#and there is a trend towards adopting laws and regulations related to minors online

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

If you're following KOSA, you should also be following state legislation, which is much more rapidly adopting tech regulation related to child safety than Congress. For reference, in 2023, 13 states adopted 23 laws related to child safety online.

Even if your locality hasn't adopted similar tech regulation, online platforms, apps, and websites are rarely operating in only some states. When regulations become patchwork, it's often easier for companies to adopt policies reflective of the most stringent regulations relevant to their service for all users, rather than try to implement different policies for users based on each user's location.

I know this because that's what happened when patchwork data privacy regulations began swelling — which is why many webites have privacy policies reflective of the GDPR that apply even to users outside of Europe. I also know this because I'm a tech lawyer — I'm the wet cat drafting policies for and advising tech and video game companies on how to navigate messy, convoluted, and patchwork US regulatory obligations.

So, when I say this is how companies are thinking about this, I mean this is how my coworkers and I have to think about this. And because the US is such a large market, this could impact users outside the US, too.

#kosa#us law#tech policy#data privacy#regulatorycompliance#sorry if i tricked you into thinking this is a fandom account#this is just my blog of twelve years#and ive seen a lot about kosa#but local us legislation is where most of the movement here is#and there is a trend towards adopting laws and regulations related to minors online#that is rapidly gaining momentum#i love being an internet lawyer but i also love the internet#and so im feeling more and more compelled to talk about how the tectonic plates are shifting fast

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

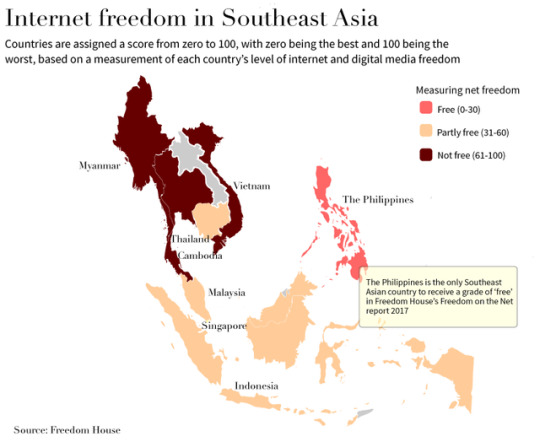

The Philippines is the only Southeast Asian country with a ‘free’ internet grade, report finds

In the annual Freedom on the Net report, more countries around the world were seen to be using fake news and online manipulation than ever before

Freedom House published their annual Freedom on the Net 2017 report where they assess the internet access and online censorship of 65 countries from around the world. Overall, the trend leaned towards more countries using fake news to manipulate online content and within Southeast Asia there was only one country that came out with a ‘free’ grade (Freedom on the Net gives countries a grade based on zero to 100, with zero being the best and 100 being the worst; a free grade is any mark below 30).

For Madeline Earp, the editor of the Asia portfolio of the Freedom on the Net report, which oversaw the study of 15 countries from across the continent and eight from within Southeast Asia, these overall findings – though disappointing as a whole – were not surprising.

“It [did] however surprise me that few countries improved based on access, which is expanding really rapidly in Southeast Asia,” Earp said in an interview.

One of the largest concerns that Freedom House, the US-based independent watchdog that conducts this annual report, pointed out in their findings was that though it may initially seem worth celebrating that countries in Southeast Asia are witnessing this huge surge in accessing information online and using the internet to share that knowledge, we should also bear in mind that this will likely lead to more opportunities – as this report shows – for people to be arrested and imprisoned for their online activities.

“That’s a really worrying development, and shows how laws that undermine free speech can be abused to offset the benefits we associate with accessing the internet,” Earp added.

Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines are all the Southeast countries profiled in this report. Beginning with the countries that fared the best, we asked Earp to take us through each Southeast Asian country assessed and discuss some of the more interesting findings from each region.

The Philippines: Score: 28 (Free)

The Philippines received a grade in the Freedom on the Net report that granted them the distinction of being the only Southeast Asian country with ‘free’ internet (marks that were between zero to 29 were considered to be free and the Philippines barely scraped by with a grade of 28).

