#birgit nilsson (musical artist)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

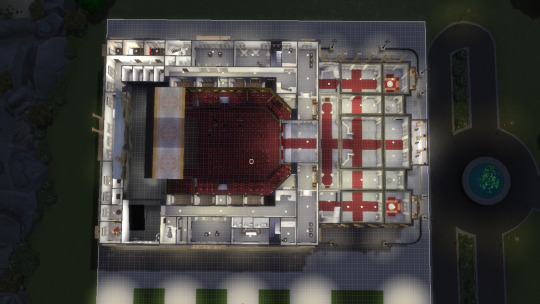

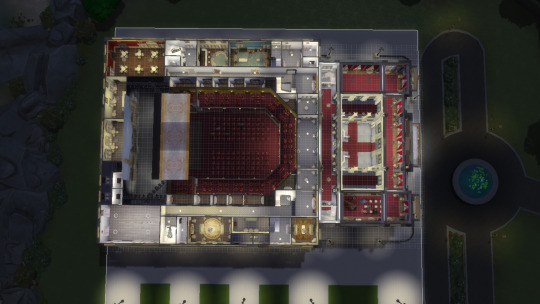

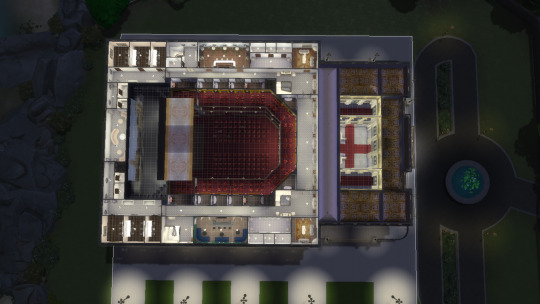

Colon Theatre

The Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires is one of the most important opera houses in the world. Its rich and prestigious history, as well as its exceptional acoustic and architectural conditions, place it on par with theaters such as La Scala in Milan, the Paris Opera, the Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden in London, and the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In its first location, the Teatro Colón operated from 1857 to 1888 when it was closed for the construction of a new venue. The new theater was inaugurated on May 25, 1908, with a performance of Aida. Initially, the Colón hired foreign companies for its seasons, but starting in 1925, it had its own resident companies - Orchestra, Ballet, and Choir - as well as production workshops. This allowed the theater, by the 1930s, to organize its own seasons funded by the city's budget. Since then, the Teatro Colón has been defined as a seasonal theater or "stagione," capable of fully producing an entire production thanks to the professionalism of its specialized technical staff.

Throughout its history, no significant artist of the 20th century has failed to set foot on its stage. It is enough to mention singers such as Enrico Caruso, Claudia Muzio, Maria Callas, Régine Crespin, Birgit Nilsson, Plácido Domingo, Luciano Pavarotti, and dancers like Vaslav Nijinsky, Margot Fonteyn, Maia Plisetskaya, Rudolf Nureyev, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. Esteemed conductors such as Arturo Toscanini, Herbert von Karajan, Héctor Panizza, and Ferdinand Leitner, among many others, have also graced the theater. It is also common for composers, following the tradition initiated by Richard Strauss, Camille Saint-Saëns, Pietro Mascagni, and Ottorino Respighi, to come to the Teatro Colón to conduct or supervise the premieres of their own works.

Several top-notch maestros have worked consistently here, achieving high artistic goals. They include Erich Kleiber, Fritz Busch, stage directors like Margarita Wallmann or Ernst Poettgen, dance masters like Bronislava Nijinska or Tamara Grigorieva, and choral directors like Romano Gandolfi or Tullio Boni. Not to mention the numerous instrumental soloists, symphony orchestras, and chamber ensembles that have offered unforgettable performances on this stage throughout over a hundred years of sustained activity.

Finally, since 2010, the Teatro Colón has been showcased in a restored building, resplendent in all its original splendor, providing a distinguished setting for its presentations. For all these reasons, the Teatro Colón is a source of pride for Argentine culture and a center of reference for opera, dance, and classical music worldwide.

__________________________________________________________

You will need a 64x64 lot and the usual CC from TheJim, Felixandre, Harrie, Sverinka, SYB, Aggressivekittty, and other marvelous creators!

