#also you can tell this happened before Scott joined the Champions because that cast would be covered with signatures and drawings for him

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

As whump fan, I am very fond of this issue and the one preceding it. I always enjoy a good coma.

The art in this issue is lovely overall, but I'm not utterly sure those glasses are the best idea for a coma patient. I feel like they could be very easily dislodged. Also, this is probably a time for a gown rather than scrubs, as I don't think scrubs are supposed to go UNDER the cast.

As much as I've enjoyed Krakoa on a whole, I am a bit frustrated by the way so many plot threads got dropped to accommodate it. It makes a certain amount of sense, of course. Krakoa was such a big deal, a sanctuary where, flawed as it was in SO many ways, mutants could finally feel like they had a future. It makes complete sense that all the old grudges and pain were temporarily buried. But I am actually rather glad that From the Ashes seems to be at least something of a return to form. Even if Scott's name is infamous for other reasons, and there might be a new justification for a Schism, it gives me some small hope that some of those discarded plot threads might actually get resolved.

(Mostly I just really want a lot of people to realize that they've been a dick to Scott Summers, and give him an honest apology. But I'm biased.)

(All-New X-Men #08, 2016)

#scott summers#cyclops#hank mccoy#also you can tell this happened before Scott joined the Champions because that cast would be covered with signatures and drawings for him#lights out

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elvis, Truelove and the Stolen Boy: The Tragic Machismo of Nick Cassavetes’ ‘Alpha Dog’ by Amy Nicholson

[Last year, Musings paid homage to Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You’ve Never Seen, a review anthology from the National Society of Film Critics that championed studio orphans from the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the days before the Internet, young cinephiles like myself relied on reference books and anthologies to lead us to films we might not have discovered otherwise. Released in 1990, Produced and Abandoned was a foundational piece of work, introducing me to such wonders as Cutter’s Way, Lost in America, High Tide, Choose Me, Housekeeping, and Fat City. (You can find the full list of entries here.) Our first round of Produced and Abandoned essays included Angelica Jade Bastién on By the Sea, Mike D’Angelo on The Counselor, Judy Berman on Velvet Goldmine, and Keith Phipps on O.C. and Stiggs. Today, Musings concludes our month-long round of essays about tarnished gems, in the hope they’ll get a second look. Or, more likely, a first. —Scott Tobias, editor.]

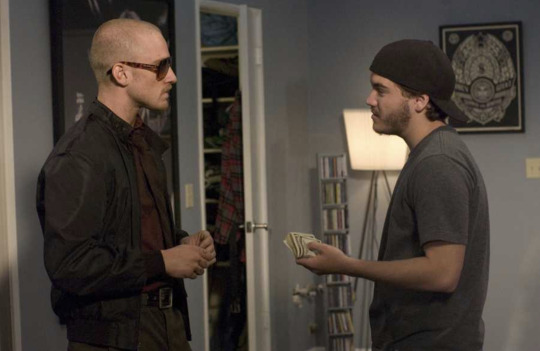

A decade before the presidency that elevated insults like “betacuck” and “soyboy” into political discourse, Nick Cassavetes made Alpha Dog, a cautionary tragedy about masculinity that audiences ignored. Time for a reappraisal. Alpha Dog is about a real murder. Over a three-day weekend in August of 2000, 15-year-old Zach Mazursky—in reality, named Nicholas Markowitz—is kidnapped and killed by the posse of 20-year-old San Fernando Valley drug dealer Johnny Truelove (Emile Hirsch) with a grudge against Zach’s older brother. No one thought the boy would die, not his main babysitter Frankie (Justin Timberlake), not the girls invited to party with “Stolen Boy,” and not even the boy himself, played with naive perfection by Anton Yelchin, who played video games and pounded beers assuming that his new captor-friends would eventually take him home.

Cassavetes’ daughter went to the same high school as Nicholas Markowitz. The murderers were neighborhood kids and he wanted to understand how fortunate sons with their whole lives ahead of them wound up in prison. The trigger man, Ryan Hoyt—“Elvis” in the film—had never even gotten a speeding ticket. Prosecutor Ron Zonen hoped the publicity around Alpha Dog would help the public spot the real-life Johnny, named Jesse James Hollywood, who was still on the lam despite being one of America’s Most Wanted. So the lawyers gave Cassavetes access to everything: crime scene photos, trial transcripts, psychological profiles, police reports, and their permission to contact the criminals and their parents. Cassavetes even took his actors to meet their counterparts, driving Justin Timberlake to a maximum security prison to get the vibe of the actual Frankie, and introducing Sharon Stone to Nicholas Markowitz’s mother, a broken woman who attempted suicide a dozen times in the years after her son's death.

