#aslnotes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

i LOVE that youre using asl gloss for frisk!

I’m glad that you’re happy, but mine is still really clunky and would probably make a fluent speaker laugh very rightfully hard at me. Sentence structure KILLS me! It’s what I’ve been focusing the most on studying lately.

Thankfully, I have the excuse of ‘frisk is 8 not my fault’ I can fall back on!! sdhfkjsad

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

ASL resource

Heyyy, so I’ve kind of been ‘gone’ just because of moving and what not, but like, I was scrolling through reddit and I know some of you follow me for ASL stuff, but I’m kind of finding it tricky to continue asl on tumblr. Call it a christmas miracle but reddit has a sub for asl and I like it. so I figured yall might like it to if you don’t know about it.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

How long has Frisk been learning ASL?

I'll just answer myself- they started in the second semester of kindergarten and spent all of first grade learning it in school. They've been self-teaching (memorizing signs, not grammar) all of second grade.

So, their grammar is supposed to be pretty rudimentary, and they attempt to repeat spoken phrases directly into ASL sometimes, but some mistakes are just straight up on me, lmao

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the reasons i get nervous about drawing answers to asks is because i’m not sure how much ASL i will draw for an answer, and my grammar is still fuzzy

i think i just need to get over this and accept that i will probably mess up and so will frisk because they’re 8 (they are smarter than me though. which makes this hard). i’m going to do my best to keep up with learning, but if anyone wants to correct me, never be afraid

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson ??? American Sign Language

American Sign Language (ASL) is distinct from English. One way to understand the unique features of ASL is to compare it to a language we already know -- English. In the examples below, the underlined English words in ASL sentences require a single sign.

Comparing the two. I can’t get a good screencap so Imma just type it out.

it goes in this order:

English

asl

my comments

Topic-comment structure of sentences

I enjoy listening to country music.

Country music enjoy. ("Country music" is the topic and "enjoy" is the comment).

This is a big house.

This (signed by 1-hand pointing down) house big

I have to buy a car.

Car buy must

Unlike the subject-verb-object word order of English, ASL sentences typically have the topic-comment format. Specify the topic (subject or object of a sentence) and then comment on it.

Need for a verb and a noun

How are you?

how you

I am sorry.

sorry

You are welcome.

welcome

I am really sick ("really" is used to dispel doubt or indicate seriousness of sickness).

True sick I. (True functions like a copula to emphasize the truthfulness of the statement.)

Unlike English, ASL has no requirement that a sentence must contain a verb and a noun. ASL sentences do not use copulas (or state verbs such as are, is, and am) to fill the verb slot in a sentence as English does. Nouns and verbs are often implied.

No articles

WHere is the restroom?

restroom where?

There are no articles (a, an and the) in ASL.

No auxiliary verbs

Do you have any children?

Children have you?

I am writing a letter.

Letter write I

ASL does not use auxiliary (helping) verbs such as do, am, are, etc.

Incorporation (also called agglutination) refers to the enhancement of the meaning either by modifying an existing sign or by adding part of another sign to a sign. In the examples below, help incorporates within itself two pronouns (I and you, she and you, etc.). Number, tense, shape, size, manner of movement, etc. can also be incorporated. Although signing is only half as fast as speaking, the amount of information transmitted per unit time is about the same for both English and ASL. This is possible, in part, because ASL "packs" more meaning into many signs through the process of incorporation.

Many verbs incorporate directionality

I will see you later.

I will help you.

You help me.

You help him.

I help them.

She helps you.

See-you later.

Help. (Sign for help moves from the "helper" towards the recipient[s] of help, taking advantage of the visual-spatial nature of the language.).

Directionality of verbs often substitutes for the subject and object of a sentence in ASL. In the first sentence, the sign for see moves from near the signer’s (subject) eyes towards the conversational partner (object). Thus the sign "see" incorporates the sign "you."

Incorporation of size and manner

He lives in a very big house.

He live house-big.

I need a large plate.

Need plate-large I.

You walk very fast.

Walk-fast you.

The signs for big and plate are made "expansively." Walk is signed with rapid movements of hands to incorporate fast.

#american sign language#american sign language notes#grammar#asl grammar#deaf studies#deaf communications#adventstudies#aslnotes#aslgram

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Signed Pidgin English (SPE)

Yeaaa I got behind on my work lmao.

With adult signers, it is preferable to use American Sign Language (ASL) or SPE. Deaf people generally do not appreciate manual English (Signed English) because (1) it is slow and tedious and (2) it is a distortion of ASL. All of us are attached to our language -- we cherish our mother tongue. Deaf people are no different. They do not appreciate their language distorted by "outsiders" (hearing people) by imposing English grammar on it. However, they realize that all hearing people cannot be expected to learn ASL. Therefore, SPE, which is a blend of English and ASL, has developed as a contact language. In fact, many people refer to use SPE as the "contact language." How to "speak" of SPE? 1. Use English word order. I am a student I student

2. Mark yes/no questions with raised eyebrows and forward leaning and, optionally, with the sign for "question" at the end. Do you want to eat? You want eat?

3. Mark wh-question with a wh-word (what, when, why, who, how, where). When is our final exam? When final exam?

4. Indicate plurality with a quantifier (two, many, a few, etc.,) only; do not use suffix –s. We have two boys We have two boy.

5. Indicate past tense with a time reference (now, later, etc,); do not use suffix –d. Yesterday I went to a party. Yesterday go party. I lived in Ames a long time ago. I live Ames long ago.

6. Avoid prepositions “to” and “of” and use other prepositions such as on, in, and for only if they are necessary to convey meaning. The cost of living is high in this town Live cost high this town. I wrote a letter to my mother Morning write letter mother.

7. Do not use articles “a”, “an”, and “the” My sister is a lawyer Sister lawyer

8. Do not use copulas (linking verbs – is, are, was, were, am, be) Why are you sad Why you sad?

9. Do not use comparative and superlative markers; do use more, less, most, better, best, very, and similar signs. I am taller than you. I more tall than you. That is the tallest building (Point to the building) most tall

10. Do use agent marker when necessary. She is a writer. She writer.

11. Do not use adjectival and adverbial markers Come here quickly. Come quick. I am sleepy. I feel sleep. The sky is cloudy. Sky look cloud.

12. Do not mark third person singular verbs with –s. He works at the factory. He work factory

13. Do not use progressive marker -ing He is eating. He eat. (Context is the only clue; if there is confusion, fingerspell the entire word, in this case, "eating.") 14. Do not use possessive –s or any contractions that are marked with the apostrophe; do use signs for contracted forms can’t, don’t, and won’t. My friend’s marriage is tomorrow. Friend marriage tomorrow. He’s is here but you can’t see him. He here but you can’t see him. (Fingerspell "He.")

15. Do use negation marker as needed. He is not my brother He not my brother (Fingerspell "He.")

16. If the third person or an entity (object, animal, plant, etc.) is present within the eyesight of where the conversation is taking place, simply point to the person or the entity instead of using a pronoun such as he, she, it, etc. However, the person or the entity is not present in the conversation, then fingerspell pronouns (he, she, they, them, it, this, etc., as shown in examples 14 and 15 above).

