#and also because he’s basically filipino john wick

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

what are your oc's aesthetics? :>

ty for asking!! here are moodboards based off of the three vtm ocs i play as with a short summary of them too !

FLORANTE ; vengeance driven banu haqim deep in mourning, trying to find the people that killed his family — a father grieving the loss of a life that kept him genuinely happy

ÙLFR ; a diableristic gangrel reawoken from torpor getting used to having more rage within them and also a loss of much of their strength due to almost being diablerized themselves

V PENG ; ventrue private investigator that was supposed to help find who were killing kindred in new york circa 2019, is slowly hunting down society of leopold members after they killed her touchstone

if you didn’t notice it but all of them are filled with rage ! ^w^

#feel free to ask about any of these three bc i love them all :P#i dont talk about florante much because i would need to delve into filipino culture alot#and also because he’s basically filipino john wick#if you notice there’s two ocs based off john wick specifically and a rabid dog that almost died#im the bigger john wick fan than u go shoo shoo#marquis asks#oc: florante#oc: ùlfr#<- their name is enir sometimes#oc: v peng#vtm#vampire the masquerade#vtm ocs#vtm oc#banu haqim#gangrel#ventrue#moodboard#mb

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Oz Fritz on working with Tom Waits and the making of 1999′s Mule Variations

Jacob Nielsen: Do you have phases with bands?

Oz Fritz: I listen to the music I grew up with all the time when I'm driving. I make mix CDs, so I have about 50 mix CDs and Dylan is definitely fairly prominent. When I first heard "Like A Rolling Stone" I had a religious experience. I kinda stopped following him when he did the Frank Sinatra songs. I didn't get that. Some of the bootlegs, the production sounds better to me than the actual album because the songs are not overly produced. A lot of his albums have terrible production. That's one thing.

JN: What do you mean?

OF: It could mean kind of a number of different things, but just that there's no excitement in the track or it obviously sounds like a drum machine. There's no real qualifier I could say that makes it sound "not good" to me. For Dylan's whole style - if you've read about how he records, he likes to record really fast and sometimes that doesn't translate. Some of his other, later stuff, is produced really well. Like "Love and Theft" and the one after that.

JN: Was it Time Out of Mind?

OF: Time Out of Mind is a classic. Although, that one gets to sound a bit dated at times. But yeah, that's a very good production. Actually, getting back to Tom Waits...that [album] very much inspired Tom Waits. And from what I've heard, and what I'm told, Dylan was inspired by Tom Waits.

JN: Those are two big personalities.

OF: And then there was the fact that right around then, when Dylan was touring he always had a bullet mic. A bullet mic is a kind of a green, specialty mic made by Shure that's specifically for harmonica. Plugging a mic like that directly into an amp gets that distorted sound. Tom kind of used it as part of his lo-fi aesthetic. That was a mic he would sing into to get a lo-fi version of a vocal. And so Dylan toured with that. Besides a regular mic, he had this bullet mic which, according to Tom, he never used but it was there.

I know Tom was influenced by Time Out of Mind because the next record we did was a record Tom produced from John Hammond Jr. called Wicked Grin and he hired the same keyboard player that had been on Time Out of Mind. His name is Augie Meyers. He's an old veteran musician from Texas. Tom put together the whole band for that album and Augie Meyers was included because of his work on Time Out of Mind.

When I was working with Tom [beginning with Mule Variations], he was constantly telling me influences and things like that. There was a constant flow of information. I know that Time Out of Mind wasn't on his radar at that point.

JN: What were the reference tracks like for Mule Variations. Would Tom say, you know, I want "Hold On" to sound like this Rod Stewart song?

OF: No he wouldn't be that specific. Before we started, he wanted me to listen to the Radiohead album that had just come out. He wouldn't say why or what specifically about it I should hear. Just a general aesthetic I guess.

JN: Bands like Radiohead don't seem very "on brand" for a guy like Tom Waits.

OF: Oh man. He stays really on top of what is happening. He told me about The White Stripes before anyone had ever heard of 'em. I think another one might have been The Strokes. He stays pretty involved.

At some point near the end [of the Mule Variations sessions] he and Kathleen went to a Bjork concert. He was extremely impressed by her turntablist, who wasn’t just scratching but playing samples from records. That caused Tom to find a DJ and bring him in and have him throw some stuff down.

