#although setting it up was pretty strange because it’s default wasn’t English but it was reading English words

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I’ve been low key struggling with my art history class because a lot of it is reading a textbook online, which is hard for someone who spends most of their free time getting instant gratification from the internet and thus has a low attention span (also someone who may or may not have undiagnosed dyslexia-)

And then I remembered that there are tools for people who struggle with this kind of stuff, and that I don’t have to just struggle through each chapter like an idiot! Text to speech is so handy, even if it’s just to help me not get distracted while I read at the same time, and to help me not lose my place when reading.

#I do need to work on the whole low attention span thing..#but this is nice!#although setting it up was pretty strange because it’s default wasn’t English but it was reading English words#so some pretty scary sounds were produced..#and I also realized all the ‘American’ English ones are terrifying#so I’m using the Australian English ‘Karen’ apparently#college

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ghosted Films: A Director’s Nightmare.

To mark a conversation with Peter Medak about his new documentary The Ghost of Peter Sellers, which details a particularly tumultuous early 1970s film shoot, Dominic Corry looks at how the inherently nightmarish pursuit that is filmmaking has informed other movies.

“Every frame you set up references yourself and your entire life, so bits and pieces indirectly of your life go into every movie.” —Peter Medak

On a certain level, filmmaking is an essentially traumatic experience. The extreme number of moving parts, umpteen tiers of variables—both creative and practical—and the cacophony of egos involved all amount to what in the best-case scenario could generously be considered organized chaos.

And for the most part, it all falls on the director’s shoulders. Although the long-prevailing auteur theory is regularly and healthily challenged these days, our default perception tends to be that whatever happens, good or bad, it’s the director’s fault. Some directors process their filmmaking nightmares by writing a review of the film on Letterboxd. But in the case of journeyman filmmaker Peter Medak (The Changeling, The Krays, Romeo Is Bleeding), he chose to process his filmmaking trauma by… making a film about it.

The Ghost of Peter Sellers revisits the making of the 1974 Peter Sellers-starring pirate comedy Ghost in the Noonday Sun, an infamous folly of a film that has long haunted Medak. It’s also one of those rare films on Letterboxd: at the time of writing it has just two reviews, and only 26 members in a community of two million have noted seeing it. Giving it one and a half stars, EWMasters writes: “Pretty awful. I mean talk about throwing it on the stoop and seeing if the cat’ll lick it up. There is one very good sequence where the crew goes to town on this big plate of fish and vegetables that’s really well done—but otherwise, this is really only worth the time of a Sellers completist��. (Perhaps the main character’s name—Dick Scratcher—should have sounded alarm bells.)

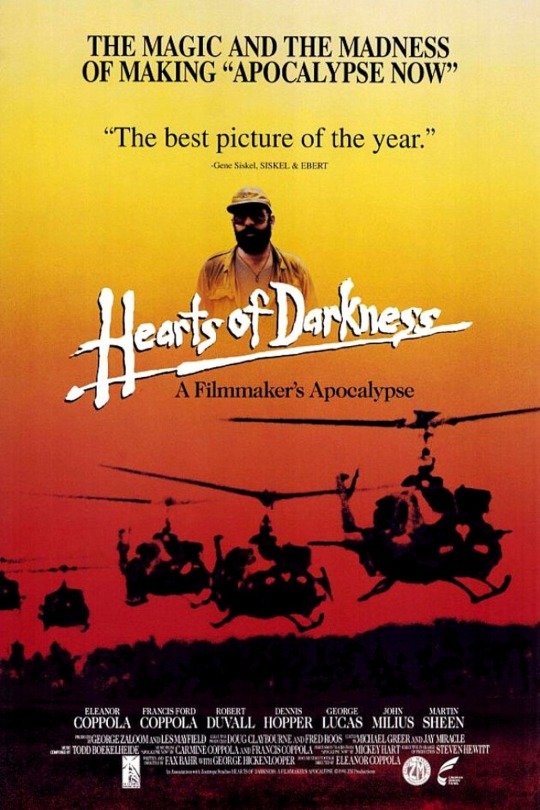

Medak is not the first filmmaker to spin non-fictional gold out of a director’s nightmare (in this case, his own). His movie follows in the footsteps of legendary documentaries such as Fax Bahr and George Hickenlooper’s 1991 film Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, which revealed the full extent of the already infamous insanity that comprised the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 classic Apocalypse Now, and used extensive footage shot at the time by Coppola’s filmmaker wife Eleanor (filmmaker spouses are handy to have along for the ride, as Nicolas Winding Refn also knows). And there’s Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s 2002 work Lost in La Mancha, which detailed Terry Gilliam’s (ironically?) Sisyphean efforts to film an adaptation of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote.

