#but either for what i consider morally *illegitimate* reasons. or an illegitimate reaction to legitimate reasons (like the Rsd Rage Response

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

oh

#re post earlier. i had kind of a gut reaction that 'no these are two different flavors of Bitey Dangerous and Sort of Uncontrollable#as self conception. and they need to be treated as separate'#and i think. like. a lot of it is the one i embrace is 'that sort of mindset and i-am-going-to-snap-dont-test-me as a response to#what i consider to be having been pushed too far by *legitimate* reasons--boundary violation trauma interpersonal betrayal'--#which is also like. if youre nice or affectionate to me in that mood im likely to react positively if weirdly#its often uncomfortable and potentially destructive but its a. feels morally legitimate and b. something that can be worked with#(and c. i can honestly enjoy it for aforementioned 'will react positively to kindness' reasons. 'world destroying pseudogod need pets' is.#a very fun emotion to have ngl.)#the other one--what i earlier tonight called the megatron persona(tm) due to similarities to my general read on tfp megatron#(which for the record i am reasonably certain is like. legit and based on textual support. and not projection. insofar as theres any#projection going on there it *followed* the initial few rounds of character analysis and was like '...oh. same. i hope i dont act like that#about it.') that state of mind is deeply centered around my feelings going out of fucking control in a similarish direction#but either for what i consider morally *illegitimate* reasons. or an illegitimate reaction to legitimate reasons (like the Rsd Rage Response#fear of rejection; betrayal (where if i was being rational i wouldnt see one); anger over insult re things i KNOW werent insults#and primarily just. that state of mind. it gets into 'i cannot bear being hurt so i will try to force people to stop hurting me' real fast#and that gets nasty. and im not sure that being nice to me in that state works or does any good#someone directly involved i think maybe should just force a disengage for a while rather than that; someone not directly involved can maybe#calm me down like that but again thats by forcing a shift or disengage not a Fun Version of the same emotion#hence why like. this isnt supposed to happen. but if im relapsing other stuff its best to maybe have an understanding of how to stop it#delete later#txt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

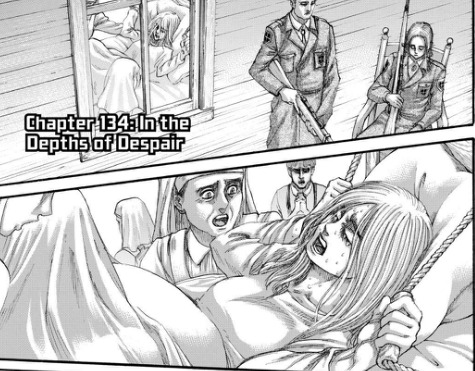

SNK 134 Review

Thank you. Thank you so much. This means so much to me.

(Ofc this chapter is called “In the Depths of Despair.”)

Sigh.

So, I guess I have to have an opinion on this chapter now.

For a while there, it looked like SNK had made the right choice.

Eren was the asshole. He was insubordinate, ungrateful, uncooperative, and above all else, a fucking sociopath. Cool, got it. One and done.

But then his friends started talking about how it was really their fault he’s doing this.

Ok, that’s fine. They’re desperate to stop him, so they’re just saying whatever they think will ingratiate themselves with Eren and help talk him down. Dynamics like that are very common in abusive relationships.

Now we arrive at this chapter, where even random people are saying Eren is a victim *as he is murdering them!*

It is patently absurd that Eren is having a warranted or natural or reasonable reaction to what he’s been through.

If Eren were a better person, he would have known that mass murder against the Eldians was wrong because mass murder is wrong. Unfortunately, Eren is a fundamentally amoral person. The only moral compass he has to guide him is a childish belief in “you hit me, so I get to hit you.”

He’s said as much on multiple occasions. He has said, “If someone tries to take my freedom away, I will take their freedom away.”

Instead of being the better man and ending the killing, his solution was to kill more people than them, faster and on a larger scale.

I think the clearest picture of Eren’s worldview was given when he spoke to Historia. He said the only way to end the cycle of violence was to destroy the whole world.

That is Eren’s deeply felt belief: there can be no peace or coexistence; the only way to win is to be the last man standing.

This mindset is so natural to him that he will even kill his friends for opposing him.

He told them that they were free to oppose him, and he was free to fight back. That’s how he justifies killing them to himself. They have the choice to oppose him, so if he fights back and kills them, it’s their fault they died, not his, because they could have made the choice to flee and live, but decided to stand and die.

In reality, the alliance is fulfilling a moral duty to protect life, while Eren is an asshole who has killed billions.

The series wasn’t kind to Eren about that. He was depicted as a cheering child as he murdered everyone. The Rumbling was not white washed either. The take away was obviously that Eren’s decision was not the product of a sound mind.

And yet.

Now I have to wonder if the series is seriously trying to say the Rumbling embodies some form of justice.

There are multiple layers to this issue, so let’s start at the surface level.

So in what is obviously a ham-fisted attempt by Isayama to lecture the audience about morality, a Random Commander Guy filibusters about the ills cast by the Marleyans on the Eldians and how this has rebounded back at them.

