#although re-reading your question.... are you perhaps playing a translated version??

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I'm kinda confused... In the main route, Mychael doesn't know yet if what he's feeling is love (that's what I think based on the last posts). But in 2 of the bad endings (the one that MC kills Mychael and the other where you are hypnotized by Mychael to stay with him forever), he says things that make us think he already knows he loves us. For example: "At least I'm dying by the side of someone, I'd like to hear your voice" or "I'm sorry, I wish I could know the way you are or that you'd love me the way I am" (I don't quite remember the quotes but they are something like this), and it ends saying "You love Mychael. Mychael loves you. You two live happy".

It makes me think... Mychael being placed in a dangerous situation where MC does not accept him the way he is, makes he know he loves her? What does it change? Actually, have I understand everything wrong? He does not love her in those endings, he's just desperate for companionship?

The last line of your question already answers it!

In Ending 2: You Monster, when he says that, he's comforting himself in his last moments knowing he's not dying alone. In Ending 3: Playing Pretend, when the narration says those lines ("You love Mychael. And he loves you.") he only thinks he knows what love is in his desperate attempt to convince you that everything is fine. In reality those words are empty, only serving as fodder to fill your head. In his eyes what he's doing with you (living together, spending time together and doing things together) equals 'love' when it's far from the truth. Especially considering he's puppeting your actions the whole time. He was just,,, a little,,, desperate,,,

#mushroom oasis vn#mychael ask#he was NOT cooking with that one#go back in the kitchen mychael smh#although re-reading your question.... are you perhaps playing a translated version??#because i dont recall some of the lines hmm

400 notes

·

View notes

Text

[TJLC] Distracted by AGRA (or the many hints about personification of death in The Six Thatchers)

PLEASE CONSIDER THIS A WORK IN PROGRESS. IT’S NOT PERFECT BUT I HAVE SOME GOOD IDEAS HERE, I THINK, SO KEEPING IT FOR NOW.

A FEW DISCLAIMERS: - I’m not a native English speaker and this wasn’t betad, so excuse the less-than-perfect English (although you’re about to find out what native language actually is). - I’m very new in the fandom and in reading/writing meta, this would be my second meta post tbh, so excuse the amateurism. - Everything I’m about to write here is based on very quick and easy Google searches. I’m BY NO MEANS AN ACADEMIC! I’m not well versed enough in any form of literary analysis to claim more than that, but perhaps this post will be a breeding ground for new ideas. If you are an academic and you find these interesting - please go ahead and expand on them. - Lastly, this may have been picked up before by other meta writers and if so - I’m not aware of it, as I’m quite new to this fandom.

tl;dr: The Six Thatchers seems to be full of hints about the personification of death and cultural/religious representations of it, in a way that may even hint that that Mary = death, and/or that Moftiss were very preoccupied with the idea while writing it. It should be noted that I find these tidbits interesting in the context of well-established TJLC theories I’ve been reading up on a lot lately, namely EMP and M-Theory. I found these details interesting in the context of reading TST as something that’s happening in Sherlock’s MP as he’s dying and suspecting that Mary is dangerous and perhaps even linked to Moriarty.

AGRA > Samarra > The Four Angels of Death

As these things always go, I’ve been re-watching episodes while researching my WIP fic ‘Turned’. I have this new habit these days of only listening, instead of actually watching the episode in search of a fresh perspective. This time I was blown away, once again, by Sherlock and Mycroft’s conversation about AGRA. It’s a VERY odd conversation considering the topic, and what caught my ear this time was Mycroft mechanically reciting facts about the city of Agra. Why Agra, I asked? What’s so important about it? Nothing, the way I see it. One search led to another and I looked up Samarra, thinking perhaps I’ll find some connection between the two cities, but couldn’t.

The search for Samarra and the parable about it led me to the Appointment in Samarra wiki page, which mentions that the title of the book comes from a retelling of an ancient Mesopotamian tale by W. Somerset Maugham (the source of the next quote is here):

"The Appointment in Samarra" (as retold by W. Somerset Maugham [1933])

The speaker is Death

There was a merchant in Bagdad who sent his servant to market to buy provisions and in a little while the servant came back, white and trembling, and said, Master, just now when I was in the marketplace I was jostled by a woman in the crowd and when I turned I saw it was Death that jostled me. She looked at me and made a threatening gesture, now, lend me your horse, and I will ride away from this city and avoid my fate. I will go to Samarra and there Death will not find me. The merchant lent him his horse, and the servant mounted it, and he dug his spurs in its flanks and as fast as the horse could gallop he went. Then the merchant went down to the marketplace and he saw me standing in the crowd and he came to me and said, Why did you make a threating getsture to my servant when you saw him this morning? That was not a threatening gesture, I said, it was only a start of surprise. I was astonished to see him in Bagdad, for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.

There is also a very interesting study guide link from this website, which asks some very interesting questions about tale, such as Maugham’s decision to make Death a non-omniscient narrator of this tale, as well as a woman. I’ll return to Death being referred to as a woman later. However, since I have no expertise in literary readings, I’ll leave it to others who might be to add some more here.

More below the cut:

The version of the story in TST is a bit different; the servant is absent from the tale; it is instead the merchant who has the nighttime appointment with Death in Samarra after being startled to see Death that morning in the Baghdad market. (This note was taking from a wikipedia entry about another - apparently- very deterministic play by Maugham, Shepey.)

Anyway, the Appointment in Samarra wikipedia mentions that Maugham’s story comes from a much older version recorded in the Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 53a.

The Talmud is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism. I’m a Hebrew speaking Jew, though an atheist one who isn’t well-read in religious texts at all, but I was intrigued enough to look up the Hebrew Talmud version of the text (in fact it’s originall in Aramaic, but wikipedia offers a Hebrew tranlsation). A quick Google search led me to the wikipedia page about the personification of death, and that’s when things got interesting.

