#and they told my grandparents (whose parents were born in italy) and they were very excited

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

MY MORTAL PARENTS, FAMILY & ANCESTRY:

MY ROMAN & ITALIAN ANCESTRY:

I was born at around 1 pm, on Saturday, the 20th of June, 1998, in the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia-The same day that the ancient Romans annually celebrated the festival of the Roman nocturnal storm, god, Summanus, as well as the Rosalia (rose) festival where the Romans payed tribute to the dead and the year that the Roman revivalist organisation, Nova Roma was founded (it's no wonder that I am so Roman, favour roses and have storm powers).

My mortal parents, Teresa Varrese and Roberto Dal Col are Calabrian Italians.

All my grandparents migrated from Italy to Australia, so I am fully-Italian. My mortal dad told me about how his mum was so strong that would break a broomstick in half with her teeth or bare hands, when she got angry. She was like a posh princess with a female Spartan warrior side.

Four of my grandparents are from Calabria, in Southern italy, which was Greece (Magna Grecia) and probably inhabited by Spartans, in ancient times. Perhaps, I have lots of Spartan ancestors from Calabria. That would explain where I get my Spartan warrior ideas from and how my Calabrian grandma could bite a broomstick in half with her bare teeth.

My maternal great-grandfather might have been a police officer, in italy or served in the army. My great-uncle was definitely a police officer in italy, though. Maybe he got it from his father

My paternal great-grandma, Maria's surname, Romeo (Latin: 'to Rome') originates from medieval Rome and The Eastern Roman Empire.

The ghosts of my Roman ancestors (Lares), including Roman soldiers and those from the Romeo family have been there for me, throughout my life. They guide, comfort, protect, enlighten and accompany me. We feast, drink, sleep, shower, laugh, hang-out, go to outings and have fun together. They taught me what it means to be a true Roman and raised me to be like one.

One of my ancestral guardian spirits who often accompanies me is a noble Roman from the renaissance whose full name is Marco Romeo. He looks like a statue of a Roman god with short black hair, blue eyes and fair skin. Marco lived in a villa, in the countryside of Rome. He was an expert at jousting and sword-fighting.

I also had many past-lives as my Roman ancestors, including a past-life as Marco Romeo and a hundred Roman soldiers. Many demigod children of Mars have lots of past-lives as Roman soldiers and warriors. Our divine-father, Mars wanted us to keep reincarnating as Roman soldiers, so that we would remain loyal to Rome and be more prepared for battles.

Like Hazel from the Percy Jackson book series, I had many past-lives and come back from the underworld, Hades many times. I am technically a walking dead and the undead shadow legionary, Damocles from the video-game, Ryse Son of Rome (metaphorically).

Also, the Romeo family possibly had many noble Romans who mastered sword-fighting, since they have a coat-of-arms with a sword.

My divine-father, Mars also knew that mortal parents these days weren't so good at raising Roman soldiers, so he sent the ghosts of my Roman soldier ancestors to raise me to be like them, since I was a young child.

All my ancestors are from Italy as far as I know: back to the 1800s and who knows where they were from, beforehand? The majority of them were most likely from Italy.

MY MORTAL PARENTS & FAMILY:

MY MORTAL FATHER:

My mortal father, Robert(o) is most like Mars. He's also very lazy, silly, stubborn and retarded (not that Mars is).

My mortal father is somewhat enthusiastic about The Roman Empire and shouts things like, 'Hail Caesar!', on the rare occasion.

He sometimes squeezes my bicep or shoulders, including after I help him move the heavy furniture and exclaims something like, 'Look at how strong your muscles are-Strong like a Roman soldier! You must have got it from your Roman soldier ancestors.' I guess that I not only got them from my Roman soldier ancestors, but my divine-father, Mars too.

Once, I dressed as a Roman soldier mascot with a red tunic and cheer-leaded for my youngest sister's red sports team, at the sports carnival, in primary school. (It must have been embarrassing for her. Sorry). Someone was staring at my Roman soldier costume and my mortal dad told them something like, 'Sorry. My daughter thinks she's a Roman.'

My dad is very talented at playing the drums. Ever since he was a youth, he could play the drums like a pro and drove our mums insane. My dad had a habit of banging the same war drum tune on the steering wheel and furniture like a bongo drum. I could always intuitively do the same and later play this tune on the drums, with little effort. I would quickly pick up on how to to play tunes on the drums just by listening to my dad playing them. I guess, I not only got my natural drumming skills from my divine father, Mars, but my mortal dad too.

Like the mortal father of the demigod daughter of Bellona, Reyna, in Percy Jackson, my mortal dad is also a psycho. And no, I am not psycho like him. On the rare occasion, he gets violent, very aggressive and threatens to kill, over small matters. I would never do that. He is often paranoid that everyone is spying on him and threatens to kill them. I am not that stupid either.

My dad has worked as a security guard for a short amount of times. He would like to be a police officer, but he wouldn't be mentally fit enough to be one. He would probably shoot innocent police and civilians over his paranoid thoughts.

Also, my dad had karate lessons and went to bootcamp, in his childhood. He is a black-belt in karate. My dad made a bow and arrow when he was a youth and shot an arrow into his brother's ankle. He chased my dad with a knife around the house for it. Luckily, he was stopped, before anything could happen, because then I might have never been born. He has also been to Rome and The Colosseum for a holiday when he was a kid. Maybe he saw the ghosts of our Roman ancestors there.

MY MORTAL MOTHER:

My mortal mother, Teresa is like the earth goddess, Gaia. Very motherly and loves admiring nature. She's very caring and goes out of her way to look after my family. Her name, Teresa even means 'farmer' in Greek, which relates to plants and hence Gaia.

