#american telephone and telegraph company

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

🇺🇸 Step back in time and delve into the fascinating history of AT&T's journey in the development and production of mobile phones! The AT&T Corporation (an abbreviation of its former name, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company) was a successor of the original Bell Telephone Company founded by the legendary inventor of the first practical telephone - Alexander Graham Bell in 1877.

👉 AT&T's division - Bell Laboratories, was created in 1925 from the consolidation of the R&D organizations of Western Electric and AT&T. Bell Labs made significant scientific advances, including the transistor, the laser, the solar cell, the digital signal processor chip, the Unix operating system, and the cellular concept of mobile telephone service.

🔍 AT&T's foray into the realm of mobile phones dates back to the early days of telecommunications. In the late 1940s, it embarked on pioneering efforts to develop mobile phone technology, laying the groundwork for future advancements in wireless communication.

💡 In the early years, AT&T, a huge telecommunications giant, focused on developing analog mobile phone systems, laying the groundwork for the future of wireless communication. Their first systems were limited to car phones, which required roughly 30 pounds of equipment in the trunk. These early devices were bulky and limited in functionality, but they represented a groundbreaking leap forward in telecommunications.

🏁 The first cellular phone was the culmination of efforts begun at AT&T Bell Labs and continued by Motorola Inc. While Motorola was developing the cellular phone itself, AT&T Bell Labs worked on the cellular system called AMPS. On April 3, 1973, Martin Cooper placed the first public call from a Motorola handheld portable cell phone to his counterpart Dr. Joel S. Engel at AT&T Bell Labs.

🏙 Advanced Mobile Phone System (AMPS) was an analog mobile phone system standard originally developed by AT&T Bell Labs and later modified in a cooperative effort with Motorola Inc. It was officially introduced in the USA on October 13, 1983. On this day, Bob Barnett, former president of Ameritech Mobile Communications, placed a call with a cell phone to the grandson of Alexander Graham Bell, who was in Germany for the event.

➡️ During the 1980s to 1990s, AT&T Corporation tried to achieve its place in the cell phone market and introduced some interesting devices: 3810, 3850, and 6650. Featuring sleek and ergonomic designs, they were a real testament to innovation and engineering excellence.

⚙️ Equipped with advanced features for its time, these phones boasted impressive functionality, including voice calling, text messaging, and address book capabilities. Their cutting-edge technology represented a leap forward in mobile communication, setting new standards for performance and reliability. These phones also ran on the AMPS 800 cell system.

📑 In 1996, AT&T spun off Bell Laboratories, along with most of its equipment manufacturing business, into a new company named Lucent Technologies. AT&T retained a small number of researchers who made up the staff of the newly created AT&T Labs. That meant the decline of future attempts at cell phone manufacturing by AT&T Corporation.

🌐 Today, AT&T continues to be a powerful multinational telecommunications holding company, offering a diverse range of cutting-edge services to consumers worldwide. With a rich legacy of innovation and a steadfast commitment to excellence, AT&T remains a leader in the ever-evolving landscape of telecommunications.

#old technology#techtime chronicles#companies#old tech#tech#technology#information technology#technews#corporations#electronics#at&t#bell labs#lucent#mobile phones#motorola inc#bell telephone company#american telephone and telegraph company#at&t corporation#cell phone#cell system#amps 800#alexander graham bell#car phone#telecomindustry#telephone#telecommunications#innovators#innovative#innovation#industry

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Traveler’s Telephone. An advertisement of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company - 1927.

#vintage advertising#vintage illustration#the bell system#american telephone and telegraph company#vintage telephones#at&t#telephones#bell telephone#ma bell

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

January 25, 1915: A historic moment connecting the two coasts of the United States via phone lines when the first transcontinental phone call was made from NYC to San Francisco. The conversation took place between Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas A. Watson who on October 9, 1876 also had the first ever telephone conversation. The first transcontinental words were uttered by Dr Bell in NYC to his colleague in San Francisco: "Mr. Watson, are you there?"

The call was made from the 15th floor of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company at 15 Dey Street (aka 195 Broadway) in the Financial District.

#FirstTranscontinentalPhoneCall #AlexanderGrahamBell #ThomasAWatson #TelephoneHistory #AmericanTelephoneandTelegraphCompany #CommunicationsHistory #NewYorkHistory #NYHistory #NYCHistory #History #Historia #Histoire #Geschichte #HistorySisco

https://www.instagram.com/p/Cn21hg1u-Nl/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#First Transcontinental Phone Call#Alexander Graham Bell#Thomas A. Watson#Telephone History#American Telephone and Telegraph Company#Communications History#New York History#NY History#NYC History#History#Historia#Histoire#Geschichte#HistorySisco

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

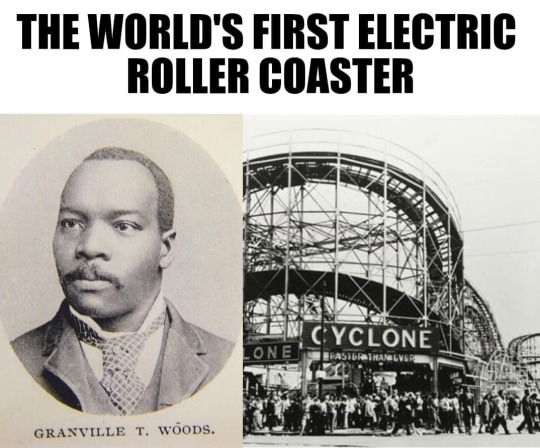

THE WORLD'S FIRST ELECTRIC ROLLER COASTER

Granville T. Woods (April 23, 1856 – January 30, 1910) introduced the “Figure Eight,” the world's first electric roller coaster, in 1892 at Coney Island Amusement Park in New York. Woods patented the invention in 1893, and in 1901, he sold it to General Electric.

Woods was an American inventor who held more than 50 patents in the United States. He was the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Self-taught, he concentrated most of his work on trains and streetcars.

In 1884, Woods received his first patent, for a steam boiler furnace, and in 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called "telegraphony", would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, he patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. Woods caught smallpox prior to patenting the technology, and Lucius Phelps patented it in 1884. In 1887, Woods used notes, sketches, and a working model of the invention to secure the patent. The invention was so successful that Woods began the Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, to market and sell his patents. However, the company quickly became devoted to invention creation until it was dissolved in 1893.

