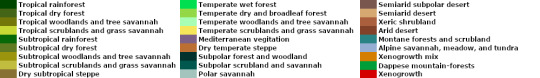

#biomes of sogant raha

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

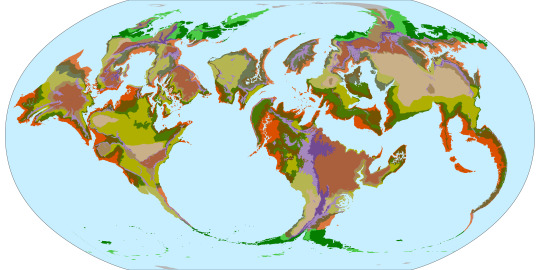

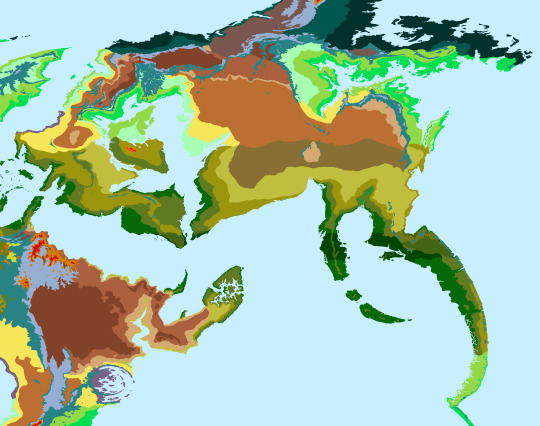

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Xenogrowth and Xenogrowth Mix

[Map: major xenogrowth belts in central Rezana, showing full xenogrowth in red and xenogrowth mix in orange]

The recent biogeographical history of Sogant Raha can be divided into two major phases. The first of these phases concerns the planet as it was when the first Exiled arrived in orbit from a distant star. Driven by a soteriology that had grown up between legends of a lost paradise from which they had originated, and a future paradise embodied in a far-off exoplanet, whose atmosphere betrayed signs of a rich biosphere in its spectroscopic signature, an immediate debate began on what form human settlement on the new world would take.

This debate coalesced around two major ideologies that were in concurrence on many major issues, but which differed on a subtle but important point. The Instrumentalists sought to integrate humanity into this alien biosphere; they believed that human and Sogantine life should co-exist. The Renewalists sought to conform to the rigors of the Sogantine biosphere; they believed that the stewardship of Paradise was the highest priority. Both factions were extraordinarily conscious of the dark myths which stretched back into the first days of the Exile long ago, that said humanity was driven to flight, and the first Paradise laid waste because of the works of human hands. Both recognized that, in a cosmos in which living worlds seemed to be painfully rare, this was an opportunity that must not be squandered.

But despite the apparent consonance between these groups, the tension on what degree of importance to grant the human settlement of Paradise rapidly grew, and nearly resulted in civil war aboard the Ammas Echor. Two events prompted reconciliation. First, a joint surface expedition returned with the news that the native biosphere was safe for humans to inhabit, with little risk of disease spreading from humans to the xenobiota or vice-versa. Second, the Great Record, a genetic encyclopedia containing the whole genome of a vast number of Terran lifeforms and information on how to reconstruct living organisms from that data, was discovered carved into the bones of the Ammas Echor. This second discovery in particular threw the plans of both the Instrumentalists and Renewalists into confusion, and the Archivists, a third faction consisting of the heavily genetically and cybernetically altered caste responsible for shepherding the Ammas Echor during its millennia-long flight between the stars that had until then remained aloof, stepped in to broker a peace.

Under the watchful eye of the Archive, human settlement of the surface would begin, and steps would be taken to start the rebirth of terrestrial species that had been extinct for hundreds of thousands of years; but both would proceed along highly controlled and extremely cautious timetables, confined to small designated areas of the surface. Thorough computer simulations and carefully controlled ecological experiments would be undertaken before any expansion was considered; and the human population would remain tightly controlled for centuries to come. This was understood to be a price well worth paying to safeguard against the possibility of dealing irreparable harm to a unique world.

But not all the settlers were happy with this outcome. In particular, a small circle of radical Instrumentalists, augmented by geneticists and ecologists who felt that the Archive was suppressing legitimate scientific inquiry to keep the peace, began a rogue program of species-resurrection, believing that they could accelerate the Archive’s timetable considerably, without seriously endangering the native ecosystem. Working at Khoda Station, a weather observation post far to the southeast of the human colony, they started with various flowering plants before moving on to insects, birds, and (their crowning achievement) bottlenose dolphins. When this rogue operation was discovered, the Archive arrested everyone involved and ordered the destruction of Khoda Station and the sterilization of the surrounding land, to prevent the escape of any potential invasive species. One scientist who refused to evacuate was killed; but the dolphins, partially forewarned by the agitation of the humans, escaped into the open sea.