Also, a large stress-head. She has an anxiety disorder and is a clean-freak. She's often shouts at us to clean the house and spends a lot of time cleaning it. She makes a huge deal over small matters. If anything goes wrong, she has a mental break-down and makes out like the apocalypse is happening.

When my mum was a youth, her brother accidentally shot her in the eye with a gun-leaving her permanently blind in one eye. Luckily, the bullet didn't penetrate her brain, because then I wouldn't have been born or maybe so, but not the same.

My divine father, Mars actually never bred with my mortal mother. Then, you might be wondering something like, 'Then, how are you a demigod? I thought that demigods are only children of a god and mortal who bred with each-other.' That is very wrong and a common misconception. In fact, demi means partial and not just half.

A demigod is any being with partial god status by definition. Having a god and mortal as a parent who bred together isn't the only way to be a demigod.

Basically, I was created as a female Roman warrior spirit by my divine father, Mars from celestial bronze and the soil on planet Mars, in my past-life. He genetically modified me to be a demigod (for the purpose of making me a submissive servant warrior of the gods with magical powers). I then incarnated as a mortal, on Earth, in order to complete a quest to gain immortality/godhood.

MY MORTAL SISTERS:

I get along with my second-oldest mortal sister, Briarna (meaning 'warrior' in Gallic) the best. We are like besties. Briarna is very outgoing, empathetic, hippy and generous. She's into vintage and spiritual stuff. We used to train in taekwando together and both have black-belt.

My third-youngest sister, Adria (meaning 'dark', in Greek) is very vain and mean. She has malignant narcissistic personality disorder. She often says mean things to my family and treats them like her slaves. I have learnt to ignore it and that has made me spiritually stronger.

My youngest sister, Chiara is very cute and mostly nice, but with a bad attitude when annoyed. Chiara gets irritated very easily. She's into Kpop, Korean culture and cute Asian things.

Chiara once dressed as a Roman wolf warrior and sung Romulus by the Roman metal band, Ex Deo. Another time, we made a film of us having a gladiator fight. I dressed as a gladiator and she dressed in her tiger onesie. We fought each-other in our spa, which we pretended was the Colosseum. Another time, she drew me funny memes of each Olympian god, including a picture of Zeus with the body of a goose. LOL.

Chiara also made me a voice recording of a legendary Roman speech that sounded something like the following:

'Thousands of years ago,

We ruled the world

And we fought for our victory.

We slaughtered the enemies-

Blood drooling from their bodies,

Until we were very pleased.

We raised our chalices and swords to our mighty Emperor

And we said, 'Be glorious!'

From that day on,

We were not only famous through the land,

But throughout the whole of time.

And that is how the legend goes, children.'

These times with Chiara I shall not forget. They were so hilarious. I still keep her funny Roman artworks, poems and videos, which she made for me in memory of them, after all those years.

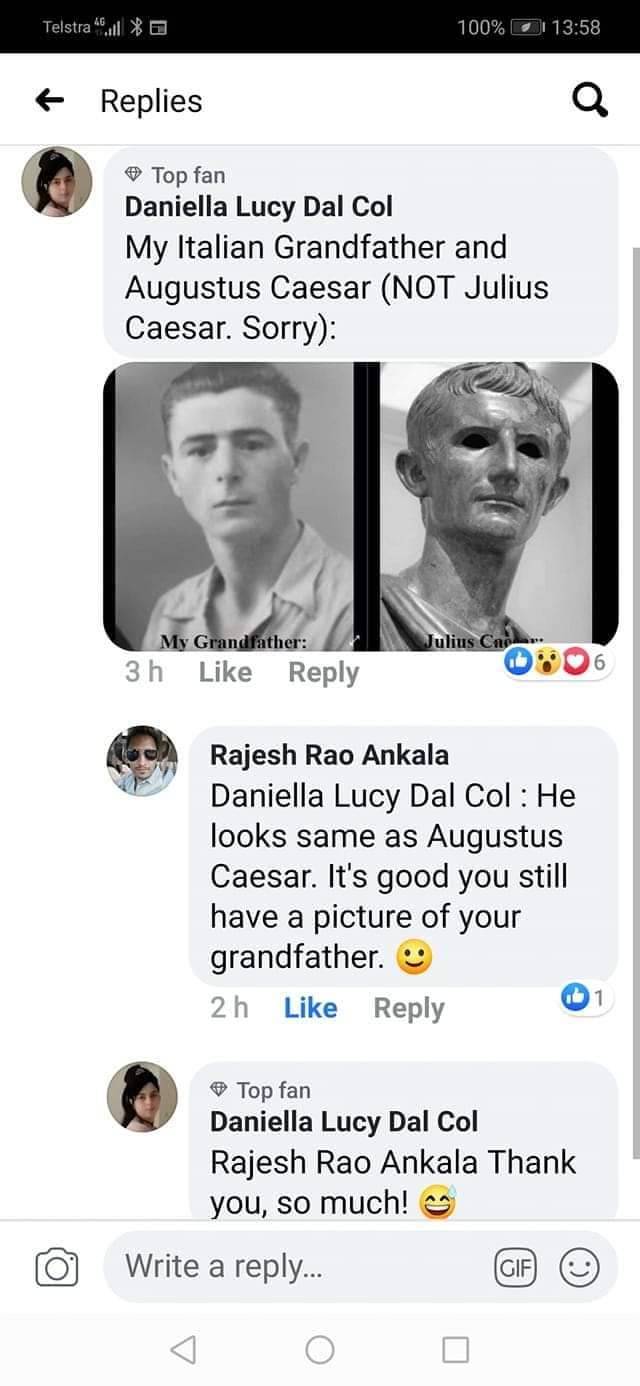

MY PATERNAL GRANDFATHER:

My paternal grandfather looked almost exactly the same as The Roman Emperor, Augustus Caesar. Perhaps, he descended from him or his relative. My grandfather's alter-ego was a navy and NAZI soldier. He would pretend that he's a navy soldier and say how spinach makes you strong like the cartoon character, Pop-eye, The Sailor's Man. Other times he would pretend to be a NAZI soldier, salute and exclaim, 'Hail Hitler!', (which I strongly object).