Woods often had difficulties in enjoying his success as other inventors made claims to his devices. Thomas Edison later filed a claim to the ownership of this patent, stating that he had first created a similar telegraph and that he was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself, proving that there were no other devices upon which he could have depended or relied upon to make his device. After Thomas Edison's second defeat, he decided to offer Granville Woods a position with the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

In 1888, Woods manufactured a system of overhead electric conducting lines for railroads modeled after the system pioneered by Charles van Depoele, a famed inventor who had by then installed his electric railway system in thirteen United States cities.

Following the Great Blizzard of 1888, New York City Mayor Hugh J. Grant declared that all wires, many of which powered the above-ground rail system, had to be removed and buried, emphasizing the need for an underground system. Woods's patent built upon previous third rail systems, which were used for light rails, and increased the power for use on underground trains. His system relied on wire brushes to make connections with metallic terminal heads without exposing wires by installing electrical contactor rails. Once the train car had passed over, the wires were no longer live, reducing the risk of injury. It was successfully tested in February 1892 in Coney Island on the Figure Eight Roller Coaster.

In 1896, Woods created a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters, known as the "safety dimmer", which was economical, safe, and efficient, saving 40% of electricity use.

Woods is also sometimes credited with the invention of the air brake for trains in 1904; however, George Westinghouse patented the air brake almost 40 years prior, making Woods's contribution an improvement to the invention.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Harlem Hospital in New York City on January 30, 1910, having sold a number of his devices to such companies as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Until 1975, his resting place was an unmarked grave, but historian M.A. Harris helped raise funds, persuading several of the corporations that used Woods's inventions to donate money to purchase a headstone. It was erected at St. Michael's Cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens.

LEGACY

▪Baltimore City Community College established the Granville T. Woods scholarship in memory of the inventor.

▪In 2004, the New York City Transit Authority organized an exhibition on Woods that utilized bus and train depots and an issue of four million MetroCards commemorating the inventor's achievements in pioneering the third rail.

▪In 2006, Woods was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

▪In April 2008, the corner of Stillwell and Mermaid Avenues in Coney Island was named Granville T. Woods Way.

510 notes

·

View notes

Text

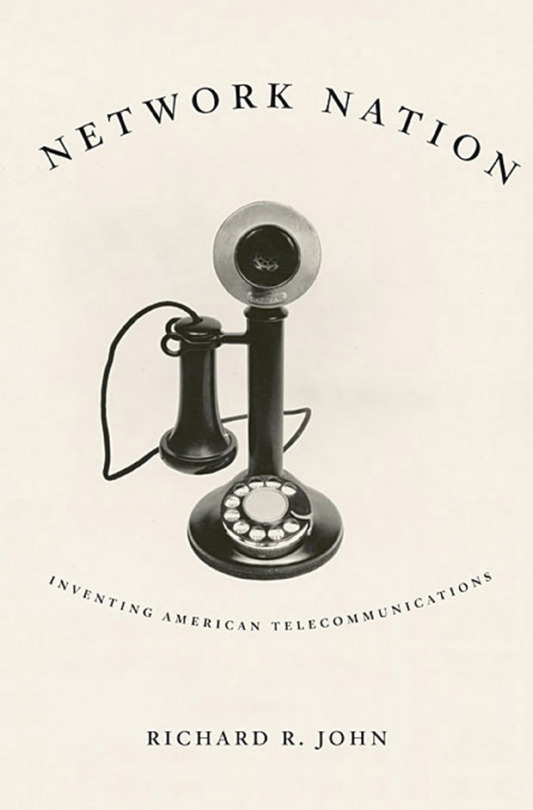

Richard R John’s “Network Nation”

THIS SATURDAY (July 20), I'm appearing in CHICAGO at Exile in Bookville.

The telegraph and the telephone have a special place in the history and future of competition and Big Tech. After all, they were the original tech monopolists. Every discussion of tech and monopoly takes place in their shadow.

Back in 2010, Tim Wu published The Master Switch, his bestselling, wildly influential history of "The Bell System" and the struggle to de-monopolize America from its first telecoms barons:

https://memex.craphound.com/2010/11/01/the-master-switch-tim-net-neutrality-wu-explains-whats-at-stake-in-the-battle-for-net-freedom/

Wu is a brilliant writer and theoretician. Best known for coining the term "Net Neutrality," Wu went on to serve in both the Obama and Biden administrations as a tech trustbuster. He accomplished much in those years. Most notably, Wu wrote the 2021 executive order on competition, laying out a 72-point program for using existing powers vested in the administrative agencies to break up corporate power and get the monopolist's boot off Americans' necks:

https://www.eff.org/de/deeplinks/2021/08/party-its-1979-og-antitrust-back-baby

The Competition EO is basically a checklist, and Biden's agency heads have been racing down it, ticking off box after box on or ahead of schedule, making meaningful technical changes in how companies are allowed to operate, each one designed to make material improvements to the lives of Americans.

A decade and a half after its initial publication, Wu's Master Switch is still considered a canonical account of how the phone monopoly was built – and dismantled.

But somewhat lost in the shadow of The Master Switch is another book, written by the accomplished telecoms historian Richard R John: "Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications," published a year after The Master Switch:

https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674088139

Network Nation flew under my radar until earlier this year, when I found myself speaking at an antitrust conference where both John and Wu were also on the bill:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2VNivXjrU3A

During John's panel – "Case Studies: AT&T & IBM" – he took a good-natured dig at Wu's book, claiming that Wu, not being an historian, had been taken in by AT&T's own self-serving lies about its history. Wu – also on the panel – didn't dispute it, either. That was enough to prick my interest. I ordered a copy of Network Nation and put it on my suitcase during my vacation earlier this month.