JN: Right. There are samples on ‘Big In Japan’, right? What was that like in the studio?

OF: He’s constantly recording stuff. Back then, it was on cassette. I was just given a loop. Primus was doing the music for that and so he just played the loop and they played the song. It was longer, too. He edited some of the lyrics out. It got to be a little bit long, he decided.

JN: Mule Variations is 16 songs, but it was meant to be 25. So that’s a double album. What songs were cut from the album?

OF: There’s one called “Lost at the Bottom of the World,” which is on Orphans, and there’s one that’s never made it anywhere and it’s actually one of my favorite songs of his. It’s called “Always Keep a Diamond in Your Mind”. We recorded [Always Keep a Diamond in Your Mind] for Mule Variations and we recorded a different version for Alice. It did find life. Solomon Burke put it on one of his records. I didn’t think he did justice to the song. I love Tom’s versions way more. Those are the only ones I remember off hand.

JN: Years ago, you had told me that the album was called Mule Variations because of all the different versions of “Get Behind the Mule”.

OF: That’s right.

JN: Was that similar for songs like “Always Keep a Diamond in Your Mind”? Did he record that song a bunch of different ways, too?

OF: No we only had one...or maybe two different versions. I don’t remember. He worked on it. It was definitely a song in contention [for the record]. He obviously loved the song enough to put it down again on the next albums [Alice and Blood Money]. I don’t know what went in his process on not putting it on the record. That is something he has in common with Dylan that I’ve found. Some of Dylan’s best songs, he’s not put on record. There’s one called Blind Willie McTell. Some consider it one of his best songs.

Marc Ribot once told me (and this is just people’s theories and opinions) that Tom is wary of power. If something sounds too powerful, it turns him off.

JN: I wonder about his definition of power. I hear a song like “Come On Up to the House” or “Anywhere I Lay My Head” and I’m like holy shit. Tom has this amazing ability to sound like someone who is just totally broken. To me that’s very powerful.

OF: Well, Marc could have been coming from the point of view of his guitar playing. We did a whole week of Ribot doing overdubs, and I love his guitar playing. At the end of it I told him that and Marc’s comment was “well...we’ll see how much of it is used.” So I think Marc might have found stuff that was really powerful in his guitar playing and it didn’t make it on to the records.

JN: What can you recall about some of the equipment that was used on the album?

OF: So the first record that Tom did at Prairie Sun was Bone Machine. At that point, there was no “Waits Room,” there was nothing done in those lower rooms. There was only the tracking room - Studio B - and then there was the mixing room - Studio A. Studio B, the live room, sounded good but it was very generic sounding. So they started this record [Bone Machine] and they had him all set up. After one playback, Tom just hated it. He hated the sound. It lacked character, for him. So he wasn’t going to do the record there. He then had the idea to do it at his house. He rented a whole bunch of mics and mic-pres, took it to his house with engineers, but apparently it also didn’t work there. So he came back to Prairie Sun and they were just walking down that driveway. Tom was trying to think of what to do and he looked over and saw that building that has the Waits Room in it. He went in. It was a storage room and he said “well, what would this room be like if we took all the junk out of it?” So they did and it sounded amazing. So the Waits Room was actually born during the making of Bone Machine.

So for Mule Variations, which was now eight years later, he came back and he wanted to do it in that same room. This time he took over that whole floor. At that point there was no mixing board there. No control room either. It wasn’t its own studio. The control room was upstairs in Studio B. There were lines that ran from the basement [Studio C] to the upstairs [Studio B]. It was really physically hard. To adjust a mic, I’d have to run down the hill, adjust the mic, and run up the hill. We set up playback down there so they could listen back without having to come up to the control room. That whole floor was utilized for the recording. There were two rooms: the Waits Room and the Corn Room. The Corn Room is a much bigger room. [We tracked] between those two spaces, but sometimes we used the middle part of the studio.

