#buck’s lore in this is him just getting out of PA and trying to find his footing somewhere

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

alternate meeting AU where Tommy’s a motorcycle guy. he’s got a 1998 harley-davidson road king that he’s put a lot of money, cursing & sweat into and it runs as smooth as butter.

Tommy who decides to pack up his life for a couple of months and travel cross country on his bike. he sees the sights, stays in some shitty motels and meets all kinds of people all along the way from california to maine.

Tommy who stops in loveland, ohio for a quick break on his way back to california and stumbles into a diner off the nearest exit for something to eat and meets the prettiest guy he’s ever laid eyes on who’s asking him “what can i get for you, sir?”

and Tommy’s out of it, not only from driving for the past 15 or so hours on a couple hours of sleep, but because he’s hungry and this guy is too gorgeous and Tommy’s sure he has the absolute worst case of helmet hair right now. just his luck.

Evan. his name tag said ‘Evan’.

“sir?”

and Tommy’s snapping back to reality, brushing his fingers through his hair.

“sorry, i’m just a little out of it.”

a small laugh. sweet and light. Tommy thinks he might just throw up butterflies.

“i saw you pull in on your bike. long drive?”

“you could say that.”

that smile. Evan’s smile. it was like feeling the warmth of the sunlight across your skin on a cold day.

“coffee. you need coffee. there’s a fresh pot brewing right now.”

“i’d love that.”

“great. maybe you can decide on what you want to eat while i’m gone?”

“sure.”

“okay.”

Evan stood there for a second, holding Tommy’s gaze before clicking his pen and turning on his heel, walking towards the kitchen.

it’s then that Tommy decides maybe he could stay awhile. he’s sure he remembered seeing a sign for a hotel just along the exit ramp. and besides, maybe there was something worth staying for in loveland, ohio.

.

#bucktommy#just been thinking about this a lot#lapslock is on purpose#buck’s lore in this is him just getting out of PA and trying to find his footing somewhere#ficlet#?? sort of

139 notes

·

View notes

Photo

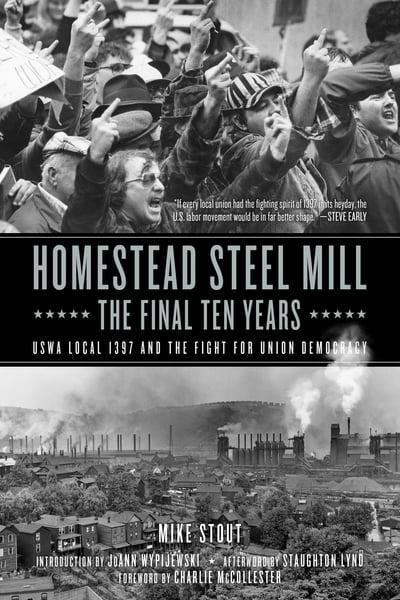

Book Review: Mike Stout’s ‘Homestead Steel Mill’ Is a Manual for Organizers

Homestead Steel Mill: The Final Ten Years

USWA Local 1397 and the Fight for Union Democracy

By Mike Stout

PM Press 2020

By Carl Davidson

Keep on Keepin’ On

Mike Stout’s remarkable new book of a recent large-scale class battle in Western PA can be read in many ways. First, it’s a history of Homestead steelworkers in the last years of their battles to improve their conditions and save their jobs. It’s also Stout’s personal autobiography of a working-class youth radicalized by the 1960s and 1970s and the culture of rebellion of which he was a part. Then one can read it as a fine example of sociological investigation and economic analysis of the Pittsburgh region.

All those brief summations are fine. But most of all, within all these, Stout has written an organizing manual for radicalizing workers of any age embedded in large manufacturing industries. Despite relative declines, these still exist in the Rust Belt and elsewhere. Unfortunately, the current younger workers in them have never been in a union and only know about them from the lore passed down by fathers and grandfathers. Thus nearly all of them are in dire need of new crews of organizers like Mike Stout--or who at least have studied this book.

What makes Stout’s narrative unique is the quality of his personal commitment. In the 1970s, thousands of radicalized young college students, with or without degrees, went into the factories to organize ‘for the revolution.’ A few did well; most did not. But Stout was not one of these. Getting into the mill and the struggle there was a step up for him, as an unemployed kid from Kentucky trying to make a living as a political rock and roller and folk singer. He desperately needed a day job, and getting into Homestead mill enabled him to do both, however hard the work. He had more in common with the returning Vietnam vets in the mill than transplanted student radicals, not that he lacked respect for the latter.

This is not to say that the thousands of workers in a four-mile-long mill were monolithic. Far from it. Stout goes on at length throughout the book describing rivalries between a dozen nationalities, between races and sexes, generations, skilled and lesser skilled, and old timers and newcomers.

‘As the book’s title suggests, however, Stout sticks to his outline of ‘the last ten years,’ although it stretches a bit longer to include the aftermath. At the start, hardly anyone had a premonition of what was in store for them—the mills had been there as long as anyone could remember, and thus they would continue into the future. What was different was the owners were squeezing the workers harder, and after the Red purges of the 1950s, the unions had grown cozier with the bosses, The stage was set for rank and file insurgency, and this is the setting Stout entered as a new hire.

