#at least it only mentioned syllables and rhyme scheme

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

wanderlust

in silence there's an echo that comes from somewhere unseen speaking only to the heart of faraway places it never has been

#fictionadventurer poetry#poetry#a syllabic rhyming form from the spanish this time (an endecha)#at least it only mentioned syllables and rhyme scheme#i assume there's no set meter which is good cuz i didn't even try

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Lost My Talk - A Child's Plight

ID: An image of Shubenacadie school

Frankly, I don’t know where to begin. Essays, stories, they come easily to me. Putting argument or imagery down on paper feels like child’s play compared to this, for this is to convey my soul. That’s what poetry is, isn’t it? Poetry is the connection of souls, across time and thought and culture.

What is voice? A child could answer. Your voice is what you use when you talk, of course. But what is talk? And what happens when you lose it?

Let’s take a look at this poem:

I LOST MY TALK – Rita Joe

I lost my talk

The talk you took away

When I was a little girl

At Shubenacadie school.

You snatched it away:

I speak like you

I think like you

I create like you

The scrambled ballad, about my word.

Two ways I talk

Both ways I say,

Your way is more powerful.

So gently I offer my hand and ask,

Let me find my talk

So I can teach you about me.

Perhaps a child could answer that question. Perhaps too many could. But only a few have put it into words, and thus there are only a few windows through which we can look. If you skipped the poem, read it. I don’t think it’s possible to convey, with so many words, what Rita Joe conveys in so few. Should I attempt, I know I’ll only ruin it. Thus, you must read it.

Look at the title: “I Lost My Talk.” You can almost hear the child’s whimper, almost see the hands clutched to her chest. The phrasing is mournful, short with a childlike simplicity. It’s an epigram—it sketches out the atmosphere of the poem, even before it begins. Taste these sentences again: “I speak like you/I think like you/I create like you.” She uses parallelism, both in sentence structure and repetition. By repeating the word “like”, she also creates repetition. She speaks, she thinks, and she creates—Rita Joe uses these things to identify herself as a fellow human in a synecdoche. “Two ways I talk/Both ways I say/Your way is more powerful.” Here we see parallelism in structure again, as well as repetition by the repetition of “way”. “Way” in this case is a metaphor for a way of life. Rita Joe has learned the hard way that it is the white man’s path that holds the most influence, a tragedy and unfairness that she now presents before us. In addition, the First Nations would pass on their culture and wisdom through ballads and by word of mouth. Thus, the “scrambled ballad” in the poem is a symbol of the author’s culture and how it was lost. “Shubenacadie school” gives us an allusion to a residential school and the horrors experienced within. Thus, we can conclude that the people the author speaks to in an apostrophe are her absent abusers, or at least those who inherited their legacy. Finally, “offer my hand” holds connotations for reconciliation, peace, and forgiveness.

The poem itself is simple, without a rhyming or syllable scheme. It is written in free verse with a scattering of iambic phrases, such as “I lost my TALK” and “The talk you took AWAY” (emphasis added). The phrases are short, the words arranged in almost a song-like way, like the ballad mentioned in the poem. The author uses enjambment: “Let me find my talk/So I can teach you about me.” The use of enjambment emphasizes talk and connects the two; she wants to find her talk, her culture, not only for herself, but to share. The simple structure and the connotations of her word choice reminds the reader of the little girl that was snatched away from her family and plunged into a harsh and unforgiving place that cared not about her wellbeing. Does not your heart ache for this lost childhood? Mine certainly did.

But what is this poem about, besides mourning a lost childhood, a forgotten history? We find the answer in the last few stanzas. “So gently I offer my hand and ask/Let me find my talk/So I can teach you about me.” In these few words we find the poem’s theme of grace, forgiveness, and hope for reconciliation. After all, the first step towards peace is to understand one another, and how can they understand if nobody explains? We see the little girl, now a woman, surveying the ashes of her people and yet not growing bitter from them, but offering her hand to her absent abusers. Thus, the primary theme is solidified as loss and forgiveness, segregation and reconciliation. We see this reflected in the title: “I Lost My Talk.” Her voice isn’t angry, or vengeful, but mourning, and in the poem’s flow, we see her hope.

This is my favorite line: “The scrambled ballad, about my word.” As I mentioned before, ballads were used to pass on culture and history. “Word” here seems to be a metaphor for her culture and history. The author lost her heritage—not because it was completely gone, but because it was scrambled, muddled, made unwhole. I love it because it’s simple, it’s meaning half-hidden but rich. It shapes the poem. It builds its meaning. I wish I could ask Rita Joe if she ever felt like she got her culture back. Did she ever un-scramble that ballad? Perhaps she managed to find a person who could decipher the words and make them understandable again. Perhaps the plight of the lost child isn’t permanent for them all.

We see Rita Joe’s resilience all the more when we consider what Shubenacadie School really was. It was the only residential school established in the Maritimes, and from the day it opened it had issues with bad construction, terrible maintenance, and overcrowding. Children operating laundry and kitchen equipment led to some of them having serious injuries. In 1934, there was even a federal inquiry after nineteen boys were flogged until they scarred permanently. The judge in charge of the inquiry dismissed it, as “they got what they deserved.” (NCTR, n.d.) This was the place Rita Joe endured. This was the place where Rita Joe’s voice was snatched away. And, isn’t she one of thousands? Though she may have regained her voice, many never did.

Rita Joe was a little girl, once. She mentions this in her poem. It makes us wonder about the psychological impact this whole ordeal had on her. Did she struggle with anger? Did she struggle with fear? Though we see no evidence for the former, it does not mean that it didn’t happen. As for the latter, we may ask: why wouldn’t she struggle with fear? Perhaps she continued to have lasting psychological trauma, her mind locking her once more, perhaps even decades later, in the fear of a little girl. The violent words she uses, such as “lost”, “snatched,” and the begging cadence of the second paragraph may hint at such scars.

In identifying herself as once being a little girl, Rita Joe also draws attention to her gender. However, gender doesn’t really play a big role in the poem as a whole. One could even argue that it would be easy to change the words from “little girl” to “little boy” without changing the meaning or theme. However, it is worthy to note that as an indigenous woman, Rita Joe would have been vulnerable in ways she wouldn’t have been as male. In addition, the gentleness portrayed would typically be attributed easier to women than to men, as males would archetypically be portrayed as more vengeful, though this is not universal. Ultimately, we see from the other lines of the poem that it is not about man contesting with woman, but rather the unfortunately common archetype of human against human, race against race, First Nations against white, and so on. And thus, in leading us through this archetype, Rita Joe guides us to the conclusion that we’re not different after all.

Rita Joe learned to survive in the harsh world she was plunged into: “Two ways I talk/Both ways I say/Your way is more powerful.” Given her race as First Nations and her reference to Shubenacadie school, her childhood background could be assumed to be poverty or working-class. A quick Google search shows that to be true: she was an orphan by the age of ten and was forced into foster care (The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2017). She had no power, no money, a despised as a woman and despised as a First Nations survivor. But she held on to her identity as a human and didn’t let them dehumanize her: “I speak like you/I think like you/I create like you.” Throughout history, vengeance was considered a trait of resilience, but here we see true resilience in her forgiveness: “So I gently offer my hand and ask/Let me find my talk/So I can teach you about me.”

Poetry is timeless, and this one, with its message of a scrambled culture, the evils of racism, and hope of reconciliation is no different. Maybe, like me, you sometimes feel like the people of long ago were very different from us. But that is a lie—we all speak, we all think, we all create. In putting her story into words, Rita Joe reminds us that their plight is still relevant, and that they still matter.

