#and the owner was a farmer whose livelihood depends on the animal

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

there was a buffalo that was about to die soon but we were not allowed to tell it to the owner

#and the owner was a farmer whose livelihood depends on the animal#he was so sweet#when you meet with people from village who've travelled long enough for their animals just to get treated#you can see the hope in their wet eyes#this buffalo alone must've cost 1.5 lakh#and the economic gain from is milk is far beyond to sustain livelihood of farmers and their families#but they don't accept that their everything won't survive anymore#and we saw those poor animals#bitch with a tumor she kept whimpering#and a chihuahua who was so weak and helpless we couldn't even collect enough blood for cbc#ive been to clinic few times before this but none of the cases were this bad#also there was this rich lady with her toy breed dog who barely didn't eat for like two days and she got done all the scans and tests done#in moments like this it truly hits the condition of farmers in our country#fucking pathetic#i know its so much easier to open a clinic in metro city for dogs and cats where pets from rich families would come and youncan just do your#little oohs and awws#and no one wants to touch a cow or buffalo or goat because they don't fit in your cute aesthetic animals of what makes you a vet#but i keep thinking about the eyes of those owners as well as their livestock

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOGTOBER 10/12/2021: LAMB/Dýrið (2021)

Yesterday was a difficult day of Blogtober, in which my choices were a seminal SOV feature that I didn't feel completely qualified to judge, and a movie that may not totally qualify as a horror movie. The latter film is LAMB—which, if you don't already know what it's all about, I strongly recommend you watch it in complete innocence, if that is still possible. What follows is a detailed discussion of the film, including its conclusion.

Valdimar Jóhannsson's dark Icelandic fable concerns a pair of childless farmers who get an unexpected, and unexplainable chance at happiness when one of their sheep gives birth to a half-human lamb. When María (Noomi Rapace) takes the creature into their home, Ingvar (Hilmir Snær Guðnason) balks at first, but is quickly charmed by the child they come to call Ada. The couple refuse to question this dubious blessing, to the point of María coolly shooting Ada's forlorn, meddlesome mother, and burying the animal in a shallow grave. When Ingvar's ne'er-do-well brother Pétur (Björn Hlynur Haraldsson)—himself a kind of satyr—shows up unannounced, his skepticism threatens to undo the new family, but it turns out that no one can help falling in love with Ada. The bestial Pétur's presence is still not altogether appropriate, but María and Ingvar manage to protect their marriage, and their form of parenthood, putting their commitment to one another ahead of weakness and temptation. However, noble intentions are no match for the inevitable, terrifying return of Ada's real father.

Though it is largely free of dialog, LAMB has a lot to say about our relationships with one another, and with animals. (After all, its Icelandic title, Dýrið, simply means "the animal") As far as humans are concerned, animals exist on a spectrum with livestock on one end, and pets on the other. María and Ingvar have sheep as their livelihood and sustenance, and their additional employees are a sheepherding dog and a patrolling house cat. Ada is accepted into the house as a pet is, privileged with an indoor existence and access to human food, in exchange for amusement and affection. The word "pet" may suggest a subordinate companion kept essentially for fun—considered to be more or less temporary, with their short lifespans—but for many pet owners, there is a full psychological engagement that borders on inappropriate, depending on your take. We are unfortunately capable of projecting human qualities and emotions onto creatures whose subjectivities we can't begin to understand, which is reflected in Ada's growing awareness that she does not resemble María and Ingvar, whose profession makes her increasingly uneasy. The differentiation we make between animal pests, animal products, and animal companions is purely artificial, usually only a matter of tradition. LAMB gets at this by having its actors actually midwife several lambs, leading up to the adoption of the one that is purely a special effect. María draws the line between the bipedal Ada and her four-legged mother with a bullet, which would make the blunt irony of the revenge of Ada's biological father almost comical, if it weren't so devastating.

Setting aside María and Ingvar's blindness to their own hypocrisy, LAMB is unusual in that the couple really tries their best to do what's right. So many dark independent dramas wallow in their characters' personal flaws, exalting all manner of emotional violence and selfishness as a part of the bittersweet beauty of human life. It can be tiresome, and somewhat insulting. LAMB offers its protagonists plenty of opportunity to screw up; certain past indiscretions and traumas are unforgotten, but they only serve as a motivation to get things right this time. This is just what makes the movie so agonizingly worrisome. Their happiness with Ada is excruciatingly fragile, always vulnerable to innocent accidents or the judgment of others, and this can be a much greater source of anxiety than the supernatural presence lingering at the edges of the film.

On that note, it's hard to say what genre LAMB fits into. I hesitate to call it a horror movie strictly because its chief aim is not to horrify; the sense of dread drops away in the family's most beautiful scenes together, screen violence is very limited, and the otherworldly imagery fits comfortably into the realm of fantasy. It's easier to call it folk horror because of its central conflict between modern men who strive to dominate nature, and a vengeful natural force that rejects cultivation and defies scientific understanding. Accepting that argument raises some interesting questions about what differentiates horror from folk horror; the latter is a taxonomic branch of the former, but they don't always serve the same purposes.

