#but I wanted to include the oldest (within the 2019-present frame) and the ones that are likely to get finished soon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

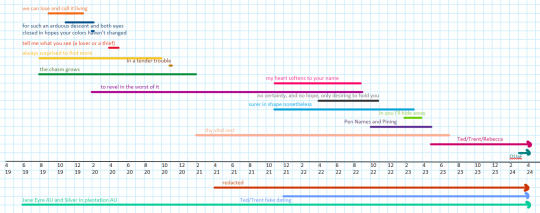

what did I do today? oh you know. went through and looked at how long my fics have taken to write. and then made a graph. obviously

#I looked at my published works from pre-2019 also but obviously decided not to include them in this#largely because I don't know for sure when I started them because I was doing some handwriting#also I didn't look at all my wips because there are a million of them#but I wanted to include the oldest (within the 2019-present frame) and the ones that are likely to get finished soon#god what a spectacular waste of time but I did find it interesting#writing tag#in case anyone is curious - the shortest time for any of these was in a tender trouble which I wrote in four days#followed by both eyes closed which took about 12#and obviously the longest would be the two black sails fics I started almost five years ago#there are some other things from other fandoms I started earlier but the likelihood of those ever getting finished is. low#average for my published works is roughly nine months. feels about right. closest thing to birthing a baby I'll ever do lmao

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Paris is Burning

The Article Paris is Burning is a critical article written by bell hooks to express her observation and opinion on the documentary Paris is Burning directed by Jennie Livingston. bell hooks is an African American female author, professor, feminist and social activist. hooks has constructed the article in order to explain how the gay black men experience is not fully represented in the documentary film.Livingston is a lesbian white women director, producer and activist; she uses film to capture vouge, drag in the gay community of New York City. I introduce both women in order to comprehend the lenses these women have and how they carry their message. In the class of Blacks and Media we have touched on the history of African Americans in social media, politics, gender and now sexual orientation. In this thought paper I will evaluate the documentary Paris is Burning by Jennie Livingston and bell hooks response in her article Paris is Burning. Gay Black men, transgender/transsexual or non-binaries are considered at threat to societies norm because the United States inevitably has history of being racists, patriarchal and sexist.

In the 1990 film Paris is burning Livingston documents the lives of black gay men, transgenders/transsexuals influence in the culture of drag and vogue. The film begins with a narrative from one of the men having a nostalgic moment and stating “you are black, you are male and you are gay, you are gonna have a hard time if you gonna do this you are gonna have to be stronger then you ever imagined” three qualities that are stigmatized in Americas misogynist racist society. Homophobia is based on the fear of homosexual behavior it was also included in the DSM (American Psychiatric Association) diagnoses book as a disease/ mental disorder. In the 1980’s there was a HIV epidemic and the scientific myth was that it was only transmitted through same sex engagement. This deadly virus brought fear to many people and it increased the fear and alienation of people (especially men) in the Queer community. The film introduces the ritual of preparing and attending at a ball, it all began in Vegas when men would cross dress like Vegas girls but as new generations joined the balls the culture shifts from preparing the extravagant gowns with beads and feathers to a more simple like a movie star or a model. Here we see a transition that cross dressing is not only for a night out at a gay gala it has also become a place for validation. Some men find it more comfortable embodied as women and desire to continue to present themselves as women. Livingston focuses on the art, community and ambitions black gay men have to be understood, famous and successful. She structured the film as the men having true feelings, thoughts, ideas and dreams; all of them being no less than any other person. The film emphasizes on the struggles gay and transgender/transsexual men endure in society. Not being accepted for being black male, not being able to get jobs because of their sexual orientation and race. The men have built communities that allows them to be comfortable in their own skin because they yarn to be accepted therefore, they create families and houses with mothers and children in order to be each other’s’ anchors.

In the previous article Oppositional Gaze, hooks emphasize on the psychological and sociological effects of white supremacy on framing, racism and feminism. In this article she takes a similar stance but instead she goes to argue that the gay black man’s struggle was not being represented to its full authenticity. Bell argues “these images of black men in drag were never subversive, they helped sustain sexism and racism” (146) the bigotry in America now feels justified for dehumanizing black people because they appear uncivilized because of their scornful manners. She also states “I can see the black male in drag was also disempowering of black masculinity” (146) because femininity is perceived as a weakness because of gender and the men in drag aim to convey the attributes of a women they are frowned upon and have a low social status. I disagree with this statement because in the documentary the men are sustaining their self-esteem and thriving on the power of seduction. bell perceives power to be a patriarchal status, she lacks to understand that seduction is another form of power. The men use the power in their work of sex trafficking. The men in the use their bodies and exchange of sex in order to make a living and also to validate their sexuality and seduction. Being that man transgender/ transsexual men were able to make a living out of this profession demonstrates the taboo is fetishized but not welcomed. Although The opportunities for jobs as a gay black or transgender/transsexual man in society is difficult to attain and maintain because of the taboos attached to stigmas.

Different societies in different communities determine what is wealth, success and power based on the structure of social stratification. The drag and transgender/transsexual ideal of beauty, success and riches is to embody a white woman. The goal is to be accepted, valuable and ‘normal’ because “the brutal imperial ruling-class capitalist patriarchal whiteness that presents itself – its way of life – as the only meaningful life there is” features of European decent has subconsciously been ingrained in the minds of African American cognitive to believe that to be successful, beautiful and rich is to imitate the authorities grouping. In the film Livingston interviews Dorian Corey, one of the oldest legends of drag in Harlem. Dorian shares the ideals of beauty is to express white feminine attributes ‘if you capture the great white way of living or looking or dressing or speaking you are a marvel” this is an example to show the struggle that gay black men in drag have is to completely modify their race and gender in order to be a sensation. Hook argues “the idea of womeness and femininity is totally personified by whiteness. What viewers witness in not black men longing to impersonate or even to become ‘real’ black women but their obsession with idealized fetishized vision of feminity that is white” (148). In the ball the category ‘Realness’ is structured to appeal to the audience as to have feminine features because the more feminine you appear because it is not only cross dressing it is a contest to be able to manipulate society as a transgender/transsexual then you gain a price. Octivia was a transgender in the film whom was hoping to change her sex ‘this is not a game for me or fun, this is how I want to live my life” there are not enough black models for her to aspire to appear like so in her room there are posters of white women. Americas ideal beautiful women is a thin figured white rich woman, it has been ingrained in the minds of Americans across the board despite the sex, gender, sexual orientation or social status. Media has a large influence on this portrait because of the people marketing and financing the industries is dominated by white men.

I enjoyed the film and the article because it highlights the struggles, hopes and dreams of being a gay or transgender/transsexual in the black subculture. The documentary Paris is Burning demonstrates the sub gay black community in a humaine vulnerable form. Although bell argues Livingston should have emphasized more on the struggle of being a gay black man, I believe Livingston challenged societal norms by illustrating the stories and experience gay black men are challenged within society and their own community. This film is inspirational to others with similar paths. In the 80’s because of the HIV epidemic Homophobia really affected the gay community because it was known as the “gay man’s plaque” justifying religions argument against same sex relationships and leaving the queer community to question “why is loving love a sin?”. Livingston did a phenomenal job casting transparent people in their journey, I also read that she did activist and participated in the HIV community in NYC. I also want to share that after watching the documentary I was able to visually comprehend the influence black, queer, fashion, psychological evaluation and comprehension along with art culture has influenced todays dance, media, fashion, makeup, queer activism, medicine ext. I watched Rihanna’s 2019 fashion show on amazon prime and I was able to see the transition and progress that the black queer community has influenced in today’s culture across the board.

3 notes

·

View notes