Alpha Dog, pronounced Cassavetes, was “95 percent accurate.” Which was part of why it got buried, thanks to Jesse James Hollywood’s arrest just weeks after the film wrapped. Cassavetes hastily wrote a new ending to the movie, but his problems were just beginning. Hollywood’s lawyers insisted Alpha Dog would prevent their client from getting a fair trial, and used the threat of a mistrial to force Zonen off the case. “I don't know what Zonen was thinking, handing over the files,” gloated Hollywood’s defense team. “It was stupid.”

The publicity, and the delays, dragged out the pain for Markowitz’s family, especially when they heard Cassavetes had paid Hollywood’s father an, er, consulting fee. “Where is the justice in that?” asked the victim's brother. “This just goes on and on, and I’m spending my whole life in a courtroom.”

The film, too, was pushed back a year from its Sundance premiere. Despite casting a visionary young ensemble—Alpha Dog was my own introduction to Yelchin, Ben Foster, Olivia Wilde, Amanda Seyfried, Amber Heard, and the realization that Timberlake, that kid from N*SYNC, could actually act—no one noticed when it slid into theaters in January of 2007. It wasn’t just the bad press. It was that audiences couldn’t get past that Cassavetes’ last film was The Notebook. No way could the guy behind the biggest romantic weepy of a generation make something raw and cool.

But he had. Alpha Dog is a stunning movie about machismo and fate, two tag-team traits that destroy lives. Think Oedipus convincing himself he can outwit the oracle of Delphi. But Sophocles’ Oedipus telegraphs its intentions, elbowing the audience to see the end at the beginning. Greeks sitting down in 405 BC knew they were watching a tale that came full circle. Every step Oedipus takes away from his patricidal destiny just moves him closer to it.

If you map Alpha Dog’s script, instead of a loop, it looks like a horizontal line that plummets off a cliff. For most of its running time, Alpha Dog could pass for a coming-of-age flick where a sheltered kid with an over-protective mom (Sharon Stone) taps into his own self-confidence, right up until the scene where he tumbles into his own grave. Audiences who’d missed the news articles about the case weren’t clued into the climax. Cassavetes doesn’t offer any hints or flash-forwards, not even an ominous “based-on-a-true-story.” (The film might have been more successful if he had.) Instead, he lulls you into joining the kegger, watching Zach crack open beer after beer as though he expects to live forever. “There’s a movie sensibility that the film doesn’t conform to,” said Cassavetes. “You don’t watch this film. You endure it.”

As Zach, his eyes red-rimmed from bong rips, not tears, is shuttled between party dens and wealthy homes, he’s given several chances to escape. He’s even revealed to be a Tae Kwan Do blackbelt who can jokingly flip his captor-buddy Frankie (Justin Timberlake) into a bathtub. But Zach stays put—he doesn’t want to get his big brother Jake (Ben Foster) in more trouble, not realizing that Johnny is too busy making nervous phone calls to his lawyer and his aggro father Sonny (Bruce Willis) to get around to asking Jake for the $1200 in ransom money.

Zach’s death is disorienting, almost as if Psycho's Marion Crane got murdered in the second-to-last reel. In a minivan en route to his execution, he innocently tells Frankie he wants learn to play guitar. “It bugs me that I don’t know how to do anything,” he sighs. Meanwhile Johnny assures his dad that there’s no need to call off the killing. “These guys are such fuck-ups, nothing's gonna happen,” he shrugs, a rare example of cross-cutting that defuses tension in order to make the shock of the gunfire even worse. Up until the last second—even after Frankie binds him with duct tape—a sobbing Zach still can’t believe Frankie would hurt him, and honestly, Frankie can’t believe it himself. And Yelchin’s own early death makes you ache for him to get a happy ending, which Cassavetes dangles just out of reach.

This is how evil happens, says Cassavetes. Masterminds are rare. Instead, people like Frankie can be basically good, but can also be panicky and passive and selfish. Shoving Zach in Johnny’s van was an idiotic impulse by upper middle-class kids, who flipped out when they realized the snatching could get them a lifetime sentence. There’s no honor or glory in the violence. Johnny, the cowardly ringleader, talks tough, but orders his most craven friend, Elvis (Shawn Hatosy), to pull the trigger while he and his girlfriend Angela (Olivia Wilde) get drunk on margaritas. And after the murder, one side effect is that Johnny can’t get an erection. When Angela tries to get Johnny in the mood in their hideout motel, the walls close in on him, suffocating the mood.

Away from his boys, Johnny is weak. Surrounded by them, he's the king. Alpha Dog sets up a culture of animalistic dominance. Johnny’s rental house is basically a primate cage at the zoo, only decorated with weight benches and Scarface posters. All of Johnny’s boys jockey to be his favorite and tear each other down in order to bump up their own rank. Kindness is weakness. When a fellow dealer with the ridiculous nickname Bobby 911 cruises by to negotiate a sale, he snarls at a guy who vouches for him: “You don’t need to tell him I’m good for it, man!”