It is generally considered good writing for characters to get their just desserts. If someone sells drugs to kids, you expect something bad to happen to them. If someone helps a kid cross the street, you expect something good to happen to them.

What’s different between a generic case of just desserts in a story and this chapter in SNK is that the dessert is typically delivered through some nebulous, karmic force, rather than a vengeful twerp with God-like powers.

When the drug dealer’s car blows up, it’s karmic fate, not revenge.

The car doesn’t blow up because one of the kids devoted his life to exacting revenge, it’s because the car just blows up for no reason, or because something completely unrelated to the dealer causes a bomb to be planted in the car, or the dealer brought it on themselves by getting caught up with terrorists.

People may or may not deserve to suffer, but it’s fine to show people suffering if you’re just trying to make a point about how people should act.

Eren’s a different case. For several reasons.

To help untangle why, let’s think about the death penalty.

The death penalty is an example of retributive justice. Put simply, it’s the idea that retribution can be morally just.

The Rumbling is immoral precisely because it is something a supporter of retributive justice would emphatically NOT support.

Most supporters of the death penalty would justify it as an act by a legitimate societal authority. Eren is not that.

Eren is not an authority figure. He does not speak for the Eldian people and has no right to exact this genocide on their behalf. No one made him King of the Eldians. It’s not his place to decide what’s in the Eldian’s best interest.

Also, killing people because “it’s what the scumbag deserves” is usually justified because it’s a sentence for a crime handed down in a legal process.

Rights can be taken away, but not arbitrarily. Transparency is an important part of this. Acts that are a crime are public knowledge, as well as the prescribed punishments. The criminal law is also supposed to apply to everyone equally, not selectively. To say nothing of the law itself being duly enacted by a legitimate governmental authority.

The same principles apply to the process by which a right is taken away. The process must be laid out in a law that was duly enacted by a legitimate government authority, applies to everyone, and is publicly known.

Eren’s process, of *fucking* course, is nothing like this. Eren has no legitimate authority. He’s a Guy With an Opinion who bumbled into attaining absolute power, and now he’s acting on that Opinion.

He not the government punishing a convict. He’s a guy with a gun shooting people he doesn’t like. The Rumbling is not just retribution, it’s just murder.

Commander Guy says that if they knew this would happen, they would have acted differently.

That’s a good point.

Why the fuck do they deserve to die, then?

To some extent, everyone’s worse impulses are kept in check by the knowledge that there will be consequences if they act rashly.

But it’s not just that.

Laws are public knowledge for a reason: it’s fair. If you know your act is a crime and that performing said act will result in a certain punishment, then by committing the act anyway you have tacitly accepted whatever punishment will be meted out.

The moral onus is placed on you.

This is why knowledge that you are committing a crime is necessary to be convicted of a crime.

In principle, the case with the Marleyans is the same. Is it fair to punish someone for an act they did not know would carry that punishment? No.

They may know the act was immoral, but that is not the same thing as knowing it will lead directly to their death.

And needless to say, but you only deserve to be punished for an act if you deserve to be punished for that act. The Marleyans do not deserve to be punished for that act.

There are multiple ways a wrong can be righted. There are punitive ways, in which the perpetrator is harmed outright. There are also restorative ways, in which the victim is compensated for the harm done to them, usually at the expense of the perpetrator.

I have already explained why Eren lacks the authority to pass judgement on the world, and that the process by which he made his decision was completely illegitimate, but it needs to be said that this punishment is totally improper in itself.

Wiping out humanity is purely punitive. To use the obvious analogy, I don’t think any sane person would argue white people deserve to be punished for racism. Supporters of racial justice usually talk about restorative, rather than punitive, forms of justice, like reparations.

The Rumbling does not make the Eldians whole again. It does not restore their trampled dignity. It is purely an act of vengeance.

Casting it as some kind of deserving retribution is crazy.

Oh, and, you know, suffering is bad, so retributive justice is wrong even disregarding everything I just said.

You could theoretically believe life is a miracle, but that people forfeit that right if they act wrongly…it’s not something many people would support.

If Dino!Eren had been depicted as a random force of nature that visited ruination upon humanity, we could have potentially gotten a good story about how hatred leads to no good outcomes. Like how Godzilla is a metaphor for the ills of nuclear weapons.

Instead we get a nihilistic tale about two sides punching each other until one keels over dead. And somehow the one that keels over deserved it.

What makes it nihilistic is that you could easily reverse it. What if right before Eren destroys Fort Salta, aliens invade the Earth and help the Marleyans.

Now the Eldians are on the verge of annihilation and *Eldian* Commander Guy gets his turn to say “Woe is us who surrendered to hate. We deserve this.”

There is no right side or wrong side. No deserving side or innocent side. The Eldians were cheering for genocide the same as the Marleyans. The difference is the Eldians had a God on their side.

The morality of this series is just all over the place.

The Alliance and Eren are equally sinful, but now Eren is an agent of karmic destiny and his victims “deserve it.”

There isn’t much to talk about this chapter besides that.

Armin still hopes to take Eren alive, but good luck with that.

