#and horns and hair (and also fingernails and the outer layer of hooves) are all made of keratin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I really love this art, and a couple weeks ago I made a new d&d character who's a tiefling bard (their name is Moxy based on the band Moxy Früvous and also the helluva boss character Moxxie), and I wanted to draw art of them in a similar style, even though I have almost no digital art experience lol

I can't draw hands, but I used the two pictures of just Charlie (Faun's Song and Nature Goddess) for reference images and did the best I could :D

Fairytale au

I present you my fairytale charlastor au with Wendigo Alastor and Faun Charlie! I’ve started a comic about how Alastor became Wendigo and I’m also planning to tell a story about how these two met and how different they are as goddess and former human!

Red Moon

Transformation

Wendigo

Faun’s song

Nature Goddess

And references! No, I’m not gonna change family’s last name, I feel like Magne is more suitable for this au. But I feel like redesigning Lilith tho

I will ban everyone who’s gonna be hateful about ship, idea or anything else. I don’t care, I don’t want people who are ready to hurt real people over fiction.

I just want to have fun and chill, okay?

#digital art#dnd oc#how do I draw hands???#thank you op :)#you should check out the rest of their stuff too#NEW EDIT FROM THE FUTURE- HI- I (tried to) GIVE THEM normal tiefling horns after all (2nd image) and also a purple undershirt cuz why not#[THIS IS BACK TO TAGS FROM THE PAST NOW] also Moxy's horns are blue because their hair is dark blue#and horns and hair (and also fingernails and the outer layer of hooves) are all made of keratin#so I figured it would make sense for the horns and hair to be similar colors even though tiefling horns are normally skin color#also because I originally had the horns be skin colored and I felt like that looked ...wrong#I don't really like the bright blue that much either though#also the horns look like they're going off to the side instead of back like I intended#sorry the tags are so long go check out xitsenhella's other stuff thank you bye

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meta Post: Elf Horns

This post is about the speculative biology of the horns of elves in The Dragon Prince. It contains 7 diagrams.

It will cover the possible internal anatomy of the horns, their sensitivity to various stimuli, and several possible functions of the horns. As this is mainly directed at fellow content creators, this could be useful for fanfiction authors, or people designing OCs.

You do not need to have seen TDP to read and understand this post. Information in this post could apply to horned humanoids in other canons as well.

Section 3 details ways an elf infant’s horns might develop, and would be useful for writers of kidfic, or people designing child elf OCs. Section 5 includes some horn-related scenarios that may interest writers, such as what might happen when horns break, if horns are removed in infancy, details for sickfic authors, and what might happen if a Startouch elf sheds their keratin.

My sources will be found in my reblog. There will be easy-to-understand summaries at the end of every section.

Content warnings: This post contains multiple diagrams detailing the possible internal anatomy of horns. The diagrams are clinical and do not contain gore, but I do mention blood, sinuses, mucous membranes, and other such things in text. In the fiction application section, I also mention scenarios that involve harm to children via damage to their horns. If you are concerned that any of this may be a problem for you, please feel free to contact me to ask for details.

Contents:

1. Introduction

2. a) Anatomy of horns

b) Elves with branched horns

c) Sensitivity of horns

3. Horn development

4. Possible functions of elf horns

5. Scenarios for content creators

1. Introduction

Horns are protrusions from the skull of an animal with a core of live bone and an outer sheath of keratin. Keratin is ‘dead’ material, and can also be found in fingernails, hair, and the hooves of some animals. Horns are very distinct from antlers. Horns almost never have branches, for example. Until elves appear whose horns seem distinctly antler-like, I will not be making a detailed analysis of antlers here. Startouch elves probably have horns, not antlers, and will be covered in this post.

n.b. The more technical information about the internal anatomy of horns is almost entirely derived from information on cattle, as due to the fact that we keep them as livestock, there is much more information available about their horns than those of other horned animals. I do, however, offer alternative options for internal horn anatomy of elves.

Summary: Real-world horns are made out of bone covered in keratin. I am assuming that elf horns work the same way. Horns almost never have branches like antlers do, but they do sometimes, and I’ve got a specific section for explaining how that would work for elves with branching horns. I used a lot of information about cow horns to make this post, because there’s a lot of information available on cows and not so much on antelope or gazelles or such.

2. a) The anatomy of horns

I consider two main possibilities for the internal anatomy of elf horns:

Option 1: Elves have a sinus cavity inside their horns.

Option 2: Elves don’t have a sinus cavity inside their horns.

Option 1 is considerably more complex (and interesting for me as an author) so I’ll be spending more time on it.