Network Nation is an extremely important, brilliantly researched, deep history of America's love/hate affair with not just the telephone, but also the telegraph. It is unmistakably as history book, one that aims at a definitive takedown of various neat stories about the history of American telecommunications. As Wu writes in his New Republic review of John's book:

Generally he describes the failure of competition not so much as a failure of a theory, but rather as the more concrete failure of the men running the competitors, many of whom turned out to be incompetent or unlucky. His story is more like a blow-by-blow account of why Germany lost World War II than a grand theory of why democracy is better than fascism.

https://newrepublic.com/article/88640/review-network-nation-richard-john-tim-wu

In other words, John thinks that the monopolies that emerged in the telegraph and then the telephone weren't down to grand forces that made them inevitable, but rather, to the errors made by regulators and the successful gambits of the telecoms barons. At many junctures, things could have gone another way.

So this is a very complicated story, one that uses a series of contrasts to make the point that history is contingent and owes much to a mix of random chance and the actions of flawed human beings, and not merely great economic or historical laws. For example, John contrasts the telegraph with the telephone, posing them against one another as a kind of natural experiment in different business strategies and regulatory responses.

The telegraph's early promoters, including Samuel Morse (as in "Morse code") believed that the natural way to roll out telegraph was via selling the patents to the federal government and having an agency like the post office operate it. There was a widespread view that the post office as a paragon of excellent technical management and a necessity for knitting together the large American nation. Moreover, everyone could see that when the post office partnered with private sector tech companies (like the railroads that became essential to the postal system), the private sector inevitably figured out how to gouge the American public, leading regulators to ever-more extreme measures to rein in the ripoffs.

The telegraph skated close to federalization on several occasions, but kept getting snatched back from the brink, ending up instead as a privately operated system that primarily served deep-pocketed business customers. This meant that telegraph companies were forever jostling to get the right to string wires along railroad tracks and public roads, creating a "political economy" that tried to balance out highway regulators and rail barons (or play them off against each other).

But the leaders of the telegraph companies were largely uninterested in "popularizing" the telegraph – that is, figuring out how ordinary people could use telegraphs in place of the hand-written letters that were the dominant form of long-distance communications at the time. By turning their backs on "popularization," telegraph companies largely freed themselves from municipal oversight, because they didn't need to get permission to string wires into every home in every major city.

When the telephone emerged, its inventors and investors initially conceived of it as a tool for business as well. But while the telegraph had ushered in a boom in instantaneous, long-distance communications (for example, by joining ports and distant cities where financiers bought and sold the ports' cargo), the telephone proved far more popular as a way of linking businesses within a city limits. Brokers and financiers and businesses that were only a few blocks from one another found the telephone to be vastly superior to the system of dispatching young boys to race around urban downtowns with slips bearing messages.

So from the start, the phone was much more bound up in city politics, and that only deepened with popularization, as phones worked their ways into the homes of affluent families and local merchants like druggists, who offered free phone calls to customers as a way of bringing trade through the door. That created a great number of local phone carriers, who had to fend off Bell's federally enforced patents and aldermen and city councilors who solicited bribes and favors.

To make things even more complex, municipal phone companies had to fight with other sectors that wanted to fill the skies over urban streets with their own wires: streetcar lines and electrical lines. The unregulated, breakneck race to install overhead wires led to an epidemic of electrocutions and fires, and also degraded service, with rival wires interfering with phone calls.

City politicians eventually demanded that lines be buried, creating another source of woe for telephone operators, who had to contend with private or quasi-private operators who acquired a monopoly over the "subways" – tunnels where all these wires eventually ended up.

The telegraph system and the telephone system were very different, but both tended to monopoly, often from opposite directions. Regulations that created some competition in telegraphs extinguished competition when applied to telephones. For example, Canada federalized the regulation of telephones, with the perverse effect that everyday telephone users in cities like Toronto had much less chance of influencing telephone service than Chicagoans, whose phone carrier had to keep local politicians happy.

Nominally, the Canadian Members of Parliament who oversaw Toronto's phone network were big leaguers who understood prudent regulation and were insulated from the daily corruption of municipal politics. And Chicago's aldermen were pretty goddamned corrupt. But Bell starved Toronto of phone network upgrades for years, while Chicago's gladhanding political bosses forced Chicago's phone company to build and build, until Chicago had more phone lines than all of France. Canadian MPs might have been more remote from rough-and-tumble politics, but that made them much less responsive to a random Torontonian's bitter complaint about their inability to get a phone installed.

As the Toronto/Chicago story illustrates, the fact that there were so many different approaches to phone service tried in the US and Canada gives John more opportunities to contrast different business-strategies and regulations. Again, we see how there was never one rule that governments could have used if they wanted to ensure that telecoms were well-run, widely accessible, and reasonably priced. Instead, it was always "horses for courses" – different rules to counter different circumstances and gambits from telecoms operators.

As John traces through the decades during which the telegraph and telephone were established in America, he draws heavily on primary sources to trace the ebb and flow of public and elite sentiment towards public ownership, regulation, and trustbusting. In John's hands, we see some of the most spectacular failures as more than a mismatch of regulatory strategy to corporate gambit – but rather as a mismatch of political will and corporate gambit. If a company's power would be best reined in by public ownership, but the political vogue is for regulation, then lawmakers end up trying to make rules for a company they should simply be buying giving to the post office to buy.

This makes John's history into a history of the Gilded Age and trustbusters. Notorious vulture capitalists like Jay Gould shocked the American conscience by declaring that businesses had no allegiance to the public good, and were put on this Earth to make as much money as possible no matter what the consequences. Gould repeated "raided" Western Union, acquiring shares and forcing the company to buy him out at a premium to end his harassment of the board and the company's managers.

By the time the feds were ready to buy out Western Union, Gould was a massive shareholder, meaning that any buyout of the telegraph would make Gould infinitely wealthier, at public expense, in a move that would have been electoral poison for the lawmakers who presided over it. In this highly contingent way, Western Union lived on as a private company.

Americans – including prominent businesspeople who would be considered "conservatives" by today's standards, were deeply divided on the question of monopoly. The big, successful networks of national telegraph lines and urban telephone lines were marvels, and it was easy to see how they benefited from coordinated management. Monopolists and their apologists weaponized this public excitement about telecoms to defend their monopolies, insisting that their achievement owed its existence to the absence of "wasteful competition."

The economics of monopoly were still nascent. Ideas like "network effects" (where the value of a service increases as it adds users) were still controversial, and the bottlenecks posed by telephone switching and human operators meant that the cost of adding new subscribers sometimes went up as the networks grew, in a weird diseconomy of scale.