I would never even tell my close friends or family that I am a demigod daughter of Mars, because they are Christians, don't believe in these things and so would think that I am crazy. Also, because the gods demand that I keep it a secret for humility, secrecy, my reputation and other's sanity.

My Romeo family ancestors descending from the ancient Romans, my ancestry being almost fully-Italian, my great-grandfather being a policeman/soldier, my grandfather possibly descending from Augustus Caesar, my father being a black-belt Roman enthusiast and my family's military history, particularly its Roman one are some of the many reasons for why my divine father, Mars has favoured me to be the vessel of his incarnated demigod daughter's soul, Diana (my demigod-self). My imperial Roman blood is what makes me so Romanly and combined with my metaphysical DNA of my divine father, the Roman war god Mars, makes me double the Romaness. My mixed Greek, as well as Roman blood was also designed by Mars to give me double military prowess and help me negotiate peace between these cultures.

REFERENCE (Romeo family origin):

https://www.ancestry.com.au/name-origin?surname=romeo

NOTES:

-I think that Mars chose for me to be born in the new age, because it's the optimal time for me to work on one of my divine missions being to establish a new age Greek alien gods sect.

-I think that Mars sent me to be born into my mortal family not only on a quest, but also because they descended from the Romeo family, Roman soldiers, Roman demigod sons of Mars, in Rome and potentially Augustus Caesar. Also, because they inherited the rare dominant Roman gene in their bloodline.

-I think that Mars chose for me to be born in Australia, because much of the landscape here is like that on my home planet, Mars.

-I think that Mars chose the name of my street to be Alexander, after Alexander The Great and chose my house to be the one with the Greek neighbours, so I could be culturally influenced to be more Olympian.

-My divine father, Mars is Roman and my two mortal parents are Calabrian Italians. So, I am 33% (one third) god & Roman, as well as 67% (two thirds) mortal & Calabrian, in immediate ancestry. However, I feel 60% Roman & 30% Calabrian, in DNA/spirit as my godly Roman genes are more dominant, as well as intentionally overpowering and destroying my mortal genes, in an attempt to control my body to serve Rome.

I also inherit a rare unconquerable dominant Roman gene from my distant mortal Roman ancestors. The gene was created by Mars to ensure that someone would be a saviour of Rome & influence others to serve Rome for eternity. Only one person per generation inherits this special Roman gene. Those who inherit the gene are favoured by Mars as his demigod child. This is one of the many ways that I am a demigod.

Even though I am one third god, I am more powerful than the average demigod, because I was originally created as a semi-divine being by Mars to serve him/the gods and had no mortal parents. He infused my ichor (golden blood of the gods) with extraordinary powers & a super powerful burst of power that I can only use for a short periods in urgent times of need. I was then incarnated into a mortal on a divine mission. So, I am still a demigod as I am still semi-divine with a god and mortal parent.

-My paternal great grandfather ate mice like the ancient Romans, so maybe it was passed down from our Roman ancestors.

-All the original full-blooded Romans were a semi-divine race of mortals created, as well as genetically modified by Mars to serve him and advance humanity. So, all Romans were demigods. Those who descend from the Romans, including myself are Mars's legacy (demigod descendants). Mars's godly gene is the only unconquerable one that doesn't get diluted, even after thousands of years as it's super-loyal/overpowering & it seeks to dominate the body to ensure that Rome is served for generations/eternity.

-Having Roman genes from both my mortal and divine side of the family, I am super-powerful. The Romans were super-powerful soldiers. They were unconquerable. They conquered everything in their path. Nothing could conquer them or stand in their path. Nothing.

-Many of us demigods feel like orphans. We were abandoned by our godly parent and sent to incarnate as average mortals, also because they didn't want us. They are always too busy doing godly business to help and visit us. We are so neglected and abandoned that it's like we don't even have parents. We sometimes feel so unloved, betrayed, pathetic and worthless. We have to learn to be independent and survive on our own from a young age. We feel like our mortal parents aren't our real parents, but foster ones and that our godly parent is our real parent.

Our godly parent just incarnated us into the unborn baby of our mortal mother and left her to raise us, also because our godly parent was too busy to look after us. Our godly parent was hoping that giving us to mortal parents would give us a better chance at life than if they left us alone to starve to death, in a ditch. They also sent us to the mortal world, because they thought it would be a great opportunity to make mortal friends, learn to be a normal human, keep up with the trends, use the new technology, go out to fun places and other reasons.

-Many of us demigods have been getting new mortal parents, in each of our past-lives. We view our mortal parents as temporary and replaceable. We learn to accept that one day, they'll die and be replaced with new parents, in our next life. It's like an eternal cycle of being disposed and adopted.

-I have Greek toes when stretched out, but Roman toes when relaxed, so maybe my ancestors were mostly both Greek and Roman

-Many of us demigods view our mortal parents as alien and strange, because we are semi-gods and they are all mortal. Also, because mortals live, think and perceive differently from us. Why are they like that? We just don't understand these mortals.

-My parents told me about how teachers made students march around the school and sing the Australian anthem, before school everyday, in the old days. I would hate that, since I have no interest in Aussie culture and am sick of singing the Australian anthem, but would love it if it were Roman for obvious reasons. They told me that they had to march, while chanting, 'Left, left, left, right, left.' I would practise marching to this chant, infront of the mirror, before bed.