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson 37: DEAF CULTURE

Thus there are two different kinds of deaf people in this world. The deaf people (lower case "d" deaf) have a medical condition of a severe hearing disability but do not identify themselves as belonging to a separate cultural group. Their culture is the same as that of the hearing people in their homes and the community. The lower case "d" deaf almost always are brought up in the oral tradition and do not normally learn or use a sign language.

The upper case "D" deaf, on the other hand, strongly identify with other like-minded Deaf people and thus belong to a separate cultural group from those of the hearing members of their family and their community. For Deaf people, their deafness is not a disability but simply as a physical characteristic that defines their identity much like someone's skin color or hair type may, in part, help determine one's cultural affiliation. The use of a sign language is the most important characteristic of being Deaf.

We use the lowercase deaf when referring to the audiological condition of not hearing, and the uppercase Deaf when referring to a particular group of deaf people who share a language – American Sign Language (ASL) – and a culture. The members of this group have inherited their sign language, use it as a primary means of communication among themselves, and hold a set of beliefs about themselves and their connection to the larger society. We distinguish them from, for example, those who find themselves losing their hearing because of illness, trauma or age; although these people share the condition of not hearing, they do not have access to the knowledge, beliefs, and practices that make up the culture of Deaf people. (Padden, D. & Humphries, T. (1988). Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture. Cambridge, Ma: Harvard University Press.)

Deaf culture is a way of living built up by Deaf people and passed on from generation to generation. In the hearing community, the cultural values and customs are typically transmitted from parents and other members of the family and the community to a child. However, most deaf children are born to hearing parents who have no exposure to Deaf community and culture. A Deaf child, therefore, derives his/her cultural values and customs, not from the hearing members of the family and the community, but from contact with the Deaf members. Therefore, acculturation -- the process of adopting the cultural values and social patterns of a group different from the one the person is living in -- begins much later for a Deaf child when he/she begins to have regular and extended contact with other Deaf people.

Historically, Deaf culture has often been acquired within schools for the deaf and within Deaf social clubs, both of which unite deaf people into communities with which they can identify. Becoming Deaf culturally can occur at different times for different people, depending on the circumstances of one's life. A small proportion of deaf individuals acquire sign language and Deaf culture in infancy from Deaf parents, others acquire it through attendance at schools, and yet others may not be exposed to sign language and Deaf culture until college or a time after that. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deaf_culture)

A community of deaf people shares certain common values, perceive the world around them in a similar way, and have developed various customs, traditions, and institutions that identify them as a distinct social group. They share a certain world view because of their shared experiences in schools, in their neighborhoods, and in their workplaces. Interestingly, Deaf culture, in the U. S. belongs to those who are culturally Deaf (whether or not audiologically deaf) and who use ASL to communicate. There are some hearing people in the U.S. -- typically living near a school or college for the Deaf -- who interact extensively with Deaf people, are fluent in ASL, and have adopted the world view and the traits of the Deaf people. These people are not deaf (do not have a hearing loss) but are accepted as members of the Deaf community. They are, in other words, culturally Deaf but not audiologically deaf.

Hearing children of deaf parents (children of deaf parents almost always have normal hearing) are often bicultural and bilingual. They learn the sign language, such as the ASL, from their parents and they learn the spoken language of the community through exposure to neighbors, extended family, and through radio and television. Similarly, they learn the values and traditions of the Deaf culture from their parents and the values and customs of the hearing community from the extended family and the community institutions such as the places of worship and schools. A large number of competent interpreters for the Deaf (those who interpret signing to hearing people and spoken words to Deaf people) are the bicultural and bilingual hearing children of Deaf parents.

SOME FEATURES OF DEAF CULTURE

The use of the telecommunication device for the deaf (TDD or TTY) to talk on the phone.

The reliance on closed captioning of TV broadcasts and movies to enjoy these forms of entertainment.

The strong sense of belonging to the school for the Deaf they attended. "Where are you from?," in the Deaf community, usually means "Which deaf school did you go to?" In this sense, their ‘home' is not the home they were born in but their cultural home, which is usually the Deaf school.

Name sign -- all Deaf people give themselves a name sign (or more commonly, another member of the Deaf community gives one a name sign) so that people do not have fingerspell the name every time.

Deaf clubs -- Most large cities with a large enough Deaf community tend to have their own clubs and places of worship where they congregate and interact.

Calling attention -- turning on and off lights (if trying to get the attention of a room full of people) or tapping on arm or shoulder (if seeking the attention of an individual) is the "correct" form of calling attention. Clapping is not acceptable.

The use of assistive listening and other specialized devices (e.g. alarms).

Endogamous marriages (both spouses are Deaf) are very common, estimated at 90 percent among Deaf people. In contrast, the rate of endogamous marriages is much less common in deaf people.

SOME DEAF INSTITUTIONS IN THE U.S.

The following are some selected institutions of the deaf (dates in parentheses are the dates of their establishment). This shows that the Deaf community is vibrant with the range of activities, interests, and accomplishments similar to those of the hearing community.

SPORTS: The International Games for the Deaf (1924), often referred to as the Deaf Olympics; American Athletic Association of the Deaf (1947)

ASL LITERATURE: Oratory (formal speaking); Folklore (puns, games, jokes, storytelling, etc.); Digital literature (CD-ROM, etc.) flourishes even though ASL has no script.

ARTS: National Theatre of the Deaf (1966); Deaf Artists, Inc. (1985); Spectrum: Focus on Deaf Artists (1975); Videos.

ADVOCACY: World Federation of the Deaf (1951); National Association of the Deaf (1880).

RELIGIOUS: Episcopal Conference of the Deaf (1881); National Congress of Jewish Deaf (1956). These two just examples. Nearly all religious faiths and denominations have their own Deaf institutions.

PROFESSIONAL: American Professional Society of the Deaf (1966); National Fraternal Society of the Deaf (1901).

MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT DEAF PEOPLE

The hearing community is generally not well informed about Deaf people. This has resulted in many misconceptions. Some of them are listed below.

Deaf people can't hear anything. Nearly all deaf people have some residual hearing and, with the help of hearing aids and assistive listening devices, they can hear many sounds. However, their ability of understand speech through the sense of hearing alone may be limited.

All deaf people can read lips. The speech reading ability (understanding speech through lip movements, linguistic context, and facial expressions) is, in part, a natural ability. Some deaf people are naturally good speech readers while others, even with training, have only a fair ability.

Deaf people are very quiet. Deaf people make a variety of vocal sounds when engaged in conversation and may even mouth words as they sign.

Deaf people can't talk. Some deaf people talk as well as hearing people although most deaf people have difficulty with pronunciation to varying degrees. The type and the severity of hearing loss and the amount of and the age at which the speech training was obtained only partly determine the speech outcome. Some deaf people with very severe hearing loss are excellent speakers.

All deaf children have deaf parents. In fact, as stated above, over 90 percent of deaf children have hearing parents.

Deaf children can't attend regular school. Nowadays, most deaf children attend their neighborhood schools.

