#and i just kind of massacred it here in order for the background chants to match up w the gang looking up at the fate strings

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

tumblr

tlovm opening x your turn to roll (hd)

#the legend of vox machina#tlovm#critical role#vox machina#cr#cr1#my edits#not tagging everything because i'm like 85% sure someone's done this before so im not going to embarrass myself too hard#stuff im proud of in this edit: 'dm to guide you' over keyleth facing that one monster#the beat on 'about to be dead' right as pike and grog start killing#'monster incoming' / 'inspiration is waiting' over percy in jail/percy and orthax#stuff im NOT proud of in this edit: the 'take a chance roll the dice' part of the m9 intro w beau and yasha is SO sexy#and i just kind of massacred it here in order for the background chants to match up w the gang looking up at the fate strings#you win some you lose some

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I just finished VHS and I absolutely loved it. One of the shorts was a bit lacking to me, but even that one was enjoyable to watch. The only big criticism I have is that like at least half the shorts showed a lot of unnecessary tiddy (the only one that didn’t feel totally unnecessary was the one where the whole plot is dudes tryin to make porn) but I mean it’s found footage and I get that irl people do show off to each other on video calls and yknow,, porn. So I can let it slide but I’m not gonna enjoy it lol. Also this goes for most found footage I’ve seen, but sometimes it’s really hard to make out who’s who and what’s going on. But overall it was really good.

There were a few comments (I watched it on shudder lol) calling the movie misogynistic, which I don’t get? I mean unless they were talking about the tiddy issue, but even that I don’t think was meant to be framed as a good thing.

Like the movie is 5 shorts in between breaks of an ongoing story of some dudes breaking into a house. They’re trying to steal some tapes, and what’s on them is the bunch of shorts we’re shown. So the overarching story of the guys in the house has nothing to do with women, except one scene where they gang up on and try to strip a woman in a parking lot, which I’m pretty sure is clearly meant to be a bad thing? I mean throughout the movie we’re shown that these guys are assholes (filming harassment of women for money, excessively saying slurs, breaking into a house for more tapes that could get them money). Yeah the characters are misogynistic from what we can tell, but that doesn’t mean the movie or director is condoning their actions.

Ok onto the actual shorts (I don’t know what any were called but I’m pretty sure theyre all in order in my head lol). I want to pick out whether the individual shorts were misogynistic at all (because I have literally nothing else to do) so for that I might have to spoil. Any spoilers will be crossed out so they’re at least a bit harder to read. And like, I’m no expert in feminism (I don’t consider myself one, but I’m not exactly anti either) but being a person with a brain and opinions I’m going to talk about it.

1: This was the only one I had any previous knowledge of going in, and I was absolutely terrified of watching this whole movie because of the jumpscare and bits of creepiness I’d seen lol. So it’s about this group of guys who are trying to make some porn, so they pick up some girls, take them clubbing, and then go to a hotel to smash. Without spoilers, one of the girls acts really really friccin creepy and I think this one scared me the most overall, even knowing the basics of what would happen. Honestly I’m surprised the internet hasn’t turned her into a meme or waifu like some people did with Momo lol. I for one really want to draw her now (but also I’m terrified of looking up reference photos 👊😔). I think I read that they made a full movie-length version of this story but I could be wrong.

Spoilers: So what happens is this creepy girl is some kind of monster who lures men in to have sex with her, so she can eat them and rip their dicks off and all that fun shit. So like a siren, but on land? Honestly I don’t even know if it’s accurate to say she lures them in, because she really didn’t do anything, the guys kinda just found her and decided to use her? Also I think she had wings?? But again, handheld camera, hard to see everything. I think that what makes this one is that while she is creepy, she doesn’t really seem dangerous, or even like she wants to be there at all. Like when the guys give her and another girl drugs, the other girl seems ok with it, but it seemed to bother the creepy girl a bit. She had this innocent vibe to her that just makes her even more creepy. And then it’s even more shocking when she starts eating these bois. So yeah I don’t think this one was misogynistic at all. The male characters just wanted to exploit her and profit from her body, and she didn’t say no but she didn’t say yes either, which is pretty interesting to see. It’s not like she tricked the guys because she never actually consented to sex. All I remember her saying was “I like you” a few times. 10/10 we love a lady who eats her attempted rapists.

