#ayaan can you do that voice again for us

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Section 1: Under the Serviceberry Tree

The afternoon sun draped its golden light over the meadow, filtering through the leaves of the serviceberry tree. Leila sat with her back pressed against the rough bark, fingers tracing its grooves as if reading a story. The tree stood as it always had—weathered but strong, with roots knuckling deep into the earth, steady and unchanged. Her gaze wandered across the land, lingering on the edges where wild grasses swayed and small animals darted between shadows.

This tree had watched generations of her family come and go, their lives folding into the earth beneath its roots. It was a symbol of everything she cherished about this land, and it reminded her that the roots of her ancestors still ran through this soil. She closed her eyes, breathing in the scent of earth and sun-warmed leaves, letting herself feel anchored, even as the world around her threatened to shift and scatter.

Footsteps crunched softly on the dry grass, drawing her attention. Ayaan, her cousin, approached with his hands tucked into his jacket pockets, shoulders slightly hunched. He looked out of place here, like he’d brought a piece of the city with him. She could see the restless energy in his stride, a pace that was at odds with the tree’s quiet endurance.

Ayaan came to a stop beside her, his gaze drifting over the field. “You ever wonder what it was like before?” he murmured, as if the land itself were listening.

Leila looked up at him, eyebrows raised. “What do you mean?”

He kicked a small stone, sending it skittering across the ground. “Before all this,” he gestured vaguely toward the horizon where the faint outlines of buildings were visible. “When this was all forest.”

Leila let her fingers linger on the bark, her voice soft. “It wasn’t just forest, Ayaan. It was a whole world, a web of life—everything bound together, each creature playing a role.” She traced a crack in the bark, her fingers catching on a piece that flaked off. “We knew how to live within it, how to take just enough and give back.”

Ayaan shifted his weight, looking uncomfortable. “But that’s not how things work now,” he said, glancing away. “People need homes, jobs. They call it progress for a reason.”

“Progress,” she echoed bitterly, pulling her hand back from the tree. “It’s a kind of rot. We take and take without thought for what we leave behind. This tree,” she gestured to the serviceberry, “it gives to the land, feeds the animals, shelters birds. We used to live like that, part of the cycle. Now we’ve turned into something different… something invasive.”

Ayaan sighed, glancing down. “Not everyone feels that way, Leila. And it’s not like we can just go back. Things are different now.”

A soft rustling interrupted them, and they turned to see Amara, the village elder, approaching. Her steps were slow and steady, each one a testament to the years she had walked this land. Her silver hair caught the light, and her face, lined with age, carried a gentle wisdom that seemed to flow from the earth itself.

She stopped beside them, her gaze following the line of the horizon. “You’re both right,” she said, her voice calm but weighted. “Going back isn’t the answer. But moving forward without memory… that’s like planting a seed in poisoned soil.”

Leila looked up at Amara, her eyes filled with questions. “Do you think it’s too late, Amara? Have we taken too much?”

Amara’s eyes softened, and she shook her head. “It’s not too late, child. But the choices we make now will decide everything. Every step we take matters. We can continue as we have, consuming without care, or we can learn again what it means to be rooted.”

Ayaan ran a hand through his hair, looking uneasy. “I get what you’re saying, but… how? How do we even start to fix something so broken?”

Amara’s gaze turned toward the tree. “By remembering what we’ve forgotten,” she said, her voice barely above a whisper. “By listening to the land, by watching how it endures, how it gives and takes in balance. The serviceberry doesn’t hoard its fruit; it gives freely. It offers what it can and then rests, knowing the cycle will continue. But we…” She trailed off, her face creased with sorrow. “We’ve lost that trust in the cycle.”

Leila looked at the tree, feeling a pang of something deep and old, as if she were connected not just to her ancestors but to something even older. She could feel the weight of Amara’s words settling over her, like the shade of the tree itself.

Ayaan’s voice cut through the quiet. “But that’s just nature, right? It’s not the same for us. We have needs, goals, ambitions. We can’t just live like trees.”

Amara turned to him, her eyes sharp. “And what has that thinking brought us, Ayaan? Look around. We’ve taken and taken, until the earth bleeds beneath our feet. We’ve consumed beyond our needs, beyond what this land can bear. What do you think will happen when there’s nothing left to take?”

Ayaan was silent, his eyes fixed on the ground. Leila could see the conflict in his face, the tug between the world he’d been raised in and the truth that lay beneath Amara’s words.

Amara’s voice softened. “I don’t say this to shame you, Ayaan. I understand the pressures of this world, the demands it places on each of us. But if we forget the wisdom of the land, if we forget how to live within its cycles, then we are lost.”

Leila looked from Ayaan to Amara, feeling a growing determination. “So what do we do, Amara? How do we start to make things right?”

Amara placed a hand on the tree, her fingers tracing its bark as if in communion. “We begin by grounding ourselves. By remembering our place within this world. Each choice we make ripples outward. Every time we choose to take only what we need, to give back what we can, we begin to heal the rot within our roots.”

Ayaan sighed, his shoulders slumping slightly. “It sounds… idealistic. People don’t think like that. They don’t care about trees or roots. They just want to get by, to survive.”

Amara looked at him, her gaze unwavering. “Survival is not conquest, Ayaan. It is not a race to take more than the next person. True survival is a collaboration. It is learning to live as the land lives, to find strength in balance. If we do not learn this, then survival will become an illusion.”

Leila’s fingers tightened around a small piece of bark in her hand. She understood the weight of Amara’s words, the challenge they represented. But for the first time, she felt a spark of hope—fragile but real. They could start here, in this moment, beneath the serviceberry tree, remembering what it meant to be connected, to be rooted. The path ahead would not be easy, but it was a path she was willing to walk, and she hoped Ayaan would join her.

As the sun began to sink behind the hills, casting the meadow in a warm, golden glow, Leila felt a shift within herself, a small but steady resolve. They might be small in the grand scheme of things, but perhaps, just perhaps, they could begin to heal the rot that had spread through their roots.

Section 2: American Jesus

American Jesus strode down the gray streets, his form draped in the symbols of modern worship: immaculate suits, designer shoes, a watch that cost more than most could afford in a year. His face was smooth, ageless, flawless—crafted to perfection as if sculpted by the very hands of capitalism itself. His smile was broad, polished, and without substance, promising everything yet offering nothing.

To his followers, he was a beacon of progress. To those who struggled beneath his shadow, he was an inescapable presence—an empire personified, the golden calf of a modern world. He moved with the quiet authority of someone who knew the world was his to claim, and each step left the faintest trail of ash and dust in his wake.

A group of young professionals watched him pass, their eyes glazed with awe and envy. “There goes American Jesus,” one of them whispered, his voice laced with reverence. “If only we could reach his level.”

Another nodded, her voice trembling with ambition. “He’s proof that we can make it too, if we just work hard enough, sacrifice enough.” But her hands were rough, chafed from long hours at a job that seemed to demand pieces of her soul in exchange for a paycheck.

From a distance, in the shadows cast by steel skyscrapers, an old man watched American Jesus with weary eyes. He’d seen empires rise and fall, witnessed the ebb and flow of fortunes. He knew the cost of the smile American Jesus wore—the emptiness that lay behind it. As American Jesus disappeared around a corner, the old man murmured to himself, “Every god has its price.”

Not far away, within the confines of a glossy high-rise office, Marcy sat alone in her cubicle, staring blankly at the screen. She was thirty-five but felt much older, worn thin by a life of constant striving. Her desk was littered with motivational quotes: “Hustle Hard,” “Success is Earned, Not Given.” Each one a mantra she had clung to like a life raft, even as her days grew emptier, hollowed by the demands of a job that seemed to siphon off parts of her spirit.

Her phone buzzed with a message from her mother. Have you had dinner yet? Remember to take care of yourself.

Marcy ignored it. She didn’t have time to eat, didn’t have time to think. There was only the grind, only the endless demands that had become her reality. She glanced at a calendar pinned beside her desk, each day marked by deadlines and meetings. She had no memory of the last time she’d looked forward to anything, the last time she’d felt something other than exhaustion.