In both instances, the films in question were (eventually) made—and released to some acclaim (one considerably more than the other)—but as The Ghost of Peter Sellers shows, the shooting of Ghost in the Noonday Sun was such an epic boondoggle that the unfinished film sat unreleased for years and was much later released to no acclaim whatsoever.

The uphill battle to make his never-released horror movie Northwestern made indie filmmaker Mark Borshadt an unlikely filmmaking hero thanks to the breakout success of Chris Smith’s 1999 documentary American Movie. Like with Ghost in the Noonday Sun, the efforts to make a film proved more interesting than the film being made.

Jennifer Jason Leigh and Kevin Bacon in ‘The Big Picture’ (1989).

There are several narrative films of note that have successfully captured the specific pandemonium of filmmaking. Richard Rush’s 1980 cult classic The Stunt Man follows a fugitive who stumbles his way into the titular job on a big chaotic Hollywood production (Peter O’Toole plays the Machiavellian director), while Christopher Guest’s under-appreciated 1989 comedy The Big Picture stars Kevin Bacon as a hot young director who is roughed up by the Hollywood machine. It’s a notable and often overlooked antecedent to The Player, and like the Robert Altman classic, is more about ‘the business’ overall than the specifics of filmmaking, although in both cases Hollywood proves itself analogically appropriate.

Playwright, writer and director David Mamet’s own filmmaking experiences obviously inform his 2000 comedy State and Main, in which a Hollywood production takes over and smothers a small town with its singular thinking. It’s not hard to imagine Mamet processing his own filmmaking trauma in State and Main, just as the Coen brothers famously did in Barton Fink, their ode to writer’s block supposedly inspired by the difficulty they had penning the screenplay for Miller’s Crossing.

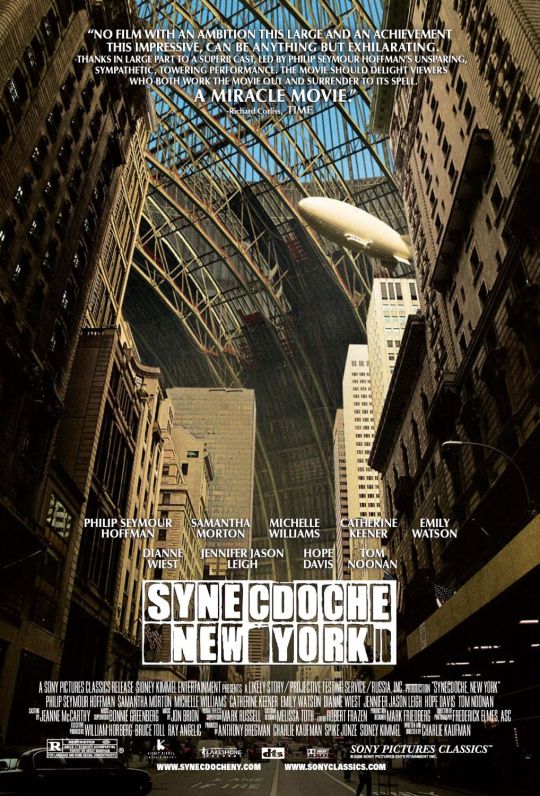

Charlie Kaufman channeled his own creative struggles into the screenplay for the 2002 masterpiece Adaptation, then built on those themes with his wildly ambitious 2008 directorial debut Synecdoche, New York, whose more maddening aspects arguably capture the irrational nightmare that is filmmaking better than any film directly ‘about’ filmmaking.

With her 2018 documentary Shirkers, writer Sandi Tan gained some measure of closure regarding an indie film she had starred in and written in her home country of Singapore, in 1992. The documentary (which shares its name with the original movie) has her revisiting the footage from the never-released film, which was stolen (!) 25 years previously by its director—and Tan’s filmmaking mentor—George Cardona.

Back to Peter Medak. In The Ghost of Peter Sellers, which premiered at Telluride Film Festival in 2018 and has just had its virtual screening release, we learn that Hungarian-born Medak was a rising directing star in the early 1970s in London, hot off the Oscar-nominated Peter O’Toole film The Ruling Class. Unable to resist an offer to work with Peter Sellers, then comedy’s reigning superstar—mostly thanks to Blake Edwards’ Pink Panther films—Medak set about shooting a treasure-hunting pirate film on the island nation of Cyprus in the Mediterranean.