To learn more:

youtube

Rita Joe – 1932-2007

------------

Sources

CBC. (n.d.) The Shubenacadie residential school operated from 1930 to 1967. [Image] Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://i.cbc.ca/1.6047377.1687271321!/fileImage/httpImage/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/original_1180/the-shubenacadie-residential-school-operated-from-1929-to-1967.jpg

Joe, R. (2007). I Lost My Talk. Poetry in Voice. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.poetryinvoice.com/poems/i-lost-my-talk

National Arts Centre. (2024). Rita Joe, C.M. [Image] Retrieved October 31, 2024, from https://nac-cna.ca/en/bio/rita-joe

National Center for Truth and Reconciliation. (n.d.) Shubenacadie (St. Anne’s Convent) Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://nctr.ca/residential-schools/atlantic/shubenacadie-st-annes-convent/

The Canadian Encyclopedia. (2017). Rita Joe. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 31, 2024, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/rita-joe

1 note

·

View note

Text

as someone who also does translyrics sometimes (occasionally, on a very amateurish level) yeah i share the sentiment. i noticed this most on their english translation of yuusha. it definitely takes a lot of effort to match the vowels exactly, and i can applaud that, but it just feels wrong. these structures weren't really made for english, so if you haven't listened to the japanese version, the way the lyrics are structured just feels off for english? like, just look:

Many days tinted in fairy tale scenes Have arrived at the end, proof we have seen I cut out and choose from a trip so long A little passage I review Tale of what's taken place right on this field Shadows of manifested pain and woe There was a hero who took out all foes A little-journey memory with you

now i'm not gonna lie, they did a pretty good job matching the word stress and the strong beats. sometimes the beat lands in an unideal spot, but that happens all the time in translyrics. but there's already a sense of unease i'm getting from the way they wrote the lines here. in the 3rd and 4th lines, "passage" gets two predicates, one before and one after (either that, or the 3rd line just doesn't have an object, which isn't right for "cut out"). the 5th line has a lot of padding, and the 7th line has this weird tone clash between the informal "took out" and the dramatic "foes". it's worth sacrificing a bit of vowel matching to allow for a more flexible use of language and bring out the best words you can

another important thing here (which yumi has mentioned) is the rhyme scheme. a lot of japanese songs simply don't have standard rhyme schemes because:

1) they use a 5-vowel system, unlike english's "5-vowel system" which actually has 20 vowel sounds (it gets to a point where there are some jp songs which abuse this fact by making lyrics that repeat the exact same vowel patterns over long periods. it's crazy)

2) they use a syllabary instead of an alphabet so every single utterance ends with a vowel (with the exception of n, but consonants are a lot less important than vowels in rhyming anyway)

3) their language is head-final, which puts the basic structure at the end, and since there are often grammatical rules for what sounds come at the end based on tense and stuff, a lot of sentences with similar structures and contexts end up rhyming anyway

so a lot of rhyme schemes in japanese music are pretty much just emergent and coincidental, and the one for yuusha's first verse ends up being AABCADDC. they replicate this in the english version, but since english has so many more vowels it feels shaky and structurally unsound. it would've been best to modify the vowels to have a more standard rhyme scheme (as well as internal rhyme schemes if possible) that flows well with the music, rather than try to stick to japanese's more liberal scheme that really only works for a specific kind of language that english is not. as yumi said, this mostly works for the ppl who have already listened to the jp version and are looking for a similar experience, even if it comes at the expense of the irregularities that this brings

(an example of this kind of switching up prosodic patterns comes in the form of the alexandrine, which has multiple versions across different languages from the original french alexandrine. french prosodic stress always comes at the end of a sentence, so french alexandrines (at least, the classic ones) only put stress at the end. in english, prosodic stress can be pretty much anywhere, so english alexandrines are pretty much just iambic hexameter. spanish alexandrines have 7 syllables per part instead of 6, with the stress at the penultimate syllable, because a lot of spanish words have penultimate stresses. there are more in the link)

tl;dr the way japanese lyrical writing works doesn't work that well for english lyrical writing (and more generally translating lyrics comes with structure clashes), so switching it up is often the best choice for translyricization

i just learned about the official english version of Racing into the Night and i am so fucking baffled, i've never seen anyone do anything like this, what the FUCK

#i've had this on my mind for a long time#glad to have a chance to let it out#no i won't be posting any translyrics on tumblr in the foreseeable future. they're pretty meh. i have the eyes but not the mouth

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

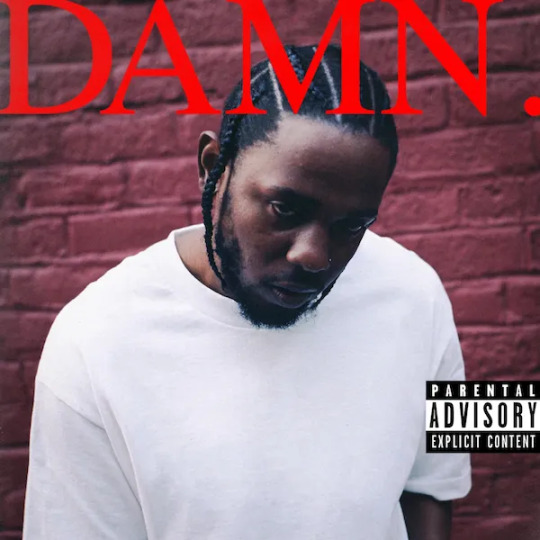

IN DEPTH REVIEW- DAMN Part III

I took a break from this series for March (Women’s History Month) and then had a surge of other projects to listen to in April. But I’m back with an in depth review DAMN, specifically two sister tracks, “PRIDE” and “HUMBLE”.

These two tracks address Kendrick wrestling pride. One side of the coin has him hating his temptation to feed into pride and embrace those emotions. The other side has him proudly bragging about himself and establishing others as below him. I mentioned in a previous review this album has a bipolar aura, and there’s no better example than these two tracks that have him accepting and rejecting this biblical sin.

PRIDE

“PRIDE” continues the mellow sound of the previous track “LOYALTY”. We hear a vocal of Bekon stating “Love’s gonna get you killed. But pride’s gonna be the death of you and me” with “you and me” echoing into the transition to the change in instrumental. Then we hear the chorus where Kendrick and guest singer Steve Lacy state they weren’t taught to share or care, but in a perfect world they definitely would. Then we get a couple of verses where Kendrick discusses his conflict between embracing or rejecting pride. He discusses the role pride has in his music, fame, relationships, and social status.

The instrumental is one of the most dreary on the album. The moaning inflections give an angelic yet sad aura throughout the song. Like even the lighthearted, supernatural forces see this conflict as unsolvable and depressing. Kendrick’s duality is also expressed by his voice gradients of high pitched to low pitch.

You can feel Kendrick’s internal conflict regarding pride. Continuing the biblical themes of this project, especially a common visited idea of fearing futility in avoiding damnation. He mentions several times how he would have less pride in a perfect world, but since a perfect world is impossible, he’s navigating being the best person in an environment that fosters the worst. An interesting concept he explores in this track is “faking humble”. He embraces the fact he is one of the best rappers today, and arguably one of the best ever. Pretending he isn’t wouldn’t be humble, it would just be dishonest. Yet, he feels conflicting in taking pride in his status while acknowledging it is accurate and well earned. He complicates this sentiment into an unsolvable problem. That carries into the next song.

HUMBLE

“HUMBLE” completely counters the sentiments of the previous track. Kendrick unwaveringly boasts about himself. He talks about how he could murk somebody without the influence of drugs and alcohol. He is real while others fabricate. He has unparalleled connections to influential people. And ultimately has bragging rights, an ironic take on a song called “HUMBLE”. But, I’m 100% sure this was intentional.

The production on this record was mind boggling as well. We hear a very hasty “nobody pray for me” which usually indicates a more chaotic cut off this record. And the super dark piano melody intensified this track. The music video is also something to behold; I could make a whole separate post just analyzing the music video.

For a song boasting at this magnitude, one would think it would be difficult to reach any kind of lyrical complexity. But Kendrick still delivers plenty of lines that took multiple listens just to fully comprehend what he’s saying as well as the layers beneath it. My favorite of this are the first four lines in the first verse.

“Ayy, I remember syrup sandwiches and crime allowances

Finesse a n**** with some counterfeits, but now I'm countin’ this

Parmesan where my accountant lives, in fact I'm downin' this

Dusse with my boo bae tastes like Kool-Aid for the analysts”

I had to listen to these lines at least 5 times to figure out what all this means. But I finally was able to make sense of it all. First, the sentence structure is broken to create the rhyme and syllable scheme. So to understand better, it might be easier to read it in a sentence/paragraph structure.

