#and she learns absolutely nothing and is thus a terrible protagonist in general

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I see so many stupid takes on what a “revised” ST storyline would look like. Granted, almost all of these are still better than the dumpster fire that is TROS. But a lot of these still don’t make sense because a lot of people still miss what I think you articulate so well in many of your metas: that the ST is about the Skywalker family, the unresolved trauma, and with Ben Solo as the heir and person who should tie up all the loose ends (I can’t put it as elegantly as you do, but the whole thing you have repeatedly said about him living and having children, reconciliation of Anakin and the Skywalker “name” to society, repairing the unresolved issues Leia had with her father, etc etc). I just saw another stupid take where Rey is Obi Wan’s secret daughter who has been abandoned (wow way to go shitting on Obi Wan’s character) and therefore has anger issues, hates the Jedi and worships Vader, Ben is not force sensitive and grows up a diplomat learning from Leia, Finn is a Jedi randomly, Poe is a pilot for no reason I can think of or why he even exists, and Rey needs to be saved by Ben (how? Why? Why not by Finn if Finn is the Jedi and Ben is doing just fine in life.) Oh and the dyad is created by Obi and Anakin’s ghosts, and also Rey is asexual bc she is too angry—I support asexual character representation but not if it is a manifestation of maladaptive behaviors rather than a healthy state of being). I mean, all of that could be interesting, maybe in an Obi Wan family saga spinoff series, but I fail to see how this is about the Skywalkers or ties in thematically to the central characters of OT/PT. Like why should we care? I suppose if we learned that Leia did reconcile with her father, and the galaxy at large knew of Anakin’s redemption, and Ben didn’t grow up with this fear of fatalism, fine I can see perhaps that storyline “working” but again...it wouldn’t really be about the Skywalkers anymore, who in that version seem to all be well adjustsd, happy fufilled functional people. But why not then just call that story a complete new series instead of a sequel...(and btw that “version” has almost no mention of Luke, and most OG fans are interested in seeing where their original heros ended up etc etc). I fail to see why Rey even needs to be around in these “alternate” versions. Just make a completely new story set in SW world but not a “sequel” then, that would be fine. Anyway, every time I see stuff like this, I come to your blog to re-read your metas because you are one of the very few people who GETS the story. Please preach some more to the choir (if inspiration strikes). I need to be reminded that there actual people in the fandom who cares about Ben, the Skywalkers, thematic coherence, and GOOD STORYTELLLING. Anyway thank you so much for your detailed and insightful analyses. They are truly a delight and a balm. If it’s not too much trouble, could you by chance link to some of your own fave metas you’ve written, or that you think are the most important to understanding the ST and Ben etc? Do you recommend any other bloggers whose metas on Ben and ST you feel are good and enjoy? Thank you!

Thank-you so much, anon! 🥰

Yes, the problem with so many ‘fix-it’ ideas or ideas of what the ST ‘should’ have been is that they have nothing to do with the Skywalker Saga or its themes. If you just want to write about new characters in the GFFA and not meaningfully continue the same narrative about the family and the question the Skywalkers exist to ask, then it’s not part of the same story. Which is fine, but it’s not a sequel. You can’t unpick the end of RotJ and destroy the resolution of the original character arcs if you’re then going to make them glorified cameos to give your unrelated newbies a pep talk without providing a fuller and more complete statement of the original message and the original arcs. That’s an either/or choice. Either actually make a sequel and deal with the implications of that or don’t.

The most stark contrast between TLJ and TFA/TROS is that TLJ is written as a fully equal and living part of the story, it treats the characters as characters and takes for granted that it is part of the saga not just a tribute to it. There are elements that are meta, it does comment, but it doesn’t approach the OT heroes as icons frozen in amber incapable of change or allow its new characters to act like fans of the films rather than people who live in the universe. And this is why it’s so much better and so much more memorable. It’s an actual story which stands on its own two feet.

Probably my most key posts on SW’s themes and worldview are in the tags space crime and punishment and the legacy. My Ben tag covers a lot those two miss and also has reblogs from other people whose meta I would really recommend (especially benperorsolo). This is a round up I did mostly about Rey’s arc/place in the story, but it’s pre-tros and missing some links. Her tag has more on sw protagonists and why I think none of the ‘alternatives’ people offer for Rey Nobody and Reylo work.

I think I linked most of my individual favourite posts in this answer lol.

#I got whelmed trying to choose posts to link#I always feel like i'm leaving out essential things#and then I just link too many and crowd out the main points#but yeah those four tags have the bulk of the rants#Rey's tag post-tros became full of this kind of thing#because it's so important to what's wrong with the ST that she is totally irrelevant to the actual victory#which should have been the heart of the trilogy#and she learns absolutely nothing and is thus a terrible protagonist in general#anyway I was intimidated to answer this because I was so happy to receive it lmao#I feel like I'm screaming into the void with my crazed insistence that the Skywalker Saga be about the Skywalkers#and if you don't want to write that then JUST DON'T???#leave them alone????#you could have cameos from the OT characters and just leave their happy ending the fuck alone????#I'm still after all this time FLABBERGASTED that they didn't THINK IT THROUGH when making#HAN AND LEIA'S ONLY SON a fallen scion#and there are numerous people who work at LF still baffled by the idea people CARE about this#I JUST CANNOT#anyway my 'a tros ity' tag also has a lot of content#obviously always in relation to how much they fucked up

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clearing Out the Askbox

I never thought about this before but I can absolutely vibe with this-- powerful kickass Suicune ladies for the goddamn WIN

Rest under the cut!

YES YES YES!!!! He has the colors, he has the vibe, he has the mysterious parentage... Kusaka make it happen

They do make the perfect middle children: They’re in a transition period between arcs, are seriously underappreciated, and forgotten by just about everyone! /s

Tbh I don’t think the setting up RSE in GSC would be possible bc the volumes for GSC were already out by the time the end of RSE came out and iirc it got cut somewhat short? I could be misremembering but I wanna say there was some weird publication mishap that made him have to do what he did with Celebi and the snappy ending... could be wrong tho. Also I wish he just didn’t kill them in the first place? Having them be seriously injured has the same / close enough emotional impact without a weird Celebi copout. Also I don’t trust Kusaka to write grief well in the span of like.... 4 chapters, maybe less. As for the aircar swap thing: thank you!! It wouldn’t really work in canon, but I think it’s a fun little what-if

Depends on the arc, but in general I think the tone of the game’s music fits relatively well with everything. Sorry that’s a lame answer :(

Red is a paragon whose simple and heroic nature make him the ideal first protagonist. Green is the ideal foil, and though he tends to warp based on the plot and characters around him, every arc he’s in is improved by his appearance. Blue is a very complex and fascinating example of how trauma can change people, but her potential was squashed by FRLG. Yellow is the perfect example of Kusaka’s creativity and everything that makes spe great. Gold is the first and only absolute bastard of a protag and really balances out the rest of his seniors. SIlver probably has the best depiction of trauma in the series and has a subtle arc that stretches for 10 years of material, which works in his favor and makes him one of the most cohesive of the seniors. Crystal was introduced at a terrible time (though imo that’s not Kusaka’s fault) and has suffered from botched inclusion in arcs ever since, which blows bc she’s awesome. Ruby is a mess both in-universe and in terms of writing, but god this poor child cannot catch a break. Sapphire... honey I’m so sorry. Emerald got the best glow-up between original and remakes of any character thus far and is possibly the most outlandish character Kusaka has (and I love him for it) Diamond is kinda boring as a solo protagonist but really shines within the trio. Pearl is seriously underappreciated for the arc he went through during DP, but unfortunately as soon as that arc finished he sorta lost relevance... impearltance if you will. Platinum has a relatively common character arc for her archetype but gosh if she ain’t the cutest lil rich bitch you’ve ever seen. Black is the shonen hero done in the best way possible. White barely got anything in BW and then B2W2 have her so much, which is the exact opposite of every other character in the series. Lack is an asshole who learns nothing but managed to still have the biggest turnaround of fandom opinion in spe probably ever. I can’t remember much about Whitley other than “she’s baby” so let’s go with that. X is way less “soft boy” than people claim he is, though tbh the snappy brooding dexholder is something we’ve been needing for a while. Y is the most leader oriented dexholder we’ve been in a while and quite possibly the first one to be based on the player character, but despite that she still gets a taste of FDS in the finale. Sun and Moon are wasted potential personified and I will forever be bitter about how two of spe’s most interesting characters got fucked over so badly by the plot. I can’t describe Sou or Schilly because we’re only 1 volume and it’s impossible to predict where their arcs are headed.