2: This is the one I wasn’t entirely satisfied with, but it was very good and enjoyable nonetheless. It’s about this couple on a road trip in,, I wanna say Arizona? I’m Canadian, I’ve never heard of a state in my life. So anyway they’re at a hotel in the middle of the desert, there are a few parts that were pretty creepy but didn’t actually mean anything in the story, like there was this fortune telling machine that I thought would be something supernatural, and a scene where they’re climbing around a canyon which was just generally anxiety inducing lol. But what the story is actually about is that someone is stalking them. This one I can discuss the misogyny levels without spoilers. There’s one bit where the guy is trying to get the girl to take off her shirt, and she says only if you turn the camera off. Which he doesn’t, and after a little argument he finally accepts the no. So like, dick move, but only a tiny part of the story.

Spoilers: there are some creepy scenes of the stalker recording them both while they sleep, and stealing their money and stuff, and then later stabs the guy in the neck. But then it’s revealed that the stalker is actually two people and they film themselves making out in the bathroom mirror. I couldn’t tell if it was a guy/girl or two girls, and since it was that hard to see their faces it just occurred to me that one of them might’ve actually been the gf? Like we didn’t see what happens to her after, and it’d definitely be a more satisfying ending for her to have betrayed her bf and not just some rando stalkers. Hm. Still unclear but good.

3: This one was really fun, it’s these 4 college aged friends who take a trip to the woods, it’s pretty tropey like cabin in the woods, there’s the final girl, the slut, the nerd, and the popular jockish dude. Which I’m pretty sure was on purpose since it’s kind of a slasher. Otherwise I’d be a bit more critical of the ‘slut’ character who Literally Never Shuts Up About Sex in this short lol. But I think that was meant to be a comedic choice. Idk. Other than that, no issue. So basically final girl has kinda organized this whole trip but she starts acting weird and saying creepy stuff about things that had happened in the forest. This one really felt like a creepypasta, but like the best kind. I really love what they did with the bad guy. I really don’t want to spoil this one, so don’t read the spoilers unless you’re sure you’ll never watch it. It’s great.

Spoilers: So the twist is that final girl had been here before with her friends and was the only survivor of a massacre by some monster in the woods. So now by taking these new people on the trip she’s trying to lure the monster out using them as bait, because nobody believed her after the last trip when she told people it wasn’t human. So we get a bunch of cool deaths, and that sweet sweet betrayal. I was kinda surprised by how much they lingered on some of the gore but that’s not really an issue for me. It did suck to see the main girl die, but I mean it’s found footage not ‘I killed a monster and totally got away, here watch’ footage.

4: This one was actually really cool in terms of like ~feminism~ or whatever. I mean it doesn’t even have to be read as some kind of feminist theme, but that was just the vibe I got. I really don’t think I can go into detail on those themes without spoilers, but the basic premise is that this girl is video chatting her bf (who’s away for school or something) and she’s worried that there are ghosts in her apartment. There’s a neat backstory about something similar happening to her when the guy was away during her childhood, like weird bruises and other injuries she doesn’t remember, so it definitely keeps you interested. Also another one I reeeally don’t want to spoil because the twist is so cool.

Spoilers: So the truth is the guy actually was nearby the whole time (possibly in her place because he rushes in the room pretty quickly when she’s attacked), and it turns out that it’s not ghosts, but aliens, and the bf is using the gf to put trackers and alien babies in her, and tricking her into thinking she just got in some weird accident and forgot, which leads her to get misdiagnosed with something like schizophrenia. I mean it’s a perfect metaphor for gaslighting (he’s not hurting me, I’m just crazy), and while that’s not an exclusively feminist theme by any means (both genders are capable of abuse, and both genders are capable of being victims!) it being a theme here shows that this short is absolutely not misogynistic at all. Honestly I’m surprised I haven’t seen more people talk about this one. It’s really really great in terms of the plot, twists, and underlying themes my dumb brain came up with.

