re-reading.

I do not read more than 1-2 books a month now, and that I find is a gradual enough pace that helps me assimilate the ideas I read in a better manner. As a wise man said, slow reading is not so much about unleashing the reader’s creativity, as uncovering the author’s.

Often it’s the same old books – the super texts – that I refer to again and again…for each time I go through them, I get a few new and brilliant insights that missed my eyes in the previous readings.

Making Smaller Circles – Investing To reiterate, the concept of making smaller circles, as outlined in Josh’s book, stresses on the fact that it’s rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the top, but rather a profound mastery of what may well be a basic skillset.

When it comes to investing, this concept applies in the way that you must do just a few small things right to create wealth for yourself over the long run. Pat Dorsey, in his wonderful book – The Five Rules for Successful Stock Investing – summarizes these few things into, well, just five rules –

Do your homework – engage in the fundamental bottom-up analysis that has been the hallmark of most successful investors, but that has been less profitable the last few risk-on-risk-off-years.

Find economic moats – unravel the sustainable competitive advantages that hinder competitors to catch up and force a reversal to the mean of the wonderful business.

Have a margin of safety – to have the discipline to only buy the great company if its stock sells for less than its estimated worth.

Hold for the long haul – minimize trading costs and taxes and instead have the money to compound over time. And yet…

Know when to sell – if you have made a mistake in the estimation of value (and there is no margin of safety), if fundamentals deteriorate so that value is less than you estimated (no margin of safety), the stock rises above its intrinsic value (no margin of safety) or you have found a stock with a larger margin of safety.

If you can put all your efforts into mastering just these five rules, you don’t need to do anything fancy to get successful in your stock market investing. Of course, even as these rules sound simple, they require tremendous hard work and dedication. As Warren Buffett says – “Investing is simple but not easy.” And then, as Charlie Munger says, “Take a simple idea but take it seriously.”

You just need a simple idea. You just need to draw a few small circles. And then you put all your focus and energies there. That’s all you need to succeed in your pursuit of becoming a good learner, and a good investor.

I believe that the process of working on the basics (the small circles) of learning or investing over and over again leads to a very clear understanding of them. We eventually integrate the principles into our subconscious mind. And this helps us to draw on them naturally and quickly without conscious thoughts getting in the way. This deeply ingrained knowledge base can serve as a meaningful springboard for more advanced learning and action in these respective fields.

Josh writes in his book –

Depth beats breadth any day of the week, because it opens a channel for the intangible, unconscious, creative components of our hidden potential.

The most sophisticated techniques tend to have their foundation in the simplest of principles, like we saw in cases of reading and investing above. The key is to make smaller circles.

Start with the widest circle, then edit, edit, edit ruthlessly, until you have its essence.

I have seen the benefits of practicing this philosophy in my learning and investing endeavors. I’m sure you will realize the benefits too, only if you try it out.

Value Investing Workshop in Bangalore and Pune – Registrations are now open for our Value Investing Workshop in Bangalore (23rd July, Sunday) and Pune (6th August, Sunday). Click here to register and claim an early bird discount.

The post Small Circles: The Theory of Mastery in the Art of Learning and Investing appeared first on Safal Niveshak.

Small Circles: The Theory of Mastery in the Art of Learning and Investing published first on http://ift.tt/2ljLF4B

0 notes

Text

Small Circles: The Theory of Mastery in the Art of Learning and Investing

One of the best books on the art of learning I’ve read is, well, The Art of Learning by Josh Waitzkin.

Josh is a champion in two distinct sports – chess and martial arts. He is an eight-time US national chess champion, thirteen-time Tai Chi Chuan push hands national champion, and two-time Tai Chi Chuan push hands world champion.

In his book, Josh recounts his experiences and shares his insights and approaches on how you can learn and excel in your own life’s passion, using examples from his personal life. Through stories of martial arts wars and tense chess face-offs, Josh reveals the inner workings of his everyday methods, cultivating the most powerful techniques in any field, and mastering the psychology of peak performance.

One of my favourite chapters from Josh’s book is titled – Making Smaller Circles – which stresses on the fact that it’s rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the top, but rather a profound mastery of what may well be a basic skillset.

Josh starts this chapter with the story of the protagonist in Robert Pirsig’s book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. This man is Phaedrus, a teacher, who in this particular scene is reaching out to his student who is all jammed up when given the assignment to write a five-hundred-word story about her town, Bozeman.

Here is that scene straight from Pirsig’s book –

…a girl with strong-lensed glasses, wanted to write a five-hundred-word essay about the United States. He … suggested without disparagement that she narrow it down to just Bozeman.