Under the section about the grim reaper in Judaism, a story from the Talmud is mentioned, which seems to be another version of the Appointment in Samarra story. Here’s the story, translated by Google Translate, because I couldn’t find an English version:

The Babylonian Talmud tells of a sage, Rabbi Bibi, the son of Abiy, whose angel of death was often in his company. Rabbi Bibi heard the angel of death ask his emissary to name a woman named Miriam (Mary) who was a hair dresser (the future mother of Jesus). The messenger of death accidentally killed another woman named Miriam (Mary) who was a teacher. The angel of death said to his messenger: "I asked you to kill Miriam the barber and not Miriam the teacher." The messenger of death replied: Then I will bring Miriam the teacher back to life and bring before you Miriam the barber. The angel of death said to him: If you have already brought Miriam the teacher, leave her with me along with the rest of the dead. The angel of death asked his messenger: How did you manage to kill the teacher Miriam even though it was not her time to die? The messenger of death replied: She was killed before an opportunity to kill her - she was fiddling with the stove with ember in her hand to clean the stove. Inadvertently she caused a burn in her leg - and when a person was harmed and his determination of his time to die was undermined - so I had a chance to kill prematurely. The sage, Rabbi Bibi, asked the angel of death: Do you have permission to kill people before their pre-determined time has come? The angel of death answered, "Yes, for it is written, 'There is no one who has perished without judgment.'

(According to wikipedia, this story is taken from תלמוד בבלי, מסכת חגיגה, דף ד, עמוד ב – דף ה, עמוד א).

AGR(A?M?)

Alright, I said, two Marys, escaping death but then meeting it eventually. It happens.

But as I read on… that Hebrew wikipedia page mentions another personification of death, the angel of death Azarel. Azarel has three ‘colleagues’ (e.g archangel) in Islam (and in some variations, they also exist in Judaism and Christianity): Jibrail (Gabriel), Israfil, commonly thought of as the counterpart of the Judeo-Christian archangel Raphael, and Mīkhā'īl (Michael).

So wait, that’s -- that’s Azarel, Gabriel, Raphael... as in AGR(A)? Whoa. That fourth angel mentioned in Islam is Michael - which doesn’t hold up with AGRA - but could that be a coincidence? We’re told two things about BBCSh’s AGRA, but we can’t really know they’re actually true. The first one is that Mary claims it’s her initials, which we later learn is possibly not true - John gets mad realizing it’s another lie. The other thing is that Mary claims to be ‘R’, for Rosamund, but we can’t be sure about that either. However, another cool detail: in Christianity, Raphael is generally associated with an unnamed angel mentioned in the Gospel of John, who stirs the water at the healing pool of Bethesda. Yes - I know, the M really doesn’t fit there, but M really is a character that stands out in the BBCSH universe, doesn’t it?

Moving on to more cultural references of the personification of death the Hebrew wikipedia page offers, note that I haven’t read the first and it’s been years since I watched the second:

Death with Interruptions

In Death with Interruptions by José Saramago, they mention, death is a woman, and she falls in love with one of her future victims. She decides to spare his life: Every time death sends him his letter [notifying him of his imminent death], it gets returned. Death discovers that, without reason, this man has mistakenly not been killed. Although originally intending merely to analyse this man and discover why he is unique, death eventually becomes infatuated with him, so much so that she takes on human form to meet him. Upon visiting the cellist, she plans to personally give him the letter; instead, she falls in love with him, and, by doing so, she becomes even more human-like.

Chess and The Seventh Seal

Another reference is the film The Seventh Seal, about a knight returning from a crusade, and discovers his land his ravaged by plague. The knight encounters Death, whom he challenges to a chess match, believing he can survive as long as the game continues. Does that remind you of any particular promo pics?

What I find interesting in all these references, is that they all seem to deal with questions regarding ‘dealing with death’ that, in the context of EMP for example, can be seen as Sherlock ‘running simulations’ (or asking philosophical questions) on how to deal with his current situations:

- ‘Do you have permission to kill people before their pre-determined time has come’? (Can people time die before their pre-determined time? Can people escape pre-determined death?)

- Can you interrupt death with love? Was Mary supposed to kill John, fell in love with him and thus his death was postponed? Is John still in danger?

- What can one do to postpone death - perhaps challenging it to a game, hoping for survival as you distract it?

Tagging other meta readers/writers who I think might enjoy this ; let me know if you don’t - I won’t tag you again): @sarahthecoat, @devoursjohnlock @inevitably-johnlocked @possiblyimbiassed @waitedforgarridebs @tjlcisthenewsexy @loudest-subtext-in-tv @therealsaintscully

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books and Mirrors: As A New Year Dawns

The month of Elul, the last month of the Jewish year, is well known as the traditional time for reviewing the year, reflecting on our behavior and general comportment, owning up to our shortcomings, and finding the resolve to face the season of judgment, if not quite with eager anticipation, than at least with equanimity born the conviction that we can and will do better in the coming year. You often hear the Hebrew phrase ḥeshbon ha-nefesh, literally “an accounting of the soul” in this regard—and those words really do capture the concept pithily and well: thinking of our lives as ledger-books in which our instances of moral courage and ethical inadequacy stand in for the accountant’s credits and debits works for me and will probably suit most. There is even a book with that title—Sefer Ḥeshbon Ha-nefesh by Rabbi Menaḥem Mendel Lefin, written in 1808 and the only rabbinic work known to have been directly influenced by the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin—which I wrote about to you all a few years ago just before Pesach. (To review what I had to say there, click here.)

How exactly to go about this is a different question, however. I suppose some people really can just sit down and review the year week by week, noting where they personally feel themselves to have come up short and resolving to respond in a way more in keeping with the moral code they claim to espouse when facing analogous situations in the future. For most of us, though, that process—although theoretically possible—is not that practical an approach to the larger enterprise: who can remember the days of our lives with clear-eyed enough exactitude to analyze deeds from months ago with the certainty that we are remembering things precisely correctly? Fortunately, there are other ways to see ourselves clearly and for many, myself included, the simplest answer is to use a mirror. Not a real one, of course, in which you can only see the reflection of your outermost appearance. But there are other kinds of mirrors available to us, some of which have the ability to reflect the inner self and which can serve, therefore, more like windows into the soul than the kind of mirror you look into each morning when you brush your teeth and see yourself looking back with a toothbrush in your mouth.

For me personally and for many years now, that mirror has always been a book I’ve chosen to read or re-read during Elul in the hope that it will allow me to see myself reflected either in its plot, in the way some specific one of its characters is depicted, or in the world it describes. Over the years, I’ve chosen well and less well. But when I do somehow manage to choose the right book for Elul, that choice makes all the difference by allowing me to see myself in the depiction of another far more clearly than I think I ever could have managed on my own.

