#but guess what? there's a difference between lusting over an animal (real or fictional) and lusting over someone wearing cat ears!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

wanting to rape kids isn't a kink. its a harmful paraphilia, commonly called pedophilia

Reminder that writing porn of an adult and a child isn't "just an ageplay kink". It's just you jerking off to child abuse

#also buddy.#buddy have you seen my profile.#buddy I'm a kitty.#buddy my biggest kink is petplay.#buddy i fucking love being taken care of as a human kitty and taking care of human pets.#but guess what? there's a difference between lusting over an animal (real or fictional) and lusting over someone wearing cat ears!#just like! how there's a difference between lusting over a child (real or fictional) and lusting over an adult wearing dino PJs!#(of course the first thing I thought of was dino PJs when I'm wearing them lol)#antiship#anti-ship#anti-proship#antipedo#anti-pedo#antizoo#anti-zoo

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I guess this is becoming a trend... I’m popping in before the actual intro to clarify-- if the text is in italic, it is me (Sugar) talking and regular is Spice. Alright? Cool. And so--

So, one night I’m going through youtube and I come upon this one shitposty video about some random anime that I’ve never even heard of. After doing some research, I discover that it’s actually based on a dating sim that I’ve also never heard of. As a joke I was like “Hey Sugar wanna watch this as a joke, it might be funny” and so we did. And uhm. Well.

Today we’re gonna be reviewing Brothers Conflict, aka Sweet Home Alabama 2: Electric Anime Boogaloo aka the anime that ruined our lives. [Again, disclaimer: neither Sugar nor I condone incest and/or pedophilia, two themes which are uh, very rampant in this anime which is why I cannot recommend it in good faith. It’s not good, don’t get me wrong. I can’t really say that I liked it even if watching it and ragging on it was kind of enjoyable, and I did get attached to some of the characters because that’s the kind of idiot I am. Also, we’re not shirking our duties to write I swear please don’t kill me--] Anyway, an obligatory SPOILER WARNING though this probably isn’t going in the main tag bc I do not want the fans to publicly stone me. Why are we reviewing this? Bc we need to talk about it somewhere. Though I say review lightly bc this... is really more of a critique.

ALSO we only watched the anime, idk if things are different in the game. There is no full english translation for the games and most of the LP channels have been copyright striked, so please don’t come at us for not knowing anything. I also know that otome games and dating sims don’t tend to translate well to anime, and I will be addressing this later.

So, dear god, where do I begin.

Where do we begin indeed? How about the fact that her name is Ema and I had to google to remember the heroine’s name? Also, she is seventeen.

Our plot, or well... what you COULD call a plot, I guess, if you REALLY wanted to give this anime that much credit, focuses on the aforementioned seventeen year old Hinata Ema, who has an absent father who apparently FOUND THE TIME TO FALL IN LOVE AND GET MARRIED BUT NEVER HAS A SECOND TO SPARE FOR HIS ONLY CHILD, RINTARO I SWEAR TO GOD I AM TAKING CUSTODY OF YOUR CHILD. HAND HER OVER-- Anyway. He’s getting married to a woman who has 13 sons (jesus christ ma’am have you ever heard of a condom?) and he decides to move her in with them because... I guess he has less braincells than I have balls, which is to say, zero. Hi, I’m trans.

So, Ema moves in with them... along with her talking grey squirrel, Juli. Juli is... interesting and by interesting, I mean-- ABSOLUTELY PUZZLING. He, apparently, has seen the majority of Ema’s life from babyhood to teenagerhood and can talk but is only understood by Ema (who he calls Chii) and Louis, the eighth son in the Asahina family. It is never explained why, or how Chii came across him or how in an episode, a single episode, he becomes human because why the hell not, I guess??? (Also, he is pretty. YES. I said it. Fight me.) [Quick Spice intervention, this squirrel can talk to people, transform into a human, enter dreams, and live way longer than a squirrel should since the average lifespan of a squirrel is like 6 years in the wild. Juli is apparently a god as none of this is EVER explained.]

And when she meets the Asahina family, it’s pretty much immediately chaos because these heterosexual (I guess? They look like a bunch of twinks to me but there goes anime trying to convince me that straight people are real and not a lie made up by Trump) men have NEVER and I mean NEVER known a woman in their entire lives, since they seem to want to bang their stepsister immediately. And most of them are GROWN ASS ADULTS. Only three of them are actually minors (though Iori is 18 and only one year older so I guess??? It’s okay??? But still weird) and one of them is a 13 year old who looks and acts like he’s 8.

Oh, and did I mention that out of these boys, only the adult triplets and the abusive asshole 16 year old get any kind of characterization AND character development? I mean, Subaru gets an “arc” if you can call it that, but really, they don’t give him much... personality. You could replace him with a cardboard cutout and it’d be the same. I feel bad for him (but not really because dude you are 20 and she is your sister, what the fuck--)

But if there’s anything good about this anime, it is the characters themselves. Several of the boys have redeeming qualities and interesting personalities and quirks, as well as interesting relationships and dynamics with each other. Yes, some of them are lacking in the plotline department while others may have decent plotlines and lack personality, and then some of them are just given absolutely nothing (COUGH Masaomi COUGH Ukyo COUGHCOUGHCOUGH Iori, and by the way, what the fuck is that game plotline bc I read the wiki since I wanted to know more about him. We don’t have time to unpack the mento illness luv. But you’re telling me they had all this meat to work with and they threw it in the trash and gave him nothing? What the hell?) And if anything, I feel as if the characters themselves are crippled by the plotline. If given a different story, perhaps, they may have room to shine, because a lot of them are compelling if not lovable (though some may not be... lovable. COUGHFuuto, at least not for me.) If you want to see our review on the characters, we’ll put out another post.

Iori... Iori has a hell of a plot in the game, according to the Wiki but I can’t blame the writers for not exploring all of it because whoa. It is dark and not in a good way. But back to the subject at hand... I agree with Spice. I do/did like quite a lot of the characters... provided the entire romantic plot is taken away but we will go into more of why the plot is problematic below. All I can really add is: There is a baby in this dumpster and canon has been taken out back to be shot like a lame horse.

This brings me to a point in which I would like to pause the character discussion and bring up a glaring flaw with this anime in general (aside from the... plot. Look, I’m not a huge fan of weird stepsibling stuff but I think that if you want to do something like that, there are ways to do it and ways not to do it. This was the way not to do it, which I’m getting to). The biggest thing that made this anime so uncomfortable was the imbalance of power dynamics. Why is the protagonist 17 when most of the love interests are 18 and older, and I mean much, much older? And she’s not any 17 year old... she’s a lonely, neglected girl who is starved for the love of a family. This makes her easily manipulated by the brothers, who clearly desire her for less than wholesome reasons, and that makes it skeevy. I’m not sure why there’s such a fetishization of nonconsent in media, as if it’s fine for as many men to lust after female protagonists as the writer desires BUT the woman can’t want a single one of them in return. It’s creepy, and quite frankly, I am very much over it. I also get that the age thing is probably a product of the protagonist of a teenager oriented dating sim not translating well to an anime (because really, all otome game MCs are meant to be a neat little pair of shoes for the player to imagine themselves in), but why are we fetishizing a teenager being groomed by adults anyway? Especially adults who have this much power over her to begin with? The power dynamics bring this plot from “Oh, this might be kinda trashy but it could be entertaining” to “This is extremely creepy and rapey and kind of a dumpster fire.”

This is also true. If we were to take age into consideration, Fuuto, Yusuke, and Iori would be the three candidates left for Chii. This is taking out the youngest as well, who is... thirteen, I think? But anyway, (I know I am probably going to get some hate for this but go for it), I am into stories that explore the stepsibling thing and it can make a good narrative-- but before everyone gets uppity: There is a line between FICTION and REALITY and I do not condone real life incest but a story is a story and there are ways to frame it that make it clear that it is not a romantic thing, or acceptable. This anime does not do that in it’s dynamics because some of the brothers do start off in that very firm caregiving, family role and it is a sharp turn into romance that makes you go, “?” or in Fuuto case, a blending that does lean into fetishization.