0 notes

Text

Tagging @unsuspecting-person specifically but none of you are safe from "oh I learned that from a friend who lives in that country/speaks that language :)"

i hope im not only a mutual to u but also someone u can refer to in conversation as ur friend from overseas so u appear worldly and well-traveled

#my family knows you as 'my italian friend' who i have ‘movie nights’ with (most know its anime lmao but still)#i dont have a lot of people im willing to call lmao so it caught their attention - and hearing that youre overseas they were all like :O#and they told my grandparents (whose parents were born in italy) and they were very excited#so anyway youve got several new englanders who are generally aware of you and think youre the coolest person ever 👍👍#(i mean theyre not wrong :))#and ive definitely shared information i thought was really cool or never thought of before and been like#aw yeah this is from a trusted source - we're pals#(sorry for being the loser american friend in return asdfgdf 💀)#funny

51K notes

·

View notes

Text

Of monuments and memorials...

I cannot imagine life without liberty, without the freedom to take a nap or road trip on my days off, or a life without days off, or work without a paycheck. I cannot imagine life without the security of knowing my family’s whereabouts because they had been sold to an unknown buyer…slavery.

I cannot imagine having no choices, and though mine haven’t always been sound ones, they were still mine to make (not to diminish the fact that as women, many of our choices have been hard-won, some during my lifetime, and some of those battles still rage because of old white men.)

I cannot imagine living in fear and uncertainty because of the color of my skin, of being considered less than a human being. Even in the face of a largely misogynist work and social culture, I have never feared dying at a traffic stop. I know men who do, and I also fear for them.

I am among the blessed, for even as impoverished as my ancestors were, they were autonomous and free to seek new opportunities. Even those who worked in dreadful feudal circumstances were not property. I have been a daughter, a wife, a mother, an employee, but never property. I cannot imagine a life as property. Slavery…

…such recent history.

I knew my maternal great grandmother; we called her “Nonna Vecchia” and she fascinated me. Teresa Gandini was born in 1874, only a few years after the unification of Italy. Italy has been one nation with a common language for only a century and a half. That’s great-grandparent history, and because I knew mine, it feels pretty recent to me.

My husband’s great grandfather Lewis was born in 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War. His childhood was marked by the absences of his father and uncles who were soldiers on both sides of that conflict, and Lewis grew up in the days of reconstruction and the movements that followed. That is not ancient history. It is recent...great-grandparent history.

Many of us learned the stories told by our great-grandparents and grandparents, and the family lore that gets passed down by our parents who shared the oral histories with our children we will share with our grands. My great-grandmother’s little shack was gone long before I ever met her, but the stories were so vivid that I swear I can smell the smoke from that fireplace at the end of a long day in the fields. I can feel the hunger during the lean times, and I am still angry at the way the Lavellis mistreated my family. That history is in my bones. It is cellular. It is part of who I am. Am I the only one with a sense that we can reach back and almost touch those family memories?

In 1905 America anyone over forty had been born during the Civil War. In the South, they would have been born in a slave state, which means black people of that generation had most likely been born into…slavery. Those are the great-grandparents of my generation, and their bondage is part of the family history to which my friends can reach back and almost touch. That is recent, fresh, and I would find it still pretty damn painful, because...great grandparents.

In 1905 Alabama the grip of Jim Crow was a tight one, and the mistreatment of people of color was not only largely ignored, but at times encouraged. The idea that black people were somehow inferior and should not be allowed a place in white society was a driving force behind the laws of the day. Those who had been freed from slavery were still working forty years later, struggling to build their lives within a community that was powered by those who once owned them and against a deep-seated resentment of having to relinquish that “peculiar institution.” Some moved away, but many remained…great-grandparents.

In 1905, the business of living often required a trip downtown where segregation and inequality were celebrated on every corner by signage directing “colored” folks to the rear and away from “whites only” amenities. Renewing a license or paying a tax meant visiting the courthouse and required a cautious approach for those relegated to back entrances and back seats…great-grandparents.

In 1905 the Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument on the courthouse square:

"In memory of the heroes who fell in defense of the principles which gave birth to the Confederate cause erected by the Daughters of the Confederacy. Our Confederate dead. In memory of General John Hunt Morgan, ‘Thunderbolt of the Confederacy, born in Huntsville June 1, 1825, died defending the noble cause Sept. 1864’”

Read that again:

“In defense of the principles which gave birth to the Confederate cause…”

No matter how many have tried to shift the narrative, that “cause” was the fight for states’ rights to own human beings for the purpose of doing the work and building the infrastructure that established the wealth of an economy which enabled southern white society to flourish. Simply put…slavery.

Having lived the other side of that sentiment, those former slaves understood all too well. Imagine having to walk past that memorial to the very men who bought and sold you, and who fought for the right to own you and yours, and whose legacy still required you to use the back entrance or walk an extra block to find a “colored” bathroom. In 1905, I imagine that newly erected granite insult stoked the fires of more than forty years of still-fresh memories, oral histories which were shared at family dinner tables and on front porches by the very generation who lived them, former slaves…great-grandparents.

Today the Madison County courthouse still sits on the square, though the old columned structure has been replaced with stark modern architecture, and that old Daughters of the Confederacy monument to the defenders of the “cause” still stands. We still have to go downtown for the business of life, and the great-grandchildren of slaves are still faced with that granite memorial to the men who fought to keep their beloved ancients as property.

Consider how it feels for them to see these public monuments to the efforts of men who fought for the “cause,” and how insulting it is to see people still fighting for the protection of that sentiment. Imagine how it feels to hear people you thought were your friends arguing to preserve a monument to the men who fought to enslave your great-grandparents. The signage of segregation may be gone, but we are daily reminded that our society still has much work to do to ensure everyone is safely included within it. It is long past time for that thing to be in a museum instead of the town square, and for society to recognize the truth of the “cause” for which it is displayed.