This year I read Marcos Aguinis’ novel, Against the Inquisition. Although the author is apparently very well-known in his native Argentina and throughout the Spanish-speaking world, I hadn’t ever heard of him until just this last July when Dara Horn published a review of the new English-language translation by Carolina de Robertis of his most successful book, called La Gesta del Marrano in Spanish, in Moment magazine. The review was stellar (to read it for yourself, click here) and left me intrigued enough to buy a copy with the intention of it being my Elul book for this year. It wasn’t a big investment, so I wasn’t risking much. (Used paperback copies and the e-book version are both available online for less than $5 each.) But it turned out to be exactly the right choice: I just finished it earlier this week and found myself truly astounded both by the author’s literary skill and, even more so, by what the book has to say about the nature of Jewishness itself.

Seeing myself in the protagonist, Francisco Maldonado da Silva—a real historical figure who lived from1592 to 1639—was simple enough. Imagining myself reaching the level of piety, self-awareness, courage, and moral decency he exemplified in his life and, even more so, in his death—that was the mirror into which I found myself peering as I read Aguinis’s book. I don’t have to be him, obviously. But I do have to be me. And so the question is not whether I could learn Spanish and move to the seventeenth century, but whether I have it in me to be me in the same sense that the book’s protagonist was himself. If the concept sounds obscure when I formulate it that way, read the book and you’ll see what I mean: I can hardly remember feeling more personally challenged by a novel, and more eager to accept the protagonist as a moral role model. Against the Inquisition is a historical novel, of course, not a non-fiction work of “regular” history. But it tells a true story…and the opportunity to read the story, to take it to heart, to be moved incredibly by its detail, and to feel transformed by the experience of communing with a great Jewish thinker through the medium of his art—that is the gift Against the Inquisition offers to its readers.

The plot, fully rooted in the real Francisco Maldonado da Silva’s life story, is beyond moving. The details of Jewish life in Latin America in the late 1500s and the early 1600s will be obscure to most readers in North America today. But the short version is that all of South America except Brazil was part of the Spanish Empire back then. And the Catholic authorities (whose power over the region’s secular rulers was almost absolute) were dedicated not merely to making the practice of Judaism illegal, but to ferreting out even the vaguest traces of Jewish practice of belief that might still be lingering among the so-called “New” Christians, the descendants of those Jews who chose conversion to Catholic Christianity over flight when the Jews were exiled from Spain and Portugal, but at least some of whom retained a deeply engrained sense of their own Jewishness intact enough to pass along to their children and their children’s children as well.

Da Silva’s life story as retold in the book is remarkable in almost every way. His father, a physician harboring a deep, if secret and entirely illicit, devotion to his own Jewishness is eventually discovered and punished so cruelly and so degradingly that it beggars the imagination to consider that his torture—which is certainly not too strong a word to describe his treatment—was undertaken by men who considered themselves not only deeply religious but truly virtuous. But the meat of the novel is the story of how exactly the physician’s son Francisco, who also becomes well-known and highly respected doctor, is made aware of his Jewishness and then finds it in him not to dissemble so as not to be caught, but, at least eventually, to embrace his Jewishness and his Judaism openly and fearlessly. That kind of behavior was not tolerated in Spanish America, and the consequences for Francisco are, at least in some ways, even worse than the physical abuse and public humiliation to which his father was subjected.

The last chapters particularly are seared into my memory. You know what’s coming. You know that there’s no other way for the book to end. You understand that the protagonist, Francisco himself, sees that as clearly as you do. And yet you continue to hope that you’re wrong, that some deus ex machina will descend from the sky and make things right. You know you’re being crazy by hoping for such a thing—and, if you are me, you already know that the auto-da-fé of January 23, 1639, in Lima, Peru, was perhaps the largest mass execution of Jews ever undertaken by the Catholic church, a nightmarish travesty of justice undertaken in the name of religion in which more than eighty “New” Christians were burnt alive at the stake for the crime of having retained some faint vestige of their families’ Jewishness—but you continue to delude yourself into thinking that perhaps the author will take advantage of his novelist’s prerogative to just make up some other ending. That Francisco is depicted as having the means of escaping his prison cell but instead uses his freedom to visit other prisoners and encourage them to embrace their Jewishness and to accept their fate with pride and courage—that detail alone makes this novel a worthy Elul read.

My readers all know who my personal heroes are. Janusz Korczak, who chose to die at Treblinka rather than to abandon the orphans entrusted to his care. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who returned to wartime Germany to preach against Nazism and eventually to play a role in the plot to assassinate Hitler, for which effort he paid with his life. And now I add Francisco Maldonado da Silva, who chose to die with dignity and pride as a Jew rather than to run off and spend his life masquerading as something he was not and had no wish to be. Could I be like that? Could I live up to my own values in the way these men did? Could I be me the way they were them? I ask these questions not because I wish to answer them in public, but merely to show that they can be asked. They can also be answered, of course. And that is what Elul is for: to challenge us to peer into whatever mirror we choose…and ask if the man or woman we could be is looking back, or just the woman or man we ended up as. That is the searing, anxiety-provoking question the holidays about to dawn lay at our feet. If you’re looking for the courage to formulate your own answer, read Against the Inquisition and I’m guessing you’ll be as inspired to undertake the ḥeshbon ha-nefesh necessary to answer honestly as I was.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

FF8 Translarison, Part 1: Back to... university?

Hello everybody and welcome to the first part of my comparative look at the English and French translations of Final Fantasy VIII! And yes, I have decided to call it “Translarison”. Because it's a TRANSLAtion compARISON, you see. BTW, I shall use “Translarison” as a tag if you want to search for these specific posts more easily.

The main reason why I wanted to do this was that, being French, I obviously grew up with the French version of the game but a few years ago, out of curiosity, I played through the game in English after hearing about some minor differences, and discovered that there were a lot more than what I'd been told, to the point that certain characters, scenes and even subplots come across completely differently.

On top of that, I just found some of the different choices in translation conventions very interesting, and possibly quite telling of cultural differences, so comparing the two fascinated me.

I also found it interesting that in some aspects, the French version seems to be based off the original Japanese scripts, yet in others, it seems too close to the English one to be a coincidence. It's weird, to the point if I wonder if the translator(s) used both versions as sources (assuming the English translation was already finished while the French one was being worked on). But then, there are also a lot of things that don’t match either (especially when it comes to names), so it’s also interesting to see when the translator took some liberties.

Gonna tell you now, maybe it's just out of nostalgia but overall, I do prefer the French one as the characters generally come out better in my opinion, but there are parts where I like the English one better, and I will of course point those out.

