#both the Iliad and the Odyssey? There are scenes of him being a good father in those texts it's not some obscure arcane knowledge.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So final thoughts on the Odyssey. I weirdly enjoyed it wayyyyy more than I thought I would. I NEVER get emotional over reading but I almost cried like, 3 times while reading it. It gets genuinely super tragic. Luckily I didn’t cry otherwise my co-counselors and campers would’ve been weirded out lol. But yeah I greatly enjoyed this story. I didn’t think I’d love Odysseus as much as I did but I adore him! I remember him being an annoying prick but he turned out to be a genuine guy who sacrificed so much to get home and suffered for so many years. And seeing Ithaca suffer while he was gone was also sad.

Like, imagine being Telemachus, growing up with rude men harassing your mother, eating your father’s property and being cruel, and all he can do is sit and let it happen? And then he hears stories about his father who is bold, strong, and powerful, and he feels like he is nothing and can’t do anything to help his mother. And his mother spends her days crying over his father. Like dang, poor Telemachus

But let’s not forget Penelope. That woman cried for her husband and probably barely had any time to mourn for him. She’s pressured to marry the douchebags disrespecting her and deals with maids betraying her and making things worse. Her mother in law dies and everything goes wrong, like that poor lady.

And of course… freaking Odysseus…. That man… Homer loved to torture him. He went through so much crap for 20 years, but it’s satisfying to see it all turn out good in the end for him. He’s able to be with his wife and son finally.

I absolutely adore how similar Penelope and Odysseus are. Both are very cunning and lie to people a lot. But they never lie to each other. The scene where they’re just talking to each other and sharing their time away from each other was SO tender. I said this before but the fact that one little scene of the two together had more chemistry than a flipping chemistry class is insane. They’re in love, so much in love. And augh…. They were so faithful to each other. I also love how they cried so many tears for each other. GOSH I love them sm.

And Telemachus is my son. I’m sorry he is. I’ve adopted him. He’s so cute

But yeah, I wanna read the Iliad now! Wanna see more details. I found it interesting that a lot of people, including Penelope seemed to hate Helen, who I believe was kidnapped by the Trojans which started the war. Pretty crazy, but I’ll find out more details about it.

#yeah I’m not gonna be normal about this sorry guys#I was goin feral#smiles rambles#SO GOOD#AND SO AMAZING!!!!!#tho the ending was super abrupt#I would’ve liked a more solid ending#but this was Ancient Greek times#oh well#but yeah more Penelope and Odysseus stuff pls and thank you#I adore them so much#smiles reads the odyssey

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

SECOND HALF in which the entire trojan war gets admirably shortened to about three songs

also closing thoughts about the entire thing

i was SO excited for hector having a song of his own but 'no turning back' is not the kind of song i wanted for him

it is really sexy that the trojan choir has both female and male members though, especially when they go "death to our enemies"

okay NOW there's a timeskip, haha. i was wondering how this would unfold. it feels very abrupt though. "oh god the greeks are gonna attack us" and then "well here we are ten years later, agamemnon what the hell are you doing with achilles' slave girl"

i wonder how in the weeds we're gonna get about achilles and agamemnon when this is paris' story

okay that is a fairly efficiently pared down version of the conflict, actually. briseis never gets mentioned by name but at least it conveys that achilles is fed up with agamemnon's leadership

hoho i LOVE the gentle emotion in quast's voice singing the line "agamemnon you divide us all / with your bitching and brooding"

i like patroclus having a point of view song about his feelings. "oh achilles the blood-stained killer... am i a part of you? are you a part of me?"

but then patroclus has to make it weird calling him "my sometimes father / my sometimes son" just guys being related dudes

i wish the guy cast as achilles could sound sad. but fine, he is SUPREMELY creepy and intimidating in all his non-emotional scenes, it's a tradeoff

OH AND ACHILLES AND HECTOR ARE ALREADY ABOUT TO DUEL. shit did we just do almost the entirety of the iliad in two songs. that IS efficient!

wait so if hector's about to die did they actually NOT do the "hector yells at paris for not being on the battlefield" scene?? in the paris-centered musical??

oh my GOD what IS hector's power ballad about love at THIS point in the narrative. "it's better to love and lose than to never love at all". is he singing that to andromache?? yeah like THAT'S the moral of hector's story...!

paris' shocked "you murdering BASTARD" at achilles is so funny. paris everyone's been fighting a war for ten years because you won't give up someone else's wife. everybody been murdering bastards for some time now

achilles at paris: "you may be good with women, boy / but you're no match for me" 🤨

ohhh so in this version paris asks aphrodite to preserve hectors corpse AND to guide his aim to kill achilles. which is narratively efficient but it bums me out that there is exactly one god in this entire trojan war

fuck YES the ulysses-in-disguise scene is a waltz. i go bananas whenever moments of deception are conveyed in 3/4

ulysses is so at a loss he prays to athena. ladies and gentlemen a second god has entered the trojan war!!

ULYSSES AGREES TO BECOME A HEAD WITHOUT A HEART!! he trades his happiness for athena to help him find a way to end the war. that is a very new direction to take the wooden horse and the odyssey but tbh i'm kinda into it

"we need to find a stooge / a fool / sinon, you're perfect!" "whuh?" KILLED ME

'inside outside' is awful and it just KEEPS GOING. WE GET IT YOU'RE DRUNK AND BURPING. NOT THE ENCORE. PLEASSSSE.

okay NOW helen finally says she loves paris, she's sounded very noncommittal and kinda humoring him about it up to this point honestly

oh and then there's a reprise of hector's love power ballad. THIS DOESN'T FEEL LIKE SOMETHING COMING FULL CIRCLE. WHY WAS IT HECTOR'S SONG TO BEGIN WITH AND ALSO HE SANG THAT LIKE. ONLY FOUR SONGS AGO

AND IT'S DONE.

okay yeah okay. i still think a good portion of the music is GREAT. digging the performances. and i have to remind myself it's a concept album because narratively it's kinda... there are some very unbalanced elements here. the complicated plot of the iliad is impressively pared down but then it kinda fails to focus back in on paris, he's missing through most of the second half, and ulysses takes over the protagonist role. also the whole "love conquers all" thing doesn't really work when it provably doesn't conquer anything on this occasion.

secondly, paris doesn't grow at all. he doesn't acknowledge his fault in the war, he doesn't acknowledge his fault in hector's death. he doesn't look back at the end and think about the things he's been through. it's just "i'll always love you mwah mwah. okay i'mma die now".

i'm still gonna listen to my favourite songs a billion times.

alright paris the musical liveblog let's gooooooo

FIRST HALF! watch me lose all principles whenever i think a melody is nice

like idk man the poster for this gives me that HE ONLY DID IT FOR LOVE thing with paris that doesn't appeal to me, that's why i haven't checked it out before. i feel they're gonna turn him into a hapless but sympathetic hero. bet there won't be an oenone. but here we go

IT'S SO EIGHTIES. I DIDN'T KNOW IT WAS THIS EIGHTIES. oh this is good actually

when homer (!) is dramatically presenting all the main players, in my mind i can't help but see them strike sassy poses as the spotlights hit them, their sequins flashing. "agamemnon! of mycenea!"

"ulysses! of ithaca! / longs for peace and security" i don't know if i like that as the main trait he's introduced with but okay let's see how he works in this paris-centered narrative

'head without a heart' IS SO GOOD. ohh it's just the kind of eighties' vibe i like.

oh this this framing might place the blame of the trojan war more at paris' feet than helen's, which i like, but also that he's just a stupid youngster, and that's interesting too: "Not some mad messiah of destruction and fire / Just a lovestruck youth"

ohhh and i LOVE paris interacting directly with cassandra! he never seems to do that in any adaptations. "Sister, please don't grieve / I've learned my part to the letter"

'straight ahead': HOLY SHIT GET HYPE. it's so extremely "cool protagonist is finally gonna live his life" opening number. it's weird to have paris be that kind of protagonist. but also it makes me think about how this poor shepherd boy was the WORST guy to make an ambassador, like cassandra IS right about that.

ugh i don't like when they put the weird histrionic plot stuff in the middle of a cool-ass song.

i'm dying at the others screaming at paris while he's like "the sea and sky :D my friends and i :D what could go wrong, what could -AAAAAAAAHHHH!!!"

paris falls in love with helen at first sight and assumes she's aphrodite. does aeneas know paris is weird about his mom. oh my god i just realized EVERYBODY'S weird about aeneas' mom, that's gotta be exhausting for him

"i married young, in love with power" oh it's one of those where helen's unhappily married. sigh. okay.

OH the way 'business' takes off after agamemnon's evil laugh. i'm appalled at the characterization but i'm just gonna have to roll with it because the music in this thing rocks

THERE HE IS! QUAST-PATROCLUS. who's like "ummmmm wHY are we having a meeting without my bestie achilles here"

OHH AGAMEMNON TRICKED ACHILLES SO HE WOULDN'T APPEAR AND BE VOTED COMMANDER. okay if we're doing evil agamemnon at least he's clever

oh this is a rum tum tugger-ass achilles omg. ohh i hate this but it's so funny. weakest character song so far

ahahaaa ulysses looking at paris' rags and telling him "To gain entry by disguise is an excellent ploy / I shall remember that, prince of Troy"

i enjoy helen being kinda exhausted by the whole thing. "Stop your adoration, I don’t need complications / I'm not a goddess, I am king Menelaus’ wife"

evil agamemnon using the abduction for his own political gain. hm. that makes sense actually (as long as he's evil i mean)

oh now 'thief in the night' establishes that menelaus really loves helen, i didn't expect that from this kind of framing. how is this gonna end now

HELEN HAS SUDDENLY KILLED SOMEONE? WHAT HAPPENED BETWEEN SONGS??

"I love her / I believe she loves me" I WISH SOMEONE WOULD ASK HER. I THINK IT WOULD BE GOOD TO MAKE SURE.

jon english who wrote this also plays hector and does NOT give himself enough songs to go ham on, god his voice is so good when he's PUSHING IT

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

things people who haven’t read/studied the homeric poems should know

the iliad isn’t about ten years of war. it’s about fifty-one days from the last year of war. more than nine years have passed since the beginning. neither the recruit of achilles or odysseus nor aulis nor the sacrifice of iphigenia nor the trojan horse and not even achilles’ death feature in it. it actually ends with hector’s burial.

similarly, the odyssey starts during the tenth year of odysseus’ travels, when he leaves the island of the nymph calypso who had kept him there for eight years. while the story of his travels is actually there, it’s a massive flashback that odysseus himself narrates.

odysseus actually only travels circa one year, if you subtract the seven years spent on ogigia, the one year with circe, the various months and bits they camped in other places.

part of the odyssey is actually about odysseus’ son, telemachos, and his quest to find his father. also another part is about odysseus returning to ithaca and killing a bunch of princes who were trying to usurp his throne.

the aeneid is not a homeric poem. it’s styled on the homeric model, but it was written in latin by a roman poet, and the protagonist is technically one of the antagonists from the iliad.

homer never existed.

he isn’t a historical figure, he is a name with a legend attached, to whom these poems are attributed. the poems were written—no, not even written, composed orally by a series of unnamed aoidoi (hm... ministrels?) through the ages.

in fact this is quite obvious when you read the iliad. there are a lot of inconsistencies, like frequent style changes, chapters that have nothing to do with anything else and no influence on the story whatsoever, strange time lapses—at some point it’s midday twice the same day

it is thought that all of these separate fragments were then collected and organized by one person, and this version was then handed down, orally, until the first written edition around 520 b.c.

the mycenean civilization that these poems originate from ended in 1200 b.c. circa

the odyssey was initially part of a whole group of nestoi, aka “return poems”, that were basically the tales of the return of each hero from troy. the odyssey is the only one that remains, though we do know something about the others too from other pieces of greek literature

a warning for the interested. these poems are a pain to read. they are delightful but they are a pain. they were composed orally so they are full of epithets, descriptions, metaphors and similitudes. these acted as fillers to help the aedo of turn reach the length of the verse, make the various characters more recognizable, and also make the poems more comprehensible to the general public, composed mostly of common people who had never actually been in a battle—so battles and duels are often compared to more familiar scenes, like fights between animals.

no i’m not joking

there is one in particular where the screeching army of trojans coming down the hill is compared to cranes migrating over the oceans.

also, the duel between hector and patroclus is one of the “compared to animal fights” scene

when odysseus is about to drown, he talks to his own heart. possibly because it sounds slightly less crazy and more Romantic than just directly talking to oneself.

helen insults paris real often. hector berates him both internally and publicly. in fact everyone insults paris. paris is the local coward and scapegoat. deservedly. i rejoice

everybody loves patroclus. all the kings hate each other but everyone loves him—so much so that they risk their lives over his corpse

which, mind me, wasn’t something that special in and of itself. it was important to retrieve comrades’ corpses because if the enemy got ahold of your body he’d leave it to rot and be devoured by dogs and crows, which was a huge dishonour (and also possibly barred you from entrance to the afterlife)

so much so that the ancient greek version of “go to hell” is eis korakas, “to the crows” (“may you die, lie unburied, and your body be eaten by crows”)

at some point they hold a truce (possibly several times) so they’ll have the time to collect, burn and bury all the fallen soldiers.

back to patroclus because i got sidetracked: still. this time it is kind of a big deal because the literal centre of the fighting after patroclus dies is all the major greek heroes playing tug-o-war against hector and his brothers with patroclus’ corpse. the centre of the fighting, people, this is no joke

at some point someone is sent to tell achilles that his lover’s body is in danger so he better get out of your sulk, hurry up and come help the rest of us

achilles going armour-less to the battlefield and screaming for patroclus is enough to send the trojans running.

i am sure that all of you know this but the reason achilles doesn’t have armour is that when hector kills patroclus he takes achilles’ armour, that patroclus was wearing, as spoils of war

so an entire book after that is devoted to hephaestus forging achilles new, better armour so he can actually fight again

look, it is not actually stated that they were lovers, but it’s obvious. in greek culture especially. that was the norm and italian school teachers can get over it and stop omitting it from lessons and school books any time now

odysseus isn’t actually an asshole. sure, a lot of his misadventures were caused by him being too curious and disregarding his comrades’ advice *cough*cyclops*cough* but most of the most destructive events were caused by them disregarding his orders.