She looked out the window, catching a glimpse of American Jesus as he walked by, surrounded by admirers. She felt a pang of something—admiration mixed with envy, a yearning that she didn’t fully understand. She, too, wanted to stand in the light of success, to be seen as something more than a cog in the machine. But deep down, she knew that even if she reached his level, it would be hollow. She was already seeing the cracks in the golden idol.

The screen saver on her computer flickered, flashing images of serene landscapes, mountains, forests—places untouched by the clutches of corporate power. She felt a tug at her chest, a faint longing for something she couldn’t quite name. She wondered if there was more to life than this constant climb, this endless cycle of production and consumption. But the thought was quickly dismissed. This is the way of the world, she reminded herself, echoing the words of her mentors. If you’re not moving up, you’re falling behind.

As night fell, Marcy finally left her desk, her feet dragging as she stepped onto the cold, empty street. American Jesus was gone, but his presence lingered, etched into the walls, the billboards, the very air. She could feel it, pressing down on her, a weight that had become so familiar she no longer questioned it.

Across town, at a bustling nightclub filled with strobe lights and pounding music, others sought refuge from their own empty routines. The air was thick with smoke and perfume, a haze of artificial pleasure masking the loneliness that pulsed beneath the surface. This was a temple of sorts, a place where people came to worship distraction, to numb themselves from the relentless demands of the world outside.

Marcus leaned against the bar, nursing a drink, his eyes scanning the crowd. He was well-dressed, successful by every outward standard, but his gaze was distant, unfocused. He felt adrift, like he was moving through life in a fog. He’d achieved everything he’d been told would make him happy—the job, the car, the house. Yet none of it filled the void gnawing at him.

Beside him, a woman laughed too loudly, her smile strained, her eyes searching for something she couldn’t quite name. “Isn’t this place amazing?” she shouted over the music, her voice laced with forced enthusiasm. But Marcus could see the truth in her eyes—she, too, was just another pilgrim in search of meaning, grasping for connection in a sea of strangers.

As the night wore on, the crowd grew restless, their movements increasingly frenetic, their laughter more brittle. They were dancing, drinking, clinging to the fleeting promise of joy, but beneath the surface lay the same hollowness that shadowed Marcy, that clung to every corner of the city.

American Jesus loomed over them all, an invisible hand guiding their desires, their fears. He was the architect of this world, the embodiment of everything they’d been taught to worship—success, power, the relentless pursuit of more. But his blessings were curses in disguise, plagues that seeped into their souls and left them yearning for something they couldn’t find.

Isolation crept into their lives like a shadow, a quiet plague that took root in the spaces between them. Despair followed close behind, filling the void with a sense of helplessness, a feeling that nothing they did would ever be enough. Environmental Collapse loomed on the horizon, the earth itself groaning under the weight of their greed. And all the while, Addiction, Illusion, Mental Illness, and Disillusionment thrived, feeding on their discontent.

In the early hours of the morning, when the streets were empty and the city lay silent, American Jesus stood on the rooftop of a gleaming skyscraper, looking out over his domain. His smile was unchanging, a perfect mask that hid the rot beneath. He was the golden idol, the false savior, the promise of a better life that never came. And he knew that as long as they worshiped him, as long as they believed in the dream he sold, they would remain bound to him, unable to break free.

But somewhere, deep within the city, a faint stir of resistance began to grow. It was small, barely noticeable, like a seed buried in the earth, waiting for the right moment to break through. It was a spark, a glimmer of hope that had not yet been extinguished.

And as the first light of dawn touched the skyline, that spark flickered, refusing to be snuffed out. It was a reminder that even in the face of American Jesus and his plagues, there was still a chance for something different—a chance to remember, to reclaim, to break free from the chains of a world built on hollow promises.

Section 3: The Plagues

The first was Isolation. It seeped into lives quietly, disguised as progress. People moved into high-rise apartments with thick walls, their windows gazing out over landscapes they never touched. Social media buzzed with notifications and “likes” but left a hollowness afterward—a digital approximation of connection that paled next to the real thing.

Darren, a software engineer, felt this keenly. Most of his friendships were through screens, interactions distilled to quick texts and emoji reactions. He hadn’t touched another person in days, maybe weeks; even his job was remote, his voice just another filtered note over a virtual meeting. When he went to the grocery store, he was almost afraid to meet people’s eyes, the muscle memory of small talk eroded by endless scrolling. He was surrounded, yet he was profoundly alone. And he was far from the only one.

Isolation wasn’t a plague that struck all at once—it crept into the cracks, filling the empty spaces until it became the baseline of existence. Its effects were subtle yet devastating, an unspoken epidemic that left people separated even when they were close. The streets were full of people, but they walked past each other like ghosts, each lost in their own world.

Then there was Despair. The more isolated people became, the deeper this plague took root. With each passing day, the weight grew heavier, a slow erosion of hope. Despair turned into a collective numbness—a pervasive feeling that life was a treadmill going nowhere.

Nina, an elementary school teacher, had once been full of passion, determined to make a difference in her students’ lives. But years of standardized testing, budget cuts, and overcrowded classrooms had taken their toll. She began to feel like a cog in a machine, her work reduced to metrics and performance reviews. The light in her eyes dulled, and her voice lost its warmth. She felt trapped, unable to quit yet unable to stay. Despair was there, lingering in the background, whispering that things would never change.

As despair took hold, so did Environmental Collapse. The world outside began to reflect the turmoil within, the earth itself mirroring humanity’s inner chaos. Rivers ran dry, forests turned to ash, and cities swelled with pollution, the air thick and unbreathable.

Theo, an environmental scientist, spent his days studying charts and models, each one forecasting a grimmer future. He used to go hiking every weekend, but now he avoided the trails—seeing once-green landscapes reduced to dust only intensified his own sense of powerlessness. He’d given up on trying to explain the urgency of change to those around him; people either shrugged it off or dismissed him as a doomsayer. And so, he watched in silence as the world crumbled, knowing he was powerless to stop it.

Addiction came next, filling the void left by despair and isolation. People turned to substances, screens, and shopping, anything to numb the emptiness they felt inside. Dopamine became the new currency, and addiction was its most reliable supplier.

Jesse, a marketing executive, was hooked—not on drugs, but on his phone. He couldn’t go more than a few minutes without checking it, his mind craving the next hit of validation, the next notification. He was a slave to the pings and dings, his sense of self-worth wrapped up in the number of likes he received. The real world grew less vibrant, its colors muted compared to the glow of his screen. And every moment spent scrolling took him further away from himself, deeper into the grip of addiction.

Illusion soon followed, feeding on the artificial images projected by screens and advertisements. People were bombarded with images of perfection—perfect lives, perfect bodies, perfect relationships. The world was painted in a gloss that covered up the cracks, an illusion that promised happiness just one purchase, one promotion, one relationship away.

Emily, an influencer, lived her life in front of a camera. She was the embodiment of illusion, her every moment carefully curated and filtered for her followers. But the reality was different. Her apartment was small, cluttered, her relationships strained. She spent hours editing each photo, erasing the blemishes, making her life appear effortless. She was trapped in the image she had created, a prisoner of her own facade. Illusion had wrapped itself around her life, leaving her unable to tell where the mask ended and the person began.

As illusion took hold, Mental Illness surged. Anxiety, depression, and burnout became the norm rather than the exception. People began to buckle under the weight of expectation, their minds frayed by a constant barrage of pressure and fear.

Rita, a college student, felt this acutely. She was expected to excel in her studies, maintain a social life, volunteer, and plan her career—all while managing her mental health. The pressure was relentless, the standards impossible. She began to experience panic attacks, her mind racing with thoughts she couldn’t control. She tried to keep up, but each day felt like a battle, her energy drained by the demands placed upon her. Mental illness had wrapped itself around her like a vine, squeezing tighter with each passing moment.

Finally, there was Disillusionment. It settled over society like a fog, blurring the lines between truth and lies, reality and fiction. People began to lose faith—not just in systems or leaders, but in each other. Trust eroded, cynicism flourished, and the collective spirit grew brittle and cold.

