#bro you are in an existential war with an enemy far more powerful than you

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The fact that a Ukrainian twitter mutual of mine, who lives in a front (!!!) Donbass city, an area often targeted and that was partially and temporarily occupied by Russia back in 2014 (fully under Ukraine's control today though thank goodness), messages me every time she has wi-fi to make sure I'm ok is just. wild.

#not things i expected to see in this timeline#esp. since like. it has always been the other way around#and yeah with a bit of rockets and a bit of terror here every now and then#but not to the extent it's been now ofc#it's also touching but like#bro you are in an existential war with an enemy far more powerful than you#here our biggest existential threat is our evil dysfunctional government#and yes a genocidal terror oragnisation that wants us all dead but like they do not have the means to for now#they will kill as many of us as they can - which we have already seen - but they simply don't have the means to wipe us all out for now#like i'm touched but im also like bro please worry about yourself first <3

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Custom Toonami Block Week 66 Rundown

Code Geass: Lelouch has to stop the execution of all his side characters while dealing with his Fake Za Warudo little brother. Eventually he hacks his way into Rolo’s tragic backstory and plans out a cheesy sitcom character arc for him where found family wins out even though they’re enemies which someone as lovestarved as Rolo can’t help but eat up. It’s almost like sending someone who does exclusively assassinations and has never been in social situations long enough to form a personality and stops time to murder people at the drop of a hat to do a deep cover year long infiltration mission where he has to get emotionally close to the target was a terrible idea. Anyway Lelouch has Rolo on his side now and I’m sure that won’t backfire in any way.

Inuyasha: Muso continues to try and capture Kagome before getting Wind Scar’d into an existential crisis and going back to Onigumo’s cave to remember his shit. Kaede immediately puts together who Muso is and leads Kagome there but Inuyasha and co. are too stupid to figure it out so Naraku straight up takes Kagura out of gay baby jail for betraying him to send her to go tell them the answer. Naraku goes to brag about being able to go kill Kikyo like Voldermort touching Harry in Goblet of Fire but it backfires since apparently simping for Kikyo is engraved in his soul and he still can’t hurt her which makes his attempt at bragging really awkward and he has to go get Muso back. Meanwhile Muso’s turned into a demon scorpion, and stabs Inuyasha through the gut, as you do.

Yu Yu Hakusho: Kuwabara starts up his fight with Byakko, the beast that chases Botan and Keiko in the opening even though they’re barely in this arc. Weirdly enough he shows off his new powers BEFORE the fight so there’s no suspense to getting his new move when he finally pulls it out. Not sure if this is cool or not, on the one hand it means that Kuwabara has to do more than just show a new technique to be cool enough to finish on, on the other hand the fight is still basically using that technique and slightly altering it, and knowing that his sword can get long now takes some of the punch out of it, kinda mixed on this one.

Fate Zero: Okay so this first episode is long so I’mma try to cliffnotes this shit. Basically the Grail War starts up ad we have our combatants, a high schooler because every anime needs one of those, male Homura Akemi, Priest Alucard who’s acting more like Father Anderson in this role, Rin’s dad Miles Edgeworth, the current host of the Aburame Clan’s secret bug jutsu who’s just trying to save a child and must be punished for it, and that one racist teacher you had in high school that everyone has to pretend to respect. Last person’s still unaccounted for but this seems fun so far, the fucking lore is still dense as stone but the premise is ‘bunch of assholes want fight for big wish’ so I can get around that part.

Konosuba: Kazuma is run over by a car and… BECOMES A SPIRIT DECTIVE, FIGHTING GHOSTS AND DEMONS WITH HIS FINGERTIP LASERS! Wait, wrong anime, still kinda makes me laugh though out of all the weird isekai premises that kill off the main character, Konosuba ups the anty on the whole “Oh no, the person you saved would’ve been better off if you left them alone” thing from Yu Yu Hakusho. Anyway I’m pretty sure you guys all know the story of Konosuba by now, useless goddesses, RPG worlds, isekai shenanigans. I kind of really like how even though it’s cynical and sarcastic, it’s not a dour hopeless affair, there’s this odd upbeat charm that even though nothing’s going our heroes’ way that they’ll still be okay and find happiness where they can. This very easily could’ve become an Everybody Hates Chris thing where the world’s just shitting on them all the time and the story becomes predictable because you know nothing will every work out for them but this does a good job of making them underdogs while still throwing them bones every now and them, underbones for underdogs.