Reconstruction may have begun in earnest, but it lost it’s way too soon, and here we are, the great-grandchildren, still on both sides of the struggle to put things aright. We have a responsibility to correct the myth of the “cause,” while we still have voice, especially if we are white. We will soon be the great grandparents telling stories at dinner tables and front porches...oral histories.

As for those whose great grandparents were defenders of the “cause,” they left behind some valuable lessons. We can teach the wrong side of history without celebrating it. As for monuments and memorials...we all have skeletons in our family closets that should not be commemorated on the courthouse square.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Life through a lens

Words Colin Richardson; Photo Joe Magowan

To call Helena Appio a documentary film-maker would not be a lie, but nor would it be anywhere near the whole truth. At various times, she has been a student of anthropology, art, fashion and textiles; designed fabrics and clothes; modelled for Laura Ashley; and been a college lecturer.

During her training as a producer at the BBC, she had a brief sojourn in the land of sticky-back plastic. To her embarrassment, she once turned down the scourge of soggy bottoms. And don’t get me started on her byzantine and extraordinary family history. Well, do, otherwise the next paragraph will have to go out of the window.

In the early 1900s, great-grandfather Appio left his home in southern Italy and moved to Sierra Leone. ‘I expect he left Italy to escape poverty and make a better life for himself, but how and why he ended up in Sierra Leone, I don’t know,’ says Helena.

But once there, he did something even more unexpected. He opened a cinema, the first in Sierra Leone and probably the first in all west Africa. Helena wishes she knew more about it, but ‘the records were destroyed in the civil war of the late 90s and early 2000s. I’d like to go there to see what I can find out, but some of my relatives who have been say there’s nothing to go on.’

Great-grandfather married a local creole woman, part African, part Chinese and they raised a family together. One of his sons later moved to Nigeria, where he also opened a cinema. He, too, married a local woman, but he was killed in a motor accident shortly after the birth of their first child, a son. The boy, Helena’s father-to-be, was taken by his grandparents to live with them in Sierra Leone. He didn’t see his mother again until he was 15.

As a young man, Helena’s father travelled to Britain to train as an engineer. One evening, at a dance, he met the adopted daughter of a wealthy Glasgow family. They married and she went back with him to Nigeria, which, as Helena says, ‘was a very bold thing to do in those days.’

Helena, the eldest, one of her two sisters and her brother were all born in Nigeria (her youngest sister was born in London). But after ten years, her parents’ relationship, it seems, had run its course. Helena’s mother moved to London, bringing her children with her.

‘But my father didn’t come back with us. They never spoke about it, but they must have split up at that point. My mother just said we were all coming back to go to school, which we were. My father came and visited three or four times a year, as he was often in Europe with his business.’

The family settled in Blackheath. They were an unusual sight. In the mid-1960s, there weren’t many white women with black children living on the Heath. ‘People kept stopping my mother because they thought she must be Peggy Cripps,’ says Helena.

Peggy Cripps, the daughter of Labour grandee Sir Stafford Cripps, had caused something of a sensation when, in 1953, she had married the radical Ghanaian lawyer and politician Jo Appiah. The Appiahs had four children – three girls and a boy – who were roughly the same age as Helena and her siblings.

Helena went to Blackheath High, which wasn’t always a comfortable experience as she and her sisters were the only black pupils there. But she did well and, after leaving school and taking a gap year (partly spent travelling in Brazil), she went to Durham University to study anthropology.

‘I found myself in a very old-fashioned college. You had to be in by ten o’clock in the evening and every week there was a formal dinner where you wore a black gown and stood when the head of the college came in. I did not like that.’

So she moved back to London and switched her studies to art. ‘I’d always been very good at art,’ she says, ‘but it wasn’t encouraged at Blackheath High, which was a very academic school.’

She took foundation courses in art before switching to a degree in textiles and fashion at Middlesex University. After graduating, she opened a clothes shop in Covent Garden, selling fabrics and clothes she designed. But when her daughter was born, it became too much and she swapped the world of retail for the more sedate world of lecturing.

‘Then, one day, I saw an ad in the paper – the BBC was looking for nine people to be trainee directors and so I applied. We had two or three interviews and I got one of the places. I learned later that there were over 1,000 applicants. If I’d known that at the time, I wouldn’t have applied; I’d have thought there was no point. Nowadays, I’m often asked to talk to students and I tell them, don’t be put off; it’s worth a try, you’ve got nothing to lose.’

She started in 1990, a year after the birth of her son. Her training included a stint working on Blue Peter, making short filmed inserts. She says she learned a valuable lesson. No, not how to make a nuclear reactor out of some old washing-up liquid bottles, the insides of several loo rolls and acres of Fablon, but how to tell a story in just a few minutes.

It stood her in good stead when she was offered a contract in the BBC’s documentaries department. She worked on many programmes in her time there, but one that stands out for her is DJ Derek’s Sweet Memory Sounds, a portrait of the late Bristolian DJ who was known as ‘the blackest white man in Britain.’

After nearly ten years at the BBC, Helena decided to strike out on her own as an independent producer. She made two memorable documentaries. The Windrush Years for Channel 4 was a series of 12 three-minute portraits of people who came from the Caribbean to live and work in the UK between 1948 and 1971.

A Portrait of Mr Pink told the story of one of Lewisham’s most remarkable citizens, whose vividly painted house at the top of Loampit Hill dazzled all who passed it. More recently, Helena for the Kurdish Memory programme, helping to document the lives of the Kurdish people of Iraq.