So Tom would be playing in the Waits Room, he’d either be playing a guitar or piano, and he would be singing. This was basically his modus operandi for almost all of the songs, or maybe all of them: he would record his basic part first and then add stuff on. A lot of the songs, like Get Behind the Mule, would just be him, another piano/rhythm guitar, Larry Taylor (an upright bass player), and then a guy usually doing hand percussion. Occasionally, like for Filipino Box Spring Hog, drums would be set up outside the Waits Room. The door would be open so they would all have sight line and feel like they were in the same room.

As far as the equipment, he’s still all analog and analog approach. The recorder was a suitor 880 and all the mic pres were on that Neve desk upstairs [in Studio B]. This was in ‘98 or ‘99, I think maybe ‘98. Pro Tools had just come out, and Tom likes to check out new technology. Like I said, he likes to stay on top of things.

There’s a long story about how Jacquire King got involved. I went and interviewed with Tom to do the record and then Tom kept delaying the start time. I had a bunch of dates already booked with Bill Laswell to do live sound in the summer, which I wasn’t going to give up because he’s a long term client and friend of mine. So I told Tom when they finally got the start date “there’s gonna be some days I’m not gonna be here because I’ve got to go overseas.” Tom said “Well, you know I don’t want to keep switching engineers. You know, I really love your vibe. We’ll probably do something in the future, but I want to have one engineer for the whole thing.” So, cool. Whatever. He went looking for another engineer and he’d heard about Jacquire King. They brought him up to Prairie Sun for the interview. Tom’s interview consists of a session. He doesn’t tell you when you’re going for the interview. When you get there he says, “Okay, let’s do some recording.” They did that for Jacquire and Jacquire was not experienced with analog recording at the time. They didn’t like his recording. They tried a thing in the Waits room and it just didn’t work out. So I got a call the next week from Tom, saying that he and Kathleen both like Jacquire but they realized he didn’t really have his chops up yet on analog recording. So...would I be willing to be the chief recording engineer? [I’d] set the parameters, meet with Jacquire, and show him how I do analog recording. The thing Tom liked about Jacquire was he was a Pro Tools engineer. So Jacquire became more than just a substitute for me. He brought out Pro Tools and they used it on FIlipino Box Spring Hog. Lowside of the Road might have been mixed [on Pro Tools] too.

JN: What is the difference in mixing on Pro Tools vs. Analog?

OF: At that point, I don’t think they were using Pro Tools in the box, which means to completely mix something in the computer, strictly digital. It doesn't go to a mixing desk or any other gear outside the computer. They were using Pro Tools as the source instead of a tape machine. The reason they were using Pro Tools was because he was kind of cutting and pasting stuff and moving stuff around. Which is a lot harder to do with tape.

I would say the whole record is maybe 80 or 90 percent analog. Even the Pro Tools stuff wasn’t mixed in Pro Tools. It went out, back through the Neve and then mixed to analog tape.

JN: On a song like Lowside of the Road, the beginning sounds like a man snoring. Is that a vibraslap making that sound?

OF: That song had its genesis somewhere else. It came from an 8 track tape that he had. I think he recorded it at his house. That’s where the basic tracks were. They brought that into Prairie Sun and they overdubbed on top of that. I’m not sure how it started.

JN: On Mule Variations there are a lot of these images that are “painted” with sound. Was that sort of stuff a directive to you? Did Tom say “Oz, I want this to sound like a guy snoring.”?

OF: Nothing was ever that specific. But the visuals, when you say “painted,” that’s very accurate. He wouldn’t say “make it sound like a guy’s snoring,” but when I was mixing or overdubbing Cold Water, he said he wanted more brown in the mix. Which I knew. I could relate that to a particular range or frequencies.

When we were mixing Alice, he’d give these real abstract images. He said, “Oz. Picture yourself in a dollhouse. You’re in a dollhouse. You’re in a room in a dollhouse and a regular size person comes in and sticks their face into the dollhouse. That’s how I want my vocal to sound.”

JN: That seems pretty on brand for Tom Waits. Is that pretty unique in comparison to other artists you’ve worked with?

OF: It’s totally unique. No one else has come close to being like that in terms of direction. Bill Laswell once told me when we were working on a dub record and he told me I should reference a book called Naked Lunch by William Burroughs. That’s the only thing that comes close.

