#and its old copies were recorded as illuminated manuscripts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Manuscript Monday

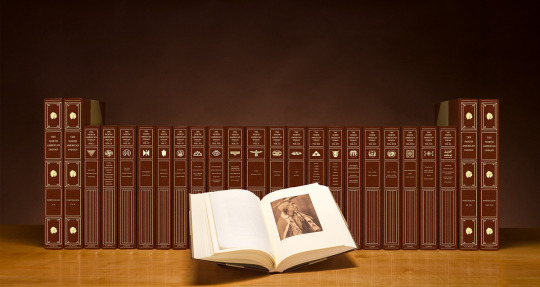

Shown here are pages from our facsimile of one of the most popular texts of the Middle Ages, Speculum Humanae Salvationis (The Mirror of Human Salvation). The text was written to expound upon the medieval idea of Biblical typology, or the ways in which the Old Testament of the Christian Bible foreshadows its New Testament. This type of book is part of the genre of speculum literature, which was made to record encyclopedic knowledge of a subject within a single book. The popularity of the Speculum led to it being copied many times, and hundreds of copies in several languages remain extant today from the medieval period.

Our facsimile, published in 1973 by the Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt in Graz, Austria in an edition of 72 copies, is from a 14th-cenury Latin manuscript housed in the Benedictine Kremsmünster Abbey Library in Germany, and catalogued as Codex Cremifanensis 243. It is one of the oldest copies of the Speculum.

The pages of the Speculum hold three Old Testament stories corresponding to one New Testament story, along with an astonishing 192 illuminations. While its subject matter is Biblical, we can see the everyday objects and clothing worn in the 14th century, since Biblical characters were dressed in contemporaneous clothing and architecture in the background is from the same period. This gives us an interesting insight into 14th century medieval culture by showing us the objects and places that surrounded these people in everyday life. Throughout the illuminations, some of the faces are smudged out with black ink; this shows viewers that these are the villains in the stories, though I have to say that in most cases, (especially where our poor friend is being sawed in half) it is pretty obvious.

View more manuscript posts.

View more Manuscript Monday posts.

– Sarah S., Former Special Collections Graduate Intern

#manuscript monday#manuscript facsimiles#illuminated manuscripts#manuscripts#latin manuscripts#Speculum Humanae Salvationis#speculum literature#typology#biblical typology#Codex Cremifanensis 243#Kremsmünster Abbey Library#Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt#Sarah S.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who created the manuscript?

NO. 1

Ever since the rise of modernism, it feels like people have only looked to see such medieval manuscripts in museums or hear about them in lecturers. The beginning of medieval, or illuminated manuscripts were beautiful but so very old and have to be handled with great care. Archaeologists and anthropologists have discovered and studied such manuscripts as a testament to keeping record of humanity’s past forms of writing. But would we ever get to such technological advancements, in forgetting our past, without it? This report explains the creation of how medieval manuscripts came to pass.

NO. 2

From the met museum, ‘Unlike the mass-produced books of our time, an illuminated manuscript is unique, handmade object. In its structure, layout, script, and decoration, every manuscript bears the signs of the unique set of processes and circumstances involved in its production, as it moved successively through the hands of the parchment maker, the scribe, and one or more decorators or illuminators.’’ Illuminated manuscripts began in Ireland after the fall of the western Roman empire. Christianity came to Ireland around 431 A.D, introduced by Palladius and reinforced by the ministry of a Roman Briton named Patricius, or St. Patrick as he’s called today. He was kidnapped at the age of sixteen, and spent six years in captivity before escaping back to Britain. Upon returning, he was met with ‘distrustful druids’, and ‘murderous bandits’, and by bribing tribal kings did he made it out alive.

NO. 3

Eventually, he came back to Ireland in the 5th century. The island became lidded with monasteries in the 6th, and in the 7th the scribes of these centers of religious life were experimenting with new forms of decoration and bookmaking, the better to reflect God’s glory in the written word.

The first illustrated book to be found by archaeologists was the Egyptian ‘Book of the Dead’, a guidebook for the afterlife in which those in question would come to face-to-face with the jackal headed god Anubis, where he would balance their heart against a feather to determine what would become of them. A fortunate soul would either be in the Elysian paradise, the ‘Field of Peace’, or travel the night sky with Ra in his sun-boat, or rule the underworld with Osiris; those less fortunate would be eaten by the chimera looking god Ammit the soul-eater, for her body was part crocodile, lion and hippo. From Keith Houston’s, The Book, ‘’One of the main reasons the Book of the Dead is so well studied is because so many copies have survived, their colorful illustrations intact for Egyptologists to pore over endlessly. And though their subject matter may have been a little monotonous, it is clear that the ancient Egyptians were past masters at the art of illustrating books.’’