Further disruption to the program of settlement occurred two generations later; an epidemic of delirium, delusion, and madness began to sweep through first the planetside colonists, and then those who remained aboard the Ammas Echor as well. Only too late, the microbiologists of the Archive realized they had incompletely misunderstood the biosphere of Sogant Raha. Besides the familiar orders of cellular life, which resembled the biology of terran life in their structure, if not their particulars, there was a second order of life that was radically different. Non-cellular, chemically distinct--and in fact much more akin to human biology in composition--this order was principally microscopic, was found as a commensalist throughout the native biosphere, and had begun to colonize the endobiota, humans and the resurrected terran species. What was benign in the xenobiota that had co-evolved with the acytic clade had, for unknown reasons, begun to cause adverse reactions in humans. Led by a brilliant scientist named Kaituro, the Archive’s microbiologists raced to solve the underlying biological mysteries before the plague claimed the lives of the entire colony.

One morning, Kaituro’s colleagues awoke to a mystery: they found Kaituro in an isolation chamber meant for sterile experiments, hooked up to monitors for his vital signs; his body was alive and breathing, but he was brain-dead; the structure of his cerebellum had been destroyed, essentially liquefied, and replaced with a thick slurry of acytic microorganisms and neural protein. An IV in his arm indicated he had injected himself with a compound dangerous to humans but known to promote acytic growth, and a data feed connected to a port in his arm suggested he had been monitoring the activity of the acytes in his bloodstream for an unknown reason; but the data recorder was damaged, and the information unrecoverable. Whatever experiment he had been running was a failure; his body was incinerated that evening.

In subsequent months, the plague reached a fever pitch. Madness claimed the Ammas Echor itself, whose pilots drove it out of orbit and into the sea, a colossal loss for the colony which was still extensively reliant on the technology and fabrication facilities the ship provided. The planetside Archive strove to maintain peace, but panic and anger eventually caused a total political collapse; humans began to spread out across the planet, no longer unified by a single plan or purpose, and they brought with them various resurrected endobiota, which began to integrate themselves into the native ecosystem.

This is the essence of the first phase: a continuous history with the pre-human ecology of Sogant Raha, albeit with the gradual introduction of new endobiota. Although the technology used to resurrect endobiota was lost within a few centuries of the Ammas Echor’s destruction, by that time a huge portion of the Great Record had been transcribed, as it were, into living species. Some endobiota subsequently went extinct, outcompeted by xenobiota that were better adapted for Sogant Raha’s climate and soil, while others found new niches all their own. Oceanic endobiota were much less successful on the whole; besides the bottlenose dolphin, some species of kelp, and various species associated in coral reef ecosystems (which thrived in Sogant Raha’s warm, shallow seas), most oceanic endobiota simply could not compete with native life, and were not successfully resurrected.

Among some endobiota, a curious change occurred: some--but by no means all-organisms colonized by the acytes began to undergo radical changes in their morphology and behavior, changes that failed to be passed on to the offspring if the acytes were purged from them at an early stage of embryonic development. Rumors of monsters in the wilderness were followed by captured specimens of strange and dangerous beasts; and eventually, these were followed by bloody live encounters with humans. The natural world seemed to be turning against humanity.

Worse was to come: for a long time, it seemed that the human body had adapted to the presence of the acytic commensalists that had caused the original epidemic of madness; however, some centuries later, this epidemic returned in a new form. Now tending to cause primarily ataxia, tremors, insomnia, and mood swings, new outbreaks of acytic disease began to occur in a way that suggested they were caused by proximity, though no infectious agent could be identified besides the acytes themselves, which were present in the healthy and the sick alike.

At the same time, tensions were rising among states in the south of the world; investigation of the acytes showed that they had evolved a complicated signalling mechanism that stored a fantastic amount of energy, meaning that if they could be concentrated together in a high enough density, primed with the right signals and fed on the right substrate, they could be made into a powerful weapon.