Eren can manifest other titans from his body, which is cool I guess, though it’s pretty clear this power only exists to give the Alliance things to fight.

There were a lot of allusions to parenthood this chapter. The baby and the cliff. Reiner’s mom realizing how shitty she’s been. Historia’s pregnancy. The Commander Guy saying it’s the fault of “us adults.” The numerous shots emphasizing the kids at Fort Salta.

Child abuse is a common theme of SNK. And not just parental abuse, but societal abuse, too. Children are the victims of individual foibles and broader social ills, like racism and police brutality.

The cycle of violence at the heart of the series’ conflict is bad for everyone, but the story emphasizes that it is bad for children in particular. It harms them, and leads to a world that is worse off for them.

If there’s one takeaway from SNK, it’s that we should think of the children. Adults shouldn’t just take care of their kids, they should fix broader social issues, if not for themselves then for the children’s sake.

It’s a fucking insult.

Historia’s pregnancy is all but confirmed here. There’s no way it’s fake. There may have been motive to fake being pregnant, but there is no fucking way she’d have a reason to fake *birth*.

I always leaned towards the pregnancy being real, so that didn’t get to me. What gets me is that Historia is just…there. On Paradis. On the sidelines.

Not only was Historia, who is the only likable female character in this show now, impregnated, she’s also been MIA most the last two story arcs.

I had thought Isayama was saving her for the finale. Surely, Isayama understands that if you sideline a major character for no reason, they have to come into play at some point, I thought. Surely.

Characters are tools; they exist to be used. So use them.

But no, it seems Historia is legit not going to be a thing in this final battle. My dreams of the domineering boss saving the day are dashed.

But what really messes with me is how shafted Historia has been since basically the end of the Uprising Arc.

Historia’s only contribution to the plot after Uprising, but before the pregnancy was making the disastrous decision to make the truth of the world public, which paved the way for Paradis society to become radicalized and back Eren’s coup.

She has done nothing other than that.

Obviously her pregnancy will have thematic importance, but at this point the best Historia stans can hope for is that she’s the main character in the epilogue.

I’ve always assumed the pregnancy was the product of a loving relationship. For all his incompetence with Historia, I was willing to assume Isayama would not force her to carry a forcibly impregnated child to term.

And you know that even if the child is the product of rape, Historia will still have to say she loves and accepts them as her child and will raise them lovingly, with no regard or acknowledgement of the trauma of having to raise a child born out of her being raped.

Because the theme of the story.

All life is a miracle.

All children deserve to be loved.

Even if it was rape.

Except it’s more complicated than that, and I’m terrified to think that Isayama may not understand that.

So for now, I choose to presume that Historia is pregnant because she loves someone, decided to have a family with them, and we’re being led to believe she was raped for shock value.

But arguably more important is what this means for the queer audience.

Historia’s first love interest was another woman.

She’s queer. A lesbian. A dyke. What have you.

Now you’re telling me she either loves a man, or was not only raped, but has to love and accept the child that results from that trauma?

And for what?

So we can end the manga on a speech by Historia moralizing about the value of posterity?

Historia stands at the nexus of two subjects in this manga: the value of posterity and the denigration of queer people.

It is very homophobic of this series to pair a queer character with a dude to affirm a message about the value of children and motherhood.

As if queer people can’t have children.

We seem to be headed down that path.

It didn’t have to be like this.

Queer people can have children through artificial insemination. And artificial insemination is conceivable with Paradis’ current level of technological development.

Isayama is choosing to do this because queer people are not a part of his vision of a world where people, especially children, are able to live free.

That’s very sad, because it shows how empty SNK’s morals are.

So who’s the slave here?

Who here is truly free?

The ones who are free are the ones who aren’t reading Attack on Titan anymore.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘The developing action of Act 2 can be seen as a struggle between good and evil characters. Whilst to some extent the ‘good’ characters bring their problems on themselves, there can be no justification for the actions of the ‘evil’ characters.’