5: This one is really really cool, at first I was a little bored with it, but then you’re kinda like hm what’s going on, and then you’re like oh okay that’s going on. Coolcoolcool. So basically these 4 dudes are going to a Halloween party and they’re kinda lost, and they end up at this huge house, so they go in and it’s empty but really big and creepy so they’re like ‘maybe we’re early, or it’s more of a haunted house than a party’ stuff like that, so a bit of it is just the guys exploring the house and vaguely creepy stuff happening in the background. I’m just gonna leave it at that because like, it’s not exactly a twist but it is really unexpected.

Spoilers: So they hear people talking upstairs in the attic and they’re like ‘o nice we found the party’ but no it’s a literal cult chanting and beating up this girl they have tied up. The cult leader is like ‘wtf get outta here’ and the guys kinda get chased away, but one dumbass just had to be like ‘no man we gotta save her’ (king tbh. ur sacrifice will be remembered) so they all go back up there, beat up the cult guys, and get the girl out of there. But that’s when the really creepy stuff happens in the house, like dishes throw themselves at the guys and arms reach out of the walls (I’d actually seen this bit before in a try not to be scared compilation, but I didn’t know what it was from lol) but they do get out and into their car. But then the girl just disappears and the car stops working, and then they see her out the window and she looks kinda demony, and oop their car is stopped on a train track aaa. This one I’m kinda torn on, like about the misogyny thing, because yeah having the only female in the cast being a demon and justifying the cult’s treatment of her is iffy, but at the same time...dude she’s literally a demon, I’d be chaining her up too lol. So yeah I’m definitely leaning toward the not misogynistic side.

Overall I don’t see this movie as that misogynistic at all, and it’s otherwise just a really really good time. Definitely recommend.

0 notes

Text

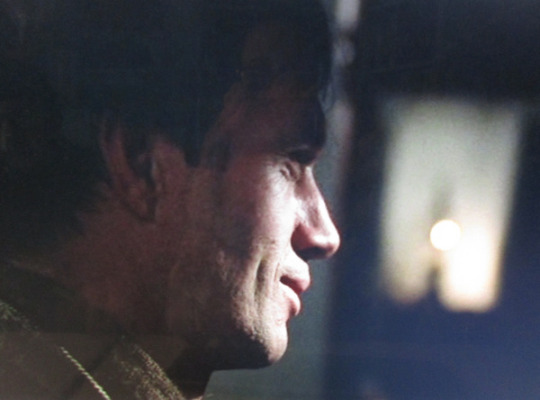

INGMAR BERGMAN’S ‘THE SERPENT’S EGG’ “You’ve been thinking much too much, lately…”

© 2019 by James Clark

The films of Ingmar Bergman are all of a piece. They endeavor, from many angles, to make sense of the powers that be. This concern is particularly pressing in regard to the work today, namely, The Serpent’s Egg (1977). On the basis of many vicissitudes of Bergman’s history at that production, a whole industry arose, of delighting in what seemed to have been a weakening of confidence—on the very flimsy basis of punitively catching Bergman straying from his vigorous roots. Were the wags to have troubled themselves to comprehend those roots (well disclosed), they would have dropped that childish game and got down to business.

At the risk of belaboring the obvious, we must turn to recognize our guide’s commitment to taking on a field of very complex physicality. At the outset of his career—in the film, Sawdust and Tinsel (1953), with the figure of Alma and her brief but impressive ecstatic balance; and in the film, The Seventh Seal (1957), with Jof and Marie, and their child hopefully one day excelling in acrobatics and juggling—we have an invitation to a party of unending carnal delivery.

If you think that tax problems; turning away from a homeland to resettle in Germany; and linking with a Hollywood bagman (Dino De Laurentiis [in fact, at that time, only recently based in the USA]; and with involvement in La Strada, Nights of Cabira, and Blue Velvet] could destabilize the resolve of Bergman’s interests, you don’t know what this priority entails. Moreover, there was cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, still in place and game for risking new visuals with unusually big bucks.)