Which brings me to something I wanted to use this space to say, even if it is only tangentially related to what I'm saying about LAMB: I'm getting really sick of hearing people talk about movies being "genre fluid" or "genre adjacent" or, in one way or another, "not really a horror movie (even though it looks and acts like one)". I feel like these hair-splitting discussions are often not in good faith. For one thing, what are they meant to accomplish, if it is NOT catering to people who still look down on horror? How is our understanding of a film deepened by the insistence that it is "not really" horror? I genuinely don't know, and conversations around this topic always sound like a lot of insidious marketing language to me. And I don't usually hear this from the mouth of someone who doesn't think they made a horror movie at all, and is surprised and delighted to have found appreciation from the horror community; it's usually someone who is a self-described horror fan, who seems to have made a horror movie and submitted it where horror cinema is showcased...and then they kind of walk back on what the movie is once they're asked, as if the "horror" label is depriving them of something. It's one thing to say that a movie like LAMB incorporates some horror elements into what is chiefly a fantasy—and there do exist truly genre-bending movies, like THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW which has the audacity to do everything at once—but it's another thing to suggest that a film's dominant horror nature is diluted or subjugated by the inclusion of anything that isn't...well, whatever "pure horror" is presumed to be, which is rarely defined in these evasive analyses. I always suspect the speaker of trying to gain something by distancing themselves from the oft-maligned genre; I detect an implication that horror needs to be "elevated" by the introduction of non-native elements, as if horror itself cannot contain elements of drama, humor, and tragedy. (How does one even tell a story without one of those three things? Is "pure horror" supposed to be non-narrative?) One way I can tell there's a problem here is that we simply do not hear these arguments about other genres. You never hear someone nervously saying that their musical is "comedy-adjacent", or having coy, tricky debates about whether a drama is no longer a "real" drama once it incorporates one or two surreal elements. People throw around hyphenates like "romantic comedy" and "sci-fi/fantasy" all the time without couching them in a ponderous open-ended interrogation. Sometimes this is a matter of what I call "hot take syndrome", where people compete to say the least likely thing the most convincingly; I'm reminded of certain frustrating conversations I've had with people who think they're breaking new ground by claiming that LEON: THE PROFESSIONAL is "actually a romance, NOT an action movie," as if a relentless blood-drenched action movie ceases to be that, if it has a (dicey) relationship at its core. But I think in the case of horror specifically, there's something condescending and cowardly going on that people—especially fans and professionals who purport to love horror—just don't want to admit to openly. It's apologism, and it stinks.

#Sjón#Valdimar Jóhannsson#Hilmir Snær Guðnason#Björn Hlynur Haraldsson#noomi rapace#supernatural#horror#folk horror#fantasy#lamb#2021#Dýrið

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

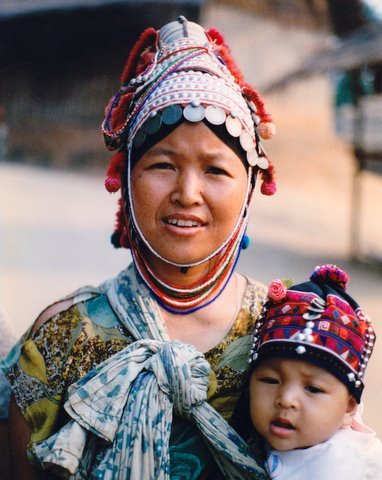

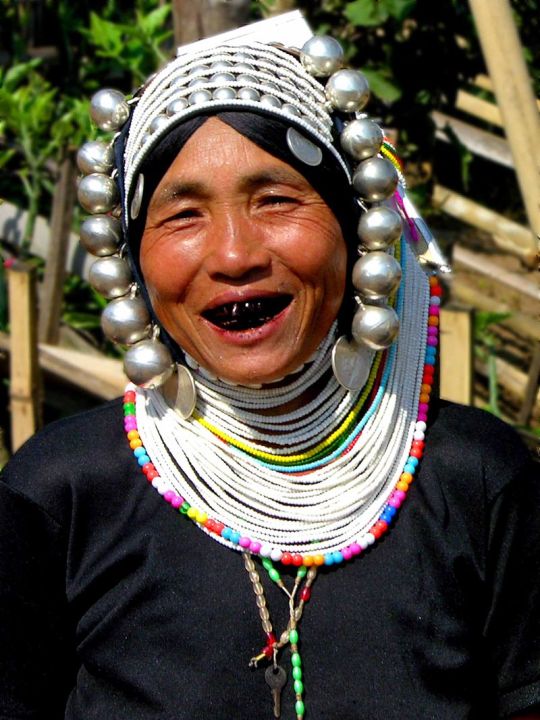

1. Akha hilltribe girl, Chiang Mai flower festival, Thailand by Steve Vidler 2. Pamee Akha woman with traditional headdress with silver coins, Thailand by Jim Goodman 3. Akha woman of Laos 4. Tachilek Akha 5. Akha girl in Laos 6. Akha woman and child, Thailand 7. That Xieng Tung Festival, Muang Sing, Laos. Akha young girls in the welcoming committee. On their arrival, visitors will have a color ribbon pinned to their blouse in exchange for a donation.