“do not kill and eat the sacred cows of apollo! he’d kill us.” guess what they did. guess how it ended

or when they stopped by eolos’ island. eolos, god of the winds, gave odysseus a flask with all the adverse winds imprisoned inside, leaving free only the one that he needed to take him to ithaca. they got so, so very near, and then odysseus fell asleep and the others opened the thing because they thought there was more treasure inside it, and all the winds came out and blew them halfway across the mediterranean

athena often glamours odysseus to look younger and prettier or older and then again younger. it’s amazing because he always looks either like an old beggar (for camouflage) or like a young and handsome man.

do some maths. at the beginning of the war he must’ve been at least twenty. + ten years of war. + ten years of travel. at the end of the odyssey he is at least forty. by ancient standards that was not young.

odysseus’ whole voyage is basically a pissing contest between poseidon and athena. actually between poseidon and the rest of the gods. poseidon hates him and all the other gods take turns helping him.

odysseus is not an asshole, but the greeks probably considered him a shitty character, because he was clever, shrewd, and the only survivor of his community. the greeks really insisted on the concept of community, the individual doesn’t have worth in and of themself but as a part of society. this is particularly evident when he gets to the cyclops, who are the very antithesis of the greek man, described as uncivilized and living in isolation without assemblies or laws. a lot of emphasis is put on the fact that they live outside of a community.

alternatively, the difference between the iliad and the odyssey (and their respective heroes) signifies the change in greek culture, from the warrior myceneans to commerce and voyage: odysseus represents the victory of intelligence over force, and his qualities are the characteristics, for example, of a merchant

i should perhaps point out that the odyssey was composed much later than the iliad, which is also the reason it has a more complex structure (begins with the gods + telemachos’ quest, we first see odysseus on ogigia, then he recounts his whole voyage in a long flashback triggered by a bard at a feast singing about the trojan war)

oh look i got sidetracked again

back to the trivia!

do not be fooled by madeline miller. patroclus was indeed a warrior, and a very good one at that. and briseis was indeed achilles’ lover, and loved him (that is explicitly stated).

odysseus might have loved penelope but that does not mean he did not sleep around with every woman he met

circe. calypso (by whom he is imprisoned for seven years). and nausicaa princess of the phaeacians falls in love with him. this is engineered by athena

i don’t think he actually sleeps with her but athena does make him look younger and prettier so she’ll be smitten and welcome him at the palace and give him a bunch of gifts and eventually a ship to take him back to ithaca

in the poem named after him, his own poem, odysseus is always the stranger, the guest, or the beggar.

or all three.

or all three, but it’s a lie and he’s actually at home, the king returned.

despite the iliad being about one and a half months and the odyssey being more than a year + more time taken up by other characters, the iliad is about one and a half times the odyssey.

more to come (maybe)

#if i can think of anything else#eden rambles#iliad#odyssey#homer#this is half actual stuff i learned in class half things i find funny

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

madeline miller’s ‘the song of achilles’

Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1855) by Nikolai Ge

What I loved about The Song of Achilles: this and this and this.

My interest in classics began circa 2005, with Disney’s animated series based off of their rendition of Hercules. Fast forward to several years later, to when I stumbled across one of my grandad’s books; several of my rose-tinted childhood memories would be tainted by the knowledge that the actual Heracles had very little in common with Disney’s adaptation of him.

The historical period that I was really invested in for most of my preteen and early teenage years were the Dark Ages, and Medieval Europe in general; so my Greek mythology phase was short-lived, and my knowledge of it is… well, I know Dionysus fucked himself with a wooden dildo to fulfil a promise he made, and that he’s perhaps the only decent bloke up there on Olympus (I’d tell Zeus to go fuck himself but he’d probably go through with it), and also that Dionysus is BTS’s best song since Boy Meets Evil, and that Stray Kids did a bangin’ cover of it late last year.

In other words: vague and superficial.

But I know enough to tell you that Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles is one of the best books I’ve ever read, hands down.

The story of Achilles and Patroclus and the Trojan War is pretty common knowledge, I’ll warrant, but just in case: SPOILERS AHEAD.

Retelling a story almost everyone knows isn’t easy; you’ve got the plot down and how to get there, but you’ve got to write it in a way that doesn’t read like a middle school book report you scrapped together a night before the assignment was due (… not that I know what that’s like, haha). And Miller does an excellent job of it; her diction? Brilliant. Her prose? Incredible. Her characterizations? Completely not ever been done before.

The Song of Achilles is told in Patroclus’s first-person point of view; most of it is about his early years with Achilles; Patroclus’s banishment to Phthia, meeting Achilles, befriending Achilles, and then both of them being tutored by Chiron (a far cry from Disney’s funny little goat man). The Trojan War takes up less of the book than I thought it would, at first (which, of course, I’m infinitely grateful for- since we all know how THAT ends) (#RIP).

Which brings me to one of the biggest questions I had up to the last few chapters before the end of the book: how will the story go on after Patroclus dies, since it’s in the first person? (The first-person POV threw me off at first; it’s been a while outside of contemporary YA that I’ve read anything in that POV, and it was a bit jarring- but the further I read, I realized that it was the best option for the book; it gave the story a depth, a level of emotion you couldn’t’ve achieved in the third person.)

And call me a masochist, but Patroclus’s death and the aftermath ended up being my favorite parts of the book. I’ve read stories that have given me actual, physical pain (one of my top two Harry Potter ships is Wolfstar, go figure), but this is the first time I’ve actually read something that made me cry (despite the numerous Ao3 comments I’ve left that are variants of ‘omg I’m crying’). Like, actual, physical tears welling up in my eyes.

There’s this particular scene, in the ninth chapter, where Chiron is telling Patroclus and Achilles about Heracles, and how he, unlike Disney’s well-intentioned, bumbling himbo, goes insane and kills his family. Achilles, my sweet summer child, is quite reasonably agitated by this; how it was unfair, how Heracles’ wife and children paid for the gods’ tiff with Heracles with their own lives. And Chiron says:

“… Perhaps it is he greater grief, after all, to be left on earth when another is gone.”

Go ahead, Miller; twist the goddamn knife. It’s not like I needed my heart, anyway.

Also, unrelated, but I find it interesting how countries that are continents apart end up having quite similar legends. My roots are from an entirely different continent than Greece, but we have a folktale quite similar to the legend of Aesclepius.

But I digress.

Character-wise: Achilles; half-mortal, hero of the Trojan war, the greatest warrior among men. And despite his demigod status, he remains so human. And this might be controversial, but… he comes off a lot more fleshed-out than Patroclus himself. Which is perhaps my sole gripe with this book.

Patroclus is… well, he exists. He’s the son his father never wanted. He kills a boy. Falls in love with Achilles. Spends a concerning amount of time describing Achilles’ feet.

Honestly, up until the chapters in Troy, he doesn’t have much of a personality. And maybe it’s because Miller wanted to remain as true to the Iliad and Odyssey, and, if my memory serves me correct, neither of them give a lot to Patroclus in the way of character development; but still, he comes off a bit- bland. Of course, towards the end, his character gets a bigger role than ‘loves Achilles’; especially seen in how he defies Achilles to spare Briseis, and then dons the armor and subsequently gets himself killed (#ApolloIsOverParty), but up till then, he’s pretty meh.

Briseis is another one of my favorite characters; it was a bit difficult for me to divorce my perception of her from Emily Hauser’s For the Most Beautiful. Her friendship with Patroclus (and, by extension, Achilles; even if he did screw her over afterwards) was perhaps the only good to come out of the war.

And then we have the obligatory: fuck Thetis and FUCK Agamemnon (thank you, Clytemnestra).

Achilles and Patroclus’ love was wonderfully written, and I love how them being queer wasn’t the central focus of the story (admittedly, the ancient Greeks were markedly more casual about homosexuality than the bible-belt world we live in today). A lot of the (non-fanfiction) queer lit I’ve read tends to make everything revolve around, “bUt I aM bOy,,, aNd I LiKe bOy,,, bUT hOW???”, and homophobia is the biggest obstacle to their relationship. And those stories are realistic and need to be told- but we need literature with more variety.

My final verdict: a work of art. I’m going to read Circe and Galatea.

#achilles#patroclus#the song of achilles#madeline miller#greek poetry#iliad#homer's iliad#odysseus#homer's odyssey#odyssey#lgbt#LGBT literature#lgbt fiction#lgbtq#book review#historical fiction#greek myth#greek myth retellings

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Amber and Clay by Laura Amy Schlitz & Julia Iredale (2021)

(Full disclosure: I received a free ARC for review through Edelweiss and Library Thing's Early Reviewers program. Content warning for child abuse, animal abuse, and sexual assault.)

The children I spoke of before were like that. They weren’t alike, but they fit together, like lock and key. The boy, Rhaskos, was a slave boy. Unlucky at first. A Thracian boy—(Thrace is north of Greece) —redheaded, nervy, neglected. A clever boy who was taught he was stupid. A beautiful boy whose mother scarred him with a knife. The girl, Melisto, started life lucky. A rich man’s daughter, and a proper Greek. Owl-eyed Melisto: a born fighter, prone to tantrums, hating the loom. A wild girl, chosen by Artemis, and lucky, as I said before— except for one thing: she died young. This is their story. When it's over, if you like, you can tell me what it means.

"I want to tell you the things I never told anyone, in case this is my last chance. When I was alive, I didn’t talk much. So much of what I felt was a secret. I think that’s what I loved about the bear. Neither of us had any words."

Again we walked and talked. I never talked to anyone like that. No one ever talked like that to me. I talk to you still, Melisto. I’ve been talking to you ever since.

The red-haired boy variously known as Rhaskos, Thrax, and Pyrrhos is many things, though few of his masters care to know. He's Thracian nobility, with the scars to prove it - and also a slave, belonging to the wealthy Alexidemus and his soldier son Menon in Thessaly, and then to a humble potter named Phaistus in Athens. He loves horses and is as adept at handling them as he will one day become at drawing and sculpting them. He is a contemporary and friend of Sokrates, though he is powerless to stop his execution. He is an orphan, with a dolphin for a mother; a mother who loves him so fiercely that she curses a ghost to help set him free. He is like clay: common at first glance, but also not; capable of transmuting into creations lovely, clever, and full of value.

The owl-eyed girl called Melisto is seemingly as lucky as Rhaskos is not: the only child of a wealthy Athenian, Melisto wants for nothing. But she is a wild (read: untamed) girl child in a rigidly gendered society that has already predetermined Melisto's future for her: marriage, motherhood, a life of quiet domesticity. When, at the age of ten, Melisto is chosen to serve the goddess Athena as a Little Bear, her life opens up before her at Brauron; this is who she was meant to be. Like all good things, it cannot last.

Rhaskos and Melisto's destinies collide when Melisto frees a bear cub that is to be sacrificed to Athena. Or maybe their paths met even earlier, when Meda/Thratta was ripped from her toddler son. Perhaps the gods nudged them towards each other from birth. Alternately, the gods have nothing to do with it. Who can say? (Hermes, maybe. He has a lot to say and loves to hear himself talk!)

AMBER AND CLAY is ... not what I expected. Normally I'd steer clear of a contemporary (or any!) book styled after the ancient, epic poems (I positively labored through THE ODYSSEY and THE ILIAD in high school!), but the visual element sucked me in. I was under the (mistaken!) impression that AMBER AND CLAY would be heavier in illustrations than it actually is, almost as though part graphic novel. As it turns out, the illustrations - of archaeological artifacts - are a little sparser than I hoped, but they tie into the narrative quite nicely and add another layer of wonder and surprise to the story. The "exhibits" are really well done and do not disappoint.

Additionally, the synopsis had me thinking that this would be a supernatural romance; and while AMBER AND CLAY is indeed a love story, Rhaskos and Melisto are entirely too young to hook up, even by the time they finally meet near the story's end. (It's hard not to envision them - especially Rhaskos - as older than they are, both because the story seemingly stretching across years, and so much happens to these crazy kids to last several lifetimes.) Instead, this is a different kind of love story: AMBER AND CLAY tells of the love between a mother and her son; a father and his daughter; a teacher and his students; a girl and a bear; a ghost and her tether to the earth.