“I remember syrup sandwiches and crime allowances, finesse a n**** with some counterfeits.

But now I'm countin’ this parmesan where my accountant lives.

In fact I'm downin' this Dusse with my boo bae, tastes like Kool-Aid for the analysts”

Here we get a brief narrative telling the origin story of Kendrick compared to where he is today. He went from poor food (syrup sandwiches), and earning money from counterfeiting and crime, to counting Parmesan (aka cheese aka slang for money) with his accountant. To further the point, he mentions he’s drinking Dusse with his “boo bae”. Dusse, an expensive cognac, is often referred to in hip hop to reflect wealth and high status. The last line changes from a narrative to a commentary on analysts and critics. “Dusse with my boo bae tastes like Kool Aid for the analysts”. This line suggests that analysts drink Dusse and treat it like Kool AId. Metaphorically speaking.

Analysts will receive a very layered, complex, high quality message from Kendrick yet they summarize it as promoting violence and brutality. This idea was explored in the end of “BLOOD” with the fox news criticizing Kendrick Lamar for his lyrics on “Alright” off To Pimp A Butterfly. They generalized his sound and music as negative propaganda. It isn’t a coincidence that he used Dusse and Kool Aid as the drinks in the metaphor since both are associated with the black community. Someone who is stereotypical or racist may unjustly associate Kool Aid with people of color.

I read another analysis that stated the usage of Kool Aid refers to the well known phrase in the black community “all in the Kool Aid and don’t know the flavor”. Basically meaning forming an opinion or judgement without being aware of the full context your passing judgement upon. This analysis makes sense, especially in the context of these lines. Kendrick gives a story of where he’s coming from and analysts make judgement without knowing his past. I don’t take credit for this analysis, but I agree with it.

“HUMBLE” is a very intense track. And I only analyzed four of the many lines in this record. This entire album is layered and littered with messages. This track matches that energy. As Kendrick put it:

“There’s levels to it, you and I know. B**** be, humble”

Part IV Coming Soon

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Falling In Love Is Easy, Dealing With It Isn't

Tick tock. Tick tock. Tick tock.

The constant ticking of the clock was usually soothing as it was a constant, now it served as a frustrating distraction. With a flick of my wrist, it broke. No one cared for it anyway.

Rubbing my face through the disappointment of this morning didn't help as I wondered why words were absent from my mind. Every language in the world seemed to be extracted from my mind. Enochian included.

This needed to be addressed, the sorrow in his eyes, the obvious comparison to others and ridiculous belief he isn't enough, I hated seeing it. If one of us didn't hold up to the other it was me, I am not enough, Sam is well worth more than I ever will be.

Being this distracted almost made me miss the soft footsteps that were Jack joining me.

He came behind me with a hug, and I could tell he was expecting one from both Sam and me.

"Hey, Father. Where's Dad?" It was unusual for Sam and me to be separated since we've confessed our feelings for each other. Something that didn't come to my attention until I realized how much I currently missed him.

I patted Jack's arm, looked at him and set my pen, paper aside. "He's on a beer run. At least that's what he told Dean, I believe he's also getting some vegetables since your recent intake on candy has increased. Did Dean sneak you that candy?" I asked pointing to where he attempted to hide a bag of nougat. The flush on his face told me enough. I'll let Sam deal with Dean.

"No... So what are you doing?" Whether or not he's biologically mine, he lies terribly like me.

I handed him the rough drafts I had started but couldn't finish. None of them felt true, no matter how beautiful they sounded. "Poetry. From sonnets, odes, lyric, free verse, rhymed, to ballads. None of them are what I want." I sighed and looked at the mess surrounding me. Why was this task so difficult?

"I don't understand, they're well written. What's the problem?"

"That's the problem. They're all well written but meaningless. They don't capture how I really feel about Sam. No fourteen lines with ten syllables in each line are going to get all my emotions for him." Defeated and slumped in my chair, I wanted to cry. The only thing that kept my head up was the hand the was hiding my face. Why is this so difficult?

Jack was staring at me before he sat down next to me. "Then don't."

I looked up surprised, "Don't what?" He gestured to the poetry.

"Don't write a sonnet or a ballad, write from the heart. Isn't that what it's about? Not the form but the meaning?" He asked hands on the table, I nodded. Have I gone about this all wrong?

"Thank you, Jack. I think I got an idea." The pen I grew a hatred for as well as the paper, I apologized as I began to write.

My frustrations dissipated as the words filled my paper. I would describe it as talking rather than writing, I did mutter through parts where I became beat until I changed tactics.

Hours flew by as I wrote and rewrote this poem, it was vulnerable. Perhaps it didn't have the imagery or repetitive nature as the others before; however, the honesty it held outdid any flow from the other poems before.

In the end, at the last line, I stared. I've changed it twenty times already. I wasn't sure if it was my attempt at procrastination or if I simply didn't like it.

Sam had checked in with me when he got back hours ago, I begged him to not look quite yet. He's managed to keep to his promise even though I've seen him pop in to see if I had finished.

This is why it was no surprise to me he's attempting to stroll past me in a casual manner but is failing miserably.

"Love?" I called out and he stopped his "stroll" and was acting as if he wasn't excited that I was finally calling out to him. He's adorable.

He held onto the back of my chair, towering over and his eyes scanned the perimeter before focusing on me. "Yes?" I motioned for him to come closer.

When he did I plopped him down on my lap. Often it's the other way around, but I enjoy this way more than the other.

I smiled at the bounce of his hair, and the fact that he immediately embraced me into a hug which turned into a kiss.

There was an unspoken "I love you" that we held onto for a moment, it took me a moment to remember I had a surprise for him.

"Normally, I have no problem telling you how I feel. I don't know why this is different, but it is. I have a poem for you to read. I would like it if you could read it out loud. If you don't want to, that's understandable." I brushed Sam's hair out of his face as he nodded. It was difficult for me to reach over to the table and hand it to him, there was a built-up fear that I needed to push away.

Sam got a bit more comfortable on my lap and gave me a quick reassuring kiss before beginning,

"You deserve more than a sonnet

Or a loose free verse poem.

What I wish to bestow is theatrical,

To draw you with beautiful imagery,

Reel in emotions by deeper meanings,

Use a repetitive language as proof,

Whether it's synonyms, antonyms, metaphors, or smilies."

I saw his amusement at this is what I considered to be theatrical, and it was. I set my head into the crook of his shoulder. He continued on,

"Ignorance is to believe it would mean anything.

That I can pour my heart out in fourteen lines,

Perhaps about nature or humanity...

Not you, not when I want to tell you everything and more.

It would take me millenniums upon millenniums to perfect it.

And even then I wouldn’t be satisfied,

No rhyme scheme can help show how devoted I’ve become to you."

There was a slight shake to his hands. I could see he was trying to remain neutral but his facade was breaking with emotion. He had to clear his throat to continue. I closed my eyes and focused on his silky voice.

"Rhymed poetry or an ode,

A tune of a ballad or one of a lyrical poem,

How much more delightful my words would be,

Praising you in rhymes and lines of fours,

But it would deprive you of the trueness of my words.

Beneath the soft-sounding words,

The layers of beauty woven through imagery,"

I couldn't help but think Sam reading this made it sound beautiful, it was his voice and tone that made that so. I wanted to tell him that but I didn't. If I did he wouldn't finish reading the poem. Instead, I ignored the shaking emotion that was reeling off of him and focused on the words.

"Love is a mere word without meaning.

Trust, kindness, integrity, wisdom, patience,

These are what I’ve come to associate with you.

Love is an empty word to me,

Simply because it doesn’t describe anything,

I know I’ve fallen for you, my broken wings are proof enough,

Yet, the word love isn’t enough."

I could read the guilt that was rising and brought him closer to my chest, shushing away some of it away. I wanted to do more but knew to remain put. If I opened my eyes I would've lost control and kissed away his guilt, I closed them tighter.

"How does it describe the ease in my heart with you,

Or the tender moments that fleet faster than the light of speed,

The gentle kisses that I cherish more than air?

My wishes of peace for you go beyond our physical beings,

Existing is overwhelming with you,

The thought of the sun rising without you,

Words don’t belong to the anguish I feel."