In addition to the usual production problems associated with shooting on boats, Medak had to contend with the titanically and infamously fickle Sellers, who quickly turned on him and attempted to get him fired. Sellers also antagonized the other actors, then, after failing to get the production shut down, brought in his friend and longtime creative collaborator Spike Milligan to try and salvage the film, but things kept going wrong, leaving Ghost in the Noonday Sun unfinished and Medak with the blame for the production’s troubles.

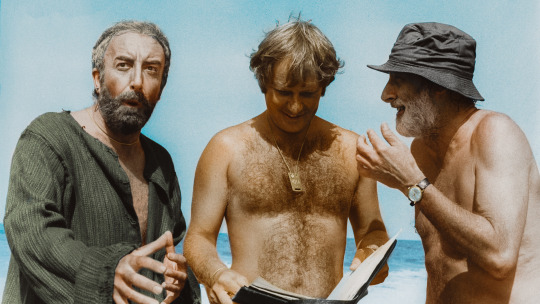

Director Peter Medak with Peter Sellers (as Dick Scratcher) and Spike Milligan (as Bill Bombay) on the set of ‘Ghost in the Noonday Sun’, finally released in 1984.

Although Medak’s career recovered, he has clearly been carrying around a lot of hurt associated with the experience, and it’s remarkable watching him work through that on screen by revisiting Cyprus, telling the story of the shoot, and talking to some of the people involved. Sellers (who died in 1980) looms large over the film, but it also has interesting content surrounding the great Spike Milligan, who died in 2002.

Why did you decide to revisit this experience with a documentary? Peter Medak: Because it’s been haunting me for all these years. Because it should’ve been a really very successful film and I was blamed for everything going wrong, when in fact it had nothing to do with me. It was due to Peter’s changing mind and state of mind, and all kinds of things had physically gone wrong on the film. It was always easiest to blame the director for everything and my career at the time was very high up after [The] Ruling Class and this should’ve been the icing on the cake and it wasn’t.

It really bothered me for many years afterwards, even though I went on working. I was asked to do it by the producer of the documentary and I originally said “It’s the last thing I want to do”, because it would mean I would have to go back to Cyprus where I shot the original movie and go on the water, and I never want anything to do with water anymore because a lot of the disasters on the film, production-wise, were all connected with shooting at sea, which is totally impossible to do. Then I thought: well, you know, I should just do it and try to explain what happened on the film. And because some of the explanations were funnier scenes than the original film. So that’s why I did it.

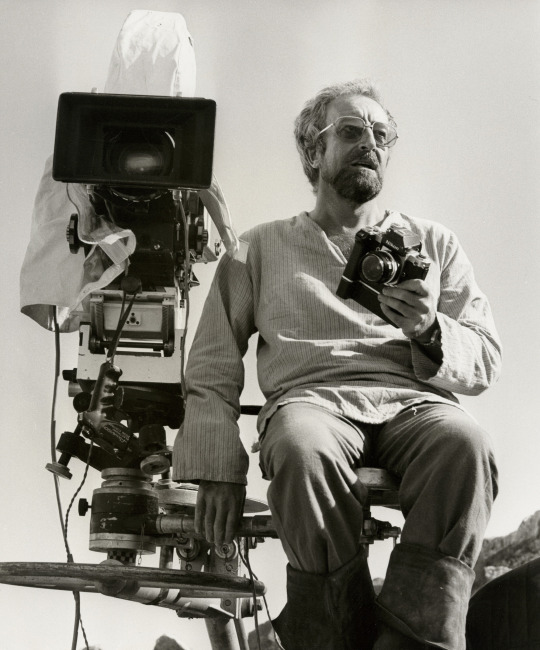

Peter Medak fishing for answers in ‘The Ghost of Peter Sellers’.

In the documentary, you talk about needing to free yourself from the experience by making this film. Do you feel like you achieved that? Well, I think I did because I had a wonderful time doing it. A very sad time at the same time because when you go back to places where you shot 45 years before, it creates a very strange kind of illusion inside your mind, your heart and everything of the time. And having been there then and then being there again, it’s a very strange kind of a supernatural feeling in a way. It felt like you have died and your ghost is actually revisiting all these things you know. I called it The Ghost of Peter Sellers because it sounds good and also because the original film was called Ghost in the Noonday Sun, and this ghostly feeling of mine of revisiting that island after all these years, it’s a very, very strange feeling and somehow the film captures that emotionally.

Do you feel like the large distance from the shoot was necessary to be able to revisit it? It’s not that I thought about it every day of my life, but I talked about it to all the people who I worked with in my following career. When I was doing Romeo Is Bleeding with Gary Oldman, my darling Gary said to me one day, “You know, we are crazy, what we should do is make a movie about your movie, but I don’t want to play Peter Sellers, I want to play you, with your Hungarian, broken-English accent.” We had a script written but we never did it. That was a good 25 years ago.