DOWNLOAD TRAY: https://www.patreon.com/user?u=75230453

(free to play 7/17)

#sims 4 architecture#sims 4 build#sims4palace#sims 4 screenshots#sims4#sims4play#sims 4 historical#sims4building#sims 4 royalty#sims4frencharchitecture

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 wunderschöne Trommel Stehlampe im Schlafzimmer

20 wunderschöne Trommel Stehlampe im Schlafzimmer

Sind Sie müde von den Leuchten, die Sie in Ihrem Schlafzimmer haben? Heute würden wir ein paar Schlafzimmerdesigns mit den besten Stehlampen präsentieren, die es auf dem Markt gibt. Sie mögen einfach und uninteressant erscheinen, aber wenn man sie neben den Möbel- und Dekorationswahlen sieht, die sowohl der Besitzer als auch der Dressmaker für diese Schlafzimmer gemacht haben, denke ich, dass du…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

5 Minutes That Will Make You Love Wagner

In the past we’ve chosen the five minutes or so we would play to make our friends fall in love with classical music, piano, opera, cello, Mozart, 21st-century composers, violin, Baroque music, sopranos, Beethoven, flute, string quartets, tenors, Brahms, choral music, percussion, symphonies, Stravinsky, trumpet, Maria Callas, Bach, the organ, mezzo-sopranos and music for dance.

Now we want to convince those curious friends to love the music of Richard Wagner, with very short tastes of his very long operas. We hope you find lots here to discover and enjoy; leave your favorites in the comments.

◆ ◆ ◆ Rian Johnson, filmmaker The problem with isolating a piece from any of Wagner’s operas is insidiously twofold: You’re going to miss (for my money) the real source of its power, and you’re not going to realize you’re missing it because the music is so damn good. Take the prelude from “Das Rheingold.” Put on good headphones, close your eyes, and it’ll transport you, I guarantee.

But it wasn’t meant to live in a vacuum. Wagner is a storyteller, and when the piece sits in its proper place in the pre-curtain dark, birthing you from a pinprick of light into the blinding sun of elemental harmony whose theft will launch an epic, tragic saga of gods and betrayal and love — well, that’s the real stuff.

◆ ◆ ◆ Katharina Wagner, Bayreuth Wagner Festival artistic director I grew up with the music of my great-grandfather, but until today the “Liebestod” is my favorite passage of “Tristan und Isolde.” Isolde expresses her deepest feelings and sings the most beatific passage with great euphoria. Birgit Nilsson, in the recording under Karl Böhm from the 1966 Bayreuth Festival, testifies to the dramatic power and passion of her performance, the size and fullness of her voice, the beauty and purity of her intonation, and her brilliant stage acting. She is rightly considered one of the most important singing personalities of her era.

◆ ◆ ◆ Michael Cooper, Times editor This is the five minutes (well, the scene) that made me fall in love with Wagner. When I first heard it in a college music survey course I was already an opera fan, but I knew little about Wagner other than his antisemitism, his reputation for tedium and bombast, and, of course, Bugs Bunny and “Apocalypse Now.”

This was not what I was expecting: The sheer beauty of the orchestra and the unexpected tenderness of a father’s loving, lullaby-like farewell to his daughter was a revelation. I became obsessed that year, investing in a whole “Ring” cycle (not cheap in the pre-streaming era); buying Ernest Newman’s book “The Wagner Operas” to guide me; and scoring a seat in the second-to-last row of the top tier at the Metropolitan Opera. This was the gateway drug to what became a not-too-unhealthy addiction.

◆ ◆ ◆ Simon Callow, actor, director and ‘Being Wagner’ author The death of Siegfried, the hero in the “Ring” who was to have saved the world, draws out of Wagner an astounding panoply of orchestral sounds of infinite majesty and splendor. It also represents the climax of the system of leitmotifs — melodic and rhythmic fragments associated with particular aspects of characters and their emotional history. Wagner weaves them into the texture with cumulative power so that it is as if Siegfried’s entire past passes before our ears — his energy, his idealism, his passion, so that one feels that an entire life is being commemorated. At the same time, we mourn what might have been. The sense that we shall not look on his like again is deeply affecting.

◆ ◆ ◆David Allen, Times writer You might think of Richard Wagner as the composer of gods and myths, of the end of the world and a love that destroys — and you would be right. But if his sheer ambition makes him someone to be repulsed by and swept away with, in not quite equal measure, he was capable, too, of tenderness of the most affecting kind. His “Siegfried Idyll,” initially a private birthday gift to his second wife, Cosima, was first performed by a small ensemble at their home on Christmas morning in 1870; in the later, expanded orchestration we hear more often now, its ending is a touching depiction of blissful contentment — the warmest, most humane music he ever wrote.

◆ ◆ ◆ Alex Ross, New Yorker critic and ‘Wagnerism’ author Wagner’s “Ring” is, simply put, a study in the futility of power, with the god Wotan as its chief exhibit. The crux of his fall comes at the beginning of his epic monologue in Act II of “Die Walküre,” after his wife, Fricka, has demolished his delusions. He cries, “O heilige Schmach!”: “O righteous shame! O shameful sorrow! … Infinite rage! Eternal grief!” Wagner’s orchestra delivers the sound of power grinding itself to pieces, with monstrous dissonances piling up over a drone of C. In Joseph Keilberth’s great 1955 “Ring” from Bayreuth, Hans Hotter is a howling pillar, magnificent in collapse.