When the paper came due she didn’t have it and was quite upset. She had tried and tried but she just couldn’t think of anything to say. He had already discussed her with her previous instructors and they’d confirmed his impressions of her. She was very serious, disciplined and hardworking, but extremely dull. Not a spark of creativity in her anywhere. Her eyes, behind the thick-lensed glasses, were the eyes of a drudge. She wasn’t bluffing him, she really couldn’t think of anything to say, and was upset by her inability to do as she was told.

It just stumped him. Now he couldn’t think of anything to say. A silence occurred, and then a peculiar answer: “Narrow it down to the main street of Bozeman.” It was a stroke of insight.

She nodded dutifully and went out. But just before her next class she came back in real distress, tears this time, distress that had obviously been there for a long time. She still couldn’t think of anything to say, and couldn’t understand why, if she couldn’t think of anything about all of Bozeman, she should be able to think of something about just one street.

He was furious. “You’re not looking!” he said. A memory came back of his own dismissal from the University for having too much to say. For every fact there is an infinity of hypotheses. The more you look the more you see. She really wasn’t looking and yet somehow didn’t understand this.

He told her angrily, “Narrow it down to the front of one building on the main street of Bozeman. The Opera House. Start with the upper left-hand brick.”

Her eyes, behind the thick-lensed glasses, opened wide.

She came in the next class with a puzzled look and handed him a five-thousand-word essay on the front of the Opera House on the main street of Bozeman, Montana.

“I sat in the hamburger stand across the street,” she said, “and started writing about the first brick, and the second brick, and then by the third brick it all started to come and I couldn’t stop. They thought I was crazy, and they kept kidding me, but here it all is. I don’t understand it.”

The key lesson from this scene, as Josh writes in his book, is that depth scores over breadth when it comes to learning anything. As he writes (emphasis is mine) –

The learning principle is to plunge into the detailed mystery of the micro in order to understand what makes the macro tick. Our obstacle is that we live in an attention-deficit culture. We are bombarded with more and more information on television, radio, cell phones, video games, the Internet. The constant supply of stimulus has the potential to turn us into addicts, always hungering for something new and prefabricated to keep us entertained. When nothing exciting is going on, we might get bored, distracted, separated from the moment. So we look for new entertainment, surf channels, flip through magazines.

If caught in these rhythms, we are like tiny current-bound surface fish, floating along a two-dimensional world without any sense for the gorgeous abyss below.

When these societally induced tendencies translate into the learning process, they have devastating effect.

Josh’s idea of making smaller circles is a great way to decide how to live, what to read, and how to invest sensibly.

Making Smaller Circles – Reading Take reading for instance. With so much literature around, and so much getting published day after day, it often gets challenging for most of us to decide on what to read. The breadth of what is to be read is huge, and is just getting bigger by the day.

Given this, as Josh writes, we have become like the “tiny current-bound surface fish, floating along a two-dimensional world without any sense for the gorgeous abyss below.”

The way out of this is to differentiate between reading that is enduring (durable – learning that has lasted a lifetime) and one that is ephemeral (fleeting – mostly information), like I’ve done in this chart below…

[Click here to open a larger image] …and then focus on stuff that is enduring. That’s choosing depth over breadth. That’s making smaller circles. And that’s exactly what I have been doing since the start of 2017 i.e., focusing 90% of my reading time on re-reading the super-texts (depth) and only 10% on others (breadth).

Here, I also take lessons from Seneca, a Roman Stoic philosopher who lived during 4 BC – AD 65. During the last two years of his life, Seneca spent his time in travelling, composing essays on natural history and in correspondence with his friend Lucilius. In these letters, 124 of which are available, he covered a wide variety of topics, including true and false friendship, sharing knowledge, old age, retirement, and death.

Coming to the topic of this post, here is what Seneca wrote in his second letter to Lucilius – On Discursiveness in Reading – which I am posting as it is here, and which contains the answer to the dilemma most of us face on what to read as investors (by the way, ‘discursiveness’ means moving from topic to topic without order) –

The primary indication, to my thinking, of a well-ordered mind is a man’s ability to remain in one place and linger in his own company.

Be careful, however, lest this reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady. You must linger among a limited number of master thinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind. Everywhere means nowhere.

When a person spends all his time in foreign travel, he ends by having many acquaintances, but no friends. And the same thing must hold true of men who seek intimate acquaintance with no single author, but visit them all in a hasty and hurried manner.

Food does no good and is not assimilated into the body if it leaves the stomach as soon as it is eaten; nothing hinders a cure so much as frequent change of medicine; no wound will heal when one salve is tried after another; a plant which is often moved can never grow strong. There is nothing so efficacious that it can be helpful while it is being shifted about. And in reading of many books is distraction.