All in all I think the plot maybe could have been okay? I’m not saying it isn’t problematic, because we all know it is, who are we kidding? But I don’t think it’s wrong per se to explore family dynamics with romance and to understand where the line should be drawn, and maybe exploring the definition of family itself. I have seen fanfictions with similar tropes ask those questions and explore the concept beautifully without romanticizing or fetishizing incest and unhealthy power dynamics. It could have been good, and I get that perhaps I’m barking up the wrong tree by expecting mature themes in an anime based on an otome game, but it also could have been a lot less... creepy (I have used that word so much that it looks wrong now) even if it wasn’t the greatest thing ever. But again, what was I expecting? I watched this whole thing as a joke and ended up attached to the characters like a fool... That tends to be a trend here, and this is why we are so salty all the time. So anyway, stay tuned for our review of the characters! We may not cover all of them since some of them don’t really get anything, but we’ll cover what we found interesting.

#spice talks#sugar speaks#anime and game reviews#sweet home alabama: the anime#not putting this in main tag

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

July 9: Star Trek 1x05 The Enemy Within

Today’s ep: The Enemy Within. Overall this is a good ep, but I don’t know that I entirely agree with its thesis, and some parts of it are so uncomfortable that they mess with my general enjoyment.

Kirk, being encouraging of his crew: “That will make a good specimen.” I like how it’s just one line but there’s such confidence about him. They have to remind you of his normal self fast because he’s split for 99% of the episode.

Sulu: “That’s nippy.” I love Sulu.

So they just find an alien dog on the planet and decide to steal it? Lol your fav is problematic Enterprise crew.

(Like how they just never explained why they sent the dog up by itself later lol.)

I forgot that it was the ore that messed with the transporter. That’s a cool idea; makes sense. Alien ore gets in your system now weird stuff happens.

Evil Kirk appears and no one sees him--that’s why you don’t leave the transporter room unattended like Kirk said!!

Honestly imagine how wild seeing this when it first aired and not knowing much about Star Trek would be. Weird new sci fi show’s been on for a month and suddenly there are two Captains!! What!?!?

Even the way Evil!Kirk touches the ship is lascivious.

Bones is a good doctor. He really does have a good bedside manner; I don’t feel like people remember this about him enough.

He also keeps brandy in sickbay lol.

This scene with gratuitously shirtless Kirk and distracted Spock... it doesn’t look anything less like a porno in context honestly. I know Spock is supposed to be distracted because he’s hearing information that doesn’t make sense but Kirk is just so obviously turning on the flirt face (aka his usual face with Spock) and he’s shirtless so... the distraction is real and multi-faceted.

Ooh, Janice is an artist! I love her little rotating mirror thing.

This scene is so terrible. Really upsets me. Surely they could have found some way to portray ‘pure selfish id’ without going immediately to sexual assault.

Evil!Kirk wears so much eye makeup.

It’s interesting to me that Good!Kirk is so obviously not the real Kirk either, right from the moment he steps off the transporter. (Not to be that person again but Shatner is a better actor than people give him credit for being.)

Spock will save the day! I know that Rand calls for him because he’s First Officer but it’s still interesting that she goes for that name over, like, security.

Evil!Kirk is also where Kirk keeps all his dramatic tendencies.

I feel so bad for Janice in this scene. “What was I supposed to do? He’s the Captain.” Anyway this is why this is still a problem.

That dog omg.

“Set phasers to stun.”

“The search party is to capture you.” Yeah, that’s hard to explain. “Hey, crew, we’re going to play a little game of hide and seek. I’ll hide first.”

Man this conversation between Kirk and Spock. Leadership is one of my favorite themes in ST and Kirk is probably my favorite fictional leader of all time okay so this means a lot to me. “You don’t have the right to be vulnerable in the eyes of the crew.”

Spock is honestly just so on Kirk’s side, at every single moment. He believes him, trusts him, knows who he is, is loyal to him, is honest with him, knows how to handle him, how to care for him.

Spock likes the dog. He likes animals, in general.

The phaser vocab is so different this early on. “Base cycle.”

Good thing Kirk has makeup readily available to cover up his scratches.

My mom suggested transporting some blankets to the planet. But what if they split into evil blankets!! (Interesting that inanimate objects DO split too though.)

I feel like Kirk tried to do a Vulcan nerve pinch there lol.

“If I’m to be the Captain, I’ve got to act like one.” Immediately goes to a shot of his evil self climbing on equipment.

Spock: I always have a point.”

Spock listing out Kirk’s good qualities: his intellect, compassion, love, tenderness. Telling, lol. A lot of synonyms for how much he loves and admires Kirk. Kirk appreciation hour.

“If I seem insensitive to what you’re going through, Captain, understand: it’s the way I am.” I love this line, it’s perfect, because it has two meanings: how I am is unemotional, which causes me to seem insensitive; but also: I go through what you’re going through all the time, it’s how I am.

“Lower us down a pot of hot coffee or some rice wine.”

Poor Kirk, so many struggles, not enough snuggles.

There’s no way people could live through those temperatures in those clothes and not die. Sulu calling for room service. I love him. (Why did they drop his sense of humor in the movies???)

“A thoughtless, brutal animal... yet it’s me.”

I have a lot of mixed feelings about the main thesis of this ep. But. I do love that Kirk’s courage is in his good side.

And so much compassion....”Don’t hurt him. Don’t hurt my evil side.”

Poor animal. Goes through such a confusing experience. Then dies.

Second Officer Spock. I’ve seen people make a big deal out of this but it’s pretty obvious to me this is supposed to mean “Second in command.” As in Kirk is the “First Officer” as the Captain and Spock is second. He behaves in all ways as the second in command, right down to making that log entry at all.

The AOS verse should have rebooted this ep instead of Space Seed (I say every single episode). I mean, STID had as a theme “Kirk learning what it means to command.” That could be tied in! Also can you imagine, two CPines? Two??

Half alien Spock.

Jim’s compassion is paralyzing him.

Aaaand we’re back on the creepy train with Evil!Kirk.

Evil!Kirk doesn’t care about the crew at all. He can make decisions fast because he only cares about himself, so there’s always an easy answer.

Of course he and everyone else looks to Spock as the authority on Kirks.

Evil!Kirk knows he’s not the dominant one here, that re-combining with Good!Kirk means a certain ‘death’ or at least... being sent back to the depths.

Spock at the transporter as if this were even his department lol.

“I’ve seen a part of myself no man should ever see.”

That flirty face he gives Spock though oml. Get a room.

Ugh Spock’s last comment was so ragingly inappropriate. Hate it. But also, read it as an expression of his own extreme jealousy because he’s definitely a jealous person. Just put through the ‘sexist 60s man’ dialogue-writer translator.

So again, I like the idea of this ep and a lot of the details but the details I don’t like are......hard to ignore.

I liked that the bad side was dramatic, selfish, confused, entitled, and it made sense that he was violent and even lustful. And I liked that Kirk had such a hard time seeing that part of himself and acknowledging it. And I do think it's a good lesson/message that we need to understand our own worst impulses and that those impulses are part of us and maybe even tied to parts of us that we need. But the implication that everyone's a little rapey and that the events of this episode necessarily mean Janice has to work for someone she knows is inappropriately lustful toward her just... are really hard for me to entirely get over.

Honestly her reaction just really makes me so sad. And it annoys me that no one stands up for her, no one says that the Captain was wrong and she didn’t deserve that treatment, “imposter” or no. I guess that's what bothers me more than that Evil!Kirk went immediately to assault, b/c the idea IS that he is lustful, violent, and completely selfish. He cares about himself, his survival, his ship, what he owns, what he deserves. Maybe it is natural he would let the power go to his head and seek out someone who he knows he could manipulate easily into giving him something he wants. Maybe it's no different in a way from stranding the crew on the planet. But no one says "hey, that's wrong what he did. You're entitled to respect from the Captain." And I wish someone had.

I recognize this was made in 1966 and I do generally give ST credit within the context within which it was made, but I am a 2020 viewer and the ep certainly hits home given, you know, everything, so... just some thoughts.

Anyway, another thing I was thinking about during the ep was that I feel like I forget that Spock has two "warring halves" b/c he's half human. Because before he put it that way, I was thinking about how the war in him is between his natural Vulcan emotions and his Vulcan teachings. But now I wonder if the whole "Vulcans are super emotional" thing might actually be quite late in the canon, and initially they were intended to be naturally "emotionless.” But basically I don’t actually know how I headcanon the human and Vulcan halves of him interacting... You’d think I would lol but my take in haicg was really... pretty focused on the Vulcanness of him. I guess I thought of the human half as more of a cultural thing because physically, emotionally, psychologically, and physiologically he appears to be primarily Vulcan.