Relocating to Munich, he would have been strongly reminded of his frequent (though unspoken as such) engagement with fascism, that simplistic and often murderous keening for absolute, homogeneous gratifications. To date, his most probing construct of the phenomenon of such arrested, facile obsession resided in his film, The Passion of Anna (1969). There, in a remote, rural corner of the already remote Sweden, a woman, namely Anna, manages to spearhead a one-person massacre on the pretext that her supposed entitlement to having things entirely her pedantic and dim way has gone awry. Though very clever, her scheme could not have reached its successes without the complicity of a muddled artisan/ farmer, namely, Andreas. With the windfall from Los Angeles, Bergman would seize the moment to revisit the serpent that was Anna. But this time Anna would be a jackboot mob, while a Saint Anna Clinic would oversee the early phase of a tinkering of wanton, sadistic “experimentation” with human subjects. Another muddled artist, namely, Abel (and you know, sort of, where that’s going), teams up with his widowed sister-in-law; and urban decadence replaces the hot-house sophistication of Anna’s hosts, Elis and Eva, in the country. It is the Eva-moment here, namely, Manuela, who, along with Abel, make The Serpent’s Egg a thrilling study of large-scale cowardice and small-scale love.

Although there will be here the usual dazzling theatrical-dramatic display in order to convey the corridors of problematics—including a number of failing oracles— this film (quick to exploit the financial heft) becomes more a filmic tone-poem than dramaturgy. Therefore, I want to start out (the vehicle’s venue being chilly Berlin, in 1923) with the panoply of woolen apparel. One of Anna’s cheap coups was slashing up a flock of disinterested—thereby superior to her—sheep. And that bloodbath becomes a visceral presence as to savoring a unique progress amidst protracted distemper. In mythology, Abel was a shepherd. In cinematography, Abel, a bit of a fashion-plate with his two-toned dancing shoes (seemingly ready to star on Broadway or in Hollywood), sports a cute woolen fedora which, were you to concentrate solely on it, might make one believe that he is quite alive. (To complete the effect, while disregarding his face, he wears a dark tan woolen jacket over a light tan woolen shirt. His woolen scarf is black. His woolen pants correspond to the rest of the ensemble to complete an impression of careful selection and taste.) Just before we first meet him, there is the film’s opening scene of a throng of Berliners moving toward us in slow-motion—also in woolens, with some of the women’s cloche hats resembling sheep heads—and resembling a push to market. The murky, black and white cinematography there (with the film actually in color) elicits a venerable state of affairs; and beyond that, there is the perpetual gloom upon Abel’s visage, and his veering body language. He looks up Manuela (a risqué dancer at a cabaret; but more than that), with news that his brother—once being a member with the other two in a circus act, and such a pain in the ass she had to dump him—had shot the so-called, “Max,” through his throat depositing his brains all over the back of his bed. The show had to go on after her departure; but a career-ending accident to the Caine left the boys in a crisis—softy Abel losing his nerve to start afresh upon major creation. Abel might be a write-off. But, bright as a button, Manuela, has found a gig that works for her. Though the patrons would not know about it—and perhaps even would prefer something more predictable—she (true to the mystery of her trapeze practice) has migrated to that shock and awe known as German Expressionist dance (Neuer Tanz), where body action gets uncanny. That night, bedecked in curly green sheep hair, she splays her legs and, pounding out some Germanic chant, becomes a possessed puppet or doll, a seductive siren, or a creature crying out during a slaughter. Abel, the former risk-taker and maven of alternate sublime, scowls and, as he no doubt found very early at his family mansion, adopts a hard line toward the great unwashed. Max (the elevated) and Abel (the sweet) had, no doubt, an early spree of rebellion (always mindful of a generous safety net, but going on to dispense with it from out of their pitiful Bohemian pride).

Getting to the bottom of this crisis of mood will have been assisted by two other figures—his dare-devil, former boss, from a past at that mixed fun-time; and the Chief of Police, drawing from the “survivor” particulars about the actions of two English speakers, lacking German (and one, Manuela, European of unknown background) in the crash of post-World War I Germany. He tells the cop and us, “I was born in Philadelphia [the liberty town]. My folks come from Riga, in Latvia. The three of us came to Berlin” [after Max’s accident]. Back, close to the stage where Manuela is doing pretty well, someone addresses the guy expensively dressed, not doing well at all, “Did we smoke our first cigarette together? Amalfi, 26 years ago. Our cottages were next door to each other. Rebecca, right?” Abel rudely rushes away. But his Eurotrash, overstuffed appetites don’t get lost.