I was gonna say “what the hell are you talking about” but then you explained it in specord and it actually makes perfect sense. He reminds me of that one Gen Z “nothing matters” meme

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ascendance of a Bookworm Review

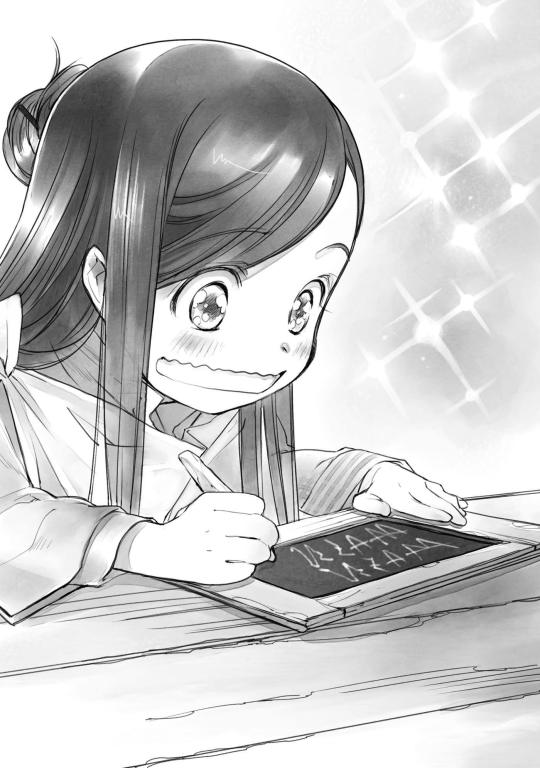

Ascendance of a Bookworm is an isekai light novel written by Miya Kazuki and illustrated by Yu Shiina. It follows Urano Motosu, or rather Myne as she is known in her new world, as she pursues her one true passion: books. In her past life, Myne had just graduated college and was set to start her dream job as a librarian until an earthquake hit while she was in her book-filled bedroom and she was crushed to death by her massive book collection. As her consciousness fades, she wakes up as the 5 year old sickly Myne in a world where paper is made of parchment too expensive for anyone but nobles to buy and use.

It's anime adaptation has two 14 episode seasons. The first season aired in Fall of 2019 with the second closely following up in Spring of this year. Both the anime and light novels are incredibly enjoyable, but I will actually be focusing this review on the light novel series as I found that I prefer it over the anime. That's not to say that the anime is bad. The light novels simply offer a lot more detail and depth to the already detailed world building that appears in the anime.

As you can see, the anime adaptation’s animation and art style is not much to look at. It certainly is not a sakuga filled series, but it does have its charm. Personally, it reminds me a lot of late 2000s series and fills me with a sense of nostalgia whenever I watch it. The art style is quite cute and simple. The light novel’s illustrations are similar, but have a bit more detail and shine to them. As is also true for the characters, world-building, and writing in general.

Given how detailed and intricate everything about Bookworm’s writing is, you may be surprised to know that the series is heavily character-driven rather than plot-driven. With a world as detailed as this, one might expect it to be filled with political intrigue and plot-driven drama. However, our main character, Myne, is so incredibly defined by her straightforward desire to have and read as many books as possible that there’s simply no time for the writing to expand on plot-driven story beats. As proven by when some volumes add more plot-driven story beats and end up being longer than usual.

With all that said, Ascendance of a Bookworm is very slow paced. In a series about making books, the anime doesn’t even give Myne paper until episode seven and proper books aren’t produced until later in the second season! That may make some people turn away. If you like your fantasies to be action packed, then Bookworm may not be for you. Even so, I implore all of you to give this series a shot. The slow-pacing does have its pros for readers looking for that sweet sweet cathartic feeling. Miya Kazuki has a talent for knowing the exact time and place for when certain things about her world should be revealed. And as such, she has developed a writing technique that reaps all the benefits of an isekai story while also not making it jarring for the reader.

By that, I am referring to exposition. Isekai stories have protagonists that know nothing about the fantasy worlds they live in, but with all the knowledge of their previous world. This gives authors the excuse to have the main character ask questions that the world’s inhabitants know as common sense, but still have things explained to the audience. If authors aren’t careful, these exposition dumps can be boring at best and immersion-breaking at worse. But Miya Kazuki has created characters and a world that creates perfect circumstances for seamless exposition.

First, we have Myne or Urano Motosu. A bookworm among bookworms. With a one-track and somewhat forgetful mind, all she knows and loves is books. She is an absolute delight of a character and while her development is just as slow as the story’s pacing, it is a wonderful experience to read it all unfold. Her desire for books leaves her selfish and uninterested in everything else, which does her no favors. Myne is a low-class peasant. Born the daughter of a soldier and seamstress, she already shouldn’t know much about the world outside her lot in life. But to make things worse, Myne’s body is very sickly. Racked by a mysterious fever that has forced her to practically spend all her time inside and thus, doesn’t even have the knowledge of most kids in the same class.

Her first real source of knowledge about the world she’s been reborn into is Lutz. A neighbor and youngest son of four, whose perpetual hunger and desire to eat the tasty food that Myne makes leads to him becoming close friends with Myne. Lutz is with Myne throughout her entire journey and learns just as much as she does about the world they live in. Afterall, Lutz is also just the kid of a low-income family. The life Myne was born into not only serves as a fantastic way to immerse the reader into world-building, but also ends being a great vehicle for exploring the issues of a heavily class-based society. Even in this world completely separate from our own, somehow Miya Kazuki manages to make some pretty bold commentary on class-based society as a whole.

Most light novels use fairly simple language, but even knowing that I think Miya Kazuki's writing style is even on the simple side of that. I don't blame her for that though, since her world and characters are so incredibly detailed that if she used flowery prose, her series would probably be the biggest and longest light novel series ever made. Some may not like how her style leans more toward "tell don't show" but it is still an incredibly well-written story with very compelling characters. Not to mention that this simpler writing style lends itself to some really great comedy.

That being said, Miya Kazuki’s writing often does that weird thing that happens in anime where something happens on screen and then the characters say out loud what just happened, except in written form. Which sounds terrible, but actually works a lot better in practice. It allows character interactions to flow a lot more freely and the simplistic writing allows for a lot more detail to be added. And due to Miya Kazuki writing the characters the way she does, there’s no boring or immersion-breaking exposition.

This writing style is not a product of the translation either. I have had the absolute pleasure of picking up (searching up) the web novel and experiencing Bookworm in Japanese as well. And as a side note; if any of you are upper-intermediate Japanese learners and are looking for Japanese reading material that’s simple enough for you to understand most of it (not mention fun to read), but also offers a bit of a challenge then check out Ascendance of a Bookworm’s web novel here: https://ncode.syosetu.com/n4830bu/. Bonus tip: Download the yomichan and/or rikaikun extensions on your browser for optimal reading time. Anyway, I can assure you that the translator behind Ascendance of a Bookworm is not muddling the writing style or the reading experience in the slightest. Miya Kazuki’s story and writing style comes through very nicely in the official releases.

Ascendance of a Bookworm is one of the most thoroughly realized stories I have had the pleasure of reading and watching. The anime is, of course, quite good, but I also highly recommend the light novel series even if you’ve seen the anime three times over. Miya Kazuki is an amazing writer and the official translations are quite good. If you’re like me though and like to binge series as quickly as possible, you might find yourself waiting aimlessly for more when you finish the anime and current English light novels. If you’re of intermediate or higher Japanese level, you can always read ahead in the Japanese web novels. Or you could seek out similar series. I recommend everything written by Nahoko Uehashi. Her novels are similarly well-realized fantasy stories with anime adaptations. Or, more obscurely, check out the fantasy series, Saiunkoku Monogatari. Its animation and art style gives me a similar sense of nostalgia and also has a great story with compelling characters. Anyway, I hope this review helped to convince you to give Ascendance of a Bookworm a shot, whether that be the anime or light novels.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rogue One or Why I (Probably) Won’t Watch This Movie Ever Again

It’s not as if I disliked “Rogue One”. I found it excellently made, from the political, philosophic, psychological point of view as well as with regard to settings, action scenes, acting, music, effects etc.