Patent rights were controversial, especially patents related to natural phenomena like magnetism and electricity, which were viewed as "natural forces" and not "inventions." Business leaders and rabble-rousers alike decried patents as a federal grant of privilege, leading to monopoly and its ills.

Telecoms monopolists – telephone and telegraph alike – had different ways to address this sentiment at different times (for example, the Bell System's much-vaunted commitment to "universal service" was part of a campaign to normalize the idea of federally protected, privately owned monopolies).

Most striking about this book were the parallels to contemporary fights over Big Tech trustbusting, in our new Gilded Age. Many of the apologies offered for Western Union or AT&T's monopoly could have been uttered by the Renfields who carry water for Facebook, Apple and Google. John's book is a powerful and engrossing reminder that variations on these fights have occurred in the not-so-distant past, and that there's much we can learn from them.

Wu isn't wrong to say that John is engaging with a lot of minutae, and that this makes Network Nation a far less breezy read than Master Switch. I get the impression that John is writing first for other historians, and writers of popular history like Wu, in a bid to create the definitive record of all the complexity that is elided when we create tidy narratives of telecoms monopolies, and tech monopolies in general. Bringing Network Nation on my vacation as a beach-read wasn't the best choice – it demands a lot of serious attention. But it amply rewards that attention, too, and makes an indelible mark on the reader.

Support me this summer on the Clarion Write-A-Thon and help raise money for the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/07/18/the-bell-system/#were-the-phone-company-we-dont-have-to-care

#pluralistic#books#reviews#history#the bell system#monopoly#att#western union#gift guide#tim wu#richard r john#the master switch#antitrust#trustbusting

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WORLD'S FIRST ELECTRIC ROLLER COASTER

Granville T. Woods (April 23, 1856 – January 30, 1910) introduced the “Figure Eight,” the world's first electric roller coaster, in 1892 at Coney Island Amusement Park in New York. Woods patented the invention in 1893, and in 1901, he sold it to General Electric.

Woods was an American inventor who held more than 50 patents in the United States. He was the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Self-taught, he concentrated most of his work on trains and streetcars.

In 1884, Woods received his first patent, for a steam boiler furnace, and in 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called "telegraphony", would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, he patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. Woods caught smallpox prior to patenting the technology, and Lucius Phelps patented it in 1884. In 1887, Woods used notes, sketches, and a working model of the invention to secure the patent. The invention was so successful that Woods began the Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, to market and sell his patents. However, the company quickly became devoted to invention creation until it was dissolved in 1893.

Woods often had difficulties in enjoying his success as other inventors made claims to his devices. Thomas Edison later filed a claim to the ownership of this patent, stating that he had first created a similar telegraph and that he was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself, proving that there were no other devices upon which he could have depended or relied upon to make his device. After Thomas Edison's second defeat, he decided to offer Granville Woods a position with the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

In 1888, Woods manufactured a system of overhead electric conducting lines for railroads modeled after the system pioneered by Charles van Depoele, a famed inventor who had by then installed his electric railway system in thirteen United States cities.

Following the Great Blizzard of 1888, New York City Mayor Hugh J. Grant declared that all wires, many of which powered the above-ground rail system, had to be removed and buried, emphasizing the need for an underground system. Woods's patent built upon previous third rail systems, which were used for light rails, and increased the power for use on underground trains. His system relied on wire brushes to make connections with metallic terminal heads without exposing wires by installing electrical contactor rails. Once the train car had passed over, the wires were no longer live, reducing the risk of injury. It was successfully tested in February 1892 in Coney Island on the Figure Eight Roller Coaster.

In 1896, Woods created a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters, known as the "safety dimmer", which was economical, safe, and efficient, saving 40% of electricity use.

Woods is also sometimes credited with the invention of the air brake for trains in 1904; however, George Westinghouse patented the air brake almost 40 years prior, making Woods's contribution an improvement to the invention.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Harlem Hospital in New York City on January 30, 1910, having sold a number of his devices to such companies as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Until 1975, his resting place was an unmarked grave, but historian M.A. Harris helped raise funds, persuading several of the corporations that used Woods's inventions to donate money to purchase a headstone. It was erected at St. Michael's Cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens.

LEGACY

▪Baltimore City Community College established the Granville T. Woods scholarship in memory of the inventor.

▪In 2004, the New York City Transit Authority organized an exhibition on Woods that utilized bus and train depots and an issue of four million MetroCards commemorating the inventor's achievements in pioneering the third rail.

▪In 2006, Woods was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

▪In April 2008, the corner of Stillwell and Mermaid Avenues in Coney Island was named Granville T. Woods Way.

#granville t woods#black inventor#invented#world's first#electric roller coaster#1893#read about him#read about his invention#reading is fundamental#knowledge is power#black history

123 notes

·

View notes

Note

My ass fell down the Sherlock Holmes tree A G A I N and I am currently hitting every branch on the way down so literally anything you know about sending telegrams is useful information to me. Do they need stamps. How long do they take. Do I have to say Stop after every sentence or is that just a comprehension convention. IS IT A MORSE CODE THING

I AM REVVING MY ENGINES ABOUT THIS ASK AHHH LET'S GO

Telegrams did not need stamps. They were usually sent from one telegram office to another and were distributed outward by dedicated telegram couriers from that company. Most of the time, this system was faster than the mail.

Which is to say--THEY ARE SPEED. At telegraphy's height in the early 20th century, you could easily send a message across an entire country in a day. Telegram messages would get relayed up and down lines from office to office, sometimes passing through places like railroad stations, before arriving at the office closest to the recipient. Transatlantic messages shot across undersea cables in record time! It was bonkers! It's probably Samuel Morse's first message in his code (he didn't invent the telegraph, but the code's important) was: "WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT"

So the STOP thing is funky. There's a myth that people used it because telegraph companies provided the word for free in place of paying for punctuation, but that's probably not true. What is true is that the STOP really started showing up in telegrams during World War I. In this case, the STOP separated sentences clearly so messages wouldn't get misinterpreted and potentially cause things like horrible war disasters if someone read something incorrectly. Supposedly, the public caught onto using STOP and continued using it long after it was no longer necessary. It became a style of convention! It was en vogue!