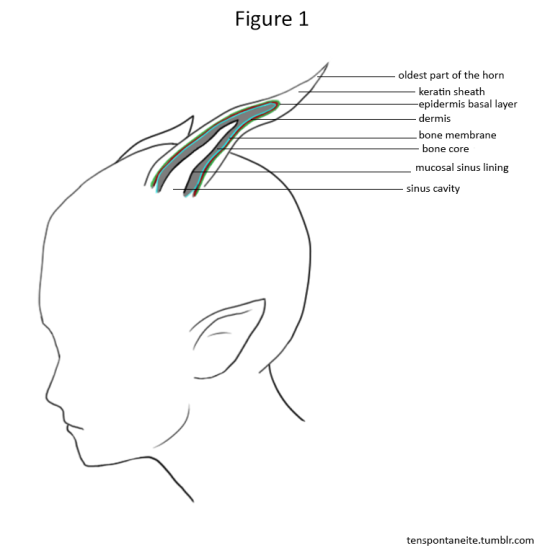

Please see figure 1. This contains a diagram of an elf who does have sinus cavities in their horns. This skull silhouette was traced from a screenshot of Rayla, so her horns will be our main model today.

I’ll be running through the different parts of the horn labelled here, going from bottom to top.

Sinus cavity: This is where the sinus would extend into the centre of the horn bone. If you were to cut open an elf horn, this part would appear a pale pink colour, and would be full of weirdly shaped hollow spaces with kind of mucous membranes. The sinus cavity develops as the elf ages, and older elves will have hollow spaces extending further along their horns than younger elves. This will be mentioned in more detail in the developmental section.

Mucosal sinus lining: What it says on the tin – this is the mucous lining at the edge of the sinus cavity.

Bone core: This is the section of the horn that is live bone. It is vascularised, meaning it has blood running through it. If the horn breaks, it will bleed. The bone core of the horn is slightly narrower at the base of the horn to allow space for blood vessels to enter it from the head. To my knowledge, this is also where the nerves enter the horn.

Bone membrane: Also what it says on the tin – this is the membrane over the bone core of the horn, separating it from dermis and hypodermis.

N.b. Not labelled here: Hypodermis. This would be the skin layer underneath the dermis, the ‘main’ skin layer, but my main source stated that it is not distinct in horns, tending to ‘be one’ with the bone membrane.

Dermis: The ‘skin’ inside the horn. The dermis in horns nourishes the epidermis, and as such can be expected to contain blood, lymphatic cells, and likely nerves as well. The dermis in horns tends to have a very specialised structure compared to dermis elsewhere in the body, having some really weird villi. Now, I’m not completely sanguine on what exactly villi do in other types of skin, but I understand that in horns, their weird structure forms the basis for the structure of the keratin made by the next skin layer.

Epidermis basal layer: This is the layer of skin over the dermis. It produces the keratin that forms the hard outer sheath of the horn, pushing it upwards and outwards throughout production.

Keratin sheath: The hard outer portion of the horn, and what will be visible to outside observers. This can be formed in variable patterns and structures depending on the individual and species – for instance, Moonshadow elves seem to have a loosely curved/spiralling texture on their keratin sheaths. Other elves’ horns may be entirely smooth, furrowed, ridged, or even pronged (as in Startouch elves).

Oldest part of the horn: the tip of the horn is the oldest and densest part, and is the first part that grows in a young elf.

All that described, let’s talk about sinuses.

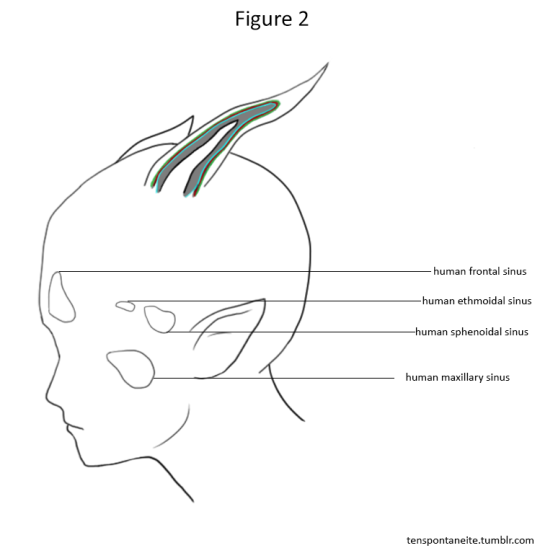

Sinuses are a connected system of hollow cavities in our skulls, lined with mucous layers. They’re connected to our respiratory system, and fill with air when we breathe. Most sinuses drain into the nose through small channels. Humans have several sinuses: the frontal, maxillary, sphenoid, and ethmoid. See figure 2 for rough representation of where these sinuses are located in humans.

I should note that, despite being located at various depths in the skull, all of our sinuses are approximately towards the middle of the skull – in other words, along the same sort of mid-line as the nasal cavity. They’re not exactly in the middle, but they’re closer to it than not.

Now, looking at figure 2, you might notice that those sinuses are all kind of a long way away from the horns, and their hypothetical sinus cavities. Elf horns do seem to be located quite far back on the skull. As such, if they do have sinuses in them, elves almost certainly have additional sinuses to humans, and quite possibly any sinuses they do share with us will differ in structure.