Now, let me explain how I intend to work on this thing. Although this is sort of a Let's Play as I will go through the game and comment on it, it won't be a complete one as I will focus specifically on translation differences and analyse the most interesting ones (as it would get tedious to do so for every line of dialogue where all I'd have to say is “they pretty much say the thing, except in French), so I will skip around. I may give my opinions on random moments from the game if I feel particularly strongly about them, but like I said, it won’t be the focus. If you do want to know my thoughts on every bit of the game, you can read a more traditional Let’s Play I wrote here: http://officialfan.proboards.com/thread/536741/french-version-final-fantasy-finale

I do intend to be as thorough as possible and highlight stuff from side-quests, but obviously I won't be able to cover everything considering there are parts where you need to split the party up and you can't change it until way later. Hm... maybe I could go through those again with different configurations as bonus content. NOT A PROMISE.

It is also important to note that I am an amateur doing this for fun. I apologize in advance if some of my interpretations are a bit off. I can however guarantee that my schedule will never slip as my schedule is “whenever I feel like it”. Keep in mind I'm doing this on my free time and it takes a lot of time to go through it, especially since I have to go through it twice for this.

One last thing before we begin: do not hesitate to ask questions. I just realized I didn't have an “ask” button active on my blog, so I activate just for this, but of course you can also ask me stuff any other way you'd like. Oh, and feel free to request me looking at specific stuff from the game. As much of a ridiculous fanboy as I am for this game, even I don't remember or know everything about it (which is why it remains so fascinating so many years later!), and I probably won't think of re-visiting locations on my own if they aren't tied to a side-quest.

Right, that's enough blabbering, let's get to the actual game!

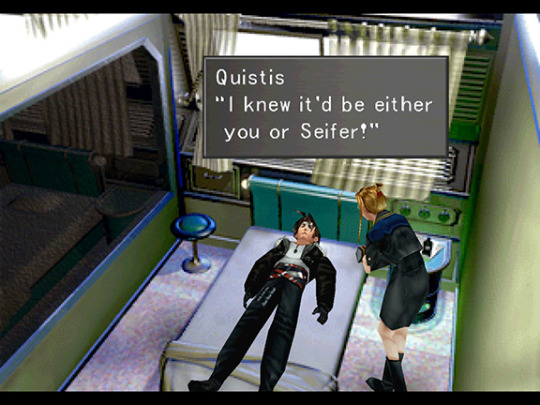

Nothing to say about the opening cutscene as it is still in English even in the French version, so let’s head straight for the infirmary. Not much different so far, though I do find this bit interesting. When Quistis arrives, in the English version, she says:

But in the French version, she says:

Which translates to “Good lord! I knew it would end badly”. You get the same idea in both versions, that Quistis is used to Squall and Seifer fighting and getting into trouble, I just find it interesting that one version chose to specifically name the characters, whereas the other chose to focus more on Quistis lamenting her students’ behaviour. I should also point out that logically, Quistis must have picked up Seifer first, so the French version makes a bit more sense because, well... of course you knew it’d be him, you must already be aware of what happened.

Also, note how the French version doesn’t have quotation marks. While I think it looks better without them, I can see why the English version does that as it shows more explicitly that the names aren’t part of the dialogue.

The conversation between the two in the hallway is very similar in both versions but there is one thing I find funny:

There’s a line in the English version where Squall says “I am more complex than you think” which is pretty much word-for-word the same in French, but Quistis’ reaction is different. In the English version, she just asks him to tell her more about himself, while the French one, she uses the above line. You see, “complexé” is a word that pretty much means “hung up”, so she’s teasing him about his attitude.

I really like this dynamic between the two because whereas the characters’ angst is usually glorified in other FF games, here Quistis is seeing right through him (with her Laser Eyes!) and is having none of his crap. Also, it’s one of the few times the characters are being a bit more rude than in the English one. Not that Quistis is really being mean, but you get the idea.

On an unrelated note, I never noticed it before but as they pass by, there’s a dude who checks out Quistis and two girls look at Squall and then giggle to themselves. I love little details like that.

Next, we get to the classroom. Still only minor differences, like Quistis saying that “it won’t be a surprise to anyone” that the field test is this afternoon whereas the English version has her mention there have been rumours, which kind of implies that they just drop on the kids that they’re gonna partake in a genuine battle at the last minute.

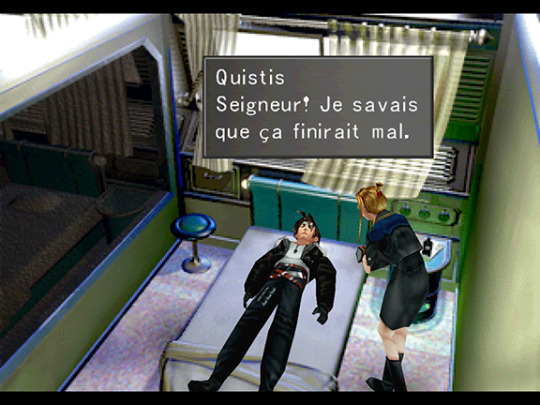

As any seasoned FF8 player knows, the first thing to do is to pick up our trusty Guardian Forces, Shiva and...

... Golgotha?! Yes, here is the first renaming of the game. Give it a round of applause! It’s an odd one, seemingly a reference to the hill Jesus of Nazareth was crucified on. I guess it’s because the creature has a vaguely crucifix-like shape when it spreads its wings. I have to admit Quetzalcoatl is more fitting as it is a reptilian-looking flying creature, so it’s close to a winged serpent, but I guess Golgotha is less of a pain to pronounce, and it actually fits with the character limit.

Not much else of note aside from the fact that in the Garden Square forum, Almasy is misspelled as Almassy. And considering how much of an ass Seifer is, it seems fitting. Also, one of the students uses the initials J.I in the English version whereas they use O.S. in the French one, and I don’t know why.

Quistis tells us to meet her at the front gate, we leave and bump into Selphie, setting up the romance between the two. Oh wait, no. Don’t know if it was intentional, but I always loved that they played with the old “bump into each other at school” cliché by NOT having the two characters get romantically involved. And it goes to show how overdone it was that even my 11-years-old self was aware of it.

I prefer when Squall is slightly less antisocial so I have him give Selphie a short tour of Balamb Garden University. Yes, Balamb Garden University. In what is in my opinion one of the more interesting minor changes, the Gardens are referred to as universities. And although the other two retain their original names, B-Garden is indeed known as Balamb Garden University (and yes, they keep the name in English), or BGU for short.