Peter Medak in front of a promotional poster for ‘Zorro, The Gay Blade’, his 1981 film starring George Hamilton and Lauren Hutton.

So you had considered doing a scripted version of it? Yeah, but I don’t know quite what we would’ve done. I said to Gary at the time: “I never want to go on a boat again”, and so I thought in my mind that the scenes would start each day [with] the characters getting off the pirate ship and they come ashore—that’s where the scenes would begin. I’m sure we would’ve done something quite wonderful, and it would’ve maybe explained the things the [documentary is] trying to explain because I guess that’s what has unconsciously driven me. Because [for the documentary], we didn’t write one word of it, I just completely did it out of instinct. Where I want to shoot, what I want to shoot, and how we should go from here to there. I loved it, so going back on to it was quite easy. It did show me actually what a wonderful medium it is, documentary, because you can do anything with it. It’s a much freer form than scripted movies. Which is rigid. And this is liquid.

Did you have any other documentaries about filmmaking in mind when you went into this? Not really. I knew Terry Gilliam’s Lost in La Mancha, because I love Terry and I love his films and we know each other and knew each other. Terry was very fortunate, because he had so much trouble before on Baron Munchausen, that he decided to have a documentary film crew filming the whole process, so he had the material available, which allowed him to make his film. I said to him after [a screening], “You were lucky because you didn’t make the movie. I had to suffer through 90-something days of shooting with Peter [Sellers].” But of course since then, Terry made the film, and he made something slightly different than what he was originally gonna do.

Peter Medak retraces his steps in ‘The Ghost of Peter Sellers’.

Did any of your subsequent films feel nearly as difficult? Most movies are very difficult to make, and always when you anticipate problems, they never seem to happen. When I did The Changeling, everybody said “George C. Scott is very, very difficult to work with” and he was an absolute angel with me and [it was] the easiest thing to do. It was a wonderful ghost story. I’m very proud of that film. It will live forever. All movies are like your kids, your own children, because you put so much emotion, so much of your soul. That’s what I’m saying to [Ghost in the Noonday Sun executive producer] John Heyman [in The Ghost of Peter Sellers]: the director’s viewpoint is completely different from the producer’s because every frame you set up references yourself and your entire life, so bits and pieces indirectly of your life go into every movie. Because of that it becomes an incredibly personal journey when you put your absolute soul on the line. When it gets criticized or not accepted or whatever, one takes it very personally because the whole thing came from a very personal experience, even though the subject may be nothing to do with you.

Peter Sellers on the set of ‘Ghost in the Noonday Sun’.

Even within the canon of famously difficult performers, Peter Sellers is notorious. How would you describe him to a modern audience? Well he was a genius, there’s no question about it. But he was a manic-depressive person. And it’s a generalization, but most of the great comics are manic-depressive. And he changes his mind all the time. One minute, he loves you, next minute, he hates you. One minute he loves the subject, next minute he doesn’t wanna do it, he wants to get out and all that. So it is very up and down. When you’re running film with a crew of 150 people, and boats on the sea, and weather’s changing and everything, you can’t have that, because you fall behind the schedule and things go wrong.

At one point very early on, all he wanted to do was get off the movie. And then he did everything he [could] to sabotage the film so the film would close down and he wouldn’t have to finish it. But it didn’t just happen on my film, it happened with all his biggest successes, including the Pink Panther movies. Because if you look into Blake Edwards, each one was an absolute nightmare for the director and for the film company, United Artists. And I was gonna include that in the documentary but it had nothing to do with the Ghost in the Noonday Sun so I didn’t. I actually shot some scenes with one of the executives from United Artists at that time who had to deal with the insanity of Peter and also Blake Edwards. I say ‘insanity’; I didn’t want to say it too much in the documentary because I love Peter, even today. And it’s wrong for me to accuse him of those things because it sounds like I’m excusing myself. Peter was crazy. There’s no other way one can describe it. Touched by God. And so was Spike Milligan. But Spike had the love of goodness. Peter had kind of a nasty streak on him when he turned on people.

There’s a moment in the documentary where you suggest that Spike Milligan is more influential than he gets credit for. Do you think he’s under-appreciated? Totally. Totally. Totally. Because his talent was absolutely, monumentally genius. I always say this, but Spike basically created Peter Sellers through [legendary BBC radio programme] The Goon Show. And he also gave him all those various characters and developed those voices for him. It’s all in The Goon Show. The Monty Pythons, they were inspired by The Goon Show and they made it into television. Not story wise, but style wise. That kind of zany, insane humor. Spike was a total genius. Not that Peter wasn’t, but they stood together, completely overwhelmingly wonderfully insane. But Spike was quite something. He was incredibly human, he was incredibly gentle. And incredibly kind. Peter was incredibly combative. And he had that most incredible ego.

