#autononmous zone

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Live Sketching the Future: Insights from Liberty Conference

Liberty in your lifetime! Free cities foundation

I had the opportunity to live-sketch the Liberty in Our Lifetime conference. I captured its essence and the energy of the discussions around autonomy, free cities, and, of course, Bitcoin. It was an intense experience. However, seeing these pieces resonate with attendees made it worth every moment. They contributed to the cause. The sketches were auctioned off. The majority proceeds went to…

0 notes

Text

Owen Wright: The Sight of Sound

The existing literature on the relationship between music and the visual arts in the Islamic world, even if not extensive, es yet sufficient for an attempt at some sort of characterization. Broadly speaking, it can be divided into two generally unrelated streams. One is the interpretative and essentially unidirectional: rather that treat the two on the same footing, seeking, say, the elucidate possible economic functional, or aestehtic parallels, it ocncentrates on musical iconography – that is, it regards artifacts and paintings as source textes to be scoured for their musical content, whether from a primarily organological perspective, or as representative of social structure and behaviour. It has, therefore, potentially much to say about music, being indeed a vital visual supplement for the historical musicologist, otherwise largely starved of information about the morphological evoltuion of instruments. (159)

The other stream, even when specifically adressing connections between music and art, ventures by implication or design into the more speculative domain of the general world of culture. Assuming the operation at some level(s) of a unified vision, it seeks to tease out conceptual parallels ultimately reflective of an aesthetically and hence ideologically integrated universe, and consequently may also engage with other forms of creative expression, particularly literature. With regard to the visual arts, notions of abstract design and structure, rather than representation, have been emphasized; and particular attention has been paid to putative similarities between formal patterns of melodic organization and the recursive combinatorial potential of arabesque motifs. On the other hand, comfortingly if rather unexpectedly, little attention has been paid to hypothetical parallels with the geometry of floor designs, mosaics and muqarnas decoration that might have been suggested by the mathematical predilections of certain theorists of musc. (159)

Also hitherto neglected has been the ancillary tpoic to be addressed here, the use of visual representation and visual metaphors as explanatory devices in relation to music. (159)

But if we set aside the domain of rhythmic analysis, at times intimately (if deceptively) connected to prosody, we find that borrowings from the metalanguages of grammar and rhetoric are strikingly absent, and that the technical vocabulary of music, whether indigenous or Greek-derived, is largely autononmous. (159)

metaphoric vocabulary (360)

Among early theorists visual references resolve, broadly, into two classes: the associative and the explanatory. The former, grounded in cosmologically sustained networks that suggest arbitary collocation rather than causal relationship, appear prominently in the work of al-Kindi. (360)

Hearing, it is contended, is capably of more precise discrimination, as shown by its capacity to appreaciate meter and music, where it can recognize deviations in rhythm and melody; sight, on the otehr hand, is for mthe most part epistemologically unreliable, being fallible in its estimation of size, distance, motion, and regularity of surface/shape (360)

Various systems of graphic symbolization have appeared at different times in the MiddleEast to represent sound, whether in terms of duration or of pitch, but the most frequent used in the Islamic world has been the letters of the Arabic alphabet, usually, as here, in the abjad sequence and therefore with implied numerical values. (360)

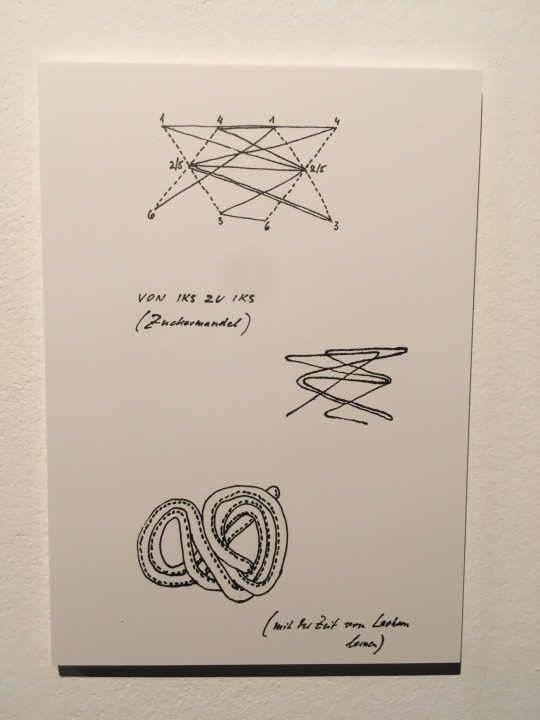

However, the central point here concerns not the reliability of the text or the accuracy o the interpretation, but the fact that the nature of such recursive note patterns is difficult to grasp from a reading of the graphic symbols alone. Intriguingly, they convey schematic (and wholly abstract) outlines that are categorized as shapes by their accompanying erbal labels and need some process of spatial projection in order to be understood as such. In fact, al-Kindi is thinking here in fundamentally visual terms: howwever litte we may know of musical practice of the period, it is contestable that considered melodically the notes given form implausible contours. Theoretical speculation, whether conducted by al-Kindi himself or taken over by him from no longer extant, post-classical source, is here being driben by the visual metaphor embodied in both the Greek term ploke (»plaiting«) and its literal translation into Arabic. (361)