(An aside is that one of the alternatives to STOP was using the numeral 30 in place of a period. This practice, as far as I'm aware, comes from newspapers using 30 to signal to the typesetter that they were at the end of a column. You can still find clippings of old newspapers that use this method! And sometimes you find telegrams using the same system!)

You, as the sender, would also pay by letter. This is why telegrams sound to us like these choppy, informal messages that are very easy to make fun of. If I remember correctly, the average length of an American telegram was about 11-12 letters. Very few people had the means to send long, flowery telegrams to each other or observe strict grammar rules. It was a whole lot easier to send the word NO than to say "I cannot come to your party, Geraldine, for I have a strong disdain for you as a person". It's also fun to look at some telegrams to see an early form of our text messaging acronyms. Some of them are so short that they're nonsensical to us.

So why send a telegram that says NO, anyway? Why not send a letter or, better yet, call the person? Because at the peak of telegraphy, both of those latter things are expensive and not always reliable. A rural farmer might not have the funds to make a long distance call, or straight-up doesn't have a telephone line! And what if their letter gets lost in the mail? What if the message is urgent? This is partially why a critical announcement of something like thee Armistice herself is delivered via telegram rather than someone calling and saying, "Yippee! The war's over!" Say it in tiny words and say it faster!

To date (and what I love to say to the kids I teach at the museum), sending a telegram is faster than sending a text message. If I sent the word NO through a telegraph line, it's already at its next stop the second I send it. If you texted the same word, you'd have to open the message prompt, type out the letters, send it, encode it, bounce it from a tower to a satellite and back down to another tower, have it go to the recipient's phone, decode it, and wait for them to open the prompt to read it. My NO is already there. :) (Now, I grant, it's going to take longer to get it on paper and sent through a courier to someone else, but if I work at a place like a railroad station and I'm sending a message to another station, then it's faster!)

Depending on the year you're looking for, there are a few different ways to send the telegram itself. There are telegraphic typewriters! Punch cards! Punch ribbons! Some guy wearing headphones and using a pencil! Someone else standing on a post and wildly waving flags around! A thing called a wigwag! Endless options!

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

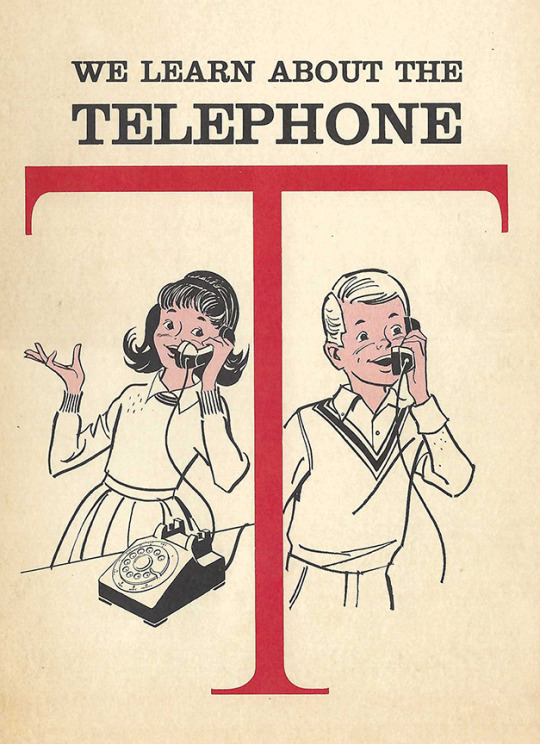

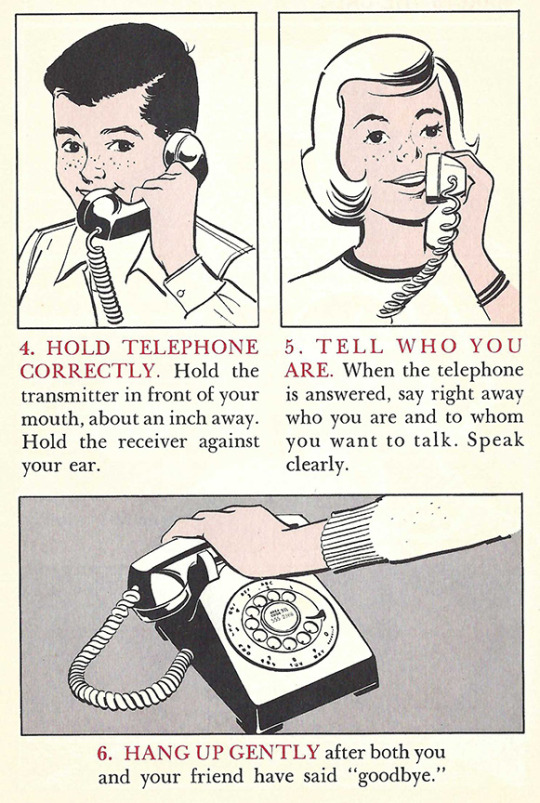

By 1947, over 60% of American households had landlines and telephones for personal use, which prompted the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) to produce an educational program for school aged children.

“Adventures in Telezonia” was introduced in 1950 as an 18 minute film that explained proper use of the telephone, with an accompanying teacher’s guide. The program was updated in 1964 and retitled, “We Learn About The Telephone - A Story About Communication”. (shown above)

The program included a 25 minute film and a 24 page booklet for students, and a teacher’s guide. For schools that didn’t have a film projector, the program offered a film strip, and certain schools had access to a teletrainer device where students could practice dialing a number and phone manners as outlined in the booklet.

Students learned about communication prior to the development of the telephone, how the telephone was invented, how sound waves work, and how the telephone works. More practically, the booklet illustrates how to use a telephone directory to find a number, and how to dial for help in an emergency- prior to the 911 system, children were directed to dial “O” and speak to the operator.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Granville T. Woods

Biography

(1856–1910)

Known as "African Edison," Granville Woods was an African American inventor who made key contributions to the development of the telephone, streetcar and more.

Who Was Granville T. Woods?