There was a more traditional reference that came from Tom too. There’s a drummer named Andrew Borger, who’s on the record. He had made a tape, a cassette, of him playing drums. It was like an audition tape. And it was slightly overloaded. It had a particular sound, which Tom loved. He brought me that cassette tape and told me to emulate that sound. Man, it was really hard. I got a great sound, I thought. It’s the drum sound for Filipino Box Spring Hog. It’s much different than the cassette tape but that was my attempt to get that reference.

JN: Tom is someone who’s very famous for his different voices. Songs like Pony and Cold Water are great examples of his range. Tell me about recording his different voices.

OF: They were all the same microphone, those two particular songs. There wasn’t a lot of variation on microphones. There was a lot of processing done in the mixing to try to sculpt the vocal sound. In Get Behind the Mule, he’s singing through a PVC pipe. That was the same microphone, but obviously it sounds way different because he’s singing through a pipe. That was completely his decision to do that.

There was one time though, there was a session on the Blood Money album, where he was trying to get this song and he just couldn’t get it. I suggested to him to try a real lo-fi mic. He did and that’s how he got the vocal. That was a bit of an exception. Generally, it was always kind of the same mic that he sang into.

Tom wanted to record Chocolate Jesus outside. He set everyone up in front of those white doors that are in front of the Waits Room. Jacquire mic’d everything up. When Tom heard it he thought it sounded too nice. Too high fidelity. So Jacquire went back. He took down all his close mics, put up a pair of shotgun mics, and recorded the whole ensemble just with these shotgun mics. I technically mixed that song but there wasn’t much to do because there were only two channels.

JN: That’s another song that really paints a picture with sound. That recording feels like a hot summer day in the Deep South. Tom sounds exhausted, almost like a sharecropper.

OF: Right.

JN: You don’t seek out a production credit on albums you work on, do you?

OF: Right. There’s no producer. There’s a reducer.

JN: It sounds to me like Tom seeks out people that will help him shape the sounds that he has, not vice versa.

OF: Yeah. You’ve got to sort of realize your place though, too. He never told me this, I was trained this way in New York...the artist is the boss. I’m doing their record. I’m not doing my record. The only creative stuff I felt free to do was on the technical side. Nowadays you have a lot of musicians who do their own engineering, so they’ll start giving you engineering suggestions. Stuff like what mics to use or even how to place them. Which is fine, but Tom never went near that at all. One time he wanted me to hear the sound of a whip on a cassette in the back of his SUV that was cranked incredibly fucking loud [laughs]. He would just try to give you references to try to go for.

[In Listen Up!] there’s a chapter about working with Tom Waits. He talks about giving these ideas to Tom and Kathleen. He’d come up with these sounds or whatever, you know, “check this out, let’s use it!” type of thing. At one point he talks about how Tom called him up at the hotel, and if you read the book you’ll get a lot of very colorful imagery of Tom basically saying “back the fuck off,” but he says it much more politely.

Some other input I got was, Tom was very influenced by this turntable DJ that Bjork had, and so he brought a guy in [to do that]. He was also very interested in samples. I had a sound effects library and I brought that in and we used some of the effects off of that.

My sound effects library was on these things called DATs (Digital Audio Tapes). They were the same quality as recordable CDs. During the 90s, I was living sort of bi-costally. All of my work was back in New York and most of my work was with Bill Laswell at his Greenpoint studio in Brooklyn. Above his studio, I had converted it into an art gallery and I used to stay above the studio. I had a lot of time. I basically dubbed all of Bill’s CD sound effects and put them on DATs. [During Mule Variations], I’d bring the whole thing in. We put an auctioneer on Eyeball Kid. Tom would just come up with ideas and we would just go through [my DATs] and choose one.

JN: The first track that comes to mind with something like your library is “What’s He Building?” Did you rely on your sound effects library when you were tracking that song?

OF: Well, that was a pretty unique recording. He did three or four takes of that song, but there was no overdubs added afterwards. Everything was completely live. It’s that big room, The Corn Room, at Prairie Sun. Tom brought any musical instrument that he had at his house, he brought to Prairie Sun. That whole floor was just tons of instruments. He had all this home-made percussion. The kind that Harry Parch would make. So there was all kinds of instruments like that in the Corn Room and he just started doing the vocal, the spoken word on a handheld mic. An SM7 or something like that. Then Kathleen and the assistant engineer at the time, Jeff Sloan (who was also a percussionist), made the background sounds. All the background sounds are them hitting stuff just kind of randomly while Tom’s doing the spoken word. Some of the sounds are from the harp of a piano just being hit. That was all done live, but he edited some of it out. There were a lot more verses.