I realize that when you think about it, it doesn’t really make sense since they teach children below college age and in fact, considering the max age to apply for SeeD is 20, they wouldn’t have that many college-age students, but I like the more academic-sounding name. Come to think of it, Balamb Garden Academy would probably make more sense. Oh well.

Not that much different regarding the map but I wanted to show off the fact that even on pre-rendered stuff, the text usually is translated, which again is a nice attention to detail (although accents are omitted for some reason, which makes me think perhaps the graphics were updated using a non-European keyboard).

Well, time to look around good old Balamb Garden University. First stop, the quad (or campus, in French), for two odd changes. First, there’s a generic male student who explains that all members of the festival committee have been dispatched around the world. In the English version, he then explains that in spite of Selphie’s enthusiasm, it doesn’t seem likely it’s gonna happen:

But in the French version, he instead says that their task is to solve armed and political conflicts:

And on the same screen is one of the weirder changes. In the English version,Selphie asks Squall if he’s interested in what she’s doing. In the French one, though, she asks if he’s interested in her. But more bizarrely, in the French version, instead of the generic “Interested/not interested” choices, the first option is “a little bit (physically)”.

And in both versions, she then tells him that in that case, he should join the festival committee. Naughty French Selphie, using sex-appeal to get new members! But now, get ready to have your mind blown as we head for the cafeteria and we meet the Disciplinary Committee, because..

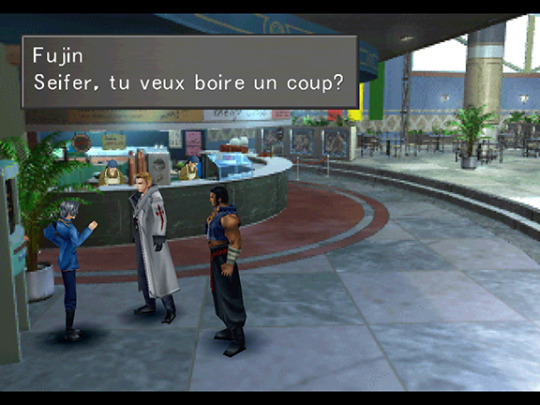

.

... French Fujin can actually use her adult words! In fact, pretty much none of the language tics found in the English version have made it to the French one, so Raijin doesn’t go “ya know?” all the time either and indeed, French Squall doesn’t say “Whatever” either.

And frankly, good riddance as far as I’m concerned. I assume it’s something the English translator(s) added and I hate it. It might be funny for five minutes, but it completely kills characterization and I hate losing development for the sake of “OH! HE SAID IT! IT KEEPS GETTING FUNNIER AND NOT ANNOYING AT ALL THE MORE YOU DO IT!”

But if you thought THAT was crazy, hold on to your underwear because here comes another bombshell:

BOOM!! Hot dogs have been replaced with pretzels! Or as we like to call it where they actually come from (and yes, I do live in France but my region also has them as a local dish), bretzels. With a B. Apparently, in the original Japanese, it was a special kind of bread instead. No idea how many more localizations there are. It’s a bit weird that they went with pretzels too, as it’s very specific to some areas of Europe, whereas hot-dogs are also famous here (which lends credence to my theory that the French version was made independently from the English one).

Anyway, take a minute to pick up the shattered pieces of your world and let’s continue. You know these faculty guys with their rice hats? Well for starters, they’re referred to as “templier” (which means “templar”) in the French version. Also, there’s one hanging around the library and when you talk to him, in the English version, he calls Squall a “problem child” whereas in the French version, he calls him “the famous Squall”.

I kind of like the English version a little bit more, if only for how bluntly tactless the guy is being (why, he’s almost as bad as Squall!), and yeah... “problem child” is putting it lightly.

Inside the library is another small change that I find amusing. You know this short-haired girl near the draw point?

Well, in the French version, she says she wishes they had “olé-olé” books, which... is a term that can’t really be translated directly but basically means “naughty” or “smutty”. So yeah, if you thought the English version was being too subtle for you when she said she likes “romance novels”, you can rest assured she absolutely means the Harlequin kind of “romance”.

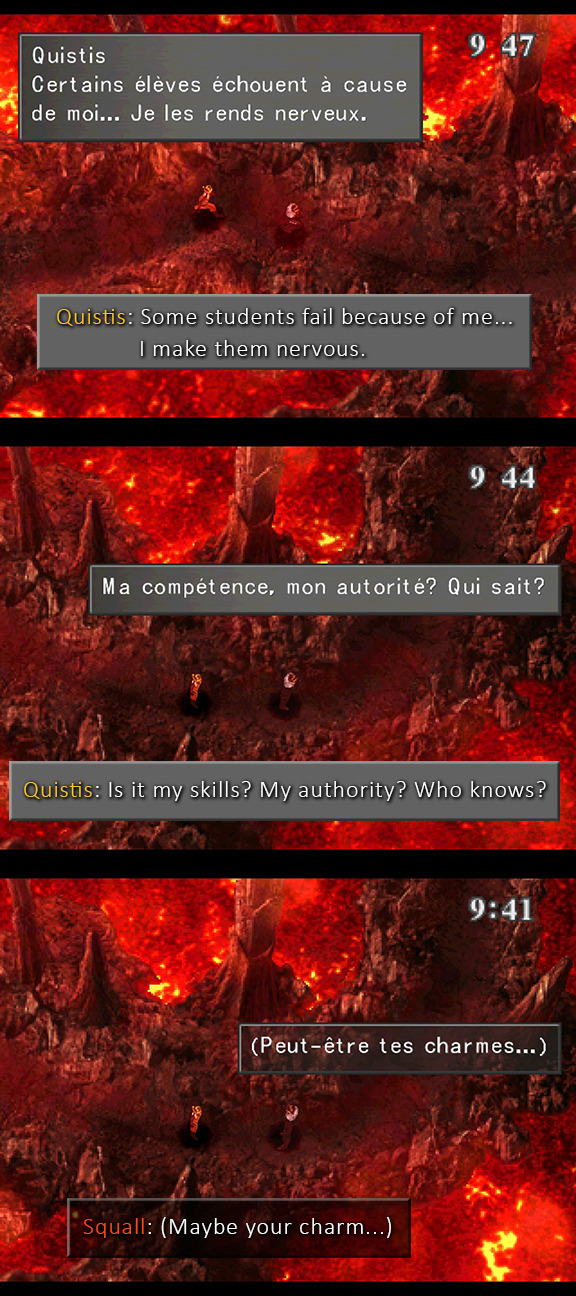

But enough lolligagging, let’s head for the Fire Cavern, which in French has become the Mines de Soufre, or Sulfur Mines. And here we already have one of the most interesting changes in the game. You know how in the English version, there is this dialogue:

Well, in the French version, it goes like this:

That’s right, the French version goes in a completely different direction, almost the exact opposite, in fact. Now, I remember reading that in the Japanese version, Quistis says something very similar to the English one and Squall thinks to himself “you’re a TEACHER”, meaning he doesn’t approve of how lightly she’s taking her role, so it’s probably a misinterpretation on the French translator’s part, but I love that version.