The Akha are an indigenous hill tribe who live in small villages at higher elevations in the mountains of Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Yunnan Province in China. They made their way from China into Southeast Asia during the early 20th century. Civil war in Burma and Laos resulted in an increased flow of Akha immigrants and there are now some 80,000 living in Thailand's northern provinces of Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai, where they constitute one of the largest of the hill tribes. Many of their villages can be visited by tourists on trekking tours from either of these cities.

Due to rapid social and economic changes in the regions the Akha inhabit, particularly the introduction of Western modes of capitalism, attempts to continue many of the traditional aspects of Akha life are increasingly difficult. Despite these challenges, Akha people practice many elements of their traditional culture with much success.

The Akha people are often noted for their very recognizable sartorial practices. Akha women spin cotton into thread with a hand spindle and weave it on a foot-treadle loom. The cloth is hand dyed with indigo. Women wear broad leggings, a short black skirt with a white beaded sporran, a loose fitting black jacket with heavily embroidered cuffs and lapels. Akha women are known for their embroidery skills. While traditional clothes are typically worn for special ceremonies, one is more likely to see Akha villagers in full traditional garb in areas that have heavy volumes of tourists, particularly in Thailand.

The headdresses worn by the women are perhaps the most spectacular and elaborate items of Akha dress. Akha women define their age or marital status with the style of headdress worn. At roughly age 12, the Akha female exchanges her child's cap for that of a girl. A few years later she will begin to don the jejaw, the beaded sash that hangs down the front of her skirt and keeps it from flying up in the breeze. During mid-adolescence she will start wearing the adult woman's headdress. Headdresses are decorated by their owner and each is unique. Silver coins, monkey fur, and dyed chicken feathers are just a few of the things that might decorate the headdress. The headdresses differ by subgroup.

According to an article about the variations in Akha headdress, "High Fashion, Hill Style", the

"Ulo Akha headdress consists of a bamboo cone, covered in beads, silver studs and seeds, edged in coins (silver rupees for the rich, baht for the poor) topped by several dangling chicken feather tassels and maybe a woolen pom-pom. The Pamee Akha wear a trapezoidal colt cap covered in silver studs with coins on the beaded side flaps and long chains of linked silver rings hanging down each side. The Lomi Akha wear a round cap covered in silver studs and framed by silver balls, coins and pendants and the married women attach a trapezoidal inscribed plate at the back."

^Myanmar (Her teeth have been intentionally dyed black, a relatively common practice in parts of east and southeast Asia. The lacquer used prevents tooth decay.)

^Laos

^Laos

^Thailand

^Thailand

^ Ban Mae Chan Tai, Chiang Rai Province, Thailand

Akha society lacks a strict system of social class and is considered egalitarian. Respect is typically accorded with age and experience. Ties of patrilineal kinship and marriage alliance bind the Akha within and between communities. Village structures may vary widely from the strictly traditional to Westernized, depending on their proximity to modern towns. Like many of the hill tribes, the Akha build their villages at higher elevations in the mountains.

Akha dwellings are traditionally constructed of logs, bamboo, and thatch and are of two types: "low houses", built on the ground, and "high houses", built on stilts. The semi-nomadic Akha, at least those who have not been moved to permanent village sites, typically do not build their houses as permanent residences and will often move their villages. Some say that this gives the dwellings a deceptively fragile and flimsy appearance, although they are quite well-built as proved over generations.

Entrances to all Akha villages are fitted with a wooden gate adorned with elaborate carvings on both sides depicting imagery of men and women. It is known as a "spirit gate". It marks the division between the inside of the village, the domain of man and domesticated animals, and the outside, the realm of spirits and wildlife. The gates function to ward off evil spirits and to entice favorable ones. Carvings can be seen on the roofs of the villager's houses as a second measure to control the flow of spirits.

The traditional form of subsistence for the Akha people has been, and remains, agriculture. The Akha grow a variety of crops including soybeans and vegetables. Rice is the most significant crop and is prominent in much of Akha culture and ritual. Most Akha plant dry-land rice, which depends solely on rainfall for moisture, but in some villages irrigation has been built to water paddy fields. Historically, some Akha villages cultivated opium, but production diminished after the Thai government banned its cultivation.

The Akha have traditionally employed slash and burn agriculture, in which new fields are cleared by burning or cutting down forests and woodlands. In such a system, there is usually no market for land. Rights to land are considered traditional and established over many generations. This type of agriculture has contributed to the Akha's semi-nomadic status as villages move to clear new farmland with each successive burn cycle. The Thai government has forbidden this practice, citing its detrimental effects on the environment. The Akha have adapted to new types of subsistence farming, but the quality of their land has suffered as they are no longer allowed to expand onto new plots. In many cases, chemical fertilizers are the only option for re-fertilizing the land.

Akha religion — zahv — is often described as a mixture of animism and ancestor worship that emphasizes the Akha connection with the land and their place in the natural world and cycles. Although Akha beliefs and rituals involve all of these elements, the Akha often reject the casual categorization of their practices as such saying it simplifies and reduces its meaning. The Akha way emphasizes rituals in everyday life and stresses strong family ties. Akha ethnicity is closely tied to the Akha religion. It might be said that to be considered an Akha ethnically by other Akhas is to practice the Akha religion.