It is hard to deny that Act 2 of ‘King Lear’ can be interpreted as a struggle between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ characters, as much of the developing action is devoted to the ‘evil’ characters schemes prevailing, leading to the downfall of each ‘good’ character. For instance the act opens with a scene between Edmund and Edgar discussing their father’s arrival. The exchange takes place at night creating a pathetic fallacy for Edmund’s dark intentions, and Edmund’s heavily punctuated speech, “He’s coming hither now, I’th’night, I’th’haste”, creates short, sharp statements which allow Edgar no time to question or answer back, his only response being a half line “ I am sure on’t, not a word.” In the scene Edgar is fooled by Edmund into thinking his father is coming so he must run away, many critics believe Edgar is too easily fooled, however this could be a comment on just how easily the ‘evil’ characters can gain influence and could possibly act as a warning to the characters in the main plot. Gloucester then enters and is unknowingly mocked by Edmund as he curses his loyal son Edgar after being fooled by Edmund’s scheming. There is irony in Gloucester’s words as he calls Edgar an “unpossessing bastard”. The struggle between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ worsens as Regan and Cornwall join Edmund, leaving Gloucester isolated from any other ‘good’ characters, saying little and being vulnerable. This is possibly another example of Shakespeare using the sub-plot to compliment the main plot as Lear finds himself in a similar situation later in the act. In the next scene, we see an violent argument between Lear’s loyal servant Kent, still in disguise, and Goneril’s lackey Oswald. Shakespeare highlights their opposing loyalties, having Kent call Oswald a “lily livered” sychophrant. In many ways Kent can be seen as a symbol for the “old order” which critics believe is “under threat in this world of increasing madness and selfishness.” This could be said of all the ‘good’ characters in the play, they are honest and traditional, shown by their belief in the stars and heavens, yet are constantly outwitted by the sly and scheming ‘evil’ characters. Scene 3 is yet another instance of Shakespeare weaving the main plot and sub-plot together, here Edgar talks about how he must strip himself of all possessions and disguise himself as a ‘bedlam beggar’, a mad man, in order to escape his father. This mirrors the stripping down of Lear’s following in the next scene, showing both characters’ loss of power, which allows their humanity to be explored. In the final scene of Act 2, Lear finds Kent in the stocks and is, just as Gloucester was before, slowly surrounded by the ‘evil’ characters. In this scene when Lear is finally allowed to speak to Regan, he shows vulnerability claiming Goneril has “tied sharp-toothed unkindness” to his heart. However Regan is cold in her response, calling him “sir” in place of “father” and finally taking Goneril by the hand, revealing her true loyalties at Lear’s expense. On the other hand, arguments can be made that Act 2 is not about the struggle between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ characters, and is instead about disguises, many characters are in disguises, such as Kent and Edgar, or need to learn how to disguise their feelings, like Lear. Shakespeare uses disguises to explore topics such as madness, social niceties and the distribution of wealth in contemporary times. Another argument about Act 2 being about the struggle between the two archetypes is that by the end of the scene the ‘evil’ characters are sheltered from the storm, they aren’t being punished by it, they have essentially won. It could even be argued that there was no ‘struggle’ at all, many of the good characters brought about their own suffering.

The strongest example of ‘King Lear’s protagonists causing their own suffering is Lear himself, who sparked this disloyalty in his own daughters by pitting them against each other in the love test, which can be seen as an unnecessary stroking of Lear’s own ego at the expense of fairness. Another factor that causes Lear suffering is his rashness, which often leads him to alienate an ally to create an enemy. Regan and Goneril are obvious examples but Kent and Cordelia are exceptions, this could be seen once again as reflective of the new and old order, respectively. Lear also causes his own struggle with his inability to let go of his power. This causes his daughters to consider him a threat and is what eventually leads him to be stranded on the heath in the raging storm. Another example of Lear being responsible for his own suffering would be his blindness to the situation. This is most obvious when Lear shows shock at Regan’s alignment with Goneril, “O Regan! Will you take her by the hand?” This line shows that Lear has been blind to his daughters scheming, presenting him as unobservant to the audience, who have seen this coming. This inability to see the truth is shared by many ‘good’ characters, such as Edgar and Gloucester who are blind to Edmund’s plotting against them. Another quality that leads ‘good’ characters to cause problems for themselves is their loyalty, particularly in the case of Kent and the Fool, who choose to stay with Lear after his loss of power. This choice leads them to be wandering the heath in the storm, their lives in danger. However, this makes the characters more sympathetic, we come to trust them and admire their loyalty to Lear. Kent is also unable to hide his true opinions; “His countenance likes me not” is representative of this in scene 2. This statement is what lands him in the stocks. This problem is also shared by Cordelia who is banished for refusing to lie to her father in the love test. Gloucester is another character that could be interpreted as causing his own problems. Edmund, his bastard son, is scheming against him because he has been treated badly by his father who acts as if he is ashamed of him and refuses to share his legitimate son’s inheritance with him. This point is actually somewhat debatable as a contemporary audience wouldn’t find fault in Gloucester’s behavior, however one thing that cannot be disputed is his fickleness as demonstrated in lines 55-79, in which he calls Edgar, his ‘good’ son, a “murderous coward” and claims “I never got him.” This reflects Lear’s rashness and tendency to ostracize the wrong child. The final way in which ‘good’ characters could be seen as responsible for their own troubles is their belief in the stars and heavens. This is a sharp contrast to ‘evil’ characters such as Edmund who believes in creating his own destiny, in many ways this can be interpreted as bad because the character actually knows he is doing something bad, but does it anyway for his own gain.

There are many instances in ‘King Lear’ where there are no justifications for the ‘evil’ characters’ actions, such as how Goneril and Regan lie to their father about how much they love him in order to get more land. Many of the ‘evil’ characters are quick thinking and lie easily, making them Machiavellian - an archetypal evil character. To a contemporary audience Edgar’s actions would be unjustifiable; he was born a bastard and is treated accordingly, so they would not sympathize with him. This is different for a modern audience who care less about parentage. This is applicable to many of the ‘evil’ characters, contemporary audience would have been shocked or horrified by their actions but modern audiences understand their mistreatment and can sympathize with their actions. Another way that determines whether the ‘evil’ characters’ actions can be justified is the staging of the play. Goneril and Regan can be portrayed as paranoid and power hungry when stripping Lear of his men if the audience doesn’t see them causing trouble or being loud and obnoxious or can be seen as reasonable if his men are on stage causing trouble and taking things too far. In many ways this makes the characters more morally grey than ‘evil’.