Oliver, once an activist, had been disillusioned by years of fighting battles that never seemed to yield real change. He’d believed in people’s ability to come together, to work toward a better world. But the more he saw, the more he realized that change was elusive, tangled in red tape and vested interests. He watched as movements splintered, as allies became adversaries. Disillusionment settled in his bones, leaving him weary, doubtful that anything he did could make a difference.

Each plague fed into the next, creating a vicious cycle that bound people tighter to the world American Jesus had built. Isolation fueled despair; despair left people vulnerable to addiction; addiction fed illusion; illusion masked mental illness; mental illness fostered disillusionment. And as each person succumbed, the world grew darker, colder, a place where connection and hope were nothing more than distant memories.

But amidst the darkness, the faint stirrings of resistance continued. A small group began to see through the illusion, to recognize the plagues for what they were. They gathered in quiet spaces, sharing stories, reclaiming their humanity piece by piece. They knew it would be a long journey, that the road to freedom was fraught with difficulty. But they also knew that the chains binding them were not unbreakable.

The plagues may have been pervasive, woven into the fabric of society, but they were not all-powerful. The spark of resistance glowed brighter, fueled by the recognition that they were not alone, that they could still find meaning, connection, and hope in a world bent on taking it from them. And in that shared struggle, a new path began to emerge—a path that led away from American Jesus and his empire, toward something truer, something real.

Section 4: Breaking Free

In the shadow of American Jesus and his empire, resistance took root like weeds breaking through cracks in the concrete. It wasn’t a grand, orchestrated movement; it was quiet, almost imperceptible at first—a whisper passed between people who were exhausted from the illusion, the addiction, the isolation. Each whisper was a question, a doubt, a desire for something different, something real. Breaking free began not with revolution but with a subtle shift in perception, a realization that the walls keeping people captive were largely self-imposed.

The path toward liberation was not straightforward. There was no map, no instructions. Each person had to carve their way through the fog of disillusionment, often stumbling, often feeling alone. But each stumble was a step, and with each step, the illusion began to thin, revealing glimpses of what lay beyond.

The journey of breaking free began with Recognition—seeing the plagues not as isolated misfortunes but as symptoms of a larger system designed to drain, distract, and control. Recognition was an awakening, a new understanding that one’s despair, loneliness, and frustration weren’t personal failings but manufactured states, maintained by forces that profited from their suffering.

For Jasmine, recognition came after she read an article about how social media platforms were designed to be addictive. She had always blamed herself for her inability to put her phone down, for her dependence on the dopamine hit of likes and comments. But as she learned more, she realized her addiction was engineered. She felt a mix of anger and relief—anger at the system that had exploited her vulnerabilities, relief at knowing she wasn’t alone in her struggle. Recognition planted a seed in her mind: what if she could reclaim her attention, her energy? What if she could find satisfaction in something real, something tangible?

Recognition was only the first step. As people woke up to the forces shaping their lives, they began to search for ways to reclaim what had been taken. This led to the next phase: Reconnection. Reconnection was about returning to what was real, to the people, places, and practices that grounded them. It was about cultivating relationships that weren’t mediated by screens, finding joy in activities that didn’t involve consumption, and experiencing moments of stillness in a world constantly demanding movement.

Reconnection required courage. In a society that valued productivity over presence, slowing down felt like rebellion. Hannah, a corporate lawyer, took her first real step toward reconnection by unplugging from work on weekends. It was difficult at first; her phone itched in her pocket, and her mind raced with worry about missed emails. But gradually, she began to feel the relief of not being tethered to a constant stream of demands. She spent time with her partner, took long walks, read books—not to post about them but simply to enjoy them. Through reconnection, Hannah felt a wholeness she hadn’t experienced in years, a sense of belonging to herself rather than to a company or a screen.

From reconnection emerged Reclamation. As people began to reclaim parts of their lives from the grips of technology and consumerism, they found a newfound power in saying “no” to the demands of American Jesus. Reclamation was about setting boundaries, about defining what one was willing to give and what they refused to sacrifice.

Reclamation required a rethinking of values. Eric, a college professor, realized that his worth was not tied to his productivity. For years, he had pushed himself to publish papers, take on extra students, and attend conferences, driven by a sense of obligation. But now, he began to question who he was really serving. He scaled back his commitments, chose to invest more in his students rather than in accolades, and rediscovered a love for teaching that he’d lost somewhere along the way. Reclamation, for Eric, was a rejection of the constant need to prove himself and an embrace of his own value, independent of external validation.

As people reclaimed their lives, they began to recognize a shared struggle—a commonality in their desire to escape the empire of American Jesus. This sense of solidarity led to the next phase: Community Building. Breaking free, they realized, was not an individual journey. To sustain their liberation, they needed each other. Community building was about finding others on the same path, people who understood the difficulty of letting go of the illusion and were willing to support each other in the journey toward freedom.

Community building wasn’t easy. The instinct to isolate was strong; trust had been eroded by years of competition, suspicion, and judgment. But slowly, communities began to form. Some were small and intimate, groups of friends meeting in each other’s homes. Others were larger, organized around shared interests or goals. There were book clubs, urban gardens, art collectives, and support groups. Each one was a space where people could be themselves without fear of judgment, where they could express their doubts, fears, and hopes in a way that felt honest and safe.

Sophie, an artist, found her community in a local makers’ market. She had been selling her art online for years, her interactions limited to comments and messages. But at the market, she was able to speak with people face-to-face, to share the stories behind her work. She met other artists, each with their own journey of breaking free, and found herself part of a network of creators who valued art as expression rather than commodity. Her community gave her strength, reminding her that she wasn’t alone, that there were others striving to create a world outside the control of American Jesus.

Through these communities, the final phase of breaking free began to unfold: Resistance. Resistance was the collective action taken to dismantle the systems that perpetuated the plagues. It was about more than just surviving; it was about creating spaces where people could thrive, where they could live in alignment with their values rather than the demands of capitalism and corporate greed.

Resistance took many forms. Some people organized protests, others started cooperatives, while others worked to create alternative systems of support and care. Each act of resistance was a defiance of the narrative that people were powerless, that they had no choice but to submit to the status quo. Resistance was the embodiment of hope, a declaration that a different world was possible.

For many, resistance was about reclaiming autonomy over their own lives. Communities formed to support mental health outside of profit-driven industries; farmers markets sprang up in food deserts, bringing fresh produce to communities long denied it; worker cooperatives allowed people to share in the fruits of their labor rather than serving as disposable cogs. Each act of resistance was a step toward dismantling the empire of American Jesus, a brick removed from the walls that kept people captive.

Breaking free wasn’t an end but a beginning, a continuous process of unlearning, reconnecting, and resisting. It was a reminder that freedom wasn’t something granted by an outside force but something cultivated within, a choice to live with integrity, compassion, and purpose in a world that often seemed intent on stripping those things away.

In this collective journey, the empire of American Jesus began to tremble. It was slow, almost imperceptible, but change was happening. The system depended on people’s isolation, their despair, their willingness to submit. And as more and more people chose to break free, to support each other, to resist, the foundation of American Jesus’s empire began to crack.

The journey toward liberation was arduous, filled with setbacks and doubt, but it was also filled with moments of joy, connection, and meaning. Each person who broke free became a beacon for others, a reminder that the chains binding them were not unbreakable. And as the plagues lost their grip, as the illusion faded, a new vision began to emerge—a vision of a world where people lived not for profit, not for power, but for each other, for the earth, for the simple, profound beauty of being alive.

Section 5: A New Covenant

As the empire of American Jesus began to weaken under the collective weight of resistance, there was a growing call for something more—a new covenant, a shared commitment to values that transcended profit, productivity, and power. This new covenant was not about forming another rigid system, but about creating a framework for living rooted in respect, cooperation, and care. It was a shift from individualism to interdependence, from extraction to reciprocity.

The covenant took shape through Principles of Mutual Responsibility. People began to recognize that survival and thriving could not be separated; one person’s wellbeing was linked to the wellbeing of all. Instead of focusing solely on individual success, they committed to uplift each other, understanding that collective flourishing was the only sustainable path. This was not a vague ideal but a set of actionable steps to ensure that every person’s basic needs were met. Housing, healthcare, education, and food were not luxuries or privileges; they were recognized as rights, and communities organized around the shared goal of ensuring these essentials for all.