And despite my reservations about those epic poems, Schlitz both honors the form and breathes new life into it. While Melisto tells her story in prose, Rhaskos speaks in verse; and the gods sometimes address us commoners in turn-counterturn, occasionally using more complicated linguistic techniques like elegian couplets (which I barely recollect from HS English). This all sounds incredibly tricky and complicated (and undoubtedly is), but Schlitz pulls it off without a hitch. AMBER AND CLAY is fun and engaging, with a surprising sense of humor and expert sense of dramatic flair.

“Oh, Phaistus, look at his hair! He’ll be beautiful once he’s healed. We’ll call him Pyrrhos!” As if I were a dog. Pyrrhos means fiery. Half the red-haired slaves in Athens are called Pyrrhos.

It is, dare I say, exceedingly readable.

Honestly, I let out a little groan when I saw the "Cast of Characters" on page one, complete with various households and multiple monikers for the same people; but the story, the characters, their relationships to one another - all are easy enough to follow.

Schlitz's characters, both those based on historical figures and those spun from imagination and whimsy, are so full of life that they practically jump off the page. Rhaskos and Melisto; Meda and Lysandra; Phaistus and Zosima; Menon and Lykos; and, of course, Sokrates. Likewise, her descriptions of Greek life and customs left me hungering to learn more. Naturally, the most fascinating custom - that of the Little Bears of Brauron - is also that which we know the least about.

The scenes featuring Melisto and the bear cub are among my favorite in the book. In a story filled with animal sacrifice, this little slice of compassion and respect is life-affirming; to wit:

It turned in slow circles and collapsed with its rump pressed against her thigh. Melisto put one hand on it. It seemed to her that she had never touched anything more real than the bear cub.

For a moment her mind slipped back into the past. She recalled the bruises she had carried from her mother’s pinches, and the sore patches on her scalp from Lysandra’s hair-pulling. She remembered the loathing in her mother’s face that struck terror into her soul. She had never been afraid of the bear like that.

and

On the nights when she waded into the bay and watched the moon, she was barely conscious of the fact that it was she who saw, and the moon that was being watched. In the same way, she did not measure how much she loved the bear. She was the bear.

Likewise, Rhaskos's interactions with Grau/Phoibe are so wonderfully tender, my heart aches just to think back on them. From the moment he renames her (grau means hag) - a change of name that's much more respectful than those Rhaskos was forced to accept - Rhaskos treats his donkey charge with decency and kindness. The same kindness that he himself longs for.

Animals know when things get better. People might not know, but animals do. That very first day, Grau knew I was going to be good to her and I swear to you, she was glad.

Cue the "what is this salty discharge" gifs.

AMBER AND CLAY is such a beautiful story, and I'm glad I took a chance on it. Iambic pentameter be damned.

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/3861642614

#books#reviews#amber and clay#fiction#historical fiction#Laura Amy Schlitz#Julia Iredale#ancient greece#novels in verse#ghosts#animal sacrifice#child abuse