The Akha put a heavy emphasis on genealogy. An important tradition involves the recounting by Akha males of their patrilineal genealogy. During the most important ceremonies the list is recited in its entirety back over 50 generations to the first Akha, Sm Mi O. It is said that all Akha males should be able to do so. The recounting of this lineage plays a role in the incest taboo: If a male and female Akha find a common male ancestor within their last six generations, they are not allowed to marry.

Rights, issues, and activism

Being an ethnic minority with little easily accessible legal recourse, Akha everywhere have long been subject to rights abuses.

Perhaps the most important issue facing the Akha pertains to their land. The Akha relationship to land is vitally connected to the continuation of the Akha culture, but they rarely have "official" or state-sanctioned land rights or claims to their land as land rights are considered traditional. These conceptions of land are at odds with those held by the nation states whose land the Akha now occupy. Most Akha are not full-fledged citizens of the country they inhabit and are thus not allowed to legally purchase land, although most Akha villagers are too poor to even consider purchasing land.

It has been reported by rights groups that several land seizures of Akha land have been undertaken in the name of the Queen of Thailand. Originally a semi-nomadic people, the Akha are often relocated by the presiding national government to permanent villages, after which the government allegedly sells to logging companies and other private corporations access to lands formerly occupied by the Akha. The land onto which the Akha are displaced is almost always less fertile than their previous plots. On their new lands, the Akha can rarely produce enough food to sustain themselves and are often forced to leave and seek employment outside the villages, thus disrupting their traditional culture and economy.

In Thailand, laws have been passed that curb people's rights to the forest, including the 2007 Community Forest Act. According to the network of indigenous peoples in Thailand,

"These laws and resolutions have had severe impacts on indigenous peoples' rights to residence and land. Under these laws and resolutions millions of hectares of land have been declared as reserved and conservation forests, or protected areas. Today, 28.78% of Thailand is categorized as protected areas. As a result, thousands of farmers previously living in the forest or relying on the forest for their livelihood have been arrested and imprisoned and their lands seized. Cases have been filed against them for the so-called encroachment on government land."

Despite having signed and ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Thai government has not changed laws to adhere to those recommendations emphasizing respect for the rights of indigenous peoples and their full and effective participation in protected areas management and policy-making.

The reasons given for Akha relocations vary, but a common response on the part of the Thai government is to cite a concern for the preservation of forests and the promotion of more sustainable agricultural techniques than the slash and burn agriculture traditionally used by the Akha.

Despite their numbers, the Akha are the poorest of all the hill tribes. As roads bring accessibility and tourists, they provide relief from the poverty of village life, especially for the younger generations who increasingly find themselves engaged in labor outside the villages. Many villages report a population decrease as many leave to find work in the cities, often for very long periods. Many Akha complain that the younger generations are becoming increasingly less interested in traditional culture and ways and more and more susceptible to outside, mainstream, cultural influences. According to one author, where the village squares were once "filled with the sounds of courtship songs", radios are now more likely to play pop hits.

As it becomes increasingly difficult to remain self-sufficient through agriculture, and as roads open up the villages to the cities, the Akha must contend with the sometimes corrosive effects of the tourist industry. Not all Akha are happy to let tourists come in and observe village life.

Many Akha complain of the missionaries that come to the villages to convert them, sometimes forcibly, to Christianity. Many Akha feel that the missionaries generalize about, or in this particular case, "paganize" the Akha traditional belief system, demeaning their longstanding beliefs. Some of the claims made against missionaries include the kidnapping of Akha children into orphanages and forced labor, the sterilization of Akha women and the forced or underpaid labor of Akha on farms. Many rights groups make the claim that the money spent by missionaries on building churches and furthering Christian education could be better spent on helping the Akha with medical and sanitation improvements that are greatly needed in most villages.

264 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What we have lost

Apparently the least interesting of all the topics I bring up, is the topic of rewilding, because my rewilding posts typically only get 1-3 notes, when I present you with amazing videos or other material.

And I think that is an outrage, because in my opinion, this is the most important topic anyone could talk about. Of every topic in the world, in politics, social problems and topics of the natural world, if I had to choose one, rewilding would be my number #1 topic to talk about.

Yet almost nobody is talking about it, or has even heard about it.

So prepare to be bored some more, because I’m not done talking. Although my post about diminishing habitats of present-day animals, many of whom we think of as "African" (while they actually belong over most of Eurasia, and some even in North America) got pretty popular, I want to focus more specifically on the destroyed state of Europe today.

We can whine, yell and complain until our faces turn blue about the destruction of Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Amazon. And we wouldn't be wrong, as China-India-Indonesia and everything inbetween is the most heavily populated place on Earth currently, and Africa is going to become the next one.

“Only” a little over a billion people in Africa today, but if current population trends continue for 82 years, until 2100 (they won't, because numbers always change and this number is impossible to reach without a massive change in how we make and distribute food, but for the sake of argument), the human population in Africa will reach 15.5 billion people by the turn of the century. That's more than twice the entire worldwide population today, crammed into in Africa alone.

African animals are already in a dire state, there is hardly any wildlife left in west Africa, or really anywhere outside of reserves. Not to mention the huge human rights and welfare problems on the continent, but this is how bad the population explosion is right now.

And then there is South America. The northern part, the Amazon, to be precise. We hear all the time how much of the Amazon has been destroyed, mainly in order to graze cattle that we eat in Europe and North America.