Three years ago, Helena left Peckham to live in Hong Kong when her husband got a job working in the acquisitions team at M+, a new museum for visual culture being built in West Kowloon. She is working on a new film of her own, a documentary about the Filipino women who work, often in terrible conditions, as domestic servants in Hong Kong.

But she is back in Peckham whenever she can, visiting friends and seeing her children: Chris, a personal trainer, sports masseur, musician and DJ (performing as Jean Frais); and Nina, a charity worker, who is also the Queen of Samba, performing with the Bermondsey-based London School of Samba.

Helena has but one major regret in life. When she was working in the commissioning department at the BBC, she was approached with a programme idea by an unknown baker. Paul Hollywood, for it was he, invited her and some friends to his bakery school in an effort to convince her to give him his break into TV.

‘It was very nice,’ says Helena. ‘We had a good time. But I couldn’t see what we could do with him, so I turned him down. It took a stroke of genius by the Great British Bake Off people to team him with Mary Berry, Mel and Sue and make him the bad guy. I feel like the person who turned down The Beetles.’

..........................

View DJ Derek’s Sweet Memory Sounds at vimeo.com/53691544 and read about Mr Pink in the August/September issue of our sister paper, The Lewisham Ledger

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Padre Pio Inspirational Story

With Image:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/padre-pio-inspirational-story-harold-baines-6435857720028524544/?published=t

Father Pio Francesco Mandato, F.M.H.J., was born in Italy in 1956, and his parents and grandparents were from Pietrelcina, Padre Pio’s hometown. Father Mandato’s family members, including his great-grandfather, received many graces from their spiritual father, Padre Pio. His grandmother, Maria DeNunzio once asked a friend who was going to San Giovanni Rotondo to deliver a letter to Padre Pio. She fixed her friend a cup of espresso, and they had an enjoyable visit. Then he left for the monastery. He was able to talk with Padre Pio and when it was time to say good-bye, Padre Pio surprised him by saying, “Aren’t you forgetting something?” “Not that I can think of,” Maria’s friend replied. “Not only did you enjoy a cup of coffee and a visit with Maria, but you promised her that you would give me the letter that is in your back pocket!” At once he remembered and quickly placed the letter in Padre Pio’s hands.

In Pietrelcina, everyone called Padre Pio, Il Monaco Santo, the holy friar. The townspeople loved to exchange stories about their experiences with Padre Pio. Everyone felt very proud that the “holy friar” was a fellow citizen of Pietrelcina. The people from Pietrelcina were characteristically simple, devout, hard-working, and strong in their Catholic faith. Many people in the area were related or distantly related to each other. Pio Francesco’s mother was related to Padre Pio through her paternal grandmother.

Padre Pio never forgot the town from which he had come. He loved Pietrelcina and he loved the people who lived there. He said that he remembered Pietrelcina, “stone by stone.” In a letter to his brother Michael, who still resided there, Padre Pio wrote, “Pietrelcina is totally in my heart.” Regarding his spiritual life, Padre Pio once said, “Everything happened in Pietrelcina. Jesus was there.” It was in Pietrelcina that the Lord began to pour out his graces on the young Capuchin. Once Padre Pio made this prophetic statement, “During my life I have cherished San Giovanni Rotondo. After my death I will cherish and favor Pietrelcina.” How fitting that today he is known as St. Pio of Pietrelcina.

During World War II, the people of Pietrelcina were worried about their safety. “Do not worry,” Padre Pio said. “Pietrelcina will be protected.” History bears out the truth of his statement. Padre Pio was transferred to the Capuchin monastery of Our Lady of Grace in San Giovanni Rotondo in 1916 and remained there until his death in 1968. A number of the residents of Pietrelcina moved to San Giovanni Rotondo to be closer to their spiritual father.

Once Paris DeNunzio, Pio Francesco’s grandfather, made a trip to San Giovanni Rotondo from Pietrelcina to see Padre Pio. The road that led up to the monastery was steep and dangerous. Paris’ companion, who was driving, fell asleep at the wheel and the car swerved and veered off the road. Paris, who was very frightened, began praying, “Padre Pio, helps us!” At the last moment, the driver was able to gain control of the car. When they arrived at the monastery and went to Padre Pio’s cell, Paris told his spiritual father about the near accident. “And were you frightened, Paris?” Padre Pio asked. “Yes, I was frightened,” Paris replied. “Well, don’t you know who was driving?” Padre Pio asked. Paris asked him what he meant. “I was driving the car,” said Padre Pio, “and you all arrived safely!”

Paris used to pray daily to Padre Pio, recommending to him his wife, his daughter, his son and other family members. Once when he was talking to Padre Pio, he asked him to pray for his family and began to name them. Padre Pio said to him, “You do not need to tell me their names. I hear their names every day in your prayers.” Another time, Paris was experiencing pain in his chest and was worried that perhaps he had heart trouble. He told Padre Pio about it and Padre Pio replied that there was nothing wrong with his heart. “Of course there is something wrong,” Paris said. “If there wasn’t something wrong, I would not be in so much pain.” Padre Pio told him to stop talking about it. “If you don’t stop, I will give you a punch,” Padre Pio said. He then gave Paris a light punch on his chest. From that moment on, he never experienced another pain in his chest.

Pio Francesco’s mother, Graziella, first met Padre Pio when she was ten years old, when she traveled with her father, Paris DeNunzio, from Pietrelcina to San Giovanni Rotondo. They found Padre Pio inside the 16th century friary church of Our Lady of Grace, surrounded by a group of people. Being small, Graziella was unable to get close to him. She could only see the top of his head. When Padre Pio saw Graziella, he extended his arm over the people, and allowed her to kiss his hand. His eyes made a profound impression on her, an impression that she would not forget.