Although this technology was abandoned as too difficult to control, and likely to promote vicious reprisals from competing states, knowledge of the technology spread to a transnational political faction that had come to understand the native biosphere as wholly hostile to continued human existence. Reports of ghostlike apparitions and many-limbed monsters composed of cold fire killing hundreds and shattering buildings were now becoming commonplace, coming where the new epidemic was most concentrated. Building on that earlier research, and using what was left of the sophisticated technology of the first colonists, they attempted to construct a machine that would permit them to selectively turn the acytic signalling mechanism against the native biosphere of Sogant Raha.

They succeeded beyond their wildest imaginations--in fact, they set off a cascading reaction that could not be stopped, and which began to destroy all native life on the planet. This era, dubbed “the Burning Spring,” resulted in countless acres of dead savannah and jungle that were consumed by wildfire, throwing thick smoke into the planet’s upper atmosphere, releasing vast quantities of carbon dioxide, and resulting in the deaths of millions due to famine and sickness. But as the Burning Spring passed over the world, endobiota--and endoflora in particular--seemed to revel in the destruction, rapidly claiming the territory yielded up by the native life.

It took many millennia for the global climate and human population to stabilize again; by the time it did, humanity could scarcely remember a time before, and the planet’s surface was now utterly transformed. This is the essential portrait of the second phase of Sogantine biogeography: instead of being dominated by xenobiota, with a small presence of endobiota and occasionally dense pockets surrounding human settlements, endobiota dominated the land-based biosphere, with significant intrusions into the ocean along continental shelves and in the upper water column, while the xenobiota was confined to dwindling refugia, mostly in the continental interiors, and the deep sea.

In the many thousands of years since the Burning Spring, the size of those refugia has continued to shrink. As they have dwindled, they seem to somehow become more conscious of the threat the alien intruders represent, and more unsparing in their defense. In those regions of xenogrowth mix, which seem to spread outward from and be supported by, the unmixed xenogrowth regions in their hearts, human life is impossible for any length of time. Both endo- and xenoflora here are unaccountably toxic, unusual and aggressive animals are found that are known nowhere else, novel viruses cause fulminant cancers and keratinous growths on the skin, and acytes within the human body seem to go haywire, causing neurological disruptions, hallucinations, and necrotic abscesses. It is rumored that beyond this nightmarish borderland, the heart of these refugia are tranquil and beautiful in comparison--remnants of a world once yearned for by humanity and now long-forgotten. But few have survived long enough to explore these regions.

Since these regions represent areas not available to use or exploration by humans, maps of Sogant Raha’s climate and biomes usually do not differentiate between types of xenogrowth or xenogrowth mix; the same colors represent forestlike, savannahlike, and grassland-like conditions.

#biomes of sogant raha#sogant raha#tanadrin's fiction#the timescales we're talking about here are long#tens of thousands of years in some cases#but still far too short for much in the way of darwinian evolution#the acytic signalling network pervades the entire planet even post-Burning Spring#and is responsible for a lot of these adaptations by means of epigenetic manipulation#of both endo- and xenobiota

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

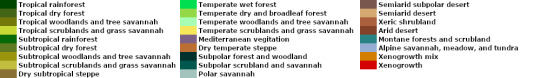

Bonus map: the biomes of Sogant Raha on the eve of the arrival of the Ammas Echor.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Central Vinsamaren

Vinsamaren's climate and vegitation are strongly defined by the Arduinn Mountains, a vast range of uplifted sedimentary and metamorphic rock driven up by the collision of the West Vinsamaren Plate and the East Vinsamaren Plate. Among both the youngest and the highest mountains on Sogant Raha, the Arduinn Mountains bisect the continent from just north of the equator down past 60° S, well into the polar regions, with profound effects on both patterns of prevailing winds and rainfall on either side.

To the east, in the subtropical zone, the Arduinn rain shadow has contributed to the formation of the massive East Vinsamaren deserts, which are further anchored by the high pressure ridge at 30° S, the result of cool, dry air of both the Hadley and Ferrell cells sinking down from higher altitudes. South of the divergence zone, another rain shadow effect produces a large grassland region on the opposite side of the mountains, in further Tarun; this area is not quite as dry as the Great Deserts, thanks to the mountains to the north deflecting some moisture-bearing air to the southeast.

Northwestern Vinsamaren is dominated by tropical and subtropical forests; the windward southeast enjoys a more moderate, temperate climate.