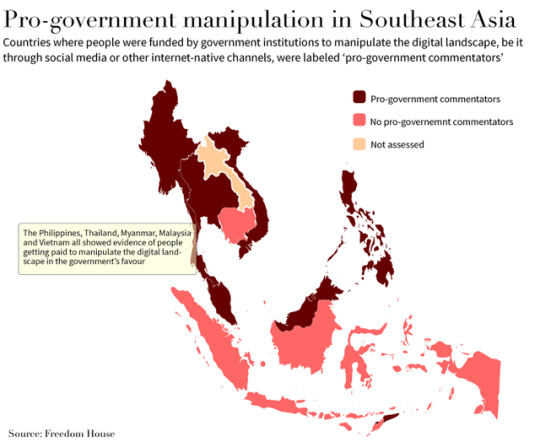

But despite this singling out, the research analysts at Freedom House found that the Philippines – among 30 other countries in the report – were one of the worst offenders when it came to manipulating online content through paid sponsors of the government. These people act as organic voices online, but are in fact paid ‘opinion shapers’ of the government who are working to spread agendas, particular points of view or even completely shut down the opposition.

Earp used the success of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s presidential campaign in 2016 as a shining example of just how influential these social media ‘opinion shapers’ can be.

Though Duterte had a smaller budget to work with than his opponents, he directed most of these funds towards social media campaigns, people who came to be known as a ‘keyboard army’. The report described how members of this online army could earn anywhere from $10 to $60 a day for operating one of these fake social media accounts.

“Clearly, online information in Southeast Asia can have a massive reach, which is positive,” she said. “But,” she added, “there is a real need for digital literacy and security training to protect people online and help us all identify and overcome invisible influence operations.”

Singapore: Grade: 41 (partly free)

Though Singapore’s status is temptingly close to being considered free, falling short by only 11 points, Earp believes that things are expected to only get worse for online expression in a city-state already known to have very little press freedom.

“While activists from grassroots campaigns were early adopters when it came to digital communications, it’s clear that governments are catching up,” she said. “Authorities in countries with extensive press controls like Malaysia and Singapore, for example, are exploring ways to regulate digital news platforms, too.”

Examples of this increased regulation can be seen playing out in cases like the one of teenage blogger Amos Yee, who was sentenced to six weeks in prison for his online criticism of religious groups. And then again with the founder of the site the Real Singapore, who received a ten-month sentence for arousing what the court characterised as racial sentiments on his site.

As it stands, Singapore has no right to privacy and it is commonly accepted that even your private conversations on the internet can be monitored by the government, the report found. One analyst from the UK was quoted in the report as describing the current state of affairs as such:

“Few doubt that the state can get private data whenever it wants.”

Malaysia: Grade: 44 (partly free)

Malaysia had an overall score of 44 out of 100 and though that makes them to be considered to be partly free when it comes to internet freedom, their scoring for internet freedom has been generally on the decline since 2011 when they had an overall score of 41.

What spared the country this year from falling even lower in the ranks was their ability to improve overall internet accessibility, with both internet penetration and internet speed increasing significantly in comparison to previous years.

“The only Southeast Asian country that registered an improvement this year was Malaysia, and that was specifically because of expanding access,” said Earp.

However, despite this ‘improvement’, Earp believes this is hardly an occasion to begin celebrating Malaysia’s net freedom.

“Dozens of people still face criminal charges for online speech, and the government censored news reports about corruption for the second year running, though it had pledged never to censor the web—so it’s hardly a resounding success story.”

The government didn’t offer any new blocks on websites or blogs, but they do continue to have a ban on popular sites from posting content related to Prime Minister Najib Razak’s corrutption scandals. For instance, popular international sites like Medium,Sarawak Report and the Asia Sentinel remain blocked for Malaysians as of 2017.

Internet users, more specifically ones who post criticisms of the government on their Facebook page, are commonly arrested and prosecuted for online speech. During the time that the report was filed, at least one person in Malaysia had been sentenced to one year in prison. Muhammad Amirul Azwan Mohd Shakri, 19, is serving out a one-year sentence for 14 counts of posting to Facebook with comments that were critical of the Sultan of Johor.