1 note

·

View note

Text

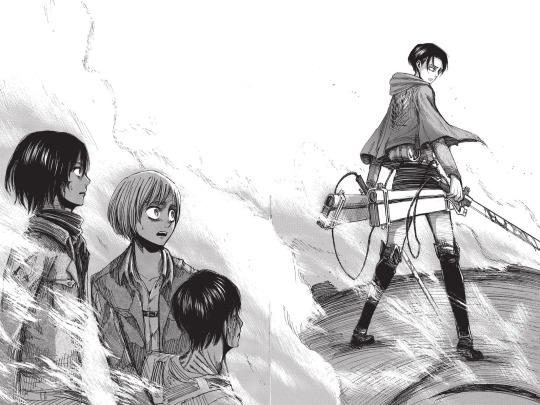

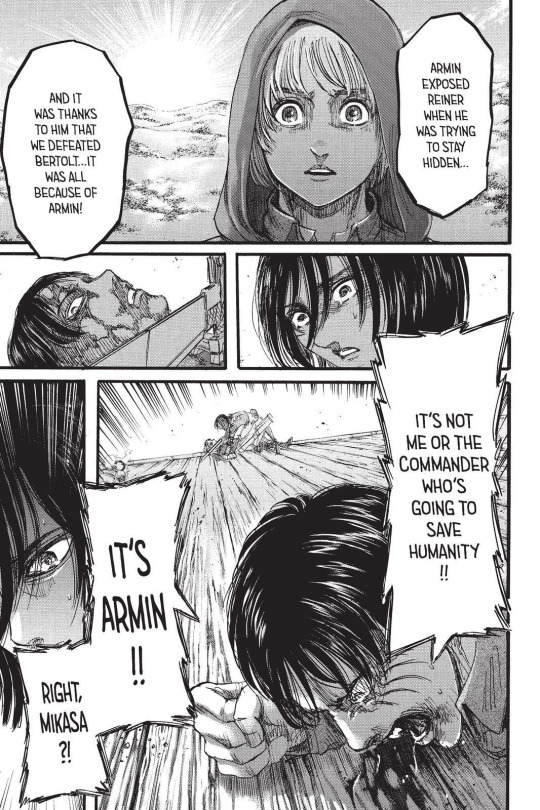

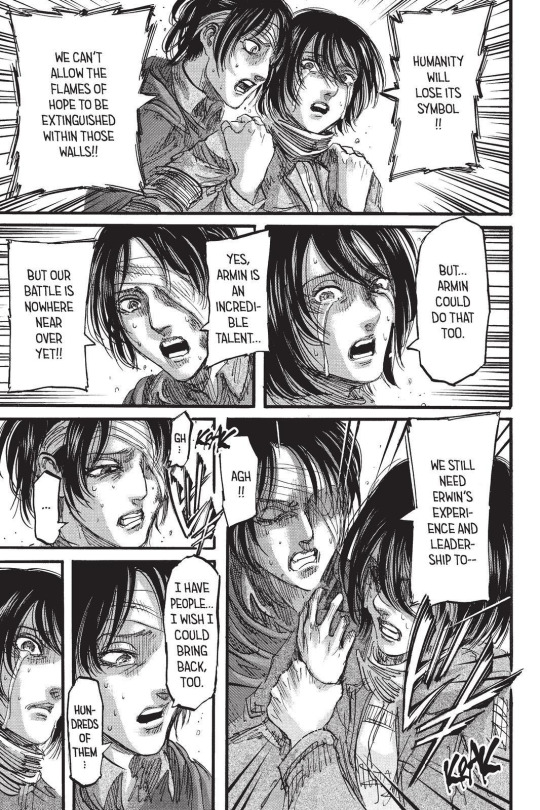

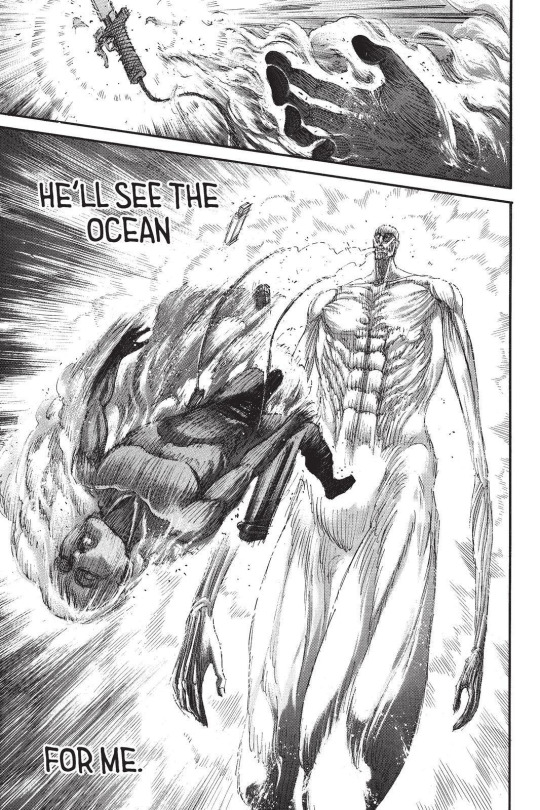

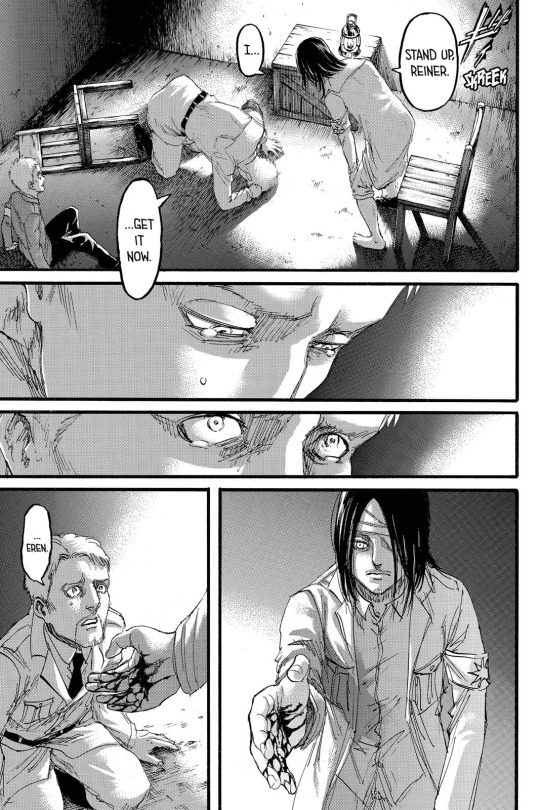

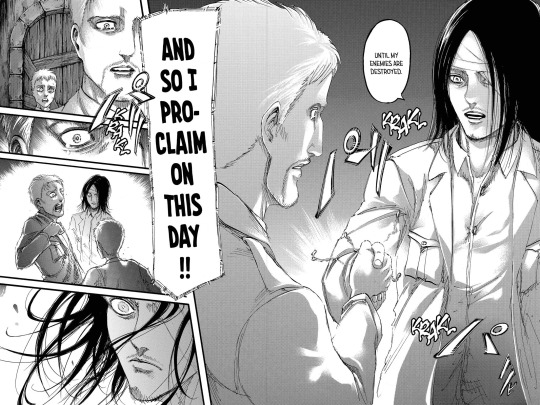

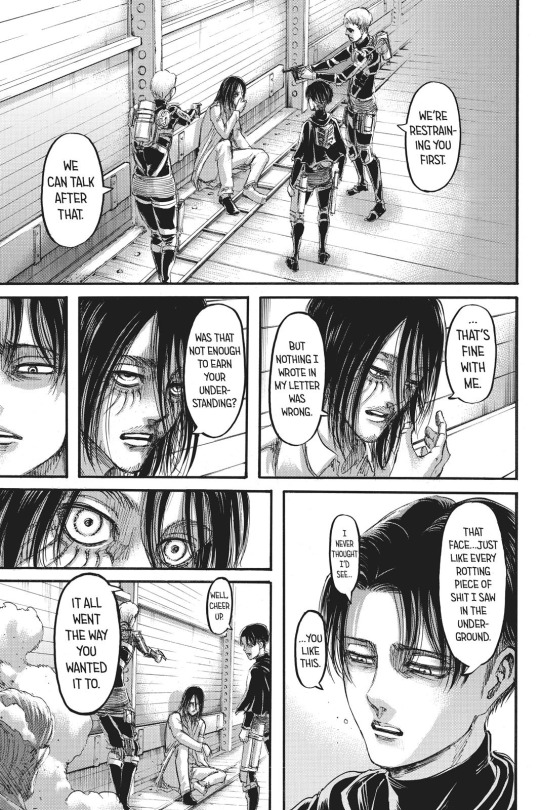

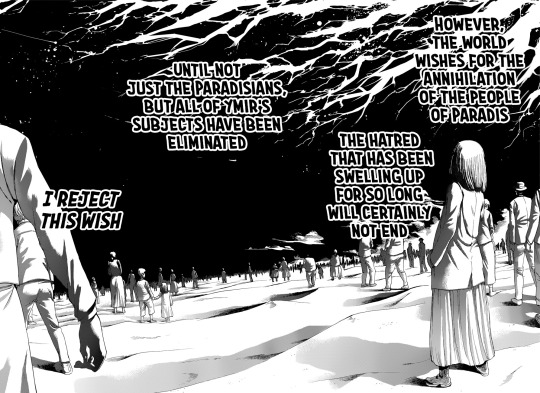

The World is Cruel, Beautiful, and Chiastic

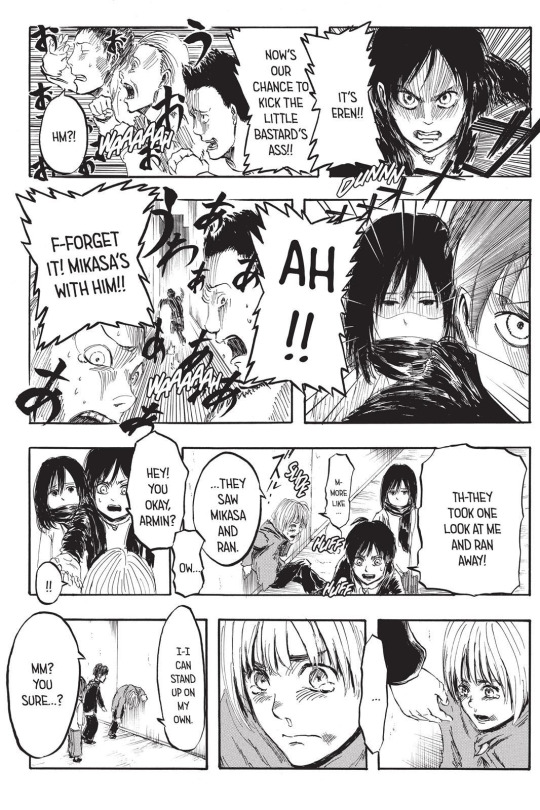

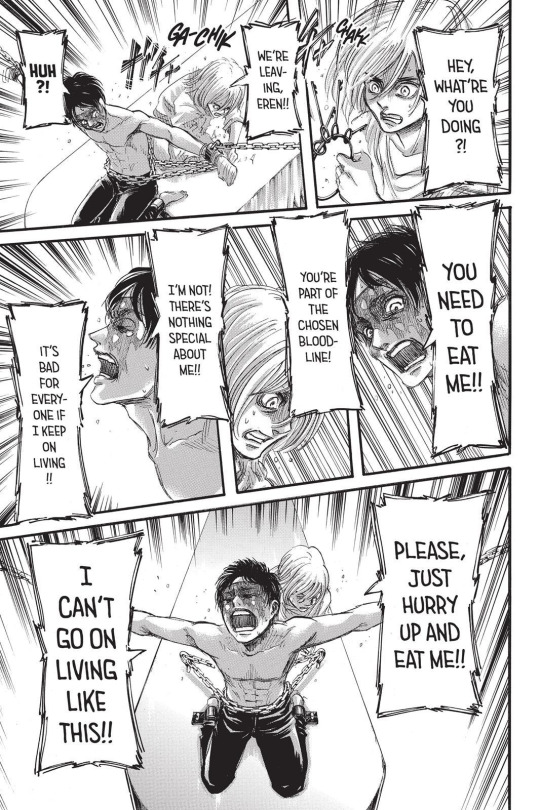

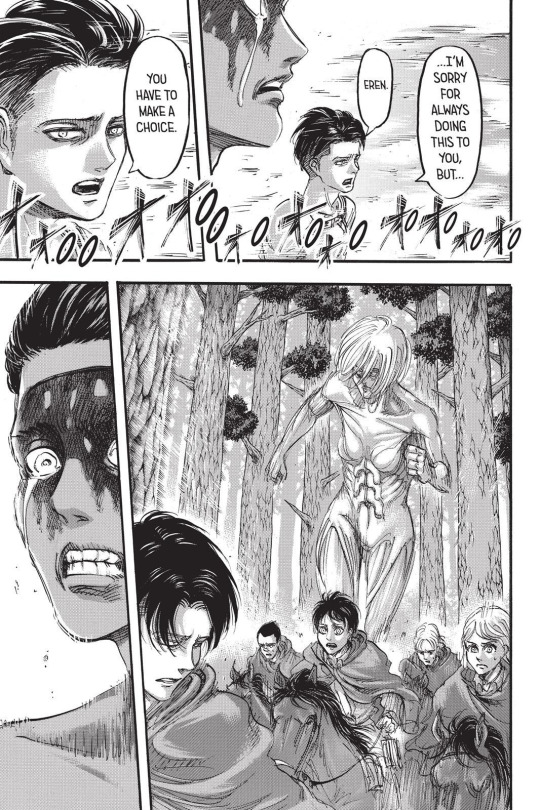

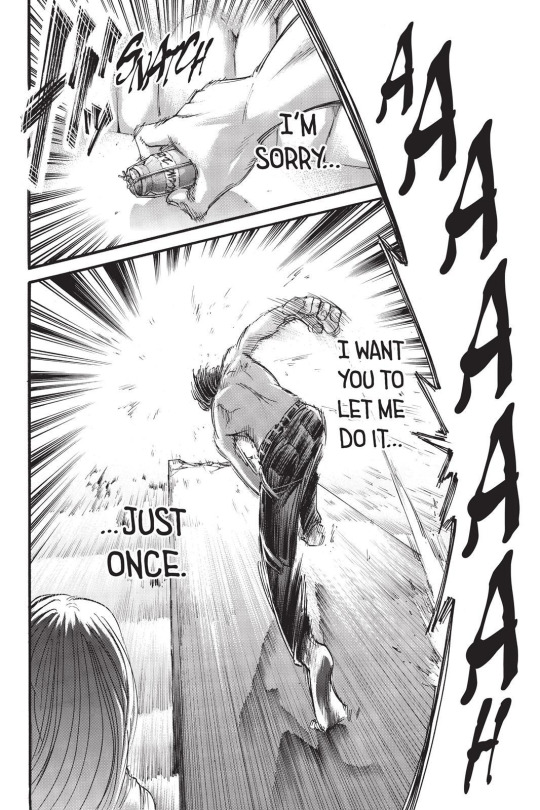

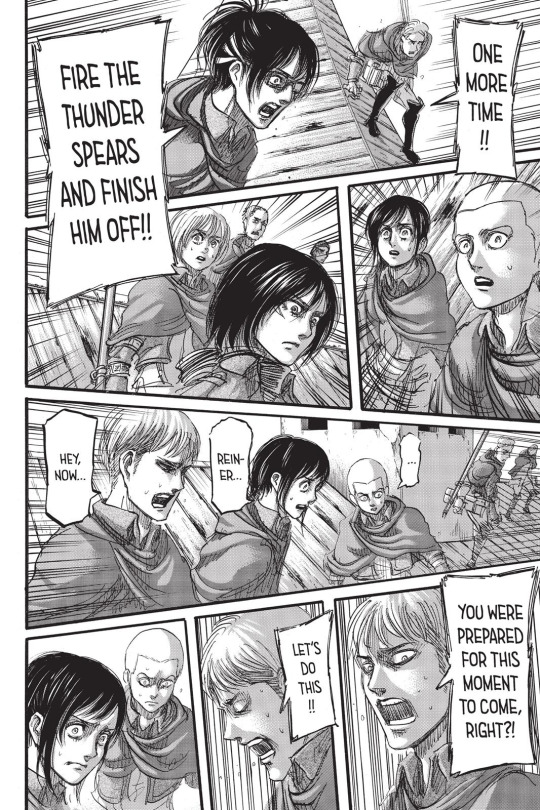

Or, because I see people talking about this and I wrote this during Tokyo Ghoul:re’s final arc (which ended up being accurate), I wanted to be a nerd and outline just what Shingeki no Kyojin’s chiastic structure is.

A chiastic structure is a narrative structure used for millennia in storytelling. It refers to a paralleling structure, wherein events or motifs parallel other events and motifs. If you chart it out, it forms a chiasm or a ring (depending on if you feel like charting a triangle or a circle. (It’s also referred to as ring structure if you go with the latter; hence “come full circle.”)

Chiastic structure has been used for ancient epics (the Iliad and Odyssey, Paradise Lost), religious texts (many narrative books of the Bible, including Ruth, Jonah, Samuel, Genesis, and the Synoptic Gospels use it), and modern classics in both literature and cinema like Harry Potter and Star Wars employ it. In anime/manga, Tokyo Ghoul used it, and Bungou Stray Dogs strongly appears to be using it (but it’s harder to say definitively or to chart it out because we seem to be in upwards end of the middle arc right about now).

So, what’s SnK’s chiastic structure?

A) Fall of Shiganshina: The World is Cruel (and beautiful)

B) Training Corps (yes, it belongs here): Cruelty to Children

A) Trost: Cruel Loss, Beautiful Hope

C) Female Titan: Cruel End to Friendship

ABC) Clash of the Titans: The World is Cruel and Beautiful

C) Uprising Arc: Beautiful Beginning to Friendship

A) Return to Shiganshina: Cruel Loss, Beautiful Hope

B) Marlay: Cruelty to Children

A) Final Arc: The World is Beautiful (and cruel)

Of note, this is not me saying that none of the other arcs parallel each other--they clearly do. This is just a look at the chiastic structure in particular.

A note about the AB pattern. Arcs that have A all have common elements even if they most directly parallel the arc they line up with. The central chiasm contains elements of all three.

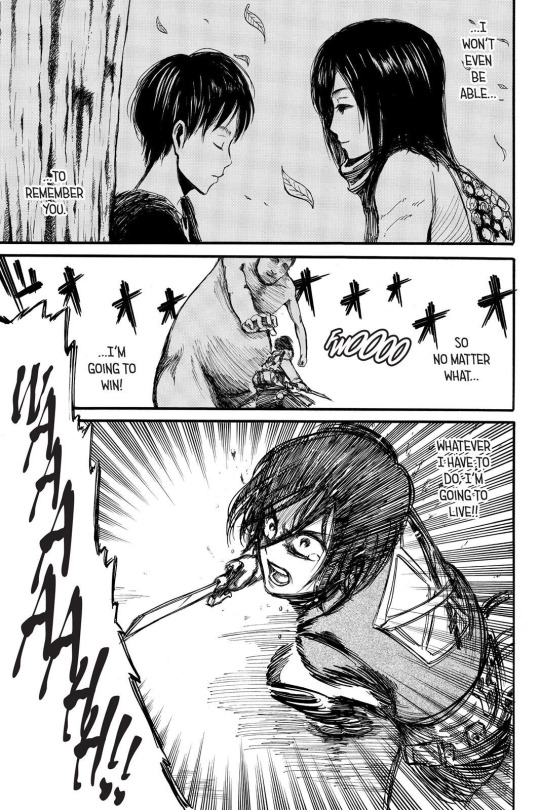

Fall of Shiganshina Arc: The World is Cruel (and also beautiful)

I’m not sure I need to say much here lol. The story’s opening chapters are renowned for their horror and display of cruelty. Yet we see beauty too in the Jaeger family having taken in Mikasa, in Eren defending Armin from bullies.

And we see it in how Hannes saves Eren and Mikasa.

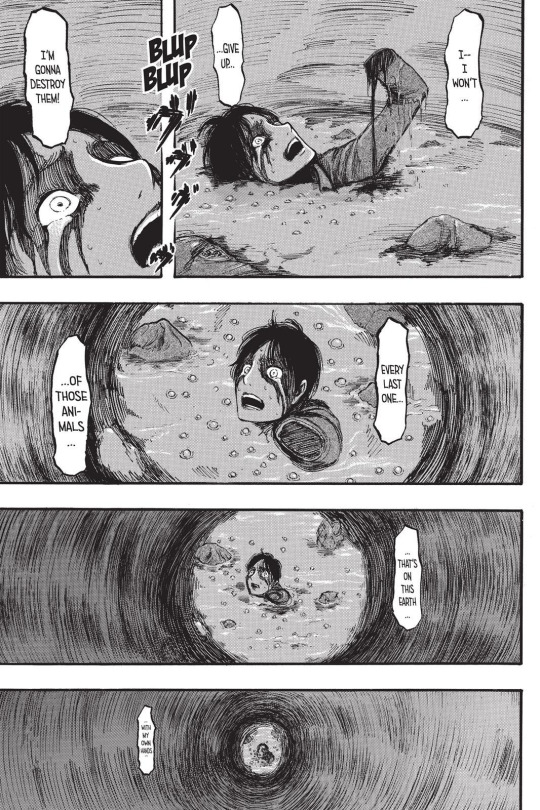

And there’s more cruelty in the vow Eren makes, which, of course, he’s now bringing to fruition:

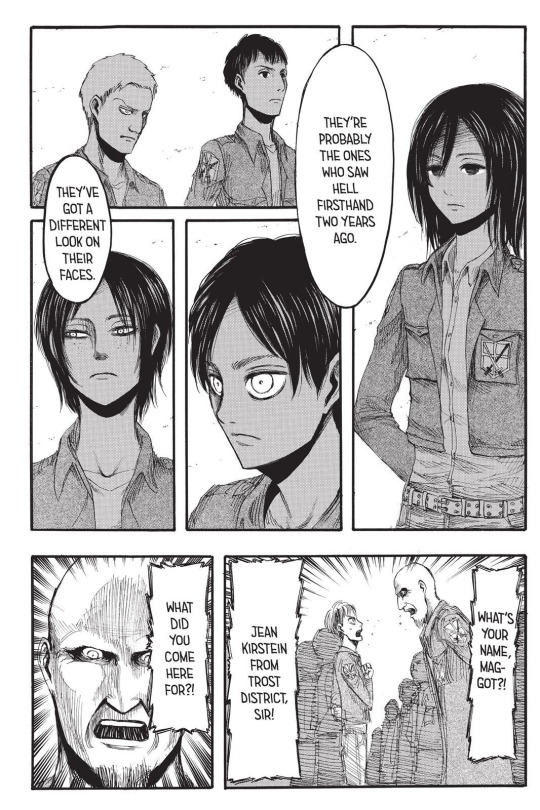

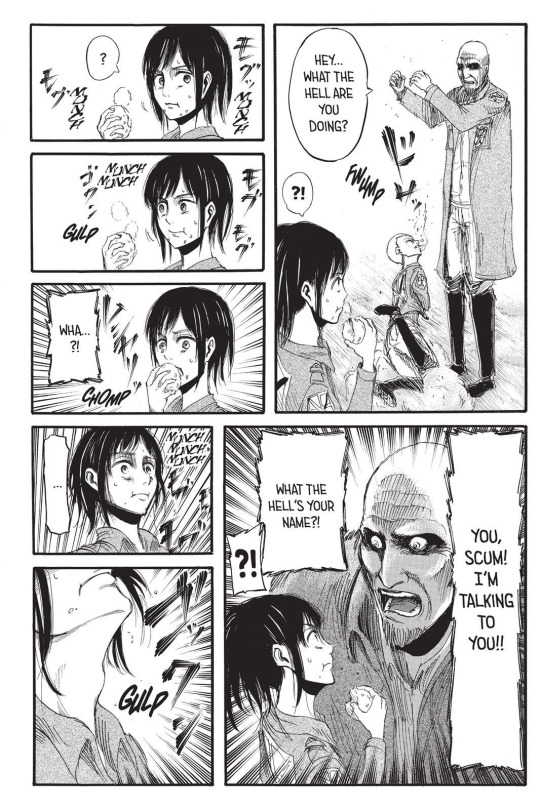

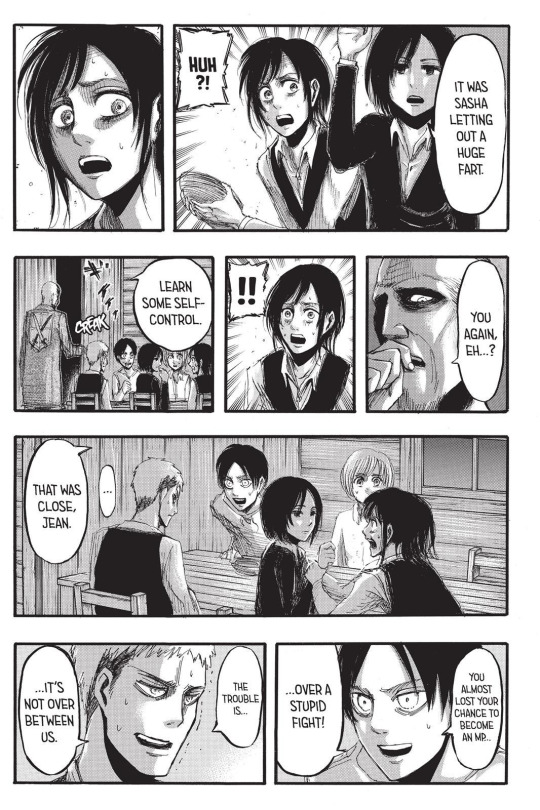

The Training Corps Arc: Cruelty to Children

Yes, this one belongs here. I know that it technically occurs post-Trost in the manga, but it’s the only flashback arc in the entire story, and I think we’d all agree that pacing-wise it’s... not well placed post-Trost. The anime did a good by moving it to immediately follow the intro arc.

Basically, the main theme here is that innocent kids lose innocence. From the humorous to the cruel, we see it. The kids shouldn’t be joining the military; it’s awful that they are.

It introduces Sasha:

And makes sure to show us them just being kids:

Additionally, it shows us the determination Eren has to work hard and be the one to destroy the titans:

Eren’s determination leads to his success in his training, but as we’ll later see, his obsession is destroying him.

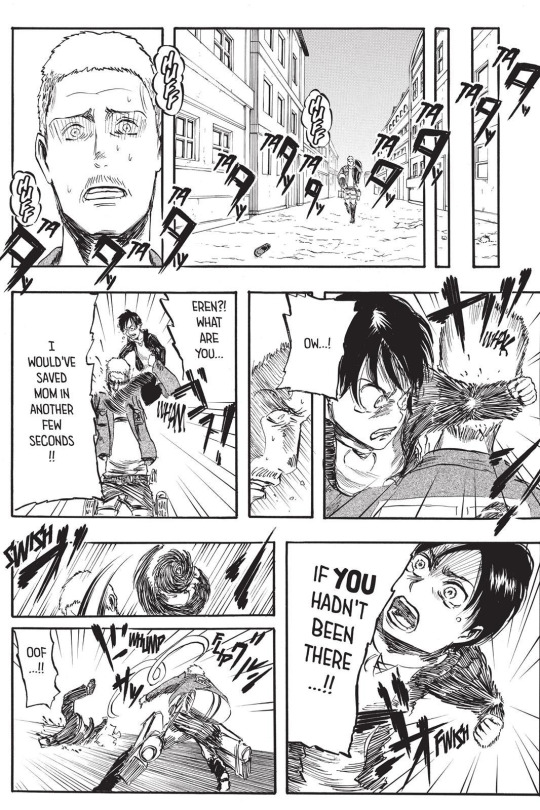

Trost Arc: Cruel Loss, Beautiful Hope

Or, the arc that contains one of my favorite moments, but also almost led to me stopping watching SnK when I first got into it.

The arc begins with our first rematch: humanity vs. the titans, round two. (Thus, it parallels the Fall of Shiganshina).

So let’s discuss that favorite moment of mine: when the 104th teams up to defeat the titans. Even Annie, who is later revealed to be an enemy, saves Connie.

Trost, of course, contains the first big “WTF” plot twist of the story: when Eren is “reborn” out of the belly of a titan. When a character is in an enclosed space in literature, especially one with liquid, viscera, and blood, it’s probably a symbolic rebirthing scene. From, at that point, Eren’s lowest moment of defeat, Eren realizes he has the powers to change things.

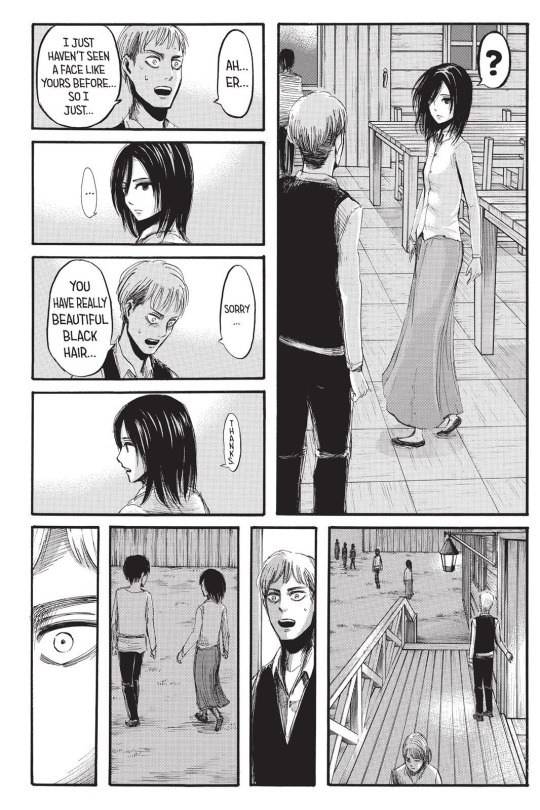

But Eren is not the only one who comes to an important realization this arc. Like the Fall of Shiganshina, Return to Shiganshina, and the final arc, there is EMA focus. Mikasa makes a decision to live on despite loss:

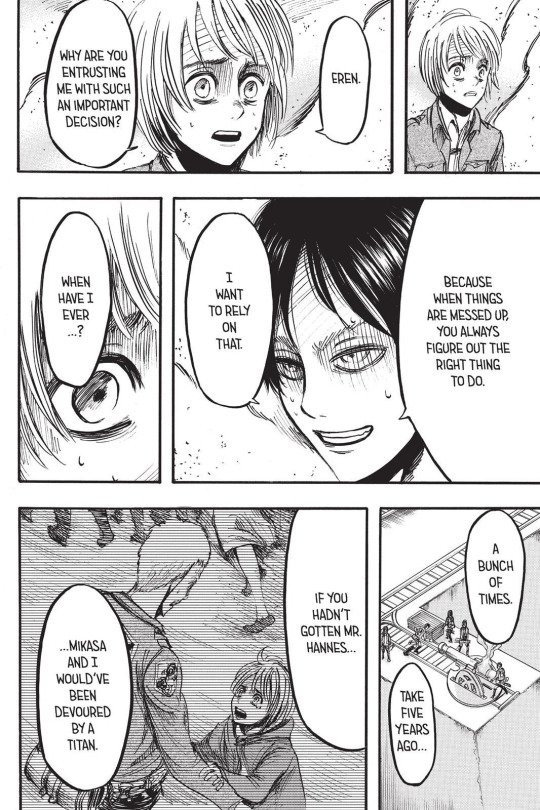

And Armin receives affirmation of his self-worth and realizes that even if fighting isn’t his skill, strategizing is just as valuable:

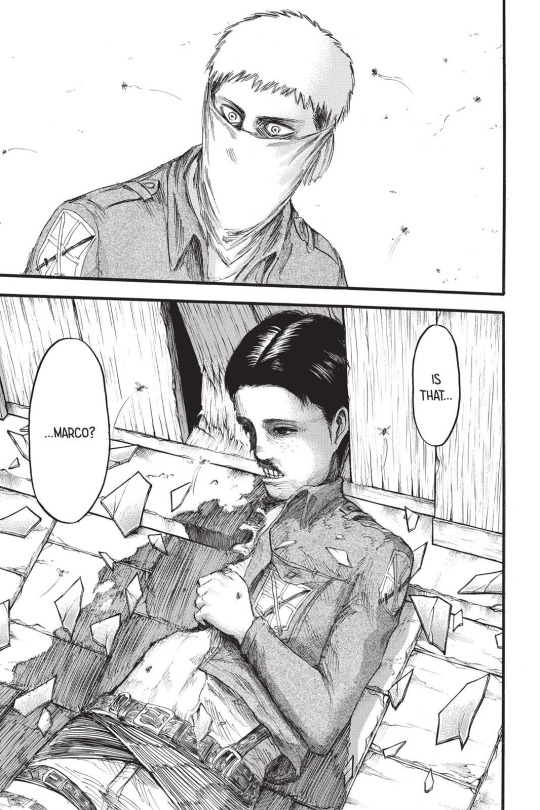

This arc also contains Marco’s death, marking the first time the 104th have to cope with the loss of one of their own.

The arc’s final fight is concluded with Levi Heichou shows up to save the day.

And, of course, the concept of blocking the hole in the wall is first brought up (this time with a boulder), and the military needs to make a choice about whether to use Eren or exterminate him; Armin is able to convince them to trust Eren.

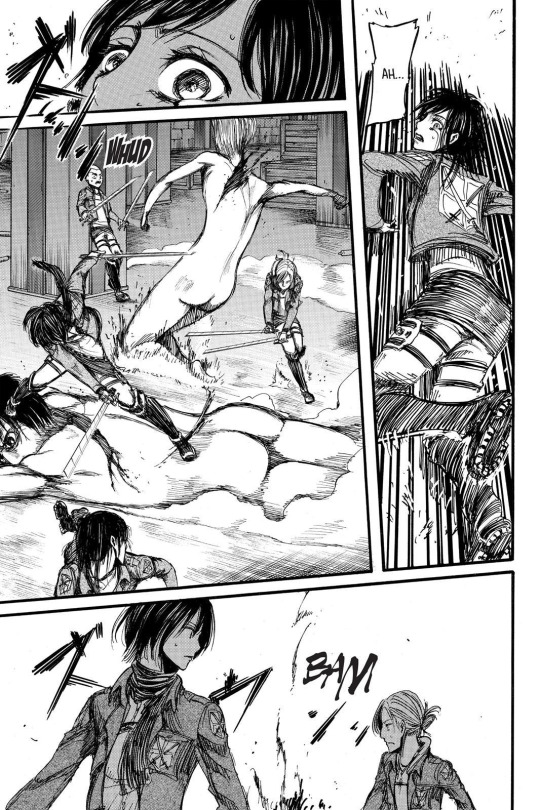

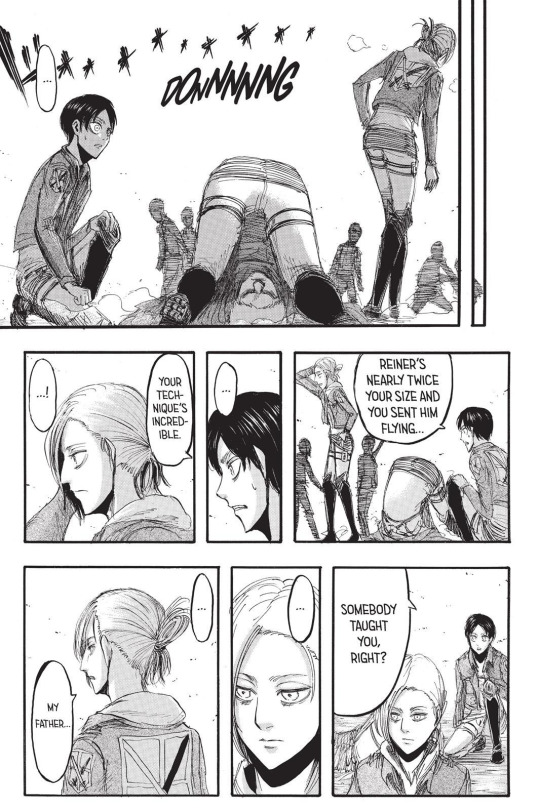

The Female Titan Arc: A Cruel End to a Friendship

The arc contains a notable moment of Eren deciding to trust his colleagues--Levi’s squad--only to lose them all.