Going back to the film’s beginning can better establish the pitch of that (spent) force. Coming home at dark, staggering from a chronic drunkenness, he almost relishes the horribleness of his shabby existence. “A pack of cigarettes costs 400 billion Marks, and almost everybody has lost faith in both the future and the present…” Overheated, melodramatic gestures like that—extending to the work’s title—saturate the dimensions of the double protagonists. Entering what the brothers have been able to afford (and perhaps the mainspring of the suicide by the only employable sibling), Abel pauses at the foyer where a large room accommodates a dinner/ prayer meeting. At the open doorway, there is a panel of geometric, mutedly colored décor, rather closely resembling the stained-glass windows of Andreas, whose fecklessness is no match for a filthy brute like Anna. Abel is arrested by the warm and gentle union, its hymns and the piety of the assembly. He breaks out in a rare smile. Tears stream down his cheeks. Recall the sudden and short-lived passion of Andreas on noting the uncanniness of the sun while he does repairs on his roof. Consider the difference. Notice the maudlin state of our protagonist here. Also notice that, on encountering the suicide, Abel rushes back and forth in his lostness, the same Samuel Beckett-rattled back and forth at the end of The Passion of Anna, where the killer drives away and the not tough-enough artist resorts to signs of absurdity.

On following Manuela’s exit from the stage that first night, we become even more vividly aware of her (perhaps fleeting) sensuous priorities. Her departure is given super-closeup, in such a way that areas of her body and her costume define her by region rather than individual. So sanguine is she with her innovation, she seems incapable of fathoming the uniqueness of the register, the pitch of intensity and rigors which could very well spell a tiny range of interaction. A person like Abel, now reduced to parasitical opportunism, would very clearly regard her as a precious dreamer—a precious dreamer with a cash-flow. A person like Manuela, who was fortunate in being in high favor by her landlady/ oracle (who was also an aficionado of radical design [Jugendstil, “Youth-Style”]), might have been shown invaluable wisdom by the friend, were the ancient not fearful of the subject conflict—secretly witnessing Abel’s stealing the other protagonist’s savings and doing nothing about it but telling him, later, “I’m very attached to Manuela. If you forgive me my saying so, I’m as fond of her as if she were my daughter. She’s so kind, naïve [here giving him a hard look]…It’s that there’s all the terrible things going around. I think your sister-in-law is heading for trouble. The thing about Manuela is she doesn’t defend herself. Nothing must happen to her…” Such a gambit being itself a tonal terrain of deadly retreat.

Wearing her woolen cloche on the tram ride home from the night, she finds Abel crumpled up in the doorway to her flat. Holding him up, she unwittingly brings him to the money; but treasures of the specialty of the house emanate along with her own modest effects. Such incisiveness, however, must wait till next morning; and, even then, he starts by blathering away about the family next to them, at Amalfi, where the master of the house, a Supreme Court Justice, would cut open a farm animal to see the heart still beating. As Manuela puts together a breakfast, we notice on the austere but carefully incisive wallpaper, two lithographic circus posters—one, depicting a man and a woman, upside-down, clinging by their feet to a trapeze; and the other showing a woman bare-back rider. No one refers to them for a moment; but you know she would have had long, penetrating times in their presence—not only about the vignettes but the uptakes of the wider tones. Even though he forces upon her a wad of low-value currency, explaining, “You should take the money before I spend it on booze,” she imagines that they could dazzle once again as a high-precision circus act. Perhaps she banks upon her charisma to overcome any obstacle. And, therein, a mood of tailspin burns brightly. The shrunken heart, responds with, “I don’t know. What good is it without Max?.. It’s a nightmare…” She embraces him, in a bid to lift his spirits. “We’re going to do it,” she enthuses. “You think too much… We can do a new number, just you and me. We could make magic. I know a wonderful magician. We could take over his show!” (The initiatives being far from coherent. But here we occupy a play of mood, which impacts in its own ways.) In reply, there’s the one-note, “I don’t know. Since this business with Max…” (And he cries.) Despite the discouragement coming her way, she tries the coquetry, “You’ll be my big brother. We’re going to stick together now…” That his repetitive dirge—“I wake up from a nightmare…”—becomes ludicrous, only confirms that a whole other world buoys her. As she iterates, “Everything is alright! We have everything we need,” it is that “which we need” which possibly turns things thing around for her, leaving the pessimist far behind. Can her upbeat heart hang on? He tells for her his seeing Nazi goons getting away with murder the night before. And she tiptoes around her second job as a hooker for the wealthy. She moves along with, “You’ve been thinking much too much, lately…You’re awfully tired…” (Unspoken and probably confusedly, would be, “You’ve been thinking like and old man!”) “I’m going to look after you, you know… And in a few days everything will be much better. You’ll see…” As she goes to her bemusing job (which he tries to treat as the end of the world), she’s in furs.