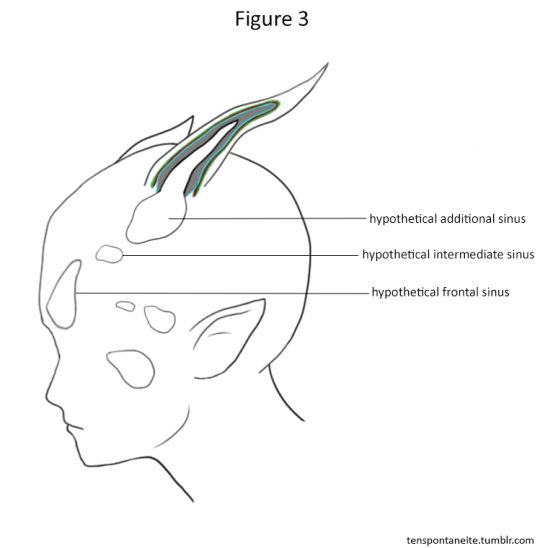

These additional/differing sinuses could go pretty much any way, but I’ll present one possibility in figure 3.

Here, I present an elf with an enlarged and differently-positioned frontal sinus, an intermediate sinus located between the frontal sinus and the horn, and the sinus that extends into the horn cavity. In this case, you might expect the internal skull structure of elves to be slightly different, in order to make room for the extra sinus cavities.

Possible names for the additional horn sinus: parietal sinus, para-frontal sinus.

Possible names for the additional intermediate sinus: prefrontal sinus, para-frontal sinus.

I will be calling the horn-connected sinus the parietal sinus, and the intermediate sinus the prefrontal sinus, as these are probably the most accurate and appropriate names.

All this considered, what are sinuses actually for?

We’re not completely sure.

Sinuses are strange, strange things. One theory is that they’re there to moisten our air, increasing the humidity of air inhaled through the nose. They could hypothetically filter unwanted particles from the air too, or at least some of them. They could, in theory, also help to increase the resonance of our voices.

And, last but not least, having hollow spaces in the skull makes it a bit lighter, which is probably especially helpful for elves with large horns who don’t like neck pain. This would probably be my main argument for why I think elves would have horn sinuses, actually. Heads are heavy, and even without horns to make them heavier, our necks can be pretty rubbish at supporting them. Sinuses would, quite literally, lighten the load.

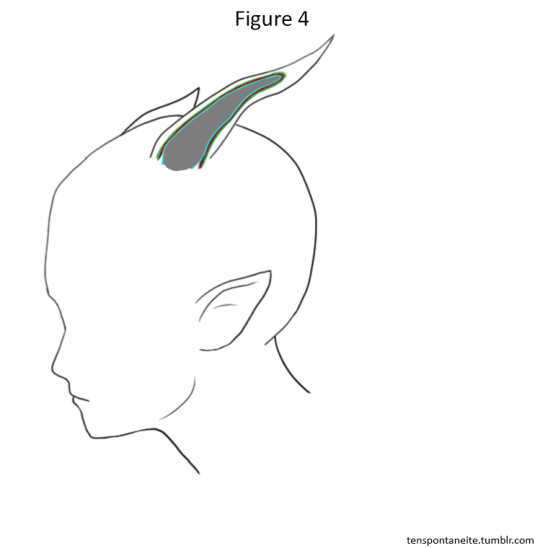

Of course, it’s possible that elves could lack sinus cavities in their horns, per figure 4.

In this case, you’d still expect the horn to have a lot of the anatomical traits we discussed before, like the bone, the bone membrane, the dermis, the epidermis, and of course the keratin sheath. The only difference would be the lack of sinus cavities. I suppose it’s possible the bone could contain hollow spaces inside it to make itself lighter, such as in many bird bones.

Summary of Section 2.a)

Some horned animals have sinuses in their horns. Some horned animals don’t. I explained, using diagrams, how the inside of a horn would work for an elf in both cases – sinus and no sinus. Basically, inside the bone of horns, you either have a hollow space for sinuses, or you don’t. Over the bone you have special skin that makes keratin, and over that you have the keratin part of the horn that everyone sees.

Sinuses are hollow spaces in our skulls connected to our breathing system. If elves have sinuses in their horns, they probably have more sinuses than humans, and in different places. This means the insides of their skulls would be slightly differently arranged. I gave an example of a couple additional sinuses elves could have – the parietal sinus, connected to the horns, and the prefrontal sinus, to connect it to the rest of the sinus ‘system’.

I think it would make sense for elves to have sinuses in their horns, since it would help make their horns lighter, which would make elves with large horns less likely to get horrible neck pain.