JN: Really?

OF: Oh yeah. The guy was definitely building something in there.

JN: This album was recorded at the peak of the CD boom in the music industry. A lot of people, at least at Tom Waits’ calibur, were recording digitally. Is there any insight as to why Tom kind of insisted on doing things analog?

OF: At Prairie Sun back then, there were no Pro Tools and that was how you recorded there. At my interview with Tom, I told him I had been listening to Bone Machine and I really liked the sound of it.

He said “No, don’t use that as a reference. You should be listening to Rain Dogs. That’s the one I want to use as a reference for my recordings.”

It just so happened that I knew the difference in the recording between Bone Machine and Rain Dogs. [Robert Musso], who recorded Rain Dogs, was one of my engineer teachers in New York. I knew that they did it by the New York standard, which is 30 inches per second for the tape speed, no noise reduction. I knew that Bone Machine had been recorded in California at 15 ips, half the speed and using noise reduction. The difference in those techniques is that, when you use noise reduction, you can’t slam the tape. You can’t hit the tape hard. Part of the whole New York aesthetic was...record at 30 ips, hit the tape as hard as you can without blowing things up and you get a thing called tape compression. That’s partly what makes things sound that punchy. That’s part of why Mule Variations has a bigger, more open sound. Whereas, with Bone Machine - which I love the sound of [and] I think Tchad Blake did a really excellent job mixing it - sounds a little tighter or closed.

JN: What do you mean when you say “hit the tape”?

OF: Record at a hot level, so your drums [for example] are hitting your VU meters. They’re slamming it. When people say they love the sound of tape, a lot of that is recording it to its maximum headroom. You don’t get quite the same effect when you’re doing it at 15 ips and using noise reduction. Noise reduction is severely processing the sound. Partly, the reason why records from the 50s and 60s and 70s sound bigger was the whole philosophy was using as little electronics as possible. To go as much as you could directly from the mic to the tape recorder and have as few electronics in between as possible. So that was kind of the aesthetic brought to Mule Variations. As much as possible, direct to the tape machine. With Dolby noise reduction, it’s encoding the sound when it goes into the tape machine and then decoding the sound when it comes out. That’s how it’s taking out the noise, but it’s being processed. [The sound] doesn’t go through that stage if you’re not using noise reduction. If you’re not using noise reduction, you’re almost obliged to record at a loud level because when you record at a louder level, you’re not going to get as much noise.

JN: Did Tom know that you had studied under Robert Musso?

OF: No. I told him at the interview, but he hadn’t known that prior. He did check me out a little bit. When he called me the very first time and he asked for a sample of my mixes, he called them “hyper real.” They were too big, or maybe too powerful for him. I think part of it was that he needed a professional engineer that was in the area. I’d been recommended to him by Brain, the drummer for Primus. I knew Brain from New York. The thing that Tom was super impressed with was, I sent him a tape of my ambient recording. Stuff that I had done out on the street. Interesting things. Just sounds. He liked that more than my actual mix reel.

JN: How do you approach miking a room like the Corn Room?

OF: Well, I always had room mics. I had two U87s up in the corners of the Waits room along with all the close mics. It’s just a matter of putting up extra mics, having ambient mics. For a drum track, I use four sets of ambient mics. Two for the whole room, to get the biggest room [sound] as possible. Two that I call boom mics. They’re not close mics, but they’re not real distant so they’re like if a person was just standing in front of a drum kit.

This was an educational experience for me too. I never worked on anything like Tom Waits. I’m writing a book - my memoir about the music industry. Part of what I say in there is, when I was in New York, I learned how to make things sound as big and powerful as possible. We went to extra lengths to push the boundaries. Coming out and working with Tom Waits, that was a whole different aesthetic. He didn’t want it to sound as big, beautiful, and shiny as possible. [His] whole lo-fi aesthetic was a huge educational part of my recording career.