Additionally, Eren’s relationship with Annie ends poorly (obviously. Should Annie be in the paths right now, as she likely is, I don’t think she’ll respond well to Eren either and is more likely to help take him down). Like Eren taught Mikasa to fight and to live, Annie taught Eren how to fight as her father taught her.

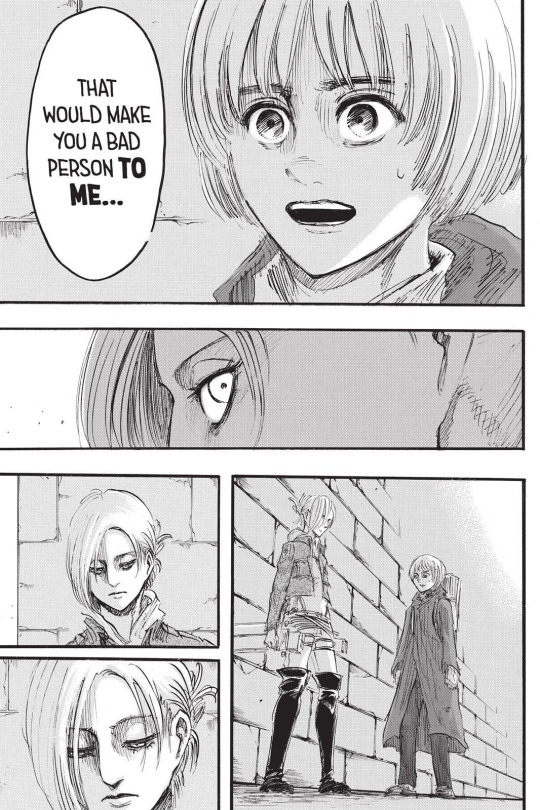

What’s notable about this is that Annie’s relationship with her father is cruel and beautiful--he clearly wanted nothing more than for Annie to survive and he’s still waiting for her. Annie embodies this dichotomy as well: Armin notes that she is exceptionally kind, yet the world doesn’t give her a choice. She is so kind that she spares Armin and goes along with his plan to capture her despite knowing it is a trap, because she does not want to hurt friends, because she wants to be a good person. Annie wears a cold mask, but she is truly kind.

The Female Titan Arc concludes when Eren accepts the monstrous part of himself, using everything he has to fight Annie. It’s not a coincidence that the arc ends with Annie ripping off part of the wall, revealing the titans within. This symbolizes that the structures that ostensibly were erected to protect society are built around the monstrous, and thus sets up the Uprising Arc.

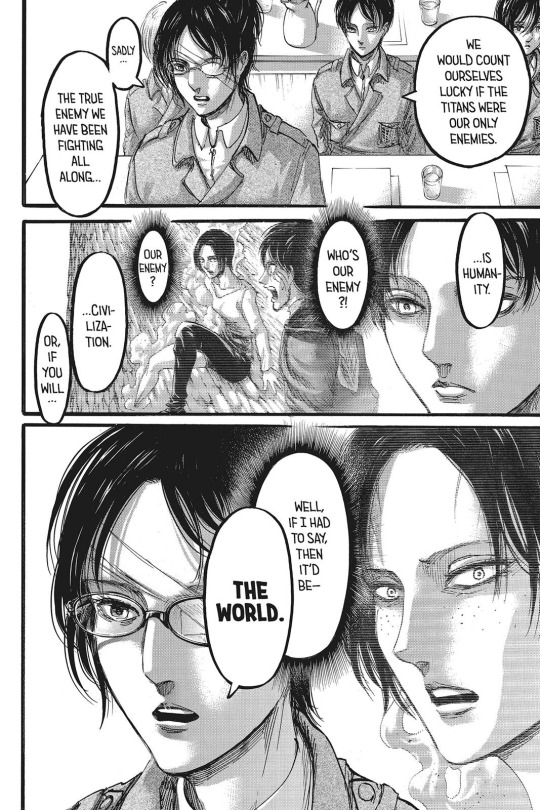

Clash of the Titans Arc: The World is Cruel and Also Beautiful

My favorite arc.

It contains several important elements: it’s where Ymir hints at the true enemy of the story, and it’s where we start to see that the Survey Corps might be capable of cruelty as well.

Erwin sacrifices his arm, foreshadowing his later sacrifice of his life, Ymir and Historia assure each other of their love (almost like love, connection, and humanity are braided themes)...

It’s also where Eren is revealed as the Coordinate, and where the central relationship of the story as @linkspooky writes (and theorizes) about here develops in a moment that is truly beautiful and cruel. Mikasa declares her love for Eren, but Eren pulls away because he needs to fight titans to keep living.

It also foreshadows and acts as an inverse to Eren’s tragic current choice: he chose to fight instead of to accept love, but he had little choice then and was acting heroically. He had choices now.

Additionally of note, since this arc is the central chiasm of the story, it contains elements from both the A and B parallels. Such as, for example, Sasha receiving development and the focus on the suffering of children, from Sasha saving Kaya (beauty) to Nanaba and the others dying to protect the 104th:

Also, the Hannes storyline reaches its conclusion with Hannes’ death, proving for once and for all that Hannes is no coward:

The death of Hannes is symbolic of the EMA trio moving from a child stage to an adolescent stage in their metaphorical development. It parallels Carla’s death, and Levi’s (the final mentor figure for EMA) current near-death experience (I don’t think Levi needs to die nor do I think he will at this point, because he seems to have survived the parallel incident).

The Uprising Arc: A Beautiful Beginning to a Friendship

There are quite a few parallels here with the Female Titan Arc. We have two parallels with Annie’s complex relationship with her father: Historia and Levi (with Kenny for Levi). Like with Annie’s father, Kenny is not a great father figure, but he did want Levi to survive and gives him a life-saving tool right before he dies (the titan serum). Historia has the direct opposite relationship with her father as Annie: Annie’s father loves her but treats her harshly to teach her to protect herself; Historia’s father appears to treat her kindly, claiming he’s always wanted a relationship with her, but he actually does not care about her at all.

Historia and Eren’s relationship also foils Annie and Eren’s: if Annie and Eren’s relationship leads to Eren accepting the monstrous/titan part of himself, Historia and Eren’s relationship leads to Eren accepting the weak, unspecial part of himself.

Additionally, this arc focuses on the new Squad Levi, replacing Petra, Oruo, and the others--and this time, Squad Levi really does come in clutch, saving Eren and Historia. These scenes are deliberately paralleled--as in, there is a literal flashback in the Uprising Arc to Eren having to make a decision re: Squad Levi. When Eren acts on his own instincts this time, he saves them.

Return to Shiganshina: Cruel Loss, Beautiful Hope

Like the Trost Arc, it contains a rematch between humanity and their enemies; this time, however, it is not mindless titans who are the real enemies, but Bertolt and Reiner (and Zeke), demonstrating how personal this fight has been (going from a journey of strange monsters-->friends-->your own internal heart in the current arc). It also, on a more basic level, contains the goal of plugging up a hole in the wall, this time with Eren’s hardened shell.

It also contains the 104th teaming up to take down an enemy. Only, this time, instead of Annie and Mikasa dealing the killing blows to titans about to kill Sasha and Connie, they are teaming up to kill Reiner, a former friend.

Like in Trost, when Eren was “reborn” out of the belly of a titan, Eren experiences a moment of awakening here. He realizes he is not the hero of this story: Armin is.

And likewise, Mikasa makes a decision to accept loss and live on.

And Armin receives affirmation of his self-worth and his strategizing doesn’t just save Eren this time, but potentially humanity:

This arc also contains the flashback to Marco’s death and, of course, Bertolt’s death, which heavily, heavily parallels Marco’s. Like with Marco, Bertolt’s once-friends are watching and weeping, but they choose not to help him for the sake of their mission (again: you become the monster; this is however NOT a commentary on the morality of such decisions, but instead is an observation. Bertolt’s death, even if you choose not to blame the Survey Corps, is horrific and agonizing and cruel).

And of course, guess who saves the day and determines the future of the story? Levi Heichou. However, again, in keeping with the motif of conflicts getting more personal, Levi does not have to kill a monster titan (in fact, he fails to kill Zeke, though he does take him down). Instead, he has to choose to let his best friend die. Like in Trost, where the military needed to make a choice about whether to listen to Eren, Levi chooses to save Armin (though not because of Eren’s please necessarily, but because of his own care for Erwin).

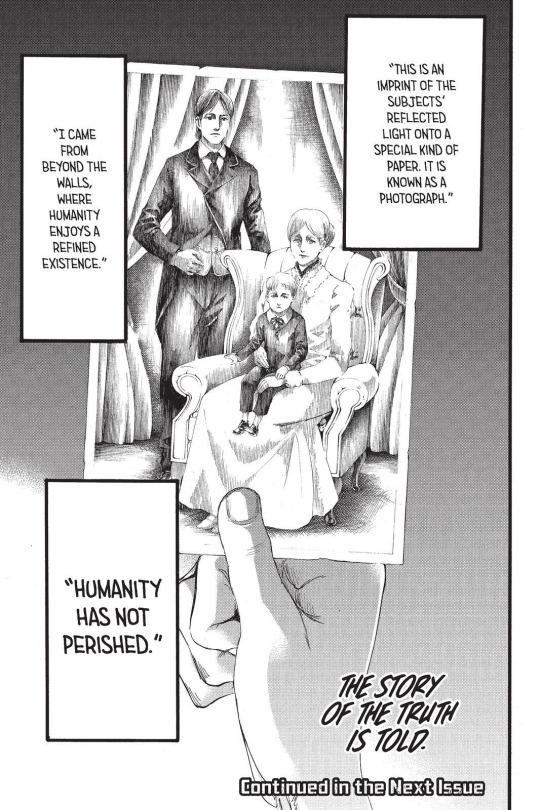

The battle of Shiganshina, like how the Battle of Trost ends with Eren emerging as humanity’s hope, ends with a revelation to change the story forever. Humanity is not extinct.

The Marlay Arc:: Cruelty to Children 2.0

Innocent kids lose innocent in both the past and present in this arc. The arc sets up copious Reiner and Eren parallels, showing how they both worked hard in training to become heroes.

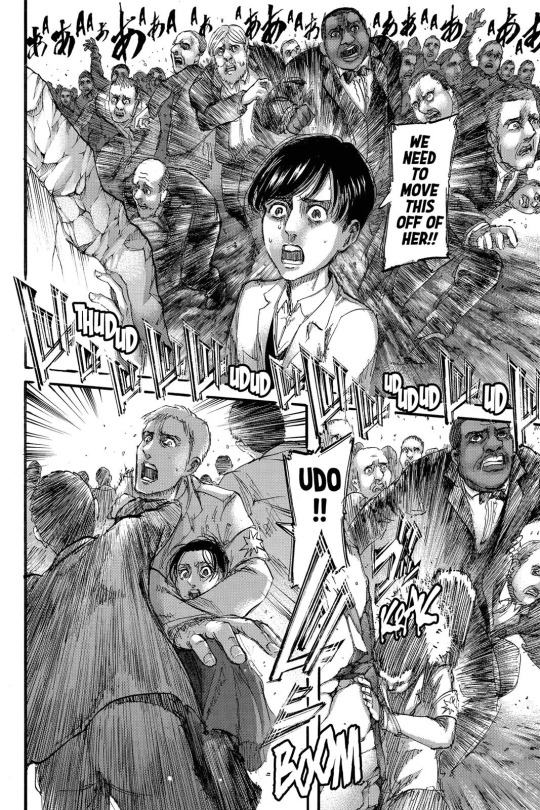

Additionally, we see that being perpetuated to the next generation in Gabi and Falco, Zophia and Udo. They are just children, but they are killed horrifically and fight in wars as part of their training (it’s even worse than the Paradis military):

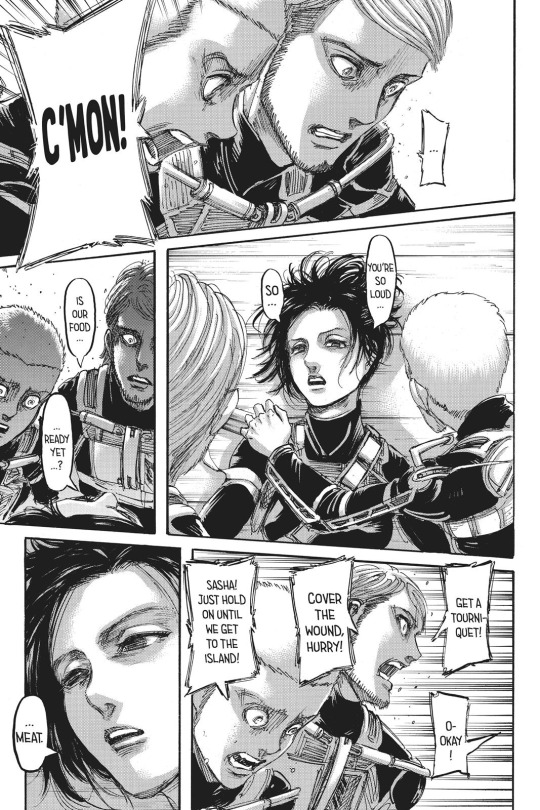

Like all other B parallel arcs, it also contains focus for Sasha. She chooses not to kill a child, providing a beautiful counter from the cruelty of Eren’s actions. Yet, she pays the price for this beauty, as she is cruelly murdered. Sasha may not be a child herself anymore, but she is still a person, and the focus on food for her in the moment of her death reinforces this.

