#and calling Central Europe 'the former Russian empire '

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm begging video essayists to read and cite actual history. You would not believe how many I've clicked off of for very basic errors. Not bad interpretations or arguments; just very basic factual errors.

#historian consumes media#i just clicked off of one for the tripple whammy of: calling the Pale of Settlement 'modern day Germany'#showing liberty leading the people for the French revolution#and calling Central Europe 'the former Russian empire '

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

For 700 years, Moscow has expanded through relentless land grabs, growing into the largest country on Earth while subjugating countless nations.

In a recent video address, President Zelenskyy appeared wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the slogan “Make Russia Small Again.” But this isn’t just a catchy phrase—it’s a call for historical justice and a reminder of Russia’s centuries-old imperial ambitions.

The T-shirt displays a map of the Grand Duchy of Moscow as it was in 1462, under the rule of Prince Ivan III, who sought to break free from the Golden Horde’s dominance. This era marked the beginning of Muscovy’s expansionist campaigns, during which it claimed lands beyond its borders. In the following years, neighboring principalities such as Yaroslavl, Tver, Ryazan, and Rostov were conquered—the same region that made headlines in August 2024 when Ukrainian forces advanced into it.

Even back then, Moscow employed methods that would become its standard practice for centuries—deportation. After conquering the Novgorod Republic, Moscow forcibly relocated its population to other regions. This move was designed to crush any resistance, as Novgorod had long been independent and a powerful rival to Moscow. By dismantling its center of influence, Moscow eliminated any hope for independence and silenced the potential for protest.

It was Ivan III who first declared himself “Tsar of All Rus,” even though he had never ruled over the lands of Kyivan Rus and merely aspired to conquer them. Over time, his ambitions extended to the northern territories of modern Ukraine—Siveria and Chernihiv regions.

The territory of Tatarstan, where the BRICS summit took place in Kazan in 2024, was conquered in the mid-16th century. These lands have never historically belonged to Russia.

In the following centuries, Moscow simultaneously pushed in all directions—deep into Siberia, south to the Caucasus, even waging war with modern-day Iran, while also advancing westward. The empire continuously grew, fueled by a desire to extend its global influence. When Peter I proclaimed the Russian Empire in the early 18th century, he claimed to be “reclaiming lands,” but in reality, it was a relentless campaign of conquest. Like every other empire, Russia’s expansion was built on the systematic expansion of its territories and subjugation of the peoples within them.

A particularly revealing example is Alaska. Russia sold the territory because it lacked the resources to maintain control, while the U.S. initially hesitated over whether it was worth purchasing.

Even in the 20th century, after the collapse of the Russian Empire and the rise of the Soviet Union, Russia continued its territorial conquests. In 1939, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—a secret agreement between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union—was signed. This pact divided Poland and carved out spheres of influence in Eastern Europe, effectively igniting the start of World War II.

While global empires were letting go of their colonies and former vassals were gaining independence, the Kremlin remained focused on expanding its influence. Moscow backed the war in Korea, as well as numerous other military conflicts, particularly in Asia. Its socialist-communist reach extended well beyond Asia.

Russia is a vast prison of nations. Over centuries, it has conquered vast territories, and in doing so, has not only seized land but also sought to erase the identities of the peoples it subjugated—just as it did in Novgorod. Native inhabitants were deported and resettled elsewhere. Crimean Tatars were forcibly expelled from Crimea, while people from central Russia were relocated to Ukraine’s Donbas.

The “Make Russia Small Again” T-shirt symbolizes a call for historical justice: Moscow was a principality in 1462. The history of the territories beyond serves as a reminder that Russia’s big size is the result of imperial conquest, with many nations still trapped in a sprawling colony.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Speculation on life in Europe in the hunger games

During the 40s D13 made expeditions to Eurasia, which has a population of 3 million and is ruled from the land once known as Russia. Europe was even harder hit then Panem by the cataclysm. 3 million lived in Eurasia a smaller population then Panem. The largest population concentrations were in Russia, Former Switzerland, and Scandinavia. Just 21,000 lived in Britain, 10,000 in France, 30,000 in Germany. Western Europe constituted the backwater of Eurasia.

The Russian government survived the cataclysm and was able to take advantage of the benefits provided by global warming, western Europe was the hardest hit hy the fall of world trade, the nuclear exchanges and rising sea levels.