Sailor Moon Crystal: Usagi is an average kid, that no one understands… actually she’s quite a bit below average, she kinda gives Aqua a run for her money in uselessness, she’s essentially High School Dropout Barbie in this episode which is weird but I also know it’s to give her room to grow and also that she’s not meant to carry the whole show by herself. It’s just kinda amusing how the whole episode paints Usagi as not particularly good at anything or even all that nice, even after she gets her powers they essentially run on autopilot and beat the monster for her. Still it is a good spot that she wants to help her friend and I like how they keep Tuxedo Mask’s involvement to a minimum, like he doesn’t actually do anything (memes) and is just like “you got this” which is not necessarily the reaction you’d have to someone who literally beat a crowd into submission by crying at them but it’s nice to have him in an emotionally supportive role for this first outing. I’m not quite sure how this series will sit with me overall but I feel like I’ll get a better feel for it once we have the ensemble gathered and hit our stride here.

Durarara!!: The Human traffickers from Episode 1 screw up and take a totally legit Japanese man who’s definitely not an Italian illegal immigrant for Seiji’s sister’s fucked up pharmaceuticals experiments. Unfortunately said totally legit Japanese man is a tertiary friend of Dotachin’s group and they hunt their asses down. Celty’s also on the case but by the time she gets there they’ve already found them and given them manga-based torture sessions to find out their secrets so everything’s cool. Man these guys ride or die like nobody’s business, they freaking love this Italian dude for getting their friend tickets to an Idol show and giving language-based malapropisms, what bros they are.

Overall the three new shows worked out pretty well this week, Sailor Moon’s a bit of a rocky start but I knew that getting into it. I like the setup for Fate Zero a lot better than the start of Unlimited Blade Works so I’m excited for where that’ll go. And Konosuba did put a big dumb smile on my face with its hard luck lighthearted antics so I’m looking forward to the future of the block for the next few weeks.

#ooc#Toonami#Custom Toonami Block#Code Geass#Inuyasha#Yu Yu Hakusho#Fate Zero#Konosuba#Sailor Moon Crystal#Durarara!!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Crowd Doesn’t Just Roar, It Thinks: Warner Bros.’ All-Talking Revolution

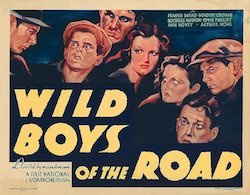

“Iconic” is a gassy word for a masterwork of unquestioned approval. But it also describes compositions that actually resemble icons in their form and function, “stiff” by inviolate standards embodied in, say, Howard Hawks characters moving fluidly in and out of the frame. Whenever I watch William A. Wellman’s 1933 talkie Wild Boys of the Road, these standards—themselves rigid and unhelpful to understanding—fall away. An entire canonical order based on naturalism withers.

To summon reality vivid enough for the 1930s—during which 250,000 minors left home in hopeless pursuit of the job that wasn’t—Wellman inserts whispering quietude between explosions, cesuras that seem to last aeons. The film’s gestating silences dominate the rather intrusive New Deal evangelism imposed by executive order from the studio. Amid Warner Bros.’ ballyhooing of a freshly-minted American president, they were unconsciously embracing the wrecking-ball approach to a failed capitalist system. That is, when talkies dream, FDR don’t rate. However, Marxist revolution finds its American icon in Wild Boys’ sixteen-year-old actor Frankie Darro, whose cap becomes a rude little halo, a diminutive lad goaded into class war by a chance encounter with a homeless man.

“You got an army, ain’t ya?” In the split second before Darro’s “Tommy” realizes the import of these words, the Great Depression flashes before his eyes, and ours. No conspicuous montage—just a fixed image of pain. Until suddenly a collective lurch transmutes job-seeking kids into a polity that knows the enemy’s various guises: railroad detectives, police, galled citizens nosing out scapegoats. Wellman’s crowd scenes are, in effect, tableaux congealing into lucent versions of the real thing. The miracle he performs is a painterly one: he abstracts and pares down in order to create realism.

Wellman has a way of organizing people into palpable units, expressing one big emotional truth, then detonating all that potential energy. In his assured directorial hands, Wild Boys of the Road sustains powerful rhythmic flux. And yet, other abstractions, the kind life throws at us willy-nilly, only make sense if we trust our instinctive hunches (David Lynch says typically brilliant, and typically cryptic, things on this subject).

I’m thinking of iconography that invites associations beyond familiar theories, which, in one way or another, try to give movies syntax and rely too heavily on literary ideas like “authorship.” Nobody can corner the market on semantic icons and run up the price. My favorite hot second in Wild Boys of the Road is when young Sidney Miller spits “Chazzer!” (“Pig!”) at a cop. Even the industrial majesty of Warner Bros. will never monopolize chutzpah. The studio does, however, vaunt its own version of socialism, whether consciously or not, in concrete cinematic terms: here, the crowd becomes dramaturgy, a conscious and ethical mass pushing itself into the foreground of working-class poetics. The crowd doesn’t just roar, it thinks. Miller’s volcanic cri de coeur erupts from the collective understanding that capitalism’s gendarmes are out to get us.