Talking about this more with my mom, it’s making more sense to me... it is cultural and it’s about expectations. He wants to “honor his father’s teachings” and be Vulcan. But he has a whole half, a whole side of his family, with different teachings and beliefs--what to do with them? When he’s around Vulcans, they are obsessed with his human side. When he’s around humans, they see him as fully Vulcan--which is much easier for him and why he seeks them out imo--but it also is a constant ignoring of part of him he feels guilty for ignoring. When McCoy tells him to be more emotional, does a part of him wonder if he should? For his mom? But then... Vulcans don’t choose to be logical for fun. It’s for safety, it’s for survival. So how can he do anything else but follow his father? Who he also doesn’t speak to for 20 years and has a super complicated relationship with! So it’s difficult.

Anyway. That was an emotionally intense experience for this human person. The next ep is Mudd’s Women, one of the weaker S1 offerings, but still a classic as per usual.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I’m doing a module on Kubrick, and I’m bringing you along for the ride

Context; I’m required to upload weekly blogs about the lectures and screenings and readings from the week. This is that.

Okay, so first is the lecture; one of the first things Nathan said is that Kubrick is that he has a film in every genre other than a western - we were not given a reason why; I guess he just hates them.

After my first introduction to Kubrick, I didn’t really know what to think about him - he seems a little high maintenance because he was very nit-picky about something changing on his set, whether that was a slight difference in the lighting or a prop had shifted. It should come as a surprise to no-one that Kubrick was an avid photographer as a young man because the skills he learnt whilst as a photographer at Look Magazine have bled through into his film-making. I also enjoy photography, so I connected with him at least on a very surface level. His other hobbies, like chess and other physical sports, also can be seen manifesting themselves through his work - some good, brief examples are his three short docu-style films. Day of the Fight illustrates his passion for sport and shows how he experimented with his photography at the same time; a good example of this is what I am calling the ‘under-the-fight’ shot, where the boxers are shot from underneath - we can see both of their faces and where the blows are hitting, and it gives the audience a glimpse into what it might have been like to see the fight live. Perhaps his strength and talent in photography lead people to see him as a “New York Intellectual” - part of me thinks that the deep and entwining themes came along after his experience as a photographer.

As most filmmakers do, Kubrick responded to the debates and ideas of his time, and made films within the context of those issues (more on this later). He seemed a little stuck up, especially when considering that he did not compromise his stylistic or intellectual integrity; some might say that that is noble of him, that he remains true to himself and the standards he upholds, but try thinking about it from the other crew’s point of view - he might have turned down their ideas because they did not align with his. This is, of course, speculation and I have no evidence to prove either way. Also, I’ve been informed that he had to check everything himself and didn’t trust other people to make his imagination come to life, which seems controlling to me - for example, he would often insist on holding the camera himself in order to effectively portray a point of view or something. I think if he could direct, hold the camera, do all the edits, record the sound, and act all the characters, he would. It would appear that he wanted everything to be just how he wanted it - but maybe that’s my pessimistic mindset coming through.

Let’s talk about the first three shorts Kubrick was commissioned to do. The first was called “Day of the Fight” in 1951 and is a documentary about Walter Cartier, an Irish middleweight boxer preparing for a fight. The narration, paired with the footage shot by Kubrick himself, informs the audience of how a semi-professional boxer prepares for a fight. Through this short piece, we can see Kubricks interests creep in - his enjoyment of sport and passion for chess is represented by the boxing itself, but also his love for animals can be seen through his inclusion of Cartier's dog. It is in this piece that the first ‘under-the-fight’ shot is used, emphasising his love for interesting shot and photography. His next short is called “The Flying Padre” (also 1951) and is another docu-piece about the priest Father Fred Stadtmuller who used his plane to spread the word of God and reach as many people as possible. He is portrayed as a lawful good hero, a Superman type. This is the shortest of the three, and there isn’t much more to say about it. The final short Kubrick released was made in 1953 called “The Seafarers”, and contained information about the perks that these navy-esque men receive for their service. It sheds an innocently positive light on the domestic aspects of their work and the options available for them (although they do say the word ‘seafarers’ far too much). It looks like some of the short were staged, especially as Kubrick probably would have had only one camera, but that is a common method to use when creating docu-style pieces. One question I did have though, nothing to do with Kubrick though, is how are the families of the seafarers perceived? Are they judged or pitied for not having a man around (because it was the 50′s, ya know)?

I’ll briefly (or not) discuss the other two feature-length films that Kubrick released about the same time. In 1955 he released “The Killers Kiss” whose story revolved around an ex-boxer and a dancer who fell in love and wanted to run away together to escape her creepy boss. As is the case with all of Kubrick’s films so far, this one started with some internal monologuing. The first 15 minutes or so heavily mirror “Day of the Fight”, from the vanity inspection beforehand to the ‘under-the-fight’ shot, which makes sense - Kubrick was only in his 20s when both of these films were released and his experience (like most of ours) was limited at the time (also we all draw inspiration from previous work/real life or whatever). Other than the glaring social issues (gotta love the 50′s) and peculiar plot holes, I felt that the music offset the desired atmosphere during scenes that were meant to be particularly tense - we learned that Kubrick enjoyed his music, jazz, in particular, so I find it strange that he would not try to better match the music with the intensity of the scene; perhaps it was that he did not have much music to work with. Kubrick uses a lot of noir features in this film e.g. harsh shadows, casting light through slatted blinds, utilising the aesthetic of smoking and fedora hats standing at street corners and at the ends of dark alleys, which I always enjoy. The second film we were introduced to was “The Killing” from 1956 - according to Nathan, this film inspired Tarantino to use split narrative, and this is one of the worlds first heist films. I don’t have as much to say about this one, both sport and chess can be seen within it illustrating Kubrick’s love for them both, it has a lot of noir tropes, and I think there was a gay couple in it? But I might be reading into it a little too deeply. There was an interesting switch of gender roles between two couples - in one, the man was dominant and overbearing, but in the other couple it was the woman who essentially bullied her partner, which was potentially quite progressive when considering the time in which it was released.

Here’s a brief (actually, this time) intro to the film I want to focus on - “Fear and Desire” was the first Kubrick film I watched, I had no expectations or thoughts about it beforehand and didn’t really know what to make notes on. After doing some reading, certain things became clearer, so I’ll pair the reading with some of my notes on the film itself.

In the introduction of the reading, James Enyeart talks a lot about the implications and developments of photography in the mid 19th century - these are some of the attributes he gives it;

- highly graphic and structures

- photographers had a keener eye

- composition gave structure and harmony

- gave a more aesthetically pleasing view of the world

- the more graphic an image and the more dramatic it’s presentation, the stronger the emotion

I agree with these conclusions - obviously, technology has advances since then, but these comments still ring true today. Additionally, Enyeart discusses photos in relation to the context they provide, and I have a theory; if a collection of photos can give more context than a single image, therefore a film (which is a series of photos shown in quick succession) can give the maximum amount of context? Alternatively, it could have the opportunity to convey multiple contexts, which could be considered themes?

Word of the day; Apotheosis – a perfect form or example of something, the highest or best part of something, elevation to a divine status.

I also agree with Enyeart’s comment suggesting that the overlap of cinematic photography, fiction, reality, and documentary style is the apotheosis of film.

Cherchi Usai’s chapter on Kubrick and “Fear and Desire” is more tailored to discussing the film – also I didn’t read any of the other chapters because I didn’t have time and that shit is long.

One of the biggest things discussed is how Kubrick hated the film in question (and I have to partially agree – it’s not great), but what is interesting is that no one can seem to agree whether it is a masterpiece or not. After the film was made and ready to be distributed, Kubrick was in love with it, as any young creative is with their most recent work. It is said he called “it’s structure; allegorical. It’s conception; poetic.” However, soon after its public release, critics called it “amateur” and said nothing more. However, after the initial hype, Kubrick ignored the fact that it ever existed, and it was after that that critics and fanatics thought the work to be more than it’s original worth. To me, it feels like a stranger wandered into Kubrick’s childhood bedroom and riffled through his GCSE artwork to find something for a museum – I do not understand why “Fear and Desire” is obsessed over.

It was at this point that I debated whether I wanted or even cared about the origins of the film, but my degree told me yes.

Also, keeping a camera in a paper bag is terrible camera care and hurts my physically.

One of the main points that were discussed was the theme of obsession – Kubrick had obsessions in his life, and he made films surrounding obsessions of different themes; death, lust, war, money, fear (also narration and film noir for Kubrick himself). In the film “Fear and Desire”, those obsessions are made manifest through Mac’s conversation with Corby about the Governor – he is obsessed with killing the enemy and winning the war, so much so that he died for his cause.

