#been thinking a lot lately of how a father's profession influences the thinker

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Louise Glück, NYT

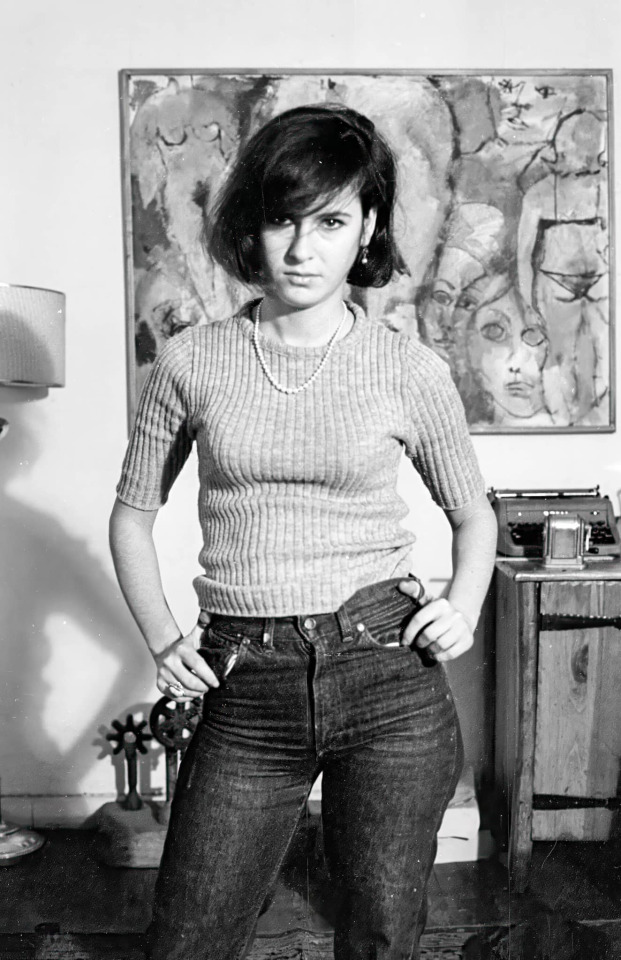

Louise Glück, photo by Charles S. Hertz

b. 1943

The Nobel-winning poet was pitiless to herself, yet fiercely generous toward her students.

By Amy X. Wang The New York Times

She stood barely five feet tall — slight, unassuming, you had to stoop low to kiss her cheek — but whenever Louise Glück stepped into a classroom, she shot a current through it. Students stiffened their spines, though what they feared was not wrath but her searing rigor: Even in her late 70s, after she won the Pulitzer and the National Humanities Medal and the Nobel, she always spoke to young writers with complete seriousness, as if they were her equals. “My first poem, she ripped apart,” says Sun Paik, who took Glück’s poetry class as a Stanford undergraduate. “She’s the first person whom I ever received such a brutal critique from.” Mark Doty, a National Book Award-winning poet who studied under Glück in the 1970s at Goddard College, felt that she “represented total authenticity and complete honesty.” This, he recalls, “pretty much scared me half to death.”

Spare, merciless, laser-precise: Glück’s signature style as a writer. It was there from an early age. Born in 1943 to a New York family of tactile pragmatists (her father helped invent the X-Acto knife), Glück, a preternaturally self-competitive child, was constantly trying to whittle away at her own perceived shortcomings. When she was a teenager, she developed anorexia — that pulverizing, paradoxical battle with both helplessness and self-control — and dropped to 75 pounds at 16. The disorder prevented her from completing a college degree. Many of the poems Glück wrote in her early 20s flog her own obsessions with, and failures in, control and exactitude. Her narrators are habitués of a kind of limitless wanting; her language, a study in ruthless austerity. (A piano-wire-taut line tucked in her 1968 debut, “Firstborn”: “Today my meatman turns his trained knife/On veal, your favorite. I pay with my life.”) In her late 20s, Glück grew frustrated with writing and was prepared to renounce it entirely.

So she took, in 1971, a teaching job at Goddard College. To her astonishment, being a teacher unwrapped the world — it bloomed anew with possibility. “The minute I started teaching — the minute I had obligations in the world — I started to write again,” Glück would confess in a 2014 interview. Working with young minds quickly became a sort of nourishment. “She was profoundly interested in people,” says Anita Sokolsky, a friend and colleague from Williams College, where Glück began teaching in 1984. “She had a vivid and unstinting interest in others’ lives that teaching helped focus for her. Teaching was very generative to her writing, but it was also a kind of counter to the intensity and isolation of her writing.”

Glück’s own poems became funnier and more colloquial, marrying the control she earlier perfected with a new, unexpected levity (in her 1996 poem “Parable of the Hostages”: “What if war/is just a male version of dressing up”), and it is her later books, like the lauded “The Wild Iris” from 1992, that made her a landmark literary figure. Teaching also coaxed out a new facet in Glück herself: that of a devoutly unselfish mentor, a tutor of unbridled kindness.

A less fastidious writer and thinker may have made their teaching duties rote — proffering uniformly encouraging feedback or reheating a syllabus year after year. Glück, though, threw herself into guiding pupils with the same care and intimacy she gave to her own verses. “There was just this voraciousness, this generosity,” says Sally Ball, who met Glück while studying with her at Williams and remained close with her for the three decades until her death. “Every time I moved, she put me in touch with people in that new place. She enjoyed bringing people to know each other and sharing the things she loved.” And as a teacher, Ball says, “Louise was really clear that you have to make yourself change. You can’t just keep doing the same things over and over again.” In that spirit of boundless self-advancement, Glück also taught herself to love cooking and eating. She once hand-annotated a Marcella Hazan recipe and mailed it to Ball, with sprawling commentary on how best to prepare rosemary. “She’s very beautiful and elegant, right,” Ball says, but “we’d go to Chez Panisse and sit down and she eats with gusto. It’s messy, she’s mopping her hands around on the plate.”

Paik recalls spending hours each week decoding Glück’s dense, cursive comments on her work. “I was 19 or 20,” she says, “writing these scrappy, honestly pretty bad poems, and to have them be received with such care and detail — it pushed me to become a better writer because it set a standard of respect.”

“She was 78, and whenever she talked about poetry, it felt like the first time she’d encountered poetry,” says Shangyang Fang, who met Glück when he was at Stanford on a writing fellowship. Glück offered to edit his first poetry collection, and the pair became close friends. “She would talk about a single word in my poem for 10 minutes with me,” Fang says. Evenings would go late. They cooked for each other sometimes, spending hours talking vegetables and spices, poetry and idle gossip. “By the end, I couldn’t thank her enough, and she said: ‘Stop thanking me! I am a predator, feeding on your brain!’”

#predator#louise glück#nyt#goddard#marcella hazan#chez panisse#Shangyang Fang#x-acto#i am a predator#feeding on your brain#poetry#anorexia#been thinking a lot lately of how a father's profession influences the thinker

11 notes

·

View notes