◆ ◆ ◆ Patti Smith, performer I have chosen Waltraud Meier’s exquisite performance of the “Liebestod” from “Tristan und Isolde.” I was privileged to attend the premiere of the opera in December 2007 at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. Conducted by Daniel Barenboim and directed by Patrice Chéreau, it was the most beautiful and moving production of Wagner’s great romance I have experienced.Waltraud Meier is a fine actress as well as being one of our great singers. In this piece, she projects the full range of Isolde’s devotion, desire, madness and loss. She brought to her performance humility and expertise, comprehending fully the meaning of transcendent love.Backstage, I saw her in the shadows. She was yet spattered with Tristan’s blood and still contained in her countenance something of Isolde.

◆ ◆ ◆ Seth Colter Walls, Times writer Do Wagner’s operas feature almost endless melodies? Certainly. But he knew how to write conflict, too — sometimes even in short bursts. Take this climactic scene from Act II of “Lohengrin.” The plot is complex, but even if you don’t know what’s being said, you can feel the heat of the moment: the sorceress Ortrud, near the entrance to a church, barring the arrival of Elsa, there as a bride-to-be. The townspeople in the chorus gasp as these Real Housewives of Antwerp go at it regarding the comparative status of their mates; you may feel yourself in rapt league with those assembled voyeurs as you listen to the mezzo-soprano Christa Ludwig and the soprano Elisabeth Grümmer.

◆ ◆ ◆Celia Applegate, historian Compassion is at the core of “Parsifal,” Wagner’s last and, for many, greatest opera. The music of the prelude connects all living things in its embrace. It’s not heavenly music. It’s music of this world, expressing suffering, struggle, the inevitability of death and the peace of understanding and acceptance. Its slow tempo and gorgeous sounds draw you almost into a trance. But somehow, too, you feel the presence of all things on this earth — and our responsibility to care about it and for it.

◆ ◆ ◆ Morris Robinson, bass “Das Rheingold” is just going along, with ebbs and flows, when suddenly, without warning, this incredibly loud, obtrusive, majestic musical theme “debos” its way into the score. Everyone — within the story and in the audience — realizes that something massive and potentially destructive is about to make an appearance.I’m thinking Incredible Hulk vibes, except Wagner has created a pair of Hulks, the brother giants Fasolt and Fafner. Having played Fasolt several times, I can assure you that the theme music brings the moment into focus, and also gets the singers pumped to go out and mentally invest in their characterization. I make it my goal to ensure that my vocal quality immediately following this fabulous introduction matches the intensity and volume of Wagner’s fabulous orchestration, which consists of extremely heavy brass and pulsating, pounding timpani.

◆ ◆ ◆ Joshua Barone, Times editor One word associated with Wagner is “cinematic,” in part because of his innovations at the Bayreuth Festival Theater — where the stage, surrounded in darkness, is given the focus of a silver screen, and where the hidden orchestra’s sound fills the auditorium like a Dolby system. But I also see film in his patient moments of diegetic music, such as when Tannhäuser returns from the orgiastic Venusberg, freshly earthbound. The orchestra fades, first to a clarinet solo, then seamlessly to an English horn, standing in for the pipe of a shepherd, who sings an a cappella ode until pilgrims pass through with a hymn. Wagner weaves the pipe and chorus, beautifully but with a sense of naturalism: The orchestra doesn’t even come back until Tannhäuser, overwhelmed by what he sees, exclaims, “Praise to You, almighty God!”

◆ ◆ ◆ Javier C. Hernández, Times classical music and dance reporter “Der Fliegende Holländer” is the opera that launched Wagner’s career. He was 29 when it premiered in Dresden, and it is generally regarded as his greatest early achievement, with hints throughout of the dramatic intensity and musical flow that would come to characterize his later works. The rousing “Sailor’s Chorus” from the third act shows his early mastery of grand orchestral and choral sound.

◆ ◆ ◆ Stephen Fry, actor in ‘Wagner and Me’ Who’d present a single block from a pyramid to give a picture of all Egypt? The epic scale of Wagner is surely his signature quality. But here goes: The last five minutes of “Tristan und Isolde” offer one of the most astonishing moments in all art. Echoing the great pounding of the sea by which she stands, Isolde sings herself to death by way of a shattering musical climax. The orgasmic passage is known as the “Liebestod”: love-death. Its ravishing, horrifying rise and fall still astounds. Finally, it levels out across the sands in an exquisite release.