The final point to discuss is the double use of the actors – the actor for Corby also plays the Governor, which adds an air of humanity. Additionally, the narration played over their images is existential and inward-looking, therefore humanising both sides of the war.

1 note

·

View note

Note

holy shit, who the fuck are you even??? your fantastic beasts posts are so pretentious and annoying, you just keep assuming a bunch of shit out of things you're taking out of context and you talk as if its confirmed canon, when it's obviously NOT, like, do you have the fucking script right there on your hands??? no??? then shut the fuck up and stop clogging the tags with your stupidity.

Dear Sir, or Madam, Thank you for taking the time to write me such an informative and interesting response to my commentary on recent events regarding the Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald. As you clearly have some questions that you want answered allow me to answer them for you.

To the first inquirer, you ask who am I? (Although the correct terminology is either “Who even are you, or who do you think you are” ) For the record I am a college teacher that teaches game design and development, specializing in the writing aspect for games (since they tend to need work on telling stories) who holds a Bachelor degree in Fiction writing and is right now working on a masters computer science degree. My focus in college was understanding how fictional stories are created and how they work, in both written and visual mediums. Does that answer your question there? Oh and I was originally going in for animation and journalism, so I have a background there as well. Also I have a strong understanding in article writing and how opinion pieces vs. fact pieces are written. Moving right along then. You mean my opinions on the matters in regard to the reaction over the whole issue with David Yates comments? Or are you talking about the fact that I laid out all the facts and links to articles with quotes, and went into explanation as to why Yates would have put the terms that way and theorizing what they are planning. You see, I was taking what was written in the books previously in Harry Potter in regard to both Dumbledore, Grindelwald, Ariana and Aberforth. The facts are in the book as stated:

1. Dumbledore and Grindelwald were friends during the time that his sister was dealing with her issues.

2. Aberforth noted in the book that Ariana was traumatized by muggle boys causing her to repress her magic and become ill.

3. We know from Credence that repressing your magic early can cause you to become a Obscurial. Due to this one can then hypothesis that Ariana was a Obscurial as well.

4. We know, thanks to the books and Dumbledore talking to Harry that Grindelwald was using him.

5. We know that Graves/Grindelwald was using Credence’s abilities as per the first Fantastic beasts. We can then, assume with little to no guessing that Grindelwald saw a way to Ariana through her brother and used him to get at her and this probably lead to her untimely death.

6. We know how Grindelwald operates due in part to his acts as Graves and from what Dumbleore said in the books as well, as well as the memories and Aberforth’s comments.

7. Rowling seems to write her bad guys in similar fashion, not exactly the same, but very much alike.

8. Tom Riddle is a prototype to the new version of Grindelwald in this movie (since we’ve seen how he uses his words to emotionally manipulate people) and more than likely she’s using a lot of Tom’s charm on Grindelwald (as per the comments of him -Grindelwald being very charming in the books).

Taking these facts into consideration it’s not too hard to assume, at all, that Grindelwald is going to use that manipulation to get under various peoples skins and cause fractions between the cast of characters. Just as Voldemort got under Harry’s skin regarding Dumbledore, so too, it would make sense, that Grindelwald will do the same to Newt. Making him question his mentor and forcing him to grow as a person.

Also, for fact, as I stated in my posts, if you look at the time period of the fight between Grindelwald and Dumbledore (not till 1945) it would make more sense for her as a writer to do a build up over the next 2 (FB3 and FB4) or 3 (FB3, FB4, and FB5) movies with Dumbledore and Grindelwald, than to front load the movie here with them and have a weaker meeting in the last where (let’s be honest here with 5 movies you know the last will be at the end of WWII in regard to this since it’s been set up in Harry Potter) they have their fight.

Keep in mind that that final battle was where Dumbledore procured the wand of the hallows. We know that, from the books, Dumbledore owned at least two of the hallows and not the third, though it was in his possession after James Potter’s death and he returned it to Harry and had never used it. We can, assume then, that Newt’s journey has ties to the hallows, given the title has all three items in there, and we know Albus at this point doesn’t have the wand but Grindelwald does. I was off about the mirror and for that I apologize to my readers. However I don’t think I’m wrong on the idea that Grindelwald is going to France after one of the hallows (either the stone or possibly one of the Potters that owns the cloak or possibly one of the Gaunts, since they have the stone with them -although given the time frame for Morfin’s imprisonment I don’t see it being the stone so possibly the cloak) it would fit his MO so far, seeing that he wants to unite all three for world dominance. We can assume a lot of things based on what we’ve seen before in her writing. Writers tend to, and I know I’m guilty of this as well, have a pattern for their stories, especially when it pertains to situations like Harry Potter or the Fantastic Beast Series. The similarities are hard to dismiss. Slightly nerdy and unusual hero makes friends with a smart and talented girl and a slightly goofy guy. Trio is harassed by a charming yet ultimately dangerous big bad that wants to use some powerful mcguffin (object or person), to take over the world. Said trio needs to find a way to stop said person and uses help from mentor ally. Said ally has a dark past with the villain that is only revealed with time and for dramatic purposes. Main hero suffers powerful loss that propels them into action to defeat said bad, no longer for the sake of the mentor, but for their own sake. Wash, Rinse, repeat. Now which story am I describing Harry or Newts? This is why I honestly think the things I’m saying in the posts are true. There’s enough there if you read a lot of books and understand the patterns of a story, particularly the hero’s journey, to get why things are set up the way they are and why Yates and Rowling are being the way they are. It’s all down to how well you can critically read a book or watch a movie. If you know the hints, the signs, everything is laid out for you there in the trailer and the previous movie. Newt’s feelings for Leta, Leta clearly being a Lestrange and more then likely working for Grindelwald given how her father is a dark wizard that has ties to him. Hell her cousin is tied to Voldemort. Rolf being the hero that Newt wishes that he was in some ways. Leta being Newt’s lost love, etc. Anyone can see where this story is going if they look hard enough at what’s presented. Clearly there are parallels between the relationship of Dumbledore and Grindelwald and Newt and Leta. There’s enough hints there to show that she’s not a good person and probably hurt him emotionally and it’s not a far jump to assume that a Lestrange may fall for someone that’s charming and evil like Grindelwald, who could use that lust for power to do some bad things. It’s all there in the tropes! I really don’t need to have a copy of the script that’s coming out in my hands to understand what’s going on because we kind of read pretty much a lot of it via other books and her own novels and the way Jo tends to set things up.

If however you are talking about my notes early on about the situation on the romantic aspect of Dumbledore and why he hides himself. Again, I am basing this on history, and, as we’ve seen in the books, the Wizarding world is just as predjudice as the Muggle world is. There’s enough evidence in Harry’s books to indicate that a lot of the laws that govern modern wizarding society probably have ties (namely in Britian) to the laws that were governed by the Queens and Kings of England. We’ve already seen the ties via the fact that Merlin is a real person so that would mean that, in all likelihood, so too is King Arthur. We also know that there are probably half bloods working for the ministry to tie in modern day british laws to the wizarding world, so It’s not that far fetched to assume that the wizarding minsitry has a similar law set up that I mentioned in my first post. If you are objecting to the fact that I used that fact, well I’m sorry, but it does fit within the aspect of the world that she is building as we’ve seen that most of the Ministry figures have duplicates in the Muggle world, down to the detectives and cops in the form of Aurors of different ranks. We’ve also seen that the MACUSA also has a similar set up to the pre-1940s version of the US Feds, and we have speakeasies and mobsters, meaning that the Wizarding world there is also in prohibition. And, if that’s the case, then there is no reason to not at all assume that the Law that I mentioned was still in effect in Great Britain where Dumbledore is living. If you object to that, well then sir or madam, I’m not sure what else to tell you other then I did my research before I wrote my counter pieceI highly doubt that she didn’t, at the very least, know about this law and other laws like it since, you know, Jo grew up when a lot of the laws were being looked at by the LGBTQ+ activist of the time so that they could . Also, it wouldn’t be to hard to look up that sort of info, since she clearly looked up about prohibition to include the fact that at the dining table they were drinking anything but liqueur, as that was not available at the time period of the film. Again, it all comes down to the facts that we have been presented, the opinions we have based on our own views, as well as the information we can gather from both her former works and works of others regarding how a story works in the visual medium.