For some, mutual responsibility began with something as simple as neighborhood food sharing. People set up free fridges, stocked by the community for anyone in need. Gardens grew in abandoned lots, tended by those who had never worked the soil before, producing fresh food in neighborhoods that had once been food deserts. In place of charity, which often created dependency, there was a new ethic of Shared Stewardship. People didn’t just give; they worked together, breaking down the barrier between those who have and those who need.

This shift toward mutual responsibility called for a second principle: Ecological Harmony. Recognizing that the plagues of environmental collapse and despair were interconnected, people began to reimagine their relationship with the land, not as something to be dominated, but as a partner in sustaining life. Practices of sustainable agriculture, conservation, and ecological restoration replaced the extractive practices that had devastated the earth. Communities moved away from disposable culture, choosing instead to live with less, to mend and reuse, to cultivate a mindset of sufficiency rather than excess.

Ecological harmony wasn’t about returning to some idyllic past; it was about learning to live in balance, to make choices that considered the needs of future generations. This required profound humility—a recognition that humans were not at the center of the universe but part of a vast, interconnected web of life. For those like Maya, a former tech executive who left her high-paying job to become an environmental educator, this meant more than planting trees or reducing waste. It was about fostering a sense of wonder and respect for the natural world in the next generation, so that the mistakes of the past would not be repeated.

The third principle of the new covenant was Transparent Governance. The era of American Jesus had been defined by secrecy, manipulation, and control, with decisions made in boardrooms and government offices without input from the people whose lives they affected. In contrast, transparent governance meant that power was distributed rather than concentrated. Decisions were made in public forums, with accountability mechanisms to prevent corruption and abuse. Leadership was not about accumulating power but about serving the community, with leaders chosen for their integrity and commitment to the collective good.

Transparent governance took many forms, from neighborhood councils to larger cooperative networks. People were invited to participate, to have a say in the decisions that affected their lives. There was no need for complex bureaucracies or corporate hierarchies; governance was rooted in relationships and trust, with leaders held accountable by those they served. This shift wasn’t easy. It required people to learn new skills, to navigate conflict, to listen and compromise. But it was worth it, for in transparent governance, people found a new sense of agency and dignity, a reminder that they were not passive subjects but active shapers of their own lives.

The final principle of the covenant was Collective Healing. After generations of trauma, exploitation, and isolation, people carried wounds that could not be healed by policy or infrastructure alone. True freedom required healing—not just of individuals but of entire communities. Healing was not something people did in isolation but something they did together, creating spaces where people could share their pain, confront their fears, and find support.

Collective healing meant investing in mental health care that was accessible and holistic, addressing not just symptoms but the root causes of suffering. It involved creating community rituals, spaces where people could process grief, celebrate resilience, and mark transitions. There were circles for storytelling, where elders shared their experiences with the younger generation, passing down wisdom and resilience. There were gatherings for collective mourning, where people came together to honor those who had been lost to the plagues of addiction, violence, and despair. In collective healing, people found the strength to forgive, to rebuild trust, to believe in the possibility of a better future.

Each of these principles—mutual responsibility, ecological harmony, transparent governance, and collective healing—formed the foundation of the new covenant. Together, they created a framework for a society that valued people over profit, relationships over transactions, care over control. This covenant was not enforced by laws or police but sustained by the shared commitment of those who believed in its vision. It was fragile, always in need of renewal, but it was also resilient, grounded in values that could not be bought or sold.

As the new covenant took root, the world began to change. The plagues of American Jesus did not vanish overnight, but their power weakened as people chose a different path. They lived not in blind obedience but in conscious partnership, building communities where each person’s gifts could flourish, where the earth was cherished, and where life was celebrated in all its messiness and complexity.

In this new covenant, people found a freedom that was deeper than independence. It was interdependence, a sense of belonging not only to themselves but to each other and to the land. The journey was far from over, but they walked it together, with hope as their guide, bound by a covenant of care and compassion that no empire could ever break.

#queer artist#chaotic good#original art#i’m just a girl#third eye#artists on tumblr#original thots#spotify#writers on tumblr

0 notes

Note

ayaansmomsdadvoiceUGHHUAHAGAH I CURSE YOU

wtf... how does this prove youre not racist 🙄😬

#ayaan can you do that voice again for us#me and ty dressed up in vicotorian orphan say this#TY#ASKS

1 note

·

View note

Note

Can I ask, what's the beef with Greg Ellis and Mark Darrah? I haven't been keeping up with BioWare in general and the Dragon Age fandom & company division in particular (I'm more of a Mass Effect person) so all I noticed is that two big names (were?) quit a few days ago so I am genuinely puzzled at that exchange. Did Ellis get screwed over by BioWare/Darrah somehow or is he doing some unfounded shit-stirring?

Oh for sure, so I don’t know all the details, but I’ll try

Greg Ellis

Greg Ellis is the voice actor for Cullen, a character who is in every Dragon Age game. the actor has been a pretty shitty person for a while—I’m sure there’s a callout post for him somewhere on tumblr—but he’s the British equivalent of a Trumper, transphobic, hosts a podcast/contributes to/does audio readings for a right-leaning website that complains about liberals and universities, often gets into fights with LGBT+ folk on twitter and block them (so many that a lot of DA fans couldn’t read his tweets today lol).

[ID: Greg Ellis tweet: “I praise @Ayaan for supporting @jk_rowling in standing her ground. They are heroes of our times. /end ID]

[ID: Greg Ellis tweet: “Today on The Respondent @GreggHurwitz discusses the challenges of identitarianism on college campuses. /end ID]

From Wikipedia: Identitarianism: “The Identitarian movement or Identitarianism is a post-World War II European far-right political ideology which asserts the right of Europeans and peoples of European descent to preserve the culture and territories.”

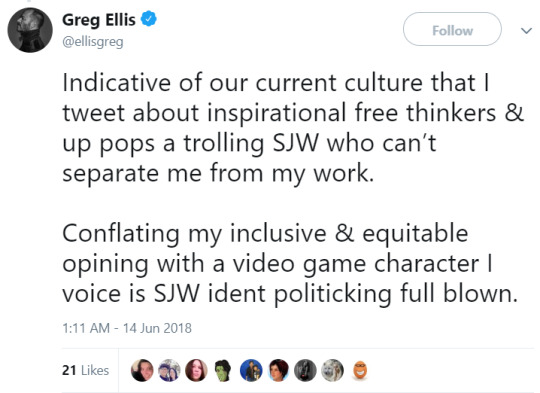

[ID: Greg Ellis tweet from June 2018: Indicative of our current culture that I tweet about inspirational free thinkers & up pops a trolling SJW who can’t separate me from my work. Conflating my inclusive & equitable opining with a video game character I voice is SJW indent politicking full blown.”

Greg Ellis tweet replying to a disappointed fan who was upset about his support for Trump: “Speaking ‘on behalf of thousands of fans’ of a video game & suggesting I ‘broke their hearts’ because I support ALL who hold Presidential office is ludicrous. VG fandom is not exclusive to LGBTQ or those not hate filled about @potus. I believe in equity & inclusivity.” /end ID]

to demonstrate how much of an attention-seeking child he is, Ellis also likes to tease his fans with hashtags and get them up in a tizzy to gain followers, tagging things #Cullennites and #DA4 just to wind up bait-switching and actually talk about something completely different, or maybe even nothing.

[ID: Tweet from Greg Ellis, I don’t have the date but I believe this was from spring of 2018: “I’ve been officially authorized to disclose details about the game only when I reach 10k followers. I feel like a puppet. Will you help pull the strings? I’m positively itching to share. #videogame #announcement #cullenites” /end ID]

Beef with Mark Darrah

I think what specifically started his beef with Mark Darrah was this summer, Ellis tweeted in support of Ayaan/JKR (above), resulting in a lot of upset fans replying to him. He got in lots of fights with them, blocking several, prompting fans to make more tweets expressing anger/disappointment about DA4/the future of Cullen, and even tweet at other Dragon Age developers asking if Cullen could be recast if he comes back at all.