The dense jungles of the northeast, plus the high Sayyedhar Mountains, and the extensive xenogrowth refugium on the northern margin of the Kelrus Plateau, effectively cut the northwestern coast of Vinsamaren off from the rest of the continent. Thus, culturally and politically, Vinsamaren has historically been divided into approximately five major geographical subdivisions: Sayyedhar (the northwestern coast); Velannu and the north desert margin; the south desert margin, the Gelar Sea, and the southeast; the southwestern grasslands; and Lende and the northwestern jungles.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

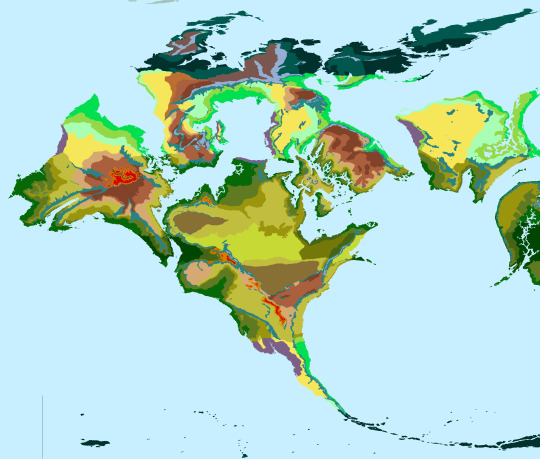

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Western Hemisphere

What we might call for lack of a better term "the western hemisphere" of Sogant Raha is composed of three smaller continents arranged around the Taicun Sea. They are Sarial, in the north (whose large southeastern subcontinent is Adwera); Rezana, in the south; and Karei, in the west.

Sarial is crossed by two major orogenic belts, one in the north and west, and one which descends the west coast of Adwera, cuts across the subcontinent in the region of Thana, and then follows the east coast south. Both lie principally within the temperate zone, creating large rain shadows to their west. Sarial is characterized therefore by relatively narrow, wet coastal strips, and a dry interior,

Rezana lies directly on the equator, and so by rights should be a continent of sprawling, humid jungles. And some tropical rainforests are found on the continent, especially in the far west--but the interior of the continent, although not quite as dry as Sarial, is still dominated by large grassland and steppe regions. Mountains (again, not as high as Sarial's), and large upwind continental landmass, limit the amount of moisture Rezana's interior receives. Still, prevailing winds do periodically carry rainstorms down from the Taicun Sea, and keep the heart of the continent from becoming a single large desert. If the Taicun sea were to dwindle in a future geological era, central Rezana would quickly become a vast, Sahara-like wasteland.

Karei has a very rugged topography, which combined with its higher latitude makes its interior the very dry desert that Rezana is not. Its coasts, however, are covered in lush forests; human settlement is particular dense in the east, where the population is part of the greater Taicun Sea cultural sphere, and in the south, where the people have a strong connection to the peoples of southwestern Rezana.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Altuum

[Top: biomes of Altuum. Bottom: Major geographic subregions of Altuum labeled for reference.]

Altuum is by far the largest continent on Sogant Raha, containing both some of the planet's most densely populated regions and its most inhospitable environments.

Beginning in the southwest, Awlei and Nebressa are verdant subtropical regions that represent some of the oldest areas of human settlement on the planet. Prevailing winds off the Nebretzi Sea create thick forests on their western coasts, while the eastern half of these regions, sheltered by low mountains, are a little drier. The great inland sea keeps inner Altuum far more moderate in climate than it would otherwise be, and gives the large island of Iranda a fairly hospitable environment.

The northwestern and northern portion of the continent are dominated by a large cordillera that stretches almost to the north pole; these mountains create a large rain shadow in the inner regions of the continent. The Kurskanda Desert is particularly harsh, cut off from both the north and south coasts by high mountains, and is one of the driest regions on the planet. On the far side of these mountains lies the peninsula of Jenosha, which is by contrast wet and heavily forested.

The Conn Plain and East Altuum not only lie under the dry, high-pressure zones of the descending convection currents from the upper atmosphere, but are sheltered from rain-bearing prevailing winds by smaller mountain ranges. These factors together contribute to the formation of a large steppe region, which is historically a major barrier to the movements of peoples between western Altuum and the inland sea on the one hand, and the eastern coast of the continent on the other.

Most exchange of people and goods is, instead, by sea; prevailing winds in the tropics carry ships from Nebressa and eastern Vinsamaren east, while further south winds in the opposite direction carry ships west, particularly to the cities of southeast Vinsamaren and the Gelar Sea. The whole oceanic region enclosed by the bulk of Altuum to the north, the Windlands to the east, and Vinsamaren to the West thus forms a major network of cultural and commercial exchange, almost entirely irrespective of the era of Sogantine history in question.