As I said before, it’s their opinion that’s fine, but a lot of people are overlooking a lot of facts from the books to build this case against them, when non of us have the script at all. But as I said, critically watch the film and then the trailer and focus on the idea of the Hero’s journey and the 13 aspects of it, then think about what we know about Dumbledore, Grindelwald, Newt and compare them to Harry and Tom and you’ll see a lot of similarities to the original story. Not quiet the same but it’s still all there.

As for being silent, I don’t think so. I had my say on the matter, and, when the film comes out, and I turn out to be right on all my points, I’ll be pleased. If I’m wrong and all my theories turn out to be false, ah well. Regardless I still hold that the fact that both Yates and Rowling seem to be hinting at a longer story being told with Dumbledore and Grindelwald and the given history in the Harry Potter books, and the fact that Newt is the lead and it’s his journey, that we’re not going to see a lot of the relationship deeply until film number 3 or 4 with the climax of all that being in film 5 in 1945, and that’s my honest opinion on it.

#asking questions#anonymous#fantastic beasts 2#I answered this and frankly I'm kind of relieved to see this come out at me#at least I know people have been reading it#I hope others do try to understand where the hell i'm coming from#and I think it's fine to have your own opinions on this matter#if you don't like what they said that's fine#I'm just personally tired of seeing people lambaste others over a choice of word#especially when it's a writer who's trying to tell what would technically be a multibook epic#not to mention them trying to keep secrets about things down so as not to wreck the story for those that didn't read the books#because you know there are some people that just don't like to read#but liked the harry potter movies

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wiggs Dannyboy’s Theory of Floral Consciousness

"Humankind is about to enter the floral stage of its evolutionary development. On the mythological level, which is to say, on the psychic/symbolic level (no less real than the physical level), this event is signaled by the death of Pan. Pan, of course, represents animal consciousness. Pan embodies mammalian consciousness, although there are aspects of reptilian consciousness in his personality, as well. Reptilian consciousness did not disappear when our brains entered their mammalian stage. Mammalian consciousness was simply laid over the top of reptilian consciousness, and in many unenlightened—underevolved, underdeveloped—individuals, the mammalian layer was thin and porous, and much reptile energy has continued to seep through. When our remote ancestors crawled out of the sea, they no doubt had the minds of fish. Characteristics of mammal consciousness are warmth, generosity, loyalty, love (romantic, platonic, and familial), joy, grief, humor, pride, competition, intellectual curiosity, and appreciation of art and music. Inlate mammalian times, we evolved a third brain...whose principal part was the neocortex, a dense rind of nerve fibers about an eighth of an inch thick that was simply molded over top of the existing mammal brain. Brain researchers are puzzled by the neocortex. What is its function? Why did it develop in the first place? Moreover, neuromelanin absorbs light and has the capacity to convert light into other forms of energy. So Ely was correct. The neocortex is light-sensitive and can, itself, be lit up by higher forms of mental activity, such as meditation or chanting. The ancients were not being metaphoric when they referred to "illumination." With the emergence of the neocortex, the floral properties of the brain, which had, for millions of years, been biding their time, waiting their turn, began to make their move— the gradual move toward a dominant floral consciousness. When life was a constant struggle between predators, a minute-by-minute battle for survival, reptile consciousness was necessary. When there were seas to be sailed, wild continents to be explored, harsh territory to be settled, agriculture to be mastered, mine shafts to be sunk, civilization to be founded, mammal consciousness was necessary. In its social and familial aspects, it is still necessary, but no longer must it dominate. We need a more relaxed, contemplative, gentle, flexible kind of person, for only he or she can survive (and expedite) this very new system that is upon us. Only he or she can participate in the next evolutionary phase. It has definite spiritual overtones, this floral phase of consciousness. The most intense spiritual experiences all seem to involve the suspension of time. It is the feeling of being outside of time, of being timeless, that is the source of ecstasy in meditation, chanting, hypnosis, and psychedelic drug experiences. Although it is briefer and less lucid, a timeless, egoless state (the ego exists in time, not space) is achieved in sexual orgasm, which is precisely why orgasm feels so good. Even drunks, in their crude, inadequate way, are searching for the timeless time. Alcoholism is an imperfect spiritual longing. In a hundred different ways, we have mastered the art of space. We know a great deal about space. Yet we know pitifully little about time. It seems that only in the mystic state do we master it. The "smell brain"—the memory area of the brain activated by the olfactory nerve—and the "light brain"—the neocortex—are the keys to the mystic state. With immediacy and intensity, smell activates memory, allowing our minds to travel freely in time. The most profound mystical states are ones in which normal mental activity seems suspended in light. In mystic illumination, as at the speed of light, time ceases to exist. With an increased floral consciousness, humans will begin to make full use of their "light brain" and to make more refined and sophisticated use of their "smell brain." We live now in an information technology. Flowers have always lived in an information technology. Flowers gather information all day. At night, they process it. For one thing, information gathered from daily newspapers, soap operas, sales conferences, and coffee Hatches is inferior to information gathered from sunlight. (Since all matter is condensed light, light is the source, the cause of life. Therefore, light is divine. The flowers have a direct line to God. Our own nocturnal processing is part-time work. The information our conscious minds receive during waking hours is processed by our unconscious during so-called "deep sleep." We are in deep sleep only two or three hours a night. For the rest of our sleeping session, the unconscious mind is off duty. It gets bored. It craves recreation. So it plays with the material at hand. In a sense, it plays with itself. It scrambles memories, juggles images, rearranges data, invents scary or titillating stories. This is what we call "dreaming." Some people believe that we process information during dreams. Quite the contrary. A dream is the mind having fun when there is no processing to keep it busy. In the future, when we become more efficient at gathering quality information and when floral consciousness becomes dominant, we will probably sleep longerhours and dream hardly at all. Plants collect odors as well as emit them. The rose may be in an olfactory relationship with the lilac. Another possibility is that between the trees a kind of telepathy is involved. There is also the possibility that all of what we call mental telepathy is olfactory. We don't read another's thoughts, we smell them. We know that schizophrenics can smell antagonism, distrust, desire, etc., on the part of their doctors, visitors, or fellow patients, no matter how well it might be visually or vocally concealed. The olfactory nerve may be small compared to a rabbit's, but it's our largest cranial receptor, nevertheless. Who can guess what "invisible" odors it might detect? As floral consciousness matures, telepathy will no doubt become a common medium of communication. With reptile consciousness, we had hostile confrontation. With mammal consciousness, we had civilized debate. With floral consciousness, we'll have empathetic telepathy. A floral consciousness and a data-based, soft technology are ideally suited for one another. A floral consciousness and a pacifist internationalism are ideally suited for one another. A floral consciousness and an easy, colorful sensuality are ideally suited for one another. (Flowers are more openly sexual than animals. The Tantric concept of converting sensual energy to spiritual energy is a floral ploy.) A floral consciousness and an extraterrestrial exploration program are ideally suited for one another. (Earthlings are blown aloft in silver pods to seed distant planets.) A floral consciousness and an immortalist society are ideally suited suitedfor one another. (Flowers have superior powers of renewal, and thelogevity of trees is celebrated. The floral brain is the organ of eternity.) Lest we fancy that we shall endlesly and effortlessly be as the flowers that bloom in the spring, tra-la, let us bear in mind that reptilian and mammalian energies are still very much with us. Externally and internally. Obviously, there are powerful reptilian forces in the Pentagon and the Kremlin; and in the pulpits of churches, mosques, and synagogues, wheredeathist dogmas of judgment, punishment, self-denial, martyrdom, and afterlife supremacy are preached. But there are also reptilian forces within each individual. Myth is neither fiction nor history. Myths are acted out in our own psyches, and they are repetitive and ongoing. Beowulf, Siegfried, and the other dragon slayers are aspects of our own unconscious minds. At the birth of Christ, the cry resounded through the ancient world, "Great Pan is dead." The animal mind was about to be subdued. Christ's mission was to prepare the way for floral consciousness. In the East, Buddha performs an identical function. It should be emphasized that neither significance of their heroics should be apparent. We dispatched them with their symbolic swords and lances to slay reptile consciousness. The reptile brain is the dragon within us. When, in evolutionary process, it became time to subdue mammalian consciousness, a less violent tactic was called for. Instead of Beowulf with his sword and bow, we manifested Jesus Christ with his message and example. Jesus Christ, whose commandment "Love thy enemy" has proven to be too strong a floral medicine for reptilian types to swallow; Jesus Christ, who continues to point out to job-obsessed mammalians that the lilies of the field have never punched time clocks.) At the birth of Christ, the cry resounded through the ancient world, "Great Pan is dead." The animal mind was about to be subdued. Christ's mission was to prepare the way for floral consciousness. In the East, Buddha performs an identical function. It should be emphasized that neither Christ nor Buddha harbored the slightest antipathy toward Pan. They were merely fulfilling their mytho-evolutionary roles. Christ and Buddha came into our psyches not to deliver us from evil but to deliver us from mammal consciousness. The good versus evil plot has always been bogus. The drama unfolding in the universe—in our psyches—is not good against evil but new against old, or, more precisely, destined against obsolete. Just as the grand old dragon of our reptilian past had to be pierced by the hero's sword to make way for Pan and his randy minions, so Pan himself has had to be rendered weak and ineffectual, has had to be shoved into the background of our ongoing psychic progression. Because Pan is closer to our hearts and our genitals, we shall miss him more than we shall miss the dragon. We shall miss his pipes that drew us, trembling, into the dance of lust and confusion. We shall miss his pranksterish overturning of decorum; the way he caused the blood to heat, the cows to bawl, and the wine to flow. Most of all, perhaps, we shall miss the way he mocked us, with his leer and laughter, when we took our blaze of mammal intellect too seriously. But the old playfellow has to go. We've known for two thousand years that Pan must go. There is little place for Pan's great stink amidst the perfumed illumination of the flowers. When Western artists wished to demonstrate that a person was holy, they painted a ring of light around the divine one's head. Eastern artists painted a more diffused aura. The message was the same. The aura or the halo signified that the light was on in the subject's brain. The neocortex was fully operative. Maybe, as Dr. Dannyboy has postulated, all these things, including disease and our relationship with time, are merely bad habits. If so, an ultimate victory is possible. For individuals, if not for the mass. And maybe evolution—playful, adventurous, unpredictable, infuriatingly slow (by our standards of time) evolution—will rescue us eventually, according to a master plan. To physically overcome death—is that not the goal?—we must think unthinkable thoughts and ask unanswerable questions. Yet we must not lose ourselves in abstract vapors of philosophy. Death has his concrete allies, we must enlist ours. Never underestimate how much assistance, how much satisfaction, how much comfort, how much soul and transcendence there might be in a well-made taco and a cold bottle of beer. Thus, thou must vow upon this day that shouldst thou be living still when these events transpire, that thou wiltst battle them and refuseth prosperity to any immortalist thrust that doth not rise from man's soul and heart as well as his mind. Do promise me now." Alas, because they fight with reason only, making no advance in the area of soul and heart, true immortality wiltst be denied them. If I am truly immortal, I am my own grandchild, my own descendant, my own dynasty."