Elvis, the future shooter, is the lowest member of the pack. He can’t ease into the group without Johnny ordering him to go pick up his pit-bull's poop in the backyard. Why do they pick on Elvis? He owes Johnny a bit of money, but the source of the scorn is simply group think. No one wants to be nice to the outcast, and Elvis is just too sincere to be taken seriously. When Elvis offers to get Johnny a beer, the guys tease him for being in love with Johnny. When he says sure, he does care about Johnny, they twist words into a gay panic joke. Elvis can’t win—they won’t let him—so he literally kills to prove his worth, and winds up sentenced to death row, where the real boy, just 21 at the time of the shooting, remains today. Another life wasted.

Cassavetes humanizes the killers because he wants us to understand how their micro decisions add up to murder. Not just the gunmen. Everyone’s a little to blame. The kids who got drunk with “Stolen Boy” and didn’t call the police. The girls who told Zach that being kidnapped made him sexy. Even Zach’s older step-brother Jake, an addict with a twitchy temper who escalates his war with Johnny to a fatal breaking point. Neither boy will back down over a $1200 debt, and there’s an awful split screen call when Johnny dials Jake intending to bring Zach home, but Jake is so boiling over with anger, his Bugs Bunny voice shrieking with outrage, that Johnny just hangs up the phone.

The opening credits, a montage of the cast’s own old home videos, underline that these were young and happy children—the kind of kids people point to as examples of the suburban American ideal. Over a treacly cover of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” we watch these real life boys being cultured to be brave: riding bikes, falling off dive-boards, running around with toy guns, going through the rituals of young manhood, from bar mitzvahs to karate lessons. Yelchin—recognizably dark-eyed and solemn even as a toddler—grins wearing plastic vampire teeth.

It takes another ten minutes for Yelchin’s character to sneak into the film sideways in a profile shot eating dinner with his parents, played by Sharon Stone and David Thornton. His Zach is barely even visible as brash Jake barges into the scene to beg for money. They say no, Jake stomps out, and Zach finally makes himself seen when he runs after his brother, begging to go anywhere less suffocating. Zach’s mom loves him so much that she watches him sleep. “I’m not fucking eight!” he yelps. He’s 15—practically a man, in his own imagination—and desperate to get away, even if it means mimicking Jake, a Jewish kid who’s so scrambled that he has a Hebrew tattoo on his clavicle and a swastika inked on his back. Jake starts to say that he wishes his own mom cared about him that much, but as soon as he gets vulnerable, he spins the moment into a joke. “Boo for me,” Jake grins, and takes another swig of beer.

“You could say it’s about drugs or guns or disaffected youth, but this whole thing is about parenting,” grunts Bruce Willis’ Sonny Truelove. “It’s about taking care of your children. You take care of yours, I take care of mine.” He’s half-right—his parenting is half to blame. Sonny and his best friend Cosmo (Harry Dean Stanton) taught Johnny to bully his friends. Cosmo, looking haggard and hollow, mocks Johnny for having one girlfriend. “You gotta plow some fucking fields,” he bellows. “Men are not supposed to be monopolous!” Not that “monopolous” is a real word, and not that Cosmo fends off women himself, except in his own big talk.

Cosmo and Sonny’s own posturing gradually emerges as being more dangerous than Johnny’s because it's more integrated into society. They’re the type of creeps who rewrite the rulebook to suit them, and attack journalists who try to tell the truth. When a fictitious documentarian asks Sonny about his son's drug connections, the father shrugs, “Did he sell a little weed? Sure.” But when the interviewer presses him further, Sonny snaps, “I’m a taxpayer and I’m a citizen and you are a jerk-off.”

Cassavetes, of course, understands growing up with a father who left a giant footprint to fill. His father, John Cassavetes, the writer-director of Shadows and Faces and A Woman Under the Influence, was one of the major pioneers of independent cinema. He died when Nick was 30, before his son attempted to take up his legacy. “We never really talked film theory,” said Cassavetes. “My experience with my dad was more along the lines of how to be a man, how to be yourself, how to free yourself from what society tells you to do, how to release yourself as an artist.”

It makes sense that Cassavetes would make his own ambitious, and maddeningly singular film. And perhaps it even makes sense to him that fate has yet to give him the reward he’s earned. Alpha Dog deserves to be acknowledged as one of the most incisive examinations of machismo and the banality of evil. But like his fumbling criminals, he knows he’s not really in charge of his life. Admitted Cassavetes, “I'm not smart enough to really have a master plan for my career.”

#alpha dog#alpha dog movie#nick cassavetes#john cassavetes#justin timberlake#emile hirsch#ben foster#amanda seyfried#olivia wilde#Nicholas Markowitz#Bruce Willis#Harry Dean Stanton#Oscilloscope Laboratories#O-Scope#musings#film writing

11 notes

·

View notes