Accordingly, since you cannot read all the books which you may possess, it is enough to possess only as many books as you can read.

“But,” you reply, “I wish to dip first into one book and then into another.” I tell you that it is the sign of an overnice appetite to toy with many dishes; for when they are manifold and varied, they cloy but do not nourish. So you should always read standard authors; and when you crave a change, fall back upon those whom you read before. Each day acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes as well; and after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day.

This is my own custom; from the many things which I have read, I claim some one part for myself.

Now, as I was reading Seneca’s letter, I was reminded of what Sherlock Holmes told his accomplice Watson in A Study in Scarlet –

I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it.

Holmes added…

Now the skillful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. he will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.

As years have passed, I have turned from trying my hands at speed reading – acting like Holmes’ fool who takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across – to slow, thoughtful reading and re-reading.

I do not read more than 1-2 books a month now, and that I find is a gradual enough pace that helps me assimilate the ideas I read in a better manner. As a wise man said, slow reading is not so much about unleashing the reader’s creativity, as uncovering the author’s.

Often it’s the same old books – the super texts – that I refer to again and again…for each time I go through them, I get a few new and brilliant insights that missed my eyes in the previous readings.

Making Smaller Circles – Investing To reiterate, the concept of making smaller circles, as outlined in Josh’s book, stresses on the fact that it’s rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the top, but rather a profound mastery of what may well be a basic skillset.

When it comes to investing, this concept applies in the way that you must do just a few small things right to create wealth for yourself over the long run. Pat Dorsey, in his wonderful book – The Five Rules for Successful Stock Investing – summarizes these few things into, well, just five rules –

Do your homework – engage in the fundamental bottom-up analysis that has been the hallmark of most successful investors, but that has been less profitable the last few risk-on-risk-off-years.

Find economic moats – unravel the sustainable competitive advantages that hinder competitors to catch up and force a reversal to the mean of the wonderful business.

Have a margin of safety – to have the discipline to only buy the great company if its stock sells for less than its estimated worth.

Hold for the long haul – minimize trading costs and taxes and instead have the money to compound over time. And yet…

Know when to sell – if you have made a mistake in the estimation of value (and there is no margin of safety), if fundamentals deteriorate so that value is less than you estimated (no margin of safety), the stock rises above its intrinsic value (no margin of safety) or you have found a stock with a larger margin of safety.

If you can put all your efforts into mastering just these five rules, you don’t need to do anything fancy to get successful in your stock market investing. Of course, even as these rules sound simple, they require tremendous hard work and dedication. As Warren Buffett says – “Investing is simple but not easy.” And then, as Charlie Munger says, “Take a simple idea but take it seriously.”

You just need a simple idea. You just need to draw a few small circles. And then you put all your focus and energies there. That’s all you need to succeed in your pursuit of becoming a good learner, and a good investor.

I believe that the process of working on the basics (the small circles) of learning or investing over and over again leads to a very clear understanding of them. We eventually integrate the principles into our subconscious mind. And this helps us to draw on them naturally and quickly without conscious thoughts getting in the way. This deeply ingrained knowledge base can serve as a meaningful springboard for more advanced learning and action in these respective fields.

Josh writes in his book –

Depth beats breadth any day of the week, because it opens a channel for the intangible, unconscious, creative components of our hidden potential.

The most sophisticated techniques tend to have their foundation in the simplest of principles, like we saw in cases of reading and investing above. The key is to make smaller circles.

Start with the widest circle, then edit, edit, edit ruthlessly, until you have its essence.

I have seen the benefits of practicing this philosophy in my learning and investing endeavors. I’m sure you will realize the benefits too, only if you try it out.

Value Investing Workshop in Bangalore and Pune – Registrations are now open for our Value Investing Workshop in Bangalore (23rd July, Sunday) and Pune (6th August, Sunday). Click here to register and claim an early bird discount.

The post Small Circles: The Theory of Mastery in the Art of Learning and Investing appeared first on Safal Niveshak.