The Windlands themselves have a subtropical climate not too dissimilar from the western coast of Nebressa; ports on the leeward coast connect to trade routes that span the whole eastern coast of Altuum, and which connect to western Karei, and ultimately to southwestern Rezana, on the far side of the Ehyran Ocean.

Note that East Altuum is home to a unique biome without parallel elsewhere on Sogant Raha, or on Earth: the mountain-forests of the Dappese.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

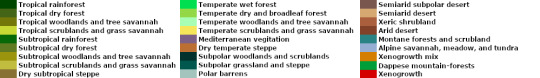

Bonus map: a global overview of the biomes of Sogant Raha, Robinson projection.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Subpolar Biomes

[Above: northern and southern subpolar climates. Subpolar boreal/austral forests are shown in dark green; subpolar boreal/austral woodlands and scrublands are shown in light green; semiarid subpolar deserts in tan.]

The cool circumpolar winds and the warmer air of the mid-latitude Ferrel cells converge at about 60 degrees north and south; on the windwards coasts these prevailing winds support cool subpolar forests. These forests are not as dense as their subtropical counterparts: insolation is much weaker at high latitudes, and the cooler air bears less moisture. Evergreen trees and shrubs prevail, but not to the extent of terrestrial taiga. Sogant Raha's subpolar forests are neither as dense nor as extensive as Earth's taiga, nor do they reach similar extremes of temperature.

Because the cooler polar air carries less moisture inland, the subpolar forests soon give way to subpolar woodlands or scrubland, which are characterized by smaller and much more dispersed shrubs and trees, and are home to numerous grazing animals. Together these biomes have supported large numbers of nomadic and semi-nomadic hunters almost since the beginning of human settlement on Sogant Raha, and the creation of distinctive circumpolar cultures which extend along the coasts and islands found in both regions.

In the immediate rain shadow areas, predominantly in northern Altuum and Sarial, extensive cool, semiarid deserts have formed. These regions support minimal human population, but are notable for several unique varieties of lichen found nowhere else on the planet.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Tropical forests, alpine and polar savannah

Tropical forest

Sogant Raha is comparable in size and rotation speed to Earth; therefore, it has the same number of atmospheric cells, i.e., two polar cells, two Ferrell cells, and two Hadley cells. Like Earth, the zone between the two Hadley cells is a major convergence zone for prevailing winds bearing warm, moist air toward the equator. Near the equator, that air cools, releasing its moisture, and rises; thick tropical forests are produced, with rainforests dominating the lowlands and coasts, and dry tropical forests with a distinct rainy season dominating the highlands and inland regions.

Sogant Raha's lower axial tilt reduces the astronomically-defined tropics considerably; since the planet is overall a little drier and atmosphere a little thinner, the climactic tropics are similarly reduced as well. The large rain shadow produced by the Arduinn Mountains and the Kelrus Plateau means there are no tropics on the leeward part of Vinsamaren, and the large continental landmass of Rezana limits the region of tropical forest in the eastern part of that continent to an area of orographically-induced precipitation between the lowlands and the mountains.

One feature of the tropical and subtropical zones that Sogant Raha lacks entirely are monsoon forests. Earth's monsoons are a seasonal phenomenon, driven by the shift of the intertropical convergence zone with the changing seasons. Sogant Raha's axial tilt is much smaller, as are its seasonal variations in temperature; the intertropical convergence zone moves very little throughout the year.

[Above: the major tropical forest regions of Sogant Raha, from west to east: south Karei, the Rocallan jungle, western Lanai, the Great Vinsamaren Jungle, southeast Deirama, the Jungle of Tigers, Kuj, and the northern Windlands]

Alpine savannah

"Alpine savannah" is here a catchall term for all mountain regions above the treeline, whose height varies with latitude. The largest alpine savannah regions are to be found in the Arduinn Mountains and on the Kelrus Plateau; even though much of these highlands are located on or near the equator, they are a region of fierce tectonic uplift, driven by the convergence of the eastern and western Vinsamaren plates.

Sogant Raha is not currently in an ice age, and though its global temperature does vary considerably over geological timescales, it does not have the same semi-regular cycle of glaciation that the Earth does. Thus, it has no permanent ice cover even in high mountains, and no permanent polar ice.

[Above: the major alpine savannah regions of Vinsamaren and Altuum]

Polar savannah

Between the slightly warmer climate and the smaller amount of circumpolar land, Sogant Raha's poles are positively balmy comared to, say, Antarctica. But they're still cold compared to the rest of the planet and comparatively dry; and of course they get much less sunlight. Within and near the small polar circles, a "polar savannah" biome dominates, which is characterized by a lack of tree cover, low precipitation, and plant life adapted to long periods of winter darkness. These regions are similar to Earth's tundras, but except at high altitudes, they lack a permafrost layer.