His voice and breath were shaky and hesitant as he spoke. It pained me to be the one who made him feel that way, I had to remember it's not hurting him, it's overwhelming him. He needs to hear these words, he needs to see his worth.

"Dreadful days are imminent and groundless.

Death has no hold on me, merely the empty does.

Fear is an abandoned promise no one can hold against me,

Yet, here I weep from it at the thought of Death coming for you.

god is cruel to create such a being and make them human,

Simply another shameful act of his he couldn’t part within his rewrites.

his death and executor will be celebrated, praised, his wrongdoings won't be forgiven."

He let out an empty, hollow laugh at the mention of my father. I knew he didn't believe many of those lines but wouldn't invalidate them knowing they feel honest and true to me.

"Endlessly, I am grateful that you humor me.

Claim to love me as I do you, and more than I can know,

How you’ve come to forgive my multitudinous strings of mistakes and grievances,

Understanding will never come, not as it came to love you.

It’s troubling how much you swear upon god that you’re a stain to his creation,

Blind to see you’re a saint, and he is the hindrance to his work,

The only prayer I’ve sent to him is thanks for leading me to you."

He reached for my hand, and I nearly broke and swept him up into another hug at the feel of his hands shaking in my own. The emotion that was rolling off of him was drowning me into a stream of strange guilt. Seven more lines. I can comfort him after the last seven lines.

"I hope you listen, my partner, my love, my human, my Sam.

As I’ve cried to you before, nothing is worth losing you,

Everything is worth sacrificing to keep you here with or without me.

I’ve been lost since I was created, I would still be if it weren’t for the pain,

I was lost until I took on your pain, it isn’t just a claim,

But a truth I live with as I carry on through your wisdom.

Sam, my human, my love, my partner, love is empty, you make it full."

As the last word was uttered, I could feel Sam fall apart. The tears he had forced away broke into a sob while I wrapped him into my arms. I had to avoid apologizing knowing it isn't what he needs.

I couldn't think as I tried to blink away my tears, it stung to see Sam cry, it was complete agony to be the cause of it.

Sam turned himself to face me, straddling my lap, he was trying to calm himself down as he cupped my face. I couldn't ignore the quiver on his lips as he brought ours together.

I melted into it just as I do any other time, but this one felt different as I tried to hold him close. It was as if neither wanted to let go of the other. I couldn't help but keep my hands on his face and let him control the kiss.

He was chanting my name in between small breaks of our lips, the love he poured into his voice and kiss was more than overwhelming. I felt like I was drowning before, I knew I was now.

When Sam pulled away he gave me a sad smile as he wiped away my tears. He was still trembling.

"I can't- I can't tell begin you how I feel..." He was biting the inside of his mouth to avoid crying, even more, making more tears flow out onto my face.

"I- I love you, it hurts- it physically hurts how much I love you." He said and tore his eyes away as he tried to get his feelings in order, I reached for his hands and cradled them.

"You force me to see things I don't like to see, such as me being "worthy." You- you make me happy in ways no one else can, and I feel like loving you is such a privilege." The honesty in his eyes was powerful, I wanted to assure him that I felt the same way. I didn't say anything, I could see it in his eyes he already knew.

"I wish I could write my feelings or be more articulate as I say this, but Cas I can't. It's difficult to say you mean everything to me. That I fell for you and I'm more scared of losing you than I am of anything else." The tremble in his voice was still present, it was a small mercy that it wasn't as present as when he began.

"I don't know what I'm supposed to do when eventually we're pulled away from each other. How do you or me even begin to cope with that? I know you love me, and I wish you didn't. I wish you didn't care because it forces me to care. Because I see that when I'm hurt you suffer more than I do." This guilt he carries is conflicting in the sense I know he shouldn't have it, but it keeps him stable. While I want to take it away, I'm afraid of what would happen.

He pulled his hands out of mine to hold mine. He held them close to him as he cried, "I- I try for you- I really do Cas. I hope you see that I'm taking care of myself, I'm trying to see myself in the way you see me."

"I know, Sam. I know." It almost stayed stuck in my throat but I had to force it out. He had to know.

"And I know you've been trying for me." I didn't mean to freeze but I hadn't expected him to notice. I had hoped it would stay in the shadows and would remain unspoken, but it wasn't.

Sam got up and pulled me to my feet, he guided us to a couch where it'd be more accommodating to his height. I laid down first and Sam followed, I wrapped my arms around his waist and he held onto my hands.

Sam leaned into my touch and I could tell by his heartbeat that he was relaxed enough to fall asleep.

"Can we just stay like this? In silence?"

"Yes, of course, love."

#you guys don't know how happy i am that i finished this#this was one of my main projects and i finally finished it#hopefully it's well written i only got a couple of hours of sleep so I'm a bit tired#castiel#jack kline#sam winchester#samstiel#sastiel#sastiel fanfic

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

That Was How

I had this very nice request, and wrote it up. hello would a story about the bartender meeting the original c-137 rick be ok? Because i'm curious as to how she knew about him and the mind erasing so maybe some backstory?

Anon, I hope you’re still around. I enjoyed writing some backstory very much, and it ties in to some information in an older story called What Evil Lurks in the Heart of Rick.

SFW, Rick c-137/Bartender

⁂

You’d been working in this dive bar for a while now. Nothing fancy, nothing hip; just pulling taps and serving the occasional mixed drink if a tourist accidently wandered in. It was dark and smelled of old cigarettes from the time before smoking wasn’t allowed in public places. You were mostly content.

There were regulars who you knew by name. You liked your job, but some times, you got an itch to do something. Be something more. Your options were limited, however, so you didn’t.

“Hey. I think that guy’s pukin’ in the restroom,” Rob, one of the regulars who shuffled in after his shift so he didn’t have to go home and deal with his family, announced unnecessarily.

You had heard, and the retching from the restroom seemed amplified.

You groaned.

“I’ll give you a free beer to check on him,” you offered hopefully.

“You know you ain’t allowed to give out free beers!”

Frowning, you had to nod. The owner of the place had threatened to terminate you when he found out you’d occasionally given away product to the people who spent a lot of their time here. “They’ll pay for it,” he’d yelled. “Don’t give it away!”

Rob smiled drunkenly at you. “If you pay for another pint, I’ll go . . .”

Your salary didn’t allow you to be that altruistic.

“Never mind,” you sighed, wiping your hands on one of the towels under the bar. “I’ll go see how he is.”

Rob waved at you as you left your workspace. Walking to the establishment’s only restroom, the retching hadn’t stopped. You knocked on the door, lightly. “Hey. Hey. You okay in there?” you asked with your head near the crack between door and doorframe.

Your answer was another bout of retching and the unmistakable sound of liquids hitting the water in the toilet.

“At least he’s not pukin’ on the floor!” Rob called to you gleefully.

Thank heaven for small favors, you guessed. Out loud, you said, “You need help?”

There was a groan in response.

Steeling yourself, you grabbed the doorknob and found it wasn’t locked. Although you half-hoped it would be so maybe the guy inside would have the chance to right himself, at least you wouldn’t have to get out the toolkit and unscrew it to get in. You weren’t incredibly happy about barging in on a vomiting man--that was nowhere in your job description!--but having someone pass out and choke on their own puke wouldn’t be a great alternative either.

“I’m coming in,” you announced.

You followed through, and found the old lanky guy who’d stumbled into the bar earlier hugging the toilet. He’d filled the bowl with pure bile-colored liquid; in your experience you knew that meant he’d been taking in only alcohol for a while, with no food in his stomach to help absorb it.

He looked haggard and pale; his eyes bloodshot and sunken. He had strings of yellow drool dangling from his lower lip. When he picked his head up to look at you, he wiped the back of his forearm and hand across his chin, and managed to smear some of the drool into his hair. Before you could move further into the room, he lifted himself upward enough to vomit into the toilet bowl once more.

When he sat back down on the floor with a groan, some of his color had returned.

“Gotta purge that swill they call Plutonian vodka,” he croaked, as he gave you a weak smile and a wink.

That was how you met Rick Sanchez.