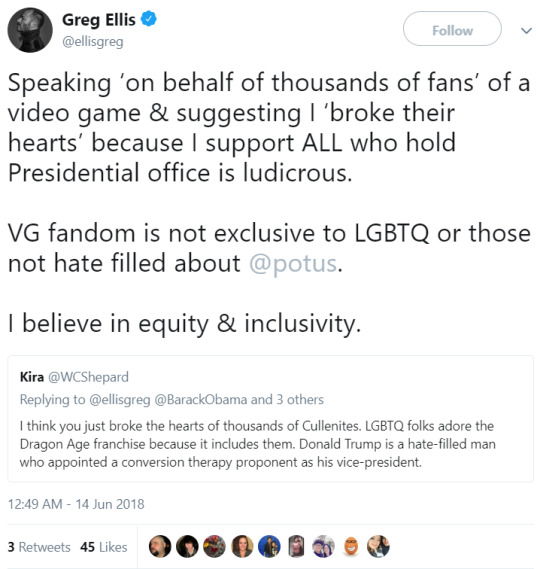

Mark Darrah made a tweet saying basically nothing substantial about it, but he said: “It’s important to us that the people we work with are aligned with our BioWare values. This will be apparent when we’re ready to announce what actors will be lending their voices to the game.” He even replied directly to a few fans throughout the tags/search results who were concerned, including @theherocomplex which I saw, so it’s a safe assumption he was at least taking the anger seriously.

Ellis replied to the public tweet: “What r the @bioware values @BioMarkDarrah? Don’t the loyal #Cullenites & @dragonage fans have a right to know? Don’t u have a responsibility to tell them? DO u support cancel culture? Do u support defamatory comments like this? Careful how u answer ~ u might lose ur job”

I mean, it’s pretty ballsy to threaten a lead creative at a company responsible for a chunk of your fame when your character’s arc is effectively over and they don’t need to have you in any games anymore... there are tons of crappy British actors out there to replace you, and it’s not like they don’t already have Gideon Emery in a dozen different wigs, lmao

What Happened This Week (Dec 3 and Dec 4, 2020)

Mark Darrah was, until recently, a staple in the Dragon Age team. A lot of people were worried when his resignation yesterday came out of the blue, and Casey Hudson (also a lead creative/big name) also resigned from the Mass Effect team at the same time, which to me is pretty concerning.

Yesterday after the news broke, a fan asked Darrah if his beef with Ellis might have had anything to do with his departure (basically asking if it was a forced resignation): “If this has anything to do with a recent blowout with a VA from Inquisition who publically called for @BioMarkDarrah to be fired, I'm going to be so sickened and disappointed by this company for siding with bigotry.” Darrah replied with just “lol” which to me was a little concerning, because if you read it sarcastically, it seemed to imply the drama with Ellis did have something to do with it. without proof, it’s difficult to say, and of course Darrah and Hudson gave polite goodbyes but are silent on the real reasons that prompted them to go.

Today, Ellis has managed to convince himself that he did get Darrah fired, likely over the stink he raised about Darrah publicly for siding with LGBT+ fans over him. but in his replies to that, Darrah mentioned pretty open skepticism in his tweets that Ellis would ever be rehired by BW again, so.... maybe the Ellis drama is not it. IDK.

TLDR: basically, Ellis is a bigoted right-wing voice actor who picks fights with fans who call him out, and he is still coasting off the attention highs he got from voicing a highly controversial video game character in a franchise that hasn’t hired him since 2014. in summer 2020, Ellis threatened Darrah’s job (not at as if he has any power to threaten him with), basically because Darrah stood up to him, and now that he no longer has to play civil as a BioWare employee, Darrah finally snapped and called him out on twitter for being unprofessional and implied Ellis wouldn’t be asked back to BioWare anyway even if Ellis WAS the reason he left. other Dragon Age developers (who still work at BW) are liking and replying to Darrah’s tweets with supportive gifs/emojis, so I think it’s a fair to say Darrah’s attitude is prevalent in the company but current workers just can’t say anything, and they do not want Ellis back again.

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

DVD commentary for matrvat?

The thing to know going into this story is that @parlegee is the absolute greatest for giving me open-ended prompts because I feel lost when there’s no prompt and sometimes constrained if it’s too specific, and there’s zero chance i’d have come up with this story in either case. Now, onwards.

---

Who is an opinionated teenager who can’t really allow adults their weaknesses? Krishna is!

“I thought he was a great king,” Krishna says disconsolately one morning as the sun drenches golden every wall of Rohini’s favourite room in Vasudev’s palace. The garden outside is fragrant with a dozen bushes of champaka flowers reaching for the light, and resounding with the laughing voices of Vrishni children and youths.

On such a day in Gokul, in Vrindavan, Krishna would be dancing through fields at the head of the pack, creating mischief and music in equal part. He used to come home along moonlit paths and worry Yashoda, whose heart was more tender than Rohini’s hard-shelled own.

In the ordered gardens of Mathura he skulks into the council-chambers of kings and nobles who have survived Kamsa’s scourge, and sulks in Rohini’s chambers.

If Krishna was even 10% less sunny than he is, he’d be in screaming fits the whole time. Rohini doesn’t really know it yet, but she’s aware of the general shape of it.

Rohini, who has missed Mathura’s high towers for longer than he has been alive, understands his longing only too well. Among the laughing children in the garden are the sons and daughters of women she befriended as a young bride, children who have never known her, who regard her sons with awed suspicion.

“King Ugrasena,” she asks now, careful to keep weariness from her voice. “He was, years ago when we were young and he was in his prime. But he had a grown son who kept him imprisoned, and deprived him of the joys of consorting with his grandchildren.”

He’s aware of the more visible wounds on the others, but he’s still. He’s sixteen; he’s a kid; and he hasn’t really learnt to accept that a lot of people just are weak.

“I meant my pitamaha King Shurasena,” Krishna says, and urgently adds, “I would not trivialise my matamaha’s suffering, or that of my parents, nor their resilience.”

I’m very proud of this association, ngl.

“No,” Rohini assures him. “I misspoke. You have been kind to them as to a day-old calf.”

That is praise he understands, and Krishna’s face blooms with joy. Her wild, wicked youngest. Her poor boy, whom they have transplanted into such strange soil.

“Will you say of pitamaha too, that he has suffered much, and is an aged man to whom I ought be kinder?”

He says it as though he knows the answer already, and comes quietly to sit at Rohini’s feet when she beckons him. If it is all so unfamiliar now to her, the floors of white stone, the fittings of brass, the plenitude of silver and gold, how much stranger must it be to him?

This is all canonical, btw, and I totally did a quick skim of Harivamsham for this fic, which may have been a bad idea, but anyway.

“We heard his praises, when I was a child,” she begins. “That he had been a great warrior in his youth, and was favoured by the gods. And it is true that he has had his own sorrows, with his queen dead from grief for your father, and with his eldest daughter sent to fill the nursery of a friend. Then too, without his son at home he gave your aunts in marriage to kingdoms that have not prized them as they ought be, and it is a great burden to any parent to know their children unhappy without hope of rescue or redressal.”

“However?” Krishna puts in, and grins wide and wicked. If she hadn’t known him since Yashoda brought him to her house to play with Balabhadra, she would think him sincere.

This is still going to take a very different strength.

Well, he has been battling monsters since he was a suckling babe.

“When I was a handful of months older than your brother is now, and there was first talk of me wedding your father, my uncle spoke to me of the household I was to enter. Your pitamaha is an amiable man, you’ve seen this already. He is chief among the Vrishni, who are not the most peaceful of the Yadavas. You are too clever, surely, to not know how a man of sweet temper might become chief of such rowdy princes?”

“He was the man all could agree upon,” Krishna says on a sigh, and she rewards him with a hand smoothing over his hair. He wears it still in a mass of curls barely restrained by a fillet, but it is of bronze silk now, and not the undyed ribbons he had used to steal from unwary girls. Good, he's learning; to take aught from a Vrishni girl unawares rarely bodes well.

The Vrishni and larger Yadava politics are fascinating, and also this is bb!Krishna’s first lesson in politics and manipulation.

“He was given to pleasing men and creating compromises that nobody else could. It is a necessary skill, and your father had it also. Perchance he still does.”

“Do you doubt it?”