But why didn’t anyone tell me how deeply sad this story is?

“Rogue One” tells the story of a group of persons who all, for different reasons, have nothing left to lose and thus sacrifice their lives to help the Rebellion against Palpatine’s Empire. There is no reason for us viewers to get attached to the members of this crazy suicide mission: it is their destiny to die and we can sense that right from the beginning. Personally, I never felt compelled to root for them, I only felt terribly sorry for them.

It sure is interesting to be confronted with the reality that so many heroes gave an important contribution to the end of the war but never got anything good from it; also, how bleak and dangerous their lives in this totalitarian Empire were, constantly on the run, always oppressed, losing another piece of themselves over and over - family, health, mental sanity, safety, integrity, in the end life.

The only character I could feel with a little was Cassian, who stayed by Jyn’s side to the bitter end so she wouldn’t have to die alone. Jyn on the other hand never requited his feelings; her entire being was set on doing her father’s will, and Cassian, like everybody or everything else, was just a meaning to this end for her. (Though, in all honesty, she never compelled or manipulated anyone.) She may have been meant as a strong female character, but I didn’t find her in the least compelling or admirable. Jyn did what she had to do because she did not know what else to do with her life.

Jyn’s fate is a somewhat sarcastic take on the bond between child and father emphasizing that a father may give his child’s life direction and purpose but that this must not necessarily make him (or her, in this case) happy.

What baffled me most, in retrospect, was the reaction coming from most Star Wars fans. Long before I had watched the film, I had heard respectively only read of enthusiastic responses, usually culminating in “A real Star Wars film again, at last!”

Of course setting and design remind very much of “A New Hope”, because the story is set shortly before; and for brief periods we see the Death Star, Governor Tarkin, Leia and Darth Vader.

So then, this is what fans want, this is allegedly “real Star Wars”? Excuse me, depressing? Not the aesthetics and the message of the Prequels, the energy and drive of the classics or the new impulses and hopeful glimpses of the Sequels? Does it only depend on cosmetics whether a film is defined “real Star Wars” or not?

This whole story is a tragedy. It’s not a call to adventure with a happy ending like “A New Hope” or “The Phantom Menace”, a Greek-style drama like “Return of the Sith” or anything of the sort. It’s supposed to bring home that there is nothing wonderful about war and that everyone involved will lose much more than they win. This also fits to one of the Sequels’ themes, when we meet the old heroes again; they had won a war and founded a family - but before that, Luke and Leia had lost their old families, Luke had to give up his dream of becoming a pilot, and all of them suffered through tremendous physical and psychical horrors. And, as we learn, after a period of peace they had to watch their victory go up in smoke again as the embodiment of their hopes, their son and heir, nephew and pupil, turned his back on them and devoted himself to becoming evil like his grandfather, the very person they had fought against respectively tried to rescue and redeem all of these years before.

Yes, in a way “Rogue One” is “real Star Wars”. There is a person with father issues at the center, it’s an authentic, honest story, the characters are well-developed and the narrative is well thought out. But I was left almost in tears thinking how the hope Leia expressed in the last scene was founded on the absolute lack of hope of the protagonists of the crazy Death Star mission. I felt depressed for two days after.

Even “Revenge of the Sith” doesn’t make me feel that bad when I watch it, though the outcome is so terrible. There is Padmés funeral scene that leaves the viewer space to mourn, and the scenes with the twins and their surrogate families announcing that not all is lost. “Rogue One” just makes a quick cut when all is said and done and that’s it.

No one will ever think about these persons ever again, no one will mourn them, no one will be grateful to them or call them heroes. A brutally honest take on war and rebellion, opposite to the end of “A New Hope” where the heroes are celebrated and seen as such, though they are responsible for the death of everybody who lived on the Death Star. (Not that I’m blaming them, in that situation it was either destroy them or be destroyed.)

Luke Skywalker, hero of the first classic film which directly follows after this one, never knew his parents, lost his foster parents and his mentor during the course of a few days, but he joined the Rebellion and thrived on it. For Jyn, the loss of her family is a dead weight which hangs on her shoulders until it leads to her death. Jyn merely survives, making one heavy step after the other; she never rebels and goes her own way like Luke did.

I was also surprised since I had heard that Jyn was supposed to be a strong-willed woman, designed to be a role model to female spectators. I wouldn’t want any girl to choose Jyn as a personal example to go by: she is a cold, cynical person whose life never knows fulfilment, not a symbol of hope but of relinquishing of life, hope, happiness.

Her characterization is particularly bitter when we compare her to Han Solo, to whom Star War’s second spin-off was dedicated two years later. Though Han has a sarcastic streak, he remains generous and humorous, and he always cares and is cared about by someone. Despite his name, he is never really alone: he bonds with Qi’Ra, Chewbacca, Lando and Enfys Nest, while Jyn never is close to anyone. (Is it a coincidence that the names “Han” and “Jyn” are so alike, I wonder?)

Also contrarily to Jyn, Han turns his back on his father figure Beckett, deciding to go his own way. And in both cases, this attitude is not heroic in the conventional sense, but personal; Jyn does her father’s will because she feels committed to him, not to some greater cause. Han, too, rejects Beckett when he feels personally betrayed and let down by him. No wonder Han, as we get to know him in the classic films, is the most independent and worldly-wise of the characters. He initially had no father figure, then he found one but in the end, he chose to do without him. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence, when Han kills Beckett in self-defense, that his last words are “You made a wise choice”.

The difference between Han and Jyn, or also Luke, Anakin and Rey, to name other Star Wars heroes, is that he doesn’t have a father figure but he also doesn’t look out for one. He gladly befriends Beckett who is more experienced than he, but when he finds he can’t trust him he turns his back on him, with regret but not mourning him for long.

Han never knew where he came from, but with that also came the freedom to make his own choices; and as we know, contrarily to Jyn he still had a long and fulfilling life and found real friends, a home and a purpose. Very fittingly, “Solo - a Star Wars Story” is a feelgood film and not in the least depressing.

In both cases, we have a very realistic and not at all starry-eyed outlook on what “heroism” and “fighting for a just cause” means. Star Wars remains true to itself by hammering home all over again that it is not at all gratifying to be a lonely hero, and that on the other hand having a family may be a good thing, but being defined by them is a crushing burden. Picking up that burden and doing what you believe you have to do in order to feel connected to them may lead to the desired end, but then the question arises whether that end is really so desirable if the cost is so high. Again, Star Wars is not about the good guys blowing up the bad guys, but about growing up.

Luke Skywalker never knew about his family for a very long time, and after he had learned about it his father died, leaving it to him to repair the damage Vader had caused together with Palpatine; and as we see him again in “The Last Jedi” his character shows a bitter parallel to Jyn - lonely and disillusioned. This also follows the line of the Prequels: even if you have the best intentions you may still err, and deciding to give your life to what you perceive as a higher cause may literally become your, not exactly happy, fate. Becoming a Jedi master Luke became emotionally detached, which brought to the downfall of his temple; only when he communicated with someone again - Rey, Yoda, Leia, and also with his nephew a little - his existence gained new purpose.

In his last moments, Luke announces that he will still be there as a Force spirit; and after death he is remembered by many people in the galaxy, whether they knew him personally or not.

Jyn and Cassian die in the blaze of the Death Star fire, giving up what little they still had or were; Luke’s death is illuminated by the light of the twin suns which this time rise instead of setting. He loved and was loved, that is why he will never be truly gone. Jyn, Cassian and the other members of the Rogue One mission are forgotten, despite the invaluable service they did to the galaxy at large. This is what “Rogue One” ultimately is about: complete, utter and inescapable loneliness.

So, thank you for the food for thought, “Rogue One”. But I don’t think I will watch you ever again.

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

The classic PlayStation RPG Final Fantasy VII is perhaps the most well-known entry in the long-running Final Fantasy series from Square. The game was an enormous success in 1997 thanks to its stellar production values, great cast, engaging story, as well as its technologically groundbreaking graphics. Players were exposed to fully-3D cutscenes the likes of which hadn't been seen before, meaning that the game made something of an impression on the players of the day.