⁂

You’d helped him clean up a little after his little evacuation in the bar’s toilet by offering him actual cloth towels instead of the cheap paper ones available that disintegrated on contact with water. He wiped his face; you swallowed your gorge and wiped his hair. Then you held his arm to assist him back to a bar stool and gave him a glass of water.

He scowled at that and requested a shot of vodka, neat.

“N-n-none of that Plutonian shit!” he’d demanded, as if you acted like you even knew what the hell he was talking about.

Gently you nudged the glass of water closer to him. He stared you down; you stared back, and he finally took it, although he coughed through the first few swallows. Then he asked again for that shot of vodka, pretty please.

Rob looked like he was going to say something. Come to your defense, maybe? Recommend the guy get the hell out? Call the cops? But at the first syllable that tried to come of out his mouth, the old guy whipped around and scowled so hard at him Rob choked off whatever he had thought to say. You saw the new guy’s free arm tense, a little, and Rob glance down.

Your regular customer gulped and in a rush of movement, he pushed away from the bar and stammered he had to get home. He threw a handful of bills on the bar and was gone before you knew it.

The new guy watched him go with narrowed eyes. You had no idea what just happened or what Rob may have seen out of your line of sight on the other side of the bar. Once Rob was gone for good, he turned back to you with a wide smile.

“What’d’ya say, baby? Set me up a drink and I’ll buy you one too.”

You find this guy in the bathroom, puking his guts out, wipe vomit out of his hair; he does something to intimidate a regular patron of this place; and now he wants to buy you a drink? What was next, him crashing on your couch?

Yes. That’s exactly what happened next.

You took him up on his offer to have a single drink with him. He launched into a wild story about his life. None of it made much sense, but he didn’t seem the kind of crazy that was going to end up stabbing you; he seemed the kind of crazy that was full of fun and adventure. He had to be an author. No other person could com up with the outrageous stories he told you.

When he mentioned that he’d been drifting from place to place recently and was looking for somewhere to crash for the night, you did suggest your couch. With a smug grin like he’d been waiting for you to offer, he took you up on it.

That was how Rick Sanchez came into your life.

⁂

He wandered in and out of your life randomly. He’d show up at the bar. Occasionally you found him snoring on your couch when you came home. There was never any rhyme or reason to when he would arrive, and he sometimes just disappeared again without explanation either.

Once, when you pinned him down enough to at least have breakfast with you, you mentioned you’d love to read one of his books sometime.

“Books?” he replied, completely baffled.

“Yeah. Can you give me a title or two?”

With his forkful of pancakes halfway to his mouth, he frowned. “I don’t know what the-what the fuck you’re talking about.”

“Your books!” you said in exasperation, as if repeating it was going to make it clear. “All these stories you’re telling me? About different planets and different booze and the interdimensional travel--you have the whole world-building down to an art! Is it like a series or are there standalone novels? Tell me where to start, I can’t wait to read them!”

Rick set his food back onto his plate in a deliberate motion.

“You think that I-I-I am making up everything I’m telling you?” he said in a low, even voice.

You’d never seen him so serious, but you laughed anyway. “Yes! Of course!”

He scowled.

“You’re an idiot,” he announced, and reaching over the table, he grabbed your wrist and dragged you to your feet.

As you cried out in scared protest, Rick pulled a device from the inside of his lab coat and from it, produced a swirling green and yellow circle of opaque light. Ignoring your fright and confusion, he pulled you through it into another world.

That was how your adventures with Rick Sanchez started.

⁂

His visits were still erratic, but when he did deign to take you with him, he showed you things you couldn’t have imagined. Rick was your guide from one end of the galaxy to the next; he escorted you into new dimensions filled with wonder and horror. You visited with unique people living nothing like you’d ever seen. You saw worlds that were nothing like anything on Earth.

You drank with Rick at a hundred different alien bars. You accompanied him to places he had to do ‘business’. Although full of contempt that you were such a tourist and a rube, he introduced you to so much more than your entire life could have been.

You discovered that your life was not even a speck of dust in the scheme of the universe, but instead of being crushed by the knowledge, you only wanted to learn and see more.

You’d become conditioned to get excited at the sound of a portal. You looked forward to seeing his unruly blue hair and boney build. You imagined what it would be like to hug him. You had dreams about what it would be like to be naked with him, in your bed.

That was how you fell in love with Rick Sanchez.

⁂

When you realized that you had deeper feelings for him, you were giddy and nervous and moonstruck. You’d never imagined yourself with an older man; you’d never imagined yourself meeting someone in such a random way who would mean so much to you.

You were just being silly, weren’t you? You couldn’t have fallen in love with this guy who just showed up out of nowhere. Right? It was just the thrill of going on adventures. It was just the idea that he singled you out. Right?! There was no way you were thinking about a serious relationship with him!

The two of you hadn’t slept together. You hadn’t even shared a bed; every time he crashed at your place he passed out on your couch! You’d never had a kiss, never had any intimate touching unless you counted when you held his elbow to help him out of the restroom at the bar. Rick had never brought up anything of the sort; in fact he scoffed and derided any couple you happened to see on your travels. You’d heard his rant about ‘relationships’ and ‘biological need to breed’ more than once.

But you couldn’t deny that you got a thrill in your stomach whenever he showed up. You knew you were flushed around him, you could feel the heat in your cheeks and your palms felt damp. Sometimes it was hard to hear what he was saying over your pulse pounding in your ears, and the times you were close enough to smell him, it was intoxicating.

You knew he wasn’t celibate. You hoped he wasn’t celibate! Firmly you told yourself the next time he showed up, wanting a place to sleep for the night, you were going to take him to bed. You were going to show him what you thought of him. You were going to give him the best sex of his life!

When he did arrive--unannounced, as usual--at your small apartment two weeks later, he was harried. He was preoccupied and anxious. None of those three things were anything you’d associate with Rick.

Still, you gave him the drink he asked for and, steeling yourself, you told him you wanted to talk to him about something important.

He downed the tumbler of vodka you’d handed him, belched, and took your hand.

“No-no, I’ve got to, I’ve got to--there’s something I have t-to tell you first, baby,” he said.

His touch made butterflies float in your stomach; his words tied them up in knots.

“This is impor-important,” he insisted. “I should’ve told you this a long time ago.”

Your breath caught in your throat. You were glad you opted for a matching, lacy bra and panty set today, because you couldn’t wait for Rick to see you in them, and then for his large hands to strip them from you.

“I’m in big trouble,” Rick continued feverishly, “and I think you are too.”

With no further explanation, he opened a portal and took you someplace new.

It was an apartment. It was only slightly bigger than the one you’d left, and maybe slightly nicer. You looked around, wondering if this was his place finally.

“I hope this is okay. I think it’ll be okay,” he said.

“What?”

Rick waved off your question. “I’ve paid for it, but there’s a monthly fee, like a home owner’s fee you’ll have to cover. There’s amenities like a pool and shit on the first floor, and a grocer’s and stuff nearby. It’ll be perfect for you.”

“Rick, what are you talking about?”

“I got you some clothes and stuff too. In the cl-closet. And extra towels and sheets. I know you like the heavy sheets with the high thread count. I snooped around your place. I know how creepy that sounds.”

None of this made any sense, and your arousal was starting to sour to fear. “Rick--?”

“Come on, I-I-I’ve got something else to show you.”

Before you could protest, he pulled your through another portal.

You stepped out onto a rocky plateau. You could breathe, but the atmosphere was thin because the stars in the sky were crystal clear and it was almost too cold. There was no vegetation. Straining your eyes, you could see the edge of it as well. This wasn’t even a planetoid, this was a desolate chunk of rock drifting through space.

You realized you could see your shadow blinking on and off from a yellow light behind you. Turning, you saw a single building with a flashing neon sign. The words were written in an alien language, but as you stared at them, they started to morph into something you could read.

Before you could fully make them out, however, Rick took your shoulders and turned you to him.

“I am so sorry, baby,” he said, and he sounded genuinely upset. “The Feds are after me. They got pretty fucking close this time--”

“The Feds?” you interrupted, your gaze inadvertently drawn back to the sign you could almost read now.

“The Galactic Federation!” he said angrily, but that didn’t actually explain anything. “They’re hot on my goddamn tail, and I’m going to have to lay low to shake them off.”