Hearing aids let deaf people hear speech. Modern hearing aids are powerful enough for deaf people to "hear" speech. However, most deaf people encounter great difficulty discriminating the various speech sounds sufficiently to understand what they hear.

All deaf people wish that they could hear. In fact, most Deaf people (but not deaf people) would not want to "give up" their Deafness. They continue to cherish their status as Deaf and view hearing aids or a cochlear implant as a crutch they have to use in order to interact with hearing people.

Deaf people are emotionally disturbed. Deaf people are no more emotionally disturbed than their hearing peers. Most deaf people are emotionally well adjusted.

All deaf people know sign language. In fact, the majority of deaf people in U.S. know very little ASL or none at all. Of course, all Deaf people in this country know ASL as this is the defining characteristic of being Deaf.

Deaf people can’t drive. In the U.S., deafness is not a barrier to getting a driver's license.

Deaf people can’t adopt children. In U.S., all deaf people (whether "deaf" or "Deaf") are allowed to adopt children.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Communication and the Deaf Child

More than 90 percent of all deaf children are born to hearing parents. Hearing parents, of course, do not know a sign language. Moreover, they fear that if their child learns a sign language, he/she will face great difficulty living, learning, and later working in a predominantly hearing world. Therefore, most hearing parents of deaf children prefer to teach them the oral (spoken) language than a sign language. However, the ability of deaf children to learn a spoken language such as English varies greatly. Some deaf children manage to become sufficiently proficient in the oral language to speak nearly as well as their hearing peers. On the other end, many deaf children, even after years of speech and auditory training, fail to acquire sufficient skills to speak intelligibly and use the oral language effectively for communication, education, and work. It is, therefore, desirable for deaf children to be exposed to simultaneous communication -- both speech and sign language. This way, speech and signing can complement each other during communication. The sounds and words they miss hearing can be better understood through signs. There is another reason why children should be exposed to English even if they prefer to communicate only through signing. Whether deaf children learn to speak English well or not, they should necessarily know how to read and write in English in order to do well in education and employment. American Sign Language (ASL) and other sign languages do not have scripts and literacy skills cannot be developed except by exposure to an oral language. Research indicates that deaf children can learn to read and write in English through ASL and manual English (Signed English) equally well. It is, however, important to immerse deaf children in English and signing from infancy for the full development of communication abilities in these children. If signing is to be used with a deaf child in the U.S, American Sign Language (ASL) is the preferred method. However, most hearing parents do not have the time or the inclination to learn an entirely different language. Learning ASL, like learning any other language, requires much time and effort. The hardest part of learning any language is its grammar. Signed English, which we learned in the last 15 lessons, uses English grammar, which the parents already know. Hearing parents of deaf children can quickly learn manual English because they already know the English grammar. They only need to learn the vocabulary, which is, arguably, the easiest part of learning a language. Therefore, for practical reasons, Signed English rather than ASL may be a more achievable solution for hearing parents of deaf children. The acquisition of English literacy involves knowledge of (a) English vocabulary, (b) morphology (structure of words such as plurals, past tense forms of verbs, etc., and (c) syntax (structure of sentences such as subject and predicate). Acquiring adequate English literacy through hearing only is difficult for a deaf or severely hearing impaired child because they do not clearly hear all parts of sentences. Speech (lip) reading is ambiguous and difficult and does not provide sufficient input for literacy development because many sounds are not visible on the lips. Fingerspelling is not useful for young, non-reading children. Children need to know a good deal of language before they can begin to read and fingerspell. Therefore, hearing parents of young deaf children may wish to adopt simultaneous communication (communicating through speech and Signed English). By providing good models (grammatically correct English sentences both in speech and signing), they will lay a strong foundation for the development of literacy when children enter school. However, older children and adults who are deaf generally find manual English too slow, cumbersome, and artificial. By this time they have already acquired the necessary knowledge of English grammar and, therefore, do not need to continue to use Signed English. They may prefer to use Signed Pidgin English (SPE), which dispenses with many of the grammatical features of English that are unnecessary to convey meaning. The SPE sentence structure is, in some ways, similar to that of ASL. Deaf adults, who sign, therefore, prefer to use SPE with hearing people who understand signing. If you want to communicate with deaf adults, you should develop some knowledge of SPE.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson 39: Deaf Identity and the Preservation of Deaf Culture

Throughout history, people with a hearing loss are referred to by many different names. The following excerpt from the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), the organization that represents the largest number of Deaf people in the U. S. states that they prefer to be called "Deaf" regardless of the degree of hearing loss (severe, moderate, or mild). For those who have a hearing loss but are not members of the Deaf community, the NAD prefers the term "deaf" (if they have a severe degree of hearing loss) or "hard-of-hearing" if their hearing loss is in the mild to moderate range.

Deaf and hard of hearing people have the right to choose what they wish to be called, either as a group or on an individual basis. Overwhelmingly, deaf and hard of hearing people prefer to be called “deaf” or “hard of hearing.” Nearly all organizations of the deaf use the term “deaf and hard of hearing,” and the NAD is no exception. The World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) also voted in 1991 to use “deaf and hard of hearing” as an official designation.

Yet there are many people who persist in using terms other than “deaf” and “hard of hearing.” The alternative terms are often seen in print, heard on radio and television, and picked up in casual conversations all over. Let’s take a look at the three most-used alternative terms.

Deaf and Dumb -- A relic from the medieval English era, this is the granddaddy of all negative labels pinned on deaf and hard of hearing people. The Greek philosopher, Aristotle, pronounced us “deaf and dumb,” because he felt that deaf people were incapable of being taught, of learning, and of reasoned thinking. To his way of thinking, if a person could not use his/her voice in the same way as hearing people, then there was no way that this person could develop cognitive abilities. (Source: Deaf Heritage, by Jack Gannon, 1980)

In later years, “dumb” came to mean “silent.” This definition still persists, because that is how people see deaf people. The term is offensive to deaf and hard of hearing people for a number of reasons. One, deaf and hard of hearing people are by no means “silent” at all. They use sign language, lip-reading, vocalizations, and so on to communicate. Communication is not reserved for hearing people alone, and using one’s voice is not the only way to communicate. Two, “dumb” also has a second meaning: stupid. Deaf and hard of hearing people have encountered plenty of people who subscribe to the philosophy that if you cannot use your voice well, you don’t have much else “upstairs,” and have nothing going for you. Obviously, this is incorrect, ill-informed, and false. Deaf and hard of hearing people have repeatedly proven that they have much to contribute to the society at large.

Deaf-Mute – Another offensive term from the 18th-19th century, “mute” also means silent and without voice. This label is technically inaccurate, since deaf and hard of hearing people generally have functioning vocal cords. The challenge lies with the fact that to successfully modulate your voice, you generally need to be able to hear your own voice. Again, because deaf and hard of hearing people use various methods of communication other than or in addition to using their voices, they are not truly mute. True communication occurs when one’s message is understood by others, and they can respond in kind.