For starters, I think it speaks volume about Quistis. It highlights her insecurities about being a teacher, and students questioning her credibility due to her young age and lack of experience, while being oblivious to the fact that... yeah, being all alone with an attractive woman about their age , whose weapon of choice is a whip, would distract quite a few students. Hell, it seems to suggest she doesn’t even realize how absurdly beautiful she is. In every version, she deflects it by saying she’s only joking, but still, it seems there is more truth to it than she lets on.

But it also gives Squall more personality, showing that for his cold demeanour, he’s not a robot and he isn’t insensitive to an attractive woman’s charm,and he even shows a bit of a sense of humour. That shows a surprisingly large amount of layers on both characters for such a small bit of dialogue.

Also, the English version makes Quistis come across as more flirtatious, whereas the French one makes her seem more naive, despite her efforts to look like a tough instructor. And this shows one of the major differences between the English and French versions as the kind of romantic subtext between the two is very much downplayed here.

I like that a lot because while many people like to think that Quistis does have romantic feelings for Squall, or at least used to have some, I always found it very refreshing to have two fictional characters of opposite genders who work together and are just friends.

That’s not to say she wouldn’t question her feelings and whether or not they truly are platonic at some point, it seems unlikely that it would never come up, but I find the idea that her relationship with Squall is more friendly or sisterly a lot more interesting than yet another romantic sub-plot.

There isn’t really anything else to mention for the rest of the test so I think I’ll end this part here. And next time, we’ll be taking a look at the assault on Dollet!

I hope you all enjoyed this first part. Please feel free to comment and discuss and once again, do not hesitate to ask questions. Oh and if you liked it, a reblog would be nice to help spread the word. Thank you very much and see you soon!

#Final fantasy viii#FF8#ffviii#Squall Leonhart#quistis trepe#Selphie Tilmitt#Balamb Garden#BGU#University#translarison#French#English#Golgotha#quetzalcoatl#Guardian force#Ifrit#Shiva#Fire cavern#sulfur mine#character interpretation#Character Study

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Translation Process

An Interview with Sam Taylor, English author and translator of French contemporary authors, Leïla Slimani, Joël Dicker, Laurent Binet, to name a few.

The importance of translation

For as long as I can remember, be it in its original version or translated in the languages I knew (English and French) I have only memorized the name of the author of a work of prose or poetry I had chosen to read and couldn’t care less for its translator, if there was one. When I read such masterpieces as ‘The Name of the Rose’ by Umberto Eco or ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ by Gabriel García Márquez, I took the words at face value and never wondered who had translated them. Translators were the unknown soldiers of my life in reading.

Over the years I would eavesdrop on such passing information that a particular Shakespeare’s play production was worth a re visit at a theatre in Paris as it was enjoying a ‘new better translated version’… why so? I had been fine with the previous versions! Although I was aware of the importance of translation, I was still not interested in the human and qualitative aspect of it.

Only recently did I realize that the translator should not be ignored and that his/her work should be as much acknowledged and valued as the writer’s. Indeed, it requires specific skills that not all bilingual people possess and the responsibility is immense.

Nowadays , there is definitely a trend of awareness as talk shows on books highlight their names and invite them more often, they’re clearly quoted in books reviews, and more and more books blogs have entire sections devoted to books in translation. Thanks to Carolyne Lee, a member of MyFenchLife™ community and translator herself, I discovered Asymptote Journal, described as ‘ the premier site for world literature in translation’.Finally, specific prizes for best translated books abound, especially in the English speaking world (Best Translated Book Award, Pen Translation Prize ,etc.).

The art of translating French into English :

In that respect, when MyFrenchLife™ launched last month a book club of recently-translated award winning or best-selling French novels, as a facilitator, I delved deeper into my new role, and became fascinated by the translation process. In my research, I came across Sam Taylor’ name on many occasions and not only because he was also the translator of our first book on the list ‘The Perfect Nanny’ or ‘Lullaby’ by Leïla Slimani. He had already translated other major recent French novels. I found his site and contact. Nothing could stop me then from submitting to him a few questions, which he kindly answered.

An interview of Sam Taylor, translator of French novels into English

1. What is your preferred title, the UK or the US one and were it Lullaby, did you have your word to say for The Perfect Nanny?

The different titles of the book in the US and the UK reflect different visions of what kind of book it is, I think, and most of all how it should be promoted. I preferred Lullaby because it sounds more literary, and it reads like a literary novel to me. But Penguin US aggressively promoted the book as a thriller, and for that angle The Perfect Nanny probably works better. Leila Slimani was happy with that approach, so who am I to argue? As it happens, the book has been a huge success on both sides of the Atlantic, so perhaps the title didn’t make much difference. Or perhaps both publishers chose the right title for their market?

2. How long did it take you to translate this novel? Were you in contact with Leïla Slimani ? Did she give you any direction?

It’s a fairly short novel, so it probably only took me four or five weeks - I can’t remember precisely. I never even exchanged an email with Leila Slimani, which is unusual. I think I put a few questions in comments on the Word document and the editor asked Leila those questions directly; I’m not sure why. But she seemed very laid back about translation issues.

3. Is it absolutely necessary for a translator to read the whole narrative in the original language before translating or do you have a particular way to proceed?

I think it’s preferable to read the whole book first, but it’s not necessary and it’s not always possible. I doubt it makes any difference to the finished translation - it just means you make fewer wrong turns (like word choices, for example) during the translation process.