Years ago, you told me that the initial mix of Hold On had these beautiful guitar arpeggios. Then Tom comes to you and says “Oz, some guy like Rod Stewart is going to come along and cover this song,” and so he didn’t want it to sound too pretty. How many other times did he come back and say “it sounds too good”?

That was really the only time. Mixing was challenging, definitely. We finished tracking and we moved from the tracking room at Prairie Sun to the mix room, which had a different board and was configured differently back then. We spent a week there, mixing. He would always love the sound of it when he was hearing it in the control room. We’d make a cassette for him but he’d listen at home and he wasn’t digging the mixes at all. It was getting to be every single day that was happening. So I was getting kind of nervous. Like, at what point am I going to get fired?

We decided that what he didn’t really like was the sound of that board. It was a Trident board. It did have a much different sound than the Neve board. We were constantly making rough mixes. He really dug the sound of the rough mixes done in the Neve room [Studio B]. So the whole thing was…”Okay, after this week we’re going back into Studio B to mix on the Neve.” But there was one day, a Friday, when we mixed Big in Japan [on the Trident board]. At that point it had been four or five days of not really hearing anything he liked when he got home. He said “okay, give me a cassette.” He wasn’t even that thrilled with what was happening. I made him a cassette of Big in Japan and he brought it home and he just loved it. He loved the mix. All he said was he wanted the edits put back in. The tape that had been edited out was on the floor, so I had to go and dig through all these pieces of tape, find the right piece and put it back into the song. That was the mix.

In terms of the mixing...it was a long process. He had me and Jacquire each do our own versions of mixes. I think Jacquire has three on there, or two of ‘em, from Pro Tools and then I have the rest. Most of the mixes I did, that he accepted, four or five of them were done in one night. He gets into this thing where he likes to work really fast. He doesn’t want people thinking too much. Just working on instinct. I think it was the night of Hold On that we were on a roll and did four or five songs. Eyeball Kid was mixed that night, then Come On Up to the House.

Alice was done the same way too. He always worked Monday to Friday and took weekends off. On a Friday he walks in and says “Okay, Oz. Let’s do some mixing.” I started mixing some songs and I think we mixed three or four, just knocked them off. He loved it. He said “Well Oz, we’re on a roll. Can you stay over and work tomorrow?” Okay, sure. I worked on Saturday and I think we mixed maybe 90% of the album in those two days. That’s after trying mixes, you know, regular. Spending a whole day on a song.

JN: How many other people work like that?

OF: Well...no one. Bill Laswell to some extent, also works really fast. People have that recognition when something is happening, and they know when to stop and not to take it too far. Tom’s like that. He’s always trying to keep it alive and fresh and not too overly worked.

[Working on Mule Variations], you didn’t know exactly what you were going to do every day. You might be thinking, okay, we’ve got all the songs done. We’re going to do overdubs today. And then he’d say, “I’ve got a new song.” It was always very Zen in the sense of...you had to pay attention to what was going on.

JN: What new songs did he come in with?

OF: There’s one on Orphans. Rain On Me, I think it’s called. That was one where, I think we were mixing and he’s like “okay, I’ve got a new song. I want to record this.”

On Blood Money and Alice, three of the mixes were just complete rough mixes. Two of them were from [when] we recorded everything live and then the band would come in for a playback. I would run the playback into a DAT, which was CD quality. Just to hear the monitor mix. Two of those mixes were the first time anybody had ever heard it on tape, including myself. That’s just my balance going to the recorder.

JN: What songs were those?

OF: I’m bad with titles. Something about King Edward’s Brother. I don’t remember the other one, but the very first song on Blood Money is the rough mix.

That’s a very interesting story, too. 9/11 happened while we had some time off. The first session that we had was about a week after it happened. Tom said he was thinking about cancelling it, but if he did he would just be sitting in front of the TV getting more depressed, so we did the session. The mood was...you just feel his mood. He just projects it. Not that he’s intentionally being negative or whatever, but if he’s not in a good mood, you kind of just feel it. He came in, the mood was really heavy and says “I want to put a hand drum on Misery’s the River of the World and then I want you to give it a good rough mix.” Meaning I got to spend more than 15 minutes getting a balance. I spent two or three hours getting a decent rough mix. When it came time to mix those records, he was very concerned that those two albums were going to sound the same because they were all done in the same studio with the same musicians and the same production team. So he brought this other engineer up from LA to mix Blood Money. They did about three or four mixes of Misery is the River of the World, but he always went back and he ended up using that rough mix. I think it’s not because it’s such a brilliant mix but because there was something about the mood in the studio at the time. If you listen to the song, it’s kind of appropriate for a 9/11 aftermoment.