NO. 4

Under Charlemagne’s the Great Holy Roman Empire, politics, religion and art flourished. Monks filled their libraries with tens to thousands of volumes, where they borrowed and copied books to expand their holdings and occasionally to sell to laypeople, and those who wrote and collected realized the importance of illustration was towards a society of illiterate people. The monks who were in charge of the survival of Europe’s history were very vocal about physical maladies and working conditions. The dismal chambers were called ‘scriptoria’ or the writing rooms, which was the most important features of a medieval monastery, other than the Church itself. But society within the empire was transformed. Skilled peasants were leaving their rural homes for towns and cities, while the cities themselves, such as Johannes Gutenberg’s hometown of Mainz fought to eke out some measure of independence from the old feudal aristocracy. Money was assuming a progressively larger role, and it spoke louder than an inherited title. Always a reflection of the societies that had made them, books were changing in response. Gutenberg’s printing press, which churned out books too rapidly for them to be illustrated by hand, is often blamed for killing off the illuminated manuscript.

1 note

·

View note

Text

List of 5 World's most expensive books

I have something a little bit different for you today. A mix of culture money and some world records you guessed it. I am talking about the world's most expensive books that have ever existed. For a book to be worth several millions of dollars. It needs to be written by a famous author. Who has a controversial or highly important subject and is a few hundred years old. Books get better and more expensive with age. I can’t pinpoint just one book that is the most important or relevant because there are so many. However, there are a few manuscripts that shaped our modern world. They are now worth quite a lot of money and can be found in the biggest and most important libraries. Precious Books:

The list that I do have today is indeed the most precious book history is kept safe and hopefully. Since some books are very old their state is quite fragile and the ink possibly fades out in some areas. That’s why it's so important to keep them in extremely good and safe conditions. So future generations will have a piece of history to look upon. Technology can help us preserve the book for years and years as a digital copy. But that takes away the whole feeling of a book. The texture and the smell holding a book in your hand. Flipping through the pages and making notes will always be the ultimate sensorial experience. Our children will probably not experience. IPads and Kindles are great tools for minimalist lovers’ digital nomads and our environment. But we have to admit that a physical book can be utterly luxurious and special. Let’s see which are the most expensive books in the world? Who are the proud authors and why they cost so much money? 1. Book of Mormon Joseph Smith 35 million $:

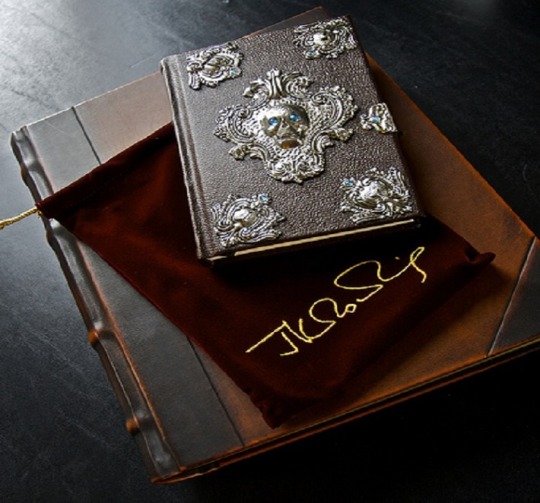

The first book on the list that I brought you the biggest and most expensive book that was ever sold. This book is highly controversial but even more than the book the religion it depicts and the people that follow it are believed to be a part of a secret world-leading organization. Although Mormons are viewed as the Illuminati of the modern world they actually believe in Jesus Christ and are much attached when it comes to this book. It was first published in 1830 and has been traveling quite a lot. Since then last year in 2017 the remaining manuscript was bought by the Church of Latter-day Saints for thirty-five million dollars. Making this book the most expensive they paid that much for the manuscript. Not because it's old or famous but because it's written by their founder Joseph Smith. He wrote the book after a revelation he had when he was 17 years old and with divine guidance. 2. Leonardo da Vinci Codex Leicester 30.8 million $

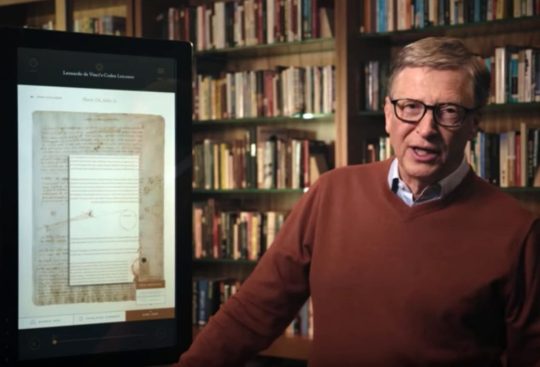

It was first named codex hammer but later changed with its first owner's name Thomas Koch Earl of leister who purchased it in 1719. Da Vinci was a genius and the manuscript is also one of his most desired papers. The codex provides a unique look into the brilliant mind of renowned Renaissance artist mastermind scientist and inventor. As well as an exceptional illustration of the link between art and science and the creativity of the scientific process as Leonardo thought of it. Handwritten with notes and observations the manuscript contains info regarding astronomy physics and chemistry all in Italian. The 18 pages folded in half and written on both sides were, in fact, one at an auction in New York City by another great mind in businessman Bill Gates. He bought it for thirty point eight million dollars. He was not the richest man just from Microsoft while he had the Codex. Bill scanned the pages and turned them into a screensaver and wallpapers for the Windows 95 Edition. 3. ST. Cuthbert Gospel 14.3 million $:

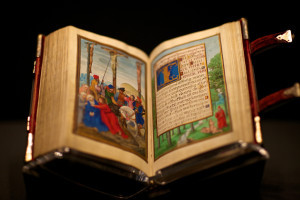

If the Gutenberg Bible was once one of the most important books ever printed there is one more religious piece on this list. The Holy Bible was written by the 12th disciples of Jesus and upon that some of them wrote other Gospels that were later discovered. Even Judas has written a gospel but the church does not recognize it nor the one written of Mary Magdalene. Dates back to the eighth century and is a small pocket size containing some parts of a notorious Gospel of John one of the most beloved disciples of Jesus. What makes this tiny book so expensive is the fact that it's the most well-capped book of its kind from that age and it's written in Latin. It has survived a lot of travels and Viking invasions and 1,500 years later it was bought by the British Library for fourteen point three million dollars and it will be on public display as of 2018. 4. Rothschild prayer book 13.4 million$: Moving on with a great book that belonged to an even greater family the Roth shield prayer book. It dates back from the late 15th century and it's full of amazing illuminated details on the sides of the pages. The opening pages show a beautiful Requiem Mass, a mass used for the dead. While the rest of the books 67 pages contain different illustrations made by the most renowned Renaissance Flemish artists.

The book is a masterpiece with splendid paintings and rich details which some say has great value for any art and history lover. Some of the famous illustrations depict Mary Magdalene of the famous prostitute that some say carried Jesus Christ's children. The book was stolen from Lewis Nathanael von Rath shield in 1938 and purchased later by an Australian businessman for thirteen point four million dollars. Which makes this manuscript the most expensive. John James Audubon the birds of America 11.5 million$: This time some subjects like biology or plants need good and realistic drawings. Where all the details can be seen and explained and since portable cameras were invented pretty late. Illustrations were the most accurate way of understanding and learning the birds of America by painter and naturalist John James Audubon. This is a collection of 435 hand-colored life-sized prints and includes a series of now-extinct species of birds from the US dating from 1827. There are only 119 complete copies known to the world and some of them were sold for millions of dollars. So far three of them were sold for 7.9 million dollars one for eight point eight million dollars and the last one for eleven point five million dollars. The drawings are so amazing and detailed they were even used for fabric painting in the UK. Conclusion: People who love history and books are also known for the value and importance of books. These are some of the world's most expensive books list. Later on, I will share another list of the rest of the expensive book. If is there any other books in your knowledge please share it in the comment box. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Southern and Central Europe, never quite effacing more classical styles in Italy. In the late 14th century, the sophisticated court style of International Gothic developed, which continued to evolve until the late 15th century. In many areas, especially Germany, Late Gothic art continued well into the 16th century, before being subsumed into Renaissance art. Primary media in the Gothic period included sculpture, panel painting, stained glass, fresco and illuminated manuscripts. The easily recognizable shifts in architecture from Romanesque to Gothic, and Gothic to Renaissance styles, are typically used to define the periods in art in all media, although in many ways figurative art developed at a different pace.

The earliest Gothic art was monumental sculpture, on the walls of Cathedrals and abbeys. Christian art was often typological in nature (see Medieval allegory), showing the stories of the New Testament and the Old Testament side by side. Saints’ lives were often depicted. Images of the Virgin Mary changed from the Byzantine iconic form to a more human and affectionate mother, cuddling her infant, swaying from her hip, and showing the refined manners of a well-born aristocratic courtly lady.

Secular art came into its own during this period with the rise of cities, foundation of universities, increase in trade, the establishment of a money-based economy and the creation of a bourgeois class who could afford to patronize the arts and commission works resulting in a proliferation of paintings and illuminated manuscripts. Increased literacy and a growing body of secular vernacular literature encouraged the representation of secular themes in art. With the growth of cities, trade guilds were formed and artists were often required to be members of a painters’ guild—as a result, because of better record keeping, more artists are known to us by name in this period than any previous; some artists were even so bold as to sign their names.

Gothic art emerged in Île-de-France, France, in the early 12th century at the Abbey Church of St Denis built by Abbot Suger. The style rapidly spread beyond its origins in architecture to sculpture, both monumental and personal in size, textile art, and painting, which took a variety of forms, including fresco, stained glass, the illuminated manuscript, and panel painting. Monastic orders, especially the Cistercians and the Carthusians, were important builders who disseminated the style and developed distinctive variants of it across Europe. Regional variations of architecture remained important, even when, by the late 14th century, a coherent universal style known as International Gothic had evolved, which continued until the late 15th century, and beyond in many areas.

Although there was far more secular Gothic art than is often thought today, as generally the survival rate of religious art has been better than for secular equivalents, a large proportion of the art produced in the period was religious, whether commissioned by the church or by the laity. Gothic art was often typological in nature, reflecting a belief that the events of the Old Testament pre-figured those of the New, and that this was indeed their main significance. Old and New Testament scenes were shown side by side in works like the Speculum Humanae Salvationis, and the decoration of churches. The Gothic period coincided with a great resurgence in Marian devotion, in which the visual arts played a major part. Images of the Virgin Mary developed from the Byzantine hieratic types, through the Coronation of the Virgin, to more human and intimate types, and cycles of the Life of the Virgin were very popular. Artists like Giotto, Fra Angelico and Pietro Lorenzetti in Italy, and Early Netherlandish painting, brought realism and a more natural humanity to art. Western artists, and their patrons, became much more confident in innovative iconography, and much more originality is seen, although copied formulae were still used by most artists.