[Above: the small region of polar savannah at the northern tip of Altuum, near Sogant Raha’s north pole.]

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

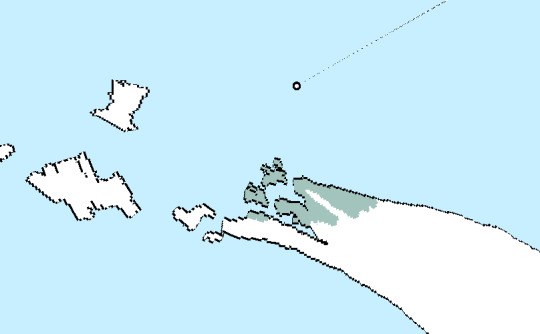

Biomes of Sogant Raha: The Mountain-Forests

[Above: Southeastern Altuum, with the larger Dappese biogeographical region in light green, and the “mountain-forests” in dark green.]

Dappese: dap khu, “true forests;” Larian: gobale, “big forests;” Seqqel: hovalla, “great forests;” Masari: shinsen, “god-forests;” Toschek: dirkabiyar, “green fog mountains”

Outside of the (now greatly reduced) region of xenogrowth, almost all biomes on Sogant Raha have some kind of terrestrial analogue, dominated by endobiota not much different from those common on the Earth when the Exiles departed millennia ago. One unique region, however, are the the forests of Dap Mbeki and Dap Ngara, home of the Dappese people. Much of the surrounding region is subtropical woodland and forest, watered by warm prevailing winds from the southwest that bring masses of moist air up from the southern sea. The most common plants in this region are deciduous trees and shrubs, and the climate is warm, and exceedingly good for agriculture along the rivers that carry rainfall and snowmelt down from the surrounding mountains. But at the heart of this region, the geography shifts suddenly: in the distance, rising thousands of feet above the lowlands, great peaks are seen, their flanks shrouded in fog. These are not wooded slopes of isolated hills or volcanic remnants: these are living trees, the size of mountains.

The key to the history of this region, and to the nature of these immense forests, lies with the Dappese themselves. Sixty thousand years ago[1], the people of the Ammas Echor arrived in orbit of the planet and began their colonization efforts in what is now western Altuum. These were the first and the most significant group of Exiles to reach Sogant Raha early in its history, but not the only ones. More than ten thousand years later, a second vessel, called by its crew the Sanardur-nasandaburkant followed in the footsteps of the Ammas Echor; and what they found when they arrived disturbed them greatly.

[1] Taking, for the sake of convenience the Conn sacking of Presh as marking roughly the beginning of the “present era” of Sogant Raha, and using our measurement of the year rather than the local one.

The Sanda, as they called themselves at the time, were of a very different branch of the Exile than the Janese of the Echor. The ancestors of the Janese had sighted Sogant Raha long ago via the orbital transit method, which had shown them a world rich in water and oxygen, with many signs of an active biosphere, and they had reengineered their entire culture and their civilization in the hopes that their descendants would one day reach this world. In comparison, the Sanda were latecomers; their ancestors had detected planets around Kdjemmu (which they called Nakarriban) via the radial velocity method; the numerous small worlds around the star intruiged them, especially the one in the relatively clement circumstellar habitable zone, but they did not expect a world rich in liquid water and breathable air, and they certainly did not expect a world already peopled by humans.

The Sanardur-nasandaburkant was a small ship by the standards of the Exile, but a very technologically advanced one. Unlike the Janese, the ancestors of the Sanda had never lost the universal cell technology; indeed, they had been fortunate enough to occasionally invest time and energy in improving it, and improving their biotechnology generally. What they did not have, however, was a complete copy of the Great Record: an ancient schism had caused theirs to be lost to them, and compared to the millions of species of endobiota contained in the Ammas Echor’s Record, they had data on only a few thousand, much of which was incomplete. They had made much use of this information to hone their understanding of genetics and biology, and that expertise they had used to further adapt themselves to life in difficult environments–the Sanda were a hardy people, with a striking range of phenotypes very different from baseline humans, able to endure microgravity environments and radiation far better than baseline humans.