#tom robbins#jitterbug perfume#wiggs dannyboy#tim leary#floral consciousness#poetry#philosophy#magic#literature

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

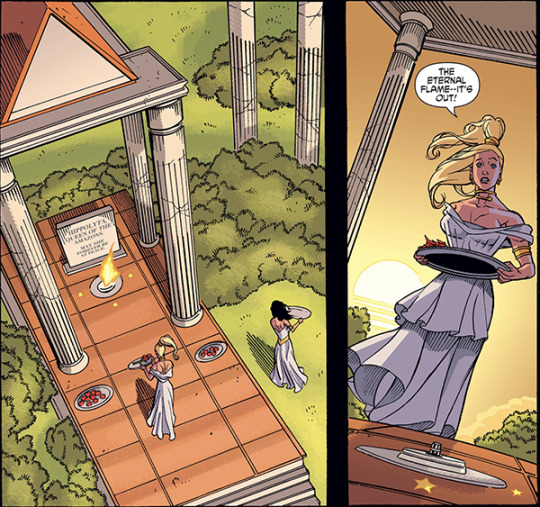

Amazons Attack! - part 3

The story so far: Wonder Woman got a day job doing more or less the same thing she does in her regular job, except in disguise. Circe kidnapped “Diana Prince’s” sexual harasser partner, Tom Tresser, for reasons. Wonder Woman saved him, but was then arrested by the Department of Metahuman Affairs, who located her via a tracking device in a uniform that Tom was blatantly not wearing at any point in the story.

Now Wondy is being held to ransom in a secret bunker, her release contingent on her handing over the schematics to the Amazons’ Purple Death Ray -- a secret she has no access to nor any way of acquiring, as Themyscira is out of reach to all -- and Circe is preparing to resurrect Hippolyta, who doesn’t deserve this shit.

Part 3: Wonder Woman #8 -- Jodi Picoult (writer) and Terry Dodson (artist)

Diana’s still imprisoned in a high-tech cell in some DOMA sub-basement, while her two assigned guards gossip about her.

“Check her out — the chick’s freakin’ nuts!” says Guard #1. Diana is not doing anything particularly nutty. In fact, she’s not doing anything. She’s just sitting in the cell and looking depressed, as one might be after being wrongfully imprisoned, tortured and held to ransom for a WMD. To Guard #1, this is apparently evidence that she thinks she’s better than everyone else.

“She just wants to be free, man,” says Guard #2, and is it just me or do they sound like they’re talking about an agitated whale in a too-small enclosure?

Guard #1 responds with an incoherent ramble about how nobody in society is free, and we’ve all gotta work to pay the damn bills and go home to our wives every damn night, so “that crazy broad” had just better come to terms with the fact that she’s no better than the rest of us. Guard #1 clearly has some issues of his own to work through.

In Themyscira, Circe has exhumed Hippolyta’s corpse and resurrected her. All the Amazons are shocked and confused, despite the fact that they all saw Circe arrive at Hippolyta’s grave last issue and obliquely announce that she was going to restore Polly to life. So basically the rest of that last issue’s encounter went like…

Circe tells the Amazons that Diana has been imprisoned by the US government.

The audience is informed that, for this performance of “Amazons Attack!”, the role of Hippolyta will be played by a bloodthirsty, irrational man-hating harpy.

“It is always the same with the world of Man. What they don’t understand, they fear. And what they fear, the try to tame. To them, my daughter is the enemy… and enemies must be crushed. If it is war that they want… it’s war they will get.”

More clumsy wording here: When Polly says “enemies must be crushed”, she’s clearly referring to the Americans. But the previous sentence identifies Diana as “the [Americans’] enemy”, making it… kinda sound like she’s saying Diana must be crushed.

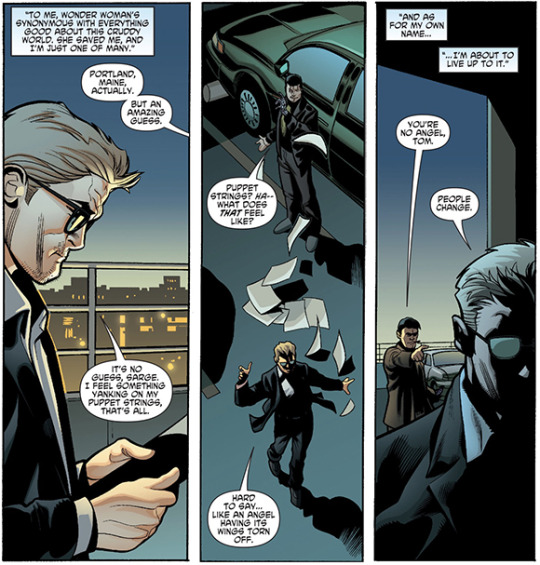

Tom, for some reason, has decided to return to the wannabe villains bar from last issue — this time to have a drink and complain to the bartender about how shit his partner is. Diana isn’t answering his phone calls, and Tom complains that “she probably can’t figure out how”.

How did they even pitch this guy as Diana’s new love interest? ‘He’s a complainy misogynist, she’s Wonder Woman in disguise! Together, they fight crime!’

Tom is called back into work. Even though the Department of Metahuman Affairs has plenty of perfectly serviceable offices and meeting rooms, he meets Steel in a deserted parking lot under the cover of darkness, as though he’s bloody Deep Throat or something. He’s even wearing sunglasses. In the middle of the night.

Steel tells him that the Wonder Woman case is closed, it’s out of DOMA’s hands, and the reason Tom hasn’t been able to contact his partner is that she’s been reassigned. Which, btw, so has Tom. He’s expected in Maine tomorrow.

Despite Tom’s well-evidenced lack of basic deductive skills, he manages to peg that something a little weird is going on here. Some particularly overwrought dialogue ensues.