This leads us to ask the question: do ‘good’ and ‘evil’ characters exist in ‘King Lear’? I believe that the answer is different for different audiences. Contemporary audiences were much more likely to interpret black and white situations in which people were either ‘wrong’ or ‘right’, an attitude that may have come from their strong relationship with religion, however more modern audiences can read into the ‘evil’ characters motivations and also put less emphasis on things which the ‘good’ characters believe to be important such as familial relationships, loyalty and parentage. Characters such as Gloucester seem cruel and unkind when looked at with a more progressive attitude. Gloucester mistreats his son because he is a bastard despite the fact that he is in part responsible for his illegitimacy, yet aligns himself with the good characters. Lear’s rashness and extreme reactions make him unlikable to modern audiences yet he is the main protagonist. It is debated as to whether this was Shakespeare’s intention, and I believe that he did set out to create complex, morally grey characters and the key to this is his treatment of Edmund. Edmund is fixated on his bastardy, every soliloquy he gives explaining his motivations revolves around his parentage, showing that his treatment has left him with deep psychological scars, a comment by Shakespeare on the contemporary society’s treatment of illegitimate children. This is linked to a special type of play, popular at the time of ‘King Lear’, morality plays showed audiences that whilst “sin is inevitable, repentance is always possible” There are many instances in ‘King Lear’ in which the characters do ‘evil’ or ‘good’ things, meaning that the dichotomy of black and white characters is one that does not exist in King Lear.

To conclude, I agree that Act 2 is about a struggle between the two opposing groups of characters but find it hard to label either group ‘good’ or ‘evil’ as Shakespeare has created layered, complicated characters who have believable motivations despite the actions they take.

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Censorship, Not the Painting, Must Go: On Dana Schutz’s Image of Emmett Till

Dana Schutz, “Open Casket” (2016), in the 2017 Whitney Biennial (photo by Benjamin Sutton/Hyperallergic)

The presence of blackness in a Whitney Biennial invariably stirs controversy — it’s deemed to be unfit or not enough, or too much. The current Whitney Biennial is no exception — the art press has been awash this past week with reports of a protest staged in front of a painting of a disfigured Emmett Till lying in his casket and a letter penned by an artist who called for the work to be removed and destroyed. The painter is Dana Schutz, a white American. The author of the letter is Hannah Black, a black-identified biracial artist who hails from England and resides in Berlin. The protestors are a youthful coalition of artists and scholars of color. The curators being called on the carpet are both Asian American. Debates about the painting and the letter rage on social media, to the exclusion of discussion of the many works by black artists in the show, most notably Henry Taylor’s rendering of Philando Castile dying in his car after being shot by police. This multicultural melodrama took a rather perverse turn on March 23, when an unknown party hacked Schutz’s email address and committed identity theft by submitting an apologia under her name to the Huffington Post and a number of other publications; it was printed and then retracted. Up to now, none of Schutz’s detractors have addressed whether they think it’s fine to punish the artist by putting words in her mouth.

Henry Taylor, “THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!” (2017) in the 2017 Whitney Biennial (photo by Benjamin Sutton/Hyperallergic)

I would never stand in the way of protest, particularly an informed one aimed at raising awareness of the politics of racial representation, a subject that I’ve tackled in various capacities for more than 30 years. A group of artists staging enraged spectatorship before an artwork in a museum strikes me as an entirely valid symbolic gesture. A reasoned conversation about how artists and curators of all backgrounds represent collective traumas and racial injustice would, in an ideal world, be a regular occurrence in art museums and schools. As an artist, curator, and teacher, I welcome strong reactions to artworks and have learned to expect them when challenging issues, forms, and substance are put before viewers. On many occasions I have had to contend with self-righteous people — of all of ethnic backgrounds — who have declared with conviction that this or that can’t be art or shouldn’t be seen. There is a deeply puritanical and anti-intellectual strain in American culture that expresses itself by putting moral judgment before aesthetic understanding. To take note of that is not equitable with defending whiteness, as critic Aruna D’Souza has suggested — it’s a defense of civil liberties and an appeal for civility.

I find it alarming and entirely wrongheaded to call for the censorship and destruction of an artwork, no matter what its content is or who made it. As artists and as human beings, we may encounter works we do not like and find offensive. We may understand artworks to be indicators of racial, gender, and class privilege — I do, often. But presuming that calls for censorship and destruction constitute a legitimate response to perceived injustice leads us down a very dark path. Hannah Black and company are placing themselves on the wrong side of history, together with Phalangists who burned books, authoritarian regimes that censor culture and imprison artists, and religious fundamentalists who ban artworks in the name of their god. I don’t buy the argument offered by a pair of writers in the New Republic that the call to destroy Schutz’s painting is really “a call for silence inside a church”; the vituperative tone of the letter hardly suggests a spiritual dimension — not to mention that the biblical allusion to silence in the church seems to come from a Corinthians passage about requiring women’s submission and obedience! I suspect that many of those endorsing the call have either forgotten or are unfamiliar with the ways Republicans, Christian Evangelicals, and black conservatives exploit the argument that audience offense justifies censorship in order to terminate public funding for art altogether and to perpetuate heterosexist values in black communities.