2.b) Elves with branched horns

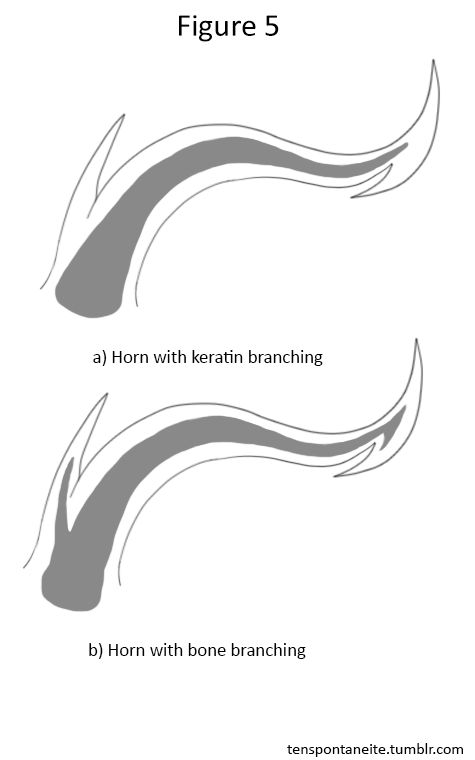

We have observed that at least one elf has horns that appear to branch. In our own animal kingdom, there is no animal whose horns contain branched bone. However, there is an animal whose horns have branching keratin: the pronghorn. In The Dragon Prince, we therefore have three basic options for branching elf horn structure. See figure 5.

a) The horn has a bone core that does not branch, but a keratin sheath that does branch. This is similar to the function of the pronghorn’s horn in nature, and is what I’d probably go with personally. This also affords an interesting possibility for elves with branching horns: the pronghorn sheds its keratin sheaths yearly and regrows them.

If elves shed their keratin in this fashion, it might happen yearly, or far more rarely. It would probably represent a time of increased energy needs for the elf – they would likely require more food to supply the regrowth. It’s also possible that if the keratin sheds down to the epidermis, the horn core may be sensitive to the touch until the keratin regrows.

b) The horn bones function differently to known examples in the Earth animal kingdom, and do branch. This would mean the bone core extends at least vaguely into every branch of the horn, and has its own dermis and epidermis to grow keratin.

c) (Not pictured) These elves don’t have horns, they have antlers. I’ll not go into this in depth, but if these elves have antlers, you can expect them to shed and regrow on a regular cycle. During growth they will be covered in a velvety coating that is somewhat sensitive, and the antler will be full of blood. If cut they will bleed very profusely. When the antler is fully grown, the velvet coat is scratched off, and the antler is hard, smooth, and generally pale to darker brown in colour. It is no longer sensitive, less vascularised, and can be considered ‘dead’. Eventually it will fall off and the cycle will begin again.

Summary of section 2.b)

Elves whose horns branch could work in a few different ways. Either 1, they’re not actually horns at all, but antlers. 2, the bone of their horns doesn’t branch, but the keratin does, and they might even go through a shedding cycle. Or 3, the bone in their horns branches, unlike any animal on Earth.

2.c) Sensitivity of horns

Light touch: The horns are supplied by nerves. However, they’re also covered in ‘dead’, insensitive keratin, so you can pretty much guarantee they will not be sensitive to fine touch. Light touches, gentle breezes, even stronger breezes – they almost certainly won’t be sensitive to any of that. If a leaf or feather brushes their horn, they aren’t going to feel it.

Pressure: We can expect elves to be aware of pressure or weight on their horns, if only because this will exert pressure and weight on the skull by extension, or change the weight of the horns in a way perceptible to the elf. An elf would notice if you grabbed their horn unless you did it very, very lightly. You could probably get away with a light poke without them noticing. As stated before, they will not be sensitive to fine touches. If the dermis or epidermis under the keratin is sensitive to touch, then a sufficiently tight grab on a horn could maybe be felt through the keratin, but it would need to be a really emphatic grab, and even then I’m not sure it’s likely.

Pain: We can be certain that, if a horn is broken, it will really hurt. It’s possible then that a sufficiently hard impact – hitting one’s horn extremely hard on the ceiling, for instance – could cause pain to the inner part of the horn. It would also probably cause pain to the hornbed, the skin around the base of the horn, and possibly the skull. If we assume horn sinuses, it’s also very likely that severe colds or sinus infections could cause ‘horn-ache’.

Temperature: This one is difficult to gauge. Animals with horns are quite difficult to interview about the finer details of what they are sensitive to. What we do know: many horned animals use their horns to play a role in regulating their body temperature. Animals adapted to hot climates can even experience frostbite in the ends of their horns if they’re somewhere very cold. I think it’s possible that extreme cold could cause a sort of ache in the horn. I feel that sensitivity to temperature would only happen if the ambient hot or cold were strong enough to warm/cool the keratin layer and trigger hypothetical receptors on the dermis. This could really go either way.

Visceral awareness: It is very likely that elves would be very aware of the position and size of their horns. This would be due to a combination of the weight of the horns on their head, learned responses, and possibly a vague visceral sensitivity to the nerve-supplied inner horns that allows the elf to feel them there, as with any body part.

We can be sure that elves will have a well-developed awareness of how tall their horns make them, and how much they have to duck to get themselves and their horns beneath obstacles. Elves who get their horns stuck on things a lot are either very scatterbrained and/or clumsy people, have done a lot of growing recently, or any combination thereof.

