#before they were all emasculated by that terrible scurge of modern morality

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

[expect he has lost most of his shirt by now and some nice whip weals will add to charm of back view]

Blacklisted by Senator Joseph McCarthy for alleged "anti-American activities" and unable to work in Hollywood, Joseph Losey along with dozens of like-minded actors, directors, and creative personnel fled to Britain in the 1950s. Since before WWII, the trans-Atlantic relationship between the two entertainment industries had been a complicated one but in the prevailing climate of disintegration and consolidation, the influx of major (and minor) Hollywood talent was warmly welcomed. The Rank Organisation cultivated a reputation for going on indiscriminate spending sprees but invariably found itself having to release its expensive acquisitions for lack of meaningful employment.

Among the post-war Rank recruits, content creators were the exception, and this affected the quality, if not the quantity, of the Organisation's cinematic output. When Joseph Losey finally did receive his first assignment, to direct The Gypsy and the Gentleman, it bore the hallmarks of a case in point: no records have as yet emerged that would explain the somewhat eccentric choice, for the politically left-leaning Losey, of a lavish costume piece about the demise of a weak-willed nobleman at the hands of his ruthless gypsy lover - unless one is inclined to see in the material a parable of Western decadence, as Marxist observers have done.

While a strictly ideological interpretation produces interesting speculative conclusions, perhaps the more productive approach is a purely visual one: dismissive of the subject-matter and unable to shape the material to his liking, Losey never attempts to explain his characters or their motivations. The result is a very deliberate focus on the process of telling the story rather than why it is being told, and Losey turns to the expertise of the painter and art school teacher Richard MacDonald to direct what he would later describe as a study in style. Losey and MacDonald subsequently collaborated on a number of films but it is in the development of The Gypsy and the Gentleman that their idea of "pre-design" begins to emerge.