Iconography was affected by changes in theology, with depictions of the Assumption of Mary gaining ground on the older Death of the Virgin, and in devotional practices such as the Devotio Moderna, which produced new treatments of Christ in subjects such as the Man of Sorrows, Pensive Christ and Pietà, which emphasized his human suffering and vulnerability, in a parallel movement to that in depictions of the Virgin. Even in Last Judgements Christ was now usually shown exposing his chest to show the wounds of his Passion. Saints were shown more frequently, and altarpieces showed saints relevant to the particular church or donor in attendance on a Crucifixion or enthroned Virgin and Child, or occupying the central space themselves (this usually for works designed for side-chapels). Over the period many ancient iconographical features that originated in New Testament apocrypha were gradually eliminated under clerical pressure, like the midwives at the Nativity, though others were too well-established, and considered harmless.

#gallery-0-5 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-5 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Gothic Art Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture.

0 notes

Quote

The ‘digitisation of everything’ explicitly threatens to supplant every single ‘old’ medium (anything carrying content in one way or another), while claiming to add new qualities, supposedly essential for the contemporary world: being mobile, searchable, editable, perhaps shareable. And indeed, all of the ‘old’ media have been radically transformed from their previous forms and modalities – as we have seen happen with records, radio and video. On the other hand, none of these media ever really disappeared; they ‘merely’ evolved and transformed, according to new technical and industrial requirements.

Alessandro Ludovico (Post-Digital Print, 15)

Much of what we read digitally attempts to emulate the visual and tactile experience of paper. I would argue that the digital world more closely replicates the experience of some of our earliest experiences with paper . Illuminated manuscripts of the medieval period were meant to be a sensory experience; sight, sound, touch and even smell. The manuscript demanded sensory engagement in order to glean all of it’s meaning. I think that digital world similarly asks its user to engage with it in a more sensory way. This would align with Ludovico’s assertion that media never disappears, rather, “evolve and transform.”

I suppose that I am more interested in the cultural connotations of a particular medium. Form affects content, and what if those forms have been specifically been designed for consumption? For example, the form of the novel - it’s length, format and para-textual elements - is designed to be sold and even encouraged to buy another. Ludovico gestures towards the supposedly more democratic desires of a contemporary world: the ability to edit, search and copy/paste any document seems like a more ‘open source’ form of textual engagement. These desires would seem to reflect our changing attitudes towards the authority of ‘the author,’ and published books more generally (things that we discussed last meeting).

While I agree with Ludovico that paper isn’t going anywhere, I think that the meaning of words like ‘intertextual’ will have their meanings negotiated. We don’t need to own or have read another book to understand an allusion or a reference.

Knowledge becoming more communal sounds good to me. That said, it might kill some of the simple fun of feeling like you are ‘in’ on the joke or reference of a text. You know, the part that makes you feel clever.

0 notes

Text

Appendix: the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Part 26: (1591) Intercalated First Month, Third Day, Midday.

86) The Same, Midday of the Third Day¹.

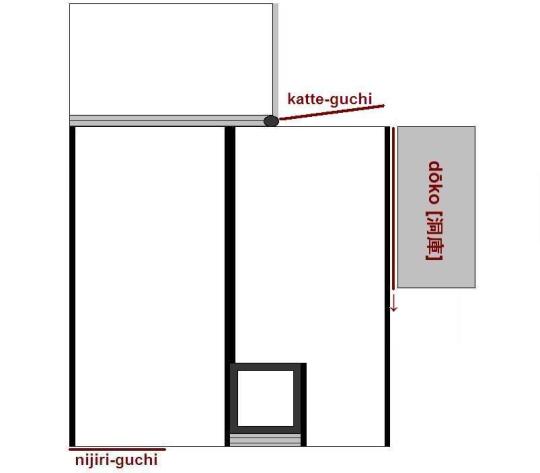

○ Two-mat room².

○ Itami-ya ・ Jōmu [伊丹屋・紹無]³, Kome-ya ・ Yojūrō [米屋・與十郎]⁴, the same ・ Dōtsū [同・道通]⁵, Mozu-ya ・ Sōan [もずや・宗安]⁶.

○ Chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小なつめ]⁷; ◦ Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ]⁸; ◦ Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡]⁹.

○ After tea was finished¹⁰: ◦ Kōrai-zutsu [かうらい筒], [with] plum blossoms [arranged] in it¹¹.

○ The feast was served in the large room¹².

○ Ko-tori senba-iri [小鳥せんば入]¹³; ◦ konowata [このわた]¹⁴; ◦ fukuto-jiru [ふくと汁]¹⁵; ◦ meshi [めし]¹⁶.

○ Kashi [菓子]: ◦ fu-no-yaki [ふのやき]¹⁷; ◦ yaki-mochi [���き餅]¹⁸.

_________________________

¹Onaji mikka no hiru [同三日之晝].