4. With such a powerful story, that echoes many of people's personal fears - what makes an apparently normal human being turn into the most atrocious murderer- was is not difficult to just execute your work, unbiased, instead of being the would-be reader-investigator that Leïla Slimani forces us to be after the first chapter revelations ?

I don’t think a translator has to be neutral towards the book they’re translating. In fact, passion is a plus. Part of what you’re translating is the indefinable spark that pulses beneath the words, and if the book doesn’t affect you emotionally it’s more difficult to render that spark into English. I don’t love every book I translate, of course, but it’s always more fun when I do. The biggest emotional reaction I’ve had to a translation was with Antoine Leiris’s You Will Not Have My Hate, which made me cry several times. And I loved translating In Paris With You, so I’m really glad you’re thinking of recommending that to your book group. It’s the best translation I’ve done, I think, and it was also the freest, because it’s verse rather than prose. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed translating it…

I’m translating Leila Slimani’s next novel right now, by the way: Dans le jardin de l’ogre (English title still to be decided). I think it’s going to be even more controversial than the last one was!

It’s a whole new wor(l)d

I could not be happier with Sam Taylor’s answers and be grateful for the time he spent writing them. They are not only shedding light on many of my interrogations on his work but they are also bringing me to the doorstep of a new territory in reading. I will probably never again take a foreign book for granted in my mother tongue.

#translation#english translation#leila slimani#the perfect nanny#lullaby#laurent binet#joël dicker#literature in translation#french literature#french contemporary#what to read#translation process#translator#french author#foreign literature#foreign languages#myfrenchlife#maviefrancaise#Paris#france

0 notes

Text

Game 352: Dungeons of Avalon II: The Island of Darkness (1992)

This screen is the same in both the German and English versions.

Dungeons of Avalon II: The Island of Darkness

Germany Zeret (developer); published by CompuTec Verlag (German) and Amiga Mania (English) Released in 1992 for the Amiga

Date Started: 7 January 2020

It was over three years ago that I played the frustrating Dungeons of Avalon (1991), which exceeded the typical diskmag game (a game that was distributed via an electronic magazine) in technical quality. But I wasn’t able to win it, first because the final battle was unbelievably hard–I can’t imagine anyone winning it “straight”–and second because even when I cheated to win the final battle, I couldn’t get any flag to trip to show me the endgame screens. Said screens did exist in the game, as attested by the various files.

So the ending was a bit of a downer, but the gameplay experience until then was very good, and we find the same experience in Dungeons of Avalon II. As far as I can tell, the game mechanics, graphics, and sound haven’t changed at all between the two versions. The only thing that’s changed is the layout of the dungeon and the ostensible reason for being there.

The German version supplies the backstory.

The games look a lot like Dungeon Master and indeed follow some Dungeon Master protocols when it comes to door switches and navigation puzzles. In everything else, however, they are much more products of the Wizardry lineage. In particular, enemies can’t be seen in the environment–you just stumble upon them–and combat is run by having each character specify an action and then watching as they execute in conjunction with the enemies’ actions. In their use of grotesque graphics and ambient sound, the Avalon games arguably exceed the best commercial Wizardry derivatives of the era.

I had expected to import characters between the games, so I was glad to see that the sequel starts things over with a new party. It takes place 49 years after the defeat of the Dark Lord in the first game. Avalon has become an empire and expanded to the sea and beyond. On one of its islands, evil has befallen the city of Isla. Monsters have appeared out of nowhere, overwhelming the trading port and slaughtering the city guards. The mayor, Roa, has written to the king for help. The king has dispatched several parties of soldiers and mages to the city, but none have returned. Finally, in desperation, he organizes one more small party, hoping they can succeed where the others failed.

The backstory specifies that “five heroes were chosen . . . two fighters and three magicians,” which conflicts with the fact that you can create a party of six and you’re not in any way limited by class. The races and classes haven’t changed. Races are human (mensch), elf, half-elf (halb-elf), dwarf (zwerg), troll, “gnom,” “lizzard” (echse), and “stembär,” the last an homage to music composer Rudolf Stember. Classes are fighter (krieger), thief (dieb), knight (ritter), hunter (jäger), monk (mönch), magician (magier), healer (heiler), and wizard (hexer), the last four equipped with spellbooks as well as melee weapons.

Creating a new character.

Once you specify race and class during creation, the game automatically rolls for intelligence, dexterity, wisdom, luck, strength, and constitution, modified by race. You can spend a lot of time re-rolling, but these attributes increase between 2 and 11 points per level anyway. Character portraits are automatic based on class and always seem to look human. All are male.

Even though I didn’t play with them–I never do–I noted that the default party starts at Level 3, which puts them at a major advantage over a party that you create yourself.

I went with:

Armin, a human knight

Fomorus, a troll fighter

Ferry, a half-elf thief

Jolson, a dwarf monk

Aurion, an elf magician

Taliesin, a lizzard wizard

I had a tough time getting things started. There are multiple German and English versions of the game on the web, some “patched” in some way, others not. I started with a WHDLoad version of the English edition, but halfway through Level 1 I ran into some problems–the same problems that a period reviewer found when he tried to play the game. It essentially had to do with the wrong encounters showing up in the wrong squares, making it impossible to pass those squares.

The shopowner is proud of his limited wares.

I couldn’t find any English version in which that problem had been repaired, so I switched to a “patched” German version (although I don’t know if that’s one of the things it patched), which meant starting over with new characters and losing a couple of hours of progress. Fortunately, the game is not that text-heavy, and I can read a lot of it without needing a translator, thanks to previous German RPG experience. Also, a lot of the text is in English even in the German version, including the title.

Not only is this encounter in the wrong place, he doesn’t actually give you a key.

There are 10 levels of 32 x 32 to explore (with worm-tunnel walls), divided into two structures: the dungeon and the Tower of Roa. (The first game had 50 x 50 levels, but fewer of them.) A menu town with a shop, a temple, and a training guild sits outside.

Exploration is not entirely “open,” but it’s less linear than the typical dungeon crawler. Each level has multiple sections, some disconnected from the others, and at any given moment you’re probably looking for at least three keys, objects, puzzle solutions, or other necessities to uncover different areas.

You have to check all walls for these little floor buttons. Pressing them removes the wall.

The levels also wrap, which always disappoints me. Wrapping dungeon levels give you a momentary navigation pause, but they otherwise offer little extra challenge to justify tearing the player out of any sensible reality.

My map of Level 2 of the main dungeon. Note the north/south wrap on column 6.