◆ ◆ ◆ Zachary Woolfe, Times classical music editor Five minutes to make you love Wagner, and hate him. At the end of his sprawling comedy “Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg,” a speech from the kindly shoemaker protagonist, Hans Sachs, takes a dark swerve as Sachs warns of foreign invaders who seek to contaminate “holy German art,” his praise of which is taken up by a fervid crowd — a communal celebration turned nationalistic rally. This stirring choral melody was perhaps the first bit of Wagner I loved. But it is one of the moments in his work that for me now mingles thrill and nausea. Here it is conducted in Vienna in 1944 by Karl Böhm, whose complicity with the Nazis was profound.

https://newslastweb.com/5-minutes-that-will-make-you-love-wagner/

1 note

·

View note

Text

FILARMÓNICA DE VIENA

CONCIERTO DE AÑO NUEVO 2021

Son pocos los conciertos que atraen el interés internacional como lo hace el Concierto de Año Nuevo de Viena. Por primera vez sin público presencial, la Filarmónica de Viena recibirá el nuevo año con un concierto dirigido por Riccardo Muti en el Musikverein de Viena. 8 de enero a la venta en CD y digital; el 29 de enero en DVD, BLU RAY y LP.

Resérvalo AQUÍ

El evento se emite a más de 90 países de todo el mundo y es visto por más de 50 millones de espectadores.

El día de Año Nuevo de 2021 Riccardo Muti dirigirá el prestigioso concierto de Año Nuevo por sexta vez (1993, 1997, 2000, 2004 y 2018). Junto a Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti es uno de los directores más activos del Concierto de Año Nuevo desde la época de Lorin Maazel. La estrecha relación artística del director con la Filarmónica de Viena celebra 50 años, casi 550 conciertos y se remonta a 1971. En 2011, este vínculo excepcional llevó a Riccardo Muti a ser nombrado miembro honorario de la Filarmónica de Viena. Esto hace que resulte apropiado no solo conmemorar Italia, sino también el próximo 80 cumpleaños del director y miembro honorario de la orquesta.

Riccardo Muti

Nacido en Nápoles en 1941, Riccardo Muti ha dirigido a las orquestas más importantes del mundo. A lo largo de su extraordinaria carrera, ha trabajado con la Filarmónica de Berlín, la Orquesta Sinfónica de la Radio Bávara; la Filarmónica de Nueva York o la Orchestre National de France, al igual que la Filarmónica de Viena, una orquesta con la que tiene un vínculo especial y con la que ha aparecido en el Festival de Salzburgo desde 1971.

Cuando Muti fue invitado a dirigir el concierto que celebra el 150 aniversario de la Filarmónica de Viena, la orquesta le concedió el Anillo de Oro, un signo especial de afecto otorgado solo a algunos directores. En septiembre de 2010, Riccardo Muti se convirtió en el director musical de la Orquesta Sinfónica de Chicago y fue nombrado músico del Año 2010 por Musical America. Riccardo Muti ha recibido innumerables honores internacionales a lo largo de su carrera. Es Cavaliere di Gran Croce de la República Italiana y receptor del Verdienstkreuz alemán, fue condecorado Oficial de la Legión de Honor por el presidente francés Nicolas Sarkozy y nombrado Caballero del Imperio Británico por la reina Isabel II de Gran Bretaña. El Mozarteum de Salzburgo le concedió su medalla de plata por su contribución a la música de Mozart, y en Viena fue elegido miembro honorario de la Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, la Hofmusikkapelle de Viena y la Ópera Estatal de Viena.

En 2011, Riccardo Muti fue galardonado con dos premios Grammy, fue seleccionado como ganador del codiciado premio Birgit Nilsson, recibió el premio Opera News en Nueva York y fue galardonado con el prestigioso Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Artes de España. Fue nombrado miembro honorario de la Filarmónica de Viena y en agosto de 2011 director honorario vitalicio de la Ópera de Roma. En mayo de 2012, se le concedió el más alto honor papal: el Caballero de la Gran Cruz de Primera Clase de la Orden de St. Gregorio Magno por el Papa Benedicto XVI. En 2016 fue distinguido por el gobierno japonés con la Orden del Sol Naciente, Estrella de Oro y Plata.