Onaji [同] refers to the month -- it is still the Intercalated First Month of Tenshō 19.

²Nijō shiki [二疊敷].

³Itami-ya ・ Jōmu [伊丹屋・紹無].

Itami-ya Jōmu [伊丹屋・紹無], who was also known as Shin-ho-an Jōmu [心甫庵 紹無], was a chajin from Sakai.

The Itami-ya [伊丹屋] house later became prominent after the rise of kabuki [歌舞伎] in the Edo period -- though it is possible that they were already associated with the performing arts (perhaps Nō [能]*, in which Hideyoshi also had a great interest) during this period. ___________ *Since the Ashikaga period, Nō [能] interpretations had frequently been more energetic than what came to be preferred later (in the Edo period). In a very real sense, Kabuki arose out of this more active form of the performance art, while leaving the classical (and sedate) themes to the -- by then -- archaic Nō.

That other famed nō actor of this period, Miyaō Saburō Sannyū [宮王三郎三入; ? ~ 1582] -- who fathered the line that became the "officially recognized" Sen family not long before Hideyoshi's own death -- was also an intimate of Hideyoshi (and, indeed, it was Sannyū's self-sacrifice at the battle of Yamazaki, where he literally intercepeted a bullet that had been aimed at Hideyoshi, which earned him and his son the undying thanks that permitted Hideyoshi to reinstate the Sen family name, under Sannyū's son Shōan, several years after Rikyū's death in ignominy).

⁴Kome-ya ・ Yojūrō [米屋・與十郎].

A wealthy machi-shū based in Kyōto* (the Kome-ya firm was involved in the rice trade – which apparently included the exchange of the samurai’s rice stipends for cash), the details of whose life have been lost.

Yojūrō was mentioned earlier in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, as a guest at the ato-mi that followed Rikyū's morning chakai on the 11th day of the Twelfth Month of Tenshō 18. ___________ *Apparently in the Shimo-gyō [下京] part of the city near Shichi-jō [七条] (Seventh Avenue).

The block where the firm was located is still known as Komeya-machi [米屋町].

⁵Onaji ・ Dōtsū [同・道通].

Onaji [同] here refers to the yagō [屋號]: in other words, Dōtsū was also a member of the Kome-ya house -- perhaps Yojūrō's brother or cousin; but nothing is actually known about him*. ___________ *There was a man from a military family who lived during this period named Inaba Michitō [稲葉道通; 1570 ~ 1608] (Michitō [道通] is another way to read the name Dōtsū [道通]). He was a daimyō and nobleman (junior grade of the Fifth Rank), who served as an imperial chamberlain of the left division (sakon no kurōdo [左近蔵人]). But given the person's position during the chakai (third guest), and the status of his fellow guests (all machi-shū), it does not seem that this individual can be identified with Michitō.

⁶Mozu-ya ・ Sōan [もずや・宗安].

Mozu-ya Sōan [萬代屋・宗安; ? ~ 1594] was one of Rikyū’s lifelong friends (they were perhaps of a similar age, though the details of Sōan's early life seem to have been lost), as well as the husband of one of Rikyū’s daughters. He was also numbered among the tea masters from Sakai who was employed in an official capacity in the tea department at Juraku-tei, and enjoyed a good reputation in chanoyu among his contemporaries.

⁷Chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小なつめ].

The use of this tea container “says” that the tea served during this chakai was ground specifically for this gathering* (rather than being left over from the morning chakai).

The natsume would have been tied in a shifuku.

Rikyū appears to have abbreviated his record of this chakai†, since other utensils would have been needed to serve tea to his guests. Surely, the rest of the tori-awase would have been the same things that he used at the morning gathering that preceded this one:

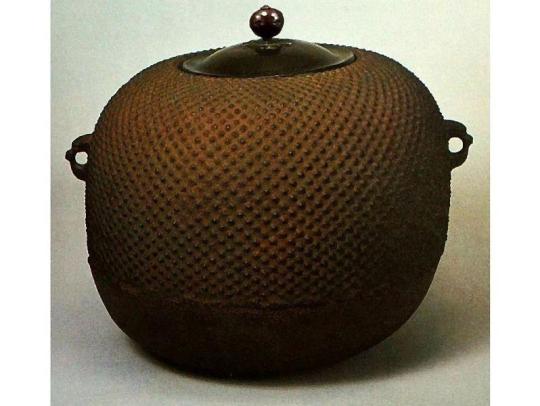

◦ arare-gama [霰釜];

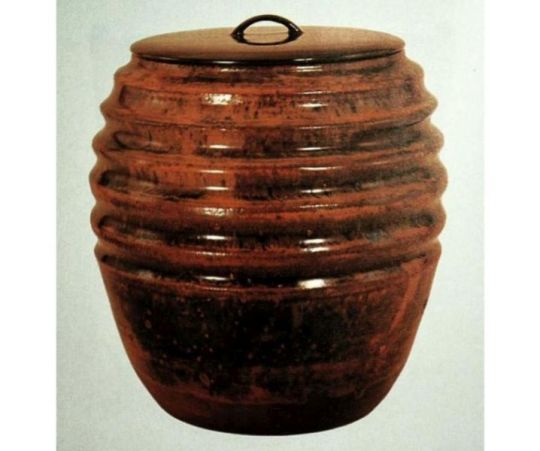

◦ Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水指];

◦ Ko-mamori chawan [木守茶碗];

◦ ori-tame [折撓];

◦ take-wa [竹輪];

◦ hirai Shigaraki mizu-koboshi [平い信樂水飜]‡.