RELATED: 10 Things In Final Fantasy VII Remake Most Players Never Discover

Of course, none of that presentation and polish would mean much were it not for the story and characters that keep players coming back to Final Fantasy VII. The game is home to dozens of memorable scenes burned into the memories of RPG fans forever, and there are so many in the running that it can be difficult to pick a favorite out of the game's main cast.

7 Cid: Making It To Orbit

Cid is an engineer with a short temper, but lofty dreams. His overriding goal is to travel into orbit around the Planet on one of the rockets he's built; a goal that has yet to come to fruition by the time the player meets this new character. Cid has an arrangement of convenience with the malevolent Shinra corporation; he sees them and their resources as his best chance at making it to space, and they need his engineering expertise to construct their rockets.

This changes, though, when it becomes clear that Shinra only wants to use the rockets as weapons to smash Huge Materia into Sephiroth's meteor, which threatens to destroy the Planet. Unwilling to let this come to pass, Cid and the party board a rocket bound for the Meteor, which unfortunately takes off with them still inside it. Cid fulfills his dream, but under different circumstances than he imagined. The view from space ends up being all he hoped it would be, though, and the view of the Planet inspires him towards its defense against Sephiroth.

6 Tifa: The Promise To Cloud

The iconic scene atop the Nibelheim water tower wherein Cloud resolves to leave his hometown and join SOLDIER is one of the most recognized in the game, mostly because it forms the simple foundation for Tifa and Cloud's relationship that will inevitably get far more complex as the story progresses. Tifa makes Cloud promise to come to her aid if she ever finds herself in danger, to which Cloud agrees. The moment marks a flash of innocence that the story will refer back to when things darken later on.

RELATED: Final Fantasy: Every Protagonist, Ranked Worst To Best

This scene is also impressively recontextualized later in the game when the player finally learns the truth of Cloud's past. When Cloud's status as a somewhat unreliable narrator is revealed, the player learns that not only was Cloud never actually in SOLDIER, but he was actually present at the destruction of Nibelheim as a Shinra infantryman.

5 Barret: Confrontation With Dyne

Barret's character design immediately invites an obvious question: what happened to the arm? Barret's signature weapon, a machine gun grafted to his arm, is also the mark of a guy who definitely has some history. Barret is also shown to be fiercely protective of his adoptive daughter in the early parts of the game, but he hesitates to reveal much about how the two met.

As it turns out, Barret has some pretty personal reasons for being somewhat reserved about his past. Before the party leaves the Gold Saucer, they come across the scene of a massacre that a witness describes as being perpetrated by a man with a gun on his arm. Assuming it to be Barret, the party travels down to the surface to confront him. Barret reveals that it was not him behind the killings, but a man from his past named Dyne. Dyne was a resident of Barret's now-destroyed village of Corel and the man who originally orphaned Barret's adoptive daughter. After this backstory is revealed, Barret has the opportunity to finally settle the score with the villain.

4 Red XIII: Statue Of Seto

Before making it to Cosmo Canyon, the party's genetically modified best companion, Red XIII, is fairly curt towards the main cast. He seems disinterested in the affairs of humans and is fixated on his goal of protecting the Planet from Sephiroth. That veneer starts to crack, though, once we learn the backstory of Red XIII's lost father, Seto.

RELATED: Final Fantasy: Every Main Villain, Ranked Worst To Best

Thought to be a coward by Red XIII for fleeing in the face of an attack from the warlike Gi Tribe, it is revealed to both Red and the player that Seto was not in fact fleeing, but advancing to defend another entrance to Cosmo Canyon from the invaders. Gravely injured by the poison arrows of his foes, Seto stood alone until the toxins overtook him and turned him to stone. Upon finding the petrified remains of his father, Red XIII's commitment to the party and the quest are renewed.

3 Aerith: The Death Scene

Although it might be the most spoiled character death in the wide world of video games, the fateful encounter between Aerith and Sephiroth in the Forgotten City remains iconic. Even if a player knows it's coming, Aerith's death scene is masterfully constructed from a presentation standpoint, meaning that it's still quite shocking and tragic for those who might have already been tipped off to one of the game's biggest plot twists.

Another reason why Aerith's death scene works so well is the believable reactions from the rest of the cast after the act is done. The monumental nature of the loss is immediately clear, and the audience gets to see Cloud emoting through his dialogue far more than he's normally prone to doing. Of course, none of this would work were it not for some other excellent scenes involving Aerith throughout the rest of the game, but her death scene stands out as one of the most prominent and shocking in the game for good reason.

2 Sephiroth: Also The Death Scene

While this might run the risk of gushing too much about the fateful encounter between Aerith and Sephiroth, it's worth pointing out that Sephiroth's merciless execution of Aerith is a huge part of what makes him work so well as a villain. Indeed, Sephiroth is among gaming's most recognized antagonists, with players remembering his sheer strength as well as his menace. Most of the early parts of the game are centered around the pursuit of Sephiroth by the party, but the player is typically only exposed to the aftermath of his actions, such as when the player comes across the remains of the Midgar Zolom.

RELATED: Final Fantasy: The 25 Most Powerful Bosses Officially Ranked

That all changes when he kills Aerith, though. Suddenly, Sephiroth is not just a mounting threat on the horizon, but a person who has done terrible things to the characters the player has come to care for. All of the buildup he receives pays off at this moment, giving both Cloud and the player a strong personal reason to continue the chase and to motivate them to ultimately destroy Sephiroth.

1 Cloud: The Final Omnislash

Sephiroth is without a doubt one of gaming's greatest villains; a feat which is absolutely essential to the structure of Final Fantasy VII, as most of the game revolves around the pursuit of said villain. Sephiroth eludes the player at every turn, interrupting their progress at each given opportunity and just generally making life miserable for everyone.

That is until Cloud and company finally catch up with him. After a grueling final dungeon and boss battle which tests the limits of what the player has learned so far, as well as the stats of their characters, Sephiroth is finally defeated in his ultimate form.

Not quite, though. Sensing further danger, Cloud plunges back into the lifestream of the Planet to attack what remains of Sephiroth with his ultimate move: the final Omnislash. In an extremely well-deployed cinematic, the player is given the satisfaction of seeing Cloud absolutely wail on this poor bad guy, slicing him into nothing with a flurry of charged strikes, instantly gratifying all of the efforts the player has made thus far.

NEXT: Final Fantasy XV: 10 Things About Aranea Highwind Fans Never Knew

Final Fantasy VII: Each Main Character's Most Iconic Scene from https://ift.tt/3vD6Mzl

0 notes

Text

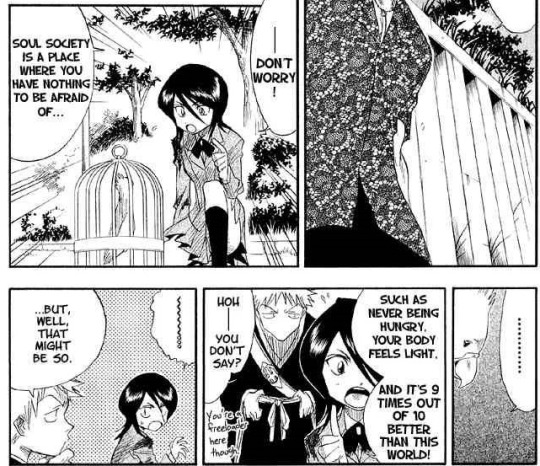

The Problem with Ichigo Kurosaki

Back when Bleach’s final chapter came out, the one thing that perplexed me most about the omnishambles that was the last arc was that Ichigo had taken over the Kurosaki clinic.

I’d long-since given up on a satisfying end to the series and was following out of morbid fascination more than any sort of interest. I’m not a shipper and the glacial pacing and empty pages killed any spectacle that might have been entertaining enough to cover the massive flaws of the series. I entered the Quincy arc with no expectations and still managed to be surprised by how little thought and effort Kubo put into his product. There was no personal investment left, so I didn’t care enough to get upset over how things ended up.

But Ichigo taking over his father’s clinic...that was a surprise. And through that I came to a startling realization that after almost 700 chapters and 15 years I still knew nothing about Ichigo as a character.