Wellman’s Heroes for Sale, hitting screens the same year as Wild Boys, 1933, further advances an endless catalogue of meaning for which no words yet exist. We’re left (fumblingly and woefully after the fact) to describe a rupture. Has the studio system gone stark raving bananas?! Once again, the film’s ostensible agenda is to promote Roosevelt’s economic plan; and, once again, a radical alternative rears its head.

Wellman’s aesthetic constitutes a Dramaturgy of the Crowd. His compositions couldn’t be simpler. I’m reminded of the “grape cluster” method used by anonymous Medieval artists, in which the heads of individual figures seem to emerge from a single shared body, a highly simplified and spiritual mode of constructing space that Arnold Hauser attributes to less bourgeoise societies.

If the mythos of FDR, the man who transformed capitalism, is just that, a story we Americans tell ourselves, then Heroes for Sale represents another kind of storytelling: one firmly rooted to the soiled experience of the period. Amid portrayals of a nation on the skids—thuggish cops, corrupt bankers, and bone-weary war vets (slogging through more rain and mud than they’d ever encountered on the battlefield)—one rather pointed reference to America’s New Deal drags itself from out of the grime. “It’s just common horse sense,” claims a small voice. Will national leadership ever find another spokesman as convincing as the great Richard Barthelmess, that half-whispered deadpan amplified by a fledgling technology, the Vitaphone? After enduring shrapnel to the spine, dependency on morphine, plus a prison stretch, his character Tom Holmes channels the country’s pain; and his catalog of personal miseries—including the sudden death of his young wife—qualifies him as the voice of wisdom when he explains, “It takes more than one sock in the jaw to lick 120 million people.” How did Barthelmess—owner of the flattest murmur in Talking Pictures, a far distance from the gilded oratory of Franklin Roosevelt, manage to sell this shiny chunk of New Deal propaganda?

How did he take the film’s almost-crass reduction of America’s economic cataclysm, that metaphorical sock on the jaw, and make it sound reasonable? Barthelmess was 37 when he made Heroes for Sale; an aging juvenile who less than a decade earlier had been one of Hollywood’s biggest box-office titans. But no matter how smoothly he seemed to have survived the transition, his would always be a screen presence more redolent of the just-passed Silent-era than the strange new world of synchronized sound. And yet, through a delivery rich with nuance for generous listeners and a glum piquancy for everyone else, deeply informed by an awareness of his own fading stardom, his slightly unsettling air of a man jousting with ghosts lends tremendous force to the New Deal line. It echoes and resolves itself in the viewer’s consciousness precisely because it is so eerily plainspoken, as if by some half-grinning somnambulist ordering a ham on rye. Through it we are in the presence of a living compound myth, a crisp monotone that brims with vacillating waves of hope and despair.

Tom is “The Dirty Thirties.” A symbolic figure looming bigger than government promises, towering over Capitalism itself, he’s reduced to just another soldier-cum-hobo by the film’s final reel, having relinquished a small fortune to feed thousands before inevitably going “on the bum.” If he emits wretchedness and self-abnegation, it’s because Tom was originally intended to be an overt stand-in for Jesus Christ—a not-so-gentle savior who attends I.W.W. meetings and participates in the Bonus March, even hurling a riotous brick at the police. These strident scenes, along with “heretical” references to the Nazarene, were ultimately dropped; and yet the explosive political messages remain.

More than anything, these key works in the filmography of William A. Wellman present their viewers with competing visions of freedom; a choice, if you will. One can best be described as a fanciful, yet highly addictive dream of personal comfort — the American Century's corrupted fantasy of escape from toil, tranquility, and a material luxury handed down from the then-dying principalities of Western Europe — on gaudy, if still wondrous, display within the vast corpus of Hollywood's Great Depression wish-list movies. The other is rarely acknowledged, let alone essayed, in American Cinema. There are, as always, reasons for this. It is elusive and ever-inspiring; too primal to be called revolutionary. It is a vision of existential freedom made flesh; being unmoored without being alienated; the idea of personal liberation, not as license to indulge, but as a passport to enter the unending, collective struggle to remake human society into a society fit for human beings.

In one of the boldest examples of this period in American film, the latter vision would manifest itself as a morality play populated by kings and queens of the Commonweal— a creature of the Tammany wilderness, an anarchist nurse, and a gaggle of feral street punks (Dead End Kids before there was a 'Dead End'). Released on June 24, 1933, Archie L. Mayo's The Mayor of Hell stood, not as a standard entry in Warner Bros.’ Social Consciousness ledger, but as an untamed rejoinder to cratering national grief.

by Daniel Riccuito

Special thanks to R.J. Lambert

5 notes

·

View notes