__________ *In other words, Rikyū ground the tea after the first chakai was over, the ko-natsume indicating that this was all the tea he was able to grind in the time between the end of the morning gathering and the end of the naka-dachi for the midday gathering.

†Suggesting that he was pressed for time. Perhaps this group of machi-shū had some reason to confer with Rikyū (certainly as the date for Hideyoshi’s upcoming invasion of the continent approached, the business community -- which provided much of the financing for the venture -- would have been concerned about updates) would have, and asked to meet him on the spur of the moment. Rikyū would have been one of the main intermediaries between the Sakai- and Kyōto-based machi-shū and Hideyoshi’s court at Juraku-tei.

‡It is also possible that he used a mentsū [面桶] as the koboshi, in the interests of purity.

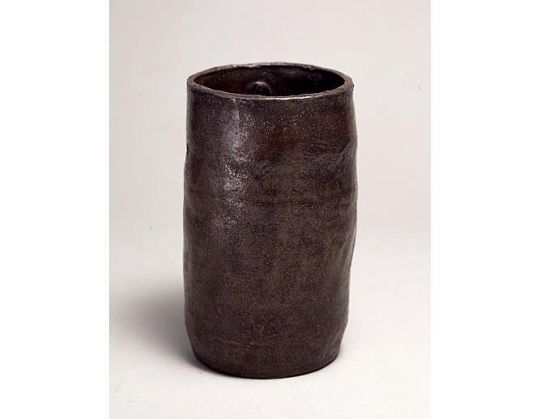

⁸Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ].

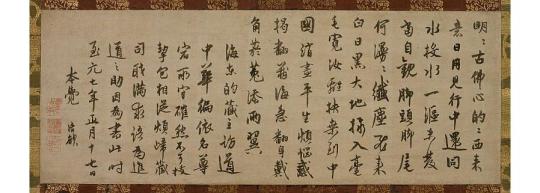

⁹Yoku-ryō-an bokuseki [欲了庵墨跡].

¹⁰Cha sugite [茶すぎて].

Cha sugite [茶過ぎて] means “after the [service of] tea had been concluded.”

Precisely why Rikyū may have opted to wait to arrange the flowers until a point near the end of the chakai is not clear. Perhaps the sentence is a mistake? (In other words, perhaps Rikyū intended to indicate that the hanaire was added to the scroll -- suspended on the outer-wall-side pillar, and either miswrote or his words were not transcribed accurately. See footnote 12, below, for another indication that there may have been problems with this entry.)

¹¹Kōrai-zutsu ・ baika ireru [かうらい筒・梅花入].

The Kōrai-zutsu [高麗筒] was a kake-hanaire [掛け花入]. It seems that Rikyū may have suspended it on the pillar, while leaving the scroll hanging as it was.

Contrary to modern practices, if a kake-hanaire was not suspended on the wall at the back of the toko, it was hung on the minor pillar in the outer wall side of the toko (whether hung on the pillar, or on the bokuseki-mado as Furuta Sōshitsu did*, the idea was to suggest that the flower was growing outside in the garden, and simply leaning into the room: the flower always should arch toward the temae-za, regardless of where it is found).

Hanging the hanaire on the toko-bashira is a mistaken interpretation of the purpose of the hook that was sometimes (usually temporarily) nailed into that pillar at night gatherings: this hook was used to hang an oil lamp in the old days, the purpose of which was to illuminate the signature and name-seal(s) on the kake-mono (according to the classical teachings, the toko-bashira should always be located on the side of the scroll where the signature/seals appear). This hook was never used for the flower vase; and, indeed, it was usually removed completely after the gathering (since its position depended on the scroll -- if the host hung a different scroll at a subsequent night gathering, the location of the flame would have to be adjusted higher or lower accordingly). Unfortunately, the machi-shū did not understand this point, and, fearful of doing something wrong, they left the hook where the previous tea master had nailed it; and then conflated this hook with the other temporary hook that was sometimes nailed into the minor pillar (for the hanaire). The result is that, if the flowers are hung on the toko-bashira, it is impossible for them to have the correct orientation (leaning toward the temae-za). ___________ *Rikyū’s bokuseki-mado was usually located outside of the toko, behind the shōkyaku’s seat, making it impossible for him to hang the hanaire there. Suspending it on the minor pillar was equivalent to Oribe’s use of the bokuseki-mado for this purpose.

¹²Furu-mai hiroma ni te [振舞廣間にて].

Furu-mai [振舞] means a “feast” (i.e., a rather elaborate meal, served with some ceremony).