I want to be careful when writing this, firstly because as a self-admitted filthy casual I’m not nearly as familiar with Bleach as I am with most other things I write about. Secondly, while it’s a nice bonus I don’t think that every story necessarily requires a deep, super nuanced character driving it.

I’m gonna use One Piece as an example here because I think it fits well. Luffy isn’t a complicated dude. He’s well-rounded with clearly defined dreams and goals, but ultimately he’s your basic Shonen power fantasy. What sets One Piece apart from almost every other manga in existence is its world building, and by creating Luffy the way he is, Oda has made a main character that facilitates the exploration of his world.

Ichigo starts off well enough for the protagonist of a monster of the week-style battle manga. I think it’s pretty apparent that Kubo wrote Bleach by the seat of his pants, because a lot of early details don’t match what we see later in the series.

...

...

...

And, again, this type of writing can be done, but it has to be done carefully because without forethought it’s really easy for plots and characterization become a muddled mess.

Early Ichigo stood out from other mainstream manga protagonists. There’s a mature edginess to early Bleach, and a strong aesthetic that highlights one of Kubo’s greatest strengths as an artist: drawing really cool shit. Ichigo isn’t a hyperactive goofball, in fact he gets pretty good grades and is generally regarded as being a reliable - if grumpy - guy. His backstory isn’t exactly groundbreaking, but again, having a main character that’s hellbent on protecting others is exactly the sort of protagonist that can drive a monster of the week-style story.

More importantly, at this point in the story Ichigo has agency as a character. In chapter 2 of the series, Rukia demands that Ichigo fulfill her duties as a soul reaper while she’s out of commission. He initially says no, but quickly changes his mind when he sees a cute kid almost get eaten. Ichigo agrees to help, but on his own terms. In his own words, he’s only paying off a debt.

Fast forward to chapter 25. Ichigo has survived his encounter with Grand Fisher and had a nice little heart to heart with his dad. He makes the above declaration, effectively choosing to continue on as a soul reaper even after Rukia regains her powers and his “debt” is paid.

What makes the Grand Fisher fight effective is that it highlights how much growth Ichigo needs to undergo, not as a fighter but as a character. It is vitally important for a battle manga not to have fights for the sake of fights, or even because they’re demanded by the plot. A good fight conveys story and develops characterization - a clash of ideals as much as swords.

The problem is that this doesn’t really go anywhere. Ichigo’s gotta protect them all nature suits shorter, one-off arcs but isn’t suited for the long, sprawling epic Bleach would become. The scope of Bleach’s world and story expanded, but Ichigo stayed the same. Or rather, he devolved into something lesser.

Ichigo’s goal to protect those he cares about is problematic in two ways:1) it requires someone to need protecting, and 2) it’s reactionary. This limits how much influence Ichigo has on the plot as a whole. It’s no wonder that the Arrancar saga is copied wholesale from the Soul Society arc because rescuing people from danger is literally the only thing Ichigo ever shows interest in doing.

Instead of taking the time to develop Ichigo as a person, Kubo instead has to create increasingly-ridiculous ways for him to play a part in the plot. This has the unfortunate side effect of making Ichigo literally everybody’s pawn to be used and manipulated in whatever way it takes for the story to get from Point A to Point B. I would think by the time Yhwach comes around he’d be sick of it, but all Ichigo is capable of doing is react, react, react, often looking very surprised when someone plays him like a fiddle yet again.

And maybe to compensate Kubo gives Ichigo a mishmash of powers and abilities, but ironically the more things that are added to Ichigo’s moveset the less unique and special each one becomes.

It’s kind of like mixing colors. Red and blue together make purple but if you add yellow and green and orange along with it, in the end all you’re going to have is a brownish sludge. Ichigo starts the series as a human-shinigami hybrid. For the sake of brevity, I’ll call this version of Ichigo a humigami. As a humigami he has basic swordsmanship, immense spiritual power, and the ability to follow spirit ribbon thingies to find people. So far so good.

But with the introduction of the Soul Society and the massive influx of characters, Ichigo is no longer The Special. Kubo has two choices here: further develop Ichigo’s shinigami powers or add something new into the mix. Kubo elects to do both, and Ichigo gains his hollow masks AND learns bankai in a matter of days.

Now a human-shinigami-hollow (humagollow for short), Ichigo saves the day only to get curb-stomped by Aizen. The post-Soul Society chapters would have been a good place to do some old-fashioned character development, but while there is some nice closure chapters nothing really changes before the next major arc kicks in.

Put yourself in Ichigo’s shoes here. You’ve gone through the gauntlet to save a friend from her execution, witnessed the slums of the afterlife, fought several life or death battles against an organization who keeps, among other things, genocidal maniacs in their employ. You’ve seen corruption, you’ve seen conspiracy, you’ve seen a totalitarian regime that insists on following the letter of the law over common sense and justice. You’ve lived your entire life striving to protect those weaker than yourself and the last several months sending spirits to what you thought was a peaceful, idyllic afterlife.

Would you leave the Soul Society in good terms? Would you consider them allies and fight their wars? Would you be okay with leaving your friend, who you risked life and limb to save, in the very environment that wanted her dead just days before? Would you not have questions and demand answers?

Apparently not, if you’re Ichigo Kurosaki.

Fast forward again to the introduction of the arrancar and visored. It’s about this time where Ichigo loses everything that made him unique as a character. A whole host of characters are introduced that have a mix of shinigami and hollow powers (which, despite ostensibly being antithetical to one another are functionally identical) and it’s revealed that Ichigo isn’t even the only shinigami in his family.

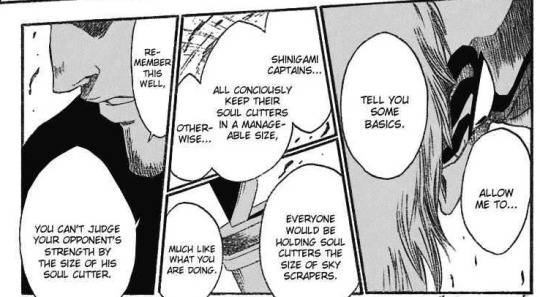

Isshin’s fight verses Grand Fisher becomes especially egregious when we the audience get this little tidbit about how all high-level shinigami compress their sword’s spiritual power into a smaller form

because back when Ichigo first showed off his bankai one of the notable things about it was that it was kind of tiny - a direct contrast to how most releases worked.

It’s the same for all of Ichigo’s other attacks. His bankai is supposed to boost his speed to incredible levels, but he’s constantly out maneuvered by enemies, the surprise attack from behind being a Kubo specialty. His main ability is nothing but a giant energy slash, easily replicated by a shinigami’s kido or a hollow’s cero.

By having Isshin steal the Grand Fisher fight from Ichigo, Kubo robs his main character of a chance to show off how he’s changed since the early part of the series and robs him of his uniqueness as a fighter. The fight itself is not good, memorable, or fun enough to counterbalance how much the author is crapping on its protagonist, a trend that unfortunately gets worse as time goes on.

Anyway, through training Ichigo becomes a human visored (hisored) and goes off to Hueco Mundo to kick ass and get his ass kicked in about equal measure, and once again questions are brought up, if not explicitly than implicitly through the course of the narrative, that are never even addressed.

1) If it weren’t already obvious, the Soul Society cements itself as being absolutely terrible by its treatment of the visoreds. Are they really the good guys here, and why is no one trying to reform their more archaic and barbaric practices?

Unfortunate Implication: Ichigo is willing to ally with complete assholes to accomplish his goals. The whole “protecting those who can’t protect themselves” schtick only applies when people he cares about are in danger.

Conclusion: Ichigo is kind of an asshole, or at least apathetic to the plight of others, a direct contrast to his characterization thus far

2) If hollows are impure spirits, and high-level hollows spirits who have evolved by consuming countless others, would it not be in the best interest of Nel and other “good” arrancar to be purified? Is it even appropriate to think of hollows who have evolved as individuals or a conglomeration of all the souls that have been consumed? Are hollows inherently evil, or has the Soul Society’s understanding of the hollow/non-hollow spirit dynamic been flawed this entire time?