In 1946, a few days before Christmas, Graziella and her brother visited the monastery and Padre Pio blessed Graziella by placing his hands on her head. Then, in his paternal way, he gave her a fatherly embrace. At once, she became aware of the beautiful scent of roses. She believed that the fragrance was coming from the wound in his side.

One time Graziella told Padre Pio that she had met a man she was thinking of marrying. “Don’t do it. He is not for you. You don’t know what kind of coat he wears,” Padre Pio said to her. She and her father did a little research and found out that the man was a communist. When she inquired about a second suitor, the answer was again a firm “no.” When she finally named a third man, Andre Mandato, Padre Pio said, “The angel of God has passed. Do it with the blessing of God.” She married Andre in 1955.

Because of the popularity of Padre Pio’s confessional, a booking system had to be put in place at the monastery. People would take a ticket and wait for their number to be called. It sometimes required a wait of eight days or more. Once Graziella had a tremendous desire to speak to Padre Pio. The way to speak to him was through the vehicle of the confessional but Graziella did not want to wait that long. She somehow had the courage to approach the confessional without a ticket. The woman at the front of the line told her she could go ahead of her.

Just as she stepped into the confessional, Padre Pellegrino, Padre Pio’s assistant, whose job it was to check tickets, told Padre Pio that Graziella had just entered without a reservation. Padre Pio said to him, “And when she did, who were you watching?”

Graziella was permitted to make her confession regardless and she told her spiritual father that she and her husband were expecting their first child. “You will have a son,” he said. “Name him Pio Francesco.” When her baby boy arrived on July 6, 1956, she was delighted that he shared not only Padre Pio’s baptismal name, Francesco, but also his name in religion, Pio. Padre Pio sent his blessing as well as a medal with the Blessed Virgin on one side and St. Michael the Archangel on the other.

Pio Francesco Mandato was four years old when his grandfather, Paris, took him for the first time to see Padre Pio in his cell. Padre Pio blessed little Pio Francesco and embraced him. Little Pio came just up to the middle of Padre Pio’s waist. Afterward, he told his mother, “Padre Pio has perfume on his tummy.” Graziella told her son that he did not wear perfume. He had perceived the characteristic fragrance of Padre Pio, wholly supernatural in origin and most frequently a sign of grace.

Paris took little Pio Francesco with him a number of times to the monastery to visit Padre Pio. The men were allowed to go into a gathering area and converse with Padre Pio. Women were not allowed. Pio Francesco remembers what joyful occasions they were for all concerned. In the presence of a number of Capuchins and laymen, Padre Pio enjoyed the fellowship and he loved to tell jokes and to make his friends laugh.

Seven year old Pio Francesco and his younger brother Vincent received their first Holy Communion from Padre Pio on October 3, 1964, on the feast of the Transitus of St. Francis of Assisi (the celebration of the death of St. Francis of Assisi). Afterward Padre Pio said to the young boys, “I pray that your last Holy Communion will be even more beautiful than your first.” Pio Francesco remembers the solemnity and the great devotion with which Padre Pio celebrated Mass. Although his Mass was long, the time seemed to pass very quickly. Another remarkable aspect of Padre Pio’s Mass was that although it was always very crowded, a profound silence pervaded the church.

The Mandato family emigrated to the United States in 1964 and settled in New Jersey. Naturally, they missed Padre Pio immensely. Father Alessio Parente, Padre Pio’s secretary, relayed a message to Graziella from Padre Pio. He said, “Tell Graziella that I always have her present in my prayers and I am united to her whole family.”

On September 22, 1968, Graziella had a vivid dream of Padre Pio. “I come to say goodby to you,” he said. She said to him, “Don’t leave,” and he replied, “The Lord is calling me.” The next day Graziella learned that he had passed away in the early morning hours.

Following in the footsteps of his spiritual father, Pio Francesco Mandato was ordained to the priesthood in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1985. He and his family made a trip to Italy so that he could celebrate his first Mass in Pietrelcina at the Madonna Della Libera altar (Our Lady of Liberty), at Our Lady of the Angels parish. It was the very same church and altar where Padre Pio had celebrated his first Mass on August 14, 1910.

Today, fifty year old Father Pio Francesco Mandato, F.M.H.J., belongs to the Franciscan Missionary Hermits of St. Joseph and lives in Eastern Pennsylvania. He continues to live out his priestly vocation in the spirit of St. Francis of Assisi. He feels that Padre Pio is still guiding him and helping him on his spiritual journey. “More than anything else, I remember Padre Pio as a very loving man, like a loving father,” Father Pio Francesco said. The words that Padre Pio said to his mother so many years before remain a consolation to him, “Tell Graziella that I always have her present in my prayers and I am united to her whole family.” Father Pio Francesco Mandato continues to carry on the work of the Lord.

1 note

·

View note

Text

What A Badass Olympic Skier Can Teach Us About Work-Life Balance

Team USA has sent 20 fathers to Pyeongchang, but only one mother: Kikkan Randall. A three-time winner of cross-country skiing’s World Cup sprint title, Randall was part of a baby boom that happened after the 2014 Sochi Olympics, when four of the sport’s top athletes took time off from racing to give birth.1

These women didn’t just return to work — they came back to the highest level of a demanding sport, and all four are expected to compete in Pyeongchang. But Randall is doing so without the same safety net that her European colleagues have. And that’s left her facing the same challenge that many other American women experience: how to balance a grueling career with the demands of new motherhood. A job as arduous as being a professional athlete (or, say, director of policy planning at the State Department) has little room for compromise or scaling back, and that means that much of the parenting must fall to a spouse or outside help.