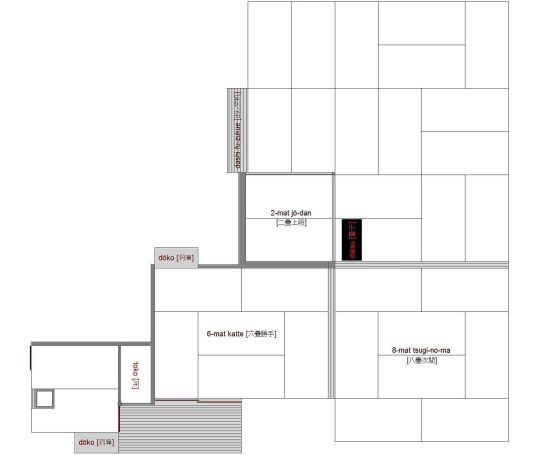

“In the large room” refers to Rikyū's 18-mat “Colored Shoin” -- which adjoined the 2-mat room through the 6-mat katte and 8-mat tsugi-no-ma [次の間] (as shown in the above sketch.

This statement, the language of which is rather odd (and atypical of Rikyū’s known usages) is not found in the Hisada family’s version of the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki. Since it was not usual for people making copies to add anything to the text, this suggests that this section of Rikyū‘s manuscript may have been in a poor state of preservation, or else Rikyū wrote something and then scratched it out (and the statement furu-mai hiroma ni te was someone’s guess at what had been written). Perhaps Rikyū was writing this entry quickly and his dyslexia was interfering with his concentration.

¹³Ko-tori senba-iri [小鳥せんば入].

Ko-tori [小鳥] is a general name for the sparrows and small finches that were commonly taken by the hawkers during the winter months.

Senba-iri [船場煎り] is a style of cooking that was popularized by the food stalls that lined the wharves of Sakai: small birds (fowl that, because of their size, can be cooked relatively quickly) prepared for roasting were tied to skewers and suspended above a wooden fire while being basted with a mixture of sesame oil, soy sauce, sake, mirin, and crushed garlic.

¹⁴Konowata [このわた].

The salted entrails (primarily the gonads and their contents) of the sea cucumber -- a relative of the starfish and sea urchins.

¹⁵Fukuto-jiru [ふくと汁].

A clear soup (almost a stew) made from the fugu [河豚] -- in English, puffer fish (also known as the blowfish, or globefish). The prepared fish were chopped into pieces and boiled with pieces of daikon and crushed garlic. Freshly chopped leeks were sprinkled on top of the soup before it was served.

Modern-day fugu chiri-nabe [河豚ちり鍋] (also simply called fugu chiri [河豚ちり]) is very similar to what Rikyū here calls fukuto-jiru [河豚頭汁].

¹⁶Meshi [めし].

Steamed rice.

¹⁷Fu-no-yaki [ふのやき].

Rikyū’s wheat-flour crêpes, spread with sweet white miso (or “miso-an” [味噌餡] -- white bean-paste flavored and sweetened with white miso rather than sugar or honey) before being folded into bite-sized pieces.

¹⁸Yaki-mochi [やき餅].

Mochi [餅] (a dried paste made by beating sticky-rice in a wooden morter until smooth, and the forming this into cakes that are dried; the cakes are sliced into small pieces before being served) that has been toasted on bamboo skewers over a charcoal fire (to soften it). While this dish was commonly wrapped in nori [海苔] (paper-thin sheets of dried laver) during the Edo period, it seems that during Rikyū’s period it was simply served on the skewer (to facilitate handling of the potentially sticky piece of mochi).

It is important to note that the Hisada-bon has yaki-guri [やきくり] here, rather than yaki-mochi., which suggests that the entry was written in haste, and perhaps carelessly. Yaki-guri [焼栗] is roasted chestnuts -- another of the kashi frequently offered to his guests by Rikyū, and the one most often paired with his fu-no-yaki [麩の焼].

0 notes

Text

Overlooked Texts, Overlooked Images (Part I): An Erasmian Album

Fifty-two discoveries from the BiblioPhilly project, No. 40/52

Album of Engravings and Devotional Texts by Erasmus, Marco Girolamo Vida, and Prudentius, Philadelphia, Free Library of Philadelphia, Lewis E 179, fols. 46v–47r, Erasmus of Rotterdam, Prayer for Seious Illness; engraving, Christ breaking bread with the Apostles

Sixteenth-century books that combine manuscript text with engraved or woodcut images can sometimes fall through the cracks of scholarship. On account of their hybrid character, they are often neglected by manuscript specialists in favor of entirely hand-written books. At the same time, scholars of early printing, on the lookout for editions by recognizable publishers, tend to cast aside these complex combined works in the search for more easily classifiable items. However, over the past several decades these tendencies have started to change. Increasingly, scholars have taken on the complex interface of early printing and handwriting as a fascinating subject in and of itself.1

Still, the story of one neglected item, preserved in the collections of the Free Library of Philadelphia, perfectly illustrates the disciplinary pitfalls described above. Lewis E 179 is a modest book of 109 paper folios written in a non-professional, Northern European humanist hand, adorned with forty-five engravings illustrating the Life of Christ from the Annunciation through to the Last Judgment. Based on the texts and images, the book could be dated as early as the 1530s. However, the distinctive watermark visible on some of the book’s pages (with the help of transmitted light) was employed only in the 1550s and 1560s, in the Netherlands and Northeastern France.2 It provides a relatively late terminus post quem and a rough localization for the book’s place of origin.