Possible exceptions: If Startouch elves shed their keratin, then it is possible the layer of keratin-producing epidermis would be sensitive to light touch and temperature until the keratin grows back in. Possible, but not certain.

Summary of section 2.c)

Horns wouldn’t be sensitive to light touches, but they do have nerves running through the bone and skin inside them. If they’re broken, it will be very painful, and will bleed. If an elf hits a horn very hard on something, it could make the inside of the horn hurt. Elves will be aware of pressure or weight on their horns, like if their horns are caught on something or if someone is resting a hand on one. They’ll probably have a strong awareness of how tall their horns make them and where their horns are positioned when they move around. There’s a chance the inside portions of horns could be able to feel the difference between hot and cold.

3 Horn Development

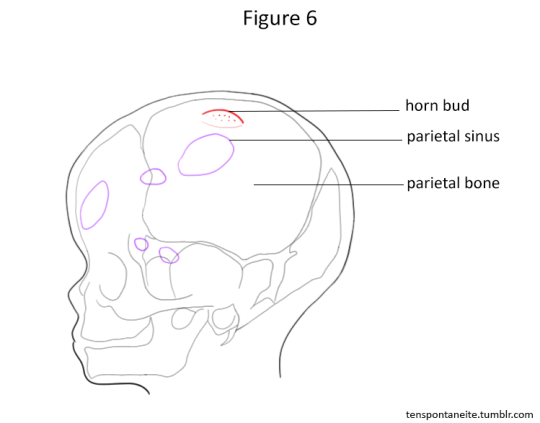

Baby elves, probably to the relief of their mothers, may not be born with horns. The newborn elf might instead have two darker-coloured patches of hairless skin on their skull, where the horns will grow from. Under the skin, the ‘horn bud’ will already be present, and will have been since probably around half way through gestation. It will likely be able to be felt through the skin. Please see figure 6.

This figure labels the horn bud, the speculative parietal sinus, and the parietal bone the sinus is named for. Not labelled are the speculative prefrontal sinus, the frontal sinus, the ethmoidal sinus, the spheroidal sinus, or the remaining skull bones. This figure is derived from a diagram linked in the sources.

The horn bud is likely to have unusually pronounced nerve growth around it, both prenatally and in infancy, meaning it will be an especially sensitive area on the infant. It’s hard to say what form of sensitivity this would take – could be ticklish, could be soothing. Consider a concept: elf parents stroking their newborn babies’ hornbeds as a common form of affection. Some of this sensitivity around the base of the horn could well remain later into the elf’s life – while it wouldn’t be as sensitive as in an infant, it’s possible that the skin around the bases of elves’ horns could be noticeably more sensitive than the rest of the scalp.

The newborn’s horn buds are essentially tiny, well, buds. Buds of cartilage, bone-producing cells, and keratin-producing cells. They are separate from the skull and not connected to it – yet. The horn will begin growing from birth, and depending on elf newborn growth rate, it may take anywhere from three weeks to several months to protrude a centimetre from the skull. At this stage, it is connected to skin rather than bone on the skull, and is mostly cartilaginous rather than bony. You would be able to poke the horn nub and shift it back and forth a little.

In time, the developing horn produces bone and keratin and fuses to the bone of the skull, and can no longer be wobbled around. We can only guess when this would happen in elf infants. I would estimate somewhere from three to six months, but that’s a very rough guess.

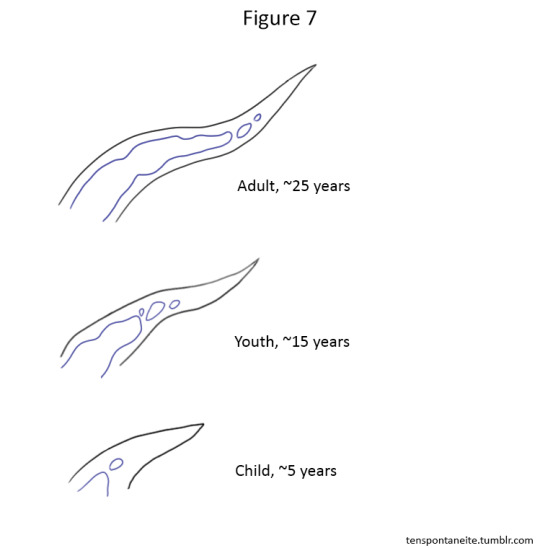

In cattle, the sinus cavities begin developing into the horns at around 12 months of age. This would likely occur much, much later in elves. I would think these sinuses might not start fully extending into the elf’s horns until they were at least five years old, possibly even later. The sinus cavities continue to grow in the horns as the elf grows older; an elf fifty years old would likely have a hollow interior almost all the way along their horns. See figure 7 for a possible progression of the development of the sinus cavities in elf horns.