Unfortunate Implication: Either Ichigo doesn’t think through the logical conclusion of having hollows as allies enough to question what he’s been taught about hollows thus far, or he’s okay with leaving countless spirits in an impure state and damning them to a miserable existence of insatiable hunger and denying them access to the proper afterlife/reincarnation cycle

Conclusion: Ichigo isn’t as smart as he’s presented to be, or he’s okay with making friends with the very monsters he’s sworn to destroy...as long as they’re cute and helpful

This is what I mean when Ichigo devolves as a character. By the time the Fullbringer arc rolls around (for those keeping score at home, Ichigo has gone from hisored to fullbringer back to humigami) Kubo has built a world full of shades of grey, but continues time and time again to have Ichigo play it as if it were black and white. The reveal that Ichigo is, in fact, a quincigami is just the icing on the cake, stealing the one thing that made Ishida unique only for it to go absolutely nowhere and confuse an already muddled backstory.

All of these changes in power and the complete disregard for the moral quandaries brought up by the story mean that any change in Ichigo is superficial, like a skin change in a video game. He might look cool and give his attacks spiffy names, but it’s all an excuse for Kubo to draw him in different outfits because once again, all Kubo really cares about is drawing really cool shit. Everything else is secondary. Nothing has to make sense. Who cares about Ichigo’s hopes and dreams and desires when he can have two swords that he’ll never use in battle. Oh, it’s the epilogue and Ichigo needs to be a grown up doing grown up stuff...might as well make him a doctor. It was good enough for his old man, right? It wasn’t as if he said anything against taking over his father’s clinic some day.

Then again, Ichigo never said that’s what he’d like to do either. Almost 700 chapters and 15 years went by and Ichigo never once said what he wanted to do with his life when he grew up.

And that, my friends, is a problem.

#Bleach#Manga#Analysis#ichigo kurosaki#character analysis#character development#bad character development#writing#creative-type analyzes

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

So apparently the book does a better job of supporting Alina's reluctance to take up the Call of Adventure (ie, embrace being the Sun Summoner) because of how the role would be othering and isolating, a great fear of hers. That's legit and since I haven't read the book yet, I'm going to pass on commenting on that.

But the show in later episodes actually makes sympathizing with Alina's reluctance harder, which is shocking to me given that usually more information helps flesh out a character's motives and thus my sympathy for them. Except in this case there's a scene later when Baghra snaps at Alina, asking how many more children need to be orphaned by the war before Alina embraces her role as a figure who can legit save this country from a terrible affliction, and you know what? It's a great question! It's a question I'm absolutely flabbergasted was even necessary to pose to Alina, an orphan of this war!

On the one hand, if you told me that Alina was off minding her own business, living as a victim of Ravkan racism and thus just didn't give a fuck about Ravka and didn't care about the Fold one way or the other, certainly not enough to put herself and her loved ones in the crosshairs of powerful people trying to use her, I could actually accept that as a reason for her reluctance that's related to her fears of othering and isolation.

But Alina joined the army. Armies are not generally known for failing to instruct their personnel on the importance of the cause they're fighting for. So even as skilled labor, a cartographer, I am struggling to believe that the suffering caused by the Fold wasn't at the forefront of Alina's lived experience for years. I'm struggling to relate to someone who could see that level of suffering, including the fact Mal has been drafted into this war and will presumably keep fighting in it until it ends, learn she could end it, and not on some level show eagerness to help out. Eagerness that could then be drawn up short when she learns of darker forces at play and the fact that her powers are not necessarily going to be used for that purpose. That's totally fine, and indeed maps nicely to an arc of heroic idealism running up against complex realities, which jives well with the character themes of S&B in general.

It just strikes me as a ludicrously privileged and/or milquetoast character beat, a paint-by-numbers grafting of Alina onto the traditional Hero's Journey with the required beat of "resisting the call to adventure" that she learns of her powers and needs to be reminded that she could use them to help people because otherwise she does nothing but whine about Mal and try to run away! Nina doesn't shrink from the call. Inej doesn't shrink from the call. They're immensely skilled women with morals that drive them into danger so clearly it's not an issue of Alina being a female character.

So I'm just incredibly puzzled as to why Alina, who is presented as our central female protagonist upon whom the whole story hinges, doesn't have the same grit and drive as those other women. Why she needs to be coaxed into embracing a situation that, at least initially, presents her with the possibility of ending the war that risks getting her and her loved ones killed every day and kills the parents of other children like her. Why does Baghra have to remind her of this? Why wasn't this central to her character's journey? Why wasn't the arc that she needs to temper her idealism with strategy and maturity? Why do we have to suffer through beat after beat of her pining after her childhood boyfriend and trying to get back to him and her tenuous status quo? I'm not saying it isn't realistic it's just not someone I give a fuck about if they don't give a fuck about anyone else's suffering until it's literally shoved in their face to care, just so they can go back to their status quo!

Christ, I know it's realistic for someone like Alina to "resist the call to adventure" as per the standard hero's journey beat, given how she found herself a textbook Chosen One, but the sheer level of threat the Fold poses to her country kinda makes me wish she was a little more enthusiastic about this destiny that just got thrust upon her. That and the fact she hasn't been able to do much in the story so far except cry and cringe from danger has me rolling my eyes to some extent and just wishing desperately for her to be a more "modern" heroine who actually leaps to the call instead of worrying about how she's going to get back to her childhood boyfriend, for goodness sake.

#alina get your shit together#yes she gets better but omg I can't believe she needed to be REMINDED OF THE WAR SHE COULD STOP#THE WAR SHE WAS LITERALLY FIGHTING IN#BY A PRIVILEGED OLD LADY WTF#maggie watchs sab#shadow and bone liveblog

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

LET’S TALK ABOUT HOW GOOD SHIN SEKAI YORI IS

FUCK FRIENDS, YOU KNOW WHAT I LOVE

I LOVE SHIN SEKAI YORI

I will try to tell you about Shin Sekai Yori without spoilers so if you want to go watch it yourself (it's on Crunchyroll! and probably other legal streaming sites!) you can do so without spoilers. I do think with as little spoiling as possible is the best way to approach this show.

But also I want to talk about all of the spoilers because it has one of the best meta narrative arcs of anything ever for me, and I think is ultimately a fantastic example of perspective and why I think the idea of the 'unreliable narrator' is kind of silly but rather that all characters should have their own biases and stories need to be regularly considered in the perspective of all characters.

SO HAY FIRST OF ALL, WATCH THIS COOL AMV, IT DOESN'T HAVE SPOILERS BUT IT LOOKS GREAT AND IT SHOWS A LOT OF THE NEATO ART:

youtube

(IF YOU LIKE IT, GO TO THE YT CHANNEL AND LEAVE A COMMENT)

So obviously Shin Sekai Yori gets pretty fucked up, but it starts off quite idyllic.

SSY is the slow, careful, and detailed deconstruction of a fantastical utopia. A series that doesn't so much rip it apart at the seams but just stretches it far enough that you can take a look at the stitching, then lets it settle back into place.

I really like this, but it's brutal in a way that a lot of deconstructions of this nature aren't, but I guess that is getting into spoiler territory.

SSY is told in chunks following the life Saki as she grows up to become a leader, so first and foremost I like it because it's the sort of story often allowed men but distinctly given to a young 'ordinary' girl here. The first part of the story is told with her and her friends in elementary school, and it follows them as they go into their teen years and find their places in society.

Obviously the whole POINT of a utopia in a narrative like this is that it isn't perfect, and I think the story does a great job at how it introduces the flaws of the world. Because you start following the kids AS kids, you get a child's perspective on their reality. A lot of complex issues seem simple, a lot of alarming things are overlooked while other things are fixated on because kids haven't yet been as indoctrinated as adults and you still see their moments of disbelief and alarm at the sort of shit that will eventually become part of their world.

The world itself is not one of technological perfection but a sort of homey naturalistic type. It's a universe where everyone has psychic powers, and the community is small and tight knit enough that you can know all of your neighbors, grow up with the same group of kids your whole life, and never have to fear violence or danger. Humanity has more or less overcome having a discernable caste system, there is no obvious poverty, no outcasts. Children learn about their world with a careless sort of freedom and are taught fables about times in human history where everyone didn't do their best to look out for each other. It's taught and understood that you don't indulge petty emotions and in a time of trial, you sacrifice yourself for others.

It is, by all appearance, a good world where everyone can be happy.

And it's fairly believable, even.