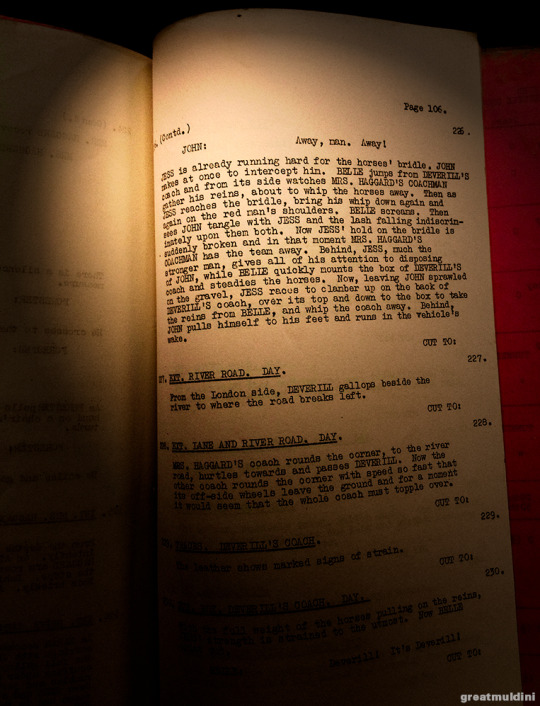

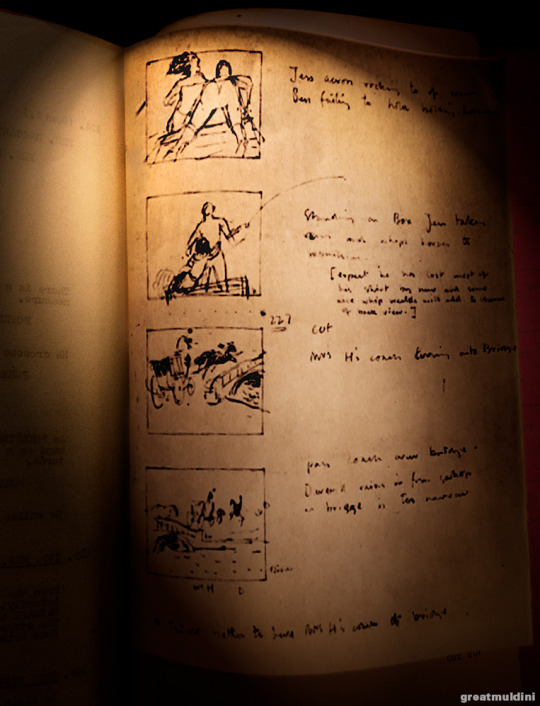

And concrete shapes are Richard MacDonald's primary concern: long before the cast arrived for initial rehearsals in June of 1957, MacDonald was creating actual three-dimensional spaces (rather than trompe-l'oeil, i.e. painted, theatrical backdrops) for a quasi-authentic Regency environment. Faithfully executed by the Pinewood workshops, the sets delivered exactly what the director had ordered: a static tableau of period décor, unlikely to interfere with the dynamic action of the living, breathing human beings assembled to animate the scenery. Ideally, it would have been assumed, they would somehow combine to form a meaningful whole. The dynamism of the human component and the critical role of capturing the perfect - moving - image is not lost on MacDonald. From the final shooting script of 12 April 1957 he prepared a frame-by-frame storyboard pre-visualizing camera angles, editing suggestions and emendations where the script omits important visual clues.

The final dramatic coach chase in SCENE 226 lacks precisely such clues. It has Jess and Belle racing after the vehicle containing Deverill's sister Sarah - and their last hope of swindling the young woman out of her rightful inheritance. Jess deftly dispatches Sarah's fiancé before catching up to Belle's commandeered coach. The script describes how Jess clings to the back of the coach, then climbs over the top and joins his partner on the box, taking the reins from her. Translating the verbal instructions into "actionable" images, the sketch artist is faced with crucial choices: whose point of view will we be sharing, where are we in relation to the characters, what are the characters doing and how are they doing it?

In MacDonald's concept the camera follows the coach and allows us to watch Jess, from a slightly elevated vantage point and at a medium distance, which frames his figure framed atop the speeding coach. His technique, crouched low on his stomach, and the fact that he is moving with a natural ease and grace suggests he has done this before: Jess knows what he must do to get what he wants. The "savage" man's essential virility (in stark contrast to Deverill's effete decadence) is sketched out by MacDonald in a few sparse pen strokes not of his face but of his obviously well-endowed body in the act of taking control. We do not need, indeed it would be beside the point, to read his face for signs of physical strength and determination, which are required in the situation and which Jess does have in abundance.

MacDonald would have drawn his inspiration from the characterizations of Jess throughout the script, but he goes above and beyond the written word where continuity is less than assured and actions must and will have visible consequences. Following the coach man's ferocious use of the whip against his attacker, MacDonald's instinct is to zoom in on the gory details - with a flair for unflinching hyper-realism only the true aficionado would have appreciated had the sequence been filmed as planned. Unfortunately for the aficionado, in the finished film the coach man no longer wields his whip, and the only drastic imagery we are being exposed to is the crude back projection footage that has taken the place of MacDonald's charming back view proposal. Ultimately, of course, only those images that make the transition from sketchbook to screen will live to tell the tale.

Making those life-and-death decisions is the director's prerogative; his omnipotence however does not extend beyond the telling of the tale: Joseph Losey does not choose his fictional characters, nor does he decide what happens to them. His selection criteria are practical rather than ideological, aesthetic rather than commercial - or they would have been, in an ideal (fictional) world. The bold proposals of his draughtsman may have presented Losey with a variety of stubborn obstacles, but an equally plausible explanation for the use of conventional studio footage in place of the more experimental tracking shot could be post-production objections to the pre-designed perspective. Scenes could have been rewritten and re-enacted at the behest of unhappy Rank executives, to add close-up shots of the actors' bankable faces amid the racing carriages.

Beyond the promise of commercial appeal it is an intriguing question to ponder whether the studio inserts offer valid or even valuable alternatives to the aesthetic aspirations of MacDonald's narrative. In the end, the project proves its own premise: art may exist for art's sake but no such claim has ever been made for style. As a medium in search of its message, Joseph Losey's visual and perhaps visionary experiment remains strangely incomplete, a promise unfulfilled.

#Patrick McGoohan#Melina Mercouri#Lyndon Brook#The Gypsy and the Gentleman#Jess I'm sure knows all there is to know#about unfulfilled promises#being such a virile specimen of the species#the script rather mysteriously is brimming with#references to his manly deeds and demeanour#but we never get close enough to take a sample for ourselves#that said noone gets close to Jess which suits him just fine as he goes#through the film entirely unaffected by anything that happens#Jess is the ultimate embodiment of healthy#unencumbered self-determination#or as we would call it toxic masculinity#although contemporary commentators preferred a different term#virility is such a strange word isn't it#cringe-inducing these days it used to be the defining quality of heroic men#before they were all emasculated by that terrible scurge of modern morality#the permissive society#and that is why heroic Jess is probably still camping out in the woods somewhere#I know he is#Ohhhhh Jess

16 notes

·

View notes