Alternatives: Some horn-bearing animals are born with horns already present. Elves could be similar, and emerge from the womb with small horns already on their little skulls. These would likely not be any longer than a few centimetres. They may or may not be fused with the skull, but would not have any sinus cavities yet.

Summary of section 3)

I think it’s likely that baby elves are born with the tiniest, tiniest bumps of developing horns under the skin on their skull. If they’re born with any visible horn at all, it won’t be any longer than a couple of centimetres. When elves are born, their horns probably aren’t connected to their skull yet – the horn might fuse to the skull at around 3 months of age. The places where baby elves’ horns grow in are probably very sensitive. Maybe elf parents tend to stroke them. Some of this sensitivity could remain later in life - hypothetically, the skin around the base of the horn could be more sensitive than the rest of the scalp.

If elves have sinuses in their horns, these take a long time to start growing in. The parietal sinus will start growing into the horn maybe at around five years of age. An older adult elf will have far more hollow sinus space in their horns than a younger adult or a child. This means older elves will have more hollow horns.

4 Potential functions of elf horns

This section will propose and evaluate potential purposes for elves’ horns.

Please note: this section heavily assumes that elves have some sort of evolutionary history, and that they did not spring fully-formed from their primal sources however many thousands of years ago. Each subsection will contain references first to ‘early’ elves, who would be the primitive ancestors of elves, and then to modern elves.

a) Fighting, rivalry, and inter-elf disputes

This is the least likely of all options. While many horned animals use their horns to fight each other for territory, mates, or just because they took a disliking to each other, this would not be feasible for elves.

All horned animals on Earth are quadrupeds, which already puts them in a more viable position to use their horns as weapons, as they don’t need to bend forwards as far to headbutt something with their horns, or lock horns with each other. An elf, comparatively, would need to bend over into a downright silly position to get their horns to bear on an opponent. This would be easier for hypothetical elves with forwards-pointed or curved horns, but they would still encounter other issues.

Horned animals tend to have more powerfully built and supported necks than elves. Elves seem to have similar neck arrangement to humans, and as such we can assume they’re not made to withstand significant force applied to the head any more than we are. Even if an elf tried to use their horns to whack someone else, the combination of the position they would need to be in, and the force of impact, would probably cause very serious damage to their necks over time.

It is technically possible that very, very early ancestors of elves were quadrupedal, and had better structural arrangement for using horns as weapons. The process of evolution from a quadruped to an elf would be long enough though that the horns probably (probably, not certainly) would have been selected out of the genepool once they stopped being useful for fighting, unless they had some other useful purpose. Like one of the others yet to be mentioned in this section.

Implications for modern elves: Whether or not horns evolved as weapons, if horns are viewed as weapons, a posture with the head bending forwards towards someone could be seen as aggressive or confrontational. Lowered or brandished horns could be elf-specific body language cues.

b) Self-defence against predators

This is still fairly unlikely, but not as much so as a). Elf horns, especially backwards-pointing ones, could hypothetically be a deterrent against predators with a tendency to ambush or attack from behind. It would make the back of the neck a less tempting target, as there would be pointy things near there that could poke your eyes out if you tried to go for it.

If elf horns do serve a defensive purpose, it would probably be more as a passive deterrent against neck attacks than as weapons the elf could use. If, for instance, an elf were attacked from behind, they probably could jerk their heads backward to gore the attacker, but they likely wouldn’t be able to do it with much force due to limited neck strength, so the defensive damage they could cause would probably be quite superficial. They might also damage their own necks in the process.

Implications for modern elves: If horns do serve a defensive purpose, an elf might have a reflex when being attacked/startled from behind to jerk their heads backwards to hit the assailant with their horns.

c) Some sort of magical purpose

There is basically nothing concrete in canon that would indicate this, but nothing that would directly refute it either. Horns could, in theory, somehow facilitate an elf’s connection to their primal, perhaps as a repository of their arcanum. I’m a bit sceptical of this possibility, but I’m including it just in case.

Implications for modern elves: Elves who break their horns may be unable to cast magic as well or at all, if they were a mage. If horns have a fundamental connection to the arcanum, it’s possible that an elf with broken horns might not be able to access innate abilities, such as a Moonshadow elf’s Moonshadow form. If this is the case, there might well be considerable fear and even stigma surrounding the idea of horn loss.

d) Thermoregulation

This one is fairly likely. As previously mentioned, many horned animals on Earth use their horns as one way to help them control their body temperature. Horns contain live bone, which means they contain blood vessels. Assuming these blood vessels are capable of the same things most blood vessels are, this means they can dilate (get wider; vasodilation) or contract (get thinner; vasoconstriction).

These are functions used by the body to control how much heat is lost through the blood. If the blood vessels are dilated, more blood is running through them at once, meaning that there’s more blood at the surface to lose heat from. Vasodilation is used to lose heat when the ambient temperature is too hot. The opposite is done when the ambient temperature is too cold – the blood vessels contract so that they’ll lose less heat from the blood.