But when do we ever talk about environmental destruction in Europe? We don't, because we're used to it. In the other three continents I talk about, we are seeing things change drastically within a single human lifetime. And it's really important and great that people are talking so much about it.

But we are not talking at all about the destroyed state of Europe, simply because it's been this way for centuries and we think this is "normal". We think Europe is the only place on Earth that's "boring", not "wild". It never was, it was always just houses, farms and few wild animals tougher than a fox or bigger than a roe deer.

But it has not at all always been like this.

And this is where my main gripe with the current discussion comes in. Because most of us love to bash on people in these other continents. Poor, uneducated farmers (really, I can't understate the difference in their kind of life to yours or mine, or their education level and understanding of the natural world compared to yours or mine, because they were simply born with different opportunities), whose very livelihood depends on their hard, manual, thankless jobs, and they simply can't care about some elephants destroying their crops, or some tigers or lions killing and eating their livestock.

As disturbing as this recent photo of a young elephant being set on fire was, and how evil this seems to me and you, it does no good for the elephants or the other animals there to meet the people as a whole with hate, or say things like "they are devils with no heart or feeling for their fellow creatures", or "may they burn like they burned this poor elephant".

These are not direct quotes, but approximations of what I see every time these human-animal conflicts come up.

These people's opportunities in life are so different from yours and mine, that they simply have never been able to see an elephant, a tiger, a lion, a rhinoceros, the way you and I see these animals.

It's easy for us to sit in our golden towers (and even if you live in a shitty studio apartment, it is a golden tower compared to their existence, and you'll never have to worry about your children starving to death) and talk about kind and majestic, intelligent and feeling animals.

They see a wild beast who's threatening their very lives. And none of that is going to change by hating on them and telling them they're worthless pieces of shit. It can only change by educating them about the animals, and minimizing the risk for human-animal conflict.

Why all this then, what does this have to do with Europe? Because we're such horrible hypocrites. We sit in our (comparatively) golden towers, in our (comparatively) comfortable existence, and judge these people, when our own home has been destroyed and practically empty of wildlife for centuries.

This is the state of wilderness in Europe. And as a Swede, I'll let you know that most of our forest (the light green) is planted woods, not ancient, actual intact forest. And while people from continental Europe or Britain look dreamily at Sweden, Norway and Finland's vast wildernesses, we up here are terrible at taking care of our predators, as I have brought up many times, but lately have found it too heartbraking to keep up with.

We shoot bears and wolves "for protection" practically as soon as they're spotted. Young bear just left his mother, and is grabbing some apples? Shoot it. Mama bear just woke up from hibernation and tries to feed her three hungry cubs by killing a reindeer calf? Shoot her, and her cubs too.

And the reindeer industry is nowhere near the "cultural heritage" it is called. Back in the day, one man had maybe a hundred reindeer he herded with dogs, and on foot. Now they own ten thousand reindeer in a single herd, they herd them with helicopters and snowmobiles, and transport them to slaughter in massive trucks. Cultural heritage my ass. And if a genetically important wolf from Russia kills 5 out of these 10 000 reindeer over the course of several months, it has to be shot NOW, despite massive taxpayer money for every single predator-killed reindeer, and for the reindeer owners to simply have wolves on the land. Our peninsula is a disgusting outrage (Finland too, these three countries are all terrible at valuing their natural predators).

*End rant*

It is funny how this map considers Scotland "intact wilderness", since it is a completely ruined landscape filled with nothing but sheep, deer, and grass, as I have brought up multiple times before (the rewilding tag).

About the British Isles.

The wolf is believed to have become extinct in England as far back as the reign of Henry VII (~1500), and the last confirmed wolf in Scotland was killed in 1680.

The last wolf in Ireland was shot in 1786, the century when rich landlords all over western Europe were intentionally propagandizing people to fear wolves. You see, the landlords wanted wolves off their land, so they could have all the deer to themselves. But the poor farmers had much better things to do with their time than to chase after wolves, so they couldn't be bothered.

Thus the landlords conjured up this image of the blood-thirsty, man-eating wolf, the Devil's pet, the one who must be exterminated at all costs. And from there, we have a three hundred year history of wolf hate which has lasted in western culture to this day (and which European emigrants brought with them to America).

Modern-day anti-wolf propaganda in the United States.

The United Kingdom today, Great Britain to be specific, is a truly mind-boggling country, so outrageous that I can barely put it into words. They actually pay people (with taxpayer money of course), to destroy their land so that nothing can grow on it. And in Scotland specifically, they call this destroyed landscape "come see wild Scotland, please give us your tourist money!" You can hear all about the outrageous state of this island here.

In other places, like in South America, Africa and Southeast Asia, we shout and yell and do everything to defend the rainforest against the ranchers. In Britain, we defend the ranchers against the rainforest and call it “conservation”.

The map above shows the range of the grey wolf in Europe today. It has a strong population in eastern Europe, where it is, incidentally, not hated irrationally like in the west, and also in northern Spain where there are roughly 2000 wolves (to compare, Norway has about 50, Sweden 300, and Finland 100-300). It's not like eastern europeans are huge wolf-huggers or nature lovers, but they don't have the old cultural hatred of wolves that westerners have been instilled with.