The levels are full of the types of light puzzles I remember from the first game. Small grates at the bottom threshold of the walls indicate secret doors; sometimes you have a dozen of these in a sequence. Other secret doors are revealed by pressure plates or wall switches. There are teleporters, traps, spinners, magic barriers, and occasional “ice floors” that send you careening down long hallways with no ability to stop. Fortunately, a group of spells keep you oriented and solve most of the navigation issues, including “Vogelblick” (“Birds’ View”) “Magier Auge” (“Magic Eye”), and “Falkenfeder” (“Levitation”).

The game’s automap is quite good, though not enough that I could rely on it exclusively.

Combats occur at fixed locations (with no respawning), but most have random compositions. Sometimes, you lose to two groups of three zombies, reload, and face a single skeleton on your second try. You don’t see the enemies themselves in the environment, but there are very feint blue lines on the tiles where a fixed combat is going to occur; whether this is intentional or some kind of side-effect of the game’s coding is unknown. Fighting follows a Wizardry model in which only the first three characters can attack in melee range. You specify actions for each character and watch them execute (threaded with the enemies’ actions) all at once. One nice thing is a “quick combat” option that just runs through the actions without narrating the results. At the end of combat (whether you win or flee), you get a little summary of who did and took how much damage, and how experience and gold were allocated. The only other game I remember ever offering such a feature is the German Legend of Faerghail (1990).

Combat options when attacking a “pest baby” include attacking, using an object, casting a spell, and defend.

The game strikes a good balance in difficulty. It allows you to save anywhere, but you can only camp (to recover health and magic points) on rare fixed squares that have an emblem with the letter “C.” You have to keep spell points in reserve to handle the occasional blindness, poison, disease, or petrification.

Final statistics after a battle with an “invisible.”

There’s been some nice ambient sound–creaks and groans and moaning wind as you explore the dungeon corridors. Unfortunately, it’s a bit repetitive and can’t be turned off independently from the music, which is well composed but (as always with me) unwelcome. Thus, I have been playing mostly in silence.

Perhaps the best part of the game is the grotesque monster portraits and other unusual graphics. The graphics are credited jointly to Hakan Akbiyik, Frank Matzke, and Klaus Ehrhardt. I’ve checked out their individual portfolios and don’t see anything quite the same as the Avalon games, so I’m not sure who to credit.

The authors’ conception of a “zombie.”

This dragon wants a “dragon stone.”

This “voodoo man” might be considered a little “questionable” today.

Unfortunately, the game has a lot of negative points, too:

1. I don’t care for the controls much. Too much depends on the mouse. You can move with the arrow keys but not activate doors or switches. Number keys open the characteristics of the characters, but you then have to use the mouse to switch to inventories or exit. When you’re given numbered commands on the screen, you can’t activate them with the number keys–you have to click on them. Things like that add up.

2. As with its predecessor, characters in Dungeons of Avalon II start hitting their level caps with two or three game levels left to go.

3. There might as well have been no economy. After you equip your characters at the beginning, the only thing to spend money on is the occasional temple healing and leveling up. For your first 4 or 5 character levels, you’re chronically under-funded and almost always waiting for enough gold to advance half your party. Pretty soon, the situation reverses and you have tens of thousands of gold pieces.

If you don’t get diseased or killed much, money doesn’t have a purpose.

4. It’s too goddamned long, particularly where the encounters leave you no reason to fight once you’ve hit the level cap except that all the encounters are fixed. A diskmag dungeon crawler of this skill would have been perfect at 12-16 hours. Instead, I think it’s going to come very near to 40.

As the game begins, you can enter either the dungeon on Level 0 or the Tower of Roa on Level 5. But the part of the Tower that you enter takes you only a short distance before you run into either locked doors or an encounter with a giant named “Argha” who wants you to bring him a dragon to grant passage.

You thus have to explore a while in the main dungeon. The game follows European hotel tradition by designating the first floor “0” and the second floor “1.” Level 0 is full of long, snaky corridors with a lot of false walls that have to be opened with switches. In the far southern corridor is a teleporter that takes you to a central area with four pressure plates (and four camping squares), the combinations of which determine which corridors are open at which times. The pressure plate is preceded by message squares that say “BEAM ME UP SCOTTY” in the German version but misspell “BEAM” as “BAEM” in the English version.

The northern half of the level is suggested as a “jail” with numerous cells curving off the main corridor, most hosting fixed combats. A guardian blocks the way to this area until you give him a letter of invitation, which is found in a treasure chest to the southeast.

Monsters on Level 0 are mostly giant turtles and giant frogs, neither of which has any special attacks. They ease you nicely into the combat system.

A freaky-looking turtle.

Two of the “cells” have special encounters. A dragon is looking for a “dragon stone” for some reason. A group of thieves offers to trade a key for their freedom, although I neglected to write down what I had to do to achieve their freedom. Their key ends up opening the “map rooms” in the Tower of Roa, allowing some further progression on its first level.

Some thieves complain about being locked up.

A teleporter brings the party to a long north/south corridor that leads to the stairs to Level 1. There, things get more complicated. A small, winding corridor leads you immediately to the stairs to Level 2, which you must nearly fully explore before you find stairs back up to Level 1.

The main part of Level 1 is presented as a rectangular hallway with six crypts jutting to the east and west. The crypts belong to royalty of ages past–kings and queens and princes of Avalon, Isodor, and the Isle Rachon. A couple of them are answers to later puzzles that otherwise block progress. One of the kings is given as the king of “ZD and CT,” which is I assume a reference to Zeret and CompuTec.

Zouth Dakota and Connecticut?

In a chest deep in the level, you find the first truly good equipment. Until then, you’ve mostly been stuck with the stuff you bought at the beginning, plus perhaps a few scrolls, potions, and regular missile weapons for the rear characters. Here, you find Arc’s Helmet and Ara’s Armour, Arc and Ara being heroes of ages gone. Mysteriously, you also find a few treasure chests that go into your inventory as whole chests. I’ve tried everything, and I don’t think there’s any way to open them. I think maybe you’re just expected to sell them whole.

What am I supposed to do with these damned chests?

I’ll stop there so I have something to talk about next time. I poured hours into this game over the weekend, hoping to finish it for a single entry, but it was to no avail. Cross your fingers and hope I can win this one.

Time so far: 24 hours

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/game-352-dungeons-of-avalon-ii-the-island-of-darkness-1992/

0 notes