Nearly everyone in Western PA gets a nickname in high school or at work. Stout was no different, and his fellow workers tagged him ‘Kentucky’ and it stuck. He laid low in his early months, trying to find the best ways to survive and thrive working rotating shifts. The older ‘beer and a shot’ workers in the bars raised an eyebrow because he only drank red wine, but he slid in easy with the younger crowd that liked their alcohol combined with reefer. Mainly Stout had his eye on a crane operating job, but he was amazed at the skills—and luck—involved to do it safely. It would take some time. But early on, he got the reputation as a guy who resisted any crap thrown at him by foremen. This led him to find a small group of militant workers seeking to find a way to change the union into an instrument that would fight for them.

They certainly had a history behind them. Homestead was a center for more than 150,000 steelworkers in Western PA and neighboring states. The ‘Battle of Homestead’ of the previous century had been compared to the Paris Commune, and fierce battles of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in the 1930s had helped found the CIO. FDR’s Labor Secretary, Frances Perkins, visited the Homestead Works, but forbidden to speak on the grounds. Legend has it that she spotted a US flag flying over a post office, made her way there, where she delivered a fiery speech for the rights of labor.

Stout quickly joined up with the rank-and-file group and started planning a campaign. Perhaps their most important early project was to start a plant-wide newspaper, the 1397 Rank and Filer. Stout’s description of its impact and evolution over the years is an instructive tale of how a newspaper can become a ‘collective organizer.’ When an organization had to spread the word over a mill measured in square miles, and where thousands of workers on one end often knew little of events on another, it was indispensable. Moreover, the mill was subdivided into what Spout called ‘feudal fiefdoms’ ruled by petty tyrants with divide and rule tactics

The workers also had to have access to the newspaper and to trust it. So it was open to letters, hand-drawn cartoons, and a popular feature called ‘Plant Plague’ that expose the injustices and pure nastiness of plant foremen. It also published studies of the union contract and the misdeeds of the union officials, all with an eye toward replacing them.

After many skirmishes, it paid off. The Local 1397 Rank and File Caucus eventually evolved from a militant minority to a progressive majority of union members and took over the local. There’s a long story in between, of course, but it’s worth reading Stout’s account in full.

For his own role, Stout appears to have made several wise decisions early on and stuck to them. One was to keep his connection with the editorial group that put out the newspaper, both before and after the takeover of the local. The other was to avoid seeking a top post for himself. Early on, because of his unflinching willingness to not only defend workers with a beef, but also to get them involved in their own defense, he rose to a more organic leader. This meant he became a ‘griever’ or grievanceman, eventually becoming a chief griever, and one of the best of them. It might take years, but Stout often won his cases. Even if a worker died, he persisted, winning benefits for surviving families.

Another reason for Stout’s influence was practicing a consistent left politics, expressed in his own terms, and never trying to hide his values, despite red-baiting and other attempts at personal slanders. He offers several accounts of standing up against racism and sexism when it erupted among the workers themselves, as well as used as a weapon by supervisors and other higher-ups.

Stout was known as a socialist inside and outside the mill. At one point, he was connected with the Revolutionary Union, an early 1970s Marxist-Leninist nationwide group. It had rank-and-file union newspapers in other cities and industries, but Stout detached from it as it became too sectarian for his taste.

But what is powerfully portrayed in the book is Stout’s astute combinations of politics with culture. Its pages are replete with the lyrics of dozens of songs written for working-class battles in Homestead and beyond. Together with them are stories of how music was used for firing up picket lines or finding creative ways to raise money. It helped that Stout was good at it, not just knowing a few old labor songs, but pulling together full-fledged rock band performances.

By the middle of the book, you get pulled into the sense of impending doom shared among the workers. What we now know as ‘the Rust Belt’ was being born. Faced with competition abroad and poor management at home, neoliberal capitalism tore up its postwar ‘social contracts.’ Corporate boardrooms closed plants here and shipped production offshore in search of cheaper labor. In some cases, it used modernization to cut workforces by half or more, while keeping production at old levels.

At this point, both Local 1397 and the USW generally learned that unions could not survive without wider allies. Stout unfolds the saga of the nationwide movements in the 1980s and 1990s against plant closings. Workers sought community and government partners in an effort to save profitable businesses by innovation and reorganization, or even in some cases, attempting to buy out and take over the plants themselves.

None of these paid off much, at least in the Homestead area. Stout describes somes of the proposed deals as ‘Last Suppers before our execution.’ But he nonetheless tells a tale of the value of persistence, where he continued to carry on battles and win major grievances for workers even after the plant was closed, the union reduced to a shell and Stout himself among the unemployed. He soldiered on by forming a union print shop as a workers coop, as well as making a few bucks playing concerts here and abroad.

Despite this grim conclusion, ‘Homestead Steel Mill: The Last Ten Years’ is a hopeful book. It draws positive lessons from defeats, showing the need for wider and more protracted political strategies. It’s not enough to press liberals to do good things; workers need a vision of taking power themselves. And the lessons of its victories stand out as well. Workers can win when they are well-organized, well-informed, and well-inspired. They need a culture of solidarity and mutual aid to fight for what belongs to them, not only the part, but the whole deal. You can buy the book HERE

1 note

·

View note