Hearing-impaired – This term was at one time preferred, largely because it was viewed as politically correct. To declare oneself or another person as deaf or blind, for example, was considered somewhat bold, rude, or impolite. At that time, it was thought better to use the word “impaired” along with “visually,” “hearing,” “mobility,” and so on. “Hearing-impaired” was a well-meaning term that is not accepted or used by many deaf and hard of hearing people.

For many people, the words “deaf” and “hard of hearing” are not negative. Instead, the term “hearing-impaired” is viewed as negative. The term focuses on what people can’t do. It establishes the standard as “hearing” and anything different as “impaired,” or substandard, hindered, or damaged. It implies that something is not as it should be and ought to be fixed if possible. To be fair, this is probably not what people intended to convey by the term “hearing impaired.”

Every individual is unique, but there is one thing we all have in common: we all want to be treated with respect. To the best of our own unique abilities, we have families, friends, communities, and lives that are just as fulfilling as anyone else. We may be different, but we are not less.

Some Controversial Aspects of Deaf Culture

Opposition to Cochlear Implant

Deaf (the upper case "D" Deaf) people are worried that the cochlear implant will eventually result in the abolition of deafness and, with it, the Deaf culture and deaf languages such as ASL. The National Association of the Deaf (NAD), the advocacy group for Deaf people in the U.S.initially opposed the use of cochlear implant. They argued that deafness was not a disability but simply a difference, Deaf like being deaf and are proud of their Deafness. "Deaf pride" is a frequently used term in the Deaf community.

Later the NAD conceded that adult deaf have the right to have cochlear implants if they so chose but opposed the use of cochlear implants for children. They argued that the hearing parents of deaf children (most deaf children are born to hearing parents) should not decide whether their child grows up to be an oral deaf (one who uses a spoken language and considers herself/himself to be part of the hearing society) or Deaf (one uses a sign language and regards himself/herself to be part of the Deaf community). The decision should be left to the child when she/he is old enough to make a decision. However, the development of a language (whether signed or spoken) is age-critical; if children do not learn the language in the first few years of their lives, they will never catch up later. Therefore, waiting until the child is 16, 18, or 21 years old to decide whether to have a cochlear implant is not practical.

Still later, under heavy criticism of its position that hearing parents should not make decisions that affect the future and wellbeing of their children, NAD has conceded that hearing parents indeed have the right and the responsibility to bring up children in ways that they consider is in the best interest of the children. Nonetheless, NAD is generally opposed to the widespread use of cochlear implant technology.

Deaf people who have a cochlear implant are not well accepted by the Deaf community. At Gallaudet University (a liberal arts university for the deaf located in Washington D. C.) and other predominantly sign language based deaf schools, students who have cochlear implants are pressured not to use them by other students.

Wanting Deaf Children

Some members of the Deaf community actively seek to have deaf children. They seek the services of geneticists and use a modern reproductive technology -- preimplantation genetic diagnosis, or P.G.D., a process in which embryos are created in a test tube and their genetic makeup is analyzed before being transferred to a woman’s uterus -- to maximize the probability that they have a deaf child. In 2002, The Washington Post Magazine reported on a deaf couple from Maryland who both attended Gallaudet University and set out to have a deaf child by intentionally soliciting a deaf sperm donor. For them, “A hearing baby would be a blessing; A deaf baby would be a special blessing.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

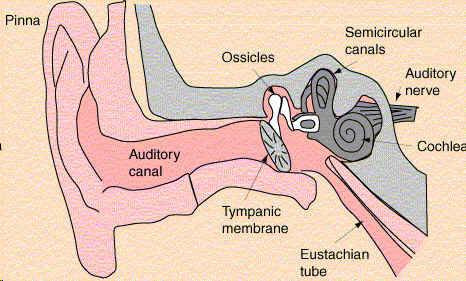

Lesson 18: Parts of the Ear

I hate that this comes after the text I just had which, oddly enough was about the parts of the damn ear.

To understand deafness, we should know a little bit about how we hear. Then we can talk about what can go wrong with it.

The ears are located, for the most part, within the temporal bones on either side of the skull. Anatomically, the hearing mechanism may be divided, going from the outer to the innermost structures, into

1) the outer ear or external ear,

2) the middle ear,

3) the inner ear

4) the neural auditory pathway.

Functionally, the auditory mechanism may be divided into

1) the sound-conducting portion (the outer and the middle ears),

2) the auditory-neural encoding portion (the inner ear and the auditory nerve) and the auditory information-processing portion (the neural auditory centers in the brain).

Outer Ear:

The outer ear, the visible portion of the ear, consists of the auricle (pinna) and the external auditory canal (EAC). The pinna, whose shape and size show considerable individual variations, is intended to serve as a funnel to gather sound from the environment. It, however, appears to be a poor gatherer of sound in humans.

The pinna's complicated reflective surface consisting of many grooves and pits appears to provide some information to the brain for localizing the source of sound, particularly those sounds that occur at a midline point above, below, in front of, or at the back of the head.

EAC is a tube for conducting sound from the pinna to the eardrum. The EAC resonates (amplifies) sounds in the frequency range of approximately 2000 - 4000 Hz, making our ears more sensitive to sounds in this frequency range.

Middle Ear:

The tympanic cavity (middle ear cavity) and the structures contained within it make up the middle ear. The tympanic cavity is a small, irregularly shaped, six-sided, air-filled cavity located in the temporal bone of the skull. The tympanic membrane (eardrum), which separates the outer ear from the middle ear, is a cone-shaped, thin, elastic membrane.

A chain of three small bones, the malleus, the incus, and the stapes, suspended delicately within the middle ear cavity, connect the eardrum to the inner ear structures. The three bones are collectively called the ossicles.

Middle Ear Functions:

The primary function of the outer and the middle ears is to conduct sound to the inner ear. The sound is collected at the pinna and channeled to the eardrum by way of the external auditory canal. The eardrum oscillates into and out of the middle ear cavity in response to the alternating high-low air pressure created by the incoming sound. The vibration from the eardrum is transferred to the ossicular chain, which vibrates in phase with the movement of the eardrum. The ossicular chain conducts the sound to the inner ear.

In addition to this air conduction, which is the primary mode of sound transmission in the ear, sound is also transmitted to the inner ear through bone conduction - by way of vibration of the bones of the skull - if the decibel levels of the sound are sufficiently high to set the molecules of temporal bones into vibration. Recall that sounds do travel through solid objects like walls and bones of the skull when they are strong enough.

Have you ever tried to listen to people sitting by the side of the pool talk while you are under water? Unless the people were shouting, chances were that you could hear only muffled sounds. This is because most of the energy in the air-borne sound, when it reaches the surface of the water, is reflected back. Only a small portion of the sound energy penetrates the water to reach your ears under the water. A similar situation exists in the ear.