We also see that our grown-up children are losing innocence as well. Eren becomes the monster he swore to destroy, becoming a titan to murder innocents.

Final Arc: The World is Beautiful (and cruel)

I know the emphasis right now is on cruelty and I don’t mean to minimize it. From Historia to how Eren treats his friends, to what Eren’s currently now doing, it’s painful.

It contains a return to Shiganshina, like the Fall of and Return to Shiganshina arcs. And like the first arc, it irrevocably changes the world. On this day, humanity has received not a grim reminder, not a choice.

Instead of Mikasa and Armin receiving help from an adult to save Eren (Hannes), they are the adults this time. It is up to them to save Eren from himself, which likely is not going to be kind enough to spare Eren’s life this time. That said, I do think/expect a moment of Eren remembering his humanity in the end. And we already know it ends with life and freedom.

#snk meta#chiastic structure#aot meta#shingeki no kyojin meta#attack on titan meta#snk 123#eren jaeger#mikasa ackerman#armin arlert#ema#levi ackerman#yumihisu#historia reiss#annie leonhart#sasha blouse#reiner braun#marco bodt#bertolt hoover

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

41, 22, 14, 12 and 9 for Cheslock, Violet and Edward. Thanks

9. MAKEUP?

Cheslock

He doesn’t really remember when he started wearing makeup. Really, he felt that lip stuff was way too gaudy for him - it suits Violet quite well, but it really isn’t his scene. He also wears makeup over the scar under his left eye, dramatising it into his iconic look so it’s less visible.

Violet

Rather than being told to grow out of it, Violet was left to his own devices when his mother simply accepted that the makeup covered up how tired her son looked. At least she was there to steer him away from whatever poisonous materials he thought would be alright to apply to his eyes… but he still continues experimenting nonetheless.

Edward

There is no way in the seven hells that you’d ever catch him wearing makeup of his own will. He has to be forced to sit down by either Elizabeth, who wants to test something, or Cheslock, who probably forced him into it with a bet. There is… a certain fear when applying coal dust and vaseline to one’s eyes for mascara. During his Phantom Five concerts, the sultry half-lidded look that he gives fans is only the look of “I have something stuck in my eye, please help me.”

12. FAVORITE BOOK GENRE?

Cheslock

He reads a lot more than one would think. Cheslock’s a big fan of the gothic genre, with copies of Carmilla, Frankenstein and Jekyll and Hyde up on his shelf. He doesn’t really get much time to read, but when he does, he rereads all of this stuff.

Violet

He still remains a lover of the epics. Not just the English traditional Paradise Lost or The Fairie Queene. Violet actually enjoyed studying the Odyssey and the Iliad, even if they were school set texts. There’s just something so interesting in exploring a distant past that actually has him reading stories that others would find tedious.

Edward

He doesn’t read. Well, at least, he doesn’t read as often as he wants to. However, his favourite genre would probably be the ‘social-purpose’ novels. The ones that bring to light the injustices of society. Edward reads them because he knows his disposition as an affluent man and wants to learn more about others.

14. PHYSICAL ABNORMALITIES? (BOTH VISIBLE AND NOT, INCLUDING INJURIES/DISABILITIES, LONG-TERM ILLNESSES, FOOD-INTOLERANCES, ETC.)

Cheslock

The scar that runs over his left eye was something from childhood, a particularly bad scuffle with his father. The two don’t exactly have the best of relationships.

Violet

The white forelock in Gregory’s hair is natural. As a child, his parents were worried that this, coupled with his ‘quiet temperament’, was a sign of him being afflicted with some sort of genetic defect. Growing up, it was later realised it wasn’t anything detrimental to his actual health.

Edward

Edward has already been written for HERE

22. GIVEN A BLANK PIECE OF PAPER, A PENCIL, AND NOTHING TO DO, WHAT WOULD HAPPEN?

Cheslock

He wants to make something good. Cheslock isn’t the best of artists, but he still knows what’s good and what’s bad. He gives up half way on drawing people and ends up drawing dicks all over the page.

Violet

Of course he’s going to draw something really elaborate. Violet isn’t one to draw whatever’s in the room, but something straight from his imagination. He could draw up amazing scenery or detailed flora from memory without a problem - and remembering is a skill in itself - but that’s only if he has the drive to actually do it.

Edward

Edward is a horrendous artist. That doesn’t stop him from trying to draw something. He tries to draw portraits of whoever is around, but… his work could probably be considered insulting.

41. HOW MISANTHROPIC ARE THEY?

Cheslock

He doesn’t detest society, but he does have some grievances with how class seems to define people. Cheslock just does whatever he wants, without mind of people. It’s not exactly something extreme. He just minds his own business.

Violet

It isn’t as if he hates people, but… he’d just rather avoid them. Violet loathes wild parties and gossip, knowing just how out of hand one can get when inebriated. The only people he willingly hands around with are kids, because he finds them pretty easy to entertain.

Edward

There is no way that Edward could say that he hates people. Sure, he does have some problems with how unequal society is, but he doesn’t see humanity as inherently evil. People have just “lost their way”, as he says.

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

Slightly random question: any thoughts on redemption in the Atreides? Basically everyone (besides Iphigenia?) does something at least somewhat morally reprehensible and has to deal with consequences, but I think this is the first story I've read where no one gets magical redemption? Even Orestes' acquittal is more of a "you did bad but your mom did worse" judgment. Fiction has a habit of trying to redeem bad-ish characters through death or shrugging. Any thoughts on how the Atreides fare? Thanks

Hey! Sorry my answer is a little late…I’ve been thinking about this one a lot! Can’t say my answer is at all the right one, since it kind of involves looking at cultural tendencies and that isn’t my specialty, but here’s at least some of my thoughts:IMO, you don’t really see redemption plots in general in greek mythology (though if anyone knows some good examples please leave a comment! I’m interested to hear.). A possible reason for this is that redemption typically entails a ‘bad’ character becoming a ‘good’ character. The way we as a modern audience categorize characters– hero, villain, etc– doesn’t apply the same way to ancient fiction. A hero in greek mythology is someone who is still allowed to have considerable moral gray area, as the classification is based more on their physical traits than their personality. So in general, this makes me wonder if an ancient audience just wouldn’t see the need for their characters to be ‘redeemed’ if they weren’t examining them through the same moral lens as we are. Take a character like Odysseus… he does tons of horrible things during the war, but doesn’t need go through any redemption arc to get his eventual good ending (I mean, he has to face several trials in the Odyssey, but that’s not really a transformation of his core character which I associate with redemption.)

Getting back to Atreides specifically… I think modern audiences are more inclined to look at Agamemnon as a ‘bad’ or even villainous character than an ancient one would have been. You have to remember he already has a sort of plot arc of learning his lesson within the Iliad itself, going from the man who makes a great mistake in book 1 which leads to a lot of unnecessary deaths, but then later is also given scenes like his aristeia, which is by definition is something shown in a heroic light, and he makes amends with Achilles by the end of the Iliad. If you look at the Iliad by itself, you could even say call that a sort of mini redemption arc I suppose since it does involve some character development from ‘bad’ to ‘good’ (initial bad impression, doubles down on the bad decisions, but eventually admits he was wrong, changes his actions, proves himself a better commander, etc). On a broader scale, also remember that Agamemnon was considered a hero by ancient standards to the point he had a cultic epithet associated with Zeus. So all in all, a redemption arc I don’t think would be seen as necessary for them to still take away good from his character.I suppose you could say Menelaus’ character gets the closest to what we might consider redemption, going from the warlord of the Iliad to the helpful father figure of the Odyssey, but again that isn’t really so much that anything transformative happened to his character as that the context we’re seeing him in changes.Another thought: does a character like Orestes’ actually qualify for something like redemption (ie: is he ever a ‘bad’-ish character to begin with)? Maybe if he had murdered his mother by his own decision, but we see from the beginning that he is considerably reluctant to go through with it, yet is compelled both through the unquestionable order of Apollo as well as his sister Electra. I’m not really sure what the ultimate ancient opinion would have been on him; some characters are shown talking about him negatively, but then for example, Nestor in the Odyssey, while speaking with Telemachus, calls Orestes a good example of courage and strength. and I feel like Orestes himself is typically shown in a sympathetic light? On a broader scale, the house of Atreus is known for being Inescapably Cursed and is typically used as an example for What Not To Do, so of course they’re going to be dealt a worse hand and not be given ‘satisfying’ endings. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯I guess in the end my final take is that a modern audience wants a redemption arc because we are left feeling that the character’s potential for better was wasted. But if an ancient audience didn’t consider the same things to be flaws that we did, this would be a moot point to them. Anyway, these are just some thoughts and guesses of mine. I’d love to hear other people’s input too!

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trip to Greece (2020) - Review

The Trip films are an odd bunch. Director Michael Winterbottom has been filming the travels of Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan while they play caricatures of themselves for ten years now over the last four films. In fact, the films aren’t even the original product of their work. Winterbottom first edits and releases the footage as a television series for the BBC that is usually about double the final length of the eventual feature film. I’m not sure if there’s any way for a Yankee like myself to lay my eyes on the full, 3-hour television versions, but I’m also unsure whether the extra footage would add or detract from my enjoyment of the film. Largely, it would depend on whether that extra footage was more of the The Trip’s comedy portions or drama portions. Generally, the former far outstrips the latter.

This is all to say, I find this series the most enjoyable when it doesn’t try to be too overly ambitious in trying to be dramatic art. Most people are like myself: they are turning on this movie because they want to see two very skilled comedians riff on one another. In particular they want to see them show off their incredible skills for impersonation. The Trip to Greece has no clear stand-out scenes of impersonations like the previous films. The first film will be immortal for the two comedians’ dueling Michael Caine impressions, and in some ways each of the subsequent films has always seen the pair struggling to recreate the freshness and originality of the first film’s easy back-and-forth energy. The second movie expanded on the viral nature of the first film by revisiting Michael Caine with the added joy of ripping on Tom Hardy’s non-understandable Bane. Plus, that film saw pitch-perfect, darkly comedic performance of Brydon’s famous “man-in-a-box” voice at the ruins of Pomepii, making it seem like there was someone still trapped inside the site’s molten figures. Then, for me, while the third film is the weakest of the bunch, Coogan’s Bowie and Brydon’s Jagger impressions single handedly made it worthwhile. This film’s coup de grace comes in a superb scene where the pair recreates the dentistry torture scene from the Dustin Hoffman & Lawrence Olivier movie Marathon Man. There’s also an impressive feat of ventriloquism where Coogan speaks while also making his mouth look like they are saying different words, as if someone is dubbing a voice over him.

Luckily, these movies don’t rely exclusively on only scenes of impersonation. The conversation between the two talented actors is entertaining on its own, with one always racing to beat the other to punch line. The winner is always us, the audience, and that remains true in this film.

But as I mentioned, the comedy is only about half the equation for each of the film. All of them have a sadness that runs just below their surface. Generally, it revolves around a failed or, in some cases failing, marriage of one of the actors. Or perhaps the two actors start to discuss and struggle with the fact that they are aging and feel that their lives lack meaning. A not-so-subtle loneliness lives at the fringes of the films, particularly when it focuses on Coogan’s character. At its best, the dramatic aspects of the films are thought-provoking and act as sobering subtle criticisms of the seemingly hedonistic, vain lives of actors and those in show business. At its worst, like in The Trip to Italy or The Trip to Spain it’s a self-indulgent mess that we put up with just so we can get more of the impersonations and snarky banter. The first film probably balanced the drama the best by leaning harder into the comedy throughout, with the dramatic undertones only becoming prevalent at the end – a beautifully impactful end to an otherwise frivolous film.

This movie leans much more into the drama than the first film, but unlike the prior two installments the drama is still well-balanced by the comedy. I think that this is largely due to the fact that the actors decide to slide back into their respective roles from the first film. This means that Coogan plays the role of the self-important, womanizing, superior actor, while Brydon is the more light-hearted, good-natured, merry-prankster, unlike in The Trip to Italy where their personalities seemed reversed. And, importantly, this film gives equal screen time to both actors instead of The Trip to Spain where the dramatic bits were skewed towards Coogan.

But above all else, I think the film feels so balanced because it takes such great advantage of its setting to enhance the drama rather than just serve as a pretty backdrop for silly conversations. The script uses the Grecian landscapes to hearken back to the ancient Greeks, with particular emphasis on this land being the birthplace of drama and comedy. Unlike today where “dramedies” dominate much of the premium TV landscape, for the Greeks these were two completely separate styles of theater. Dramas were largely devoid of comedy, and vice versa. The Trip to Greece take advantage of this separation and allows each of its character to embody a different stereotype. The self-important Coogan, of course, embodies the drama. He scoffs at Brydon’s lack of knowledge of Classical philosophy and seems more impatient than ever with Brydon’s imitations. He particularly bristles when Brydon claims that Coogan’s recent BAFTA-winning dramatic performance as a real-life comedian/entertainer in Stan & Ollie was nothing more than an imitation. Brydon, the light entertainer, is like a court jester, always smiling, the embodiment of comedy.