His barely controlled panic finally, really, caught your attention. “What do you mean? What are you talking about, Rick?”

“I’m going to have to live with my family,” he replied, as if that made any sense either. “That’ll keep me safe. But I think you’ve been seen with me, so you may be under surveillance--you might be taken and questioned about me, and that-that . . . that just can’t happen. The apartment? It’s yours now. They don’t know about it. You should be safe there. And this place? It’s neutral. It’s outside the Federation. I put in a good word for you. I think you’ll like it.”

Unbidden, tears formed in your eyes. “Rick, I don’t understand what you’re saying!”

For the first time since you’d met him, Rick looked remorseful. “I’m sorry, baby.”

From his inside pocket, where he kept his portal gun, he extracted a new device. It was larger and unwieldy, and looked held together with zip ties and some duct tape. He pointed it at you, told you he was sorry again even as you begged him to give you real answers, even as you told him you didn’t care what kind of trouble he was in, you just wanted to be with him, that you thought you loved him, no, please, Rick, please--and you were blinded by a white light as he pulled the trigger.

The world went blank.

When you were finally able to see again, an old man in a lab coat was standing over you, cursing at some unknown piece of equipment in his hand that was smoking and throwing sparks randomly.

“Fucking prototype!” he cursed. “Goddamn piece of shit, falling apart when the fucking trigger was pulled--”

You groaned.

The sound you made drew his attention to you.

“Oh, hey, you okay?” he asked. He sounded like he was feigning concern. “That was some tumble you took!”

He offered you a hand, which you accepted. A tiny thrill nestled in your belly as you stood, but you also felt dizzy. His hand was cool and dry, and even upright, he was much taller than you. His hair was wild spikes of blue, and he wiped a bit of drool off his lower lip. There was an itch in your brain, like some part of you recognized him.

“Do I know you?” you asked, puzzled.

His eyes shifted away from you. “Uh, n-no. Nope! I just happened by when you fell. Here, this key fell out of your pocket. Looks like an apartment key? I had one like that once. The button on top gets you home.”

You accepted it. It did look like a key to a door, and you had to just nod about the button, because there didn’t seem to be any other way to get off this rock.

“And, uh. You said you had an interview. At the Bar?” he continued, waving a hand at the building.

You looked to where he indicated. “The Bar At The End of The Universe”, the yellow neon sign flashed on its roof.

“Yeah, I guess,” you agreed slowly. You must have hit your head when you fell, because everything was a little blank, but that had to be right. Why else would you be here?

“Well, good luck!” he said, giving you a little push and a nod. A strained smile stretched his face.

“Yeah, okay, thanks.”

You started off towards the door. You had the unmistakable feeling that he was watching you go. When you turned around, you were right.

Still puzzled, you called, “Are you sure I don’t know you?”

The smile, as forced as it was, faded from his face. He looked upset and guilty, but you had no idea why that would be. He just looked so familiar, but he replied quietly,

“No, baby, you don’t know me.”

With that, he waved you on. You studied him a moment more, sure you’d seen him somewhere else, but finally felt awkward enough that you continued to the Bar. You opened the door and walked inside, immediately greeted by a four-armed bouncer who asked your age. Telling him you were here for an interview, he looked you over and directed you to the management.

“We are looking for a new bartender!” you were told. “Rick c-137 put in a good word for you!”

“Rick . . .?” you whispered, mostly to yourself.

“Oh, don’t worry,” you were assured. “He doesn’t come here very often. We get lots of other . . . guests, though.”

The staff who were standing around snickered at that, but you figured that since this was a watering hole for all sorts of aliens, it didn’t mean much.

“With that recommendation, and if you want the job, it’s yours.”

There was a niggling in the back of your mind about this “Rick c-137”, like there was something just out of memory’s reach, but that was neither here nor there at the moment. You warmed to this. You needed a job, and you knew you could bartend, so why not someplace like this?

“I’m Yvonne,” you said, smiling and offering a hand to shake. “People call me You.”

That was how you got a job at The Bar At the End of the Universe.

fin.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

@theunitofcaring asked me to post more translation comparisons, and since I love her and also mocking bad poetry from the 1850s, I am only too happy to oblige. In any case, it gives me an excuse to talk about Ein Gleiches (Another one like it, in reference to its companion, Wanderer’s NIght Song). Goethe isn’t my favorite German poet, but this may be my favorite German poem, and certainly a contender for my favorite poem written in any language. (I’m not alone here; it’s probably cited more than anything else as the most perfect example of German lyric). Here it is in the original:

Über allen Gipfeln Ist Ruh, In allen Wipfeln Spürest du Kaum einen Hauch; Die Vögelein schweigen im Walde. Warte nur, balde, Ruhest du auch.

And here’s a literal translation: “Above all the summits / is rest, / in all tree-tops / you feel / hardly a breath; / the little birds are silent in the wood. / Only wait, soon, / you will rest too.”

Ein Gleiches is very easy to translate, and almost impossible to translate well. There’s no repetition, no embellishment, nothing. Everything in it is necessary. There’s a distinct rhyme scheme, but it’s also formless in a way that almost reminds me of Hölderlin. The effect is poetic while still being completely natural. At no point does it sound like the poet is trying to create an effect or fit a constraint; he doesn’t have to. It just flows.

In German, the whole poem is twenty-four words long.

The most famous, and probably still the best, English translation was written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1845:

Over all the hilltops Is quiet now. In all the treetops Hearest thou Hardly a breath. The birds are asleep in the trees, Wait, soon like these, Thou, too, shalt rest.

There’s a lot that Longfellow gets right. He doesn’t add anything. It rhymes, the general structure is the same, and, more importantly, the last line has that same sense of finality, of positive darkness, the ambiguity of sleep and death. This line is the key to the poem: it’s only after reading it that the other images slot into place and make sense as a unified whole. I spent much more time on it than any other part of my translation. “Thou, too, shalt rest” isn’t as light as “Ruhest du auch,” which is practically an exhalation, but it feels right.

At the same time, the rest of the poem has some serious problems. “Over the hilltops / is quiet now” doesn’t quite work. It’s not immediately obvious that quiet is functioning as a noun, so it looks like an article is missing. “Hearest thou” might be a convention, but it’s still unforgivably affected in 1845. (Ein Gleiches might be the least affected poem every written). And while I don’t know what exactly is wrong with “the birds are asleep in the trees,” I do know that it just bugs me.

It’s still much better than the contemporary alternatives, like this 1844 translation by Theodore Martin:

Peace breathes along the shade Of every hill. The tree tops of the glade Are hushed and still. All woodland murmurs cease. The birds to rest within the brake are gone, Be patient, weary heart, anon Thou, too, shalt be at peace.

That’s forty-three words, for those of you keeping track, and it takes legitimate effort to make an English translation of a German poem longer than the original. Rest can’t simply exist above the mountains; it has to “breathe along the shade of every hill.” The tree-tops have gotten together and formed a glade, there are anons and weary hearts and a line about woodland murmurs that’s made up out of whole cloth. What’s worse, it’s obvious that all that added verbiage is there to make it rhyme. The original is effortless; this feels forced.

This is what happens when translators don’t think about what makes their source text work. In this case, it isn’t the rhyme scheme, and sacrificing the poem’s minimalism to keep the rhyme just kills the effect. (As a nitpick, “the birds to rest within the brake are gone” is a super weird translation of “Die Vögelein schweigen im Walde.” They clearly aren’t gone, just quiet, which is necessary for the poem to make sense on a literal level. In what sense is the reader like them if they’re not currently resting?).

On the other hand, these two attempts (by Arthur Hugh Clough and R.A. Mowat, respectively) are an object lesson in not fucking with the rhyme scheme for no real reason:

Over every hill All is still; In no leaf of any tree Can you see The motion of a breath; Every bird has ceased its song. Wait; and thou too ere long Shalt be quiet, in death.

O’er the tops of the mountains is peace; In the trees scarce a breath stirs their crest; And the birds in the wood singing cease; Only wait – soon thou too shalt have rest.