The air-conducted sound in the outer ear reaches the liquid-filled cochlea of the inner ear through the middle ear. This results in a loss of acoustical energy equal to about 30 dB. The middle ear compensates for this loss of acoustical energy by amplifying the sound coming into the middle ear. The middle ear also provides some degree of protection from damagingly loud sounds. When very loud sounds reach the middle ear, two muscles in the middle ear cavity contract, partially immobilizing the ossicular chain. The contraction of the middle ear muscles, the acoustic reflex, is triggered when the sound reaching the middle ear is in excess of 80 dB. The reflex increases the stiffness of the ossicular chain and thus reduces the sound pressure level reaching the inner ear. The protection of inner ear from loud, damaging sound provided by the acoustic reflex is small; moreover, the reflex has a latency (delay) of 60 to 120 milliseconds and, therefore, cannot protect ear from sudden, loud sounds.

The Eustachian Tube:

Swallow your saliva real hard and you should feel air pressure in the middle ear cavity rise. The Eustachian tube extends from the upper part of the throat near the base of the skull to the middle ear cavity. The tube equalizes the air pressure between the external ear canal (where the pressure level is the same as the atmospheric pressure) and the middle ear cavity. If the pressure on two sides of the eardrum is unequal, then the eardrum tends to be pushed in the direction of the lower pressure, making it less responsive to sound. The Eustachian tube prevents this from happening.

Sudden changes in outside pressure, as might happen when an airplane takes off or lands, stretch the eardrum to the point of being painful. Yawning, swallowing and sneezing would cause the Eustachian tube to open up, equalizing the pressure between the outer ear and the middle ear. In young children, the Eustachian tube is about half as long as in adults and is straighter, providing an easy route for the spread of upper respiratory infections from the throat to the middle ear. This is, in part, the reason why babies tend to have frequent middle ear infections.

#american sign language#adventstudies#long post#studyblr#langblr#sign language#notes#grammar#structure#ear#aslnotes#aslgram

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson 36: Education of Deaf Children

Oralism - Manualism Controversy

At the time Abbe de l'Epee was using French Sign Language (FSL) to educate deaf in France, educators in England were exclusively using "oral methods" (only speech; no signing or fingerspelling) to teach deaf children. Ever since, there has been a controversy about the "best" method for educating the deaf. Should deaf children be educated through their "natural language" based on signing or should they be taught through spoken language only?

Some deaf children, with hearing aids and intensive speech and auditory training, can develop highly intelligible speech and function well in a school that uses only speech. However, many deaf children would find it difficult to learn exclusively through speech because even powerful hearing aids do not allow them to discriminate speech well enough to understand all or most of what is said to them.

Moreover, they do not hear their own speech well enough to correct errors in pronunciation. Many deaf children educated through oral methods fail to develop intelligible speech. As these children grow up, they may find themselves without a viable means of communication. They cannot communicate through sign language because they have not learned it. They cannot communicate effectively through speech because they do not know it well enough to understand others speech or develop clear speech themselves.

On the other hand, exclusive reliance on signing and the failure to develop any speech at all puts the child at risk for being isolated from the dominant hearing society. They can only communicate with other deaf signers and with hearing people with the help of interpreters. This may cause difficulty in realizing their full potential in social relationships, education, and employment. Moreover, regardless of whether a deaf child learns to speak or not, he/she must learn to read and write in a spoken language.

ASL and other sign languages around the world do not have a script and, therefore, written materials like books are not available in these languages. There have been numerous attempts to develop a script for ASL, but there is not yet a useful, widely accepted script for it. Teaching how to read and write in a script based on a spoken language such as English using a sign language such as ASL has proven to be very difficult. Many deaf children educated using the manual methods (sign language and fingerspelling) fail to develop adequate knowledge of reading and writing to succeed in education.

In US, Thomas Gallaudet championed the use of signing to educate deaf. Alexander G. Bell, a contemporary of Gallaudet (and the inventor of the telephone), advocated oralism. The Gallaudet University in Washington, DC and the National Association of the Deaf (an advocacy organization of Deaf people in the U.S.) are in favor of the use of ASL with and among deaf. They do not oppose the use of speech but strongly argue for the use of ASL with all deaf people in this country.

They do not approve of Manual English and only support the use of SPE when interacting with hearing people who do not know ASL. They regard manual English as a corruption of their language (ASL) and, therefore, offensive. On the other hand, the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf, a large and influential organization of teachers and parents of deaf children in the U. S. and Canada, among other organizations, favors the exclusive use of speech with and among deaf. Thus the oralism-manualism controversy that started in the 18th century continues to this day!

Deaf Education Institutions

Until the early part of the 19th century, there had been no systematic attempts to educate the deaf. In the U.S.wealthy Americans sent their deaf children to England for education. The American School for the Deaf (1817), formerly the American Asylum for the Deaf, in Hartford, CT is an example of a school in the US using manual approaches to the education of the deaf. The Clark School for the Deaf (1867), Northampton, MA is an example of a school that uses oral methods to educate the deaf. Today nearly all states have one or more state-sponsored special residential schools for the deaf that use an eclectic approach (a combination of oral and manual approaches) to educate deaf children.

The Gallaudet University founded in 1849 by Edward Gallaudet is the only liberal arts college for deaf in the world. National Technical Institute for the Deaf (a part of the Rochester Institute of Technology) in Rochester, NY is an engineering school for the deaf. Most colleges in the U. S. now have support services for deaf including note-taking, tutoring, assistive listening devices, interpreting, and counseling.

Methods of Educating the Deaf

AURAL METHOD: Use of the residual sense of hearing in the deaf with the help of hearing aids, assistive listening devices, and/or cochlear implants. This is a natural way of learning to speak and, if successful, it results in natural-sounding speech.

AURAL-ORAL METHOD: The residual sense of hearing as described above and speech reading (lip reading) are used for communication and education. Cued speech, a gestural system to help deaf read speech better, may be used to develop speech reading. The addition of speech reading distinguishes this method from the previous method.

THE ROCHESTER METHOD: All of the techniques of the aural-oral method along with fingerspelling are used to educate the deaf. The addition of the fingerspelling distinguishes this method from the previous method.

SIMULTANEOUS (TOTAL COMMUNICATION) METHOD: In addition to all of the techniques above, signing is also emphasized. As the name suggests, the total communication method employs all available means of communication - e.g. pictures, pantomime, reading, writing, signing, speaking, etc. The addition of signing distinguishes this method from the previous method.

The first three methods are oral methods because they emphasize the development of speech and rely on hearing for the most part. The last method -- simultaneous or total communication method -- is a manual approach. Although it does include the development of speech, it is heavily dependent on the use of signing.

About 50 years ago, most deaf children were educated in special residential schools for the deaf. Today, however, most deaf children live at home and receive education in neighborhood schools.

MAINSTREAMING is the term used to refer to the process of educating children with special needs such as hearing-impaired children along typically developing children in regular schools instead of being segregated in special schools. SELF-CONTAINED CLASSROOMS are specially-equipped and staffed classrooms in a regular school for the education of children with special needs.

A self-contained classroom for hearing-impaired children will have assistive listening devices discussed earlier and will be staffed by teachers certified to teach hearing-impaired children.

Mainstreamed children spend a part of the school day in these classrooms and the rest of the time in regular classrooms. ITINERANT PROGRAMS are for children who are mainstreamed into regular classrooms.