La Filarmónica de Viena se remonta a 1842, cuando Otto Nicolai dirigió un "Gran Concierto" con los miembros de la ópera de la corte imperial. Se considera que este evento es el origen de la orquesta. Desde su fundación, la orquesta ha sido dirigida por un comité administrativo elegido democráticamente y trabaja con autonomía artística, organizativa y financiera. En el siglo XX, la Filarmónica de Viena colaboró con Richard Strauss, Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler y con los miembros honorarios Karl Böhm, Herbert von Karajan y Leonard Bernstein. La orquesta ha realizado aproximadamente 9.000 conciertos en todos los continentes desde su creación, y ha presentado las Semanas Filarmónicas de Viena en Nueva York desde 1989 y en Japón desde 1993. La tradición del Concierto de Año Nuevo se remonta a 1941. El primer concierto para celebrar el Año Nuevo tuvo lugar en 1939, pero en esa ocasión se dio el 31 de diciembre. Su primer director de orquesta fue Clemens Krauss, al que siguió en 1955 Willi Boskovsky. Boskovsky dirigió el Concierto de Año Nuevo no menos de veinticinco veces entre entonces y 1979. La lista de directores que han encabezado un Concierto de Año Nuevo incluye a los principales maestros. El Concierto de Año Nuevo fue televisado por primera vez en directo en 1959. La Filarmónica de Viena considera el Concierto de Año Nuevo como un mensaje musical al mundo que se ofrece con un espíritu de esperanza, de amistad y de paz al comienzo del Año Nuevo. Las grabaciones del Concierto de Año Nuevo están entre los lanzamientos más importantes del mercado clásico. Sony Classical quiere asegurarse de que el Concierto de Año Nuevo esté disponible para un amplio público internacional. La grabación en directo del Concierto de Año Nuevo 2021 se publicará en CD y formato digital (lanzamiento internacional el 8 de enero), al igual que en DVD Blu-Ray y LP (29 de enero).

Concierto de Año Nuevo 2021: Listado de obras musicales que se interpretarán

FRANZ VON SUPPÈ 1819–1895

Fatinitza: Marsch*

JOHANN STRAUSS II 1825–1899

Schallwellen op. 148*

Ondas sonoras · Ondes sonores

Walzer

Niko Polka op. 228

Polka schnell

JOSEF STRAUSS 1827–1870

Ohne Sorgen op. 271

Sin cuidado · Sans souci

Polka schnell

CARL ZELLER 1842–1898

Grubenlichter-Walzer*

Davy Lamps · Valse de la lampe de mineur

sobre Motivos de la Operetta Der Obersteiger

CARL MILLÖCKER 1842–1899

In Saus und Braus*

Vivir la vida · Mener la belle vie

Galopp sobre los motivos de la Opereta Der Probekuss

FRANZ VON SUPPÈ

Dichter und Bauer: Ouvertüre

Poeta y Campesino: Obertura

Ouverture de Poète et Paysan

KAREL KOMZÁK II 1850–1905

Bad’ner Mad’ln op. 257*

Chicas de Baden · Filles de Baden

Walzer

JOSEF STRAUSS

Margherita Polka op. 244*

Polka française

JOHANN STRAUSS I 1804–1849

Venetianer-Galopp op. 74*

JOHANN STRAUSS II

Frühlingsstimmen op. 410

Voces de primavera · Voix du printemps

Walzer

Im Krapfenwald’l op. 336

Polka française

Neue Melodien Quadrille op. 254

Nuevas melodías · Nouvelles mélodies

Kaiser-Walzer op. 437

Vals del Emperador · Valse de l’empereur

Stürmisch in Lieb’ und Tanz op. 393

Tempestuoso en el amor y la danza

Impétueux en amour et dans la danse

Polka schnell

* Primera interpretación en un concierto de Año Nuevo en Viena

Vienna Philharmonic

Official Website:

http://www.wienerphilharmoniker.at/en

Official Facebook Page (352k Likes):

https://www.facebook.com/ViennaPhilharmonic

Official Twitter Account (10k Follower):

https://twitter.com/Vienna_Phil

Official Vevo Channel:

http://www.vevo.com/artist/wiener-philharmoniker

0 notes

Text

Can Baltimore Save Its World-Class Orchestra?

Baltimore recently lost many civic donors recently. Baltimore Symphony Orchestra musicians earn a base pay of $83,000 for 52 weeks, which is not financially tenable. What would you do if you were the executive director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, you proposed reducing base pay from 52 weeks to 42 weeks, and the musicians strongly refused, and you already borrowed $2.3 million from its endowment, in part to make its May 31 payroll: (1) continue to negotiate although it seems hopeless, (2) lock out the musicians until they agree on the pay reduction? Why What are the ethics underlying your decision?

When violent unrest spread through the streets of Baltimore in 2015 after the death of Freddie Gray, an African-American man who suffered a spinal injury while in police custody, the Baltimore Orioles took the extraordinary step of playing in an empty stadium, barring fans because of safety concerns.

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra sent a different message: Its musicians gathered on the sidewalk in front of their concert hall to perform Handel, Bach and Beethoven to a crowd of hundreds seeking solace at a scarring moment.

The musicians are now back on that same stretch of sidewalk — walking a picket line. On June 17, the orchestra’s management, citing fiscal pressures, locked the players out without pay to try to pressure them to agree to a contract guaranteeing fewer weeks of work. The sounds at the hall last week were of protesters’ drums, bullhorn chants and passing cars honking support.