Only in the last years of their approach to Kdjemmu did the Sanda realize that the planet hosted a biosphere, a discovery as momentous to them as it had been to the Janese. In the course of the final breaking maneuvers used to enter orbit, it also became apparent that the Sandese were not the first humans to reach this world; and this information troubled them greatly. With their long memories, even if the earliest origins of mankind in Paradise were a hazy memory, that humanity in the Exile was a pale shadow of its former self. True, our species endured. On many worlds we even approached something like prosperity. Enough that, from time to time, some of those worlds could afford to build new ships, to crew them with new explorers, and to hope that somewhere out in the great darkness there could be a life less balanced on the precarious knife-edge of survival. But compared to the first few hundred thousand years of our species existence, in the lush springtime of of the world in which we were born, the amount of spare productive capacity that could be put to ends other than survival–that could be used for innovation, or creativity, or expansion–was paltry. So why, arriving at a planet as perfectly suited for human life as Paradise had been, did the Sanda find only silence?

Careful exploration of the surface was conducted; it was soon evident that some terrible catastrophe had befallen the first colonists on this world, and they had lost a great deal of the technological knowledge they had arrived with. The nature of this catastrophe was impossible to discern–it was wrongly conjectured to be linked to the layer of ash in the soil near the surface, a remnant of the Burning Spring, and to the ruins of the large concrete and steel cities that by this time dotted much of Altuum, Vinsamaren, and Démora. In fact, what the Sanda did not realize was that the catastrophe was not one, but many; and that they were ongoing. As they explored the surface, the dreaming planetmind observed them; and she was, insofar as we might analogize her experiences with our own, afraid--these were, after all, newcomers of the same kind that she had already judged a threat, and which had already radically changed her environment.

The initial plan of the Sanda was to maintain a presence in orbit, and to establish a small colony on the surface; they hoped to make contact with friendly locals, to build a small industrial base, and perhaps within a few centuries send a small vessel, with news of their discovery, back to their people. They succeeded only in partially accomplishing the first two of these goals; since the days of the first arrival of humans on the surface, some species of tahar had made major adaptations to living inside of the human body, and the first visitors of the surface brought it back to the ship. Within a few months, confusion, hallucination, and heightened aggression set in among the Sanda; their ship was sabotaged by crewmen who could later not explain why they did it, and they were forced to flee to the surface.

They brought with them enough of their technology to understand a little of their enemy, though; and they were able to genetically modified themselves to make their bodies less hospitable to the tahar. They also maintained much of their technological base long enough to adapt endobiota to create a protective habitat, one which could protect them from hostile invaders, and which would not require redeveloping an entire agricultural civilization overnight to keep from starving. This was the beginning of the great forests: chimeric strains of trees, mixing together cell lines from several distinct species, and borrowing many of the signalling mechanisms used by the tahar itself to regulate the resulting symbiotic relationship. At first, they were a source of food, of building materials, and of shelter; soon, though, the Sanda began to refine them further, and they became much more.

The native Dappese word for these organisms now is karuda, “mountain-tree;” and though a karuda may begin life as a sapling or a bulb, once fully-grown it is not much like its mundane cousin. Most woody endobiota rely on a system of xylem and phloem to move moisture and nutrients throughout their tissues; capillary action, transpirational pull, and the solute pressure of sugars in the phloem help to transport water from the roots to the leaves; hydrostatic pressure moves sugar-rich sap back down to nourish the tissues in the rest of the plant, all ultimately through a central trunk. In the karuda, the vascular system is much more complex; water and various nutrients are moved through as many as four different kinds of vascular tissue, which use active transport methods that can reach much higher pressures. As a result, where most trees on Earth could only slightly exceed a hundred meters or so in height, the karuda may be as much as three kilometers tall.

At that size, the upper foliage collects an enormous quantity of sunlight; much of the energy collected in this way is used to support the vascular tissue. A karuda is more akin to an immense colonial organism than a single plant; it has thousands of trunks which wind together and branch apart, creating an immense open lattice beneath its upper foliage. It is in these spaces that most of the Dappese, the descendants of the Sanda and neighboring peoples, now live; they can shape them with pruning and twisting methods to create living enclosures, to modulate the movement of air, and–on large scales–even to alter local weather patterns.

A karuda is as much an environmental engineering project as a habitat: they draw immense amounts of groundwater up into their branches, and the transpiration of water in the upper foliage creates masses of moist air, warmed by sunlight and the metabolic processes of the vascular tissue, that support immense hanging gardens. At the forest floor, so little light reaches the ground that it is nearly night-dark; here, the temperature is constant, and the air is mostly still. Where the warm air of the upper foliage and the cool air at ground level mix, there is a thick, turbulent fog layer; here, another layer of growth captures the moisture that condenses and what little light makes it down to this layer, and various arboreal animals thrive that the Dappese hunt for food.