Southern Europe was hit both by the expansion of the Mediterranean and the far hotter climate, but avoided the worst of the nuclear exchanges.

Europe held strong agianst Russian invasion but ultimately fell to Russia.

Western European resistance ended when Russia nuked France a small territory with a tiny population with most of western Europe's stockpile. Left defenseless the rest of Europe was forced to surrender. It did so only reluctantly.

Russia is an autocracy claiming to be hyperboria and Eurasia. It culturally assimilated the rest of Europe enforcing a mono culture.

Russia was as hard hit as Panem and as deranged as Panem yet defeated the west led by Switzerland which was a confederation. With centralization, the element of suprise, large Russian forces nuked France and routed the Swiss armies. The empire it founded called itself "Eurasian Hyperborea"

The Eurasian empire brought as much fear to Europe as Genghis Khan once did but despite its best efforts the feared foe crushed them. The confederates did not surrender and fought to the last but the hordes were not stopped. All leaders of the confederation were executed or fell in battle. Europe still didn't give up and it took 60 years for all rebels to be killed. Hyperboria has ruled a pacified Europe for 144 years at the time of the original series. D13 recieved support from cells of European rebels in the first rebellion and was In sporadic contact but European rebels could not provide any aid and were mere insurgent cells by this point.

There is a European outpost in Greenland,Iceland consisting of refugees from Europe almost similar to 13 after the first rebellion but they have made little progress on returning to the mainland.

Eurasian hyperboria does not give a shit about Panem's freedom has pro capitol sympathies. Though they've ruled Europe for 144 years without any rebel interference.

Though their opinion is unknown due to the lack of information.

The capitol of Eurasian Hyperborea is Onega. The ruler is called a "Vozhd"

The current ruler is Volodomir Shoigu"

The tune of the hyperborean anthem is the tune of Putin and Stalin the soviet anthem tune.

#the hunger games#everlark#peeta mellark#katniss and peeta#mockingjay#thg katniss#suzanne collins#katniss everdeen#thg

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

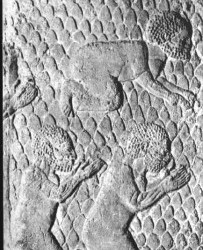

Ancient Hebrews of Lachish

Introduction: According to the standard Jewish Encyclopaedia 96% of all the Jews known to the world today are the descendants of the Khazar tribes of Russia, eastern Europe and western Mongolia; these are the Ashkenazi Jews, the other major sect of the Jews are the Sephardic jews, and they are a bastard people from the mixing of the Canaanites, Hittites, Amorites, Perizzites, Hivites, Jebusites, Girgashites, Kenites, Edomites and some true Israelites. the Jews have never been Isrealites; they are not Israelites now; and they will never be Israelites.

Encyclopedia Americana (1985):

“Ashkenazim, the Ashkenazim are the Jews whose ancestors lived in German lands…it was among Ashkenazi Jews that the idea of political Zionism emerged, leading ultimately to the establishment of the state of Israel…In the late 1960s, Ashkenazi Jews numbered some 11 million, about 84 percent of the world Jewish population.”

The Jewish Encyclopedia:

“Khazars, a non-Semitic, Asiatic, Mongolian tribal nation who emigrated into Eastern Europe about the first century, who were converted as an entire nation to Judaism in the seventh century by the expanding Russian nation which absorbed the entire Khazar population, and who account for the presence in Eastern Europe of the great numbers of Yiddish speaking Jews in Russia, Poland, Lithuania, Galatia, Besserabia and Rumania.”Khazar: Ashkenazi Modern Jew

The Encyclopedia Judaica (1972): The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia:

“Khazars, a national group of general Turkic type, independent and sovereign in Eastern Europe between the seventh and tenth centuries C.E. During part of this time the leading Khazars professed Judaism…In spite of the negligible information of an archaeological nature, the presence of Jewish groups and the impact of Jewish ideas in Eastern Europe are considerable during the Middle Ages. Groups have been mentioned as migrating to Central Europe from the East often have been referred to as Khazars, thus making it impossible to overlook the possibility that they originated from within the former Khazar Empire.”

The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia:

“The primary meaning of Ashkenaz and Ashkenazim in Hebrew is Germany and Germans. This may be due to the fact that the home of the ancient ancestors of the Germans is Media, which is the Biblical Ashkenaz…Krauss is of the opinion that in the early medieval ages the Khazars were sometimes referred to as Ashkenazim…About 92 percent of all Jews or approximately 14,500,000 are Ashkenazim.”