Granville T. Woods, born to free African Americans, held various engineering and industrial jobs before establishing a company to develop electrical apparatus. Known as "African Edison," he registered nearly 60 patents in his lifetime, including a telephone transmitter, a trolley wheel and the multiplex telegraph (over which he defeated a lawsuit by Thomas Edison).

Early Life

Born in Columbus, Ohio, on April 23, 1856, Woods received little schooling as a young man and, in his early teens, took up a variety of jobs, including as a railroad engineer in a railroad machine shop, as an engineer on a British ship, in a steel mill, and as a railroad worker. From 1876 to 1878, Woods lived in New York City, taking courses in engineering and electricity — a subject that he realized, early on, held the key to the future.

Back in Ohio in the summer of 1878, Woods was employed for eight months by the Springfield, Jackson and Pomeroy Railroad Company to work at the pumping stations and the shifting of cars in the city of Washington Court House, Ohio. He was then employed by the Dayton and Southeastern Railway Company as an engineer for 13 months.

During this period, while traveling between Washington Court House and Dayton, Woods began to form ideas for what would later be credited as his most important invention: the "inductor telegraph." He worked in the area until the spring of 1880 and then moved to Cincinnati.

Early Inventing Career

Living in Cincinnati, Woods eventually set up his own company to develop, manufacture and sell electrical apparatus, and in 1889, he filed his first patent for an improved steam boiler furnace. His later patents were mainly for electrical devices, including his second invention, an improved telephone transmitter.

#granvile t woods#african#kemetic dreams#edison#cincinnati#telephone#railroad#railway#railroads#african american

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

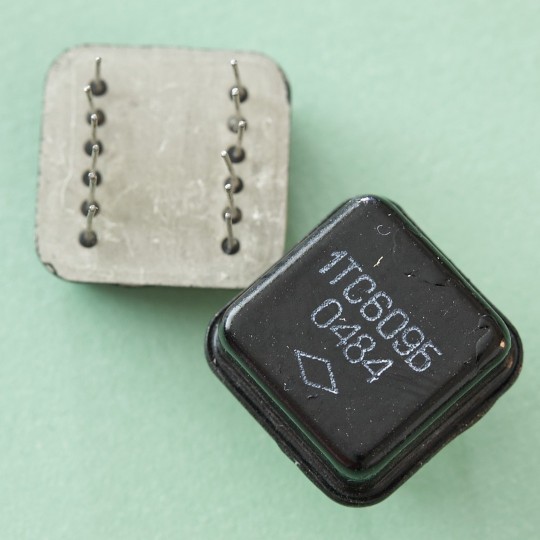

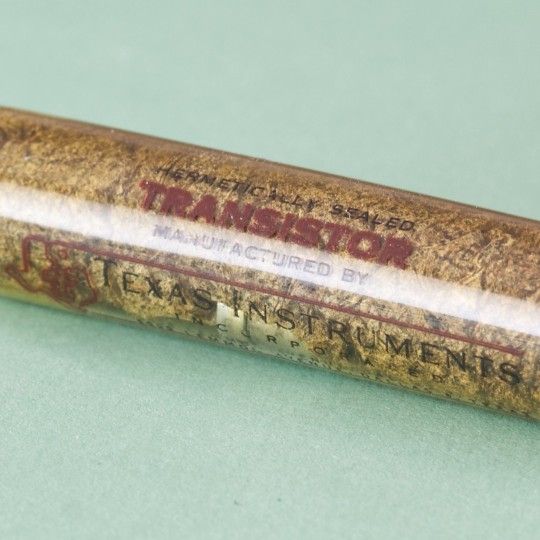

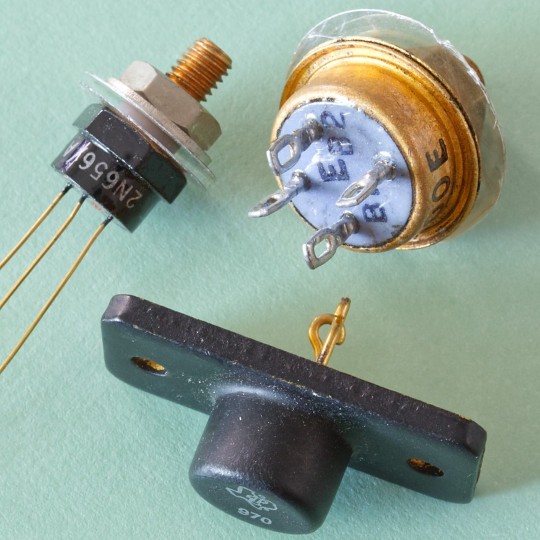

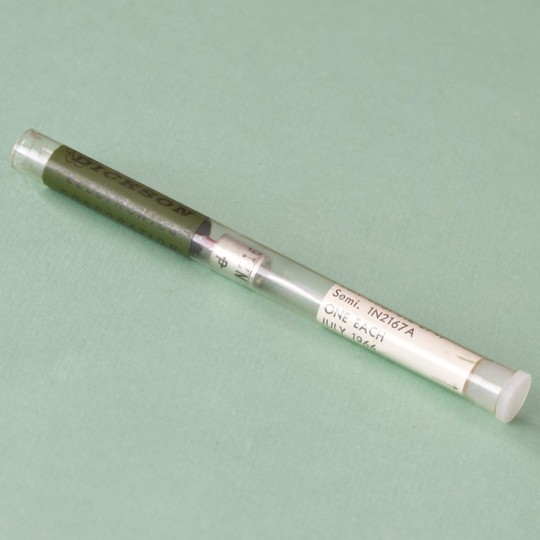

TRANSISTORS!