There is concern, the report warned, that for the upcoming 2018 election there could be an increase in the cracking down on internet freedom, specifically for online voices who may decide to take a critical stance of the government.

Indonesia: Grade: 47 (partly free)

Internet freedom is important everywhere, but within Southeast Asia, Indonesia could prove to be one of the world’s most important users of the world wide web, as they are set to be the fourth largest online user by 2020.

There are currently 43,000 online media outlets in Indonesia, which has lead to a decline in the standards of online news reporting and a tailwind rise of fake news. Most of the focus of this fake news reporting has been targeted at ethnic and religious minorities, with the overarching goal being to legitimise their existence.

‘The Ahok effect’ was an unfortunate trend from Indonesia that stemmed from the arrest of a Christian governor who had been allegedly misrepresented in a viral video that showed him slamming Islam. Following his arrest, many right-wing groups began to congregate online to harass and, in some instances, take their harassment offline against people who they perceived were insulting Islam on social media.

“In Myanmar and Indonesia, for example, fake news reports targeted religious and ethnic minority groups in spite of official efforts to curtail hate speech.” (pull quote)

As a reaction to this ‘Ahok effect’, the government took measures to decrease internet freedom by amending the Law on Information and Electronic Transaction (ITE), which ultimately empowered officials to block online information and punish people for online defamation. This law failed to curb online manipulation and defamation, but did lead to a number of long detentions and prison sentences that have been widely criticized.

Cambodia: Grade: 52

Cambodians are growing to rely on the internet as one of their main resources for receiving news, with some people saying they were more likely to consult the internet before other traditional news outlets, the report found.

Considering the large number of traditional media outlets who are influenced or entirely controlled by the government, the country’s pivot to the internet does point to a positive shift. But Earp warns that countries, specifically like Cambodia, have also witnessed the internet being used to enhance smear campaigns and the spread fake news.

“[In Cambodia], supporters of both the ruling and the main opposition parties have been accused of sponsoring online support and smearing their opponents — although the long-ruling incumbents obviously have significantly more resources to suppress their opponents.”

Some major developments from the 2017 report found that the personal information of politicians were leaked, of both the ruling and opposition party, in these smear campaigns and two opposition politicians – including former opposition CNRP leader Sam Rainsy – were sentenced to prison for content that was shared on Facebook. Rainsy, who currently lives in self-imposed exile in France, was found guilty for a Facebook post that questioned the validity of the number of genuine ‘likes’ Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Facebook page had receieved. And opposition Senator Hong Sok Hour was sentenced to seven years for posting a ‘fake’ border treaty between Cambodia and Vietnam on Rainsy’s Facebook wall.

Various forms of intimidation and violence against journalists and activists online was seen to be in keeping with the country’s clampdown on independent media, the report found. Hacking was a widespread problem throughout the time period assessed, and the death of activist Kem Lay underscored this trend after he was murdered following the comments he made that criticised the government of corruption.

Myanmar: Grade: 63

The third country from Southeast Asia to be given the ‘not free’ grade was Myanmar; a ranking that Earp said was one of the greatest letdowns from the entire report.

“Internet freedom in Myanmar declined in the first year after the election of the NLD [National League for Democracy] – that was a big disappointment,” she said.

“The number of people arrested for online speech shot up, and the government urgently needs to reform the Telecommunication Law to stop it from being used as a tool to jail journalists and ordinary people who express their opinions on the internet.”

Contributing to their not free grade was an upshot in prosecuting people for online speech – at least 61 people have been prosecuted under the new administration – and five even ended with prison sentences of up to six months.

In addition to all of the traditional affronts that a country with a low-ranking internet freedom would posses, that is censorship, manipulation of the media and violation of rights, Myanmar also faces an uphill battle when it comes to confronting obstacles of accessing the internet.

Though they have seen extraordinary growth in recent years for internet penetration, they still rank among the world’s lowest. Part of the reason behind this is inadequate infrastructure, which is further compounded by a high rate of poverty.

But Earp warns that, just because a country is witnessing an increase in internet penetration, it does not mean they will be considered ‘freer’.