The Bible: Relates that the Khazar (Ashkenaz) Jews were/are the sons of Japheth not Shem:

“Now these are the generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth: and unto them were sons born after the flood. The sons of Japheth;…the sons of Gomer; Ashkenaz…” (Genesis 10:1-3)

New Standard Jewish Encyclopedia, page 179,[GCP pg 68]

“ASHKENAZI, ASHKENAZIM…constituted before 1963 some nine?tenths of the Jewish people (about 15,000,000 out of 16,5000,000)[ As of 1968 it is believed by some Jewish authorities to be closer to 100%]”

The Outline of History: H. G. Wells,

“It is highly probable that the bulk of the Jew’s ancestors ‘never’ lived in Palestine ‘at all,’ which witnesses the power of historical assertion over fact.”Ancient Hebrews

Under the heading of “A brief History of the Terms for Jew” in the 1980 Jewish Almanac is the following: “Strictly speaking it is incorrect to call an Ancient Israelite a ‘Jew’ or to call a contemporary Jew an Israelite or a Hebrew.” (1980 Jewish Almanac, p. 3).

By

The Bishop

Spread the love

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Text

In February 1994, in the grand ballroom of the town hall in Hamburg, Germany, the president of Estonia gave a remarkable speech. Standing before an audience in evening dress, Lennart Meri praised the values of the democratic world that Estonia then aspired to join. “The freedom of every individual, the freedom of the economy and trade, as well as the freedom of the mind, of culture and science, are inseparably interconnected,” he told the burghers of Hamburg. “They form the prerequisite of a viable democracy.” His country, having regained its independence from the Soviet Union three years earlier, believed in these values: “The Estonian people never abandoned their faith in this freedom during the decades of totalitarian oppression.”

But Meri had also come to deliver a warning: Freedom in Estonia, and in Europe, could soon be under threat. Russian President Boris Yeltsin and the circles around him were returning to the language of imperialism, speaking of Russia as primus inter pares—the first among equals—in the former Soviet empire. In 1994, Moscow was already seething with the language of resentment, aggression, and imperial nostalgia; the Russian state was developing an illiberal vision of the world, and even then was preparing to enforce it. Meri called on the democratic world to push back: The West should “make it emphatically clear to the Russian leadership that another imperialist expansion will not stand a chance.”

At that, the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, Vladimir Putin, got up and walked out of the hall.

Meri’s fears were at that time shared in all of the formerly captive nations of Central and Eastern Europe, and they were strong enough to persuade governments in Estonia, Poland, and elsewhere to campaign for admission to NATO. They succeeded because nobody in Washington, London, or Berlin believed that the new members mattered. The Soviet Union was gone, the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg was not an important person, and Estonia would never need to be defended. That was why neither Bill Clinton nor George W. Bush made much attempt to arm or reinforce the new NATO members. Only in 2014 did the Obama administration finally place a small number of American troops in the region, largely in an effort to reassure allies after the first Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Nobody else anywhere in the Western world felt any threat at all. For 30 years, Western oil and gas companies piled into Russia, partnering with Russian oligarchs who had openly stolen the assets they controlled. Western financial institutions did lucrative business in Russia too, setting up systems to allow those same Russian kleptocrats to export their stolen money and keep it parked, anonymously, in Western property and banks. We convinced ourselves that there was no harm in enriching dictators and their cronies. Trade, we imagined, would transform our trading partners. Wealth would bring liberalism. Capitalism would bring democracy—and democracy would bring peace.

After all, it had happened before. Following the cataclysm of 1939–45, Europeans had indeed collectively abandoned wars of imperial, territorial conquest. They stopped dreaming of eliminating one another. Instead, the continent that had been the source of the two worst wars the world had ever known created the European Union, an organization designed to find negotiated solutions to conflicts and promote cooperation, commerce, and trade. Because of Europe’s metamorphosis—and especially because of the extraordinary transformation of Germany from a Nazi dictatorship into the engine of the continent’s integration and prosperity—Europeans and Americans alike believed that they had created a set of rules that would preserve peace not only on their own continents, but eventually in the whole world.

This liberal world order relied on the mantra of “Never again.” Never again would there be genocide. Never again would large nations erase smaller nations from the map. Never again would we be taken in by dictators who used the language of mass murder. At least in Europe, we would know how to react when we heard it.