The story itself is about how this world was created, why the choices that were made were made, and the past and present costs of creating such an idyllic world. We learn about it all alongside the protagonist as she grows up and discovers more about the intrinsic flaws in the systems that has governed her life and determined the fates of people she cares about.

And that's really the absolute furthest I can go without spoilers. SO IF YOU HAVEN'T SEEN IT AND WANT TO DO SO. GO FUCKING DO SO.

Now time to discuss spoilers. UNDER THE CUT:

So here is the thing, the thing I fucking love about SSY.

It never fixes the world.

Saki learns every facet of what is wrong with their system and doesn't become a revolutionary.

Which is what I mean about how it's a deconstruction that doesn't deconstruct in the sense that it takes it apart, it just shows you how it was put together and then with brutal honesty admits that we all like it better when the beautiful fantasy is in place.

"We" being the privileged ones who benefit from the construction.

One of the things I love is the careful design of the entire world and how everything kind of slots up against each other to form fantasy construction that I find quite believable and extremely interesting. Let me see if I can remember them all.

All humans have psychic powers which make them incredibly strong, nothing can challenge them but another human.

But because the strength in psychic abilities can vary so widely, it's possible for one psychic with too great a power to rule in a terrible dictatorship, to stop this, humans found a way to actually make themselves allergic to killing each other.

So if one human kills another, or rather, PERCEIVES they have done so, they will feel so much miserable empathy they will themselves die. It's called the death of shame.

This works pretty well except for the rare but possible outliers: what if for some reason a human can't feel empathy? What if a human doesn’t develop psychic powers and thus isn’t bound by the rules around them? They would be able to kill indiscriminately and more over, other humans wouldn't be able to protect themselves with lethal measures.

So you need to make sure only children who fit within certain parameters make it to adulthood.

For the good of protecting society, then, it makes sense that children are not considered individuals possessing their own rights until they are eighteen. This means not only can you kill them, but you can freely fuck with their memories without it going against your society's established morality. You're protecting the world from potential destruction, after all, but it means anyone who makes it into adulthood can be trusted with phenomenal cosmic power. How ELSE do you raise a species of super powered beings?

Then there's the monster rats, sentient creatures created by humans to serve humans. Because why have phenomenal cosmic power if you have to use it to do all of the boring day to day chores?

The best way to get rid of the class divide is, of course, to create another species to handle the work of the lower class for you.

Just tell them you're a god.

And if some of them don't want to work for you, it's religious warfare when you order the ones who do believe you're god to wipe out the others.

But what happens when monster rats start reading about human history? Start learning from your texts? Discover you are not gods just beings with a different, more advantageous skill set, with a longer history to have learned from?

And what happens when they get ahold of a human child and raise it thinking it's a monster rat?

SSY ends with Saki, our courageous, tactical, considerate, tenacious protagonist having a conversation with the tortured and deformed body of Squeara, a monster rats she'd met as a child and seen grown into a terrifying revolutionary who justifiably hated humanity for forced enslavement of his entire species.

She knows.

She knows more about their society and its inherent flaws, who it hurts, and why all of those choices were made than probably anyone else alive. She knows the monster rats personally as well, and has seen that they are smart, capable, that they have feelings, fears, flaws. That they are no less than humans.

She knows they were created by introducing mole rat DNA to the last of humanity that never developed psychic powers.

She said herself that for the number of monster rats they had killed, they should have died the death of shame thousands of times.

Yet, while Squeara's tortured and still living remains rest in a jar, on display in a memorial as penance for his crimes against humanity, she she wistfully reminisces over the first time they met.

Then she mercifully kills him.

Because she can understand monster rats, she can know their origins, she can see who they are people, she can pity them. But she can't see them as human. And the death of shame isn't about reality, it's about perception.

And in fact, not seeing them as human is an essential component of her status above them, not just as a member of the privileged caste, but as a future ageless leader of their people.

And the show ends on a hopeful note. She wants to build a better world for her child. She believes that humanity can change. From her personality we know she will seek out the truth, and try to make good choices that balance both morality and the future of her people. And she pities the monster rats, she wants to take care of them, I don't for one second doubt that she wants them to have a better life in the future as well.

But she isn't willing to tear down society as it stands to achieve it, she isn't even really willing to be particularly disruptive. She wants to make the slow and subtle changes necessary to improve the world that they have, not rip up anything by its roots nor shame the people born into this world for the advantages it has offered them.

And you understand her, because you saw her learn every piece of information up until this point. Maybe you want to believe it’s not what you would do, but you can understand why it’s what she does.

It's not the story we usually get, or at least not the story I grew up on.

When you grow up in a utopia only to discover it is built on a network of lies and hypocrisies that cause some group to suffer so that the privileged can maintain their comfort, the next step is anger, resentment, betrayal, revolution. Within a generation one society is crumpled and the hope is that a better one will be built in it's place.

SSY shows that story from a different perspective, one that is I think less naively kind and optimistic about the likelihood of privileged people, if given all of the knowledge, power, and opportunity, to upturn their own lives, sacrifice their comforts, their position, in favor of doing 'what is right'.

It is in fact, brutally honest about the likelihood of such a person even really grasping 'what is right', of them even truly being able to empathize with people who live in such a different world from them that they fully recognize their humanity and connect with their deaths in the same way they would with someone they 'recognize'.

Saki is a good girl, a good friend, she's smart, thoughtful, empathic. You'd probably vote for her to be president. I know I would.

But she isn't going to upset the establishment. She's going to gently guide it toward a better path in marginal increments, and she will more or less sleep soundly with the understanding that change takes time, secure in the belief that life isn't inherently fair, but everyone is doing their best to bring about the best possible future.

It is, to me, an amazing character piece, and an amazing world building piece.

And I think it does something interesting that a lot of shows don't.

It gives you all of the pieces, but it doesn't tell you what to take away from it.

I think you could easily criticize the tone of the narrative and say it wants you to not be critical of Saki, to be proud of her, to think she is amazing, that she did everything she could, that she's a hero because she's the protagonist.

But it doesn't give you the pieces to that story, that's just what you get if you take 'protagonist' and the way she gets a happy ending and a hopes for a good future.

The pieces it gives you unilaterally are that monster rats are the same as humans, but that from the human perception they are grotesque, inexcusable, unrelatable.

Humans shudder in horror at monster rats for lobotomizing their queens to use them for breeding but humans murder and alter the memories of their children to weed out anyone not neurotypical or who doesn’t develop psychic powers.

In a scene that gives me chills, Squeara screams that he is human to a room full of humans who mock him and condemn him to a fate of eternal suffering, a fate that can only be bestowed by a god.

And then Saki, the merciful god, puts him out of his misery and in doing so proves that she never saw him as being human, right until the end.

She will do 'her best' to help the monster rats, to keep a promise she made. But she will always do it as someone who stands above them, can't be hurt by them, and may not ever see them as equals.

And I fucking love it.

#op me#shin sekai yori#media musings#anime recs#media recs#FOR REALS GO WATCH THIS ANIME#i lo v E#whispers i love it#it's my jam times a thousand#i just love protagonists who are deeply flawed#and how they don't ever truly overcome the world that produced them#that heroism and goodness is all a matter of perspective#ssy isn't actually terribly complex#but it sets up a simple look at a complex dynamic#and doesn't use the simplicity to sell you a simple solution#where if only there was a privileged hero to rise up#everything would change#everything would be better#squeara actually did#in the long run#probably have a huge impact on the future of his species#on any hope they might have to one day be equal to humans#but it won't happen over night#or in one revolution#or one generation#and it won't be either him or saki who achieves it#they will be pinpoints in a lengthy history between their peoples#they will be forgotten by society at large#and remembered only academics who care about such things#and the memories

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

FEATURE: Humanity's Worst, Front and Center on the Anime Stage

Humanity's Worst, Front and Center on the Anime Stage

By Ian Mertz

There is a sadistic thrill that comes with watching people acting against our ingrained sense of morals, or better yet, against society's standards of good in favor of our secret rebellious desires. When Lupin the Third came on the anime scene in the early 70's, with its titular pragmatic thief, it was a huge shift from the model of protagonists who embodied the forces of absolute moral good. Even the punks who so often popped up as the stars in early sports classics brought a bit of that wild side out in the show, let alone more aggressively amoral characters like the swashbuckling interstellar Cobra or the hitman Golgo 13. Flash forward to 2017, and as if an old otaku made a poorly worded deal with the devil we got a season of protagonists who moonlight as terrible human beings, with both hilarious comic headliners and bone-chilling pragmatists coming to call. These are their stories.