The 2018 Games will be the fifth Olympic appearance for Randall, a 35-year-old cross-country skier from Alaska.2 In 2008, Randall, nicknamed Kikkanimal, made history by becoming the first American woman to win a World Cup in cross-country skiing. And in Pyeongchang, she has a legitimate shot at a medal.

youtube

Mothers-to-be in most professions take time off after childbirth, but Randall’s situation was different: “I was on my maternity leave while I was pregnant,” she said. Because she remained on the U.S. ski team roster, she retained access to her health insurance, and most of her sponsors continued their support, in exchange for appearances, social media plugs and other publicity. She resumed training about three weeks after her son, Breck, was born in April 2016, with the support of her husband, Jeff Ellis, who parented while she trained. Having a husband who is willing to take on parental duties and, most importantly, to do so “unbegrudgingly” has been “a huge piece of the puzzle,” Randall said.

There’s no such thing as a part-time return to work in elite sports, which usually require multiple training sessions each day, along with naps, massages, full nights of sleep and other recovery rituals. Of course, sleepless nights are almost a given for the first years of a child’s life. And Randall said that knowing Ellis will “take care of those night-time wakings before a race really helps.”

She noted that her peers in Scandinavian countries have the benefit of paid time off for fathers as well as mothers. (Of the 35 countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. is the only one without paid maternal leave.)

Paid maternal leave policies around the world

Among countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2016

Country Length of paid maternity leave, in weeks 1 Greece 43.0

–

2 United Kingdom 39.0

–

3 Slovakia 34.0

–

4 Czech Republic 28.0

–

5 Ireland 26.0

–

6 Hungary 24.0

–

7 Italy 21.7

–

8 Estonia 20.0

–

9 Poland 20.0

–

10 Australia 18.0

–

11 Chile 18.0

–

12 Denmark 18.0

–

13 New Zealand 18.0

–

14 Finland 17.5

–

15 Canada 17.0

–

16 Austria 16.0

–

17 France 16.0

–

18 Latvia 16.0

–

19 Luxembourg 16.0

–

20 Netherlands 16.0

–

21 Spain 16.0

–

22 Turkey 16.0

–

23 Belgium 15.0

–

24 Slovenia 15.0

–

25 Germany 14.0

–

26 Israel 14.0

–

27 Japan 14.0

–

28 Switzerland 14.0

–

29 Iceland 13.0

–

30 Norway 13.0

–

31 South Korea 12.9

–

32 Sweden 12.9

–

33 Mexico 12.0

–

34 Portugal 6.0

–

35 United States 0.0

Source: OECD Family Database

Randall’s Finnish peer Aino-Kaisa Saarinen had a child around the same time that Randall did, and she told me that her country has a mandatory four-month paid leave for mothers, which she started a month before her due date. After the baby was born, she and her partner received further benefits, including leave that they could split as they chose between the parents. “In our case, the dad took all that,” Saarinen said. (Not to mention the paid leave that fathers are entitled to.)

Randall has competed in the predominantly Europe-based World Cup without that kind of paid leave but with Breck in tow for the past two seasons. It hasn’t always been easy. Although she emerged from childbirth without any serious complications (not all women do, as tennis star Serena Williams’s story demonstrates), the snap in her muscles didn’t return right away. And during her time off, the U.S. team “had gotten so strong,” Randall said. She sat out the second World Cup weekend after her return because she wasn’t skiing as well as her teammates.

There have been many men who’ve continued competing after adding a child to their family, said Chris Grover, head coach of the U.S. cross-country ski team, but very few women. “Many of these guys are not primary caregivers and tend to come to the races Thursday and head back home on Sunday night or Monday,” Grover said. And while fathers may experience sleepless nights just like mothers do, they don’t need to physically recover after childbirth.

Randall and her husband have built their work and family life around her job. Ellis secured a job as a media coordinator for the ski federation, which allowed him to travel the World Cup circuit with her. “He got the job so that we could see each other in the winter,” Randall said.

Randall breast-fed her son until about a month into the racing season. Realizing that there would be at least four mothers coming to the World Cup with babies, the ski federation worked with the athlete commission, national ski federations and organizing committees to make formal recommendations encouraging race venues to provide a “baby room” with appropriate provisions so that moms can breast-feed and care for their infants as needed. Randall thinks she used these rooms much more than others in her cohort of new mothers. She said that may be because the others live in Europe, where most of the races take place, and can travel back and forth between home and races on a weekly basis.

In Finland, Saarinen benefits from laws that guarantee child care facilities will be available. “The government also pays for most of it,” she said. That’s not all. “We also get child money from the government, which is about 200€ per month, a baby box with 48 items, and free and mandatory monthly health checks for baby and for the mom.”

Things are different in the U.S. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, 62 percent of parents of infant or preschool-age children report difficulty finding affordable, high-quality child care in their community, regardless of their income.

Because Randall and Ellis are both working while on the race circuit, their parents and some friends have stepped in to provide child care, but paying travel and accomodations for these helpers isn’t cheap. In part because of the cost, Breck won’t be accompanying his parents to Pyeongchang. After calculating that it would run something like $15,000 to $20,000 for them to bring him and a caretaker along, they decided to send him to his grandparents’ house in Canada instead.

As well as things are working out for her now, Randall acknowledges that her current situation is not sustainable. And it probably wouldn’t be scalable to the whole workplace either. Grover acknowledged that it’s difficult to imagine a ski team traveling around Europe with all the coaching staff’s kids, in addition to the team athletes.

Randall plans to retire from racing after this season but will remain in the sport. She is president of the U.S. branch of Fast and Female, a group that encourages girls to participate in sports, and she’s running for election as an athlete representative on the International Olympic Committee Athletes’ Commission. After two decades of competition, it feels right, she said. Success in a career like sports requires giving it your all, and that means family life can’t always come first. For a parent who wants to substantially take part in parenting, eventually something must give.

from News About Sports https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/what-a-badass-olympic-skier-can-teach-us-about-work-life-balance/

0 notes