Lewis E 179, fol. 35r (detail of watermark visible with the aid of a light sheet); drawing of Briquet 9373 watermark from Briquet Online database

Evidence of subsequent provenance places the book in some important German collections of the early modern period. An early bookplate on verso of first flyleaf dated to 1661 indicates that the book was formerly in the possession of Joachim Enzmiler, Count of Windhag,3 while a second bookplate, from the eighteenth century, records the ownership of Eberhard von Kniestedt. Before joining the Lewis Collection, the book had been in the possession of the great German-Spanish-English bibliophile Henry Huth (1815–1878), who famously preferred intact and pristine copies to damaged books, qualifying the latter rather uncharitably as “the lepers of a library.” Huth spent a considerable amount of time in Hamburg, which may have provided him with access to this item. In both the posthumous 1880 catalogue of Huth’s collection, written by his son Alfred Henry Huth, as well as the 1911 catalogue of Alfred Henry’s collection, the book was described principally by means of its engravings.4

Lewis E 179, flyleaf 1 verso, bookplate, Joachim Baron Windhag 1661; inside front cover, bookplate, Eberhard von Kniestedt

Since its acquisition by Lewis, the book had been summarily described in only two places: the catalogue of Lewis’ western manuscripts published by Wolf in 1937, and the de Ricci census.5 John Frederick Lewis, the Philadelphia bibliophile who had a penchant for oddities that could help illustrate the history of writing, evidently was not taken in by the widespread disinterest in this sort of book, even if those who catalogued his collection after his death did. Lewis liked “multimedia,” creations—he grangerized (adorned with extraneous material) dozens of his own modern reference books with pasted-down snippets and even full pages drawn from illuminated manuscripts. Lewis probably appreciated the book for its unusual amalgamation of print and script, not to mention its interesting original leather binding, with, on each side, a stamped center panel showing Christ triumphing over Death, with the initials HGV—perhaps those of the binder—, all set within blind-tooled, all’antica borders of scrollwork and portrait medallions.

Lewis E 179, front cover; back cover

Looking more closely at the composition of Lewis E 179’s texts as part of the BiblioPhilly cataloguing process, I discovered that these consist of prayers and other devotional works by two important intellectual figures of the first half of the sixteenth century: Desiderius Erasmus and Marco Girolamo Vida. Interspersed as well are excerpts from the late-antique Christian apologist, Prudentius. These passages were copied by hand from editions that had been produced recently.

The prayers authored by Erasmus that have been copied into this book stem from three major sources. Eleven votive prayers are drawn from his Precationes aliquot novae, first published in 1535. These are interspersed throughout the work, diverging from their order in the 1535 edition. They consist of votive prayers for Receiving Communion, for Docility, for Penance, Against Temptation, for Thanksgiving in Victory, for Serious Illness, as well as prayers to the Virgin, to each of the three persons of the Trinity, and to Jesus as the son of the Virgin. Seven sections found in the second half of the book stem from Erasmus’ Precatio Dominica, a short work of seven prayers for the days of the week based on the seven parts of the Lord’s Prayer, first published by Froben in 1523. 6This work became immensely popular throughout Northern Europe and beyond, and within five years had been translated into German, English, Czech, and Spanish. Six sections, concentrated in the first half of the book, are excerpts from Erasmus’ paraphrases of Luke, Matthew, and John, each of which was published separately in the early 1520s.

Intercalated within the first half of the book are sections from the Christiad and four extracts from Prudentius’s Liber Cathemerion. The former is an epic poem first published in 1535 but written at the request of Leo X, which provides a Christian counterpart to Virgil’s Aeneid.7Its author, Girolamo Vida (ca. 1485–1566) was an Italian humanist, bishop, and celebrated poet during the early Counter-Reformation period.8 Works by the early Christian poet Prudentius, here represented by hymns for Epiphany, the feast of the Holy Innocents, for before meals, and for after meals, were appreciated by Erasmian humanists for their conflation of classical Latin forms with Christian motifs.9

There are other surviving manuscript compendia that contain assortments of Erasmus’ prayers, such as an unillustrated manual today in Brussels (Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, MS 5010).10 However, on the whole, such items remain understudied, not to mention un-digitized. Hopefully, the substantial community of Erasmus specialists will now be able to discover the intriguing Philadelphia volume and provide yet more information regarding its original context.

By pairing a unique selection of manuscript texts with an unusually extensive cycle of printed images, Lewis E 179 provides first-hand evidence for how these popular devotional texts were adapted and recombined by readers as the popularity of the traditional Book of Hours waned. The Prayer Book demonstrates how a new type of devotional manual could provide an idiosyncratic alternative to traditional forms in a period of religious foment. But what of the forty-five engravings that punctuate its pages, which remain unidentified? More will be said about those next week, when we will be joined by guest contributor Dr. Brooks Rich, Associate Curator of Old Master Prints at the National Gallery of Art and recent University of Pennsylvania graduate.

from WordPress http://bibliophilly.pacscl.org/overlooked-texts-overlooked-images-part-i-an-erasmian-album/

11 notes

·

View notes