KONOSUBA -God's blessing on this wonderful world! 2

Back in the 80's and 90's, prominent writers such as Rumiko Takahashi and Yoshihiro Togashi noticed that if they wanted to make their protagonist funny, one thing they could do is make their protagonist kind of a dick. Characters like Yu Yu Hakusho's Yusuke Urameshi, Ghost Sweeper Mikami's Tadao Yokoshima, and Urusei Yatsura's Ataru Moroboshi were all generally moral people, but had many of the failings one would expect of a teenage boy: perverted, insensitive, and just generally causing trouble. Again, they had a baseline morality usually shown through their devoted love interest, who indirectly acted as their anchor, someone who brought out the best in our hopeless hero.

The first show on our list, KONOSUBA -God's blessing on this wonderful world!, tosses that morality out the window, and instead of a love interest just lets the whole harem get in on the amoral fun. Adventurer Kazuma Satou is just as lecherous and abrasive as any rom-com hero, but instead of a soft spoken heroine to bring out the non-existent goodness in his heart, he gets three companions at least as bad as him. It turns out having characters who are generally good on the inside is better for character development and storytelling, but when you take that away from them the result is plain hilarious, especially with the sense of comedic timing the show has honed over its last season.

Of the three the show mostly centers on Aqua, the goddess Kazuma forcibly brought on his adventures. She is the only one in the show with a tongue as sharp as Kazuma's, and neither of them will let the other's failures go unnoticed, nor their own successes go without a good long stretch of gloating. When Aqua purifies a great spirit rooted to the world against his will, she spends the rest of the episode reveling in her almighty powers as a goddess right in front of Kazuma's face; when it turns out the purification also set a horde of monsters upon the city in the process, Kazuma's insults bring her to the verge of tears.

The other two provide endless fuel for Kazuma's morally abhorrent personality too. While the masochistic holy crusader Darkness left the center stage for a while at the start of this season's KONOSUBA -God's blessing on this wonderful world! 2, she is back and in rare form, having gone so far into the realm of fetishizing her own pain and humiliation that Kazuma can no longer even insult her without feeding her complex further. The crowd favorite, the explosion junkie Megumin, has also been stepping up as perfect fodder for Kazuma this season. It's a mark of both great writing and the author's particular penchant for creating human trash when the show's greatest exposition thus far this season is that Megumin spent her younger years taking some kid's lunch money after class.

Masamune-kun's Revenge

And maybe it's a mark of a good anime season that she isn't the only character stealing people's lunch. One of the more popular romantic comedies this season, Masamune-kun's Revenge features a burgeoning couple who would be right at home with the KONOSUBA -God's blessing on this wonderful world! cast. I say burgeoning because they aren't a couple at the start of the story, nor do either of them like each other, and not in a simple Ranma ½ -style tsundere mismatch. Masamune Makabe wants nothing more than to be asked out by the school idol Aki Adagaki, who is notorious for hating men and rejecting them in cruel and mortifying ways. His motivation? To mortify her right back, the girl who teased him when they were kids. He completely reworked his appearance to the point where he's a heartthrob among the girls, but he passes up his chances at love for that one shot of sweet karmic justice.

And despite how comically petty he is for even trying, Aki sells herself as such a terrible person that we can't even blame him. Besides sticking all the boys who ask her out with insulting, albeit meticulously researched, monikers, she also eats both her share of lunch and most of her best friend's bread on top. Good for her that she eats healthy, but the self-absorbed way she orders her friend to buy her more food, away from the prying eyes of the other girls who respect her so highly, makes us want Masamune to take her down a peg too.

Or such is the premise. In reality while KONOSUBA -God's blessing on this wonderful world!'s cast is designed to be irredeemable, as we dive a bit deeper into Masamune and Aki we get to see a bit of their softer sides, on guard due to their past experiences (with each other), but prone to slipping up all the same. Masamune, focused on his revenge plot, learns through shoujo manga and botches his plans so often and so thoroughly that he ends up needing coaching from an insider in Aki's life. Meanwhile Aki is so clueless that she not only proudly wears cosplay to her first “date” with Masamune, but she derides him for thinking that that's wrong. As they both continue to hurdle towards ruining each other's lives again, the comedy and romance we're treated to is sometimes enough to hope they learn to be less petty and narcissistic, or it would be if it weren't so amusing to watch their misguided battle.

Saga of Tanya the Evil

But not all this season's terrible people are funny. Sometimes being registered as a terrible person implies something more akin to that title. Sometimes we are given a character who is genuinely morally repugnant, the kind of person who would get their family killed for a dollar and a pat on the back. These are the people outside the realm of 80's comedy; these are the people who would more likely show up on a police blotter, or worse, a thousand documentaries asking what went wrong. Thankfully in Saga of Tanya the Evil, it's easy to see what went wrong: someone gave that person a gun, a uniform, and an incentive to kill.

When even the title registers Tanya, a girl who was given too much power in the army as a result of her abnormally developed magical powers, as “evil,” there's a pretty clear message being sent to us the viewers. There is little to no room for sympathizing with her, which is made worse by the fact that we understand her completely. She is vindictive, setting up a group of soldiers who disobeyed her to be killed by the enemy in the next attack. She chooses every word to better her chances at staying safe and away from the front line, whether it be to her superior officers or to her friends celebrating a new birth in their household. We see her pushed to the brink of death in a fight, and we see the unbridled joy she feels at letting her powers loose on anyone who bleeds red and looks at her the wrong way.

But we also see her slip up, either tricked by those who are wise to her manipulative words or tripped up in her own ambitions. As Tanya is rising to power, the show is shaping up to be something we don't see to often in anime: a classic Greek fall from hubris. As we dive into her thought processes and motivations, we start to see all the fatal flaws that will inevitably come back to her, all the ways in which she won't learn from her mistakes while they're small. Besides the well-choreographed action and the detail put into Tanya's crazed facial expressions, the true gem of the show is watching Tanya's character, as a textbook case in greed, ambition, psychopathy, and if all goes well, in a fall from grace.

Scum's Wish

On that note, I would be remiss to not at least mention the crown jewel of this season's lineup of amoral characters. I read the manga for Scum's Wish a few years ago, and was thoroughly caught up in how shockingly awful—yet shockingly believable—the entire cast was. Each character sets out to outdo the last, while at the center lies a single doomed couple: Hanabi Yasuraoka and Mugi Awaya, the power couple of the school. To their friends and classmates both of them are perfect, and perfect for each other. But they share no love between them; both are only out to soothe their loneliness over loving someone else. For Hanabi it's her brother, a schoolteacher who has a crush on Mugi's tutor from afar. For Mugi of course, it's that very tutor, who seems aloof to the whole situation save for being very attuned to Hanabi's moods.

A love polygon develops with these four and a whole slew of their friends, each of whom is willing to use, bully, and manipulate one another to feel just a little less lonely in the world. Just as surprising as the explicit sexual encounters between the characters are the ways in which the script captures their thoughts, their disgusting and distasteful ways of getting one another to give up their other loves, their other friendships, even their mental state of being. It's not haphazard, nor is it solely a statement on the evil in people's hearts. It is perfectly balanced and calculated to show their desperation, and how they try to navigate love and friendship in the wrong way.

This season's adaptation adds an additional layer to the manga, namely framing it as tragic. In particular Hanabi's character flaws are downplayed in comparison to the other characters, and she serves as the main focus through which we see the story, which develops her character so well that despite having seen her original manga personality I even started to feel bad for her at some point. Soft watercolor notes in the artwork, reordering events and changing up the pacing, and good use of soundtrack make her romance with Mugi into a fully fledged romantic tragedy, one from which there's no straight answer, with no clear line between bad people and misguided friends, as both bring her pain all the same.

The following series are available for viewing NOW on Crunchyroll!

KONOSUBA -God's blessing on this wonderful world! 2

Masamune-kun's Revenge

Saga of Tanya the Evil

----

Ian Mertz is a graduate student in Toronto. He works in Computer Science though, so don't take his opinions on anime too seriously.

0 notes