The showdown raises all too familiar questions about how venerable ensembles will survive, let alone thrive, in an era when classical music faces stiff financial headwinds. But the labor strife has been especially dispiriting in Baltimore, a city whose woes need no recitation but which had always seen its orchestra as an embodiment of its pluck.

Founded in 1916 by the city itself, as a branch of its municipal government, the orchestra later reorganized along more traditional lines. Since 1982 it has played at Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, a rounded, red-brown brick building a short walk from Pennsylvania Station that was constructed during an era of expanding ambitions.

Mr. Meyerhoff was once the orchestra’s biggest benefactor, and his family remains a major supporter. But much of the area’s philanthropy today is directed to education, health and economic issues, in a city that faces deep pockets of poverty and problems including lack of heat in some schools last year and a water main break last month that left public housing residents without waterfor days.

“For the small donor, there are so many other crying needs,” said Heather Joslyn, a former senior editor at The Chronicle of Philanthropy who lives in Baltimore.

Even with inadequate support, the Baltimore Symphony has managed to punch above its weight in recent years. Under the musical leadership of Marin Alsop, the only female music director of a major American orchestra, it has embraced more daring programming, made acclaimed recordings, and, last year, toured Europe. And it has creatively reached out to its community, starting OrchKids, which offers music instruction, homework tutors, after-school snacks and dinner to more than 1,300 children in neighborhoods that struggle with poverty and violence.

“It’s horrible,” lamented Marge Penhallegon, 76, a retired elementary school music teacher who began taking her students to hear the orchestra more than 50 years ago and later became an active supporter and volunteer, as she watched the musicians march outside the hall. “This city needs the culture it can provide. It fills your soul.”

The players warn that the proposed cuts — which would lower their base pay to less than half of what it is at the National Symphony Orchestra, in neighboring Washington — would weaken their ties to the community and make it harder for them to attract and retain talent. “We’re losing musicians to better-paying orchestras,” Greg Mulligan, a violinist who is one of the two chairmen of the orchestra’s negotiating committee, said.

But management has said the cuts are desperately needed. It said that the orchestra faced such a cash crunch in May that it had to borrow $2.3 million from its endowment, in part to make its May 31 payroll — its second large borrowing from the endowment in recent years. Peter T. Kjome, the orchestra’s president and chief executive officer, said in an interview that a recent strategic planning process had determined that “our current financial model could not support the mission and vision of the Baltimore Symphony as currently conceived.”

In recent years orchestras around the country have argued that they must curb their rising costs if they are to survive in a new era, in which they now rely on philanthropic donations for more of their annual revenue than ticket sales.

Some orchestras have gotten smaller. Others, including thePittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and, this year, the storied Chicago Symphony Orchestra, have shifted from pensions to plans similar to a 401(k).

And some, including the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and the St. Louis Symphony, have moved away from 52-week contracts, saying that there was not enough demand for year-round concerts. The length of the season has become a flash point in Baltimore: Management wants to reduce the musicians’ paid weeks of work to 40, from the current 52.

The musicians pointed out that their current year-round base salary in Baltimore, nearly $83,000, is already lower than the base salaries at those orchestras in Detroit and St. Louis, which have shorter seasons. The reduction in weeks, coupled with a demand that they contribute more for health coverage, would cut their pay by roughly a fifth, making it harder, they say, to attract top talent.

Jesse Rosen, the president of the League of American Orchestras, said that the trouble in Baltimore was especially dispiriting given how forward-looking the ensemble has been.

“It’s one thing if you look at an orchestra that’s kind of treading water artistically,” he said in an interview. “But that’s not the case with Baltimore. They’ve really been at the forefront.”

Joseph Meyerhoff II, a trustee of the orchestra’s endowment, recounted last week how Baltimore had changed since the years when his grandfather, a wealthy developer, was chairman of the board.

He rattled off a list of corporations and local banks that were lost to mergers, sales, closures and headquarters relocations — the disappearance of a network of institutions that used to pitch in to cover the orchestra’s deficits or extend credit. “They understood the civic responsibility that corporations have,” he said.

There is new wealth in the region, and plenty of philanthropy, though it is mostly aimed elsewhere. Last year Johns Hopkins University received a $1.8 billion donation from one alumnus, Michael Bloomberg, to support financial aid, including $50 million for students at the university’s music school.

When Mr. Meyerhoff’s family recently offered a $4 million challenge grant to match large donations to the orchestra’s endowment, he said, they met with many of the area’s wealthiest citizens and foundations. But they got no offers for any single gifts of more than $250,000. Now they are trying again, offering a $5 million challenge grant, on the condition that $45 million is raised for the endowment.

Some of the city’s cultural institutions have folded: The Baltimore Opera Company, established in 1950 and once led by the soprano Rosa Ponselle, with stars including Plácido Domingo, Birgit Nilsson and Beverly Sills, shut down in 2009. Last year Concert Artists of Baltimore, an orchestra and chorus, closed after three decades.