The Dappese of later generations are not much like their Sanda ancestors. Culturally and linguistically, they are a fusion of the Sanda colonists and friendly peoples they allied with when they were forced to the surface; their language is in fact principally Sogantine, though with considerable Sanda influence–the prenasalized consonants of mbeki (“north”) and ngara (“south”) are reflexes of the Sanda nasal prefix, seen in both Nakarriban (na-karri-ban, “target star, star to which we are going”) and nasandaburkant (literally, “the vessel our people are traveling in”). Without the ability to produce the necessary technical equipment, the Dappese have lost the genetic engineering technology and machine construction capacity of their ancestors. But they have retained a long oral and written historical tradition, and they remain excellent astronomers and mathemeticians; alone of all the peoples of Sogant Raha, they have never forgotten that this is not their original home, and that humanity originated in the stars.

They are also physically distinct; although their exact appearance varies as it does in any human population, the prototypical phenotype of the Dappese is gray-skinned, with feet almost as good at grasping as hands, a great deal of flexibility, and the ability to easily adapted to a more rarefied atmosphere, such as that found at the summits of the karuda. About half of all Dappese have a second thumb instead of a fourth finger, a relic of ancient genetic modification.

Politically, the Dappese are only loosely affiliated; the region has proven inhospitable either to state-formation or the intrusion of surrounding polities. In the woodlands and forests, foraging, hunting, and light agriculture predominates; most inhabitants live in small villages, with larger trading towns forming a network of settlements that is important for the diffusion of technological and cultural innovations. Among the karuda, comparatively high population densities are possible, thanks to the large amount of vertical space and the possibility of layered horticulture. There are no large cities, but the whole volume of the karuda constitutes something like a vast townland, and the karuda-forests have a population of around eight or nine million.

A single karuda is often regarded as an economic and cultural unit; there are dialectical differences between karuda, and differences in custom and tradition. Governance, such as it is, is commonly based around village leaders or small councils, with matters concerning the whole tree sometimes requiring vast assemblies to negotiate. The stability of the environment, the lack of competition for resources, and the slower growth of karuda-adapted populations have tended to reduce the amount of large-scale conflict, although wars, both internal and external, are not unknown.

The most severe conflict which occurred in the history of the Dappese was in fact very recent: a generation ago, the nascent Conn empire sought to extend its dominion over southeastern Altuum. They made it all the way to the eastern coast, conquering numerous wealthy states in that region, but the Dappese forests presented a major barrier to expansion south, especially to the nearer parts of the Windlands. Initial forays using Conn cavalry into the forests were disasters; heavy infantry from the northeastern states, organized under Conn commanders, were more successful, but they had no useful tactics for penetrating the karuda, which the Dappese were far more capable of fighting in anyway.

The solution to continued resistance was simple: fire. By damaging the lowest levels of the karuda with oil-driven fires, the trees could be wounded, their upper layers could be deprived of water, and, as the wood dried, eventually the fire would spread to the upper levels. A series of unusually dry summers worked further in the favor of the Conn; within ten years, most of Dap Mbeki and large portions of Dap Ngara had been destroyed. One karuda was the work of dozens of generations of careful gardening; the Conn, in their hunger for conquest, destroyed thousands. Millions of Dappese died in the war; others fled south and west, trying to stay ahead of the rapidly expanding frontier of Conn conquest.

The consequences of this war were disastrous for the world as a whole. There was an immense loss of Dappese science and culture, of course; but the smoke plumes from the fires rose high into the stratosphere, and soon blanketed the world. The amount of ash released was equivalent to many Krakatoas, and it took decades to clear. The global temperature fell sharply, resulting in crop failures, famine, and disease; unknown to the Conn, this worked even further to their advantage. Famine and the resulting conflict in the west greatly weakened the states of Oethiam and Nebressa; Presh’s volume of trade declined, resulting in a small regional economic collapse. Twenty years later, when the Conn armies appeared on the horizon, there were few states positioned to resist them, and many princes were willing to turn on their neighbors in exchange for a favorable position in the post-conquest order.

Eventually, after the collapse of the Conn empire and the return of many Dappese refugees, the process of rebuilding the god-forests began; there has even been talk of planting new karuda to the east, to found a new forest: Dap Tassama, “the forest of rebirth.” It may be many centuries before the lands of the Dappese return to their former prosperity; but the Dappese are patient, and are already looking forward to a future that is even brighter than before.

12 notes

·

View notes