But all our lives come from our backgrounds and what our past was and where we come from, and Peter had a very sad upbringing and a very sad life and he was tremendously influenced by his mother. When his mother passed away, he kept on talking to her for ten years. When he came to Cyprus to make the movie, he arrived with big blow-up [photos] of Liza Minnelli—who he’d just broken up with a week before—and his mum. And it sounds terrible when one says it, but psychologically, some of the answers are there. But at the same time, both Peter and Spike, I can’t tell you what a gift it was… I mean the reason I did the film is: who could give up the chance of actually working with Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan? It doesn’t matter what the fucking script is, you know? It was a wonderful thing and I would do it all over again tomorrow.

Related content

Our Showdown on films within films

‘The Ghost of Peter Sellers’ is screening in virtual theaters now. It will be available via video on demand services from June 23. A list of all the films mentioned in this article can be found here. Comments have been edited for clarity and length.

#peter medak#peter sellers#ghost in the noonday sun#the ghost of peter sellers#filmmaking fails#directing#documentary#filmmaking process#filmmaking#spike milligan#the goon show#monty python#the specific pandemonium of filmmaking#epic boondoggle#letterboxd

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Blue Java Bananya

Well here's something I wasn't planning on making at all! This year certainly started off with a bang!, and not a good one, what with my drawing tablet going kaput on me. But at the very least, thanks to my brother I have a temporary solution. He was able to get his hands on a Surface Pro 3 through work, and after acquiring a stylus I've been working on adapting to it for the time being. It's taking a lot of getting used to, but I'd rather have to get used to this than have nothing at all until next century when I can afford a more proper replacement. Anyway. That whole fiasco just depressed and stressed me out to no end, among other life things. For my birthday, I was gifted a DVD of Bananya, a show about, you guessed it--banana cats like the one I've drawn here. I watched the whole thing (about 40 minutes, the episodes are pretty short) in one sitting, and for that time I was able to forget about everything that was worrying me and just enjoy some cute fruit kitties and simple fun. No over-the-top, save-the-world plot, no complicated character dynamics, no overcoming past trauma, just fun and cute. I knew about Bananya for a while, as a couple of years ago I got my hands on a couple of plushies before I even knew the show existed; I just thought the concept of cat-bananas with velcro peels was adorable. It was only later when I was wondering where they originated from that I found out there was a show, and subsequently that the only way to watch the English dub was on the DVD. (No offense to anyone that prefers subs over dubs; I just have a really hard time splitting my attention between what's happening and who's saying what and trying to read the text. Plus I have a hard time sitting down and just watching a show and doing nothing else; dubbed makes it possible for me to do other things and not have to stare at the screen and hope I can read fast enough.) Since I had bananas on the brain after that and it's a really simple and cute art style, I decided to test out getting accustomed to the Surface Pro that I'd draw a little Bananya OC of sorts. In the show, the bananyas are named more so for the cat part of their appearance, usually, but I wanted mine to stand out a bit more and I'm pretty sure that if they aren't already that eventually, all the default cat-pattern names are going to be canonically taken. So I went and I looked up strange/different types of bananas and discovered the blue java or "ice cream" banana, which has a bluish tint to the peel when it's young, and because of it's vanilla taste and creamy texture, it's actually offered as a healthier alternative to ice cream in areas where it's more commonly found (hence the nickname). And now I really want to try one but I haven't the foggiest idea where I'd find them here in the states. My other option was a red/pink variety and the show already has at least 2 bananyas with pink peels and one with pink on her head, so I took the blue banana and ran with it. (Although upon further inspection, I think the newer bananya episodes they're currently working on that haven't been dubbed yet feature one with a blue banana peel so I may still not be completely unique here despite my efforts.) I went with more of a teal/greenish-blue as opposed to a more "true" blue, since even in pictures while the blue java is definitely blue compared to the average banana, it's not blue like a blue raspberry candy is blue. They're actually a pretty pastel kind of almost mint color-- And suddenly, as I'm typing this I think I better understand why vanilla Tootsie Rolls come in a blue wrapper...are they based on these bananas?? Does anybody know?? --*ahem* As I was saying... The bananas, from what I understand, also lose/fade that blue color as they mature. Which would explain why I couldn't seem to find a picture of a peeled Blue Java banana that had that same pastel-colored peel. But I went with it anyway. (This is a show about banana cats, I don't think we have to be 100% scientifically accurate here.) I also added some black spots to the cat part of my bananya, as I haven't seen a white-with-black-spots one in canon material and I have a bit of soft spot for black-and-white kitties in particular. And while I have had second thoughts that maybe her name should be "ice cream bananya" instead (for the reasons I went over earlier about the real bananas), I ultimately when with Blue Java Bannaya, as it very on-the-nose like the other bananya names, and in a way I think the "java" part fits with the black spots. But that's mostly just because java makes me think of "java chip frappucino" from Starbucks, which makes me think of chocolate chips, which are usually dark spots in cookies...see where I'm going with this? Though on the other hand, the black and white also kinda makes me think of Oreos, which would tie-in with the ice cream thing because usually Cookies n Cream ice cream is made with Oreos or knock-off Oreos, so I suppose it would've been equally fair to name her "Cookie Bananya" or something... Eh, for now, she stays as Blue Java. Or just "Java" for short. It was pretty straight forward to draw her, as I mentioned that the bananya style is pretty simple. Dare I say minimal? The main struggles I had boiled down to the learning curve with the Surface Pro and the new stylus. The pen pressure, maybe obviously, isn't as good as I'm used to, and the disparity between the tip of the pen and where the cursor actually is is different, and I think there's a little bit of lag when I'm drawing but that might be more to do with me having the stabilizer turned up a bit higher than normal in trying to compensate for the other issues. Still, I was at least able to manage for something as simple as this. I am admittedly horrified at the prospect of one of my usual, more complex digital drawings though...learning curves and baby steps... I'm not happy about the tablet situation, but at least the bananya is cute so I can focus on that instead. I do sincerely hope I'm very wrong about how long I'm going to be using this new set-up for though, because the way things are going it's going to be a very long time before I have the option of a better alternative... ____ Artwork/Character © me, MysticSparkleWings I do not own Bananya ____ Where to find me & my artwork: My Website | Commission Info + Prices | Ko-Fi | dA Print Shop | RedBubble | Twitter | Tumblr | Instagram