In 2005 the Baltimore Symphony expanded into a second home: the Music Center at Strathmore in North Bethesda, Md., a suburb of Washington, where it plays between 30 and 40 concerts a year. While attendance there has been fairly strong, the orchestra has not succeeded in tapping as many new donors in the Washington suburbs as it had hoped.

The orchestra has been raising money, but not as much as officials say is needed. (It is possible, though: this spring the Philadelphia Orchestra, whose fiscal woes drove it to bankruptcy in 2011, announced a $55 million gift.)

The current crisis struck in May, when orchestra officials learned that they would probably not be getting $1.6 million in emergency state aid that Maryland lawmakers had approved, but which the governor, Larry Hogan, has been reluctant to release. The orchestra canceled its summer season, which it had only recently announced, and soon after locked out the players.

The lockout is a major hardship for many of the musicians, who face mortgage payments, student loan payments for younger players, and children’s tuition payments for older ones. Lisa Steltenpohl, 35, its principal violist, said that she had been looking into taking out a home-equity loan to make ends meet. Schuyler Jackson, a 27-year-old bassoonist, said that he had monthly payments of $450 on the $32,000 instrument he bought to play in the orchestra, on top of steep student loans. “It’s really scary,” he said.

Music directors generally try to stay above the fray in labor disputes. But when asked about the lockout, Ms. Alsop sounded a note of caution.

“We need to invest in the world-class institutions we do have in Baltimore rather than cutting the things that make our city great,” she said in an email. “I urge all sides to engage in constructive dialogue to ensure that Baltimore continues to have the great orchestra it needs and deserves.”

0 notes

Text

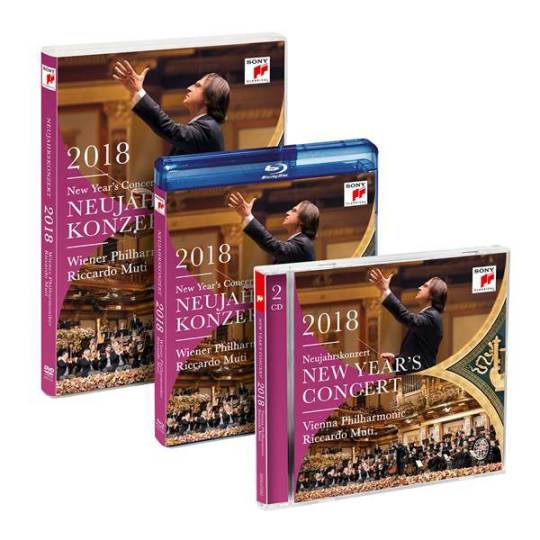

FILARMÓNICA DE VIENA

CONCIERTO DE AÑO NUEVO 2018

Pocos conciertos pueden presumir de generar un interés tan grande como el Concierto de Año Nuevo de Viena. La Filarmónica de Viena dará la bienvenida al 2018 bajo la batuta del laureado director Riccardo Muti en concierto de gala en el magnífico escenario del Hall Dorado del Musikverein de Viena. Ya disponible para reserva.

¡Resérvalo aquí!

En 2018 Riccardo Muti dirigirá este prestigioso concierto de Año Nuevo por quinta vez (anteriormente en 1993, 1997, 2000 y 2004). Junto a Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti es uno de los directores que más se han relacionado con el Concierto de Año Nuevo desde la época de Lorin Maazel. La estrecha relación artística con la Orquesta Filarmónica de Viena celebra 47 años, 500 conciertos y se remonta a 1971. En 2011, este excepcional vínculo fue reconocido nombrando al director Miembro Honorario de la Filarmónica de Viena.

Riccardo Muti Nacido en Nápoles en 1941, Riccardo Muti ha dirigido las orquestas más importantes del mundo. A lo largo de su extraordinaria carrera ha actuado con la Filarmónica de Berlín, la Orquesta Sinfónica de la Radio de Baviera, la Filarmónica de Nueva York y la Orquesta Nacional de Francia además de la Filarmónica Viena, con la cual ha mantenido un vínculo especial y con la cual ha actuado en el Festival de Salzburgo desde 1971. Cuando Muti fue invitado a dirigir la Filarmónica de Viena en su concierto 150 aniversario, la orquesta le ofreció el Anillo Dorado, un signo especial de cariño y afecto, solo obsequiado a pocos directores. En septiembre de 2010, Riccardo Muti se convirtió en el Director musical de la Orquesta Sinfónica de Chicago y fue nombrado Músico del Año 2010 por Musical America.