This would make horns more useful for heat loss than heat retention, as the presence of horns always provides more surface area to lose heat from than the absence of horns.

The likeliness of this depends heavily on where elves originate from. It is entirely likely that different kinds of elf would differ in the thermoregulatory tendency of their horns. We would see certain physical differences between types of elf if this is the case:

Elves who need to lose heat through their horns would have thinner keratin sheaths on their horns. Elves who need to keep heat as much as possible would have thicker keratin sheaths on their horns.

My personal candidate for ‘most likely to use horns for thermoregulation’ is Sunfire elves. There’s two possibilities for them: that their Sunfire abilities make them need ways to lose heat to stabilise body temperature, or that they’re not in danger from high temperatures and instead are very vulnerable to cold. Technically they could also not suffer from high temperatures and also not be vulnerable to cold, but in the context of thermoregulation, the first two are most important when talking about horns.

Sunfire elves vulnerable to cold would have thick keratin in their horns. Sunfire elves vulnerable to overheating would have thin keratin. I personally think the former is much more likely, because the amount of heat they’re seen channelling is more than could be offset by a pair of heat-sink horns.

Implications for modern elves: Elves adapted to hot regions and to losing heat through their horns would be more vulnerable to cold. Their horns will lose heat for them whether they want it or not. If they end up somewhere cold enough, they can even experience frostbite in their horns. If they end up somewhere really cold, they could also probably experience horn frostbite whether or not they’re hot-climate adapted.

e) Sinuses

If we assume the ‘elves have horn sinuses’ theory, then the extra sinus space afforded by their horns could be very important to their biology. We may not be completely sure what sinuses are actually for, but bodies in general seem pretty adamant that they’re important and need to exist.

If elves have horn sinuses, this means their horns fill with air when they breathe. That’s pretty cool.

Implications for modern elves: Mainly apply if an elf loses a horn or has them removed at a young age, or gets a sinus infection. This will be covered in more detail in section 5) Scenarios for content creators.

f) Mate selection

This is probably the likeliest purpose for elf horns of them all: that their horns developed at least in part as a characteristic that influenced how primitive elves selected their mates. From this perspective, the horns of an elf could be called a secondary sexual characteristic, which means that they would be part of how ancient elves chose mates, but not directly part of elf reproductive function. In elves, horns of a certain size might signal that their bearer is old enough to be searching for a mate. They would also have been an indicator of how fit and healthy the elf had been over their lifetime, as malnutrition during development can affect the shape, size, and texture of horns.

In nature, animals with horns tend to select mates with larger horns. This would partially be because of the defensive capacity of animals with horns, which doesn’t apply as much to elves. However, as larger horns represent a greater energy expenditure to grow and maintain, they indicate that the potential mate may be healthier and stronger than rivals. This would be especially true for any elves who might shed any portion of their horn, such as hypothetical antlered elves, or the hypothetical pronged keratin of Startouch elves.

Being part of mate selection would explain why elves have horns even if they don’t serve any other useful function. For instance, if elf horns are useless for self-defence, don’t have sinuses, don’t thermoregulate, and don’t play a role in magic, there would be no point in having them. Growing horns would be expensive in energy, using up limited biological resources that could be spent growing or maintaining other parts of the body instead. But nature shows us again and again that many animals will grow very energy-expensive body features, such as a peacock his tail, if it might attract a mate.

If there isn’t any other obvious, very useful reason for elves to have horns, the only remaining possibility is that they contributed to mate selection.

Implications for modern elves: We can expect elves to be conscious of the appearance of their horns much as many humans are conscious of the appearance of their hair. We can expect elves to consider certain horn-related characteristics attractive in other elves. They may have preferences for certain horn shapes, as humans may have preferences for certain hair or eye colours.

We can expect elves to visually enhance their horns and make them more noticeable, such as by decorating or ornamenting them – which, I must point out, is indeed what elves seem to do in canon.

Elves may also easily notice things about each others’ horns that indicate poor health, much as we would notice someone looking sick and pale.

Summary of section 4)

Elves probably don’t consider horns to be weapons for fighting or self-defence. If they tried to use them to fight, they would probably damage their necks. It’s still possible that certain ways of holding one’s head and horns could be elf-specific body language, though – like lowered horns meaning anger or aggression. It’s possible that elf horns might be involved in their magic, but we’ve seen no sign of it in canon yet.

Elf horns could be used to help regulate body temperature – if this is true, some elves will be more sensitive to cold, because their horns are designed to lose body heat. They might even get frostbite in the ends of their horns. If elves have sinuses in their horns, their horns would play a role in maintaining their breathing system, and would be lighter than you’d expect big head-mounted horns to be.

If elf horns aren’t useful for any of these things, or even if they are, the most likely possibility for why elves have horns: early elves selected mates based on what their horns looked like. This would mean that modern elves probably consider horns something they can be attracted to in other elves, like nice hair or hands or eye colour. Elves will probably want to make sure their horns look nice and are presentable. This seems very likely, since canonically, elves do decorate their horns, drawing attention to them and making them look more interesting.