IDK about Rohini’s mother, but mine firmly believes everyone has a quota in everything. Also I wanted to introduce her longing for her own parents early on, both for the parallel to Krishna’s longing for his childhood and also to balance out the payoff at the end of the story.

“My mother used to say when I had climbed too high in a tree or gorged myself on mangoes in summer heat, that we have a share in the world’s joys and might spend it too soon and find ourselves in sorrow’s shadow.” It is strange now to think of herself as a child, when her mother’s hair has turned grey, silver, white with age and yearning in distant Bahlika without Rohini around to care for her, when she had been given in marriage to Shurasena’s son because the Vrishni let their wives travel often and her mother could not bear to part from her for long. In the first five years of her marriage she had visited often, rarely in the seven unhappy years that followed, and never in the seventeen that have since lapsed.

“You’ve said it to us often enough,” Krishna points out, and when Rohini looks down she finds that he has turned his head under her hand and is fixing her with a stern eye. “Do you think it is the same for a skill?”

... not that Krishna is ever going to hit hard limits on his own capacity for anything, be it love or war or politics but the rest of us aren’t a shard/iteration of the God who Keeps.

“They tell me skill in war increases with every battle. I know little of war, and even your father never won Devaki with his own prowess. But a singer can sing herself hoarse, and a callous herder milk a cow dry. Your father kept himself alive while helpless, and kept your mother alive while she posed a great threat to your uncle, and he kept them together when solitude would have driven them wild.”

“You think him brave!”

And again, [wonder woman baby.gif] Krishna is going to become someone who understands bravery beyond the physical wonderfully well, and his Mom’s here to guide his first steps down that path.

He is so young, Krishna, for all his valour and all his wit. So young, even though it seems most days that he knows all the things there are to know, that they are alive only by his grace. But he is sixteen, scarcely, and she is near fifty years of age. He has hardly seen anything of the world.

“I think him clever,” Rohini says. “Valiant, too, but not in the way of warriors who gain great renown in battle. He crossed the Yamuna in full flood for you, dearest, and then returned to Kamsa’s prison where he saw every day for sixteen years the spot where six of his sons had had the life smeared from them.”

This is Krishna & Yudhishtira’s one great similarity, in my head: the wish for more brothers to hide behind. They deal with it differently, but it’s there for both.

“I might have had brothers,” he says, and flashes her an apologetic smile. “I know I have one, but even that knowledge is new to me. I never thought I could love him more dearly than I did all my life, but in this I am happy to be proven wrong. But I might have had more.”

All these lives gone to suit a fearful man’s cruel paranoia.

“Kirttimat would have been twenty-five,” Rohini says, more to herself than him. “We would have been hunting out a bride for him. Then Sushena and Udayin and Bhadrasena, what strength they would have lent us in council, perhaps in war if they more closely resembled your matamaha than your father. Rijudasa and Bhadradeha would have still been in the care of their preceptor, and Balarama preparing to take Rijudasa’s place. And then you, youngest and most indulged.”

... let’s not think about the knives in Yashoda’s heart right now.

“Aren’t I so still?” Krishna laughs, and she thinks that this would not fool anyone who knows it well, that it would knife through Yashoda’s tender heart were she to hear it.

Vrishnis gossip. It’s what they do.

“You are the jewel of Mathura, best-beloved of an entire city,” she assures him. If there are rumours, they will be quieted soon. Of course there are rumours. Rohini has not lived in the city in years, but she knows still too well how the bees buzz in their hives, how gossip sings through the streets on the fleet wings of the mynah.

“You might have had more sons as well,” Krishna says, as though he likes the thought of being rendered insignificant by a horde of elder siblings, of being safely the infant of the family instead of the lauded hero who has battled demons and killed grown men.

Look, I never said I was a nice person.

“I would have liked a daughter,” she tells him, trading truth for truth. In Vraj she had looked at lissome young Radha and thought, if only Vasudeva had given me a child the year we were first wed. She had delighted in Radha’s friendship with Krishna, her amused tolerance of the boy following her around and sharing her chores: rare forbearance from a woman fifteen years his senior but oh, understandable.

He got away with so so much. In the song listing out Krishna’s hundred and eight names it says, “Ayaan Ghosh dubbed him Rage Douser.” Ayaan Ghosh is Radha’s husband and Krishna’s uncle, and knows about their affair, fwiw.

How could anyone resist Krishna’s laughter and his tricks and his charm? Yashoda and Nanda had never disciplined him; Rohini herself, who could rain recriminations upon stolid Balarama while the sun ran from morning to noon, faltered before she could devise a punishment for Krishna.

“You might still,” Krishna offers. “I should like a sister.”

Older people falling in love again is My Fave. Look, I read R/S fic at a formative age.

“If the gods will it,” she says repressively, as much to ward off her own blushes as his impudence. She has missed love, and Vasudeva’s arms around her are still the best home she has had, even though they are grey, even though imprisonment has sapped his vitality.

Ohohoho, just you wait, Rohini, he’s going to find every use possible for it and then some.

“You missed him, all these years,” Krishna says, because he has always been far too perceptive. When he was a child he had mostly used the knowledge to ferret out butter and ghee that had been stored out of sight; what uses he will find for it in a squabbling nest of nobles hardly bears thinking of.

“I’ve known Vasudeva since I was a girl climbing into womanhood and he was a boy proud of his first beard who could persuade a roaring council-hall into acquiescence. We were wed for years before Sini won him your mother’s hand,” she tells him. “Of course I did. But I had Balabhadra, and I had a share in you, and I had my duty before me.”

“Duty,” Krishna says, desolate again, and younger in his silk and gold than she’s ever seen him in torn cotton and mud. “And now I must do mine, when so many have given their lives for mine.”

“So many have had their lives won by you,” Rohini corrects, and stoops to press a kiss into his curls.

Dearest and loveliest of boys.

He smiles up at her as she straightens, but it is still a wan little thing and melts her heart as none of his sulking ever has.

“Come,” she says, “you have months yet till you must go to your preceptor. It does you no good to intrude on your elders' councils.”

“What would you bid me do instead? I can hardly herd cattle in this fine city, and there seem no demons about for me to defeat.” He looks so quietly unhappy, her heroic son, her child who has lost the mother who raised him and cannot yet love the woman who bore him.

“You might have had more brothers if the gods had not wished them away,” she says instead of offering platitudes he would only despise, “and it is your right to mourn them. But you have cousins you might grow to love, who will be your allies as all of you grow to take your part in grihasthashram.”

He hones right in on his eventual favourites, but alas, there’s obstacles incoming.

“I thought they were in exile,” Krishna says, but now at last something is sparking to life behind his eyes. “My aunt Pritha and her children, I thought they were wandering in forests with King Pandu.”

Of course he thinks first of the ones deprived of their rightful homes, the ones who might be discomfited by palaces as he is himself.

“You have other aunts,” Rohini says in lieu of laughter. “Your pitamahi Bhojya had many children, and though King Shurasena was generous in giving them to such of his friends and cousins who—childless—were fated to roast in the hell, Puta, yet he kept his eldest son your father, and he kept his daughters Shrutadeva and Shrutashrava.”

“Their marriages are unhappy, you said.”

“And yet not childless,” Rohini says carefully. “Your aunt Shrutashrava has borne Prince Damaghosha of Chedi an heir, and I must visit if your mother cannot. We may travel without too large an escort of guards.”

“You would have me come with you?”

I just want to share the fact that family trees which start tracing lineages from the Sun and Moon still don’t show what family Rohini comes from and I had to read the Harivamsam to find out. I resent this fact.

“Only if you wish it as well. Then, too, Bahlika does not lie so very far from Chedi, and... Krishna, as you are in part my son, so too can I offer you a share in another matamaha and matamahi. My parents are old, and shall soon proceed into sannyasashram, but they are hale and they have always been happy. King Ugrasena is a great man, but...”

“Mother,” Krishna says, snatching up her hands and covering them with quick, fervent kisses. “You give me the sweetest gifts.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

III, Going to School

Tief didn’t have dreams. He didn't have a stroll through his memories this night, as well.