“Even countries like Cambodia and Myanmar, where internet penetration is seeing extraordinary growth, did not improve overall, essentially because as more people access information and communication technologies, more people are arrested and sentenced to prison for comments on social media.”

Thailand: Score: 67

Thailand, it was shown in the report, continues with its downward spiral, a trend that began in 2014 after the junta takeover. In 2013, they had actually achieved a grade of being ‘partly free’ (60), but have consistently been violating rights and increasing censorship since the death of King Bhumibol Adulyadej in October 2016.

“When we see restrictions play out in an actively repressive environment as part of an agenda to maintain power, the consequences are severe,” Earp said when commenting on the “tremendously troubling” developments in Thailand.

In one of these developments, politicians and government officials were encouraging citizens to report ‘unpatriotic content’. For instance, there was a senior police official who was publicly recruiting people to act as the ‘eyes and ears’ of the state and was awarding them with $15 for reporting their findings.

Freedom of access continued to be undermined, and at least three people have received prison sentences of more than a decade for their online activity.

But what Earp found to be one of the more paradoxical findings from the report on Thailand was a new legal amendment, which governments in the UK and Hungary have also proposed, that could see end-to-end encryption being undermined.

“It’s striking that some European governments who should be pushing back against the Thai authorities actually appear to be using the same playbook,” she commented.

Vietnam: Score: 76

Vietnam received the worst score out of all the Southeast Asian nations assessed, and possibly more concerning was that they came close to par with the much larger nations of China and Russia when it came to online censorship, both of whom have far more resources to dedicate to online content control.

In the time period that the report assessed Vietnam, there was an intensified crackdown on bloggers and critics of the government, seen most severely in the ten-year prison sentence that was handed down to ‘Mother Mushroom’, a blogger and activist, in June of this year.

Part of the reason why Vietnam is tightening up on measures against bloggers and social media activists is due to the strict rules that online editors, journalists and producers must adhere to when distributing their content online.

These rules for publishers, the report found, had not improved. All content must pass an in-house censorship test and then be submitted to a party committee who provides detailed instructions of what can and cannot be reported on.

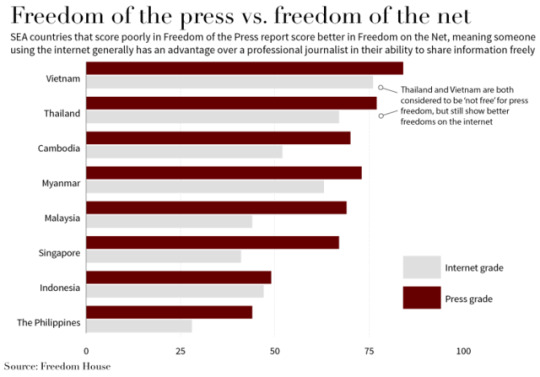

But despite its bleak outlook, Earp believes that the current climate for online journalists and bloggers in Vietnam is still better than those of traditional media outlets.

“Someone using the internet will still generally have an advantage over a professional journalist in terms of their ability to share information freely,” she said.

This favouring towards the internet, she remarked, was a trend seen across Southeast Asian countries who had alternatively scored rather poorly on the Freedom of the Press report.

A downward trend

In all, both the report and Earp did not reverberate a positive outlook for the path ahead, particularly where it concerns Southeast Asian countries that will be seeking to conduct elections in the next few months.

“Democracies and authoritarian regimes alike are introducing broad restrictions on internet freedom, ostensibly to protect citizens. And the message from Southeast Asia is that the scope for abuse is huge,” she said.

For things to improve, she says, the responsibility is initially going to fall on the individual. Where governments may fail to enforce standards, specifically as it relates to the spread of fake news and online manipulation, the person reading the news may have to exercise an extra level of caution on accepting what’s true and what’s false.

“The global community needs to be extremely vigilant about protecting internet freedom right now,” Earp warned. “Particularly in the face of content manipulation, terrorism, hate speech, and other trends that are leading governments to try and undermine encryption or limit free speech.”

You can read the full Freedom House Freedom of the Net report here. Madeline Earp is a senior research analyst with Freedom House and the editor of the Asia portfolio.

93 notes

·

View notes