An "itinerant" teacher of the hearing-impaired (a teacher who goes to different schools on different days) provides specialized educational services to a child in a neighborhood school. The amount of time and number of days that a child receives such support varies according to the student's needs. Because hearing impairment is a low incidence disorder and a neighborhood school may have only a few (often just one) hearing-impaired children, this model is cost effective.

#asl#american sign language#american sign language grammar#deaf communications#deaf studies#adventstuides#studyblr#langblr#aslgram#aslnotes

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey I can't seem to find all your asl lessons in one spot. I'm having a lot of trouble to find lesson one. I might be blind and not seeing it but if you can please direct me or send me the link to them all <3

mhm. I see your problem lmao. Uhm, let me see if I can gather everything. here’s one set yeeaaa it doesn’t help that somewhere along the line I actually stopped labeling them lmao. here’s the page that has lesson one. I think that might be all the lessons I have. and I think the first two listed here aren’t ones you can find in the other links. that should be all of them currently c=

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Assistive Devices and Services for the Deaf

Many television programs in the United States and many other countries are “closed captioned” in that the audio portion of the program is displayed in text form on the screen. The “captions” are closed in the sense that the text of the audio portion of the program is normally hidden from the viewers. Hearing-impaired viewers may choose to follow the program by turning on the decoding of the hidden signal. In the United States, the Television Decoder Circuitry Act of 1990 mandates that all televisions manufactured for sale in the U.S. after July 1993 must contain a built-in caption decoder if the picture tube is 13" or larger. Older television sets will need a special external decoder to display captions. An increasingly larger portion of television broadcast in the United States now includes closed captioning. The U. S. Federal Communications Commission has a mandate requiring that 95% of all television broadcasts should have closed captioning.Alerting and Signaling DevicesPeople who have severe hearing impairment cannot rely on standard alarm clocks, doorbells, telephone ringers, or smoke detectors. In addition, hearing-impaired parents may not be able to hear the cry of their young children. In all these situations they will require special devices that provide visual and/or tactile alerts in the form of flashing lights, body-worn vibrators, or vibrating pads that may be placed under a pillow. Both portable and stationary alerting devices are available. Portable devices such as an alarm clock with a vibrating pad can be carried with the user when traveling or even from room to room within the house. Stationary systems equip the entire house or any part of it for a single (e.g., baby-cry detector) application or for multiple devices (telephone, doorbell, smoke/fire alarm, etc.).Hearing-impaired people whose speech may not be intelligible in telephone communication rely on text telephones. Text telephones, which are also known as TTY machines (teletype machines) or TDDs (telecommunication devices for the deaf), require communication partners at either end of a telephone connection to type out their messages instead of speaking them. The technology is similar to chat rooms found on the Internet where people communicate in real time by typing their messages. However, unlike computers, which use ASCII codes to transmit text, text telephones use a coding system called Baudot. A text telephone cannot communicate with a computer without special software to convert Baudot code into ASCII code. Some modern text telephones have the option of using either the Baudot code (which is certainly required to communicate with an older text telephone) or ASCII. The text telephone consists of a keyboard and a LCD (liquid crystal display) screen that holds a line of text. It signals an incoming call by flashing lights or, optionally, by way of a vibrating wristband. There are an estimated 4 million users of text telephones, which is useful not only to deaf people but also others with severe speech disorders.

Several companies such as DT Interpreting provide on-demand remote ASL interpreting via two-way video links over the Internet. For instance, a deaf patient who uses ASL for communication in a local hospital can communicate with the hearing medical staff through an interpreter located in another city. The remotely located interpreter watches the deaf patient's signs on a monitor. Similar the deaf patient watches the interpreter on a monitor. The medical staff speaks to the interpreter, which is relayed to the patient by the interpreter through ASL. The patient's signed messages are relayed to the medical staff by way speech by the interpreter. While an on-site interpreter is the best solution in these situations the cost and the availability of a "live" interpreter has led to the development of these high-tech innovations.

Every state in the United States has a message relay center (MRC) to connect people who use text telephone with people who use a standard telephone. MRC is useful when a person, who does not have a text telephone, needs to initiate calls to or receive calls from a text telephone. The operator in the MRC uses a text telephone and a voice telephone to relay messages between the two parties. MRCs make it possible for text telephone users to connect to any telephone, not just other text telephones. The calls handled by MRCs, although operator assisted, are charged at the same rate as regular telephone calls. In the U.S., text telephones can be used to summon emergency assistance by directly dialing 911 (in areas where this facility is available) without going through an MRC.

In the United States, major hotels and motels fall under the Americans with Disabilities Act which requires them to provide a hearing-impaired guest with assistive equipment. When a reservation for a hearing impaired person is made, a request for a TTY or amplified phone, closed caption decoder (if necessary), door knocker, and a visual signal smoke alarm may be made.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Types of Assistive Listening Devices

Assistive listening devices (ALDs) are special purpose listening devices that pick up sound from the source (e.g., speaker) and deliver it to the ear or the hearing aid of the person, reducing noise interference. ALDs are based on electromagnetic transmission (for group listening such as in classrooms), infrared light transmission (listening to music, TV, etc.), or frequency-modulated (FM) radio waves (meeting rooms, theaters, etc.)

Induction Loop (Teleloop)

This technology is based on electromagnetic transmission. A teleloop system consists of an amplifier and a wire (the loop) installed along the perimeter of the room. When the teleloop amplifier is connected to an audio source such as a TV, radio, or a public address system, the sound is transmitted directly to the receiver or hearing aid worn by the listener. Many hearing aids are equipped with a telecoil (T-coil) that can receive electromagnetic transmission from telephones and induction loop systems. When using T-coil equipped hearing aids, no additional receivers are required to receive teleloop transmission. Room size and architectural considerations may, however, make it impossible to install teleloop systems in some facilities. The teleloop system is also not portable making it less desirable for individual use outside the home. The electromagnetic signals from the loop can pass through walls, ceilings, and floors. Because of this “spill over” effect, separate induction loop systems normally cannot be used in adjacent rooms. Induction loop systems are commonly used in classrooms for students with hearing impairment. In such classrooms, the words spoken by the teacher wearing a microphone are directly transmitted to the hearing aid of the student bypassing the noise of a regular classroom.

FM System

Personal FM systems are similar to FM radio broadcast systems. However, unlike FM radio broadcasts, which operate in the 88 to 108 MHz range of frequencies, the FM systems for private broadcasts utilize frequency bands in the range from 72 to 76 MHz and from 216 to 217 MHz. The 72 to 76 MHz band is available for all private broadcast applications including ALDs. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the U.S. has reserved 216 to 217 MHz band for ALD applications only. Since each system may use its own broadcast frequency, several systems can operate simultaneously at one location without interfering with one another. The personal FM listening devices consist of a transmitter microphone used by the speaker and a receiver worn by the listener.