Tom: I feel something yanking on my puppet strings, that’s all. Steel: Puppet strings? Ha— what does that feel like? Tom: Hard to say… Like an angel having its wings torn off. Steel: You’re no angel, Tom. Tom: People change.

Throughout this two-page scene, Tom delivers a voiceover in narration boxes. There’s no good reason that this should be here. It’s an abrupt and slightly jarring inclusion — the only narration boxes up till this point have been Diana’s — and the only narrative function it serves is to cover for the shortcomings of Picoult’s scripting by outright stating Tom’s motivations and feelings towards Diana.

They call me Nemesis. As I���ve recently been reminded, my name means ‘enemy’… […] but in naming Wonder Woman the ‘enemy’, they’ve crossed the line. To me, Wonder Woman’s synonymous with everything good about this cruddy world. She saved me, and I’m just one of many. And as for my own name… I’m about to live up to it.

Basically, Tom believes Wondy is synonymous with all that is good, and this is the driving factor that leads him to turn on his boss and colleagues and side with a supposed enemy of the state.

This seems like a good time for a quick review of Tom’s complete history of interactions with and conversations about Wonder Woman up to this point.

Complained about missing a chance to see Wonder Woman in the flesh because “I bet she looked hot”

Bought a Wonder Woman action figure to masturbate to give to his possibly-fictional “niece”

Acknowledged that Wonder Woman was a hero, but that it didn’t matter whether she’d done anything wrong because “it’s our job” to arrest her

Upon meeting Wonder Woman, peppered her with wildly inappropriate, objectifying remarks, including describing his sex dreams about her, speculating on what it would be like to fuck her in mid-air and asking her about her sex life

Told Wonder Woman he wished he could work with her instead of his shitty partner, who is secretly Wonder Woman

Throughout the first two issues, Tom treats Wondy primarily as an object of lust. There’s a recognition of the good she does, but he’s more interested in her banging body than anything else. The one compliment he does pay her is an unwitting insult, because it’s tied to his largely irrational hatred of her alter ego. He loves the sexual fantasy of Wonder Woman, but can’t stand the bespectacled, pant-suit-wearing Diana Prince (especially when she dares bark out orders).

So this deep admiration for Wondy as a force for good in an ugly world — this belief that will drive all of his actions in this story going forward — has come completely out of the blue. It’s introduced only in the precise moment when Tom first decides to act on it. That is shitty, shitty writing.

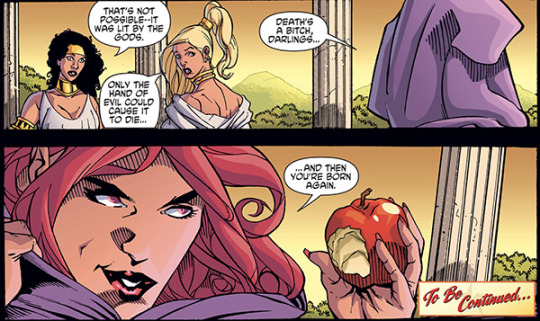

Circe drops into Diana’s cell for a quick ‘you’re not so different, you and I’.

“You just don’t see how similar we are. Humans are afraid of us. We’re outsiders — we’re powerful women — and what we fight for is hidden beneath the blood on our hands.”

So, you fight for… your… hands? Your skin? Your… fingernails…? What—

Okay, no, I think what she’s trying to say is that people don’t see the lives Diana’s saved, only the bodies she’s left in her wake. Which, dude. Come on. You’re an evil sorceress who’s razed entire kingdoms and turns people into animals for funsies, but Diana snaps one measly neck and suddenly you’re calling her Lady Macbeth?

(yes, really.)

Circe says they’re both fighting for what they love. Then she immediately contradicts herself and says that only she is fighting for what she loves -- no matter what it takes -- whereas Diana is only fighting for good out of a sense of general obligation to be good.

Diana says that there is such thing as Right and Wrong, and that these things are distinct and immovable concepts, and that on its own makes me want to set this whole damn comic on fire, but then Circe takes it upon herself to give Diana a primer in moral relativism. Circe. Fucking Circe has a more thoughtful and nuanced understanding of ethics and morality in this book than Wonder Woman, what the flipping friggity fuck.

Circe says that it was once considered moral to own slaves, and “what’s considered right today could be wrong tomorrow”; Diana is skeptical.

Circe ends, as incomprehensibly as she began, by declaring that “love and murder are the only things that matter. They’re what it means to be human”, and therefore she will always be more human than Diana.

Tom uses his vaguely-defined master-of-disguise technology to impersonate Sarge Steel and break Diana out of her cell. She doesn’t trust him, since the last time the last time she saw him he was being congratulated for helping to apprehend Wonder Woman. Despite the fact that these congratulations were accompanied by a look of shock on Tom’s face and the revelation that he’d been tracked without his knowledge through a locator chip in a uniform he was not currently wearing -- something Diana also witnessed.

But, see, she has to be mad at him, because otherwise we couldn’t get that good old stock standard ‘here’s your lasso - ask me anything’/‘nah, I guess I’ll just trust you instead’ scene.

Armed DOMA agents arrive on the scene, and Diana does what we’ve all been wanting to do since Tom Tresser first stepped into this comic.

Diana: Tom, listen… Tom: You don’t have to say it… I know you must really love me right now. [Diana decks him]

It’s a fakeout, of course, so that when she escapes with him in tow, he looks like a hostage rather than a willing accomplice.

Speaking of escape — Diana’s free of her cell, but she’s still a good hundred feet beneath the earth in a secure bunker, with hundreds of DOMA agents between her and the exit. Fighting her way out of this one’s going to be a real—

—oh.

Or she could just punch her way through a hundred feet of solid rock, I guess.

Meanwhile:

The Amazons throw spears and shoot flaming arrows at things, and the biggest military force in the world pisses its pants at this terrifying display of Bronze Age weaponry. Nothing in the extensive training and experience of these elite fighting men and women has ever equipped them to deal with the horrors of women with pointy sticks!

“We’re no match for their firepower! We need help down here!”

Steel calls in the JLA and Circe swans around gloating because, gasp, the two of them are working together.

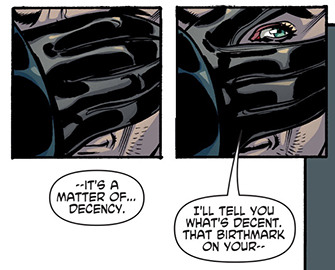

Diana’s reached the sewers. Tom has come to and, naturally, he’s found something to complain about — namely, the fact that she punched him.

Diana’s costume is pretty ripped up, so she asks Tom if he has a sewing kit. Because even though she’s just been illegally imprisoned, tortured and held to ransom by somebody claiming to answer to the President of the United States — somebody who, even now, is sending dozens of agents out after her — modesty is her first priority. Really.

All Tom has is some epoxy adhesive. Diana, evidently deciding that the risk of severely burning herself is preferable to the risk of exposing some skin, decides to use the epoxy to mend her costume while she’s still wearing it. But first, she asks Tom to close his eyes.

We’ve all seen some version of this scene before. You know what happens next.

Diana: Your eyes are closed, right? Tom: Uh… right. Clearly you Amazons have a lot to be insecure about aesthetically. Diana: It’s not a matter of insecurity… It’s a matter of… decency. Tom: [ogling her] I’ll tell you what’s decent. That birthmark on your— Diana: You’re a pig, you know that?! Tom: Well, you, coincidentally, are a pain in the same place you’ve got that birthmark!

Gee, I’m glad Tom Tresser thinks Wonder Woman is the lone bastion of goodness in the world. I’d hate to see how he’d treat a woman he didn’t respect so highly.

The argument is interrupted by an explosion, which of course results in Diana throwing Tom out of the way and…

A second ago they were having an argument sparked by Tom yet again disrespecting her personal boundaries and treating her like a sex object, and now suddenly she’s super turned on. Wonderful.

They decide to investigate the explosion. Flying out of the sewers, they find the city on fire and the Lincoln Memorial in ruins. And standing at the centre of the rubble is, of course, Hippolyta.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

A gem of a movie that misses its mark is “The Miracle” from 1959.

At this time of year with Passover and Easter, seasonal favorites to watch have been the traditional ‘sword and sandal’ movies like ‘Ben Hur’ and ‘The Robe.’

Interestingly when these types of movies were made (which was right after World War II) in that time there were lots of movies with religious or semi religious themes.