"... some unusual old-school transistor types and packages. Slide 1 is a Soviet 1ТC609Б, which is a package containing 4x PNP germanium transistors. Slides 2-4 are a (once-upon-a-time) hermetically sealed Texas Instruments 3N27 distributed by The American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T). Slide 5 shows a TO-3 Delco 2N456A made for the US Army, two 2N539As in different solder lug stud-mount packages marked JAN and Honeywell USN, a TI 2N1050 in a stud-mount package with leads, and an unbranded 2N340. Slide 6 shows a CBS 2N158 (the large black cyllindrical type) which is threaded on the top for screw-mounting, two TI types marked 0605 F032, a 2N498 with fins, and a Sprague MA-105B. Slide 7 shows a TI 2N122, an unbranded 2N656/A which is a stud-mount type with leads, and a large stud-mount type marked H200E with solder lugs. Last, slide 8 shows a sealed 1N2167A zener diode from Dickson Electronics dated July 1966. Dickson Electronics was based out of Scottsdale, AZ (very close to us!) and manufactured military-qualified zener diodes among other things.""some unusual old-school transistor types and packages. Slide 1 is a Soviet 1ТC609Б, which is a package containing 4x PNP germanium transistors. Slides 2-4 are a (once-upon-a-time) hermetically sealed Texas Instruments 3N27 distributed by The American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T). Slide 5 shows a TO-3 Delco 2N456A made for the US Army, two 2N539As in different solder lug stud-mount packages marked JAN and Honeywell USN, a TI 2N1050 in a stud-mount package with leads, and an unbranded 2N340. Slide 6 shows a CBS 2N158 (the large black cyllindrical type) which is threaded on the top for screw-mounting, two TI types marked 0605 F032, a 2N498 with fins, and a Sprague MA-105B. Slide 7 shows a TI 2N122, an unbranded 2N656/A which is a stud-mount type with leads, and a large stud-mount type marked H200E with solder lugs. Last, slide 8 shows a sealed 1N2167A zener diode from Dickson Electronics dated July 1966. Dickson Electronics was based out of Scottsdale, AZ (very close to us!) and manufactured military-qualified zener diodes among other things."

cred: instagram.com/amplifiedparts

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Lineman” by Norman Rockwell (1948)

American Telephone and Telegraph Company, (AT&T) advertisement, 1948.

Although Rockwell's illustration would promote the image of AT&T, its effect was meant to be inspirational rather than commercial. In a letter to Rockwell from the ad agency, it was suggested to Rockwell that he portray the lineman on a telephone pole in the act of restoring service after a storm. "The work of the linemen for the Telephone Company," said the account representative, "is filled with opportunities for personal sacrifices and acts which stem only from devotion to national welfare, so that it seems a fitting work to honor by such a painting."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

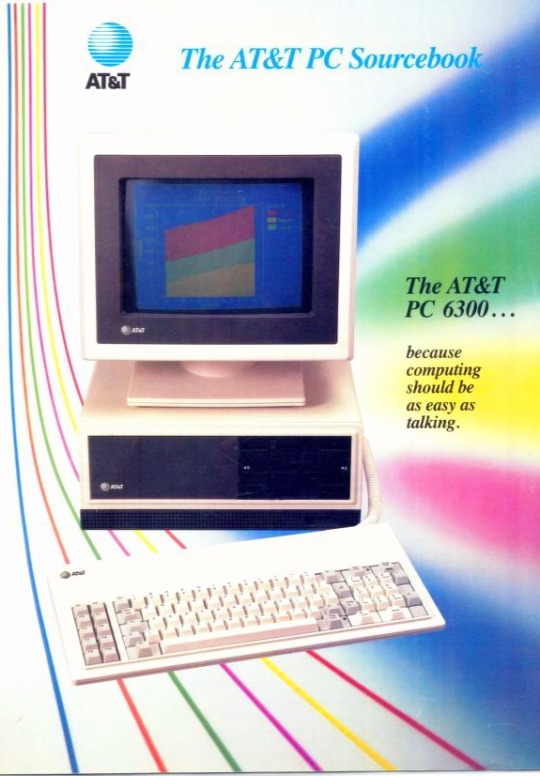

🇺🇲 Delve into the fascinating history of AT&T Information Systems, a subsidiary of American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T Corporation) that played an important role in the computer technology landscape. Established as one of the core units of AT&T following the breakup of the Bell System, AT&T Information Systems focused on computer technology ventures, telephone sales, and other unregulated business endeavors.

📊 As a strategic move to compete with industry giant IBM, AT&T Information Systems collaborated with Olivetti, leveraging their production capabilities to manufacture the AT&T PC 6300 series of computers. This series, alongside the 3B series computers and the AT&T UNIX PC, represented a multi-faceted approach to challenging IBM's dominance in the computer market.

💻 The AT&T PC 6300 series showcased AT&T Information Systems' commitment to innovation and technological advancement. By harnessing the power of collaboration and strategic partnerships, AT&T Information Systems sought to carve out a niche in the competitive computer industry landscape.

#TechTime Chronicles#electronic#electronics#tech#technology#old technology#at&t#ibm#ibm pc#unix#unix pc#computer#computers#computing#companies#corporations#business#industry#information technology#information systems#1980s computers#1980s#1980s commercials#telecomindustry#telecominnovation#operation system#made in usa#telecomunications#innovation#usa

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

For more than a century and a half, an organization that has been referred to as “the most important agency you’ve never heard of” has been making technology global.

In its latest iteration, as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), its global regulations now underpin most technologies we use in our daily lives, setting technical standards that enable televisions, satellites, cellphones, and internet connections to operate seamlessly from Japan to Brazil.

The next big technology may present the organization with its greatest challenge yet. Artificial intelligence systems are being deployed at a dizzying pace around the world, with implications for virtually every industry from education and health care to law enforcement and defense. Governments around the world are scrambling to balance benefits and bogeys, attempting to set guardrails without missing the boat on technological transformation. The ITU, with 193 member states as well as hundreds of companies and organizations, is trying to get a handle on that rowdy conversation.

“Despite the fact that we’re 158 years old, I think that the mission and mandate of the ITU has never been as important as it is today,” said Doreen Bogdan-Martin, the agency’s secretary-general, in a recent interview.

Founded in 1865 in Paris as the International Telegraph Union and tasked with creating a universal standard for telegraph messages to be transmitted between countries without having to be hard-coded into each country’s system at the border, the ITU would subsequently go on to play a similar role in future technologies including telephones and radio. In 1932, the agency adopted its current name to reflect its ever-expanding remit — folding in the radio governance framework that established maritime distress signals such as S.O.S. — and was brought under the aegis of the United Nations in 1947.