Unlike the loop system, the FM system requires a special receiver for each listener, whether s/he has a hearing aid or not. There are several types of FM receivers. The under-the-chin type stetoclip or Walkman type headset is available for those who prefer not to use a hearing aid in conjunction with the FM broadcast ALD. A neck loop (personal teleloop) receiver is available for users of T-coil equipped hearing aids. FM broadcast ALDs are highly portable and have a broadcast range of up to 300 meters (nearly 1,000 feet). They are appropriate for communication in situations where the speakers and/or the listeners are on the move (e.g., taking a walk), in small group discourses, as well as in hospitals and nursing homes. It is also possible to incorporate private broadcast FM systems into public address systems in theaters, convention halls, places of worship, and other places that routinely use amplified sound. In such situations, speakers need not wear a separate broadcast microphone.

FM broadcast ALDs cannot be used for confidential communication because anyone tuning into that frequency within the broadcast range can listen to it. Certain FM broadcast ALDs also have the potential to amplify sounds in excess of 140 dB, endangering the residual hearing of users of such systems.

Infrared System

The infrared light ALDs make use of the same technology found in household remote control devices. Infrared light is a part of the light spectrum not visible to the human eye. In infrared ALDs, a modulated infrared carrier beam delivers speech and other sounds from the source to a receiver worn by the listener. A major consideration in the use of infrared ALDs is the need to maintain a direct line of sight contact between the transmitter and the receiver. There cannot be any physical obstruction between these two elements. Unlike FM systems, which are susceptible to radio interference, infrared systems provide a high quality signal. However, the presence of high levels of incandescent light ("tube light") may reduce signal quality. The range of infrared systems is typically limited to under 50 meters (about 150 feet).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson 17: THE SOUND

Learning any language also involves learning about the people who use that language. If you are learning Spanish, you should have some understanding of the geography, history, and culture of the Spanish people. When learning signing and American Sign Language (ASL), we should learn about hearing impairment and the history and culture of Deaf people. In order to understand deafness, we should know a little bit about the nature of sound.

You have heard the age-old question: If a tree falls and there is no one there to hear it, does it make a sound? The answer depends on whether you consider sound as a physical event or a sensory experience. Sound is a physical event and, as such, it is governed by the laws of physics (specifically, a branch of physics called mechanics). The study of the physical properties of sound is called acoustics. Sound is also a psychological experience and, therefore, it is important to know how a living organism receives and processes sound. There are lawful relationships between the physical properties of sound and its perception. The branch of acoustics that relates the physical properties of sound to its perception is called psychoacoustics.

Sound is not a thing. It has no substance. From a physical point of view, sound is a form of energy that propagates as a pressure wave. Sound is the result of rapid and repeated up and down variations in pressure within a medium. The sounds we hear exist in the medium of air although, as anyone who has eavesdropped on his/her neighbors can attest, sound also travels through solid objects like walls. Sound waves in the air are simply rapid and repeated rise and fall in the air pressure from a relatively static (stable) reference pressure (Figure 1). The reference air pressure is typically the atmospheric pressure. Sound travels in its medium in the form of alternate compression (momentary increase in pressure) and rarefaction (momentary decrease in pressure). The sound waves traveling in air alternately fall slightly above (compression) and below (rarefaction) the atmospheric pressure.

Each instance of up-down variation (or down-up variation) in the pressure of a sound wave constitutes a cycle of sound. How many cycles do the sound waves A, B, and C have? The number of complete cycles occurring in one second is the frequency of sound. Frequency is measured in Hertz - abbreviated Hz, which stands for cycles per second. The frequency range of human hearing is approximately 20 - 20,000 Hz. A young adult with no history of hearing or ear problems is typically able to hear sounds that oscillate just 20 times per second (e.g., slow rustle of leaves in the wind) to 20,000 oscillations per second (e. g., the high-pitched sound of some bird calls). Of course, ear infections, exposure to high levels of noise, and other factors that may damage hearing would reduce the audible range of frequencies. The audible frequency range, especially at the higher end of the scale, also diminishes with advancing age. What is the frequency range of hearing in dogs? A Google search might give you the answer!

The frequency of sound is a physical phenomenon that can be objectively measured with appropriate instruments. Subjectively, we perceive frequency as pitch. Although sounds that have higher frequency are perceived as having a higher pitch and vice versa, the relationship between pitch and frequency is not linear. Human beings are most sensitive to frequencies between 1,000 Hz and 4,000 Hz and we can make fine distinctions in pitch in this frequency range. At frequencies below 1000 Hz and above 4000 Hz, our ability to relate pitch to frequency becomes less accurate.

Sinewaves are the simplest types of sounds possible. Each cycle of sound in a sinewave has a single, simple up-down pattern, however, most sounds in nature, including speech and music, are complex sounds made up of many sinewaves of different frequencies.

Complex periodic sounds repeat themselves at regular intervals of time. Complex aperiodic sounds, which we normally perceive as noise, have a random rather than a repetitive pattern. The predictable, repetitive patterns of complex periodic sounds give them a musical quality and a definite pitch. Most musical instruments and the human voice produced at the larynx (voice box) are examples of complex periodic sounds. A note produced on the piano is a complex periodic sound. Most machine noises and the consonant sounds such as the /s/ and /f/, which are not produced at the larynx, are complex aperiodic sounds. Although we perceive /s/ to be of higher pitch than the /f/ sound, we can place neither sound on a pitch scale because they lack a definite pitch. Unlike the noisy consonants such as /s/, the vowels and the noiseless consonants, such as /m/ and/l/, have the repetitive patterns of complex periodic sounds and, therefore, an identifiable pitch. The point of this discussion is that all speech sounds are complex and some are periodic and others are aperiodic. The vowels are relatively low frequency and high intensity (louder) sounds and people with hearing impairment have less trouble hearing them. Vowels are complex periodic sounds. In contrast, the relatively high frequency and low intensity consonant sounds (which are complex aperiodic) such as /p/, /k/, /f/, and /s/ are difficult to hear for people with hearing impairment.

The magnitude of pressure variation in a sound wave - by how much the rise and fall in the pressure deviates from the reference pressure - is the pressure level of the sound. The sound pressure level (SPL) is measured in decibels, abbreviated dB. The smallest pressure variation that gives rise to the sensation of sound in young adults with superior hearing ability is equal to 0 dB. Zero dB, therefore, does not mean that there is no sound; it refers to an arbitrary sound pressure level roughly equal to the softest sound some of us with superior hearing ability can hear. The most intense sound we can tolerate without feeling a tickling sensation or pain in our ears is equal to 120 dB. The dynamic range - the audible range of sound pressure variations - is, therefore, equal to 120 dB (0 - 120 dB).

In physics, the unit of measurement of pressure is pascal. The smallest audible sound pressure level - 0 dB - is equal to 20 micropascals (20 parts out of one million parts of a pascal). This is an extremely small amount of pressure compared to, for example, the atmospheric pressure (101,325 pascals) at sea level. Atmospheric pressure is the air pressure that is bearing down on the surface of our bodies. Even the pressure level that produces an uncomfortably loud sound - 120 dB - has only 20 pascals of pressure. Our ears are highly sensitive to very small pressure variations.

Loudness is how we perceive sound pressure variations. Our ears are responsive to an enormous range of pressure variations. The loudest sound we can tolerate (120 dB) has one million times more pressure than the softest sound (0 dB) we can hear! However, there is no direct, one-to-one correlation between decibel values (sound pressure levels) and loudness. A given SPL value in the range of 1,000 to 4,000 Hz (the frequencies to which our ears are most receptive) will sound louder than the same dB value at other frequencies.