Some historians believe that this was because after World War II people had a sense of gratitude for the end of the war.

In the 40s through the 50s and into the early 60s ‘sword and sandal’ - biblical or religious-themed movies were well received.

Among the most notable are epics like ‘The Ten Commandments,’ ‘The Robe’ and ‘Ben-Hur.’

One movie that debuted in 1959, in which all the elements of a religious or semi-religous epic was utilized was called ‘The Miracle,’ starring Carroll Baker and a then, very-young Roger Moore.

To this reporter, it is a gem of a movie. Yet it is under appreciated because as some film historians and critics point out, it was released just after ‘Ben- Hur.’

While ‘The Miracle’ lends itself to a well produced epic, the movie falls short in its lack of ability to emphasize a clear and well punctuated theme.

This reporter noticed immediately that even with its fine cinematography and wonderful costume and set design, it gets convoluted. It is extremely sweeping and alludes to a complexity that as I see it should be explained even if just a bit more, to an eager audience.

The issue here is that it’s main objective or so it seems is to describe the distinction between romantic love and mystical love.

For those who are not Catholic it’s hard to follow. But even those that are Catholic it takes a well-read and devout person, to understand the subtle and yet, complex lines within the story.

Initially it is about the young aspirant to the convent, Teresa. This Teresa of the story is loosely based upon Teresa of Avila. Teresa of Avila was A 16th century mystic in Spain.

While the time frame of the movie is set somewhere within the Napoleonic era it is not really clear which year the events of the movie take place.

Also, it is not clear exactly which religious order this Teresa is an aspirant to. It seems at first to be Franciscan, because the opening scene is for the blessing of the animals. The nuns are dressed in what appears to be a brown and white habit. But upon closer view, the brown scapular or apron which Carmelites wear is more mauve than a traditional Franciscan brown or gray habit that a Franciscan would wear.

Actually it doesn’t matter which order, but a clearer reference does help. Especially when trying to convey the mystical aspects. Each religious order has a mystical tradition.

The convent is in the fictional valley of Miraflores, somewhere outside of Madrid but the script never says exactly where. From this reporter’s point of view, the story seems real but isn’t.

The audience is being lead into some form of historical fiction, which is okay. But some clarity should have been stated.

Are the nuns cloistered? Or do they have contact with people? Again, are they Franciscan, or Carmelite? Elements of these traditions are implied. Yet It is never really stated.

Historically the Franciscans, the Carmelites and the Dominicans played a very vital if not domineering role in the religious culture of Spain. This Spanish culture made its way to the New World. And, then to the United States via the California Missions and the Pacific South West region.

Parallels between the Teresa in the story and Teresa of Avila in real life are very obvious to see; especially to a Catholic audience. But to an audience not familiar with that it’s hard to follow.

In the opening credits there is mention of a “Divine Mercy.” But the script (which includes dialog between characters, etc) does not state this clearly enough. Nor does it do so through action.

Carroll Baker who portrays the young aspirant/postulant Teresa does provide youthful emotion conveying a relationship with the spiritual that at times it is charming and convincing. But it then goes over to the melodramatic.

The scene where she speaks aloud to Blessed Mother Mary depicted in the statue in the church with the tile of “our lady of Miraflores” is tender. With prayerful expressions like “oh Mother Mary the only mother I have known,” the script does convey her affection for the life of the convent and the fact that she was raised by the nuns, having been left at their doorstep. This is sweet.

And, the fact that as a young woman she is drawn to the romantic and ultimately to the world is also nicely and accurately portrayed. Mother Superior, graciously understands this as she too read Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’ as a young girl of 17, “under different circumstances, of course.”

Teresa’s love of music, poetry and literature adds to her humanity amid the convent atmosphere and its dedication to “perfection and the holy rule of the religious order.”

A gust of wind also seems to have a role in this movie. But it is never really demonstrated clearly as to what it means. When a gust of wind occurs, change happens.

Is this a symbol of the mystical? The script and the action between characters never says for sure.

Like ‘Ben-Hur’ and other historical fiction stories, ‘The Miracle’ is based upon a previous film done in the silent film era. And it goes back to even an earlier version upon the stage by Karl Vollmoller, which he seems to have obtained from old European passion play type stories and legends of Medieval times.

The fact that the outline of this story was done previously long ago, tells why the $3.5 million dollar production is so well-made. Cinematography, the movie is outstanding and the list of actors/actresses to fill a cast of over 91 people is impressive.

But again, it is this vagueness and sweeping references that misses an important mark in story-telling.

The tyrant Napoleon has caused British troops to make their way to Spain to push the French and Napoleon’s egocentric forces back in their place. As a battalion of British soldiers stop at the convent to get water, Teresa catches the eye of a young officer, Michael Stuart, played by Roger Moore.

Baker’s simply beauty and Moore’s dashing charm are delightful to behold. Her distinctive voice and his elegant British accent are easy to listen to and the script adapted/written by Jean Rouverol and Frank Bulter serves them well. Together - Baker and Moore make the ideal couple for any paperback novel romance.

More than just a stop for water brings them together. He is then wounded in battle with Napoleon’s forces and is back at the convent to be nursed to health by...you guessed it, Teresa.

Yet, it is that “unseen” mystical element - that is an obstacle to their union. The conflict within Teresa between the romantic love she has for Michael and the mystical love she is believes in, is obvious.

Her prayers for his safe return to Devon, England his home go with him as she stands firm on the belief in this “mystical” or “Divine” love.

Yet, when romantic love takes hold, she rushes out to see him one last time in a gust of wind. Only to return to the convent chapel asking Our Lady of Miraflores to “show me a sign!”

As Teresa prostrates herself on the stone floor of the chapel, asking for guidance a gust of wind stirs the skies to rain and disrobing her nun-like attire, Teresa ventures out into the storm to find Michael at the inn in the village town, waiting for her.

But as she reaches the town, it is under siege by Napoleon’s men. Searching for Michael amid the chaos, she stumbles into a French soldier with lust on his mind. As he proceeds to have his way with Teresa, a gypsy woman appears.

She saves Teresa from a terrible outcome in the arms of the brute and brings her to the gypsy camp in the hills above the valley.

Right from the opening scene when the blessing of the animals takes place at the start of the movie, gypsies are present. They seem to symbolize the outside world and those on the fringes of a tightly-knit society.

Actor, Walter Slezak is among the principal characters in the gypsy encampment. He provides not only integrity to the plight of the outcasts but a sense of humor and sharp wit.

Teresa’s determination to find her beloved Michael is dashed when she learns from two of the gypsies that “an English officer was killed.” And, that his fine pocket watch (which Michael had shown to her while recuperating at the convent) was among the loot the gypsies had taken from the dead soldiers.

Angry, upset and seemingly confused, Teresa denounces her faith, exclaiming “I am not a Christian!”

Tattered and dusty, Teresa then finds herself between two brothers, rivaling for not only for stolen loot but also their mother’s love. The contrast between the earthy, bombastic, live-flesh and blood gypsy mother and the lofty Blessed Mary in the statue of Our Lady of Miraflores is striking. Especially, when the gypsy mother role is played by Katina Paxinou.

Her performance is electrifying as she is the type of actress who as one might say, “eats up the scenery.” Just her mere presence in the film without any dialog speaks volumes.

Why she favors Guido over Carlito is not understood. Yet, she knows the naive Teresa is folly for her sons. And Guido wins the affection of a reluctant Teresa as he convinces her to marry him, albeit sort-notice. Her faith no longer as strong she agrees.

Only, indadvertedly, Carlito’s jealousy brings the French to the gypsy camp to take his brother Guido away. Sadly, in Carlito’s short-sightedness he exposes the entire camp to danger and the vengeful French troops open fire on the people there.

Guido is killed and Carlito is given a bag of gold as reward for Guido’s whereabouts as a wanted man. This then spurs the gypsy mother to disown her remaining son by shooting him on the spot.

This distresses Teresa as she runs away from the gypsy camp and luckily finds help in the unlikely but shrewd gypsy Flaco, played by Slezak. Seeing her potential as a money-maker with Teresa’s gift of song and dance, they travel to Madrid.

There she meets a handsome matador and then a kindly old gentleman-aristocrate who help Teresa and Flaco gain access to the stage as “Miraflores - the Gypsy dancer and singer.”

What irks me most, is the fact that the script doesn’t really explain or try to illustrate the distinctions this young woman is making on a “spiritual journey” of sorts.