I have nothing against Doppelreim in principle, but Clough just makes it sound sing-songy. “Tree/see” is particularly childish, especially juxtaposed with that absurd “ere long.” And the man’s obviously never heard of subtlety. (Shockingly, he’s not the only translator to give the game away by rhyming breath with death). Even so, I think Mowat is worse. I have no idea why he’s chosen to introduce a meter, when it only forces him to add more awkward and unnecessary syllables. Not to mention the inverted syntax, which I try to avoid as much as humanly possible. It’s even more sing-songy than the Clough translation, with none of Goethe’s suppleness or gravity.

(More terrible translations into various languages can be found here; they’re all bad for pretty much the same reasons. I particularly recommend the line “Scarcely by the zephyr / the trees / softly are pressed.”)

With all that in mind, here’s how I chose to translate it:

Above the mountains There is rest, And in the treetops Not a breath Of air is felt; In the wood, the little birds are still. Only wait, you will Soon rest as well.

In the end settling for slant-rhymes was the only way I could keep from it from seeming forced. I’m still not entirely happy with this, particularly the last line, but I’m satisfied with the general approach.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 2- Poetry

It’s not exactly finished, and a day late because I wasn’t home yesterday, but it shall be shared!

Roses are red,

Violets are blue.

You’re kinda cute,

But get out of my school.

I found the note in my backpack after school one day, the magenta paper starkly contrasting the blacks and whites of my school supplies. It was quite crumpled, the result of me shoving my books on top of it, but I could still make out the scribbled words.

ABCB rhyme scheme. Classic choice, although the 4-4-4-6 syllable pattern showed that this was not written by someone who didn’t know much about poetry. Or, it was someone trying to be extremely bold.

Either way, the poem was completely anonymous, so I had no idea how to actually figure it out.

“Hey, Miss Suave-Face, you still alive?” I called over to my twin sister, who was already lying on her bed as if she was already going to sleep. At two in the afternoon.

“I need the car today, Kelsi.” She stretched her arms up, answering a question that I didn’t even have.

“I’m not going out tonight, Jess, I need your help with something,” I said, walking over to her bed and dangling the note in her face. “This was in my backpack. I have absolutely no idea how I’m supposed to feel about it.”

“A note? Lemme see that.” Jess snatched the paper out of my hand, looking over it with the scrutiny of some forensic scientist, trying to will evidence out of thin air. “A love note? Aw, someone has a crush on my widdle sister.” She sat up, pinching my cheek as if I were six years younger than her, instead of six minutes.

“Knock it off,” I pushed her hand away, though I sat down on the edge of her bed, “what do I do though? I don’t, well, know who sent it, and uh, did you read the last line of that poem?”

“Of course I did!” Wearing a grin on her face, she sat up straight, before dramatically clearing her throat. “You have a lot to learn about how people display their crushes, young one. I will teach you in my ways, and in no time, we will actually get you a date for the prom.”

“This isn’t about the prom, this is about someone wanting me out of the school.” I crossed my arms, shifting over so I could lean against the wall.

“Because whoever, or is it whomever? Whatever. In short, they’re overwhelmed by your presence, and they don’t know what else to do.”

“So… they decide to be aggressive?”

“See? You’re already learning.” Jess patted my head, seeming way too excited with this whole thing. Maybe I shouldn’t have told her about the letter, but it was too late. “You, for example, express your crush on someone by turning beat-red if they ever get close to you, while others lash out because they’re embarrassed.”

“Did you have to mention that?” I said, turning red from the thought of my actions around my crushes. “I don’t need to be reminded of Kyle Young.”

“And Cassidy Jacobs, and Jackie Trejo, and John--”

“I get it, I’m dumb.” I grabbed one of the many pillows Jess kept on her bed, hitting her with it. “But, what do we do? How am I supposed to figure out who sent it?”

“Oh, leave that all to me,” Jess began, before her phone ringer went off. Picking it up, she examined it, squinting because she was out of contacts and refused to wear her glasses, before gasping and holding it close to her chest. “Oh my God, Helena apparently has some big news apparently, so, I’m going to talk to her real quick. And then we’ll get back to your situation.”

“Fine, just, don’t tell her about it, okay? You and your friends have already made a big enough deal about getting me a date to prom, I don’t need it to be more dramatic.” I started to get up, giving Jess the best puppy-eyes I could attempt to do.

“Okay, I won’t. Not yet, at least. They may provide to be valuable assets later.” She gave a smirk as she used her fancy words, mostly because most people at school thought she was the dumbest person alive. She wasn’t actually dumb, she just had ADD, and didn’t take her meds half of the time.

“I’ll be downstairs.” And with that, I walked back over to my bed, grabbed my black and white poetry notebook, and went downstairs to do some writing.

Crushes truly suck.

They’re like bugs on a windshield.

Too many at once.

Stupid little note.

Pink and telling me to leave.

Who the hell wrote it?

As I wrote poetry down in the living room, I found myself only being able to write about the dumb “love” note and the yuckiness that romance was. On other days, I would disagree with the latter part, but I wasn’t feeling romance that day. Like, it did flatter me that someone thought I was cute, but did they really have to ask me to leave?

Was being aggressive to your crush really that normal?

I threw down my notebook in defeat, knowing I wasn’t going to be able to write anything good that day, before walking to the little window nook we had in the living room.

[MAY BE CONTINUED, SOMEDAY]

0 notes

Text

A Potent, Little Metaphor

In the late 1980s, I wrote a musical called Attempting the Absurd, about a young man who has figured out he's only a character in a musical and doesn't actually exist, and that knowledge causes him lots of grief. Ultimately, he wins the day by producing the script for Attempting the Absurd. I recently published the script and vocal selections for the show on Amazon, and I described the show as "meta before meta was cool." But you know who did meta way before any of us? Gilbert and Sullivan. Their operettas frequently referred to themselves and occasionally to each other, and more than that, half their agenda was mocking the conventions of opera, as they used them. Since we did our public reading of The Zombies of Penzance in January, I've been reading books about Gilbert & Sullivan, and seeking out videos of their shows (I highly recommend anything from Opera Australia). I had seen some of their shows, but I'm discovering the others now as well.

And what I realize is that half the G&S agenda is mocking polite society, politics, and human nature; and the other half is writing operas that mock opera. Gilbert's lyrics mock opera (with wildly inverted sentences, overblown imagery), Sullivan's music mocks opera (the repetition, the bombast, the self-indulgence, and once in a while, forty notes to one syllable), and the two of them together mock opera's seriousness, it's pomposity, its faux exoticism. Gilbert and Sullivan "broke" old-fashioned opera. They laid bare the silly conventions and cliches by both using and abusing them all at the same time. In term's of today's musical theatre, we might call G&S shows neo musical comedies, in the language of opera. In fact, I think that's what I called Jerry Springer the Opera when we produced it. Writing The Zombies of Penzance was technically very hard for me, but it wasn't hard conceptually. I get G&S and I've been in love with The Pirates of Penzance since I saw Kevin Kline do it on Broadway in the early 1980s -- just a few years before I started writing Attempting the Absurd, now that I think about it. It was enormously fun getting into Gilbert's voice with this show. Writing the dialogue in his voice was a breeze, but writing lyrics in his style is insanely difficult. Here's one of my favorite moments of dialogue:

FREDERIC: Oh, would that you could render this extermination unnecessary by accompanying me back to civilization! No doubt the doctors and scientists have by now concocted an antidote, or failing that, they could cut all your heads off with a clean, sharp knife. KING: No, Frederic, no, no, no, that cannot be. I don’t think much of this tedious, soulless, shadow life we endure, but contrasted with the forty-hour work week, it is comparatively fulfilling. No, Frederic, I shall live and die – and then live again and likely die again – a Zombie King!

But Gilbert wrote some incredibly complex rhymes, and I'm pretty sure I kept every rhyme scheme he set up, interior rhymes and all. This is my rewrite of "Climbing Over Rocky Mountain."

We’re Christian girls on a Christian outing, No bad words and please, no shouting, Far away from male temptation carnal, Where our nethers never quiver, By the ever-throbbing river, Swollen where the summer rain Comes gushing forth; Gushing forth in spurts and sputters Sloshing through the roads and gutters, Pounding through the virgin hills below us. Scaling rough and rugged passes, Working out our shapely asses, There are greater joys, we know, in purity! Fit and healthy virgin lasses, Keeping pure our virgin asses, There are greater joys, we know…!