The smashing of Manuela’s inadequate roots is both dismaying and uplifting. Abel is obliged to return to the police station to settle details; and thereby the money he has just stolen is confiscated by a matter of routine. At the tail end of his bizarre and revealing brush with justice, Manuela appears there (as hopefully finding a pedestrian clue to what was in fact a fear of life itself, but in hopes that Abel might know what happened to her money). She’s seated at a table, and the brother-in-law walks past her without looking her way. This, by way of a visit to Abel being held for information about Max and a slew of other corpses. He silently brazens his involvement, and adds, “Luckily, I’m in charge of Max’s money…” As the interview proceeds, she loses her concentration, and Abel faults her for lagging. She asks, “Please be nice to me…”

On the day the landlady demands the rat out, leading to Manuela’s angry rupture of a wise friend, our protagonist rallies a bit in visiting a church. But we are now approaching such a meltdown of cogent vision and tone—acceptance of Abel a form of insanity—that the narrative commences to sport auras of (largely, American film) clichés—becoming, in themselves, not only a warning but a fissure leading to depths. (Bergman seizing the singularity for all its worth.) Although he easily stalks her to the site, he totally misses the action. First a flock of candles, with Abel back in the gloom. Overkill, where three would do the trick. She addresses the eccentric American priest; but he’s, at this point, distracted. Bing Crosby would never have slipped that way. She soldiers on: “My father was a magician. My mother was a circus rider. I’ve been in circuses all my life [unlike the upstarts]… I need to speak to somebody, do you understand?… Oh, this guilt is too much for me! And I feel it’s my fault that Max committed suicide… Now I have to take care of Max’s brother. And it’s even worse! Why he’s just like Max. He never says what he’s thinking. He just charges ahead with his feelings and he looks so frightened. And I tried to tell him that we’ll help each other… That’s only words to him. And everything I say is useless. The only real thing is fear! And I’m sick. I don’t know what’s wrong…” The priest asks, “Would you like me to pray for you?”/ “Think that will help?” she asks. “I don’t know,” the expert admits. They kneel together and soon she wonders, “Is it a special prayer?”/ “Yes,” he finds the cogency to declare. (A vehicle, that is, which she’s been delighted by many times in the past; only to let it slip away.) He adds, “We live so far away from God. So far away that God doesn’t hear us when we call out… So we must help each other give each other the forgiveness a remote God denies it. I tell you, you are forgiven for your husband’s death. You’re no longer to blame. [The priest having read between the lines.] I beg your forgiveness for my apathy and my indifference. Do you forgive me?”/ “Yes,” she rather confusedly replies. “I forgive you.” This elicits the clang sound repeatedly sounding at the beginning of the film, sounding to the roots. “That’s all we can do,” he closes. (Leaving the question, “Is that really all we can do?” Could it be that the powers-that-be require our dance/ acrobatic initiative to really rock? Could it be that asking is the wrong gambit. Active partnering would entail graces enough.)