The notion of circularity is repeated by Ibn Sina, who defines it in terms of periodic repetition of pitches within a given melodic span. He also takes geometrical analogy further b adding the concept of polygonal movement, and then allowing the combination »circulat polygonal«. (361)

But altough the figure if the circle is latent in the key term dawr, which we already find in al-Farabi, his analysis of rhythm is dominated by notions (361) od disjunction, gap filling, and gap creation, and it is only much later that we encounter diagrammatic representation in the form of circles. In fact, not until the aptly named Kitab al-adwar of Safi al-Din al-Urmawi does this method come to the fore. Thereafter, although not favores by every theorist, it becomes a standard displax format, being used not only to show the cyclical, repetitive nature of rhythmic structures but also to desplay consonant relationhips in modes (by drawing lines between the pitches in question) and the districution of pitches between modes; to serve as a frame for a novel form of notational display; and even, on occasion, to provide a model for setting forth cosmological associations. (362)

Of more interest is the way al-Farabi articulates another standard concept, the binary opposition between primary and secondary notes, that is, between those that are considered fundamental to a composition and those that are not. Two analogies are offered in clarification: textiles and buildings. Primary ntoes are accorded the status of warp and weft or brick and wood, secondary notes that of dyes, glossing ,decoration and fringes or, in buildings, that of adornments, appurtenances and facilities. (363)

When discussing the ways notes combine, al-Farabi again resorts explicitly to visual analogy, concentrating now on color. For notes in immediate (coadunative) association, perfection is compared to the combination of the boldly contrasting colors of the wine and the glass, of sapphire and gold, of lapis lazuli and red, while for notes in consecutive association, vaguer reference is made to unspecified colors in decorations and to a soccession of different and equally unspecified tastes. (363)

However, although al-Farabi's formulation does not, evidently, deny the representational and aesthetic dimension, it could be argued that it does provide some pruchase for a conceptual separation of structure and ornament. To the extent that it allows for the autonomy of the latter its emphasis is rather unexpected, for what prevails elsewhere is a basiv vs. Secondary contrast from which may be derived a hierarchical distinction of aesthetic levels or respnsens: the secondary, decorative element is viewed as something that supplements the (ontologically prior) essential, thereby producing an enhancement. (364)

Given the use of letters as a notational device to represent pitch, it was only to be expected that the metaphorical range of visual references would also include calligraphy. But if it is interesting to observe that calligraphy is referred to primarily by writers who use notation litte or not at all, it has to be conceded that the references theselves are not particularly illumination. (364)

Comparisons with painting also accour, but in a quite different and purely theoretical domain. As with al-Kindi's language-driven generation of visually conceived patterns, they stem from, or are fortiutously provoked by, teh vocabulary employed to translate Greek terms. For the classification of the tetrachords into three types – enharmonic, chromatic, and diatonic – the Arabic equivalents variously include mulawwan (chromatic) and rasim (enharmonic). However, the original notion of the »coloration« of teh chromatic genus being in some way an alteration of the »in-tune« enharmonic is, in effect, reveres. The enharmonic genus, which for Arab musicians (and even theorists) was a purely theoretical entity neveer incorporated into practice, is regarded is marginal and shadowy in contrast with the now primary diatonic genus, indicatively termed qawi. (366)

Since the common expresion of musical and architectural relationships through mathematical formulae appears not to have been invested with cultural significance, it is hardly surprising to find that in modern scholarship allusions to the geometircally abstract relate, rather, to mosaic tile patterns. The context is a comparative exploration of the nexus of the non-representational, the ornaental, and the arabisque that attempts to characterize music in analogous terms and to place it together with other arts, and especially the visual arts, in a single aesthetic embrace (367)

Faruqi: one concerns the targeting of improvisation, the other the notion that here ornament is all there is. The fist might be thought to imply that in composed pieces different norms somehow obtain: here, perhaps, ornament is an adjunct, and we arrive back at al-Farabi's analytical distinctions. But the second, in contrast, is semantically subversive, requiring the abandonment of the notion that ornament is a y that is added to an x in favor of an ontological shift to an undifferentiated zone of fluid relationships in which there is no hierarchical order: a highly democratic but musically suspect state of affairs. Equally problematic, it may be suggested, and similar in its implications, is the previous reference to a seeming boundlessness, an endless undifferntiated flux. It is difficult not to detect here an orientalist subtext – even if no doubt entirely unintended – calling into play such dubious oppositions as static vy dynamic and passie vs active, withn in this case, the inference of a musical practice lacking the progressive teleological urge frequently ascribed to Wester symponic thought (367)

Visual scanning, whether of a formal garden or an abstract design, is free to wander, return, reconsider, extrapolate – in short, to take its time. Auditory reception, on the other hand, may be free to vary its levels of engagement with the material it processes, but it cannot alter the temporal flow of a live performance, so that parallel recuperations of what had been previously heard can only work through memory, with the probable attendant creation of a narrative shape, especially when concept of mode are articulated in the form of tajectoriy of initial, medial and final events. Another problematic aspect may be summarized as physical and emotional envolvement. Whatever might be the meditative potential of contemplating visual arabesques, their musical equivalents an Arab culture – that is, if we accept the identifications offered – are much more likely to appear within a context geared towards the creation and heightening of tarab, an ecstatic state of emotional rapture. In short, their potential is dynamic rather than static. (368)

0 notes