Bogdan-Martin, who took office in January, is the first woman to lead the ITU, and only the second American. Getting there followed months of campaigning to defeat her opponent, a former Russian telecommunications official who also worked as an executive at the Chinese technology firm Huawei, in an election that was widely billed as a battle for the future of the internet, not to mention a key bulwark for the West in the face of an increasingly assertive China and Russia within the U.N. (Bogdan-Martin also took over the ITU leadership from China’s Zhao Houlin, who had served for eight years after running unopposed twice.)

“It was intense,” Bogdan-Martin acknowledged. Ultimately, she won with 139 out of 172 votes cast.

Russia and China have been at the forefront of a competing vision for the internet, in which countries have greater control over what their citizens can see online. Both countries already exercise that control at home, and Russia has used the war in Ukraine to further restrict internet access and create a digital iron curtain that inches closer to China’s far more advanced censorship apparatus, the Great Firewall. In a joint statement last February, the two countries said they “believe that any attempts to limit their sovereign right to regulate national segments of the internet and ensure their security are unacceptable,” calling on “greater participation” from the ITU to address global internet governance issues.

“I firmly support a free and open, democratic internet,” Bogdan-Martin said. Those values are key to her biggest priority for the ITU—bringing the internet to the 2.7 billion people worldwide who still haven’t experienced it. “Safe, affordable, trusted, responsible, meaningful connectivity is a global imperative,” she said.

Getting that level of global consensus on how to regulate artificial intelligence may not be as straightforward. Governments around the world have taken a variety of approaches—and not always compatible. The European Union’s AI Act, set for final passage later this year, ranks AI applications by levels of risk and potential harm, while China’s regulations target specific AI applications and require developers to submit information about their algorithms to the government. The United States is further behind the curve when it comes to binding legislation but has so far focused on light-touch regulation and more voluntary frameworks aimed at allowing innovation to flourish.

In recent weeks, however, calls for a global AI regulator have grown louder, modeled after the nuclear nonproliferation framework governed by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Proponents of that idea include U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, whose advanced chatbots have catalyzed much of the hand-wringing around the technology. But some experts argue that comparisons to nuclear weapons don’t quite capture the challenges of artificial intelligence.

“People forget what a harmony there was between the [five permanent members of the Security Council] in the United Nations over the IAEA,” said Robert Trager, international governance lead at the nonprofit Center for the Governance of AI. When it comes to AI regulation these days, those members “don’t have the same degree of harmony of interest, and so that is a challenge.”

Another difference is the far wider application of AI technologies and the potential to transform nearly every aspect of the global economy for better and for worse. “It’s going to change the nature of our interactions on every front. We can’t really approach it and say: ‘Oh, there’s this thing, AI, we’ve now got to figure out how to regulate it, just like we had to regulate automobiles or oil production or whatever,’” said Gillian Hadfield, a professor of law at the University of Toronto who researches AI regulation. “It’s really going to change the way everything works.”

The sheer pace of AI development doesn’t make things any easier for would-be regulators. It took less than six months after the launch of ChatGPT caused a seismic shift in the global AI landscape for its maker, OpenAI, to launch GPT-4, a new version of the software engine powering the chatbot that can incorporate images as well as text. “One of the things we’re seeing with the EU AI Act, for example, is it hasn’t even been passed yet and it’s already struggling to keep up with the state of the technology,” Hadfield said.

But Bogdan-Martin is looking to get the ball rolling. The ITU hosted its sixth annual AI for Good Global Summit last week, which brought together policymakers, experts, industry executives, and robots for a two-day discussion of ways in which AI could help and harm humanity—with a focus on guardrails that mitigate the latter. Proposed solutions from the summit included a global registry for AI applications and a global AI observatory.

“Things are just moving so fast,” Bogdan-Martin said. “Every day, every week we hear new things,” she said. “But we can’t be complacent. We have to be proactive, and we do have to find ways to tackle the challenges.”

And although total consensus may be hard to achieve, there are some fundamental risks of AI that experts say countries will be keen to mitigate regardless of their ideology—such as protection of children—that can form something of a baseline.

“No jurisdictions, no states, have an interest in civilian entities doing things that are dangerous to society,” Trager said. “There is this common interest in developing the regime, in figuring out what the best standards are, and so I think there’s a lot of opportunity for collaboration.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A telephone, without a connection at the other end of the line, is not even a toy or a scientific instrument. It is one of the most useless things in the world. Its value depends on the connection with the other telephone — and increases with the number of connections.

—Theodore Vail, American Telephone and Telegraph Company, 1905

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

5 Notable Black Inventors

1. Madam CJ. Walker Born in 1867 and died in 1919. After suffering hair loss of her own from a scalp disorder she began working on the development of hair care products for African Americans.

2. Elijah McCoy Born in 1843 and died in 1929. This noted African American inventor was issued more than 57 patents for his inventions during his lifetime. His best known invention was a cup that fed lubricating oil to machine bearings through a small bore tube. Machinists and engineers who wanted genuine McCoy lubricators used the expression “the real McCoy.”

3. Garrett A. Morgan Born in 1887 and died in 1963. He developed both the first traffic signal invention and the first patented gas mask.

4. Granville T. Woods Born in 1856 and died in 1910. Granville is known to many as “The Black Edison,” because both were great inventors who came from disadvantaged childhoods. But unlike Edison, Woods was considered fortunate to receive an education to help him on the road to his inventions. He invented the telegraphony. The telegraphony combined features of both the telephone and telegraph and was purchased by Alexander Graham Bell’s company. He later fought with Thomas Edison over patents for the telegraph.

5. Jan Ernst Matzeliger Born in 1852 died in 1889. Jan invented a shoemaking machine that increased shoemaking speed by 900%! This allowed for lower prices for consumers and more jobs for workers. Matzeliger left behind a legacy of tackling what was thought to be an impossible task – making shoes affordable for the masses.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For twenty minutes you’ve been receiving the same exact signal?

You mean, given the time period, Morse code?

Because the first transatlantic phone convo won’t happen until the 20s.

Also:

30 December 1899: American Bell Telephone Company is purchased by its own long-distance subsidiary, American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) to bypass state regulations limiting capitalization. AT&T assumes leadership role of the Bell System.

And we still have to tolerate AT&T today.

#ashleybenlove posts#1899#1899 spoilers#season 1#The Ship#my house's landline (yeah I know) is with AT&T.

2 notes

·

View notes