5 Scenarios for content creators

This section is directed at people who produce content involving elves, or horned half-elves. This could be writing, producing OCs, or anything of the sort. This section will involve a fair bit of discussion of horn breakage, as well as intentional horn removal in adults and children.

Horn breaking

If the very tip of a horn is broken off, it may not bleed. It will probably not grow back.

If a horn is broken further down the horn, it will be very painful, and will definitely bleed. There is a chance that it may grow back. Someone who has recently suffered a broken horn will probably want to stop it from bleeding, try to prevent infection, and use some variety of painkiller.

If your elves have horn sinuses, infection may be likelier when the horn is broken, and could spread to the respiratory system quite easily. It could also interfere with the natural function of the sinuses.

Side note on breaking sinus-bearing horns: since the air the elf breathes will flow in and out of their sinuses, if your elf has really bad breath and breaks a horn, you’ll be able to smell it in the horn.

Horn removal

Removing an adult elf’s horns, or the horns of a child, would be an incredibly painful and traumatic procedure. It could take them a long time to recover, and they could have difficulty adapting afterwards, possibly having issues with getting used to the lack of weight on their heads. To remove established horns, you would need to break or saw them off, which would cause significant pain and bleeding.

Removing the horns of a baby is still painful, but easier. If you have a child young enough that their horn buds haven’t fused to their skull yet, the procedure is known as ‘disbudding’, and the horn bud can be removed to stop the horns from growing at all. As the hornbeds of infants are very sensitive, this will cause them pain for days if they aren’t provided with medication, though the wound itself will heal quite quickly. There are several methods for disbudding, used on cattle, that can be researched by any content creators who care to. If you’re writing about a baby half-elf whose parent wants to hide their elven heritage, you might choose to have them disbudded. Removing the skin at the top of the horn bud can also prevent horns from growing.

Important note: if your elves have horn sinuses, removing the horns of a young child will cause developmental issues. If those sinuses would naturally grow into the horns, that means they need to be there. In the absence of horns to grow the sinus cavity into, the parietal sinus will make room in the skull itself, leading to a bulging cranium. An elf child who grows up without horns will have a visibly misshapen skull. As this has only been observed in dehorned/disbudded cattle, it’s unknown what effects this could have on the cognition of a sapient being like an elf. It could have a whole host of neurodevelopmental effects.

Sickness

If your elves have horn sinuses, then severe colds, flu, or sinus infections will probably give your elf horn ache. This could be handy for anyone who likes to write sickfics, as it’s a new and exciting way you can cause your characters misery.

Shedding

If your elf has antlers or is a Startouch elf with keratin prongs, they will shed their keratin from time to time. How often this might happen is up to you. In pronghorns it happens yearly, but you could easily synchronise your elf’s shed with some variety of cycle inherent to their primal source, or something else. They will probably be hungry when they are regrowing their keratin. It may or may not itch. While the dermis is exposed, it may or may not be sensitive to light touch.

Malnutrition

An elf who wasn’t eating well or who was sick a lot when their horns were growing might show signs of it on their horns. Inconsistent diet or high energy needs can make energy divert from growing the horn, which can lead to ‘ridges’ in the keratin where it’s thinner or a different texture to usual. If an elf had been sick or starving a lot as a child, another elf would probably be able to tell by looking at the shape or surface of their horns.

Summary for section 5)

Broken horns will hurt and bleed, and might get infected. They may or may not grow back, depending on a lot of circumstances we don’t understand well.

Removing horns of an adult or child would be incredibly traumatic and painful, and would take a while to recover from. Removing the horns of a baby would be painful but less traumatic, as you can remove the ‘buds’ of the horns before they have a chance to connect to the skull and grow. If your elves have horn sinuses, removing the horns of a baby or child will cause their skulls to become visibly swollen and misshapen as they grow.

Elves whose horns branch may or may not shed the hard outer layer on a cycle. If elves have sinuses in their horns, their horns may ache when they’re sick. If an elf had a bad childhood with a lot of sickness and not enough food, it might be visible in the surface texture and shape of their horns.

That’s about it for now.

Final word: I made this for fun, because whenever I start asking questions about worldbuilding details, especially details about speculative biology or metaphysics, I am basically incapable of stopping myself from going on a maniacal research-and-speculation spree. I wrote it up and posted it because this fandom is currently active, and I hope this information might help or inspire fellow content creators. If you use my research at all, or even just found it interesting, please let me know! I’d be delighted to hear about it.

This post presents things I think are possible. They don’t have to be the only way things are. These are just possibilities I came up with while researching a lot, and they are possibilities that I like and will probably use in my own writing. I am not looking to have arguments about this post. Cheers. Please check the reblogs for my sources.

#the dragon prince#tdp#tdp meta#the dragon prince meta#tdp elves#tdp moonshadow elves#tdp startouch elves#tdp sunfire elves#speculative biology#metahuman biology

1K notes

·

View notes