1 note

·

View note

Link

I CAME LATE TO Raymond Chandler, and I don’t know if it was in the best or worst possible way. I had my degree in literature, and I had read not a single word by Chandler. It was a rainy afternoon in London and I needed to kill a couple of hours, so I went to see a showing of The Big Sleep. The film I saw, however, wasn’t the 1946 Bogart-Bacall classic (which I’d only heard about), it was the 1978 remake directed by Michael Winner and set improbably, unconvincingly, in England. The film is universally despised. Roger Ebert said it “feels kind of embalmed,” although plot-wise it’s strangely faithful to the novel, and the cast is fantastic — Jimmy Stewart, Candy Clark, Richard Boone, Oliver Reed, with Robert Mitchum as Philip Marlowe. Mitchum has always seemed to me the perfect Marlowe, and far more believably tough and insolent than Humphrey Bogart; I just wish he’d played the part 20 years earlier. He first played Marlowe in 1975 in Farewell, My Lovely, when he was in his late 50s; he was 60 by the time he made The Big Sleep, and he doesn’t look a youthful 60.

You could argue that if Chandler’s genius could shine through that dreadful adaptation, then it’s pretty much unassailable. And shine through it did. I was hooked, and went back to the source. I immediately read The Big Sleep (1939), his first novel, and then the rest of the oeuvre, and I’ve been increasingly hooked ever since. I consider myself an enthusiast rather than an expert or a scholar, although there’s a shelf in my office heavy with Chandler-related volumes: the letters, the biographies, the notebooks, and various Los Angeles–related items that include Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles (1987), Chandlertown: The Los Angeles of Philip Marlowe (1983), and Tailing Philip Marlowe: Three Tours of Los Angeles — Based on the Work of Raymond Chandler (2003). The Annotated Big Sleep, with a short but excellent foreword by Jonathan Lethem, will eventually join them.

But here’s the question: when I read The Big Sleep for the first time (or subsequently, for that matter), was there much in there that I didn’t understand? And I’m not talking about plot matters such as who killed the chauffeur, or why the cute but borderline-insane murderess isn’t prosecuted, but rather matters of fact and vocabulary.

Did I feel the need to reach for the dictionary and look up “swell” when Marlowe says to Vivian Sternwood, “I don’t mind your showing me your legs. They’re very swell legs”? Did I wonder what a jerkin was, or a chiseller, or a bookplate? Was I puzzled by the terms “hot toddy” and “got the wind up”? Did the words parquetry, stucco, or croupier seem unfamiliar? After I’d read that General Sternwood was propped up in “a huge canopied bed like the one Henry the Eighth died in,” did I feel the urge to check the date of Henry VIII’s death?