Small Circles: The Theory of Mastery in the Art of Learning and Investing published first on http://ift.tt/2sCRXMW

0 notes

Text

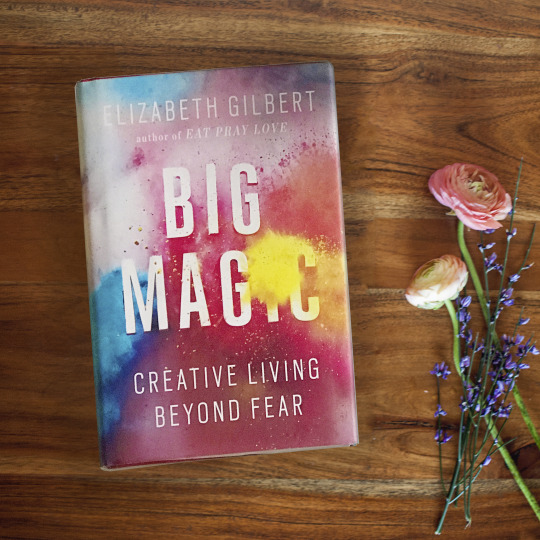

Five Inspiring Takeaways from “Big Magic” By Elizabeth Gilbert; Part 2

{This is Part 2 in a two part essay on Big Magic. To read part one of this post, click here, then come back to this one!}

3- The important difference between having a genius and being a genius. As Liz explains,

“In ancient Greek, the word for the highest degree of human happiness is eudaimonia, which basically means ‘well-daemoned’—that is, nicely taken care of by some external divine creative spirit guide. (Modern commentators, perhaps uncomfortable with this sense of divine mystery, simply call it ‘flow or ‘being in the zone.’)

But the Greeks and the Romans both believed in the idea of an external daemon of creativity—a sort of house elf, if you will, who lived within the walls of your home and who sometimes aided you in your labors. The Romans had a specific term for that helpful house elf. They called it your genius—your guardian deity, the conduit of your inspiration. Which is to say, the Romans didn’t believe that an exceptionally gifted person was a genius; they believed that an exceptionally gifted person had a genius.”

Liz and I both agree that this distinction, having a little genius helper vs. being a genius yourself, is hugely important to the creative process. In short, having a genius house elf takes the pressure off, which can be crucial. The magnificent thing is that it actually goes both ways in helping the precious human ego. When you fail at something creative, it is not considered entirely your fault—your genius failed to show up and help, and so your ego and reputation are saved. On the other hand, when you do manage to get that divine flow going and create something truly magical, you yourself cannot take all the credit, for surely something so amazing and inspired was only created with the help of your genius, and thus you are kept relatively humbled.

Somewhere around the Renaissance, when logic and reason began to overtake magic and mystery in every realm of thought, the idea of having a genius morphed into the idea of being a genius. Personally, while I love all of the modern amenities we currently enjoy (the computer and the internet whereby you are currently reading this, for instance), I think in this one aspect, this evolution has done a disservice to creators everywhere.

Imagine, if you will, a world in which the pressure is off. Imagine sitting down in front of a blank canvas, a blank page, a blank room, or at the very start of any creative project, and knowing that your only job is to show up, create, and have fun. The end results are not resting entirely on your shoulders. Imagine the actual fun you could have with the weight lifted like that. Imagine how little there is to fear. Doesn’t it sound rather, well, magical?

I happen to think we do put too much pressure on ourselves, particularly when it comes to creativity and inspiration. Too often we try to force it, to fit it into our regimented schedules. And I think that, like with anything we chase after desperately, the best way to find that divine moment of inspiration, is actually to relax about the whole thing and just play. Commit to showing up and doing the work, but allow yourself to creatively play too. Take the weight of the entire outcome off your shoulders. Maybe then inspiration, your genius, the flow, whatever you want to call it, will realize you are just having fun and will show up to help and to play.

4- Believe in the magic. There are a couple of ways in which this book gets just a little mystical. Some people have raised their eyebrows at this part of Liz’s theory on creativity, but I personally find it wonderful and curious. Because, yeah, it’s a little out there, but wouldn’t it be neat if it was true and she was right? And really, who’s to say?

Basically, Liz Gilbert’s theory is that ideas are magic. Not metaphorical magic, but actual magic. As she puts it she has “developed a set of beliefs about how it [creativity] works—and how to work with it—that is entirely and unapologetically based upon magical thinking. And when I refer to magic here, I mean it literally. Like, in the Hogwarts sense. I am referring to the supernatural, the mystical, the inexplicable, the surreal, the divine, the transcendent, the otherworldly. Because the truth is, I believe that creativity is a force of enchantment—not entirely human in origin.”

You really truly should read the book yourself to hear her explain it, but for a quick summary suffice it to say that Liz believes that ideas (all types of ideas) are invisible disembodied life forms whose sole purpose and directive is to find a human to collaborate with and make themselves manifest. This aligns well with Liz’s universalist leanings spiritually, and with my own. I understand it can be a little hard to swallow, but I implore you to read the countless examples of stories Liz provides and then decide how literally you want to take this theory. And, if you’ll permit me, I’d like to add a personal story as evidence to Liz’s case.