Brown bears have a strong population in northern Europe of several thousand, but are otherwise restricted to distant mountain ranges, like the Pyrenees and Alps.

Eurasian lynxes have likewise been extirpated (been made regionally extinct) in almost all of Europe, except again for Scandinavia, the Baltic countries, and a few remote pockets in continental Europe. Despite the fact that this is a relatively small, very shy and completely harmless cat that hardly ever takes livestock due to their fear of humans, and prefers to live off of hares and small deer, there seems to be no room for them in modern Europe.

Not to mention the smaller, unique Iberian lynx species, which lived only in Spain and Portugal and is today all but extinct.

Those are just the largest predators. Then there is the Wisent, or as I prefer to call them in order to give people some emotion when they hear the name, the European Bison.

This megafauna of Europe once stretched from northern Spain to southern Sweden and Finland, all the way to Lake Baikal and northern Mongolia.

In the middle ages, they were restricted to central-eastern Europe. Today there are only a few thousand left, most in captivity or reserves, though the map is not completely accurate, as today they have been reintroduced in small numbers in Poland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Russia and strangely enough, in Kyrgyzstan.

Meanwhile, we have invasive musk ox in Norway and Sweden that are protected, but nevermind that. Invasive species are protected, while our native megafauna is extirpated, and our "protected" predators are massacred.

And the Aurochs, the wild form of our domestic cattle, once ranged across all of this. Then they were domesticated, the remaining wild animals were in the way of the domestic stock (as in Africa today), and the last Aurochs died in 1627.

Projects exist to try to breed it back from domestic cattle, but that's kind of like trying to breed a replica wolf from domestic dogs, or quaggas from zebras. The animal is still gone (but the replacement could fill the same ecological niche, unless you're a complete conservation purist, which I'm definitely not).

That's our top predators, and our most recent megafauna. I definitely don't think it's too much to ask to bring these back, in my lifetime even.

That is what rewilding is. Not just the dramatic introductions of large animals of course, there's also the lot less sexy topics of planting trees and reintroducing ecosystem engineers like beavers, but these large animals are the best advertisement for rewilding. A healthy ecosystem with them back as the kings and queens of their former domains is the goal.

There also used to be lions, cheetahs, hyenas, rhinos, hippos and straight-tusked elephants all the way to Great Britain, but that is probably too extreme even for rewilding projects in this century. That is why I added that picture of the lions by the way. Those are African lions in a zoo, but even they grow thick winter coats when put in a cold climate, and they once roamed all over Europe.

And this is why I can only shake my head when people hate on said poor, uneducated people in Africa and Asia (less sympathy from rich cattle ranchers in South America from me, it's not poor natives cutting down rainforests or killing Jaguars there, it's an entirely different situation).

Because if you are a sheep farmer or reindeer herder in Scandinavia, you can change your job. Easily (again, comparatively). You and your family will not have to go hungry one day in their lives. You are educated. You know about these animals. You know about how ecosystems work. You have resources. Yet, as a collective, we do this.

Conservation is about trying to preserve what's here today. Rewilding is about ecosystem restoration, to revive what we have already killed.

Destruction in Borneo.

Destruction in in the Amazon.

A destroyed, empty landscape being celebrated as "wild" and "natural", in Scotland.

Destruction in Madagascar.

Taxpayer funded "conservation" in England.

Taking care of protected species and ensuring their genetic diversity, in Sweden.

That is why we should be much more outraged about Europe.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Managing an estate

by Maria Grace

There were two major types of great landowners in the regency era–the aristocrats who were deeply involved in running the government, but rather less hands-on in regards to their estates, and land-owning gentry, who were very hands-on and represented the majority of land owners. A country estate was a complex economic mini-state that typically included a residence of sufficient size to suit a gentleman with parkland, gardens, stables and paddocks. A large agrarian business extended out from this center, consisting of a home farm and gardens, numerous tenanted farms and cottages usually in a village near the manor. The survival of the resident family, household staff, tenant farmers and their families and workers depended on revenues from the estate's agricultural enterprises and rents. (Laudermilk, 1989) A successful estate owner needed solid business acumen. But why? Gentlemen did not work for their income, did they? Technically, they did not. Their income came largely from rents and investments. Estates often had small villages within their boundaries including church and parsonage, stone, brick or timbered farmhouses, and cottages, even wind/water mills in a few narrow lanes, all surrounded by productive (and often leased out) meadows and fields. (It was generally considered a village, not a town because it had no market, the defining characteristic of a small town.) Estate owners might also receive revenue from the sale of products from their land, including crops, animal products, timber and minerals.

Rent

Estate owners leased out various kinds of property, including tenant farms of various sizes, houses and cottages, and even small estates that might be part of their holdings. Rents rose dramatically between 1790 and 1830, in some cases increasing fivefold over that period, making rents a considerable source of income, especially for large estate owners. (Murray, 1998) Since a gentleman did not dirty his hands with money, for him to collect the rents from this himself would have been vulgar. A steward, or in the case off smaller estates, a bailiff, would be hired for that task and others related to estate management.