But while we were happily living under the illusion that “Never again” meant something real, the leaders of Russia, owners of the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, were reconstructing an army and a propaganda machine designed to facilitate mass murder, as well as a mafia state controlled by a tiny number of men and bearing no resemblance to Western capitalism. For a long time—too long—the custodians of the liberal world order refused to understand these changes. They looked away when Russia “pacified” Chechnya by murdering tens of thousands of people. When Russia bombed schools and hospitals in Syria, Western leaders decided that that wasn’t their problem. When Russia invaded Ukraine the first time, they found reasons not to worry. Surely Putin would be satisfied by the annexation of Crimea. When Russia invaded Ukraine the second time, occupying part of the Donbas, they were sure he would be sensible enough to stop.

Even when the Russians, having grown rich on the kleptocracy we facilitated, bought Western politicians, funded far-right extremist movements, and ran disinformation campaigns during American and European democratic elections, the leaders of America and Europe still refused to take them seriously. It was just some posts on Facebook; so what? We didn’t believe that we were at war with Russia. We believed, instead, that we were safe and free, protected by treaties, by border guarantees, and by the norms and rules of the liberal world order.

With the third, more brutal invasion of Ukraine, the vacuity of those beliefs was revealed. The Russian president openly denied the existence of a legitimate Ukrainian state: “Russians and Ukrainians,” he said, “were one people—a single whole.” His army targeted civilians, hospitals, and schools. His policies aimed to create refugees so as to destabilize Western Europe. “Never again” was exposed as an empty slogan while a genocidal plan took shape in front of our eyes, right along the European Union’s eastern border. Other autocracies watched to see what we would do about it, for Russia is not the only nation in the world that covets its neighbors’ territory, that seeks to destroy entire populations, that has no qualms about the use of mass violence. North Korea can attack South Korea at any time, and has nuclear weapons that can hit Japan. China seeks to eliminate the Uyghurs as a distinct ethnic group, and has imperial designs on Taiwan.

We can’t turn the clock back to 1994, to see what would have happened had we heeded Lennart Meri’s warning. But we can face the future with honesty. We can name the challenges and prepare to meet them.

There is no natural liberal world order, and there are no rules without someone to enforce them. Unless democracies defend themselves together, the forces of autocracy will destroy them. I am using the word forces, in the plural, deliberately. Many American politicians would understandably prefer to focus on the long-term competition with China. But as long as Russia is ruled by Putin, then Russia is at war with us too. So are Belarus, North Korea, Venezuela, Iran, Nicaragua, Hungary, and potentially many others. We might not want to compete with them, or even care very much about them. But they care about us. They understand that the language of democracy, anti-corruption, and justice is dangerous to their form of autocratic power—and they know that that language originates in the democratic world, our world.

This fight is not theoretical. It requires armies, strategies, weapons, and long-term plans. It requires much closer allied cooperation, not only in Europe but in the Pacific, Africa, and Latin America. NATO can no longer operate as if it might someday be required to defend itself; it needs to start operating as it did during the Cold War, on the assumption that an invasion could happen at any time. Germany’s decision to raise defense spending by 100 billion euros is a good start; so is Denmark’s declaration that it too will boost defense spending. But deeper military and intelligence coordination might require new institutions—perhaps a voluntary European Legion, connected to the European Union, or a Baltic alliance that includes Sweden and Finland—and different thinking about where and how we invest in European and Pacific defense.

If we don’t have any means to deliver our messages to the autocratic world, then no one will hear them. Much as we assembled the Department of Homeland Security out of disparate agencies after 9/11, we now need to pull together the disparate parts of the U.S. government that think about communication, not to do propaganda but to reach more people around the world with better information and to stop autocracies from distorting that knowledge. Why haven’t we built a Russian-language television station to compete with Putin’s propaganda? Why can’t we produce more programming in Mandarin—or Uyghur? Our foreign-language broadcasters—Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Radio Free Asia, Radio Martí in Cuba—need not only money for programming but a major investment in research. We know very little about Russian audiences—what they read, what they might be eager to learn.

Funding for education and culture needs rethinking too. Shouldn’t there be a Russian-language university, in Vilnius or Warsaw, to house all the intellectuals and thinkers who have just left Moscow? Don’t we need to spend more on education in Arabic, Hindi, Persian? So much of what passes for cultural diplomacy runs on autopilot. Programs should be recast for a different era, one in which, though the world is more knowable than ever before, dictatorships seek to hide that knowledge from their citizens.