JN: What do you remember about the album’s release?

OF: Even though CDs were prevalent, everything inside the studio was an analog world. Like, I didn’t know how to use Pro Tools. It wasn’t a common thing. From what I remember, everyone always did both. Major releases still pressed to vinyl and CD.

Tom loved all the songs that we had but there were too many of them. He had hoped to make it a double album, but the record company was shy about that because it was his first record on Epitaph. They felt like it was much harder to market a double album. Some of the songs that were chosen were at the mastering session. It went up to that last minute. I really loved Lowside of the Road, which I was less involved with. I really lobbied hard for that to be on the record. It came close to not being on the record.

1 note

·

View note

Link

"A fight scene can’t be just kill, kill, kill...You're telling a story."

Jeremy Price

May 17, 2019

John Wick

Not everyone appreciates the subtleties of ramming a pencil through an eardrum. Jonathan Eusebio does.

“A fight scene can’t be just kill, kill, kill,” he says. “There’s a rhythm, an emotional arc to it. You’re telling a story.”

Eusebio is a core part of 87eleven Action Design, the team of martial arts virtuosos behind the John Wick films. With director (and black belt) Chad Stahelski at the wheel, 87eleven has crafted an action series that masterfully combines the balletic elegance of The Matrix with the gut-wrenching savagery of Fight Club.

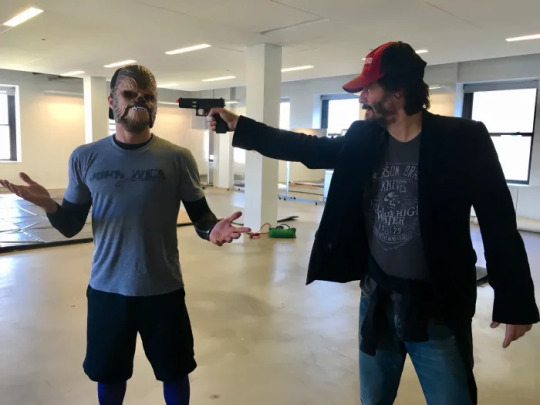

Keanu Reeves stunt double Jackson Spidell in Chewbacca mask and Keanu Reeves

Jackson Spidell

It’s an aesthetic of violence that’s truly in a class of its own—brutal, beautiful, and undeniably badass.

So with John Wick: Chapter 3—Parabellum hitting theaters today, Maxim reached out to the stunt professionals behind the series to find out how they train for and execute some of the most daring stunts and combat sequences ever captured on film.

Jackson Spidell, stunt double for Keanu Reeves in all three 'John Wick' movies

Keanu Reeves and Jackson Spidell - Jackson Spidell

At the beginning of John Wick: Chapter 2, John gets hit by a car. What was it like to execute that stunt?

We in the stunt business have a funny saying, kind of a running joke. We say, “Well, gotta pay this rent”—and then we just go for it.

For this one, Chad [Stahelski] wanted the hit to be as blind as possible. He was like, “I understand if you have to look right before it hits you—just don’t react too early.” And I was like, “Okay, I’m not looking at that car at all.”

The car was driven by Danny Hernandez, one of my teammates. I was the first person he'd ever hit with a car on film, so we're getting ready, and he's like, “You good?” I was like, “Dude, just put that fucking gas pedal down.” We bump fists, give each other hugs, and slap each other in the face.

Jackson Spidell (top) Oleg Prudius (holding Spidell over his head)

Jackson Spidell

[So we go to film it.] I was looking at the person in front of me, using my peripherals, and then—bam!—got cleaned out. Danny was kinda booking it, probably going 15 to 17 miles an hour. I ride the hood, he brakes, I roll off... and they’re like, “Cool. Moving on.”