Manuela’s pristine partnering becoming rapidly collapsing, she finds a workhouse connected with Saint Anna’s Clinic (“Please say it’s nice…”), and Abel let’s her know it’s beneath his dignity. On to the cabaret which, that night, is visited by a Nazi unit (one of the highlights being the owner’s beaten to a pulp, somewhat like, much later, the beating from Cliff to an enemy, in Tarantino’s Once upon a Time in Hollywood. Intense action often drawing upon a volume of sensibility missing the mark.) But the most telling moment, from our perspective, is the spectacle (seen from a bird’s eye view) of our protagonist in her avant-garde costume consumed by a terrified throng. (The collapse of mood being our investigative task.) She goes to work in the clinic’s laundry, and she becomes ill from pneumonia. She tells Abel, now working nearby in a vast archive (apt for someone locked away in the past), “I don’t think I can stand it here.” In an echo of her best self, she smiles and says, “It could have been worse.” That night, he beats her up; and melodramatic complaint takes over. “I just say, if you won’t believe, you can go! I’ve done everything to keep us together. I just can’t go on any more…” She hammers on the table. All the savoir faire having abandoned her. Abel cuts out and walks past a group butchering a horse that was once a going concern. The horse’s beautiful head was seen intact, to bring to bear the powers of a creature the vivacity of which far surpasses domestic exigencies. The one who couldn’t stay returns to Manuela’s corpse. He shakes her brutally, hoping to bring her back to life. He had picked her to the bones. (Those faulting Bergman’s cosmic vehicle in preference to Bob Fosse’s domestic and political musical, namely, Cabaret [1972], have been barking up the wrong tree.)

During his stroll to escape Manuela’s last ditch feeling of affection, he activates a study of the difference between Sportin’ Life and lively sport. After stuffing Marks into a barkeeper’s mouth and going on to smash with his bottle the window of a lovingly maintained woolen’s shop, he uses his plush dancing shoes to hoofer-style disappear to an alleyway replete with a young hooker. Once again, as with the raid, the scene is taken from a considerable distance, and at a rather stagey height. His opening, “Go away,” has about it many Broadway tinctures. (The alley is clearly a sound stage.) “Come with me! It’s warm. You can have it any way you want…” “Go to hell,” he studiously emotes. She chuckles, and her delivery seems from Iowa. “Where do you think you are—at Times Square?” she sweetly fusses. A muted honky-tonk drifts their way; and he goes her way. (The sentimental film, Going my Way (1944), with its unorthodox priest, is all over the vignette of Manuela and the American clergyman. Classics on the move. Distress in the mood. The millions to make this film/ tone poem were not wasted, as ridiculous trolls would have it.)

Disabled Abel and the night worker enter a brothel bristling with poor breeding. The prevailing trick soon reveals itself to be humiliation of a crippled, impotent and noisily opinionated black. Though a show-biz tragedy is ready to make you squirm, those of us, remembering Bergman, recall the film, Sawdust and Tinsel (1953), and its routed ringmaster becoming a figure of public and private defeat. With so much slippage in the air, this episode puts us in need of finding a way that works. Manuela’s mother was a circus rider, perhaps making waves in the midst of that corporate collapse. A lady clown, Alma, dazzled for a few moments much of the army, before subsiding to tending to an old bear, whom the beaten boss shot to death, in a cowardly attempt not to look weak. But with the specifics of the brothel, we enter upon a measure of consistently oblivious frenzy for the sake of the enjoyment of empty advantage. The new friends inhabit the world of George Gershwin’s opera, Porgy and Bess (1935). Cowardly Abel toys (like the opera’s villain, “Crown”) with a crippled and fiercely loquacious, Porgy, who bids, to neither sexual nor social effect, to rescue, Bess. “You’re tryin’ to kill me! You’re tryin’ to fuck me! I can’t fuck! Worst bitch in the whole damn world! She’s got fangs, I saw them!” The object of this fury laughs. “That big mouth bitch! I’m not a queer. That’s a goddamn lie!” (A clown show, drifting over to the beaten ringmaster; and the beaten has-been!) Abel would also double here as cynical, “Sportin’ Life,” always the vicious oracle. Abel bets him to come. More humiliation. More of Saint Anna and her security of delivery.

Our denouement entails further rigidity against the prospects of that cogency we’re tracking becoming widespread. There are two instances of Abel’s being the beneficiary of oldsters’ letting their sunny hopes prevail over what is a rather obvious phenomenon of failure to thrive. He crosses paths with the impresario whom he and Max and Manuela starred for. The elder is supple and intense; Abel might as well be headed for palliative care. He disregards the question, “How are Max and Manuela?” In spite of this, the gambler insists, “The circus needs you!” Invited to lunch at a posh restaurant, Abel consumes much alcohol in slight time. He also, from out of a life-long distemper, plunks his sheep skin hat over the head of a nude sculpture. His host tells him, “Nowadays I can get any dance star I want. They all know I pay in dollars…” Disregarding the rudeness and alcoholism, he switches to the day’s newspaper and regards the actions there as more entertainment. He thrills to, “… the massacre of Christians by the Jews… the Bolsheviks coming to Germany and stumbling over the bodies of your women and children…” The showman asks, “Why don’t you say something?” In reply he produces a pedantic doctrine which Anna, the security maven, could have written. “I don’t care about political crap. The Jews are as stupid as everybody. If a Jew gets into trouble it’s his own fault. He gets into trouble because he acts stupid. I’m not gonna get stupid, so I’m not gonna get into trouble.” Tone deaf through the whole exercise.