But what I like even more than how this comedy/tragedy separate thematically resonates with the actors’ temperments is how the movie uses this same duality and applies it to the overarching “plot,” if it’s appropriate to even call it that. The whole idea behind this particular trip is that Coogan and Brydon are going to follow the course of Odysseus’s eponymous Odyssey. In fact, the first words we hear from the movie, with the screen is still dark, is Brydon reciting the first words of the Iliad. The first image we see is the pair looking over the ruins of ancient Troy. What’s so wonderful is that the actual Odyssey is not a piece of theater. It’s an epic poem with as many pieces of light-hearted adventure and romance as there are set pieces of grief, destruction and other heavy drama. As such, the film allows Coogan and Brydon to experience their own, separate aspects of Odysseus’ original journey. By the end of the film, both do reach their respective homes, but in a way that matches the vibe of type of theater they embody.

Like any good Shakespearean comedy, Brydon’s journey ends with a marriage of sorts. Ever the light-hearted romantic, he asks that his wife fly out to meet him in Greece. Now, far from his home in England, Brydon has found his home in his wife, his Penelope. With the domineering Coogan out of the picture, Brydon becomes king of his castle, i.e. now HE drives the car.

Meanwhile, Coogan is haunted throughout the film by the possibility that his ailing father will die. His eventual death is all but confirmed by a dream Coogan has midway through the film which essentially recreates Aeneas’ famous flight from Troy while carrying his son and aging father. As those who know the Aeneid know, only one of those three will survive to make it to their new home. His dramatic story arc concludes with the emotional reunion all the way back in England between himself and his son, recalling Odysseus’ eventual reunion with his own son Telemachus.

It’s a beautiful way to end the film. It gives consistency and weight to the fairly rigid juxtaposition of to the two character’s personalities in the film, and it does so in a way that almost seems fated in a way that recalls Greek tragedy. This thematic consistency is overall satisfying without being distracting in the way the dramatic portions detracted from the second and third films. Ultimately, it serves to complement the comedy you show up to enjoy. While it will always be tough to top the first film’s originality and surprisingly poignant end, this is by far the most artistic film in the series, and the arguably the best since the series began. Here’s to more and more trips to come!

*** (Three out of four stars)

0 notes

Text

Athena in the Homeric Epics: Rediscovering Her Complexity

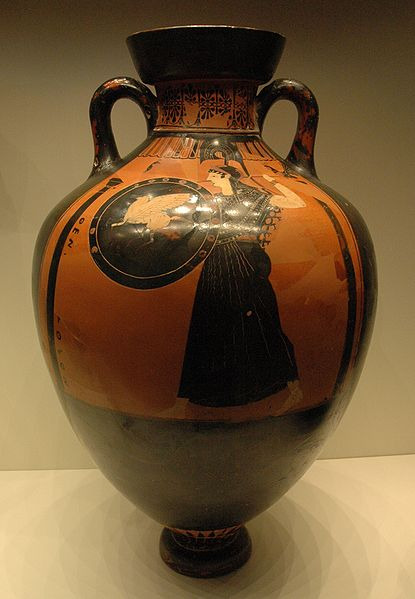

Bas-relief sculpture of the Roman goddess Minerva recovered from the ruins of Herculaneum (Image in the public domain)

For the purpose of this project, I focused on Athena as she is represented in the Homeric epics and related tales. Although Athena’s worship began well before that time and has intriguing possible connections to prehistoric goddess worship, and also continued into the Roman period with multiple synchronisations, I wanted to reexamine the character of the goddess as captured in the older Greek myths. Greek and Roman mythology is commonly taught in schools, including allusions to it as an original source of Western culture, and the Homeric epics in particular are often held up as some of the earliest extant literature. The passing familiarity that results from this kind of exposure can give an impression that Athena is a warrior goddess, or a goddess of wisdom, although most people have trouble remembering exactly the role she played in the Iliad; the myth most commonly associated with Athena is the story of Arachne, which is one of the few where the goddess alone takes centre stage. The story of Arachne emphasises the goddess’ patronage of weaving as a useful household art, but the short vignette hardly captures the dynamic vitality of Athena’s character as she appears throughout the earlier epics. By comprehensively reviewing her appearances in the Homeric epics, this project strives to rediscover the complex nature of Athena in the Archaic period and to understand how that persona of the goddess might be approached in the context of contemporary women’s spirituality.

In the Homeric epics, Athena’s primary role is as a warrior: she is commonly referred to as “heaven’s triumphant maid,” “the martial maid,” or as the “all-conquering.” Her other most frequent epithet is “blue-eyed maid,” which may also be translated as “shining-eyed” or “gleaming-eyed.” In Homer’s tales, references to her mastery or patronage of weaving are only side-lights. In a couple of instances, she appears in human form as “a fair virgin in her beauty’s bloom, / Skill’d in the illustrious labours of the loom,” and it is specifically mentioned that when Hera wanted to impress Zeus with her beauty, she wore a robe woven by Athena, but no specifics of this weaving are mentioned. The vast majority of Athena’s appearances refer to her wearing armour or being in disguise.

Ancient Coins with Images of Athena ( © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons)

Her varied appearances are the first example of Athena’s complexity. She does not conform to simple ideas of gender for either the ancient Greeks or for us. Her role in the Iliad, in fact, is due in part to this masculine attitude: she was one of the three goddesses who claimed the golden Apple of Eris (Discord). Paris, judging between the three, refused Athena’s offered bribe of wisdom and skill in war. Instead, he judged in favour of Aphrodite, accepting from her the love of Helen, the most beautiful mortal woman. Aphrodite approached Paris using the wiles of beauty and the promise of love to win him over; Athena, and Hera, who also lost, approached him almost as an equal, trying to win him over with offers in the masculine realms of rulership and war. Afterwards, Hera and Athena had a solid alliance because of their loss, and Athena often acts on Hera’s behalf.

Interestingly, Athena also acts in Zeus’ name and even uses his symbols: the aegis was originally his, although it appears more often as part of Athena’s equipage; when she takes the form of a bird, it is as an eagle, Zeus’ bird, not an owl; and with his permission, she even wields the thunder and lightning that are Zeus’ identifying characteristics. Thus Athena’s outward signs and symbols are almost universally masculine. In fact, the way she crosses gender boundaries almost seems to deprive her of a gender of her own: she is not described as virgin solely because she had “autonomy and independence.” She is virgin in the literal sense as well; no myth depicts her having a lover, human or immortal, or even to be interested in one.

Her status as transgressing or simply disregarding gender boundaries does grant her unusual freedoms, though, and makes her the ideal intermediary between the goddesses and the gods. Athena’s work on Hera’s errands and her own often involves interacting with Ares or Apollo, or even Zeus. Ares, when fully engaged in his martial bloodlust, seems almost unapproachable, especially by one of the unarmoured goddesses, but Athena faces him without fear. In contrast, although she is approached by other goddesses, Athena is only invoked by a woman in the Homeric epics on behalf of a man. Hecuba, queen of Troy, petitions Athena once, when advised to do so by her warrior son, and pleads for Athena’s mercy on the city, but Athena refuses to hear her. Later, Penelope petitions Athena to watch over Telemachus, the son of Athena’s favourite hero, Odysseus. This petition is successful, but Athena was already helping Telemachus, and did so for Odysseus’ sake, not because of Penelope’s petition. When Penelope bemoans her own situation or asks for help from a goddess, she turns to Artemis, not Athena.

Given these interactions, it is perhaps unsurprising that in her relationship with her devotee, Odysseus, Athena acts more as a comrade or adviser than as a mother. Even in combat and when protecting his life, Athena’s assistance is not described in the way other goddesses’ supervision of their charges is; she is much more likely to take form and engage in combat alongside Odysseus, or to act on his behalf, than to coddle or nurture him. When she does engage in combat, Athena’s approach to fighting is as complex as her gender presentation.

Amphorae with Images of Athena (Left photo: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.) (Center and right photos: Images in the public domain)

In one dramatic scene, she appears on the battlefield to face down her brother Ares, and after he insults her and implies she is merely causing trouble, she picks up a rock and knocks him unconscious with a single blow. In another violent scene, at the end of the Odyssey, she inflames an already tense situation and engineers a complete massacre. But almost immediately thereafter, she overrides Odysseus’ fury and enforces a peace on both sides once her sense of right and wrong has been satisfied. In contrast to Ares’ bloodlust in battle, she seems constantly focused on a purpose; victory in combat is only a means toward an end for Athena.

The greatest single example of her approach to combat is the Trojan horse, the epitome of cleverness and trickery. She inspires the craftsman with its design.After this stratagem succeeds, though, the triumphant Greeks fail to pay her sufficient homage, and in anger she wrecks several ships as they begin their journey home. This episode exemplifies how Athena’s pragmatic approach to combat applies her wisdom in order to satisfy her overriding ideas of justice.

Neither her wisdom nor her justice are at all what many contemporary readers might expect, especially from a goddess. Although she is often called the goddess of wisdom, Athena’s expertise might be better described as cunning. She appreciates trickery and does not shy from it herself, in matters as large as the Trojan horse and as small as appearing in the form of a mortal when addressing those who call on her. Athena disguises herself as a good friend of the person to whom she speaks, both to lead Hector to his death and to answer Penelope’s appeal. Odysseus himself is best known for his cunning and wit, not his abstract knowledge or impartial wisdom, and he frequently relies on Athena’s ability to change his outward appearance. Just as Athena spends most of her time carrying a masculine appearance and doing things that are unexpected of a goddess, she seems to value the same gift for inventiveness in her followers.

Athenian Tetradrachm (Image in the public domain)

Her unique approach to morality is best summed up in a tale that is scattered in fragments throughout the Homeric epics. After Agamemnon, the leader of the Greeks, returned home, he was killed by his wife and the lover she has taken while he was gone. His son, Orestes, avenges his father by killing his mother and her lover. For the terrible act of killing his mother, Orestes is pursued by the Furies who seek vengeance, but he appeals to Athena. She establishes a law court on the Areopagitica to judge his case, and when the court’s vote is tied, she casts the final vote, finding Orestes not guilty. One telling gives her explanation as: “I was not borne by a mother. I, a virgin, sprang from the head of Zeus, my father, and I protect the rights of father and son against those of the mother. And so I shall not take the part of the woman who slew her husband to please her wicked lover.”

The overall image of Athena that emerges is composed of a mass of contradictions: she is a virgin who appears and acts in masculine ways, an extremely powerful warrior who disdains fighting for fighting’s sake, and a patroness of cunning who renders judgement based on her own sense of justice, being willing to face down the Furies and deny them vengeance in the process. She is, most of all, a figure of extreme practicality, willing to use appearances to get what she wants, but cutting through what she regards as irrelevant to pursue her own goals with single-minded focus.

Although the Homeric epics do not depict women calling on Athena for their own purposes, she is a figure to whom many women can appeal today, faced as they are with shifting gender boundaries and conflicting messages about appearance and behaviour. A woman could call on Athena when she needs to borrow the goddess’ talent for disguise, when she has to cross boundaries and pursue her own goals, and most of all when she is unwilling to be bound by external strictures or expectations about her behaviour as a woman.

The following ritual is designed to attract Athena’s attention for those purposes. The text is assembled out of adaptations of Pope’s verse translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey. It uses bread, wine, and olive oil, staples of Greek life. Wine is specified here because it was the normal drink of the day; if you need to substitute grape juice, that is appropriate too. Olive oil is sacred to Athena because she gave the gift of the olive tree in order to win a competition and become the patron of the city of Athens, which then named itself after her.Athena’s practicality carried the day again: in the Greek period, olive oil was a food and condiment, the primary substance for cleansing one’s skin, and more.

Ritual to Petition Athena

Cast a circle as usual; call the four quarters by inhaling the scents of bread, wine, and oil, then raising the offering of oil to the south (for the sun’s fire that ripened the olives), wine to the west, and bread to the north.

Do a self-blessing, using the olive oil to anoint yourself. Recite:

I sing Athena’s praise and know, you power above, With ease can save each object of your love; Wide as your will extends your boundless grace; Not lost in time nor circumscribed by place. The salted cakes upon the plate are laid, And thus I here invoke Athena’s aid: Daughter divine of Zeus, whose arm can wield The avenging bolt, and shake the dreadful shield I raise to you the bowl with rich red wine Petitioning you to hear this plea of mine. Your gift, the olive, here poured forth as oil In my libation, asks your aid in toil. Athena, ever on your charge attend, And with your golden lamp my need befriend. If you, the ever-wise, put forth your power, Then prudence saves me in the needful hour. The more shall Pallas aid my just desires, And guard the wisdom which herself inspires.

Dip the bread in the olive oil, then eat most of it, and drink most of the wine, leaving a small portion of each to give as an offering.

Turn to each direction, offering your thanks, then open the circle as you usually do. Take your offerings outside to give them back to the goddess.

It is worth noting that the story of Arachne is itself a late addition to the myths of Minerva, the Roman counterpart of Athena; it is first told in Ovid’s Metaphorphoses, and thus provides little insight into the goddess Athena as conceived of by the Greeks in either the Archaic or Classical periods.