At the Whitney, a protest against Dana Schutz' painting of Emmett Till: "She has nothing to say to the Black community about Black trauma." http://pic.twitter.com/C6x1JcbwRa

— Scott W. H. Young (@hei_scott) March 17, 2017

Black and her supporters argue that the painting is evidence of white insensitivity; that a “painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist” cannot “correctly” represent white shame; that it’s an example of an unacceptable practice of white artists transmuting black suffering into profit; that white artists who want to be good should not treat black pain as material because it is not their “subject matter”; and that Emmett Till’s mother made her son’s dead body “available to Black people as an inspiration and warning” (my emphasis). The mainstream media’s “willingness” to circulate images of black people in distress is equated with public lynching. Despite attempts by her supporters to suggest that Black doesn’t really want to destroy the artwork, she recommends this explicitly in her opening line. The insistence that white people cannot understand black pain and only seek to profit from the spectacle of black suffering is reiterated throughout.

It is difficult to reason with the enraged, but I think it necessary to analyze these arguments, rather than giving them credence by recirculating them, as the press does; smugly deflecting them, as museum personnel is trained to do; or remaining silent about them, as many black arts professionals continue to do in order to avoid ruffling feathers or sullying themselves with cultural nationalist politics. (As a commercially successful young black artist once confessed to me over dinner, “My dealer says collectors don’t want to hear about my problems.”) Hannah Black’s letter can and should be unpacked separately from an interpretation of Schutz’s painting as a painting, or as the expression of a white person’s sentiment.

Black makes claims that are not based in fact; she relies on problematic notions of cultural property and imputes malicious intent in a totalizing manner to cultural producers and consumers on the basis of race. She presumes an ability to speak for all black people that smacks of a cultural nationalism that has rarely served black women, and that once upon a time was levied to keep black British artists out of conversations about black culture in America. Her argument is laced with an economically reductionist view of artistic practice and completely avoids consideration of the visual strategies employed by Schutz. Some of her supporters assert (without explanation) that abstraction in and of itself is illegitimate for representing a traumatic figure, a claim that ignores key 20th-century aesthetic debates about the problems with realistic depictions of extreme violence.

Kara Walker, “A Subtlety” at Domino Sugar Factory (photo by Hrag Vartanian/Hyperallergic)

Furthermore, in her letter, Black does not consider the history of anti-racist art by white artists. She does not recognize that the trope of the suffering body that originated in Western art with the figure of the Christian martyr informs much representation of racialized oppression — by white and black artists. She does not account for the fact that black artists have also accrued social capital and commercial gain from their treatment of black suffering. Numerous black artists have depicted enslaved bodies, lynched bodies, maimed bodies, and imprisoned bodies in the early stages of their careers — and then moved away from such politically charged subject matter without having their morality or sense of responsibility impugned. Others, like Kara Walker, who delve into complicated racial fantasies that are tinged with abjection or eroticism, have been on the receiving end of character assassinations by black people who find the work disrespectful or prurient and claim to speak for “the community.” Whether Black intends it or not, her dismissive treatment of Schutz’s painting, her essentialist position on black and white racial identities, and her use of offense as a rationalization for censorship reinforce elitist and formalist views that ethical considerations don’t belong in the aesthetic interpretation of art.

The authority to speak for or about black culture is not guaranteed by skin color or lineage, and it can be undermined by untruths. My 25 years of teaching art have shown me that a combination of ignorance about history and the supremacy of formalism in art education — more than overt racism — underlie the failure of most artists of any ethnicity to address racial issues effectively. Many young black artists harbor deep insecurities about their capacity to “represent the race” because their Eurocentric art education leaves them with few tools or references to work with. Only a privileged few hail from socially engaged families committed to exposing their children to black art, history, and cultural traditions. They also face intense social pressure from teachers, peers, and art world power brokers not to “rock the boat” with political discussions about race. I myself was once grilled at a job interview by the white male search committee chair about whether I agreed with black artists’ criticisms of Kara Walker — which I understood immediately to be the litmus test of my acceptability at an elite institution.

As a teacher I’ve been privy to dozens of confessions from students of color at elite art schools who have been scrutinized and intimidated by visiting artists, professors, and peers if they’re perceived as obsessed with race or overly concerned with politics. I’ve been screamed at by frantic students who are afraid of calling themselves “black artists” because arts professionals have warned them not to do so. While elite art schools deploy tokenist inclusion strategies to create the impression of diversity, they actively avoid revising curricula and discourses of critique; the end result is that they produce artists and curators who lack formal opportunities to engage with critical race discourses and histories of anti-racist cultural production. In the absence of informed discussion, we get unadulterated rage.