But now, he woke up with a long gasp, panting in fear remembering what happened to him that night. Was he dead? Was he-

It was early morning, sunrise. And around him, the room was painted red and black in letters he didn’t know. Many, many letters written in blood were inscribed on the walls of the room, and on the ceiling there were two pure white skeletons with their mouths opened wide, as if in their last moments they cried loudly in fear and pain..

`Tayem’hosekem webhoht dohteser vekem iya’tayem gethe’tayem iya’tayem...`

He could read it, this was written all over the place. Whispers, dark voices that made him shiver.

The whole room was the result of what he’ve done. Of his nature. To save himself he killed two others. And now Tief was pale, almost colourless in face. He wanted to throw up, he wanted to run away.

Trying to ignore the whispers in his head which he believed was his subconscious, he packed his things and dressed up, with his hands trembling and breath shaky. Tears in his eyes. His lute wasn’t damaged anyhow, not a scratch, and the money was intact. Tief then looked outside (his room was on the second floor of the Duglew Tavern), and thought to crawl through the window to avoid meeting anyone.

Opening the window and trying not to look at the walls painted with blood and unholy symbols, he exhaled, and with a wicked maneuver jumped down, rolling and standing up on his feet without anything damaged.

— Curse you, curse you, curse you… — He mumbled under his breath, walking as far as possible from the tavern. His heart was rushing again, but to his surprise, his back didn’t hurt anymore. At all.

Tief walked to some alley between two gardens and leaned on a wall.

— Think, think you poor bastard… — He spoke to himself, thus motivating himself to think.

This letter was suspicious, but how would he know it was true other than go and check himself? Tieflings are known for their chaotic raw magic and fiendish nature. What if it’s a cult where they will force him to learn bad things? What if it’s a trap made up by some… Inquisition of sorts? At least three churches didn’t like any demonic creatures

But what if it is a school for tieflings, just like him? He thought a little.

Dark skinned people with glowing eyes and claws, feral long feet… He never saw anyone of his kind before, only on an illustration from some book written in Revenlandish. He thought most of them should be red, as depicted in the manuscripts, but him? What if he wasn’t even a tiefling but some… Other kind of fiend, or something?

What if he wouldn’t be allowed there? He checked the letter twice. Tief knew, at least he thought he knew, that he is the only street bard tiefling child who played songs on the streets of Serreip Sed district.

If it’s a real school, then he could walk there and meet others of his kind, have friends, maybe a family… He could play songs with them, he could play games, he could have food and a comfortable bed…

Then, Tief remembered this night and thought about his powers. He didn’t know how he casted this strange spell that deformed the two men so much, and didn’t want to cast it, at least consciously. Potentially it was very powerful, and though he knew nothing about magic, Tief accepted the fact he could use it in a defensive manner.

Now, he has decided.

— I am going to school, Seth.

…

After walking to the other end of the town, he found out it’s name was Regagne. And also he felt that he wasn’t welcome here. He knew it by looking at the behaviour of street cats. Any place must be judged by cats. If they are angry and anxious, then the place is bad, and if they are not afraid of you and come near to let you pet them, then it is obvious the neighbourhood was friendly.

There, cats were easy to be scared off, and mostly were sitting away from everyone and even each other.

Tief was looking at the singboards while wandering through the marketplace. He hid his money in several places, the golden galleons he had in a small pocket on the inside of his pants, half the others he had in his pouch and the rest was wrapped in the letter.

There was a weaponsmith, some old woman was selling metallic jewelry, a shoemaker, a butcher… In the distance Tief saw a familiar face…

It was the old man with the cart of hay! It was all empty now, and he was talking to some good dressed man. Tief decided not to bother them.

The young tiefling bard walked to the shoemaker and into his little shop. It smelled of leather, dust, and a little bit of oils and iron. All aroung the place, on the floor, on the walls, hanging from the ceiling there were boots, shoes, low shoes, snow-boots, riding-boots, farmer-boots, sandals…

An elderly man with no hair on his head was sitting in the corner by the window, working on some nice pair of boots: black leather, colorful laces… His back facing the entrance of the shop, he spoke in a gentle and tired voice:

— Rodrick, are you there? Go see who just came…

Tief looked around the shoemaker’s shop once more. It was comfortable. Several chairs were around, every shoe was clean and smelled of oils. His head felt dizzy from so much freshness. He inhaled the air and sighed in surprising relaxation.

From behind the corner, from another room there came a curly headed peasant boy. He looked at Tief and suddenly shouted, scared. Tief covered his ears.

— I’m sorry, I’m sorry…

— Rodrick, what in the hell are you- oh… — The man was now looking towards Tief. He had no eyebrows, a very wrinkly face and deep blue eyes. Rodrick already hid in the other room which seemed to be a storage.

— I’m sorry sir, I didn’t want to scare anyone I’m just-

— You should never, ever, ever apologise for being what you are, young man. — He spoke in a solid Brotteonian accent, saying words whole and having a strong note of something in his voice. This was something very difficult to explain in words… As if this man has seen a lot in his life, as if he had some discipline in him.

— I-

— Pardon Rodrick, he never saw someone like you but I did. My name is Ayaan Cempbill, how can I help you young man? Are you looking forward to buy some shoes?

— Yes mister Cempbill, I am. But I am now uncertain you will have any that will fit me…

— Why so? Take a seat young man, let’s see what’s the case. How can I address you?

— You… You can call me Tief.

— Tief? Do you know how degrading it is? Is this a nickname you got from your locals?

— I… Yeah, it is.

— Well, let’s see then, Tief. Sit there, please, — He took a chair and offered it to Tief, who was fairly shocked and confused on how to behave. Mister Cempbill was walking as if he was bent in half, and now was coming to see Tief’s bare feet.

— Ooh, wow, that’s new for me… Don’t mind me Tief, can I? — He sat on a small little chair and looked at Tief’s right foot which he held in his hands right now. Tief was a little startled and somewhat awkward.

Tief’s feet were a little elongated, his toes were a little bit like those of a feline, with claws and pretty agile, his pinky toe was on the side of the foot, not on the front. He could grab small things with his feet, he sometimes used that to his advantage.

— Well, Tief, I see. I rarely worked with anything like that. Your feet probably won't fit into any of my shoes, hmm… From your point of view, how do you feel walking barefoot?

— Pebbles. They hurt a lot if you step on them while runnin’. And nettle, and any other prickly plants…

— I see, I see… How much time do you have? I have something that might fit you, it will take an hour to adjust but it will then be yours. Come on, — He patted Tief’s knee and stood slowly with a grunt.

— Stay here… I hope you have some time, I just need to measure you, you know, — He walked to the room in which Rodrick was still hiding, and came back with some strange ribbon.

— Alright, give me your right foot, — Tief didn’t quite like being examined like that, but couldn’t do much against it. Mister Cempbill then placed it on his own knee and wrapped the ribbon around it.

— What is this?

— This? It’s a measuring tape, want to have a look? Just one moment… Half a dozen aprox and then… — Mister Cempbill mumbled some numbers and stuff. Tief suddenly realised he didn’t know how to count right. He knew many numbers, yes, theoretically speaking he could count to 999 999 (because he didn’t know what a million is). But he couldn’t do anything other than simple addition and subtraction. — Alright, this and that… — Mister Cempbill’s face went illuminated as some idea came to his mind.

— What is it, mister Cempbill?

— I know exactly what to give you, one minute Tief, — He hurried to go somewhere and looked among the materials he had. — Here, let me check…

Mister Cempbill sat by him once again and put something on his right foot. It was something like a leather shin guard, but the point was that Mister Cempbill placed it on Tief’s foot, not the shin. Now he looked for something else, asking Tief to hold the thing on him. He returned with a pair of sandals.

— Alright, put your foot in the sandal and tell me how you like it, — He gave Tief the footwear and looked down thinking. Tief put it on and… It was rather nice, but a little stiff for the arch of his foot…

— Don’t worry about anything but the toes: how do they feel? Comfortable?

— Pretty good, yes…

— Excellent. — Tief didn’t know that word. But he assumed it was some kind of exclamation.