Stewards and Bailiffs

Whereas a bailiff might be an estate's major tenant hired to simply collect rents, a steward was an educated man, often the son of clergy, a smaller landowner or a professional man, hired to assist in the running and management of the estate. A steward was not considered a servant, but rather a skilled professional. For this reason, he was addressed as 'Mister'. Not long after the regency era, the term 'steward', having servile connotations, was dropped in favor of the more professional term 'land agent.' Stewards frequently had experience and training as solicitors which was particularly useful in their duties managing contracts and overseeing estate accounts. Beyond these duties, stewards also collected rents, leased land, supervised the tenantry, directed any work done on the land, settled squabbles that arose among the tenants or workers, purchased animals, seed and so on. (Shapard,2003) The steward would often have a home of his own, but would on occasion stay at the manor. His duties might regularly take him to the family's other country houses, and to London, but he was unlikely to travel with the family on a regular basis. (Martin, 2004)

Farming

Tenant farmers

By 1790, three quarters of England's agricultural land was cultivated by tenants. (Day, 2006) The remaining quarter represented small yeoman farmers whose numbers would decrease through the ensuing century. Tenants usually rented sections of land with farmhouse and outbuildings, paid their rents on the established quarter days: Lady Day (March 25), Midsummer (June 24), Michaelmas (September 29), Christmas (December 25), sold the produce, and kept the earnings. Customary provisions required the landlord to supply materials, buildings and facilities such as drainage and hedging while the tenant provided stock, seed and tools. (Davidoff, 2002) Farmers, including tenant farmers, made up the middling ranks of rural society. They could become quite well off with their sons and daughters educated as they moved up the social scale. Though the sons of tenants could not inherit the land their father's works, they could inherit their farm leases. These leases, which traditionally ran for multiples of seven years, were often passed from father to son, with the land owners preferring to maintain the continuity of a known tenants and the relationships that went with it. (Davidoff, 2002) It was not uncommon for a tenant farmer to rent extra land with additional farmhouses for adult sons to farm. The eldest son would eventually take over his father's tenant farm when he retired or died. Widows might head a farm household, hiring help with the farm as needed until a young son was old enough to take over the tenancy. (Davidoff, 2002) Tenants normally looked to their landlord for assistance whether for personal matters or for help in improvements to the land. Some of these improvements might include better ways to farm the land and improve productivity.

Farming methods

With populations rapidly increasing, the best landowners sought out advanced methods of agricultural science to improve production (and profits.) The agricultural reports of the newly formed Board of Agriculture were avidly studied to learn more about advancements including crop rotation, scientific stock breeding, and new technologies including the seed drill and machines for threshing and chaff cutting. The installation of drainage in fields was another innovation practiced by many farmers during this era. Heavy clay soils where excess water made plowing more difficult and hurt the growth and root structure of plants would have rows of drains cut beneath the surface to move water away from the fields. (Shapard, 2012) Four-course crop rotation, commonly called the Norfolk four-course system, increased fodder production. There were many variations of this system, depending on the region. Typically, fields would be sown with wheat in the first year, turnips in the second, followed by barley in the third. The clover and ryegrass were grazed or cut for feed in the fourth year. This produced two cash crops and two animal feed crops. One constant was the presence of livestock as part of the strategy. Sheep (or sometimes cattle) were turned out to graze the turnip tops. This kept weeds down and allowed the field to be fertilized by mobile manure factories. Turnip roots were stored for winter animal fodder. More fodder meant larger livestock herds and the ability to keep animals through the winter. Improvements like these could double one's income. (Laudermilk,1989) In addition to increased agricultural production, estates began to enjoy profits from heretofore unexplored avenues such as mining and timber sales. Changes in technologies often fueled demand while improvements in transportation with new canals and steam engines made previously prohibitive production profitable.

Incomes

What kind of income could a landed estate provide? Naturally the answer depended a great deal on the size of the estate and the kind of management it had. For a little perspective, the 1801 census found that the average income of the 287 peerage families (all of whom would have landed estates) was approximately £8,000 The top 2000 merchant families averaged £2,500, whereas the top 6000 esquires that Austen's Mr. Bennet would have belonged to averaged £1,500. That suggests that the £2,000 a year Mr. Bennet had represents a very good income, compared to his peers.

To have an income above the average nobility as a gentleman estate holder, one did not spend a very great deal of time sitting about enjoying the social life of the town. While a man like Austen's Mr. Darcy might take time to enjoy the finer things as it were, he would also have to spend a very great deal of time and effort in managing the massive agricultural enterprise that provided those finer things. Technically a gentleman did not 'work' for his income. But planning how to keep an estate afloat through the long years of the French war, determining how best to manage the home farm and advise his tenants considering the price of corn, debating whether to invest in draining a new field or if rain will spoil the harvest or damage tenant houses that he will have to repair—and how to effect those repairs—seeking new hands to man the sawmill and cider press and what to pay them—all of that sounds a very great deal like what we today would call work. While there were inevitably bad landowners who put little into managing their estates, many, if not most put in a great deal of very hard work to manage estates that provided "livelihood and the stability for both the landowner and a vast army of workers–tenant farmers, gardeners, cowmen, sawyers and shepherds alike.(As well as providing employment for seasonal labourers like codders, harvesters, shearers…)" (Bennetts, 2012)