The July 23, 1964 edition of Jet magazing, which featured the photographs of the murder of Emmett Till. (via Pinterest/jetcityorange.com)

Hannah Black claims to know more about black suffering than Schutz, but her treatment of history could use more accuracy and depth. She claims that Mamie Till wanted her son’s body to be visible to black people as an inspiration and a warning; however, according to Emmitt Till’s cousin Simeon Wright, who was with him the night of his capture and attended his funeral, Mamie Till said “she wanted the world to see what those men had done to her son” (my emphasis). There was no exclusion of non-black people implied, nor was it a deviation from the custom of having an open casket. That casket was donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture by Till’s family to be on view for all, not just black, people. Scholar Christina Sharpe’s assertion in an interview with Hyperallergic that if no white people attended the funeral, no whites were supposed to see the casket doesn’t hold. The trial of Till’s murderers was filmed and shown widely, as were photographs of his funeral. Those photographs galvanized the Civil Rights Movement: activist leaders strategically and adeptly circulated them to encourage blacks and whites in the North to join the struggle, and in order to shame politicians by casting doubts on America’s adherence to its democratic ideals.

My mother, a Cuban immigrant, arrived in New York shortly before Emmett Till was murdered in 1955. She was not physically present at his funeral, but saw pictures of him in the casket and learned about his death from the news. She was so appalled by the violence that she never got over it. She talked to me about the Till case throughout my childhood and refused to let me or my brothers visit the Deep South. She was a pathologist who performed hundreds of autopsies, but the image of a disfigured Emmett Till in the casket left an indelible mark on her memory as the archetypal representation of American racism.

Black claims that Schutz’s painting is yet one more example of white representation of black suffering as an exercise in commercial exploitation. She also suggests that such representations cater to a morbid fascination with black death that she associates with lynching as a public spectacle. It is undeniable that reality TV shows lionizing cops in pursuit of an endless stream of black and brown men are extremely lucrative for their white producers. It’s also true that there are plenty of examples of simplistic and fetishistic representations of black bodies in Western art and advertising. However, it is reductive and inaccurate to claim that all treatment of black suffering by white cultural producers is driven by commercial interests and sadistic voyeurism. Black overlooks an important history of white people making anti-racist art, often commissioned by Civil Rights activists.

That history extends back to 19th-century abolitionists who used photographs of the branded hands and scourged backs of slaves to denounce the inhumanity of slavery and to target white audiences in the North. It includes the works made by white artists Paul Cadmus and John Steuart Curry, who drew and painted blacks struggling against white mobs for the 1935 exhibition An Art Commentary on Lynching, organized at the behest of the NAACP in support of its anti-lynching campaign. It also includes Charles Moore’s and Danny Lyon’s celebrated documentary photographs of police brutality toward black Civil Rights activists that circulated among white people at home and abroad, and helped push a reluctant US Congress to pass Civil Rights legislation. It encompasses the Minimalist sound piece “Come Out,” composed by avant-garde musician Steve Reich in 1966 for a benefit for the Harlem Six upon the request of a Civil Rights activist. Reich’s piece consists of a looped sound recording of Daniel Hamm, a young black man in Harlem who was a victim of false arrest and police violence. The speech fragment repeats his explanation of how he turned his physical suffering into spectacle, making one of his bruises bleed visibly so that the police would finally take him to a hospital.

In citing these examples, I do not mean to suggest that all artistic representations of black oppression by white artists and all curatorial efforts to address race are well intentioned, or that they are all good. However, the argument that any attempt by a white cultural producer to engage with racism via the expression of black pain is inherently unacceptable forecloses the effort to achieve interracial cooperation, mutual understanding or universal anti-racist consciousness. There are better ways to arrive at cultural equity than policing art production and resorting to moralistic pieties in order to intimidate individuals into silence. Indeed, the decolonization of art institutions that Black’s supporters claim to want entails critical analysis of systemic racism coupled with a rigorous treatment of art history and visual culture. Arguing that Schutz’s painting must be destroyed because whites aren’t allowed to depict black suffering, blaming Schutz for capitalizing on the entire history of racist violence in America, suggesting, as some have done on social media, that she’s tainted by having collectors who are heartless real estate developers, while ignoring the work by a dozen or so black artists in the biennial is not going to advance anything.

Over the past 40 years, critics, cultural historians, and artists themselves have devoted a good deal of attention to the problems they see with such exhibitions as Harlem on My Mind, The N*gger Drawings, and “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art and such white artists as Rob Pruitt and Kelley Walker, whose treatments of black subjects have been deemed exploitative. Black British artist Isaac Julien and art historian Kobena Mercer first gained international attention in the 1980s for their critical analysis of white artist Robert Mapplethorpe’s depictions of black men, launching an extensive debate that eventually resulted in Mercer altering his original stance to acknowledge more complexity and complicity in interracial relations within gay subcultures. My point here is that reasoned assessment involves more nuanced evaluative criteria, ones that do not essentialize racial identity, impute intent, or ignore the way distinct cultural forms hold differing degrees of power when it comes to racial relations.