The one exception to my fidelity is in "Modern Era Zombie Killer," where I added one syllable to the title phrase though it still scans to the music correctly.

I am the very model of a modern-era zombie killer, I can cut off heads and yet be gentle as a caterpillar. Since the early days when the initial virus circulated, When you think of me, you think of walking dead decapitated. I’m very well acquainted, too, with matters metaphysical, I understand the issues, both the obvious and quizzical. If I could slaughter zombies, I would cross the River Styx for them. I’ve seen Romero’s movies and I’ve memorized all six of them! I like to make them suffer but I don’t think they can feel a lot; Decapitation’s fun, I know, but zombies really squeal a lot! In short, I can be fearsome or be gentle as a caterpillar; I hereby present myself, a modern-era zombie killer.

But I don't think I changed anything else (other than making it into a zombie story). Despite the wacky origin story, I want Zombies to be as authentic a G&S show as this fanboy can make it. But now as we're blocking the show, I realize, this is a really different kind of performance for the actors. There are so many songs and sections of songs in which the characters turn to the audience and explain the situation, their opinion of it, what they want, etc. Sometimes at great length. For musical theatre actors, that's so unnatural, to just stand and explain.

But as I think about it, I realize that's exactly what Threepenny does. Next to Normal does it a lot, also Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, High Fidelity, and so many other shows. Even Sweet Smell of Success, which we produced last season. In these shows, the actor has to be both (or alternately) inside the scene and outside the scene -- but still the character either way -- both narrating and living through the moment, both in the place and time of the story, but also aware of and talking to the audience. That's a hell of a tightrope. Also, like the original G&S show, we have a small stage and a relatively big cast, so staging is limited when everybody's onstage -- which is the last 10-15 minutes of both acts. I know being so physically static onstage for such a long time also feels weird to the actors. But having seen a lot of G&S shows now, they really do work this way. The music and text are so funny, and the plot is so insane, that the audience doesn't get bored in the least. The audience needs time to focus just on the words.

In fact, G&S shows usually follow a rule I learned from Hal Prince -- the more complex the content, the less active the scene should be physically. Think of brilliant musical theatre moments like "Being Alive," "The Ladies Who Lunch," "I'm Still Here," "Rose's Turn"... there's not a lot of movement, because there's so much going on emotionally, narratively, thematically. If we make the audience choose between visuals and content, they'll choose visuals. Humans are visual creatures. We have to make them choose content sometimes -- well, often in a G&S show. So our actors have all kinds of obstacles thrown at them this time. To find that neo musical comedy style, exaggerated, highly stylized, but still really honest -- that's not always easy (especially when you're playing an unusually high-functioning zombie). To find that reality that contains both the crazy inside world of our story and also our performance and audience. To get comfortable in the slow telescoping time of opera, even slower than musical theatre time. The scripts for musicals are much shorter than scripts for plays, because it takes longer to sing words than to speak them, because music operates on a different kind of time, a slower time. In musical theatre, actors learn to live inside those extended moments of time, fully alive but staying in that moment, that emotion, that reaction. Opera slows time down even more, because the music is even less in constant service of the storytelling. And Gilbert and Sullivan sometimes slow time down opera time even more than that, to mock the repetition and narrative pace of opera. Mabel's first entrance in Pirates/Zombies is one example. So are both act finales. So the challenge for our actors is to create an interesting performance not in physical zombie shtick as much as in character, reaction, backstory, social context, and our wonderfully absurd set of circumstances. The idea of zombies eating, then marrying these girls has to seem to be a Very Serious Matter Altogether. 'Cause really, are marriage-friendly zombies any more ridiculous than man-eating flytraps? The secret to Little Shop is for the actors to take it totally seriously, to believe that Audrey II is a genuine threat. The material takes care of the funny. It's the same for us. But our guys are playing zombies, after all. They have to be recognizably zombies. Zombies who sing operetta, including patter songs. Even though they can't walk very well. Because, did I mention, they're zombies.

All this reminds me of a great, weird show we produced called Bukowsical. The central joke of the show is that it tells the dark, ugly, cynical life story of the brilliant American writer Charles Bukowski, but in the most inappropriate form possible, a cheery, colorful, upbeat musical comedy. And that's essentially what The Zombies of Penzance is. It's a horror story told in the most inappropriate form possible, a bouncy, dry-humoured British comic opera. And that wrongness, the frequent self-reference, the mismatch of form and content, and the constant violations of period (even though we're pretending this was written in 1878) are all part of the meta joke.

My zombie hunting habits, though a potent, little metaphor, Are really more subversive than the critics give me credit for. In nineteenth cent’ry operetta, comedy or thriller, I am still the very model of a modern-era zombie killer!

We're telling the audience Gilbert and Sullivan wrote Zombies in 1878, but as you watch the show, we're constantly reminding you that Gilbert couldn't have possibly written these references to movies, to George Romero, to Pepto Bismal or the Aqua Teen Hunger Force, and he certainly never would have used the word fuck, which our show does a few times.

The fact that I rewrote Pirates as Zombies, and then concocted a ridiculously meta origin story, means it's a meta meta musical. It was already self-aware as Pirates, but now The Zombies of Penzance carries with it, every second, an awareness of Pirates, and for people who know Pirates well, there's even more fun to be had there, in how close to the original my "translation" often is. Meanwhile, our actors will find their way. They always do. We often do shows that are just so weird or so unique in their particular rules that it takes the actors a while to figure out how it all ticks and how they fit into that clockwork. Luckily, they all trust me, so I just keep moving forward and they keep lumbering along beside me. So much fun ahead. The adventure continues. Long Live the Musical! Scott from The Bad Boy of Musical Theatre http://newlinetheatre.blogspot.com/2018/08/a-potent-little-metaphor.html

0 notes

Text

“Badlands (Deluxe Edition)” - Halsey

My attempt to review Halsey taught me that I’m actually a bitter, solipsistic old man. Read this absurd mess at your own risk, I honestly can’t believe I spent as much time on this as I did.

I want to like Halsey - I really do. It would be a wonderful fuck-you to the very idea of pop critic “tastefulness” as well as a raspberry in the face of the folk-rock pastorality that maintains a strong grip on the charts. And music aside, she’s championed LGBT rights and recently donated a large amount of money to Planned Parenthood in the face of its funding being cut; admirable political stances, for sure.

Of course, I’m well aware that wanting to like art-as-art simply because of the politics of the artist is often a poor motivation for enjoyment. And despite what fans may consider to be a “radical” image, Halsey remains 100% pop and the object here is still enjoyment. So the big questions here are: can I admire her music? And if I can, can I also enjoy it?

I make this distinction between admiration and enjoyment mainly because my initial negative reactions to Halsey have provoked some to point out that as pop product, she is not “made for me”, “me” being a 22-year-old generally-male-identified person. On one hand, this is true. On the other, I’m not sure if that means as much as it seems to; who’s to say we can’t enjoy music that’s not “made for us”? Isn’t that a great test of whether or not pop music works as mass entertainment, if it can somehow sweep outside the boundaries of its “target audience” and catch unlikely fans with an appreciative ear for craft? Sure, it’s not the only test, but we should admit to ourselves that there’s something particularly impressive about an artist who clearly has the artistic capability and reach to draw a bigger crowd, but is also committed to delivering their own personal message to a specific group likely to identify most with them.

And yet it seems there may be two main types of artists that fall into this category: those pop-focused, who intend to catch wider audiences than the targeted, and those politically-motivated, who actively push out parts of the wider audience to focus on a smaller group. Both, if craft is sufficient, end up attracting a wider audience, and I will provide examples to help clarify the effects: the former type is probably well-exemplified by a pop star like Britney Spears, or a country-pop star like Miranda Lambert. I doubt that either of these artists intend to target someone like me in their initial marketing, but since I can appreciate the production/songcraft/performance, I end up liking it anyway. All the better for them - more fans = more profit (or at least one would hope, though our current music industry seems to ruin even this basic axiom).