References

Adkins, Roy, and Lesley Adkins. Jane Austen's England. Viking, 2013. Austen, Jane, and David M. Shapard. The Annotated Pride and Prejudice. New York: Anchor Books, 2003. Austen, Jane, and David M. Shapard. The Annotated Sense and Sensibility. New York: Anchor Books, 2011. Austen, Jane, and Edward Copeland. The Cambridge Edition of Sense and Sensibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Bennetts, M.M., "At the heart of a great estate is… ." M.M.Bennetts. April 11,2012. Accessed May 20, 2014. http://mmbennetts.wordpress.com/2012/04/11/at-the-heart-of-a-great-estate-is/ Collins, Irene. Jane Austen and the Clergy. London: Hambledon and London, 2001. Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. Family fortunes: men and women of the English middle class, 1780-1850. London: Routledge, 2002. Day, Malcom. Voices from the World of Jane Austen. David and Charles, 2006. Ellis, Markman "Trade." In Jane Austen in Context , 269-77. Cambridge: University Press, 2005. Girouard, Mark. Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978. Gornall, J.F.G. "Marriage and Property in Jane Austen's Novels." History Today 17, no. 12 (December 1967). Accessed May 22, 2017. http://www.historytoday.com/jfg-gornall/marriage-and-property-jane-austen%E2%80%99s-novels. Hitchcock, Tim, Sharon Howard and Robert Shoemaker, " Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor Account Books ", London Lives, 1690-1800 (www.londonlives.org, version, 1.1 17 June 2012). https://www.londonlives.org/static/AC.jsp Laudermilk, Sharon H., and Teresa L. Hamlin. The Regency Companion. New York: Garland, 1989. LeFaye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels. New York: Abrams, 2002. Martin, Joanna. Wives and Daughters: Women and Children in the Georgian Country House. London: Hambledon and London, 2004. Morris, Diane H. "Mr. Darcy was a Second-Class Citizen." Moorgate Books. August 10th, 2014. Accessed May 22, 2017. http://www.moorgatebooks.com/10/a-true-regency-gentleman-had-good-breeding/. Ray, Joan Klingel. Jane Austen for Dummies. Chichester: John Wiley, 2006. Selwyn, David. Jane Austen and Leisure. London: Hambledon Press, 1999. Seven Trees Farm, "Norfolk four course." Seven Trees Farm. April 30, 2012. Accessed May 29, 2017. http://seventreesfarm.wordpress.com/2012/04/30/norfolk-four-course/ Sullivan, Margaret C., and Kathryn Rathke. The Jane Austen Handbook: Proper Life Skills from Regency England. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books, 2007. Swift, Deborah. "Law & Order - Duties of the Constable in 17th Century England." English Historical Fiction Authors. May 24, 2017. Accessed May 29, 2017. http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2017/05/law-order-duties-of-constable-in-17th.html Trevelyan, George Macaulay. Illustrated English Social History. New York: D. McKay, 1949. Vickery, Amanda. The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998. Watkins, Susan. Jane Austen's Town and Country Style. New York: Rizzoli, 1990. Wilson, Ben. The Making of Victorian Values: Decency and Dissent in Britain, 1789-1837. New York: Penguin Press, 2007.

~~~~~~~~~~

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was ten years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful.

After penning five file-drawer novels in high school, she took a break from writing to pursue college and earn her doctorate. After 16 years of university teaching, she returned to her first love, fiction writing. Click here to find her books on Amazon. For more on her writing and other Random Bits of Fascination, visit her website. You can also like her on Facebook, or follow on Twitter.

Hat Tip To: English Historical Fiction Authors

0 notes

Text

Author and conservationist Kuki Gallmann shot in Kenya

UK News

Author and conservationist Kuki Gallmann shot in Kenya

The Italian-born author and conservationist Kuki Gallmann was shot at her Kenyan ranch and airlifted for treatment after herders invaded in search of pasture to save their animals from drought, officials said Sunday.Gallmann, known for her bestselling book "I Dreamed of Africa," which became a movie by the same name starring Kim Basinger, was patrolling the ranch in Laikipia when she was shot in the stomach, local police chief Ezekiel Chepkowny said.The 73-year-old Gallmann had been with rangers from the Kenya Wildlife Service, assessing damage done to her property Saturday by arsonists who burned down buildings at one of Laikipia Nature Conservancy's tourism lodges, said Laikipia Farmers Association chairman Martin Evans.After the attack, the rangers transported her to a location where she could be airlifted to Nanyuki town, Evans said.

Lodges belonging to Gallmann were burned by the herders last month.This East African nation is facing a drought that has affected half the country and has been declared a national disaster.Herders, whose livelihoods depend on their cattle, and large-scale farmers in parts of Kenya's Rift Valley have been desperately waiting for seasonal rains that were to start last month to ease the drought and conflicts over grazing land in which more than 30 people have died.Kenya's military and police have been working to disarm and drive the hundreds of herders and their animals out of ranches they've invaded, but their actions appear to have escalated the violence.

Evans said.The land invasions started last year. British national and ranch owner Tristan Voorspuy was killed last month when he went to inspect damage done by the herders on one of his lodges.Opposition leader and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga said ranch owners deserve protection under the law like all Kenyans.

Prime Minister Raila Odinga

0 notes