Honestly, I did not — but Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto, the three editors of The Annotated Big Sleep, certainly think that all those things I’ve listed are worthy of explanation, which, I think, raises the question of who reads The Big Sleep and who those annotators think reads The Big Sleep.

Pico Iyer, in his essay “The Mystery of Influence” (2002), says of Marlowe, “Of all the great figures of the twentieth century, he seems one of the most durable, in part because he travels so well and so widely.” And he tells us that Haruki Murakami began his career by translating Chandler into kanji and katakana scripts. It’s not hard to imagine that Japanese readers might find something of the noble, tarnished samurai in Marlowe, though what they make of a line like, “She has to blow and she’s shatting on her uppers. She figures the peeper can get her some dough,” is anybody’s guess. Somehow they cope.

¤

The fact is, it’s rare, if ever, that we read a book and understand every single word, every literary allusion, every local or historical reference, just as we don’t understand every single thing we encounter as we go about our lives. And, of course, with fiction it gets harder depending on the age of the work and our cultural distance from its milieu. In a piece on John Updike’s Rabbit Is Rich (1981), Martin Amis writes, “Like its predecessors, the novel is crammed with allusive topicalities; in a few years’ time it will probably read like a Ben Jonson comedy.” I imagine there may be readers of that essay who could use a little annotation explaining the nature of Ben Jonson’s comedies.

If the common reader happily misses a few references, we tend to take it for granted that the best literary works will require explanations, glosses, and readers’ guides. Many have read James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) with a map of Dublin, Ireland, and a copy of Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce’s Ulysses (1988, by Don Gifford with Robert J. Seidman) close at hand. Joyce would have been delighted.

Steven C. Weisenburger’s A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion: Sources and Contexts for Pynchon’s Novel (1988) is a great help in understanding much abstruse material in Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 masterwork; although, when I laid hands on the compendium (a good decade after I’d first read the novel), I was thrilled to find that he’d got various things wrong, including not knowing the English meaning of “minge.” And this is one of the joys of annotated volumes: seeing what the editors did and didn’t explain.

And it doesn’t stop at high literature. There’s a subgenre of annotation that seeks not to explain evident difficulties, but to show the complications in apparently uncomplicated texts. Martin Gardner is the boss here. Having annotated Lewis Carroll’s Alice volumes (and declared Carroll to be sexually “innocent”), he went on to annotate books by G. K. Chesterton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), and Ernest Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic — Sung in the Year 1888” (1888). His publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, runs a list of annotated volumes that includes The Annotated Little Women (2015), The Annotated Peter Pan (2011), and The Annotated Wizard of Oz (2000). Do these works need annotation? The question is moot, since there’s clearly a market and an audience; and if we’ve learned anything in the last several decades, it’s that scholarship can be applied to popular, or even low, culture, just as successfully as it can be applied to high art.

¤

Raymond Chandler would have understood the dichotomy and might have reveled in the contradictions as they applied to his own work. In writing for a pulp audience, he knew he was slumming, inhabiting the less respected and less examined districts of the city of words. But he was not modest about his talents or his ambitions. He’d had an English classical education at London’s Dulwich College, which contained Marlowe House. He knew that his hero’s name might evoke Christopher Marlowe for some readers, but certainly not for all. The earliest version of Chandler’s detective is named Mallory, as in Thomas Malory, the author of Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), but maybe he came to think that was going too far.

In a 1949 letter to Hardwick Moseley, Chandler wrote, “The aim is not essentially different from the aim of Greek tragedy, but we are dealing with a public that is only semi-literate and we have to make an art of a language they can understand.” His invocation of Grecian heights strikes me as going way too far.

¤

No doubt the “semi-literate” public will not be rushing to read The Annotated Big Sleep, but for the rest of us, there’s a huge amount to enjoy in the book. I found myself more intrigued by the background information than by the editors’ close reading of the text, which sometimes feels like they’re breathing over your shoulder and making arch remarks, telling you how to read (for example, “Carmen is back to her default between the kitten and the tiger — for now”), but no doubt some readers will feel the opposite way.

Some of this background comes into the “who’d have thought it?” category. For instance, we’re told that in the 1930s, Los Angeles had 300 casinos and over 40 newspapers; hard to say which of those numbers is more surprising. Information about the city’s population and ethnic makeup is fascinating. I don’t think many of us regard 1930s Hollywood as the center of Jewish life in Los Angeles. The book quotes the journalist Garet Garrett (not his birth name), who visited the city in 1930 and wrote,

you have to begin with the singular fact that in a population of a million and a quarter, every other person you see has been there less than five years. More than nine out of every ten you see have been there less than fifteen years.