Trading with autocrats promotes autocracy, not democracy. Congress has made some progress in recent months in the fight against global kleptocracy, and the Biden administration was right to put the fight against corruption at the heart of its political strategy. But we can go much further, because there is no reason for any company, property, or trust ever to be held anonymously. Every U.S. state, and every democratic country, should immediately make all ownership transparent. Tax havens should be illegal. The only people who need to keep their houses, businesses, and income secret are crooks and tax cheats.

We need a dramatic and profound shift in our energy consumption, and not only because of climate change. The billions of dollars we have sent to Russia, Iran, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia have promoted some of the worst and most corrupt dictators in the world. The transition from oil and gas to other energy sources needs to happen with far greater speed and decisiveness. Every dollar spent on Russian oil helps fund the artillery that fires on Ukrainian civilians.

Take democracy seriously. Teach it, debate it, improve it, defend it. Maybe there is no natural liberal world order, but there are liberal societies, open and free countries that offer a better chance for people to live useful lives than closed dictatorships do. They are hardly perfect; our own has deep flaws, profound divisions, terrible historical scars. But that’s all the more reason to defend and protect them. Few of them have existed across human history; many have existed for a time and then failed. They can be destroyed from the outside, but from the inside, too, by divisions and demagogues.

Perhaps, in the aftermath of this crisis, we can learn something from the Ukrainians. For decades now, we’ve been fighting a culture war between liberal values on the one hand and muscular forms of patriotism on the other. The Ukrainians are showing us a way to have both. As soon as the attacks began, they overcame their many political divisions, which are no less bitter than ours, and they picked up weapons to fight for their sovereignty and their democracy. They demonstrated that it is possible to be a patriot and a believer in an open society, that a democracy can be stronger and fiercer than its opponents. Precisely because there is no liberal world order, no norms and no rules, we must fight ferociously for the values and the hopes of liberalism if we want our open societies to continue to exist.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes

Photo

Against the Persians and Hellas

Thracian kingdoms waged wars against the Persians and Hellas for centuries. But the powerful Macedonian state of Philip II managed to crash them. It was his son, Alexander the Great, who quickly appreciated the military virtues of the Thracians and let them join the multilingual Macedonian army. After his death in 323 B. C. the Thracian king Seuth III succeeded to restore partially the former state and so the walls of the new capital city of Seuthopolis rose close to the location of present-day Bulgarian town of Kazanluk.

During the 3rd century B.C. the Romans managed to conquer the ancient Thracian lands. Later, in 74 B. C., a slave of Thracian origin who ‘graduated’ a gladiator school and became famous under the name of Spartacus headed the most continuous and mass insurrection in ancient Rome. That was the period of the so called Romanization of the Thracian world which continued until the 4th century A. D. when “The Great Migration of Peoples” began and the Thracians had to keep Celts, Huns, Goths, Avars and other barbarian tribes from invading their lands. In these circumstances the Thracians – partially Hellenized and Romanized, and having their rich and complex cultural heritage – had to stand before one of the most significant historical events for them: the disintegration of the Roman Empire in 395. In less than a century its western half was put to a collapse under the ravaging barbarian tribes from the north but the eastern part survived under the name of Byzantium with Constantinople as a capital city. Those were the days when the founders of the First Bulgarian Kingdom stepped Private Tours Balkan onto their future land…

Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians

During the 4lh to 7lh centuries the Slavs were the most multitudinous peoples in Europe.

They belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family and historians classify them usually in three main divisions: West Slavs include Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and the Wends who lived in Germany east of the river Elbe; East Slavs include Great Russians,

Little Russians (Ukrainians) and White Russians (Belorussians);

South Slavs include Serbs

Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Originally the Slavs inhabited the lands to the north of the Carpathian Mountains but by the beginning of the 6th century Slavic tribes undertook marches to the south and crossed the Danube to loot in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. At that time a tribe of Tatar nomads, the Avars, established a kingdom (407- 653) in central Asia. In 558 they crossed the Urals and settled in Dacia after which started threatening the western countries and, of course, Constantinople. The Avars forced some of the Slavic tribes to settle permanently in various regions of the Balkan Peninsula. So were differentiated the “Bulgarian group” – which stayed in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia – and the Serbo-Croatian group which gradually withdrew to the western half of the peninsula.

0 notes