Note that if you stand underneath a jet aircraft with its engines running, the sound will be so intense that you will feel pain in your ears. People working in such environments will need to wear ear protection devices. Similarly, if you are close to the stage in a rock and roll concert, you will probably find the sound level uncomfortably loud.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson 40: Cochlear Implant and the American Sign Language (ASL)

Many members of the Deaf community are concerned that the widespread use of cochlear implants especially by young children will cause the destruction of Deaf culture and ASL. It must be pointed out however, that a cochlear implant is not a cure. If the person does not wear the external parts of the cochlear implant or turns off the speech processor, the person will be unable to hear. Electronic components are easily damaged by exposure to moisture. Therefore, while swimming, in the rain, or participating in water sports, it may not be possible to use a cochlear implant.

Electronic components also sometimes fail to work. While these components are repaired or replaced, the person will be unable to hear. Therefore, it is important to have a backup communication system for users of cochlear implants. A sign language can be such a system especially if hearing members of the family learn to communicate through signing. The following excerpt about the use of signing along with a cochlear implant is taken from: Nussbaum, D. (2003) Cochlear Implants Navigating a Forest of Information…One Tree at a Time. .

The Debate

Professional opinions in both medical and educational environments vary as to the reasons why sign language should or should not be used with children who have a cochlear implant. Professionals who advise against the use of manual communication for children with a cochlear implant believe that promoting total reliance on, and immersion in, the use of the auditory channel maximizes the potential the implant provides to develop useable hearing and spoken language. These professionals warn that the use of sign language significantly reduces the amount and consistency of post-implantation spoken language stimulation for the child, promoting dependency on visual communication, and causing further delay in spoken language development

Other professionals maintain that sign language and spoken language can be developed and used to complement and supplement each other. They believe that effective educational environments can be designed to facilitate and maximize a child’s language and communication skills in both sign language and spoken language, and that these approaches can work harmoniously to support a child’s overall language, cognitive, social, and academic development.

Growing Support for the Use of Sign Language

When cochlear implants first became available, the majority of families choosing this surgery appeared to be those families who were already strongly committed to oral education. As use of the technology has become more widespread, it appears that children who are obtaining implants have a broader range of education, communication, and family environments with a wider range of goals. An “auditory only” approach to communicating with implanted children is often strongly recommended by hospital implant centers and is an effective choice for many. However, communication approaches involving the development and use of both spoken and signed language for implanted children are gaining support. The choice to implant a child is no longer solely associated with the desire to seek an “oral only” education for him or her. Of 439 families of school-aged children with cochlear implants questioned in a 1997-1998 survey by the Gallaudet University Research Institute, two-thirds of the families continued to use sign language as a support for communication in the home. Amy McConkey Robbins, in volume 4, issue 2, of Loud and Clear, a publication of the Advanced Bionics Corporation, states that “a substantial proportion of children with cochlear implants utilize sign language” and that “pediatric implantees” are about equally divided between those who use oral communication and those who use total communication. While use of solely oral communication strategies may meet the needs of one segment of the population of implanted children, it appears that sign language can have a role in the language, communication, education, and identity of children who use cochlear implants.

What Literature Reports About Sign Language and Cochlear Implants

Limited research has been done in the area of cochlear implants and the use of sign language. As the earliest group of implanted students were mostly involved in oral environments, there has not been sufficient time to evaluate longitudinal outcomes for implanted students who use sign language. Some of the literature available on the topic of sign language use for implanted children includes the following statements supporting its benefit:

“Continued use of a total communication (TC) approach might be the most effective means for facilitating language growth in a child with a cochlear implant. Nonetheless, it is essential that the child be exposed to an enriched auditory environment for as many hours a day as possible. There is a great need for a strong commitment to maximize the auditory component with a TC approach. In addition, it might be necessary for the school staff to adjust their expectations and teaching priorities, especially if manual communication is the focus of the child’s educational placement.” (McKinley, A., & Warren, S. (2000). The effectiveness of cochlear implants for children with prelingual deafness. Journal of Early Intervention, 23.) (Instructor Note: TC includes signing; authors are suggesting that system of communication that includes signing may be the most appropriate for young children with cochlear implants),.

“It seems that a child who is a good communicator before implantation, whether silently or vocally, is likely to have good speech discrimination ability in later years.” (Tait, M., Lutman, M. E., & Robinson, K. (2000). Preimplant measures of preverbal communicative behavior as predictors of cochlear implant outcomes in children. Ear and Hearing, 21, pp 18-24.) (Instructor Note: Having any language, whether signed or spoken, is an advantage for the development of speech in children with cochlear implant).

“One observation seems equally sure: Being exposed to two languages from birth, by itself, does not cause delay and confusion to the normal processes of human language acquisition.” (Petitto, L. A., Katerlos, M., Levy, B., Gauna, K., Tétrault, K., & Ferraro, V. (2001, June). Bilingual signed and spoken language acquisition from birth: implications for the mechanisms underlying bilingual language acquisition. Journal of Child Language,28, pp 453-496.) (Instructor Note: The simultaneous development of both signed and spoken language will not cause a delay in the development of either language; on the contrary, they may support each other).

“…it is important that guidelines be developed to identify children who are not benefiting from cochlear implants while they are still young enough to acquire language through other means…the overall cognitive and psychosocial development of children will be negatively affected if they do not have access to a shared language system with which to communicate with family members, other children, and other adults during their early years.” (Spencer, P. (2002). Language development of children with cochlear implants. In I. Leigh & J. Christiansen, Cochlear implants in children: Ethics and choices. Washington, DC: Gallaudet Press.). (Instructor Note: A small number of children with cochlear implant fail to acquire sufficient competence in spoken language. These children need to be identified early on and provided with systematic exposure to signing.)

How Sign Language Serves as a Foundation for the Development of Spoken Language? (The following is from: Koch, M. (2002). “Sign Language as a Bridge to Spoken Language,” handout disseminated at the conference, Cochlear Implants and Sign Language: Putting It All Together, held April 11-12, 2002, at Gallaudet University.)

As a supplement to early language development: Sign language can provide babies and toddlers with a system to symbolically encode the experiences of their lives—through a sensory system that is intact—that is, vision. The auditory system of a profoundly deaf child (pre-implant) will provide very limited access to the auditory based communication system of spoken language.

As a clarifier in development of listening: As a child’s auditory skills begin to develop through a cochlear implant, the world of sound can be overwhelming, especially the rapid, complex barrage of spoken language. As a child learns to associate sound with meaning, signs can be used to bridge the new experience of sound with the familiar experience of visual language.

As a cataloging system for new experience: A young child is constantly experiencing new things—people, places, things, concepts, emotions, etc. The fledgling auditory system is not capable of “capturing” and “filing” these new experiences through audition alone. New experiences can be encoded quickly through the mature system of vision, and can later be transferred—quickly and easily—to the auditory system.

1 note

·

View note