In 1939, the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration authored a book titled California: A Guide to the Golden State. In it, they called Los Angeles the “fifth largest Mexican city in the world” (a distinction that nowadays belongs to Chicago). We also learn that between 1920 and 1930, 30,000 Filipinos migrated to California. They were known as dandies and sharp dressers, which explains Marlowe’s line to Carmen Sternwood that she’s “[c]ute as a Filipino on Saturday night.” I guess this is a racial slur, but as these things go it seems quite gentle.

There are some revelations relating to Marlowe himself — details that are easy to miss or simply skim over. For instance, Marlowe’s description of himself on the novel’s first page, “I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it,” is army slang — “neat, clean, shaved and sober” means ready for inspection. Later, in a description of Marlowe’s apartment, we read he has “an advertising calendar showing the Quints rolling around on a sky-blue floor, in pink dresses.” I had never thought to wonder who the “Quints” were, but we’re told these are the Dionne quintuplets, identical French-Canadian girls born in 1934, the first quintuplets to survive past infancy. A couple of them are still alive, if Wikipedia is to be believed.

There’s also an interesting consideration of Marlowe’s daily rate — $25 plus expenses, which some clients find a bit pricey. It’s the equivalent of $400 in today’s money, which sounds a tidy sum, although considering what Marlowe has to go through to earn his money, it’s not altogether unreasonable.

The annotations make much of the geographical and topographical background to the novel, describing Laurel Canyon, the Pacific Coast Highway, Franklin Avenue, and noting landmarks such as the Sunset Towers and Bullocks on Wilshire. But as becomes obvious to anyone who’s tried to walk in Marlowe’s footsteps (something I did when I first started living in Los Angeles), one of Chandler’s skills was to blend a detailed real city with one of his own invention. So yes, being told that Geiger’s bookshop is on Hollywood Boulevard by the corner of Las Palmas seems utterly precise, but Stanley Rose, who had a bookstore at more or less that location, isn’t much of a model for Geiger: you’d find Rose hanging out in his store talking with Hollywood literati rather than taking nude photographs of drugged heiresses. At other times, Chandler simply made up the names of streets; Laverne Terrace and Alta Brea, for example, sound completely authentic, but you won’t find them on any map.

The editors, inevitably, and reasonably enough, wade into the inscrutable and contested sexuality of Chandler and Marlowe. I’ve never been sure whether Marlowe’s homophobia (as Chandler wouldn’t have called it) was his own, or Chandler’s, or simply something that pulp readers would have expected from a tough guy detective. It’s well known that quite a few people who met Chandler assumed he was gay, but that raises more questions than it answers, and there’s certainly no evidence that he ever had any sexual relationships with men. Still, the annotations are interesting in themselves. They tell us that the “1920s and early ’30s saw no fewer than ten new terms for ‘homosexual’ recorded,” including “queer.” We also learn that, as a result of prohibition, gay and lesbian subcultures had become more accepted in select quarters, while still remaining hidden. Once you were breaking the law by drinking illegally in clubs and speakeasies, you were less likely to cut up rough about seeing some same sex couple and a drag act or two.

The editors also raise the possibility that when Vivian Sternwood, wearing a “mannish shirt and tie,” says to Marlowe, “I was beginning to think perhaps you worked in bed, like Marcel Proust,” she may be accusing him of being gay. I don’t quite buy that, but then, I don’t have to.

I do buy, eagerly, the book’s analysis of the instances where Chandler “cannibalized” his own early stories and incorporated them in the novel. They show, despite Clive James’s insistence to the contrary, that Chandler’s writing improved very rapidly indeed in the six years between the publication of his first short story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot” (1933), and The Big Sleep (1939).

The book is illustrated with dozens of images, book and magazine covers, movie stills, maps, period photographs. These are well chosen and very useful. I wish some of them were bigger, especially the maps, and I wish some of those pulp covers were in color, but you can’t have everything.

For what it’s worth, I only found one error, maybe half an error. The book has Le Corbusier as sole designer of the chaise longue basculante: these days Charlotte Perriand is usually given her due as co-designer.

The book’s bibliography is lengthy without being exhibitionistic, and the editors have even managed to track down a treatise on “the lost art of walking,” by one Geoff Nicholson, that contains a short section about Chandler. Top-notch sleuthing. Marlowe would be proud.

¤

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His latest novel, The Miranda, is out now.

The post “Marlowe Would Be Proud”: On “The Annotated Big Sleep” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2A54PBv

0 notes