The impact of an individual artist’s single, non-mass-produced artwork is qualitatively and quantitatively different from the coercive power of an advertising campaign or a Hollywood blockbuster, and to discuss their effects as if they were the same is hyperbolic and unjust. True, Dana Schutz did not create her painting at the request of Civil Rights activists — however, the fact that she was stirred to resurrect the image of Emmett Till’s open casket is a sign of the success of the Black Lives Matter movement in forging awareness of patterns of state violence by politicizing the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, and others. The specter of Till’s death at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan lingers behind these more recent deaths at the hands of the police. Though six decades apart, the circulation of images from these tragedies serves the same function — and sadly signals how little American society and race relations have changed. That is not what mainstream public education teaches American children, and it is not what white liberals would have Americans believe. Schutz is stepping out of line with the dominant culture in underscoring the connection.

Schutz has stated clearly that she never intends to sell the painting, so there is little evidence that she’s seeking to enrich herself by it. Artists, myself included, often explore what troubles them for reasons other than personal gain — and if I want an art world that can handle more than pretty pictures and simplistic evocations of identity, I understand that I will have to support not only difficult subjects but clumsiness and mistakes. Though Schutz is not known for painting works about social issues, her inclination to respond to a heightened awareness of violence and injustice is hardly unusual and not inherently opportunistic; other white artists have changed their approach and focus in times of intense social unrest.

The Art Workers’ Coalition “And babies” (1969) has been described as “easily the most successful poster” opposing the Vietnam War. (photo via Wikipedia)

Philip Guston, “Untitled (Poor Richard)” (1971) (photo by Benjamin Sutton/Hyperallergic)

Philip Guston, for example, dropped abstraction in the 1960s and began making eccentric renderings of Klansmen and cartoons lampooning Richard Nixon. The Art Workers’ Coalition created the iconic, antiwar “And Babies” poster by reframing a news photo of the Mai Lai Massacre featuring dead Vietnamese people killed by US soldiers in 1969. Robert Gober, not known for an ongoing commitment to racial issues, produced what he saw as a commentary on white guilt by juxtaposing a white sleeping man with a black hanged man in a 1989 lithograph — and generated a similar controversy to today’s when black employees at the Hirshhorn Museum, where it was exhibited, protested. Hannah Black demands that all whites wallow in shame about racist violence against blacks, but in the case of Gober’s work, his attempt to represent white guilt did not prevent a protest. And despite that protest, Gober sold his piece to Harvard University, whereas Schutz has pledged not to sell hers at all.

The most perplexing criticism that’s been bandied about regarding Schutz’s painting, both on social media and in discussions I’ve had, is that some great harm has been inflicted by the act of abstraction, as if the only “responsible” treatment of racial trauma is mimetic realism. Strangely, though Henry Taylor’s painting of Philando Castile is no more realist in its rendering than Schutz’s, he’s been left alone by protesters. I would have liked to think that the days of Black Arts Movement militancy were long gone, but it seems that for some, they are not. There was a time when political correctness in black art was linked with realist aesthetics and didacticism, but it’s been widely since recognized that this stance led to the marginalization of black abstractionists. Masters such as Romare Bearden, Bob Thompson, and Alma Thomas, and even contemporary abstractionists like Jennie Jones, have bristled at the notion that authentic blackness must be equated with realism and that black art must be subject to sociological approval before being evaluated aesthetically.

Alma Thomas, “Apollo 12 ‘Splash Down’” (1970), acrylic and graphite on canvas, 50 1/4 x 50 1/4 inches (courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY)

There’s a fundamental misunderstanding at work in damning abstraction by associating it with erasure and irresponsibility. Abstraction, like mimeticism, is an aesthetic language that can be interpreted and used politically in a range of ways. It doesn’t necessarily mean erasure, but it does complicate the connection between perception and intellection — something that deeply thoughtful painters like Gerhard Richter have taken advantage of in order to make us reflect on how photographic images represent history and structure memory. Jacob Lawrence “abstracted” his black figures, not to obscure their humanity but to explore new ways of evoking ethnic identity and communal purpose through color and dynamism. The story of how the CIA championed Abstract Expressionism at the height of the Cold War to counter Socialist Realist propaganda is well known; however, abstraction can also be mandated by religious beliefs or, in the repressive contexts of many authoritarian states, serve as a rejection of narrow-minded populism. Perhaps the best argument in favor of abstraction was articulated by Theodor Adorno after the Holocaust, when he asserted that realist representations of atrocity offer simple voyeuristic pleasure over a more profound grasp of the horrors of history.

Whether or not we like the painting or consider it her greatest work — I do not, but think it still has value — Schutz’s decision to refract an iconic photograph through the language of abstraction has forced the art world out of its usual complacency and complicated the biennial’s uniformly celebratory reviews. She has, perhaps inadvertently, blown the lid off of a biennial that features an almost too perfect blend of messy painting, which appeals to conservatives, and socially engaged art, which appeals to the more politically minded. As far as I’m concerned, that’s not such a bad thing, given the ghastly state of American political culture at this moment.

The 2017 Whitney Biennial continues at the Whitney Museum (99 Gansevoort Street, Meatpacking District, Manhattan) through June 11.

The post Censorship, Not the Painting, Must Go: On Dana Schutz’s Image of Emmett Till appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2nZKfxd via IFTTT

0 notes