In a matter of half an hour, Mister Cempbill had a strange pair of something that wasn’t exactly boots, but not sandals either. These shoes covered the toes from above, but not from below, they were comfortable to walk on tippy-toes with and with the full foot. This was some…

— Magical…

— Oh don’t you say. About the cost, let me think…

Money. Tief froze in place. These shoes were custom made, and surely cost his whole fortune… Should he run with them on his feet? Then he wouldn’t get to buy anything else before heading to Amperholm…

— Let’s see, what is your money in count, fairly? I can hear the clinking of the coins, you have a lot, but the question is… Hm… Alright, four silvers will be fine?

— F-four silvers!? S-sir that’s fairly too… This price is too low for such good shoes…

— The leather cost me half a silver. The sandals were a donation from a woman I know, other than that working with this gave me some more experience on the subject of unusual feet and it only took me three quarters of an hour. This is a good deal for me, so don’t you worry…

— Sir… — This was like a blessing. Never have been someone so nice to Tief. He was feeling emotional, and Cempbill was smiling nicely at him.

— Come on Tief, you have places to be. You will thank me some other time.

…

Tief walked out of the town completely different. With mister Cempbill’s help he got to buy himself some nice clothing, and near the high-noon, he headed south-east where the Amperholm lands were, and where was as well a lake where he could bathe. With some sheer luck, he didn’t encounter anyone who would say anything about the mysterious murder last night.

He walked the road, feeling this light emotion on his soul, dressed like a well-to-do person: a white clean shirt, a leather jerking on it, breeches of brown colour, mister Cempbill’s tiefling-boots (that’s how they decided to call them, together), a small rucksack on his back. together with the lute. He even bought a little knife for self-defence, and some foods he placed in a linen wrap. He also bought three cheap expense notebooks from yellowish paper from the local stuff store. Several pages were torn out, it seemed like someone bought them, used them for some time, and then found them useless.

And he still had almost a whole golden coin on him!

Tief felt so happy he wanted to sing. He needed to do it.

Taking out his lute from behind his back, tuned it a little, and walked like that for a minute or two, thinking about what song to sing.

He decided.

— A, bee, cee, bee...

`Way o’the road

So damn long and dusty,

When there’ll be a route

To the only right way?

Mountains

And the fields

Wind and rainy weather

Will we ever stop ‘ere

To look up at the sky?

To look up at the sky-

Roads of dirt and

Bloody rain

Roads of dust

And wind - insane

Where’s that mountain

Where’s that hill?

Where we will learn

How to feel?

Roads of dirt and

Bloody rain

Roads of dust

And wind - insane

Where’s that mountain

Where’s that hill?

Where we will learn

How to feel?

Maybe all this is wrong

Maybe if we all are together

Maybe the day will come

So we could look up the skies

Till forever…`

…

Tief made his way to the lake he heard about in the village. Looking around and checking if no one was looking, he found a private place between two willow trees and sat there to take a break and a little snack: one and a half round buns, some dried plums, and a strip of sun-dried bacon. He felt good, it was a nice time. Tief assumed he would be around the School after a day or two of walking. He checked the letter once more. Cargealdor village… It must be some thorp or something.

Tief looked around once more to see if anyone was around.

The lake was big, set between two steep hills, and had a crescent shape. In the high noon the sunlight was playing in the water, reflecting in all kinds of ways. The water was not so transparent, but seemed clean. Tief thought twice, and decided to have a bath since no one was around.

Undressing and hiding his clothes under a bush together with everything else, he walked to the water and stepped in. It was surprisingly warm: it seems like the summer heated it up a lot. It was so nice…

The tiefling teen washed himself all over, cleaned his hair clean. Finally it had it’s whitish colour back… In the Serreip Sed district he needed to look miserable to get more attention from the crowd when he played the lute. Now he thought:

— I will be clean, beautiful and nice…

He washed his face, his armpits, his legs, his hair and neck…

From the water, to the lakeshore, there walked a handsome young tiefling with skin of bluish black, glowing amber eyes and white, grizzled wet hair. His skin shone on the light, clean and smooth, his tail with a little spade on the end swayed behind. He was slim and had almost no fat on him.

Dressing up in his underclothes, he laid back and ate some more of the dried fruits he bought. Looking at his reflection in the water, he was surprised to see how well he looked.

He wasn’t religious, but prayed for anyone who could hear him. He thanked the lute, he thanked Seth, he was thankful for all the good people he ever met. Tief was slowly moving towards the light, and was so happy about it.

In Serreip Sed there were two churches: of Ueid, the Revenlandic saint god, and of Ael, god of angels. In neither of these buildings he wished to find himself, for ueidians sometimes were rather cruel, and aelians proclaimed that everything they do is holy because it’s them who are doing that. Many old women and men, and other fanatics of all ages were always following Tief, shouting bad words at him. Some believed that Tief himself chose to become a tiefling and that he was a sprout of evil no matter what he did.

Once there was a story, that a local son of a baker bought a guitar and sang on the Square of Doctor Ernest Giraud (a local hero who almost single handedly stopped a plague outbreak but sacrificed his life). The baker’s son played not so well, but soon he left the square with so many coins in his hat it probably weighed around four pounds, as Tief thought.

On the next day Tief came to the same square and sang his own songs. He was almost beaten up, just because of his race., but managed to run away.

Tief knew he played better than the baker’s son. He knew it, he believed in it.

The high noon was falling and it was around half past one when Tief continued his journey. He found a straight good stick which he used to ease the walking (and if needed, he would use it as a weapon).

He walked forward on the road paved with dirt and ancient rocks that eroded long ago. He walked and stopped for a break every horizon. Horizon was an old measure of distance, it was also called ophelde, which in some old language meant “rest”. He could walk a horizon in around an hour, take a quarter-hour rest, and then continue. Towards the end of the day he was so far in the fields he didn’t know where to head. Tief tried to count how much he walked. Around 7 horizons. Now his legs hurt as he was making a little camp by the road, behind a little hill. The sun was setting, and he had to hurry. He needed a fire, so he gathered some sticks from the several trees not so far away. The grass there was high to the knee, so he could see if someone was coming close.

— Fire’s needed, but I don’t have a flint… — He said with a sigh, looking away and around.

Then he thought a little. What if he tried to sing in his secret language and maybe the fire would spark?

He took his instrument and tried to think of any word in that language. It was so strangely difficult… It was as if describing something extremely simple, like, the colour green, without using the word “green” or any comparison.

— R… Rohtedoht? What is this even, I don’t know… — Tief mumbled trying to pick up a tune for it on the lute.

`Rohtedoht, rohtedoht

Lyrikekem bedtloodoht`

Nothing happened. The bunch of sticks Tief placed on the ground and surrounded with rocks (so the fire wouldn’t spread) didn’t do anything. Tief decided to repeat this little… Song he made up, eventually not knowing what it meant.

It was as if his mouth spoke by itself, as if his voice pronounced things he didn’t know, as if the language he talked lived a life separate from him.

— Rohtedoht… Rohtedoht…

`Rohtedoht, rohtedoht

Hefhed’rekem bedtudoht-`

That didn’t work either. Tief huffed annoyed.

Perhaps the nights aren’t that cold, he could easily sleep one without a fire. Tief destroyed the fireplace, throwing the stones and sticks in different directions and went to the trees nearby. There, throwing a wool coverlet over a branch low by the ground, he made himself an improvised tent, under which he laid on the grass on his back, and put the rucksack under his head. Then Tief slept tight.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 12

We are the robots

booop booop booop boop

Kraftwerk blared from Guy's stereo system as we made our way down to the river.

"I forget Powerade! Stop at Lure's Bait and Tackle!" Erin exclaimed as she saw the shiny gas pumps in the distance. Blue Powerade was our thing for some reason. Not sure how it started, but it definitely stuck. Guy pulled into the parking lot and parked by the vacuum and compressor on the side of the brick building. Erin ran in in an exaggerated fashion flopping her arms around wildly. We were both sitting in the backseat again. The front seat now had what appeared to be an antiquated computer case and an 8 track deck in it.

"Hey, whatcha gonna do with that case?" I asked Guy, somewhat sarcastically.

"Put a computer in it" he said blankly. Guy knew he had too much stuff, and it was a bit of a sore subject. I figured it would be better to just leave it alone, especially since we were all about to start tripping in around an hour.