Riccardo Muti ha recibido numerosos premios internacionales a lo largo de su carrera. Es Cavaliere di Gran Croce de la República Italiana y receptor de la Verdienstkreuz alemana; ha recibido la condecoración de Oficial de la Legión de honor por parte del expresidente francés Nicolas Sarkozy y fue nombrado Caballero honorario del Imperio Británico por la reina Elizabeth II en Gran Bretaña. El Mozarteum de Salzburgo le concedió la medalla de plata por su contribución a la música de Mozart, y en Viena fue elegido miembro honorario de la Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, la Hofmusikkapelle de Viena y la Ópera Estatal de Viena.

En 2011, Riccardo Muti recibió dos Premios Grammy, fue elegido receptor del prestigioso Premio Birgit Nilsson, recibió el Premio de Opera News en Nueva York y también el deseado Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Artes en España. Fue nombrado miembro honorario de la Filarmónica de Viena en 2011 y director honorario de por vida de la Ópera de Roma. En mayo de 2012, recibió el mayor honor papal de manos del papa Benedicto XVI: el nombramiento como Caballero de la Gran Cruz de la Orden de San Gregorio. En 2016 su talento fue reconocido por el gobierno japonés con la Orden del Sol Naciente, estrella de oro y plata.

La Orquesta Filarmónica de Viena se remonta al año 1842, cuando Otto Nicolai dirigió un Grand Concert con todos los miembros de la ópera de la corte Imperial. Este evento es considerado como el origen de la orquesta. Desde su fundación, la orquesta ha sido dirigida por un comité administrativo elegido democráticamente y funciona con autonomía artística, organizativa y financiera. En el siglo XX la Filarmónica de Viena ha contado con importantes colaboraciones artísticas de Richard Strauss, Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler y – después de 1945 – de los directores honorarios Karl Böhm, Herbert von Karajan y Leonard Bernstein. La orquesta ha dado aproximadamente 7.000 conciertos en todos los continentes desde su creación, y ha presentado las “Semanas de la Filarmónica de Viena” en Nueva York desde 1989 y en Japón desde 1993. La tradición del Concierto de Año Nuevo comenzó en 1941. El primer concierto con el que se comenzaría el Año Nuevo iba a tener lugar en 1939, pero en aquella ocasión se dio el 31 de Diciembre. Su primer director, Clemens Krauss, fue sucedido en 1955 por Willi Boskovsky, que dirigió este evento 25 veces hasta 1979. La lista de directores invitados que han dirigido el Concierto de Año Nuevo desde entonces incluye a los más grandes maestros. En 1959 se transmitió por primera vez en directo por televisión. La Filarmónica de Viena considera su concierto como un saludo musical y un mensaje de esperanza y paz que envía al mundo entero el día que comienza un nuevo año. Sony Classical tiene como propósito asegurar que el Concierto de Año Nuevo llegue a un amplio público internacional.

La grabación en directo del Concierto de Año Nuevo 2018 estará disponible en formato CD el 12 de Enero, en digital el 6 de Enero. En formato DVD y Blu-ray (26 de enero), en vinilo (16 de febrero) y LP (16 de febrero).

Concierto de Año Nuevo 2018: Listado de obras

Johann Strauß II: Der Zigeunerbaron: Einzugsmarsch El barón gitano: Marcha de entrada

Josef Strauß: Wiener Fresken op. 249* Frescos vieneses

Johann Strauß II: Brautschau op. 417* Marcha nupcial

Johann Strauß II: Leichtes Blut op. 319 Light of Heart

Johann Strauß I: Marienwalzer op. 212* El vals de María

Johann Strauß I: Wilhelm Tell Galopp op. 29b*

Franz von Suppé: Boccaccio Overture*

Johann Strauß II: Myrthenblüten op. 395* Flores de mirto

Alphons Czibulka: Stephanie-Gavotte op. 312*

Johann Strauß II: Freikugeln op. 326 Balas mágicas

Johann Strauß II: Geschichten aus dem Wienerwald op. 325 Cuentos del bosque de Viena

Johann Strauß II: Festmarsch op. 452 Marcha de festival

Johann Strauß II: Stadt und Land op. 322 Ciudad y campo

Johann Strauß II: Un ballo in maschera op. 272 Ein Maskenball · Un baile de máscara

Johann Strauß II: Rosen aus dem Süden op. 388 Rosas del sur

Josef Strauß: Eingesendet op. 240 Carta al editor

* Primera vez en el Concierto de Año Nuevo en Viena

Reserva el Concierto de Año Nuevo 2018 aquí.

Filarmónica de Viena Web oficial: http://www.wienerphilharmoniker.at/en Facebook): https://www.facebook.com/ViennaPhilharmonic Twitter: https://twitter.com/Vienna_Phil Vevo: http://www.vevo.com/artist/wiener-philharmoniker

Riccardo Muti Web oficial: http://www.riccardomuti.com/en/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RiccardoMutiOfficial/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/MaestroMuti Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/riccardomutichannel

0 notes