The second senior, who could have anticipated aberrant performance in Abel, is the Chief of Police, who misreads peevishness for commitment. The Chief has an idea that Max was only one of a large number of victims to a mass assailant, not quite as slick as Anna. The investigation, involving the sibling, begins where Max maxed-out and a hurdy-gurdy man with a little monkey gives the street some shine. On to the morgue, where the person of interest touches upon more than a limited errancy. A series of blood-spattered shrouds confront them; and each station has a link to Anna. Max’s suicide may be light years away from Johan’s, but comparisons can divulge important truths. Abel recognizes the first woman to be shown as having been engaged to his brother. At another perspective, there was Anna forcibly tearing her (understandably fed-up) husband away from a woman he preferred to her. (Cause of death, drowning.) Another incident gives Abel the sense of recalling his father. Repeating the outrage of Anna’s leaving Johan (a father-figure to Andreas) to seem to the world to have butchered a flock of sheep, which brought upon the innocent man such cruelty that he committed suicide, the other father would be another kill of hers. The Chief adds, “Someone stuck a hypodermic needle into this man’s heart. It probably took several hours…” Then there is an aged woman whom Abel has seen but can’t fully detail. “I think she delivered papers. I used to meet her at Frau Lanci’s boarding house. Once she helped me up the stairs when I was drunk, too drunk to make it on my own. Her name is Maria Stahn. She left a very strange letter. ‘The husband was half out of the windshield.’ He worked at the cabaret, in the entrance.” The fallible investigator adds, “We are not certain how he was killed. He seems to have been run over by a truck, but something tells us he’d been assaulted or tortured.” In the land of the prototype of mad safety, there was the treachery of Hour of the Wolf (1968), pertaining to the strange, warning letter; and, then also, Anna, and her note (written by the husband) to Andreas; and a husband killed by her sneakingly catapulting him through their car windshield.

Suckered by the non-acrobat’s bathos, the old cop opens up with, “All over Germany, millions are terrified… but I’d be delighted to see you swing on your trapeze with your peers. That way you fight your fear.” He provides a police escort to a train to Basel, where the circus works at being fearless. But he slips away from the goodwill and disappears forever.

Before he’s mercifully gone, he visits, by way of his archival links, the brain-trust behind that recent plague of violent deaths. There he can measure his own puny pedantry against a far more virulent rationality (another Anna). What could be more appropriate than an Alfred Hitchcock “exciting twist” to send the patrons home feeling that rational goodwill must always prevail. The carriage-trade chum from Amalfi pops up in a lab coat, and delivers a rationale for studies in human endurance (along the way, giving scope for a family trait of sadism). (Abel spends most of the experience covering his eyes with his hands.) With the Chief on his tail, the so-called “heavy” bites his cyanide capsule, while the law shoots away the door. “We are ahead of our time,” the researcher/ melodramatic oracle had assured Abel. “In a few years, science will ask for my documents, to continue our experiment on a gigantic scale. What you have seen are the first steps of a necessary and logical development… The old society, based on extremely romantic ideas of man’s goodness, was all very complicated… The new society will be based on man’s potential and limitations. We exterminate what’s inferior.” (Mood becoming bilious. Melodrama becoming empty.)

Hitch, always leaving the customers with a witticism, has the Chief—that genius of human nature—brag, as to a recent abortive putsch by Hitler, “He underestimated the strength of the German democracy.”

Hovering over the mad professor is his surname, “Vergerus”—the surname of Anna and the surname of a proto-fascist doctor, in the Bergman film, The Magician (1958). They’ll never go away, because cowardice will never go away. Our film today anticipates slight but meaningful progress.

0 notes