The funniest thing about that take was that there was a huge stunt pad in the back of the shot that someone forgot to move. Chad was like, “The take is too good... We’ll have to paint it out.” He goes, “Someone [just made] a multi-thousand-dollar mistake. Thanks for that.” And I was like, “Well, I'm gonna have to thank the visual effects department for making it so that I don't have to get hit by a car again!”

Jonathan Eusebio, fight coordinator for 'John Wick' and 'John Wick: Chapter 2', stunt coordinator and fight choreographer for 'John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum'

Jonathan Eusebio (left) training Keanu (in beanie) - Jonathan Eusebio

What was it like to train Keanu for his role as John Wick?

He’s an absolute workhorse. Usually, we take like eight weeks to train for a movie. But he’ll train eight hours a day for like six months. It’s amazing. He’s over 50, and he can do things that some stunt guys can’t do.

If you watch Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, or Bruce Lee fights, it’s all long, beautiful shots—you can see all the choreography, and that’s because they can physically do all those moves. Sometimes you have to cheat if [actors] can't do the stuff—[the camera] goes to a close-up, or to the back of the double. But there’s no reason to turn the camera away from Keanu, because he does 98% of everything—and the other 2% are things that insurance won’t let us do.

As for the martial arts training, we made judo and jiu-jitsu his base styles. For his empty-hand stuff, we used a lot of karate-based blocks and strikes. We were also using sambo and shoot wrestling, and then the knife stuff—and the pencil stuff—was from our training in kali, a Filipino style.

In this new movie, John is fighting many different types of opponents. Chad [Stahelski] wanted to see his judo and jiu-jitsu versus kung fu, versus karate, and versus silat. So the [question] was always, how does someone with that skill set deal with these other, equally lethal skill sets?

In the first [two movies,] John was mostly fighting one-on-one, but this time he's fighting multiple opponents at the same time. So we also used a lot of aikido-esque movements—a lot of circular movements and wrist locks, not as much striking. There’s a lot of absorbing force and redirecting it, so the footwork and evasion tactics are very smooth.

At the end of the day, fight choreography and dance choreography are all the same. You have movements that have to be matched by both partners—it’s a dialogue, a whole visual language. So when [Keanu learns] the choreography, it’s just as important for him to get the mindset or the intention of what he’s doing, because that's what people are drawn to.

Jon Valera, fight coordinator for John Wick and John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum

Jon Valera

In Parabellum, Halle Berry’s character fights alongside combat-trained canines. How does it feel to be attacked by a dog?

So you wear this pad on your chest—almost like an impact vest—and the trainers tie this fluorescent green tug to it, which is like a chew toy. Then you stand in front of the dog, the trainer taps the tug, and these dogs, Belgian Malinois, have to lock eyes on it. But some of them zeroed in on your eyes instead, which was kind of scary. One of the dogs was named Sam, and they said he had ADD because he was always looking around everywhere. But when the dogs [are preparing to] attack, their eyes can’t wander—they have to stay locked on the tug. So if Sam started looking around, the trainer would go back to the tug. He’d go, “Sam,” tap, tap, tap, “keep your eyes here.” Now the dog is basically a missile—the [instant] you see them leave the ground is literally a second before you get hit. The trainer always told us, “When you feel the hit, go with it. Don’t stonewall or try to fight it, or you could hurt the dog.” They think of it as play, so if they get hurt, they won’t want to attack again.

Jon Valera (wearing shorts), Jonathan Eusebio (spiky hair), Jackson Spidell (gray hat).jpg - Jon Valera

The tug is tied and reinforced so that when the dog clamps down on it, he can't get it off, and it looks like he’s really ripping into us. Then once they yell “Cut,” the trainer throws a bouncy toy, and the dog goes after it. There were also groin hits, so all of us invested in steel cups. [Fortunately,] the tug for those hits was not right at the groin, but just below the beltline. And the trainer would be sitting there tapping it: “Right here, right here…” I’ve had my fair share of injuries in stunts, but for some reason my fear just turns off on set. And we had already trained with the dogs for two months, so I treated each one like just another training partner. Like, “Hey, I trust this guy.”

I’m just so proud and honored to be a part of this movie… Wait till you see it. You’re gonna be blown away.

20 notes

·

View notes